1. Introduction

Xiud Yax Lus Qim (

Yalu wang 亞魯王, literally “Ode to the King Yalu”) is a type of oral performance and ritual practice associated with traditional Miao (Hmong) funerals and festivals in southern China. In approximately 20,000 lines, this story narrates the creation of the world and the history of Miao ancestors, centering on the life trajectory of the eighteenth king, Yalu—his success, defeat, exodus, and finally leading a Miao renaissance.

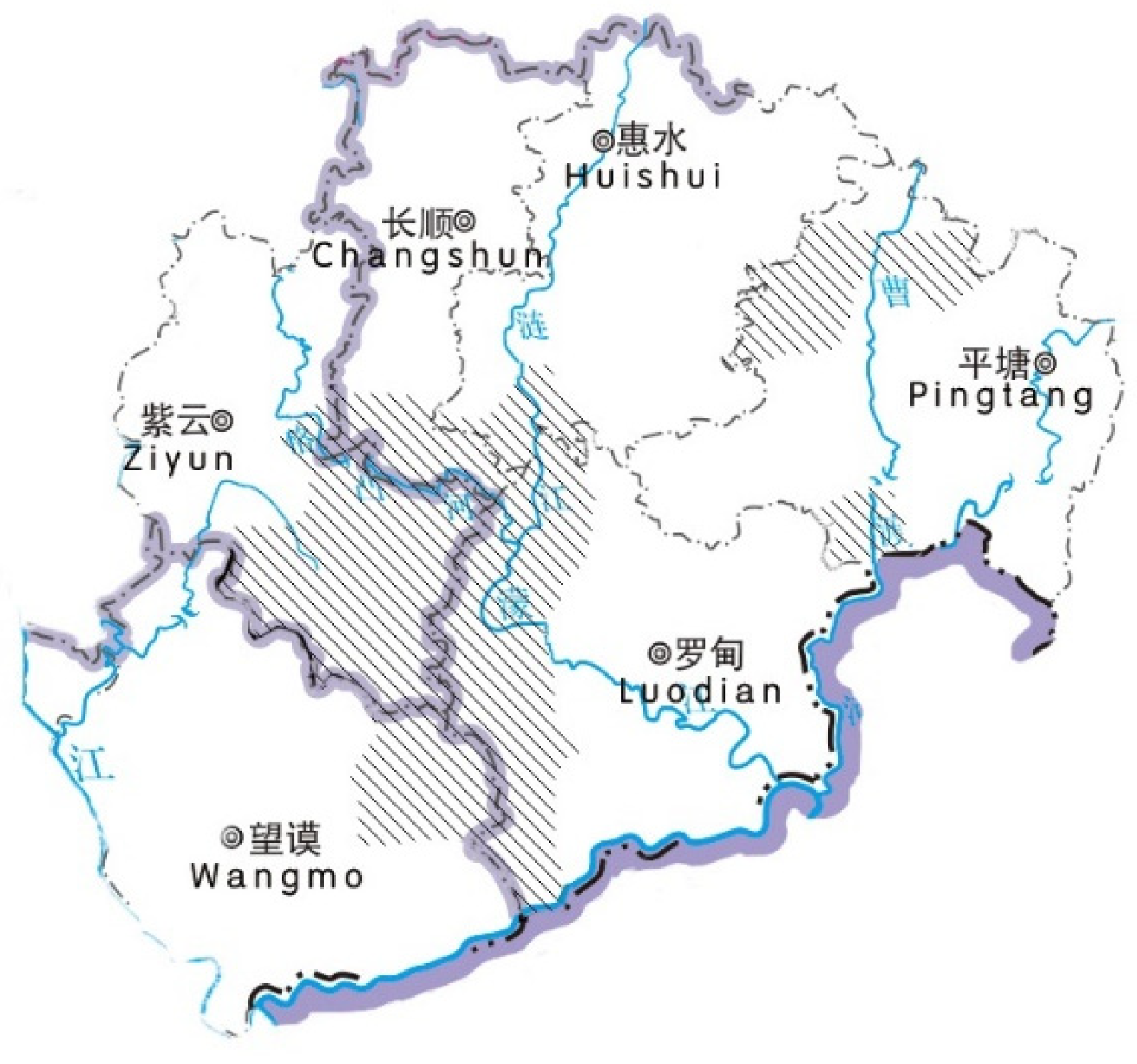

1 Yalu wang is circulated in numerous subdialect groups of the Miao ethnic group, but in most cases it appears as scattered fragments and none are as well preserved as that performed by the Mashan subdialect group. The Mashan area is centered in the city of Anshun, Ziyun county in Guizhou province, and also includes parts of Wangmo, Changshun, Luodian, Huishui, and Pingtang counties (See

Figure 1). The better preservation of

Yalu wang in this area can be attributed to its geographical location in a typical karst topography, which for centuries has left its people in a relatively isolated state (

Tang 2010, p. 89). As cultural contacts with the outside world have historically been extremely limited, many traditional customs, including the oral performance of

Yalu wang and its related ritual practices, are well preserved and are still practiced in a more authentic way.

Official discourses on

Yalu wang first emerged in 2009, soon after it was “discovered” by Yu Weiren 余未人 (b. 1942), the then deputy chair of the Chinese Folk Literature and Art Association (CFLAA), through ethnographic fieldwork in southwestern Guizhou. Following the efforts by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cadres to collect folkloric literature that was launched in Yan’an in the 1940s, and extensively promoted after the foundation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, earlier scholars of

Yalu wang quickly defined the text as a “heroic epic” (

yingxiong shishi 英雄史詩) dating back to 2033–1562

bce. They made parallels with other well-known ethnic epics, such as those associated with the Tibetan cultural hero King Gesar, the

Jangar story of the Mongols, and

Manas of Kyrgyz ethnic groups (

Yalu wang, pp. I–188).

2 Later, Chao Gejin 朝戈金 (

Chao 2012) redefined

Yalu wang as a “composite epic” (

fuhe shishi 複合史詩) since it combines “the characteristics of the three sub-types of epics—heroic epic, creation epic, and migration epic—that circulate in China”. Chao’s argument broadens the definitional aspects of

Yalu wang, but is still confined to the specific field of the epic.

It is salient to argue that the official discourses that define

Yalu wang as an epic (in any form) obviously suggest a type of bias from a literary perspective. With more scholars in other disciplinary fields showing an interest in

Yalu wang, its ritual aspects have more recently begun to draw greater scholarly focus. Yang Liu 楊柳 (

Yang 2016, p. 147), for example, points out that

Yalu wang is commonly used for the ritual practice of

jangz ghad (

kailu 開路, literally “paving the way”) at traditional Miao funerals. In the same vein, Xu Xinjian 徐新建 (

Xu 2014, p. 81) argues that

Yalu wang is not limited to a “heroic epic” but is a “combination of oral and ritual performances”. As a type of ritual practice,

Yalu wang uses oral performance as the vehicle for the Miao sorcery belief in ancestral spirits. Because

Yalu wang is a ritualized performance at Miao funerals, some scholars take

Yalu wang to be a cultural phenomenon that conveys the cognitive aspects of the ethnic group, and refer to the entire ritual practice of

Yalu wang as “Yalu culture” (

Tang 2012, p. 49;

Zhang and Peng 2013, p. 83).

Drawing on the theoretical framework of E.E. Evans-Pritchard, Clyde Kluckhohn, and John Middleton, Zhao Xiaohuan 趙曉寰 (

Zhao 2013, pp. 134–35) sheds light on three complementary patterns in the study of

wugu sorcery (or

wu-shamanism)—loosely rendered as “black magic”—in China: (1) The explanatory, which uses witchcraft to account for misfortunes; (2) The functionalist, which resorts to witchcraft as a means to release unbearable emotions and as a form of social control; (3) The structural, which is concerned with how witchcraft reflects tensions between different social groups and how it is related to the overall social structure. Confirming that

Yalu wang is central to the ritual acts embedded in the sorcery beliefs of the Miao, the discussion here examines it within the context of funerals. It takes as a starting point Jack Goody’s denial of Durkheim’s well-known claim of the “dichotomy of the universe into the sacred and the profane” (

Goody 2010, p. 16), where Goody goes on to define ritual as “a category of standardized behaviour (custom)” (ibid., p. 36). Understood as a manifestation of Goody’s category of custom,

Yalu wang can be said to be “the sum-total of certain rules and cultural achievements, [it] embraces … both Profane and Sacred” (

Malinowski 1948a, p. 41). Based on the embrace of the sacred

and the profane, we observe in

Yalu wang at least two layers of Miao philosophy. First, the ritual acts of

Yalu wang are built on the Miao belief in

wugu sorcery, which, as

Goody (

2010, p. 36) suggests in a different context, is a type of irrational or nonrational behavior used to handle the affairs after death. Second, it echoes what Richard

Schechner (

1993, p. 4) refers to as “the efficacy of ritual acts”, which, in our case, is achieved by the oral performance of

Yalu wang. In terms of ritual, then, the performance of

Yalu wang fulfils its functions on the unity and identity of the ethnic group (ibid., p. 20).

Within the terms of Zhao’s threefold framework, the analysis in

Section 2 elaborates on the content of

Yalu wang and the role of

dongb langf (

donglang 東郎, chanters of

Yalu wang), disclosing their function as the agents bridging the mourners and Miao ancestors at funerals.

Section 3 deepens the examination of the cultural connotations behind

Yalu wang, discussing how the Miao belief in sorcery functions to frame a common history and collective memory that help unite the community and maintain Miao identity in Mashan.

Section 4 looks at how this form has dealt with a more intrusive state presence over the past decade, as

Yalu wang is increasingly and inevitably involved in tensions that have emerged between the local ethnic community, the cultural elite, and state authorities. Bereft of localized features as a manifestation of ethnic knowledge,

Yalu wang has become a state-sanctioned form of “cultural heritage” and a touristic spectacle. The state’s endorsement certainly secures resources for its protection and promotion, and yet the engagement with state power and local government also means a certain kind of disfranchising of

Yalu wang, a situation that leads to a new and pressing need to retain its traditional forms and cultural connotations in the face of dynamic processes of modernization that carry within them both secularization and urbanization.

The data used in this article come from a research trip to Ziyun, Guizhou, in 2021 and fieldwork reports by other scholars, including observations on Miao funerals and interviews with

dongb langf (

Yu 2011;

Cao et al. 2012). For convenience, the texts of

Yalu wang cited here are taken from an edition titled

Xiud Yax Lus Qim, collected by the CFLAA and published by the Zhonghua Book Company (

CFLAA 2011).

3 Using this version for reference does not imply that it can be considered a standardized or definitive form of the text. In fact, there is no single authoritative text; since

Yalu wang is transmitted orally, the chanting of which is relatively flexible as long as it follows a “main narrative”. Within this framework, not only do different individuals have the freedom to alter details, the same

dongb langf can also include ad lib or improvised elements to vary his performances.

2. Yalu Wang and Dongb Langf at Funeral Scenes

Chronologically narrated, the oral performance of

Yalu wang consists of three major topics—

Xiud yangb luf chef (

genyuan 根源, ancestral origins),

Xiud yangb luf qif (

shengping 生平, life stories), and

Langb bangb suob (

puxi 譜系, the offspring) of Yalu, and finally the chanting comes to the family lineage of the deceased. It can be further subdivided into 11 major parts (

CFLAA 2011;

Cai 2019, p. 40):

4Part 1. Lines 1–1176: Creation of the world by ancestral immortals;

Part 2. Lines 1177–1344: Childhood stories of Yalu;

Part 3. Lines 1345–2870: Battle of Naf Njinb and Pel Jinb. Yalu defeats King Lus Wox, former subordinate of Yalu’s father Haed Xix Wus, seizing his land Naf Njinb and Pel Jinb;

Part 4. Lines 2871–4020: Battle of the Dragon’s Heart. Yalu kills a dragon and obtains its heart. His elder brothers, Saem Yangd and Saem Nblam, are jealous and launch a war. At first, they are defeated by Yalu, but later they use Yalu’s consorts, Bob Nim Sangd and Bob Nim Luf, to seize the dragon’s heart. Without the dragon’s heart, Yalu is defeated and driven away from his territory;

Part 5. Lines 4021–5174: Battle of Salt Wells. Yalu flees and leads his followers to Blak Jongt Yind and finds salt wells there. Saem Yangd and Saem Nblam feel jealous and launch another war. Yalu has to lead his followers across the river to find new places to settle;

Part 6. Lines 5175–8086: Exodus. Yalu leads his followers to flee across 30 places, and finally takes refuge at Heid Buf Dok’s kingdom;

Part 7. Lines 8087–9254: Taking Heid Buf Dok’s kingdom by strategy. Yalu and Heid Buf Dok have a duel of wits for dominance over the kingdom. Yalu defeats Heid Buf Dok, drives him off, and takes over his land;

Part 8. Lines 9255–10,819: Reconstructing the new kingdom. Yalu leads his followers to construct his new territory, creates the sun and the moon, and orders his 12 sons to conquer 12 lost places so that these places would inherit the Yalu family lineage;

Part 9. Children of Yalu;

Part 10. Grandchildren of Yalu;

Part 11. Family lineage of the deceased.

Due to successive defeats and the forced exodus of Yalu and his clansmen, the oral performance of

Yalu wang is full of melancholic and grief-stricken motifs, intended deliberately to agitate the collective and affective memory of its audiences. For instance, after the defeat at the Battle of the Dragon’s Heart, the text is replete with images of suffering and resilience (

CFLAA 2011, lines 3977–3984):

Yax Lus jex meinl hah doud (Yalu rides on horseback)

Yax Lus zod kom hah hlongb (Yalu wears black iron footwear)

Yax Lus deib buf dongb nyid lid luok nid lid luok (Yalu’s children cry, boo-hoo boo-hoo)

Yax Lus deib buf waf nyid lid luf nid lid luf (Yalu’s babies cry, waah-waah waah-waah)

Yax Lus njengs soab angt fub lwf (Yalu burns down his homeland, taking field rations along the way)

Yax Lus njengs rongl angt xongm lwf (Yalu breaks apart his kingdom, taking glutinous rice on a long journey)

Yax Lus jongx buf lwf hud heih (Taking his sorrowful clansmen, Yalu sets out on a long road)

Yax Lus jongx buf lwf heid hul (Taking his heartbroken followers, Yalu sets out on a long journey)

His two consorts, Box Nim Sangd and Box Nim Luf, who are cheated by Saem Yangd and Saem Nblam, and whose actions lead to Yalu’s defeat, voluntarily bring up the rear in order to pay witness to their transgressions (

CFLAA 2011, lines 4003–4006):

Box Nim Sangd deib ntox lah meik rum lah qengl (Box Nim Sangd’s blade becomes blunt and she is tired)

Box Nim Luf deib mud lah lod rum lah qengl (Box Nim Luf’s spear is broken and she is exhausted)

Box Nim Sand lah hol zad pwl nyod (Box Nim Sangd falls in a pool of blood)

Box Nim Luf lah hol zad pwl songx (Box Nim Luf falls on a pile of bones)

The circular, repetitive structure of these lyrics generates a sense of deep sorrow, which is further enhanced by the mournful melody of the chanting. Generally, the melody of Yalu wang simply consists of the notes mi, la, and mi2, and each phrase ends with la, either as half notes or crotchets. This conforms to the yu mode (yu diaoshi 羽調式) in the gongche notation (gongche pu 工尺譜) method of traditional Chinese music that uses characters to represent notes. The tonic of the yu mode melody, la, creates a minor mode or scale which is often used to convey sentimental and sorrowful emotions in Chinese music—for instance, in The Butterfly Lovers (Liang Zhu 梁祝), The Moon over a Fountain (Erquan yingyue 二泉映月), and Autumn Moon over Han Palace (Hangong qiuyue 漢宮秋月). The solemn timbre of the drum and lusheng 蘆笙 (a bamboo wind instrument with multiple pipes fitted with free reeds), two typical instruments used for Miao ceremonies and festivals to mediate between the ritual professionals and ancestral spirits, also adds to the mournful emotions of the chanting.

When a Miao dies, their family members fire rifles into the air as a way of signaling their mourning, and then deliver messages to relatives of the same clan. One day before the scheduled date of the funeral, at least 20 to 30, over 100 at most, relatives come to pay respects to the deceased and offer financial support to the bereaved, before listening to the chanting of

Yalu wang at the wake (

Tang 2010, pp. 92–94;

Tang 2012, p. 49). These funerary rituals are not only confined to China. In the Hmong community in the United States, for example, what is referred to as a “traditional full-service funeral” is still partly preserved (

Xiong et al. 2020, pp. 2–3, 7–8).

5 While the details of a Miao funeral may vary according to the cause of death and economic status of the deceased,

Yalu wang is the constant core that is chanted in turn by a group of four to eight

dongb langf at the

jangz ghad ritual, which often lasts from the sunset of the funeral ceremony to the following dawn when relatives carry the coffin onto the mountain for burial. The funeral scene suggests

dongb langf’s identity as a type of ritual professional, whose

mana, or communicable supernatural power, is not an endowment, but comes from “reference to ancestors and culture heroes” (

Malinowski 1948a, p. 55)—in our case, the ability to chant the story of Yalu. Among their number are “big

dongb langf” and “little

dongb langf”, categorized as such by the amount of

Yalu wang they have learned. An extremely experienced big

dongb langf, who is able to chant the full

Yalu wang, is a necessity for funerals, and is for this reason often considered to be the elder in local society (

Yu 2014, p. 304).

Another type of shaman-like ritual professional, other than

dongb langf, is

bot muf (

baomu 寶目). Only able to chant fragments of

Yalu wang (

Yu 2014, p. 303), they primarily use the words as curses in exorcising or divining witchcraft (

Yang 2015, p. 77;

Tang 2012, p. 48). The identities of

dongb langf and

bot muf sometimes overlap:

dongb langf can perform

bot muf’s exorcising and divining roles, but

bot muf cannot preside over funeral rituals in place of

dongb langf. Further,

dongb langf commonly receive no payment for their performance at funerals, and are only given “half or one kilo of meat, a few kilos of rice, and some glutinous rice” (

Xu 2011b, p. 270) as a present; meanwhile,

bot muf often receive payment for exorcising or divining witchcraft. Currently, however, the host family also reimburses

dongb langf’s work in the form of a cash renumeration. Around 2010, the rate of each

dongb langf in Zongdi was 120 CNY (

Tang 2012, p. 55).

6 3. Cultural Connotations behind the Performance of Yalu wang

As shown above, while Yalu wang is defined by folkloric scholars as a heroic epic, this fails to make sense of its central presence at traditional Miao funerals. The Miao vernacular refers to the performance of Yalu wang as “angt Yax Lus” (zuo Yalu 做亞魯, literally “doing Yalu”). This cultural context means that Yalu wang is not limited to an oral form of folkloric literature. An equally, if not more, important aspect is that the oral performance of Yalu wang has to be understood as an entire ritual practice manifesting local knowledge. What, then, is the function of Yalu wang, and in what way is this function realized from the emic point of view?

Yalu wang contains two related cultural connotations which are located at different layers of Miao cognition. Drawing on Erving

Goffman’s (

1959, pp. 106–40) theory of interaction ritual, discourses on the cultural function of

Yalu wang often stand out on the “front stage”, while

wugu sorcery, as the schemata of Miao belief, hides in the “back stage”. As Mary

Douglas (

2001, p. 65) puts it, “Ritual focusses attention by framing, it enlivens the memory”, while Bronislaw

Malinowski (

1948a, p. 64) suggests that ritual “unchain[s] the powers of the past and cast[s] them into the present”. The mortuary routine performed by

dongb langf creates a liminality that juxtaposes the existence of Yalu (the past) and mourners (the present). Just like Confucian rites that draw on emotive criteria to influence reality (

Kertzer 1988, pp. 13–14), the oral performance of

dongb langf forms and reinforces a shared cultural memory at the funeral scene, on the basis of the Miao’s common identity as Yalu’s offspring. Therefore, the history of Yalu is never a dead one. On the contrary, it represents the Miao’s cognition of the external world and forms an ethnic spirit of the group which is, in

Malinowski’s (

1948b, pp. 102–3) designation, “a statement of a bigger reality still partially alive”, and which “rule[s] the social life”.

In this way,

Yalu wang interweaves a “commonwealth” in the Miao ethnic group by “keeping up the memory of its kinship by means of common ceremonies in common places of worship” (

Tönnies 2001, p. 240). How, then, does

Yalu wang successfully convey and sustain this collective memory of the group? Key to this function are the interactions between

dongb langf and mourners based on the oral performance in funerary services as a means of ritualizing memory and kinship. By means of specific and repeated oral performances of

Yalu wang at funeral scenes, this ritual practice is what Paul

Connerton (

1989, p. 14ff.) refers to as a form of “historical reconstruction”, a mnemonic means of performativity that serves to confirm and reinforce the Miao’s collective memory of what is believed to have taken place in history. In this sense, the reminiscent reiteration of Yalu as a deified ancestor and cultural hero at funeral scenes unites the Miao community as an ethnic group and maintains this identity by interweaving emotional interaction and cultural consensus among all the individuals as Yalu’s offspring. This emotive agitation is preeminently important for the legitimacy of an ethnic group or cultural community that may be being hollowed out or threatened by decline. As a representation of Miao ethnic culture,

Yalu wang, as an oral textual artifact, is likely to have become a condensed manifestation of that culture. This caters to the necessity to articulate the Miao’s “otherness” in terms of both geographical and geopolitical issues, as a means to maintain their distinctiveness since the time they dwelled in the barren lands of Mashan during the Ming and Qing eras.

“Public

mise en scène” or “collectiveness of performance” are central to the ritual of

Yalu wang (

Malinowski 1948a, pp. 48–49). In funeral scenes,

dongb langf and relatives of the deceased are not in a one-sided “performer–audience” matrix. Drawing on what Erika

Fischer-Lichte (

2008, p. 43) defines as “the transformative power of performance”, all those present at the funeral are emotionally engaged in a “chain reaction”. The Miao funeral is thus a field of performativity, where relatives of the deceased cry out of grief to the oral performance of

dongb langf, who, in return, feel moved and sometimes become tearful due to the mourning of relatives that adds to the solemnity of the ritual practice. Yang Guangwen 楊光文 (b. 1958) and Chen Xinghua 陳興華 (b. 1945) both have experienced crying while chanting due to the influence of relatives, and Chen even exhorts them not to cry, as he would be too sorrowful to perform the ritual (

Cao et al. 2012, p. 399;

Tang and Ma 2015, p. 72). Therefore, the mutual affect of all parties in the performance plays a central role to the advent of Yalu in the secular realm, and funeral participation thus reinforces the ties in the clan and the ethnic group.

In particular, the historical construction of

Yalu wang enhances the cohesiveness of the Miao ethnic group in two dimensions. On the one hand, the cult of the heroic ancestor Yalu is bound up with the unity of the ethnic group. Part 6, Yalu’s exodus, delineates the migration of Yalu after he is defeated by his older brothers Saem Yangd and Saem Nblam in the Battle of Salt Wells, and this part is formed from the repetition of one passage (

CFLAA 2011, lines 5175–5178):

Yax Lus jex meinl hah doud (Yalu rides on horseback)

Yax Lus zod kom hah hlongb (Yalu wears black iron footwear)

Yax Lus deib buf dongb nyid lid lok nid lid lok (Yalu’s children cry, boo-hoo boo-hoo)

Yax Lus deib buf waf nyid lid lul nid lid lul (Yalu’s babies cry, waah-waah waah-waah)

Part 6 repeats this formulaic passage 30 times, each consisting of 78–80 lines of lyrics, with only the names of places differing (for example, Had Rongl Raen Nogh, and Had Rongl Raen Lim). It takes up a total of 2911 lines—over a quarter of the entire text. The circular structure of this passage generates a sense of vastness and vicissitude, and as such the shared history of encountering and overcoming adversity and suffering interweaves a type of unity among the Miao as Yalu’s offspring. Furthermore, the cohesiveness is achieved by the clan’s sense of shared history. Part 11 of

Yalu wang, the family lineage of the deceased, is a one-hour element in which a

dongb langf chants the Miao names of the clan ancestors for as many as 30 generations (

Yang 2011, p. 249;

Tang 2012, p. 50;

Yang 2015, p. 77). As a Miao custom, the son inherits the last character of his father’s name as the first character of his own name. In this way,

Yalu wang locates an individual in the blood network of his clan. As the

dongb langf Liang Darong 梁大榮 (b. 1952) claims,

Yalu wang functions to “help his clansmen to find their origins” (

Xu 2011b, p. 263).

In extensive interviews,

dongb langf’s belief in

wugu sorcery frequently comes to the fore. This deviates from the argument advanced by

Malinowski (

1948a, p. 43) of the cultural expectation of funerary rites to maintain “the bond of union between the recently dead and the survivors”, which is “of immense importance for the continuity of culture and for the safe keeping of tradition”. In fact,

Yalu wang is directed precisely at the Miao’s fears and doubts in the face of death. In short, it expresses the hope of salvation and immortality (ibid., p. 42). The oral performance of

Yalu wang is therefore understood as a way that

dongb langf exert their communicable supernatural power to direct the deceased to take a journey back to their lost home, as is well reflected in the name of the ritual

jangz ghad, which means “paving the way”. Therefore, before the funeral takes place, relatives of the deceased must prepare “straw shoes, food and drink, bow and arrows, and a rattan helmet” (

Ding 2014, p. 25), which are obviously necessities for a voyager. These can only be sent to the deceased via

dongb langf’s divine power as the agents between the Miao ancestors and the living.

Dongb langf often believe that their supernatural power comes from enacting

Yalu wang. While there is no shamanic trance for the possession of Yalu’s spirit,

dongb langf temporarily assume the identity of Yalu during the

jangz ghad ritual, where they must wear formal blue clothing and a broad-brimmed straw hat to stand in front of the coffin, while holding a long saber. This costume represents the historic attire of Yalu during war campaigns—the formal dress imitates his coat of armor, and the straw hat represents his helmet (

Xu 2011a, p. 143;

Yang 2014, p. 245). In Miao terms, death is either referred to as

lwf bjied (

huijia 回家, literally “returning to the homeland”) or

jinb xiangb (

jinxiang 晉相, literally “assuming the position of prime minister”) (

Ma 2014, p. 94). These two terms are somewhat intertextual in that they echo the closing sections of

Yalu wang, where Yalu dispatches his sons to seize their lost home—Naf Njinb, Pel Jinx, Nax Buf, and Mix Gux. As the oral performance goes (

CFLAA 2011, lines 9499–9510):

Yax Lus lul jongx qws juf box nyab hoh (Yalu leads his 70 spouses)

Yax Lus lul jongx qws juf box nyab lud (Yalu leads his 70 consorts)

Jongx wes lwf paed nongx (Leading them to burn millet)

Jongx wes lwf paed nbaex (Leading them to burn bran)

Jongx wes lwf paed qws bat nboh njux (Leading them to burn 700

nboh njux)

7 Jongx wes lwf paed qws juf meid dwd (Leading them to burn 70 straw shoes)

Yax Lus blaeb mud qws bat lwf qws nongh diah (Yalu throws 700 spears in the direction where the sun rises)

Yax Lus blaeb neind qws juf lwf qws nongh mos (Yalu shoots 70 arrows in the direction where the sun sets)

Yax Lus buf pef qws juf nblah nzal rangx lwf qws nongh diah (Soldiers of Yalu beat bronze drums 70 times in the direction where the sun rises)

Ndangd ndongx ndangd daeb ndangd dwf hlah (Shaking Heaven and Earth, taratatat, taratatat)

Yax Lus jangk plod guf baeb rah gongb dwf hlwb lwf qws nongh mos (Generals of Yalu blow white horns in the direction where the sun sets)

Ndangd ndongx ndangd nzwl ndangd dwf wom (Shaking Heaven and Earth, tarantara, tarantara)

Burning these items is similar to offering sacrifices at funerals, while beating drums and blowing horns are similar to playing solemn funeral music for fallen soldiers. Therefore, in the context of Yalu wang, funerals and campaigns are one and the same. Each funeral restores the scene of a campaign where dongb langf, now in the role of Yalu, promote the deceased as the prime minister and order them to return to their ancestral wonderland.

While most

dongb langf’s front stage narratives suggest that their costume is an imitation of Yalu, to highlight their function of maintaining Miao identity and uniting the community as an ethnic group, the back stage expressions of some

dongb langf present a powerful affirmation of the belief in witchcraft during funeral rites. According to Tang Na’s 唐娜 (

Tang 2012, p. 51) fieldwork report,

dongb langf’s costume is one in which they arm themselves with “instruments that help separate this world from the world after, such as holding a long sabre, and wearing a straw hat (commonly with an ear of rice on top of it) and iron shoes. Before chanting

Yalu wang, the

dongb langf flourishes the sabre around himself as a means to avoid following the deceased to the world after”. Another case is the iron shoes.

Dongb langf often wear them back to front, and this connotes that they can come “back” afterwards.

8 Chen Xinghua has said that most

dongb langf are afraid to perform the closing session of a

jangz ghad ritual where the deceased is sent off on a journey, as they believe if not properly maneuvered the ritual will lead the performer to madness. To separate themselves from the spirit,

dongb langf must declare a departure from the deceased, returning to the world of the living from the liminal space of

jangz ghad:

I am getting farther away from you. You can hear me but can’t see me. I have to tell you this across mountains and rivers: now you have to go to the place you are bound for, but I can’t go any farther. Your shoes are made of cloth and straw and can lead to all the places, but mine are made of iron so I can’t cross the river.

Some

dongb langf’s narratives of their costumes also question the validity of functionalist front stage arguments of “imitation of Yalu’s equipment during war time”, and suggest instead the Miao’s

wugu belief in ancestral spirits. Drawing on the statements of “old-timers”, the

dongb langf Wei Zhengrong 韋正榮 (b. 1952) declared that “

dongb langf did not wear a sabre at

jangz ghad ritual”. The reason is that:

once, a dongb langf was chanting Yalu wang while the watchmen were slumbering. As he chanted on, the dead suddenly jumped up and chased him … into the field. He had no place to hide, so had to use straw to cover his head.… As a result, now dongb langf all wear a straw hat. Later, for fear that this might happen again, dongb langf began to wear a sabre to protect themselves.

However, the discrepancy between the varying, or even conflicting, accounts from

dongb langf cannot be simplified to a matter of either correct or incorrect; honest or dishonest. Their narratives reflect different levels of cultural connotation in

Yalu wang: while most

dongb langf suggest that

Yalu wang is a condensed ritual central to the ethnic identity of the Miao, few are aware of the historical construction behind this master narrative at the front stage. As part of the Miao’s perceptions of the external world, elements of

wugu sorcery normally concealed at the back stage may sometimes come to the fore in an unconscious way, hence the “inharmonious voices” that deviate from the master narrative. Furthermore, the narrative of

Yalu wang evolves around a fixed main narrative, and details of the chanting are sustained by some formulaic sentences or passages, just like the improvisation of a

canovaccio theater form, due to the flexibility of oral performance. However, while the

dongb langf Chen Xinghua argues that “[You should] grasp the main body in the first place, and then add content in accordance with the situation” (

Tang and Ma 2015, p. 71), others are keen to stress the stability in their oral performance (

Cao et al. 2012, p. 144). This “duplicity”, where

dongb langf delineate

Yalu wang as “absolutely inalterable and inviolable”, shows their strategy of convincing, the covert reason of which is to maintain the authority of this oral convention and the authenticity of the cultural construction behind it (cf.

Malinowski 1948a, p. 49). This is certainly somewhat a result of

dongb langf’s desire to maintain their mastery as ritual professionals in local communities but also as spiritual agents in Miao culture. However, they are not necessarily aware of the historical construction that is internalized in

Yalu wang as a cultural set.

4. Increased State Presence and the Status of Yalu wang

Resulting from the successive social and political movements after the foundation of the PRC in 1949, an increased state presence has led to the more aggressive engagement of external forces in the ritual practice of Yalu wang. In the process, where Mashan, once a closed area, was incorporated as an integral part of the Chinese nation-state, the traditional cultural apparatus has been progressively disenfranchised by pervasive state power. Not only were the cultural resources that dongb langf once held overshadowed by political power, the cultural connotations of Yalu wang also faced the predicament of appropriation. Specifically, Yalu wang has been denuded of its structural function as a foundational element of cultural memory that had, in the past, secured the identity of the Miao as an ethnic group. It has been engulfed by the transforming sociocultural projects of the state due to the politicization of social life after 1949. From its decline, since the 1950s to its return as “cultural heritage” in the new millennium, Yalu wang has become a dynamic signifier that is constantly narrated and renarrated by the urgent requirements of the state.

As an embodiment of its determination to depart from the maladies of what it perceived as China’s morbid, moribund past, the CCP called for “eliminating all ghosts and spirits in feudal superstition”, including

Yalu wang and Miao funerals. The

dongb langf Yang Guangxiang 楊光祥 (b. 1936) claims that, during the Great Leap Forward in 1958, “the leaders in the [People’s] Commune did not allow us to perform

jangz ghad ritual for the deceased elderly, declaring that leftovers of the old society were not allowed in the new society” (

Li 2011b, pp. 277–78). Later, in 1966, the onset of the Cultural Revolution witnessed the intensification of this practice, and the

jangz ghad ritual was forbidden: “[Any

dongb langf who] violated this was to be denounced in a struggle session (

pidou 批鬥)” (

Tang and Ma 2015, p. 69). For example, Liao Changhua 廖長華 and Liao Yousheng 廖友生 were sent to the city to attend a “learning class” (

xuexi ban 學習班) of Mao Zedong thought and were only allowed to return home six months later (

Gao 2014, p. 371). Tang Na (

Tang 2012, p. 56) describes this tension as “the apex of the conflict between folk belief and state ideology”, in which “

dongb langf were forced to choose between

Yalu wang and Chairman Mao”. However, these two choices were not as straightforwardly exclusive as Tang suggests. In fact, folk belief showed a strong sense of malleability and adaptability in the face of state ideology. Secret practices of traditional funerals were frequently performed. Not only would

dongb langf venture a performance of

Yalu wang, some local party cadres also chose a laissez-faire attitude toward folk belief and considered inspections of ritual practices a mere formality.

The end of the Cultural Revolution did not mean a return to

Yalu wang’s prior status. Quite the contrary, for rather different structural reasons, it underwent a more serious decline after the launching of the reform and opening by Deng Xiaoping 鄧小平 (1904–1997) in 1978. Due to China’s modernizing program, featuring a distinctively Chinese variant of the market economy, the state partially withdrew from people’s private lives, while the vigorous pursuit of profits and personal wealth became a new challenge to folk beliefs in local society. In the cultural domain, the homogenizing tendencies of modernity also threatened to remove all differences, ethnic differences included. Since the mid-1990s, young people have left Mashan to become laborers in Guangdong and Guangxi for better pay. According to the

dongb langf Yang Baoan 楊保安 (b. 1952), “Very few people come to see us chanting [

Yalu wang] now, primarily because there are fewer people in the village. Many young people work outside. Often, at

jangz ghad rituals just a few of us—

dongb langf—accompany the host family at the wake” (

Li 2011a, p. 183).

Before

Yalu wang was “discovered” by Yu Weiren in 2009, it had never been interwoven in a more intricate nexus of wider social forces, which would have accelerated its acculturation. The dubious and one-dimensional discourse that presented

Yalu wang as an ethnically particular historical epic was in fact a projection on the part of the state to renarrate its core meaning. As noted above, at least five decades before Yu Weiren declared her discovery of the “heroic epic”,

jangz ghad performed by

dongb langf at Miao funerals had already been identified by the CCP and “forbidden”, as it was deemed a manifestation of outmoded superstition. The only difference is that, while in the 1950s,

jangz ghad was considered a ritual, the central content of

jangz ghad,

Yalu wang, is now extricated from its integrated ritual practice and is bestowed with a brand-new and more palatable cultural-political label as an “epic” in the corpus of ethnic literature. In 2011, the state added

Yalu wang to the “List of National Intangible Cultural Heritage” (

DMCNICH 2011, I–118). While this approbation secured protection and promotion from the state, this close engagement and indeed oversight of the state turned

Yalu wang into a more secularized emblem of the state’s cultural confidence. As various official discourses suggest, the state has renewed the historical narrative that the Miao ethnic group does indeed possess an epic genealogy, a noted addition to the treasury of world literature. At the same time, however, this officially sanctioned endorsement deliberately disconnects

Yalu wang from its cultural context as a funerary ritual practice that is central to Miao identity formation and maintenance.

This process of silencing is even more evident in the case of the local governments of Ziyun and Anshun, the agencies directly responsible for Yalu wang’s protection and promotion. Their foremost concern is Yalu wang’s value as a tourist attraction and as a means for generic cultural promotion, ultimately with the instrumental aim of securing economic benefits. After 2011, Yalu wang became a cultural trump card of Anshun, and the official account of the Publicity Department of the CCP Ziyun Committee on WeChat is named “Yalu Ziyun”. The form and discourse officially promoting Yalu wang is, in every substantive meaning, a form of disenfranchisement—it was deliberately removed from its traditional context of funerary rites while catering to an outsider audience’s voyeuristic curiosity to peep into the lifestyle of so-called “ethnic minorities” (shaoshu minzu 少數民族).

Taking advantage of the “discovery” of the epic, the Ziyun authorities have been focusing on the construction of the Getu River Scenic Area, hidden in the mountains south of Anshun, as its economic engine and cultural showcase. The strategy of the local government clearly shows a desire to rely on

Yalu wang as a means of tourist advertising. In May 2018, Ziyun launched a 560 million CNY project called “Yalu Wang City” (

Yalu wang cheng 亞魯王城) in Getu, aiming to use

Yalu wang to develop its cultural attraction as a form of “ethnic tourism”. Yalu Wang City is located at the foot of a mountain, and includes a royal court, a sacred city, and a living area. In October 2018, a burlesque performance of

Millennium of Yalu Wang (

Qiannian Yalu wang 千年亞魯王) was presented in Yalu Wang City as a tourist attraction three times a day. One other very obvious, and slightly bizarre, manifestation of this “reinvention of tradition” illustrates the primacy of the pursuit of tourist income. Huang Xiaobao 黃小寶 (b. 1962), a

dongb langf and expert in free climbing, has performed at the 108-meter cliff face in Getu since the 2000s (

Cao et al. 2012, pp. 337–38). Moreover, in October 2010, the local government of Ziyun first created a connection between Getu and

Yalu wang through the “

Yalu Wang cultural tourism festival and Getu River rock climbing challenge”. As the advertisement suggests, “welcome to the hometown of

Yalu wang”, Getu now receives official empowerment as the representation of

Yalu wang.

What should be clear is that these activities in the name of

Yalu wang are merely scattered cultural fragments removed completely from their traditional cultural context of Miao funerals.

Yalu wang is historicized, that is, it is bereft of all its deep-seated functions as a historical construction that maintains a distinctive ethnic identity. In 2011, Ziyun county performed a tailor-made program, “Yalu Wang Crosses the Mountain of the Knife and the Sea of Fire” (

Yalu wang zhi daoshan huohai 亞魯王之刀山火海), at the ninth National Traditional Games of Ethnic Minorities. As its name suggests, performers climbed a bamboo ladder barefoot, with each rung made of blades. Another group of performers walked across a burning iron plate, also barefoot. While presented in the name of

Yalu wang, this performance was not Miao in any shape or form. Technically, the program comes from the Knife-ladder Climbing Festival (

Daoganjie 刀杆節) of the Lisu ethnic group (

DMCNICH 2006, X–27). The

Yalu wang elements were added arbitrarily to the program, which is more of a dazzling acrobatic performance chosen as an emblem for Guizhou in the national pageant.

Even more egregiously, some local performance agencies have distilled the funeral chanting into stage performances which synthetically embrace instrumental music—drum, suona 嗩吶 (double-reeded horn), and lusheng—oral/vocal performance, and choreography. With different forms of programs, various agencies are competing for the cultural resources of Yalu wang. Currently, there are two established programs: one is Millennium of Yalu wang and the other is a “choral theater” production titled Yalu wang, which debuted in December 2018. These two performances show the different perceptions of two groups—Miao scholars and the (Han Chinese) cultural elite—on what elements in Yalu wang can stand in for the Miao ethnic group.

Elements of traditional resources and tourist attractions coexist in Millennium of Yalu wang. Performed on a temporary stage at the central square of Yalu Wang City, this program is directed by Yang Zhengjiang, who is a dongb langf contributor to the 2011 version of Yalu wang, and currently a cultural cadre of Ziyun. The performance area is divided into three major parts: three dongb langf upstage, six percussionists downstage, and several groups of dancers take turns to perform center stage. Starting from a series of queries into “who am I, where am I from, where are my ancestors, and where is my hometown?” the 20-min program evolves around the main narrative of the Yalu wang stories, from the creation of the world to Yalu’s success, love, defeat, exodus, reconstruction, and renaissance of the Miao regime. In each section, dongb langf chant an excerpt from Yalu wang in Miao vernacular, with a narrator summarizing the story in Mandarin Chinese. Generally, this program seizes the cultural context of Yalu wang, following its main narrative to show the Miao ethnic group’s remembrance of their hometown. Moreover, while not clarified, in the second scene, “Ritual”, a screen behind the dongb langf plays a video of a traditional Miao funeral ceremony, which, to some extent, suggests the original funeral scene of Yalu wang. However, this program is more a theatrical performance than a ritual practice, so it adds showbusiness elements to the chanting of Yalu wang. While it resorts to the acrobatics of knife mountain climbing and fire-eating to attract tourists, other performances are choreographed with reference to Miao dances. For instance, in the scene “Exodus”, a performer and a lusheng musician would stand on their heads while performing. This is a fragment absorbed from the Small Flowery Miao (Xiaohua miao 小花苗) ethnic subgroup and their “Little Dance of Migration” (Xiao qianxi wu 小遷徙舞), a dance that also derives from the retreat of Yalu during a battle. Hence, the past is accumulated in the performers’ bodies.

In deep contrast to

Millennium of Yalu wang, the choral theater production

Yalu wang is performed by a chorus of 400 vocalists at Guiyang Grand Theater, after half a decade of collaboration with more than 30 well-known artists. As a project fully funded by the CCP Publicity Department of Guiyang, this choral theater reflects the cultural elite’s desire to dominate the discourse of ethnic culture. This theater piece has hardly any melody derived from the chanting of

Yalu wang. As the music director Xiao Bai 肖白 and the conductor Fang Ling 方玲 declared, the reason is that folk music (the chanting of

Yalu wang) in Ziyun is not representative of the Miao ethnic group, so they used a series of modes and scales distilled from Miao music to create a new melody (

Yue 2019). While they argue that the melody is “undoubtedly Miao”, it is absurd (and arrogant) to think that a reinvention is more Miao than the Miao culture embodied in

Yalu wang. In fact, the vocal performance of this theater piece basically follows the principles of the bel canto lyrical style used in operatic arias and accompanied by an orchestra and chorus. The

yu mode of

gongche solfège that features sentimental and sorrowful emotions is removed, and in its place now is an epic scene recreated via the timbre of bel canto. The panegyric of “the first music theater of the Miao’s epic in China” (ibid.) shows an official endorsement of the cultural elite vying for

Yalu wang’s cultural resources, which are finally and fundamentally turned into a disconnected, disembodied “heroic epic” in official discourses.

This juxtaposition of the practices of various actors clearly shows a tension between an ethnic legacy as an organic form of local knowledge and the reinvented ethnic heritage by the cultural elite. As the title of a report, “What Can Represent the Miao Ethnic Group?” (ibid.) suggests, the cultural elite believe that they are representatives of ethnic cultures. In this sense, if performance agencies only take fragments of music and theater out of the ritual practice of Yalu wang, the cultural elite’s brand-new creation dislodges Yalu wang from an ethnic culture embedded in folk belief and sorcery, relocating it within an acceptable and commercialized framework of state-sanctioned cultural heritage.

5. Conclusions

Originally, Yalu wang was a type of oral performance, a central element of the ritual practices at Miao funeral rites. From an emic point of view, the dongb langf have divine powers to direct the deceased to the lost home of their progenitors. The content of Yalu wang includes Yalu’s role in Miao warfare, their exodus, and the lineage of his offspring. As a cultural artifact, it creates a liminality at funeral scenes that juxtaposes the past and the present, which in turn recreates and reinforces the collective memory through a form of performativity participated in by all. In sum, the Yalu wang funerary rituals serve as a means to maintain ethnic identity and unite the local community. This functionalist framework is built on the Miao’s wugu belief that the interactions between the living and ancestral spirits can be properly mediated and controlled by the witchcraft of dongb langf. These two dimensions speak to two layers of the Miao’s cognition of the external world, and are both confirmed in the front stage and back stage narratives of dongb langf.

After it was officially “discovered” in 2009, Yalu wang has been woven into the nexus of diverse and sometimes contradictory discourses articulated by various forces that vie for its cultural resources. Even the term “Yalu wang” itself is a new cultural construct. While state observation—and prohibition—of the performance of jangz ghad rituals has been a reality since the 1950s, Yu Weiren’s appropriation of the ritual has cleansed it of all elements of sorcery and has redefined it as a straightforward heroic epic. This process is merely one more example of the state-driven epic collection project that has been in train for the past six decades. Yalu wang is therefore endorsed in the official discourse as a gap-filling discovery that has rewritten a historical narrative that previously posited that the Miao have no epic of origins. As we have seen, in 2011, Yalu wang entered the “List of National Intangible Cultural Heritage”, which secured financial support for its protection and promotion at the state level. While the state uses Yalu wang as a demonstration of its own cultural confidence, the local government of Ziyun cherry-picks its cultural elements as a tourist attraction to obtain economic benefits or to present Guizhou’s “ethnic culture” in national pageants. The fact that some (Han Chinese) artists believe their contemporary performance is more Miao than traditional Miao performances is an example of a desire to seize elements from ethnic cultures in order to develop a commercialized creative industry.

While on the surface all these actions are said to preserve, protect, and promote Yalu wang, in fact they threaten to hollow out Yalu wang from its core cultural context, since few if any of these activities and programs directly mention Yalu wang’s function at funeral rites. Either way, the reinvented Yalu wang has lost its meaning in the local community for the Miao, becoming fragments bereft of cultural context. The fate of Yalu wang is representative of the paradoxical status quo of all ethnic cultures in a rapidly globalizing and commodifying China (and we may add elsewhere too). As modernization, urbanization, and secularization ultimately lead to a kind of cultural homogeneity, almost all these ethnic cultural practices, as with Yalu wang, face the plight of erosion, dilution, or even elimination. “Intangible cultural heritage” affords them a means of survival, yet at the cost of being divorced from their cultural contexts. This shift from local knowledge to national/universal culture in fact severs its ties to the ethnic group that gave birth to it.