Secularization, Modernity, and Belief Shaping: Night School and Livelihood Education at the Chinese YMCA in the Early Twentieth Century

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Aims and Methods

4. Result

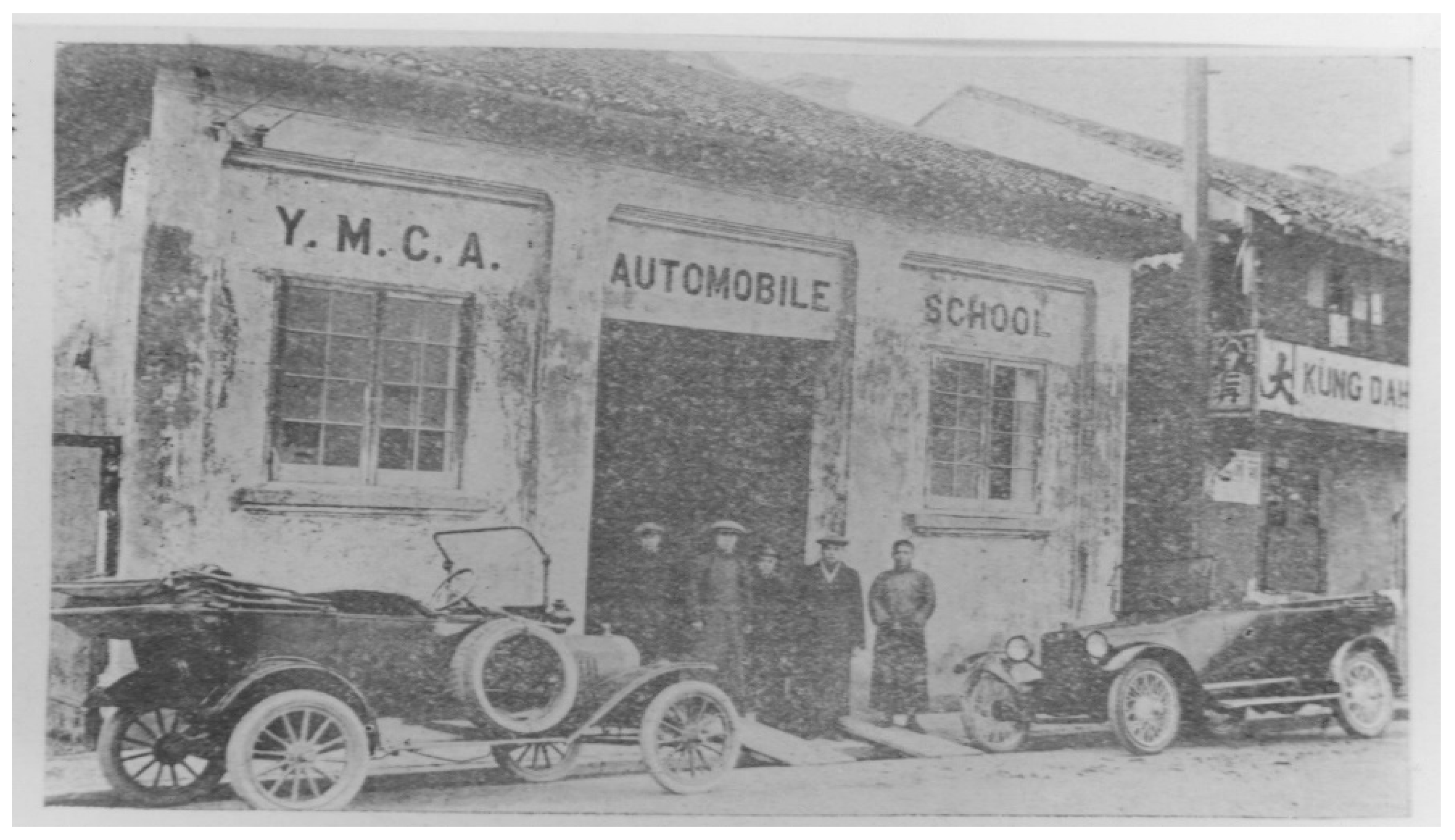

4.1. The Establishment and Purpose of the YMCA Night Schools for Workers

4.2. Main Programs and Mission

4.3. Teaching Achievements of Night Schools

4.3.1. Improved Living Conditions for the Urban Working Class

4.3.2. Nurtured Excellent Representatives

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The original Soochow University (Chinese: 東吳大學) was founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South in Suzhou in 1900. |

| 2 | The China National Democratic Construction Association (CNDCA), sometimes translated as the China Democratic National Construction Association (CDNCA), also known by its Chinese abbreviation Minjian (民建), is one of the eight legally recognized minor political parties in the People’s Republic of China that follow the direction of the Chinese Communist Party and are members of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. It was founded in Chongqing in 1945 by the Vocational Education Society, a former member of the China Democratic League. |

| 3 | The Hanlin Academy was an academic and administrative institution founded in the eighth-century Tang China by Emperor Xuanzong in Chang’an. Membership in the academy was confined to an elite group of scholars who performed secretarial and literary tasks for the court. One of its main duties was to interpret Chinese classics. Shujishi (Chinese: 庶吉士), which means “all good men of virtue”, is a scholastic title from the Ming and Qing dynasties of China. It can be used to denote a group of people who hold this title and individuals who possess the title. |

References

- Annual Report of Chinese Young Men’s Christian Association of Shanghai. 1901. Records of YMCA International Work in China, Kautz Family YMCA Archives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Report of Chinese Young Men’s Christian Association of Shanghai. 1903. Records of YMCA International Work in China, Kautz Family YMCA Archives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1912. Zhongguo Qingnianhui Banye Xuetang Xinhai Jianzhang 中國青年會半夜學堂辛亥簡章 [Articles of YMCA for the Night School]. Shanghai: Shanghai YMCA. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1915. ‘Shangye Xuexiao Banye Xuetang Zhangcheng’ 商業學校半夜學堂章程 [Articles of YMCA for the Business Night School]. Shanghai: Shanghai YMCA Business Night School. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 1924. Gong Kedan 功課單 [Homework Sheet]. Shanghai YMCA News, October 23. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yu Cheng. 2020. God’s Model Citizen: The Citizenship Education Movement of the YMCA and Its Political Legacy. Studies in World Christianity 26: 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, Ryan. 2012. Selling the Mission: The North American YMCA in China 1890–1949. Taiwan: National Central University, Retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11299/140888 (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Burgess, John Stewart. 1928. The Guilds of Peking. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, John Stewart. 1929. Certain Concepts, Methods and Contributions in the Social Science and Social Philosophy of LT Hobhouse. The Chinese Social and Political Science Association 13: 119. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, John Stewart. 1930. The guilds and trade associations of China. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 152: 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Xiao Hua. 2011. Shangdizhinv tazhongmeigui—Lun chengy zhen de wen ue chuangzuo 上帝之女 塔中玫瑰—論程育真的文學創作 [The Rose in the Tower and God’s Daughter—On Cheng Yuzhen’s Literary Creation]. Journal of Ningbo Institute of Education 13: 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Litin 陳立廷. 1927. ‘Qingnianhui zhi jiaoyu diwe’ 青年會之教育地位 [The Status of Youth Education]. Shanghai Qingnian 上海青年 [Shanghai Youth] 26: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Yuzhen 程育真. 1944. ‘Fuqin’ 父親 [Father]. Xiaoshuo Yuebao 小說月報 [Fiction Monthly] 45: 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Yuzhen 程育真. 1949. ‘lvcheng Riji’ [旅程日記]. Zhongmei Zhoubao 中美週報, Sino-American Weekly, February 24. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Xiao Qing. 2006. About Cheng Xiaoqing. In Sherlock in Shanghai: Stories of Crime and Detection by Cheng Xiaoqing. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- China YMCA National Association 中華基督教青年會全國協會編, ed. 1935. Zhonghua Jidujiao Qingnia Hui Wushi Zhounian Jiniance (1885–1935) 中華基督教青年會五十週年紀念冊 (1885–1935) [China YMCA 50th Anniversary Memorandum (1885–1935)]. Shanghai: China YMCA National Association. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Chung Cheuk-Chi. 2019. Politicized Faith: The Transformation of the Discourse” Character, China’s Salvation” of the Chinese YMCA, 1908–1927. Ching Feng 18: 123–47. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Department of Cultural and Historical Data of Shanghai Political Consultative Conference, ed. 1996. 上海市政協文史資料編輯部編 ‘Shanghai de Zongjiao’ 上海的宗教 [Religion in Shanghai]. Shanghai: Xinhua Bookstore. [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds, Charles K. 1919. Modern education in China. The Journal of International Relations 10: 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, John King, Edwin O. Reischauer, and Albert M. Craig. 1973. East Asia: Tradition and Transformation. London: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Shirley S. 1970. Social Reforms in Urban China: The Chinese Y.M.C.A., 1895–1926. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Zhao Guang. 1997. ‘Shixiantongshu de yiwei’ 《時憲通書》的意味 [The meaning of Shixiantongshu]. Dushu 讀書 [Reading] 1997: 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Michael Allen. 2008. The Theological Origins of Modernity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Merle, and Elizabeth J. Perry, eds. 2002. Changing Meanings of Citizenship in Modern China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guangzhou YMCA, ed. 1934. Guangzhou Qingnian. Guangzhou: Guangzhou YMCA. [Google Scholar]

- Guangzhou YMCA, ed. 2019. Annual Report of Guangzhou Y.M.C.A. Beijing: Religious Culture Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford, Charles Wishart. 1979. Rural Reconstruction in China: YC James Yen and the Mass Education Movement. Cambridge: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, Emily. 1996. Christianity, Feminism, and Communism: The Life and Times of Deng Yuzhi. In Christianity in China: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present. Edited by Daniel H. Bays. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 243–62. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Hai Bo. 2013. Zongjiao Feiyingli Zuzhide Shenfenjiangou Yanjiu: Yi Shanghai Jidujiao Qingnianhui Weili 宗教性非盈利組織的身份建構研究 [Research on the Identity Construction of Religious Nonprofit Organizations: A Case Study of the Shanghai YMCA]. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiaohui Zhushujia Xiboshou Xiansheng Xingshu 教會著述家奚伯綬先生行述. [The introduction of the Church publisher Xi Boshou]. 1916. Zhonghua Jidujiaohui Nianjian 中華基督教會年鑒 [Yearbook of the Christian Church of China]. Shanghai: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinkley, Jeffrey C. 2000. Chinese Justice, the Fiction: Law and Literature in Modern China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Lv Jian 林呂建. 2013. Zhejiang Min’guo Renwu Dacidian 浙江民國人物大辭典 [Dictionary of People in the Republic of Zhejiang]. Zhejiang: Zhejiang University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jing Quan, ed. 1999. Zhongguo Kangri Zhanzheng Renwu Dacidian 中國抗日戰爭人物大詞典 [Dictionary of Chinese People in Anti-Japanese War]. Tianjin: Tianjin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peake, Cyrus Henderson. 1970. Nationalism and Education in Modern China. New York: H. Fertig. [Google Scholar]

- Peking YMCA, ed. 1929. Beijing Jidujiao Qingnianhui Yingwen Yexiao Zhangcheng 北京基督教青年會英文夜校章程 [Articles of Association for the English Night School]. Beijing: Peking YMCA. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Elizabeth J. 1993. Shanghai on Strike: The Politics of Chinese Labor. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rawski, Evelyn S. 1979. Education and Popular Literacy in Ch’Ing China. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Xiang, ed. 2013. Zhongguo Zhentan Xiaoshuo Lilun Ziliao 中國偵探小說理論資料 [Theoretical Materials of Chinese Detective Novels]. Beijing: Beijing Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, Hans. 2005. Theology in a Global Context: The Last Two Hundred Years. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner, Larry. 1967. The concept of secularization in empirical research. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 6: 207–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, Jonathan D. 1982. The Gate of Heavenly Peace: The Chinese and Their Revolution, 1895–1980. London: Faber & Faber Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Dong. 2005. China’s Unequal Treaties: Narrating National History. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Zhou. 2010. ‘Chen Sisheng yu Shanghai Minjian’ 陳巳生與上海民建 [Chen Sisheng and the Shanghai Committee of China National Democratic Construction Association]. ‘Shanghai Minjian Lishi Dang’an’上海民建歷史檔案 [Historical Archives of the Shanghai Committee of China National Democratic Construction Association]. Available online: http://www.mjshsw.org.cn/n2967/n2973/n3186/u1ai1818522.html (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Xing, Jun. 1993. Baptized in the Fire of Revolution: The American Social Gospel and the YMCA in China: 1919–1937. Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minnesota, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Zhi Wei. 2010. Jiduhua yu Shisuhuade Zhengzha, 1900–1922: Shanghai Jidujiao Qingnianhui Yanjiu [The Struggle between Christianization and Secularization, 1900–1922: Research on the Shanghai YMCA]. Taipei: National Taiwan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Li Qun. 2019. Sinicization and Professionalization: YMCA and Modern Civilian Education: With the Guangzhou YMCA as an Example. Revista do Instituto Politécnico de Macau 73: 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Shan Jiu. 2019. ‘Chen Si Sheng yu Chen Zhen Zhong’ 陳巳生與陳震中 [Chen Sisheng and Chen Zhengzhong]. Beijing: Chinese Literature and History Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Fu Rong. 2003. Social Gospel and Social Service: A Case Study of Peking YMCA (1909–1949). Doctor’s dissertation, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar]

| Subject | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Room | Instructors | Fees Memb’s | Fees N.Memb’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English, Primer | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 43 | Mr.O.Z,Lee | 6 | 11 | |

| English, I, Reader | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 43 | Mr.O.Z,Lee | 6 | 11 | |

| English, II, Reader | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 44 | Mr.C.Y.Hsu | 6 | 11 | |

| English, III, Reader | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 44 | Mr.C.Y.Hsu | 6 | 11 | |

| English, IV, Reader | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 46 | Mr.A.S.F.Chur | 6 | 11 | |

| English, V, Reader | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 7–9 | 46 | Mr.A.S.F.Chur | 6 | 11 | |

| English, Advanced | 8–9 | 8–9 | 8–9 | 47 | 6 | 11 | ||||

| French | 8–9 | 7–8 | 8–9 | 42 | Mrs.G.A.Fitch | 7 | 12 | |||

| Mandarin | 6–7 | 6–7 | 6–7 | 48 | Mr.C.T.Lieu | 5 | 10 | |||

| Chinese Classics | 6–7 | 6–7 | 6–7 | 6–7 | 42 | Mr.Y.C.Chow | 5 | 10 | ||

| Translation | 7–8 | 7–8 | 42 | Mr.N.Y.Chang | 3 | 8 | ||||

| Book Keeping, I | 7–8 | 7–9 | 42 | Mr.F.Francis | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Book Keeping, II | 8–9 | 7–9 | 41 | Mr.F.Francis | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Book Keeping, III | 8–9 | 7–9 | 42 | Mr.R.W.Waccabe | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Typewriting | 8–9 | 7–8 | 8–9 | 48 | Miss Brooks | 12 | 17 | |||

| Commercial Practice | 8–9 | 7–8 | 8–9 | 48 | Mr.G.B.Fryer | 7 | 12 | |||

| Religion and Ethics | 7:45–8:15 | M.M.Hall | ||||||||

| English Bible | 7–8 | Lecture Hall |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ko, K.-Y. Secularization, Modernity, and Belief Shaping: Night School and Livelihood Education at the Chinese YMCA in the Early Twentieth Century. Religions 2021, 12, 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100897

Yang Y, Liu X, Ko K-Y. Secularization, Modernity, and Belief Shaping: Night School and Livelihood Education at the Chinese YMCA in the Early Twentieth Century. Religions. 2021; 12(10):897. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100897

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yi, Xunqian Liu, and Kuan-Yu Ko. 2021. "Secularization, Modernity, and Belief Shaping: Night School and Livelihood Education at the Chinese YMCA in the Early Twentieth Century" Religions 12, no. 10: 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100897

APA StyleYang, Y., Liu, X., & Ko, K.-Y. (2021). Secularization, Modernity, and Belief Shaping: Night School and Livelihood Education at the Chinese YMCA in the Early Twentieth Century. Religions, 12(10), 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100897