Pedalling Out of Sociocultural Precariousness: Religious Conversions amongst the Hindu Dalits to Christianity in Nepal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Social Theory of Religious Conversion

3. Historical Overview of Christianity in Nepal

4. Materials and Methods

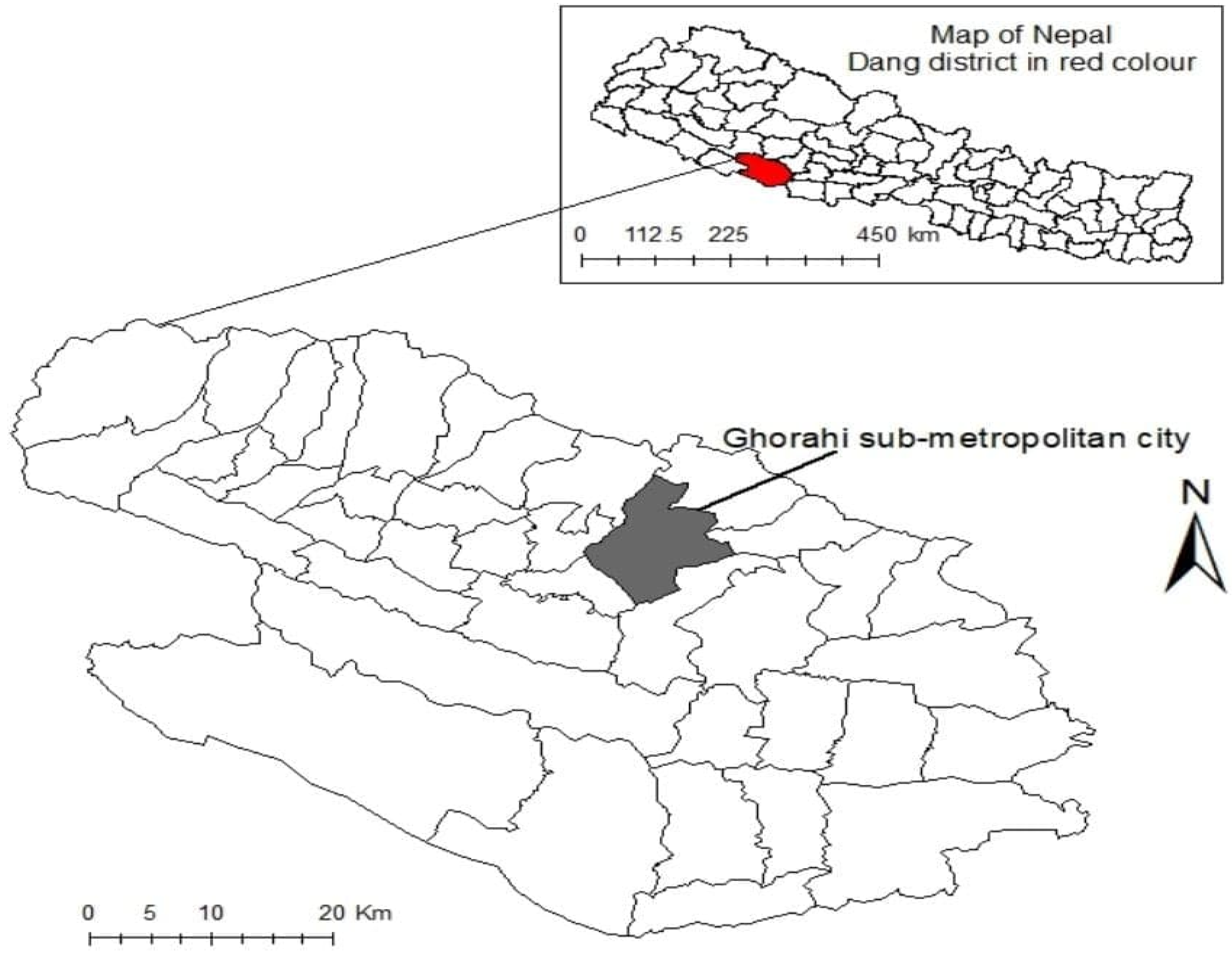

4.1. Study Site

4.2. Research Methods

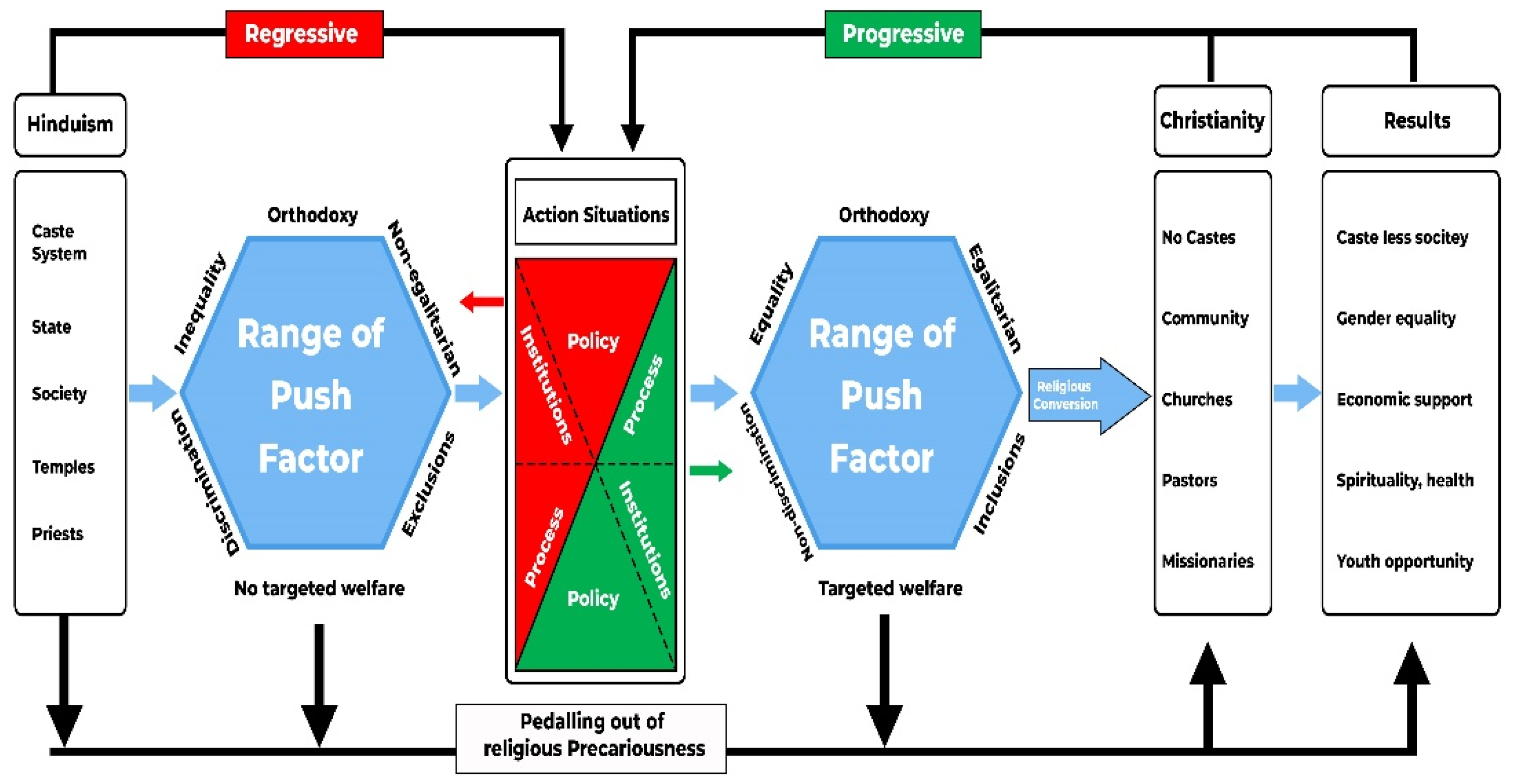

5. Analysis and Discussions

5.1. Overcoming Sociocultural Discrimination

[…Walking to the temple, singing, and dancing together during the ladies festival of Teej has no meaning; we were not allowed to enter inside the temple, we had to worship outside the temple. But once our family converted to Christianity, other fellow Christians do not treat us differently …][Dalit Female, 55 years old]

[… 21 years old Dalit man and his other five friends were brutally murdered and thrown into a swelling river in Rukum District in western Nepal just for falling in love and attempting to marry a girl from higher caste…][Dalit Male, 24 years old]

[…I was trying to buy land from a higher caste Brahmin to open a fresh house (meat shop). Instead of selling his land to me, a local higher caste Brahmin family sold it to another non-Dalit customer despite me offering competitive price because his high caste neighbour did not want me to set up a meat shop in his area as I was a Dalit, but I also had the money, mine was cash too…][Dalit Male, 45 years old]

[…Under Hinduism, Dalits have become like deadweight as caste-based hierarchy constrains opportunity to play an active role in village sociocultural life. Upon conversion, I have become a pastor in the local church;, our youths, girls, and women are also active in the church group. All Christians are children of Jesus Christ, the God. There is no caste amongst the Christians…][Dalit Male, 27 years old]

5.2. Improving Gender Equality

[… In this Hinduism, girls, and women are blamed for family misfortunes, and rights of girls and women are rarely taken seriously. We are considered just the characters to justify the reputation of the Hindu religion….The world has moved on so much, but the Hindu religion has remained the same…][Dalit Female, 35 years old]

[…After getting married, and before conversion from Hindu to Christianity when I came in my husband’s house I had to address everyone respectfully even if they are younger than me, especially male members of my husband’s family…][Dalit Female, 40 years old]

[…We had to stay in cowsheds during menstruation because girls and women have periods because of the sin committed in the previous life. By living in the cowsheds we are cleansing ourselves from the sins. However, when we converted Christianity, there is nothing like that…][Dalit Female, 34 years old]

[“…I feel good and happy with friends in the church in this old age. I used to be scolded, discarded, and thrown out of the house for only giving birth to girls. I feel why I didn’t convert to Christianity a long time back; life is good here in the church…”][Female, 65 years old]

[…When I was a Hindu, I was just a daughter-in-law in the family undertaking household chores. Once we converted to Christianity, I learned to read and write, and my daughter is attending a bible college. I also got a peon job in an office because I learned to read and write, which was possible through the church community; and no more abuse by husband …][Dalit Female, 45 years old]

5.3. Economic and Educational Support

[…Before conversion to Christianity, we had to give so much donation to the Priests, who was the only beneficiary, and the community, did not get any benefit from such donations. Donations and offerings were made to make our dead ancestors happy…][Dalit Male, 36 years old]

[…Whatever funding is raised through donations is used for management of the church. The church committee also used provided loans to do things like celebrating festivals and starting up small businesses. This is such a necessary and useful funding for us…][Dalit Male, 45 years old]

[…We were just Dalits for this Hindu society. Once I converted to Christianity, I developed friendship and family ties with other Christians. Just a few days ago my daughter had a coffee bean stuck in her ear, and one of the churchgoers supported her treatment…][Dalit Female, 45 years old]

5.3.1. Muthi Daan

[…people don’t need to donate; they can donate whatever they can. We don’t mind if people do not donate this time; they can always donate next time when we meet up on Saturday…][Dalit Male, 25 years old]

[…We just get some money whatever we get out from our pocket. We don’t complain and ask for some of that money if they are making a small contribution. We do not have any children, and we feel happy to be able to support children in the church through donations. It’s good to give to other people, isn’t it?...][Dalit Female, 46 years old]

5.3.2. Dash Daan

[…I feel when I donate about 10 per cent of my salary because I know for the fact that this money will be very useful for our own community. This funding will enable to change people for better…][Dalit Male, 30 years old]

[…I found it very difficult to raise my children after the death of my husband. I am not very well, and I keep falling ill, and I cannot work as a labourer. I received some seed funding from the cchurch for goat farming. I was given a goat too. I am raising some pigs, goats, and chickens now. I have decent money. I have started to repay the loan on installments…][Dalit Female, 53 years old]

5.3.3. Educational Support

[…I even could not study during my childhood. I went to school, but I was not allowed to enter inside the classroom because of being a Dalit. I had to remain outside the classroom and clean the school premises instead. Upon conversion to Christianity, I could attend teaching in the church every morning. I can read the holy bible comfortably now. Even my grandson is also studying staying in the church hostel. They have told us that we can attend a bible college next year…][Dalit Male, 60 years old]

[…I was a local shaman in the village and was always interested in studying books. I got many religious books from Varanasi, and I used to read those books, hiding to avoid detection from the Brahmins. I was fluent in many religious texts. Once I converted to Christianity, I was able to study freely, and now I am also fluent in the holy bible. I can even translate and preach the holy bible to other people…][Dalit Male, 61 years old]

[…Before converting to Christianity, they used to say that a son of a cobbler cannot study, but instead I will become a ploughman. We were also poor and did not have much support, which is why our study suffered a lot. But, once we converted to Christianity we received a lot of encouragement and financial support from the church group. Therefore, our study slowly improved, and I completed my master’s degree. I work as a professional now…][Dalit Male, 37 years old]

[…After completing college education, I have been given the opportunity to attend a Bible college with all the facilities. And, I work as a gospel outreach officer in Ghorahi area …][Dalit Male, 26 years old]

5.4. Meeting Social, Emotional, and Spiritual Needs

[…I realised the benefit of spirituality and religious faith after retirement. After I started working for the local community as a President of the local temple management committee, we chant hymns, sing religious bhajan, which brings many elderly people together…][Dalit Male, 63 years old]

[…I feel satisfied and peaceful being a Christian, and sometimes I become very emotional during prayers. I share all my thoughts and feelings; I forget all my sorrows and troubles. I experience happiness deep inside me right from the soul with the god; I feel so relieved …][Dalit Female, 55 years old]

[…Children these days rather leave their elderly parents at the Pashupatinath temple because they take it so difficult to support them when they are alive and it’s hard for them to perform the last rituals when they die. Christian people do not have to worry about all these, as our funerals are organized by our local church…][Dalit Female, 45 years old]

5.5. Medical Support and Healings

[…We are Dalits, and on top of that I had leprosy. I was taken out of the village due to social taboos attached to leprosy. We had a tough time in those days. I was admitted to a mission hospital in Ghorahi, where I received all the treatments. My son was good at his study, and he was taken to Kathmandu to study medicine by a pastor. He works as a medical doctor in Kathmandu these days…][Dalit Female, 66 years old]

[…I did all the medication, and there is hardly any hospital where I did not attend. I was treated by shamans and done all sorts. But I still didn’t feel well. One of the local sisters prayed for me at the church and I felt good about it. We attend church together and I began to feel better gradually. I have no longer illness these days…][Dalit Female, 44 years old]

[…I was almost dead that day, really, if our local pastor had not taken me to the CATS office. I had tuberculosis, but no one had a clue about it. I had a bad chesty cough when I was at the church. I was advised by him to attend the CATS office where they not only gave medicine but also provided all the necessary food and vitamins. I recovered quickly from tuberculosis…][Dalit Male, 58 years old]

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alsop, Ian. 1996. Christians at the Malla Court: The Capuchin ‘piccolo libro’. In Change and Continuity: Studies in the Nepalese Culture of the Kathmandu Valley. Edited by Siegfried Lienhard. Torino: CESMEO, pp. 123–35. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Allan. 2004. Pentecostalism in Africa: An overview. ORITA: Ibadan Journal of Religious Studies 36: 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Apichella, Michael. 1996. Prison Pentecost. Eastbourne: Kingsway Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bankston, William B., Craig J. Forsyth, and H. Hugh Floyd. 1981. Toward a general model of the process of radical conversion: An interactionist perspective on the transformation of self-identity. Qualitative Sociology 4: 279–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, John. 2009. The Church in Nepal: Analysis of its Gestation and growth. International Bulletin of Missionary Research 33: 189–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Eileen. 1984. The Making of a Moonie. Oxford: Blackwell Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Bawa, Sylvia. 2019. Christianity, tradition, and gender inequality in postcolonial Ghana. African Geographical Review 38: 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckford, James A. 1997. The Transmission of Religion in Prison, Recherche. Sociologiques 28: 101–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beidelman, Thomas O. 1982. Colonial Evangelism: A Socio-Historical Study of an East African Mission at the Grassroots. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Lynn. 1985. Dangerous wives and sacred sisters: Social and symbolic roles of high-caste women in Nepal. Religious Studies 21: 246–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattachan, Krishna B., and Kailas N. Pyakuryal. 1996. The issue of national integration in Nepal: An ethnoregional approach. Occasional Papers in Sociology’ and Anthropology 5: 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattachan, Krishna B., Kamala Hemchuri, Yogendra Gurung, and Charkra Man Biswakarma. 2003. Existing Practices of Caste-Based Untouchability in Nepal and Strategy for a Campaign for Its Elimination. Kathmandu: ActionAid Nepal. [Google Scholar]

- Bishwakarma, Padmalal. 2004. The situation analysis for dalit women of Nepal. Paper presented at the National Seminar on Raising Dalit Participation in Governance Centre for Economic and Technical Studies, Lalitpur, Nepal, May 3–4; Kathmandu: Economic and Technical Studies in Cooperation Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld, Warren J. 2006. Christian privilege and the promotion of “secular” and not-so “secular” mainline Christianity in public schooling and in the larger society. Equity & Excellence in Education 39: 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Boerema, Albert J. 2011. A Research Agenda for Christian Schools. Journal of Research on Christian Education 20: 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Mary M. 1998. On the Edge of the Auspicious: Gender and Caste in Nepal. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Ben. 2016. Tamang Christians and the Resituating of Religious Difference. In Religion, Secularism, and Ethnicity in Contemporary Nepal, 1st ed. Edited by David N. Gellner, Sondra L. Hausner and Chiara Letizia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 403–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cartledge, Mark J. 2013. Pentecostal healing as an expression of godly love: An empirical study. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 16: 501–22. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2001. Census Report, Nepal; Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2011. Census Report, Nepal; Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Cruz, Joel Morales. 2014. The Histories of the Latin American Church: A Handbook. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- DDC. 2018. District Profile of Dang District. Ghorahi: District Development Committee, Dang. [Google Scholar]

- Derné, Steve. 2012. Men’s sexuality and women’s subordination in Indian nationalisms. In Gender Ironies of Nationalism. London: Routledge, pp. 251–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, Kamal. 2014. Conversion into Christianity in Nepal: A Way to Break Down the Social and Cultural Hierarchy. Master’s thesis, The University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, Michael, and Laura Nuzzi O’Shaughnessy. 2000. Nicaragua’s Other Revolution: Religious Faith and Political Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doja, Albert. 2000. The politics of religion in the reconstruction of identities: The Albanian situation. Critique of Anthropology 20: 421–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, Assa, and Alex Broom. 2013. Health, Culture and Religion in South Asia: Critical Perspectives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, Louis. 1980. Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, John L. 2002. A History of Christian Education: Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox Perspectives. Malabar: Krieger Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, Annelin. 2012. The pastor and the prophetess: An analysis of gender and Christianity in Vanuatu. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falla, Ricardo. 2001. Quiché Rebelde: Religious Conversion, Politics, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Leela. 2011. Unsettled territories: State, civil society, and the politics of religious conversion in India. Politics and Religion 4: 108–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, Leslie A. 2019. Women’s Work for Women: Missionaries and Social Change in Asia. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- FNCN. 2012. Christian population below actual size. Kathmandu Post. December 6. Available online: https://kathmandupost.com/news/2012-12-05/fncn-christian-population-below-actual-size.html (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Foddy, William, and William H. Foddy. 1994. Constructing Questions for Interviews and Questionnaires: Theory and Practice in Social Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michael. 2002. The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fountain, Philip. 2015. Proselytizing development. In The Routledge Handbook of Religions and Global Development. London: Routledge, pp. 94–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fricke, Tom. 2008. Tamang conversions: Culture, politics, and the Christian conversion narrative in Nepal. Journal of Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies 35: 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric. 2008. Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gellner, David N. 2007. Caste, ethnicity and inequality in Nepal. Economic and Political Weekly 42: 1823–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorahi Municipality. 2018. Annual Publication of Ghorahi Sub-Metropolitan Municipality. Ghorahi: Ghorahi Sub-Metropolitan Municipality Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Ian. 2019. Praying for Peace: Family Experiences of Christian Conversion in Bhaktapur. HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies 39: 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1968. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Piscataway: AldineTransaction. [Google Scholar]

- Goosby, Bridget J., Jacob E. Cheadle, and Colter Mitchell. 2018. Stress-related biosocial mechanisms of discrimination and African American health inequities. Annual Review of Sociology 44: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary. 2013. Christianity in Its Global Context, 1970–2020: Society, Religion and Mission. South Hamilton: Center for the Study of Global Christianity. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20180922211444/https://www.gordonconwell.edu/ockenga/research/documents/ChristianityinitsGlobalContext.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Grant, Colin. 2000. Altruism and Christian Ethics 18. London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greil, Arthur L., and David R. Rudy. 1983. Conversion to the world view of Alcoholics Anonymous: A refinement of conversion theory. Qualitative Sociology 6: 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grier, Robin. 1997. The effect of religion on economic development: A cross national study of 63 former colonies. Kyklos 50: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Michael. 2003. Previous Convictions: Conversion in the Present Day. Evangelical Quarterly: An International Review of Bible and Theology 75: 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudem, Wayne. 1994. An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine: Systematic Theology. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Angelina L. 2009. The preferential option for the poor in Catholic education in the Philippines: A report on progress and problems. International Studies in Catholic Education 1: 135–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, Catherine. 2000. Research Design: Successful Designs for Social and Economic Research, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, Anne. 2019. Student/teachers from Turfloop: The propagation of Black Consciousness in South African schools, 1972–76. Africa 89: 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindmarsh, Bruce. 2014. Religious Conversion as Narrative and Autobiography. In The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Edited by Lewis R. Rambo and Charles E. Farhadian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, David R., Robin P. Bonifas, and Rita Jing-Ann Chou. 2010. Spirituality and older adults: Ethical guidelines to enhance service provision. Advances in Social Work 11: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, Katharina. 2003. The role of evangelical NGOs in international development: A comparative case study of Kenya and Uganda. Africa Spectrum, 375–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Ralph W., Jr., Peter C. Hill, and Bernard Spilka. 2018. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach, 5th ed. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Idler, Ellen. 2008. The psychological and physical benefits of spiritual/religious practices. Spirituality in Higher Education Newsletter 4: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, Kenneth. 1956. Reformers in India 1793–833: An Account of the Work of Christian Missionaries on Behalf of Social Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, Sriya. 2010. Religion and economic development. In Economic Growth. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 222–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jindra, Ines W. 2014. A New Model of Religious Conversion: Beyond Network Theory and Social Constructivism. Leiden: Brill Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kehrberg, Norma. 2000. The Cross in the Land of the Khukuri. Kathmandu: Ekta Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kharel, Sambriddhi. 2010. The Dialectics of Identity and Resistance among Dalits in Nepal. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchheiner, Ole. 2016. Culture and Christianity Negotiated in Hindu Society: A Case Study of a Church in Central and Western Nepal. Doctoral dissertation, Middlesex University, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kisan, Yam B. 2005. The Nepali Dalit Social Movement. Kathmandu: Legal Rights Protection Society. [Google Scholar]

- Klingorova, Kamila, and Tomáš Havlíček. 2015. Religion and gender inequality: The status of women in the societies of world religions. Moravian Geographical Reports Moravian Geographical Reports 23: 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klau. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, Richard A. 2014. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kurian, George Thomas. 2012. Ecuadorian Christianity. In The Encyclopaedia of Christian Civilization. London: Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, Christopher, and M. Darroll Bryant. 1999. Religious Conversion: Contemporary Practices and Controversies. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Landon, Perceval. 1928. Nepal. London: Constable and Co., vol. 2, p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Lawoti, Mahendra. 2005. Towards a Democratic Nepal: Inclusive Political Institutions for a Multicultural Society. Delhi: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lawoti, Mahendra, and Susan Hangen. 2013. Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict in Nepal: Identities and Mobilization after 1990. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Letizia, Chiara. 2012. Shaping secularism in Nepal. European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 39: 66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland, John, and Rodney Stark. 1965. Becoming a world saver: A theory of conversion to a deviant perspective. American Sociological Review 30: 862–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Theodore E., and Jeffrey K. Hadden. 1983. Religious Conversion and the Concept of Socialisation: Integrating the Brainwashing and Drift Models. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 22: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzen, David N. 2003. Europeans in late Mughal south Asia: The perceptions of Italian missionaries. The Indian Economic & Social History Review 40: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maruna, Shadd, Louise Wilson, and Kathryn Curran. 2006. Why God is often found behind bars: Prison conversions and the crisis of self-narrative. Research in Human Development 3: 161–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., and Brian L. B. Willoughby. 2009. Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin 135: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, Alister E. 2012. Mere Apologetics: How to Help Seekers and Skeptics Find Faith. London: Baker Books. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 1996. Religion and healing the mind/body/self. Social Compass 43: 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, George Herbert. 1967. Mind, Self and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mushi, Philemon Andrew K. 2009. History and Development of Education in Tanzania. African books collective. Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Taylor, and Daniel McIntosh. 2013. Unique Contributions of Religion toMeaning. In The Experience of Meaning in Life: Classical Perspectives, Emerging Themes, and Controversies. Edited by Joshua A. Hicks and Clay Routledge. Dordrecht, Heidelberg and New York: Springer, pp. 257–70. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo, Lluis. 2019. Meaning and Religion: Exploring Mutual Implications. Scientia et Fides 7: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloutzian, Raymond F., James T. Richardson, and Lewis R. Rambo. 1999. Religious conversion and personality change. Journal of Personality 67: 1047–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, Biswo Kallyan. 2007. Occupational change among the Gaines of Pokhara City. In Nepalis Inside and Outside Nepal. Edited by Ishii Hiroshi, David N. Gellner and Katsuo Nawa. Delhi: Manohar, pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pariyar, Bishnu, and Jon C. Lovett. 2016. Dalit identity in urban Pokhara, Nepal. Geoforum 75: 134–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrucci, Dennis J. 1968. Religious Conversion: A Theory of Deviant Behavior. Sociology of Religion 29: 144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, George. 2018. Covenant, Promise, and the Gift of Time. Religious Inquiries 7: 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Peace, Richard V. 2004. Conflicting understandings of Christian conversion: A missiological challenge. International Bulletin of Missionary Research 28: 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, Dennis L. 1987. Religious Conviction among Non-Parolable Prison Inmates. Corrective and Social Psychiatry and Journal of Behaviour Technology Methods and Therapy 33: 165–74. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Cindy L. 1990. A Biographical History of the Church in Nepal, 3rd ed. Kathmandu: Nepal Church History Project, pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Racine, Karen. 2008. Commercial Christianity: The British and Foreign Bible Society’s Interest in Spanish America, 1805–1830. Informal Empire in Latin America: Culture, Commerce and Capital, 78–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, Lagan. 2017. Conversion to Christianity through labour migrant. In Kinship Studies in Nepali Anthropology. Edited by Uprety Laya Prasad, Binod Pokharel and Suresh Dhakal. Kinship Studies in Nepali Anthropology. Kathmandu: Central Department of Anthropology, Tribhuvan University. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, Lewis R. 1993. Understanding Religious Conversion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Barry. 1978. The Experience of Long-Term Imprisonment-An Exploratory Investigation. British Journal of Criminology 18: 162–69. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, James T. 1985. The active vs. passive convert: Paradigm conflict in conversion/recruitment research. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 1985: 163–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Rowena, and Joseph Marianus Kujur, eds. 2010. Margins of Faith: Dalit and Tribal Christianity in India. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. [Google Scholar]

- Romain, Jonathan A. 2000. Your God Shall Be My God: Religious Conversion in Britain Today. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Don. 2008. Christian schools-a world of difference. TEACH Journal of Christian Education 2: 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Saiya, Nilay, and Stuti Manchanda. 2020. Anti-conversion laws and violent Christian persecution in the states of India: A quantitative analysis. Ethnicities 20: 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Bal Krishna. 2001. A history of the Pentecostal movement in Nepal. Asian Journal of Pentecostal Studies 4: 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Shellnutt, Kate. 2017. Nepal Criminalizes Christian Conversion and Evangelism. Christianity Today 25. Available online: https://runwiththeword.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Nepal-News-Alert.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2020).

- Singer, Merrill, and Pamela I. Erickson. 2013. Global Health: An Anthropological Perspective. Long Grove: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Margaret Thaler, and Janja Lalich. 1995. Cults in Our Midst. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass/Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Skotnicki, Andrew. 1996. Religion and Rehabilitation. Criminal Justice Ethics 15: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, David A., and Richard Machalek. 1984. The sociology of conversion. Annual Review of Sociology 10: 167–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sob, Durga. 2012. The Situation of the Dalits in Nepal Prospects in a New Political Reality. Voice of Dalit. Kathmandu: MD Publication Pvt. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, David W., and Prem N. Shamdasani. 2014. Focus Groups, Theory and Practice. London: Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Stronge, Samantha, Joseph Bulbulia, Don E. Davis, and Chris G. Sibley. 2021. Religion and the development of character: Personality changes before and after religious conversion and deconversion. Social Psychological and Personality Science 12: 801–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, Gresham M. 2021. The Society of Captives. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thumma, Scott. 1991. Seeking to be Converted: An Examination of Recent Conversion Studies and Theories. Pastoral Psycholog 39: 185–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timor, Un. 1998. Constructing a rehabilitative reality in special religious wards in Israeli prisons. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 42: 340–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travisano, Richard V. 1970. Alternation and conversion as qualitatively different transformations. In Social Psychology Through Symbolic Interaction. Edited by Gregory Prentice Stone and Harvey A. Farberman. Waltham: Ginn-Blaisdell, pp. 594–606. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Bryan S. 2013. The Religious and the Political: A Comparative Sociology of Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, Helen. E. 2019. Discussion and Conclusion Reflections on the Impact of Education in South Asia: From Sri Lanka to Nepal. In The Impact of Education in South Asia. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 287–97. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, Prakash. 2020. Restructuring Spiritualism in New Life: Conversion to Christianity in Pokhara, Nepal. Janapriya Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 9: 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department. 2018. 2018 Report on International Religious Freedom: Nepal. United States Department of State. Available online: https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-report-on-international-religious-freedom/nepal/ (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Villa-Vicencio, Charles, and Peter Grassow. 2009. Christianity and the Colonisation of South Africa, 1487–1883: A Documentary History. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wankhede, Harish S. 2009. The Political Context of Religious Conversion in Orissa. Economic and Political Weekly 44: 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Peter J., and Peter G. Coleman. 2010. Strong beliefs and coping in old age: A case-based comparison of atheism and religious faith. Ageing & Society 30: 337–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 1998. Spiritual conversion: A study of religious change among college students. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 161–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Number and Location of Key Informant Interviews and Focus Group Discussions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Informants | Informants/Kuragraphy | Focus Group | Discussions | ||||

| Pratapi Church (Bharatpur) | Ghorahi Susamachar Church (Rajhena) | Balidaan Church (Lohasur) | Anugraha Church (Rangara) | Jyoti Church (Shewar Khola) | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 6 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Female | 4 | 26 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Caste | |||||||

| Dalits | 10 | 41 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Occupation | |||||||

| Traditional occupation | 2 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Housewife | 3 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Daily wage labour | 8 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |

| Student | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Businessman | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Pastor | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Government Officer | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Teacher | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 5 | 26 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Unmarried | 2 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Intercaste married | 1 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Widow | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Level of Education | |||||||

| Illiterate | 1 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| School Level | 5 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| College Level | 4 | 19 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Total | 10 | 41 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pariyar, B.; Chhinal, S.; Thapa Magar, S.; Bisunke, R. Pedalling Out of Sociocultural Precariousness: Religious Conversions amongst the Hindu Dalits to Christianity in Nepal. Religions 2021, 12, 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100856

Pariyar B, Chhinal S, Thapa Magar S, Bisunke R. Pedalling Out of Sociocultural Precariousness: Religious Conversions amongst the Hindu Dalits to Christianity in Nepal. Religions. 2021; 12(10):856. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100856

Chicago/Turabian StylePariyar, Bishnu, Sushma Chhinal, Shyamu Thapa Magar, and Rozy Bisunke. 2021. "Pedalling Out of Sociocultural Precariousness: Religious Conversions amongst the Hindu Dalits to Christianity in Nepal" Religions 12, no. 10: 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100856

APA StylePariyar, B., Chhinal, S., Thapa Magar, S., & Bisunke, R. (2021). Pedalling Out of Sociocultural Precariousness: Religious Conversions amongst the Hindu Dalits to Christianity in Nepal. Religions, 12(10), 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100856