Mapping Instructional Barriers during COVID-19 Outbreak: Islamic Education Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 and Education

2.2. COVID-19 and Indonesian Education

2.3. Pesantren

2.4. Studies on Barriers in Distance Education during COVID-19

3. Method

3.1. Procedures and Participants

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3. Choosing a Tool for Qualitative Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Technological Barriers

“Students from rural areas have trouble in using the Internet for distance learning. Internet access is good in the city center; however, when someone stays in a rural area, the access is horrible”, (U2)

“Most students in my Pesantren are from rural areas, and it is hard for them to get access. For example, one of my students who live in a mountainous area should go to a certain higher place to be able to contact me via video calls”, (U5)

“The problem is not only faced by students but also teachers who live in rural areas. They have limited access to the Internet”. (U1)

“I am still new in using the e-learning platform on my smartphone. I had no idea what Zoom looks like. Even though I have already understood the application, my students are still alienated from it. So, we can’t use it. We just use WhatsApp during assessment submission”. (U4)

“In Pesantren, students are not allowed to use smartphones. Thus, I can not guarantee they ca use it during the pandemic. Two of my students even do not know how to use WhatsApp”. (U6)

4.2. Financial Barriers

“Limited financial support was provided by the government amidst the pandemic. Especially when the students want to buy internet packages”, (U7)

“The students are majorly from families whose parents are farmers. Even before the pandemic, the economy was difficult for them. As a result, their ability to buy internet packages is the holdback in facilitating students during distance learning”. (U3)

“I have to do other jobs to support my family. I have three children, and they have to survive in this situation. Besides my job as a teacher, I have to do carpentry. To consider buying internet packages is something I cannot manage”. (U6)

“I got a pay cut almost 30% from the Pesantren I work. It is a very difficult and I have to look for other sources for supporting my family. It affects the distance learning”. (U3)

“The salary cut is tough. Even with a normal situation, our stipend from Pesantren is not sufficient; we can not make our lives better financially. With three children, it is not enough”. (U2)

4.3. Pedagogical Barriers

“Regarding the pedagogy, I think one of the barriers is our weaknesses to deliver the content of the learning materials. During face-to-face education, we can analyze the situation of the class, the mood of the students, and the dynamic of the content delivery. We can not do those three factors during online learning. Thus, the quality of the delivery for me is a bit lowered”, (U1)

“It is important to have an effective presentation during teaching and learning process. I have difficulties in this thing during distance learning during COVID-19. With the absence of face-to-face meetings, it is difficult for me to have an effective and efficient instructional presentation”. (U4)

“When I teach online or in the distance, it is hard to order the learning activities. It is even harder with the limited facilities and funding we have during distance. In a normal situation, we can structure our activities in accordance with the lesson plan”. (U5)

“In face-to-face meetings, social interaction is built in a comprehensive way; students can directly interact with both teachers and peers. In this kind of situation, it cannot be done since we do not meet physically”, (U2)

“There is no social interaction between students and students as well as between students and teachers. The teaching and learning process can be run effectively if this condition continues. We need to give feedback, encouragement, and evaluation better if we meet in face-to-face meetings”, (U6)

“Pesantren is a community-based school where students interaction can be 24 h; they learn religious objects in the afternoon and night and national curriculum in the morning. During the pandemic, the absence of this kind of interaction makes pedagogical activities harder”. (U5)

4.4. Suggestions

“It is important to have good access to the internet during the school closure during the pandemic. I hope that the government can improve the infrastructures, especially in rural areas”. (U2)

“I am not really at using technology for teaching. So, training is needed for me on how to use technology for pedagogical activities. I even need to know how to use some unfamiliar technologies, like Zoom and Edmodo”. (U3)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abidah, Azmil, Hasan Nuruul Hidaayatullaah, Roy Martin Simamora, Daliana Fehabutar, and Lely Mutakinati. 2020. The Impact of Covid-19 to Indonesian Education and Its Relation to the Philosophy of “Merdeka Belajar”. Studies in Philosophy of Science and Education 1: 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhammad, Sawsan. 2020. Barriers to distance learning during the COVID-19 outbreak: A qualitative review from parents’ perspective. Heliyon 6: e05482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Faqir, Anisya. 2020. Kemendikbud Catat 646.200 Sekolah Tutup Akibat Virus Corona [Ministry of Education and Culture Records 646,200 Schools Closed Due to Corona Virus]. Available online: https://www.merdeka.com/uang/kemendikbud-catat-646200-sekolah-tutup-akibatvirus-corona (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Almanthari, Abdulsalam, Suci Maulina, and Sandra Bruce. 2020. Secondary School Mathematics Teachers’ Views on E-learning Implementation Barriers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Indonesia. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 16: em1860. [Google Scholar]

- Almazova, Nadezhda, Elena Krylova, Anna Rubtsova, and Maria Odinokaya. 2020. Challenges and opportunities for Russian higher education amid COVID-19: Teachers’ perspective. Education Sciences 10: 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amozurrutia, Jose, and Chaime Marcuello Servós. 2011. Excel spreadsheet as a tool for social narrative analysis. Quality and Quantity 45: 953–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baticulon, Ronnie, Nicole Rose Alberto, Maria Beatrize Baron, Robert Earl Mabulay, Lloyd Gabriel Rizada, Jinno Jenkin Sy, Christl Jan Tiu, Charlie Clarion, and John Carlo Reyes. 2020. Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19: A national survey of medical students in the Philippines. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BNPB. 2020. Peta Sebaran COVID-19 [Spread Mapping of Covid-19]. Available online: https://covid19.go.id/peta-sebaran (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Chenail, Ronald. 2012. Conducting qualitative data analysis: Reading line-by-line, but analyzing by meaningful qualitative units. The Qualitative Report 17: 266–69. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Joseph, Kerryn Butler-Henderson, Jurgen Rudolph, Bashar Malkawi, Matt Glowatz, Rob Burton, Paola Magni, and Sophia Lam. 2020. COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Teaching and Learning (JALT) 3: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John Ward. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John Ward. 2012. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed. Boston: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Dhofier, Zamakhsyari. 1982. Tradisi Pesantren: Studi Tentang Pandangan Hidup Kyai [Pesantren Tradition: Study of the Life Outlook of the Kyai]. Jakarta: LP3ES. [Google Scholar]

- Eames, Ken, Nathasa Louise Tilston, Peter J. White, Elisabeth Jane Adams, and John Edmunds. 2010. The impact of illness and the impact of school closure on social contact patterns. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 14: 267–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eames, Ken, Nathasa Louise Tilston, and John Edmunds. 2011. The impact of school holidays on the social mixing patterns of school children. Epidemics 3: 103–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsevier. 2020. Novel Corona Virus Information Center. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/coronavirus-information-center (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Habibi, Akhmad, Amirul Mukminin, Johny Najwan, Septu Haswindy, Lenny Marzulina, Muhammad Sirozi, Kasinyo Harto, and Muhammad Sofwan. 2018. Investigating EFL classroom management in Pesantren: A case study. The Qualitative Report 23: 2105–22. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, Akhmad, Rafiz Abdul Razak, Farrah Dina Yusop, Amirul Mukminin, and Lalu Nurul Yaqin. 2020. Factors Affecting ICT Integration During Teaching Practices: A Multiple Case Study of Three Indonesian Universities. The Qualitative Report 25: 1127–44. [Google Scholar]

- Isbah, Falikul. 2020. Pesantren in the changing Indonesian context: History and current developments. Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies 8: 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Amit, Muddu Vinay, and Preeti Bhaskar. 2020. Impact of coronavirus pandemic on the Indian education sector: Perspectives of teachers on online teaching and assessments. Interactive Technology and Smart Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapproth, Florian, Lisa Federkeil, Franziska Heinschke, and Tanja Jungmann. 2020. Teachers’ experiences of stress and their coping strategies during COVID-19 induced distance teaching. Journal of Pedagogical Research 4: 444–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Pelle, Nancy. 2004. Simplifying qualitative data analysis using general purpose software tools. Field Methods 16: 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, Stephen A., Kyra Grantz, Qifang Bi, Forrest Jones, Qulu Zheng, Hannah Meredith, Andrew Azman, Nicholas Reich, and Justin Lessler. 2020. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: Estimation and application. Annals of Internal Medicine 172: 577–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Yvonna.Y, and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, Sharan B. 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Daniel Z., and Leanne M. Avery. 2009. Excel as a qualitative data analysis tool. Field Methods 21: 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukminin, Amirul, and Brenda J. McMahon. 2013. International Graduate Students’ Cross-Cultural Academic Engagement: Stories of Indonesian Doctoral Students on American Campus. The Qualitative Report 18: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mukminin, Amirul, Raden M. Ali, and Muhammad J. Ashari. 2015. Voices from within: Student teachers’ experiences in english academic writing socialization at one Indonesian teacher training program. The Qualitative Report 20: 1394–407. [Google Scholar]

- Muttaqin, Tatang. 2018. Determinants of unequal access to and quality of education in Indonesia. The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning 2: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilan, Pam. 2007. The ‘spirit of education’ in Indonesian Pesantren. British Journal of Sociology of Education 30: 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primdahl, Nina Langer, Anne Sofie Borsch, An Verelst, Signe Smith Jervelund, Ilse Derluyn, and Morten Skovdal. 2020. ‘It’s difficult to help when I am not sitting next to them’: How COVID-19 school closures interrupted teachers’ care for newly arrived migrant and refugee learners in Denmark. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prujit, Hans. 2012. Interview streamliner, a minimalist, free, open source, relational approach to computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software. Social Science Computer Review 30: 248–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Gary W. 2004. Using a Word processor to tag and retrieve blocks of text. Field Methods 16: 109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofwan, Muhammad, and Akhmad Habibi. 2016. Problematika dunia pendidikan Islam abad 21 dan tantangan pondok Pesantren di Jambi [Problems in the world of 21st century Islamic education and the challenges of Islamic boarding schools in Jambi]. Jurnal Kependidikan [Education Journal] 46: 271–80. [Google Scholar]

- Srimulyani, Eka. 2007. Muslim women and education in Indonesia: The pondok pesantren experience. Asia Pacific Journal of Education 27: 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. 2020a. Education: From Disruption to Recovery. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- UNICEF. 2020b. Learning from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/coronavirus/stories/learning-home-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Van Lancker, Wim Pan, and Zachary Parolin. 2020. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health 5: e243–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajdi, Muh Barid Nizarudin, Iwan Kuswandi, Umar Al Faruq, Zulhijra Zulhijra, Khairudin Khairudin, and Khoiriyah Khoiriyah. 2020. Education Policy Overcome Coronavirus, A Study of Indonesians. EDUTEC: Journal of Education and Technology 3: 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Guanghai, Yunting Zhang, Jin Zhao, Jun Zhang, and Fan Jiang. 2020. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet 395: 945–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, Moh Asror, and Ahmad Taufiq. 2020. The dynamic views of Kiais in response to the government regulations for the development of Pesantren. Qudus International Journal of Islamic Studies 8: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | Method | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| (Almanthari et al. 2020) | Survey on 159 Indonesia students | School level barriers |

| Curriculum level barriers | ||

| (Joshi et al. 2020) | Interview with teachers in India | Online teaching and assessments, home environment settings |

| Institutional support for online teaching and assessments | ||

| Technical difficulties faced by teachers in online teaching and assessments | ||

| Personal problems faced by teachers in online teaching and assessments | ||

| (Baticulon et al. 2020) | Survey with 3421 medical students in the Philippine | Technological barriers |

| Individual barriers | ||

| Domestic barriers | ||

| Community barriers | ||

| (Abuhammad 2020) | Review analysis of 288 student parents’ posts from Facebook groups in Jordan | Personal barriers |

| Technical barriers | ||

| Logistical barriers | ||

| Financial barriers | ||

| (Klapproth et al. 2020) | Cross-sectional study on 380 teachers in Germany | Level of stress |

| Teaching time | ||

| Technical barriers | ||

| (Primdahl et al. 2020) | Interview with eight teachers in Danish preparatory classes | Virtual communication platforms barriers and |

| Language barriers | ||

| (Almazova et al. 2020) | Survey with 87 university teachers | Computer literacy level |

| The university electronic environment and support | ||

| Academic staff readiness and students’ readiness for online learning |

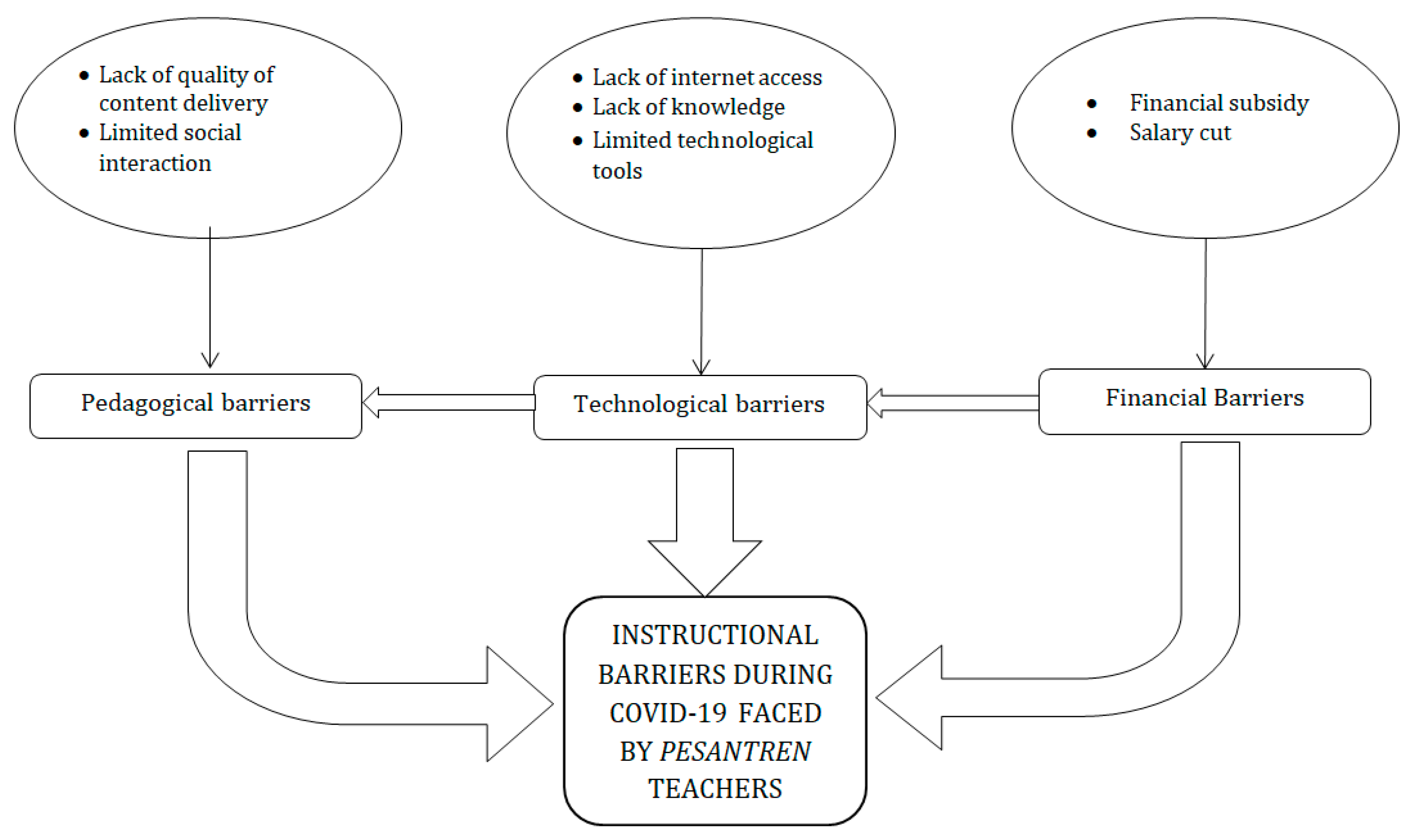

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| 1. Technological barriers | (a) Lack of internet access |

| (b) Lack of knowledge | |

| (c) Limited technological tools | |

| 2. Financial barriers | (a) Financial subsidy |

| (b) Salary cut | |

| 3. Pedagogical barriers | (a) Lack of quality of content delivery |

| (b) Limited social interaction | |

| 4. Suggestions | (a) Improvement of infrastructures |

| (b) Financial aid | |

| (c) Teaching training |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Habibi, A.; Mukminin, A.; Yaqin, L.N.; Parhanuddin, L.; Razak, R.A.; Nazry, N.N.M.; Taridi, M.; Karomi, K.; Fathurrijal, F. Mapping Instructional Barriers during COVID-19 Outbreak: Islamic Education Context. Religions 2021, 12, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010050

Habibi A, Mukminin A, Yaqin LN, Parhanuddin L, Razak RA, Nazry NNM, Taridi M, Karomi K, Fathurrijal F. Mapping Instructional Barriers during COVID-19 Outbreak: Islamic Education Context. Religions. 2021; 12(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleHabibi, Akhmad, Amirul Mukminin, Lalu Nurul Yaqin, Lalu Parhanuddin, Rafiza Abdul Razak, Nor Nazrina Mohamad Nazry, Muhamad Taridi, Karomi Karomi, and Fathurrijal Fathurrijal. 2021. "Mapping Instructional Barriers during COVID-19 Outbreak: Islamic Education Context" Religions 12, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010050

APA StyleHabibi, A., Mukminin, A., Yaqin, L. N., Parhanuddin, L., Razak, R. A., Nazry, N. N. M., Taridi, M., Karomi, K., & Fathurrijal, F. (2021). Mapping Instructional Barriers during COVID-19 Outbreak: Islamic Education Context. Religions, 12(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010050