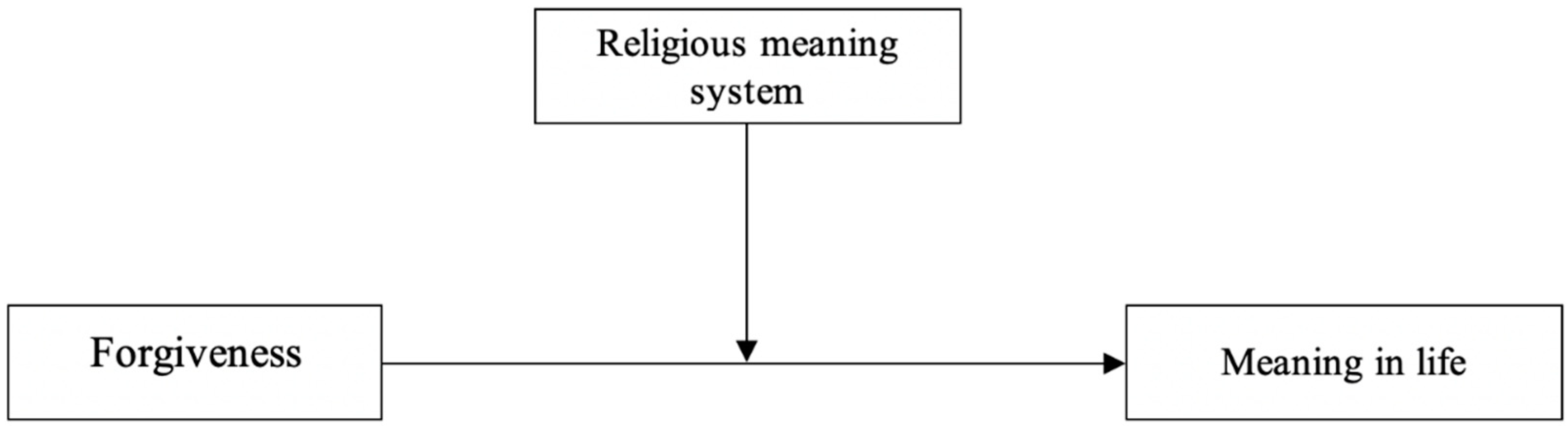

Interpersonal Forgiveness and Meaning in Life in Older Adults: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of the Religious Meaning System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations Scale (TRIM)

2.2.2. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ)

2.2.3. The Religious Meaning System Questionnaire (RMS)

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses Subsection

3.2. Mediational Analyses

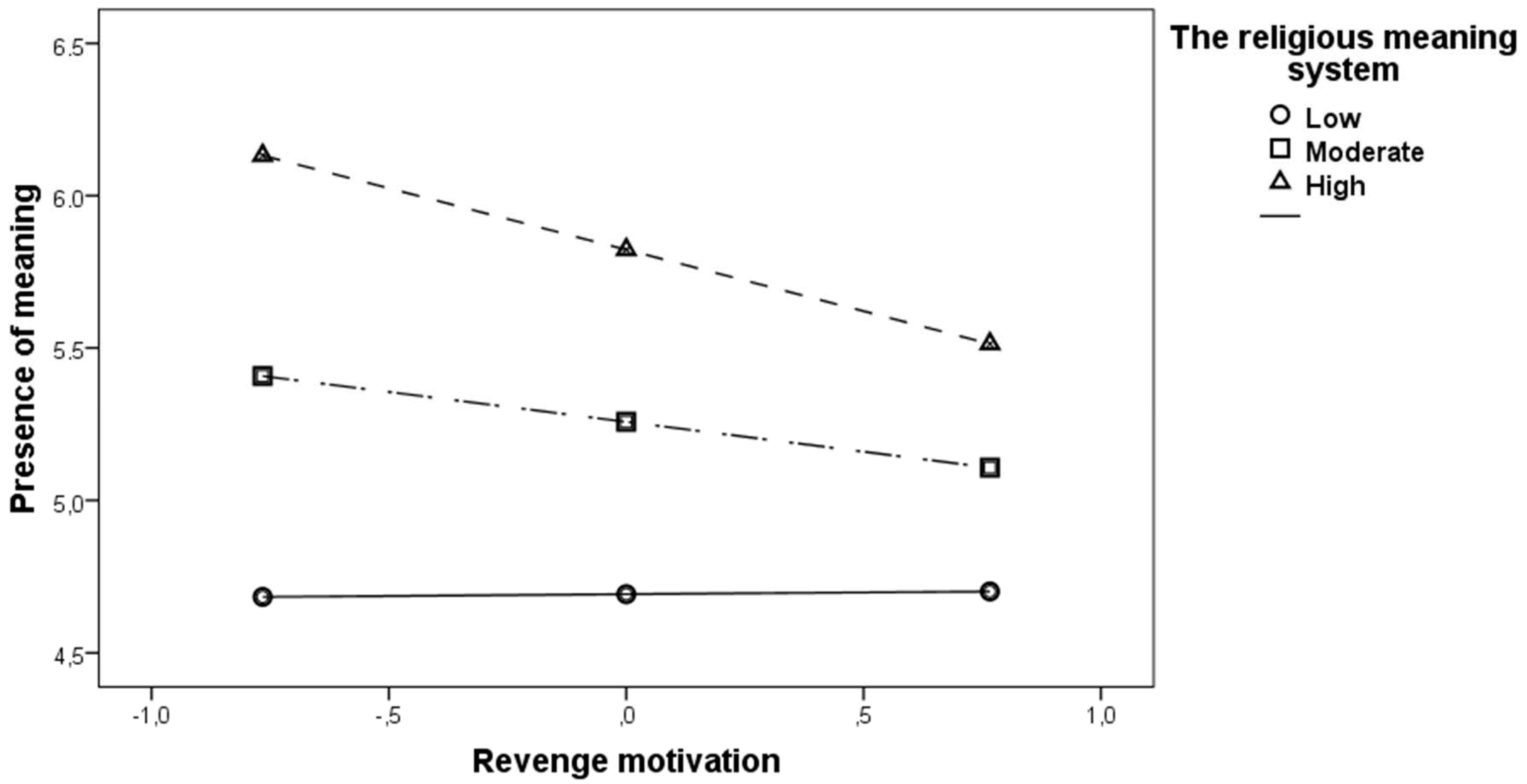

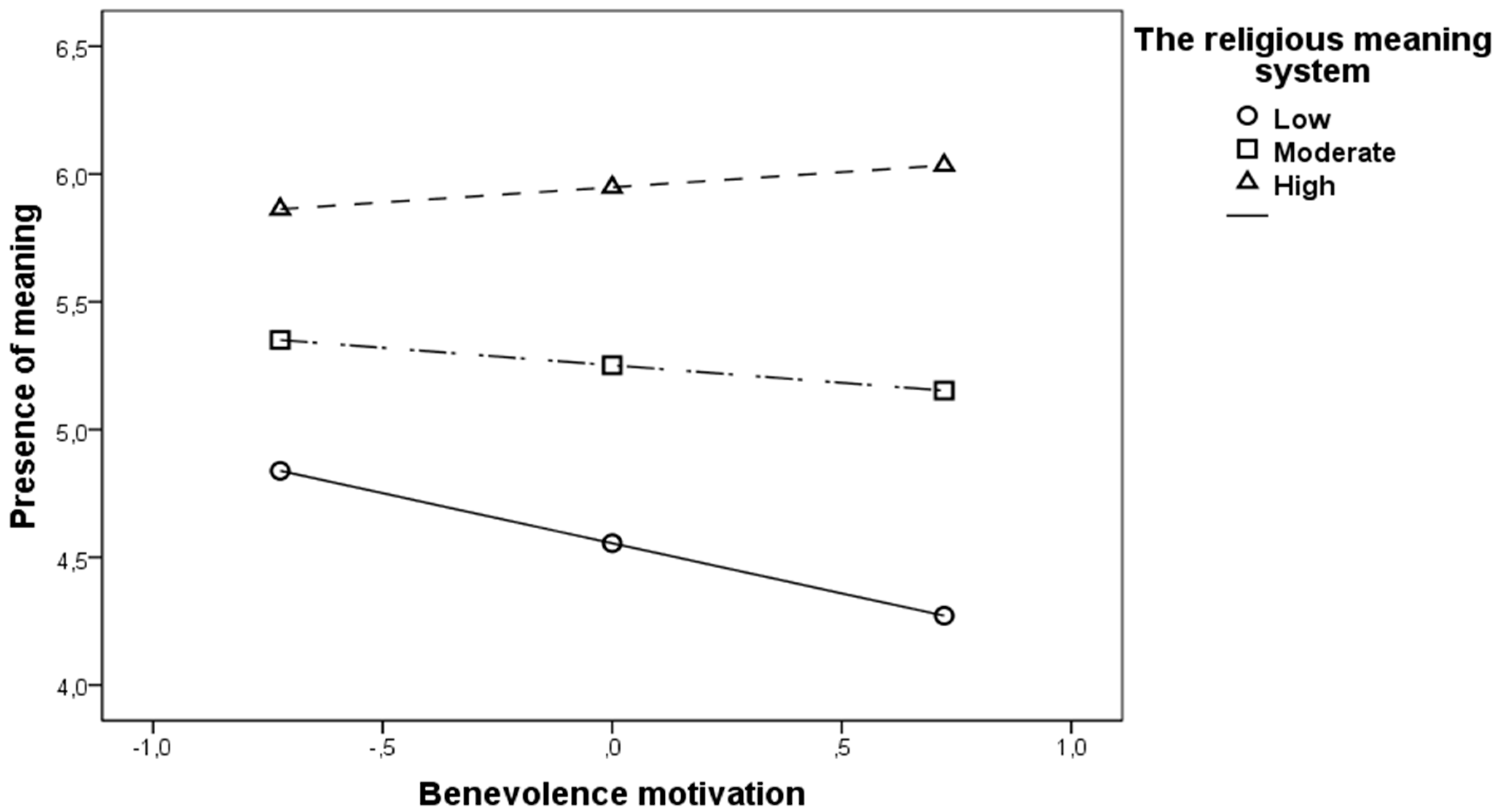

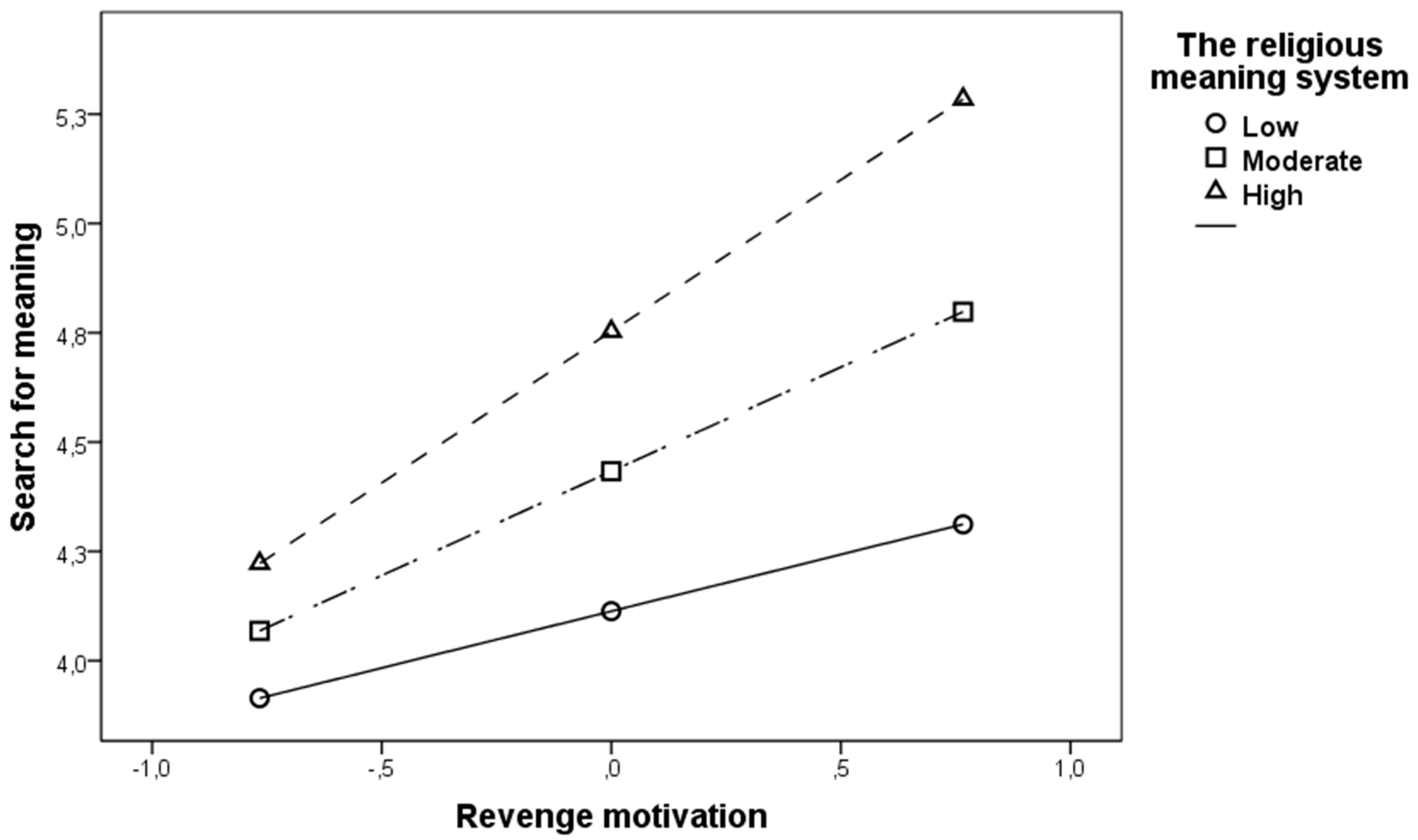

3.3. Moderation Analyses

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, Ryan P. 2003. Measuring Individual Differences in the Tendency to Forgive: Construct Validity and Links with Depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29: 759–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ying, Sion Kim Harris, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., and Tyler J. VanderWeele. 2019. Religiously or Spiritually-Motivated Forgiveness and Subsequent Health and Well-Being among Young Adults: An Outcome-Wide Analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 14: 649–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Don E., Joshua N. Hook, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, and Everett L. Worthington, Jr. 2012. Sanctification of Forgiveness. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4: 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Don E., Man Yee Ho, Brandon J. Griffin, Chris Bell, Joshua N. Hook, Daryl R. Van Tongeren, Cirleen DeBlaere, Everett L. Worthington, and Charles J. Westbrook. 2015. Forgiving the Self and Physical and Mental Health Correlates: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Counseling Psychology 62: 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdaele, Elke, Loren Toussaint, Evalyne Thauvoye, and Jessie Dezutter. 2019. Forgiveness and Late Life Functioning: The Mediating Role of Finding Ego-Integrity. Aging & Mental Health 23: 238–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A. 2005. Emotion and Religion. In Handbook of Thepsychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 235–52. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, Robert, Susan Freedman, and Joanna Rique. 1998. The Psychology of Interpersonal Forgiveness. In Exploring Forgiveness, edited by Robert Enright and Joanna North. Madison: University of Wisconsin, pp. 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik. 1959. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York: International University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Ann Marie Yali, and Marci Lobel. 1999. When God Disappoints Difficulty Forgiving God and Its Role in Negative Emotion. Journal of Health Psychology 4: 365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbons, Richard P. 1986. The Cognitive and Emotive Uses of Forgiveness in the Treatment of Anger. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 23: 629–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, Viktor. 1962. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Głaz, Stanisław. 2019. The Relationship of Forgiveness and Values with Meaning in Life of Polish Students. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 1886–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantman, Shira, and Orna Cohen. 2010. Forgiveness in Late Life. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 53: 613–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Peter C., and Evonne Edwards. 2013. Measurement in the Psychology of Religiousness and Spirituality: Existing Measures and New Frontiers. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and James W. Jones. APA Handbooks in Psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Ralph W., Peter C. Hill, and Bernard Spilka. 2009. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach, 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S., Marie Allemand, and Odilo W. Huber. 2011. Forgiveness by God and Human Forgivingness: The Centrality of the Religiosity Makes the Difference. Archiv Für Religionspsychologie/Archive for the Psychology of Religion 33: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan. 2007. Are Religious Beliefs Relevant in Daily Life? In Religion Inside and Outside Traditional Institutions. Edited by Heinz Streib. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2008. Kerndimensionen, Zentralität und Inhalt. Ein Interdisziplinäres Modell der Religiosität. Journal für Psychologie 16: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossakowska, Marlena, Piotr Kwiatek, and Tomasz Stefaniak. 2014. Sens w życiu. Polska wersja kwestionariusza MLQ (Meaning in Life Questionnaire). Psychology of Quality of Life 12: 111–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal. 2004. Stressors arising in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 59: S287–S97. [Google Scholar]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2009. Religijność a Jakość Życia w Perspektywie Mediatorów Psychospołecznych. Opole: Redakcja Wydawnictw Wydziału Teologicznego Uniwersytetu Opolskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2014. The Religious Meaning System and Subjective Well-Being. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 36: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2015. The Role of Meaning in Life Within the Relations of Religious Coping and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 2292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, Avital, Yaira Raz-Hamama, Stephen Z. Levine, and Zahava Solomon. 2009. Posttraumatic Growth in Adolescence: The Role of Religiosity, Distress, and Forgiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 28: 862–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler-Row, Kathleen A., and Rachel L. Piferi. 2006. The Forgiving Personality: Describing a Life Well Lived? Personality and Individual Differences 41: 1009–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaskill, Ann. 2007. Exploring Religious Involvement, Forgiveness, Trust, and Cynicism. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 10: 203–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, John, Ann Macaskill, and Liza Day. 2001. Failure to Forgive Self and Others: A Replication and Extension of the Relationship between Forgiveness, Personality, Social Desirability and General Health. Personality and Individual Differences 30: 881–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, Barna Konkol Thege, and Michael F. Steger. 2010. It’s Not Only What You Hold, It’s How You Hold It: Dimensions of Religiosity and Meaning in Life. Personality and Individual Differences 49: 863–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., C. Garth Bellah, Shelley Dean Kilpatrick, and Judith L. Johnson. 2001. Vengefulness: Relationships with Forgiveness, Rumination, Well-Being, and the Big Five. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27: 601–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., Giacomo Bono, and Lindsey M. Root. 2007. Rumination, Emotion, and Forgiveness: Three Longitudinal Studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., K. Chris Rachal, Steven J. Sandage, Everett L. Worthington, Jr., Susan Wade Brown, and Terry L. Hight. 1998. Interpersonal Forgiving in Close Relationships: II. Theoretical Elaboration and Measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75: 1586–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., and Everett L. Worthington, Jr. 1999. Religion and the forgiving personality. Journal of Personality 67: 1141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, Susan H. 2013. Old persons, old age, aging, and religion. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York and London: Guilford Publications, pp. 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- Morano, Carmen L., and Denise King. 2005. Religiosity as a Mediator of Caregiver Weil-Being: Does Ethnicity Make a Difference? Journal of Gerontological Social Work 45: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, Maeve B., Christof N. Bentele, Hannah B. Grossman, Yunying Le, Hoon Jang, and Michael F. Steger. 2014. You, Me, and Meaning: An Integrative Review of Connections between Relationships and Meaning in Life. Journal of Psychology in Africa 24: 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2005. Religion as a Meaning-Making Framework in Coping with Life Stress. Journal of Social Issues 61: 707–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2013. Religion and Meaning. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 357–79. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Christopher, and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2004. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rye, Mark S., Kenneth I. Pargament, M. Amir Ali, Guy L. Beck, Elliot N. Dorff, Charles Hallisey, Vasudha Narayanan, and James G. Williams. 2000. Religious Perspectives on Forgiveness. In Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by Michael E. McCullough, Kenneth I. Pargament and Carl E. Thoresen. New York: Guilford, pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, Michael F. 2009. Meaning in Life. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Edited by Shane J. Lopez and Charles R. Snyder. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 679–87. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, Michael F., Patricia Frazier, Shigehiro Oishi, and Matthew Kaler. 2006. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53: 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., Todd B. Kashdan, Brandon A. Sullivan, and Danielle Lorentz. 2008. Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality 76: 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Laura Yamhure, Charles R. Snyder, Lesa Hoffman, Scott T. Michael, Heather N. Rasmussen, Laura S. Billings, Laura Heinze, Jason E. Neufeld, Hal S. Shorey, Jessica C. Roberts, and et al. 2005. Dispositional Forgiveness of Self, Others, and Situations. Journal of Personality 73: 313–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornstam, Lars. 2005. Gerotranscendence: A Developmental Theory of Positive Aging. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, Loren L., Ani Kalayjian, and Daria Diakonova-Curtis. 2017. Forgiveness Makes Sense: Forgiving Others Enhances the Salutary Associations of Meaning-Making with Traumatic Stress Symptoms. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 23: 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren L., Everett L. Worthington, Jr., and David R. Williams. 2015. Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, Cydney J., and Maurice J. Elias. 2007. How Forgiveness, Purpose, and Religiosity Are Related to the Mental Health and Well-Being of Youth: A Review of the Literature. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 10: 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tongeren, Daryl R., Jeffrey D. Green, Joshua N. Hook, Don E. Davis, Jody L. Davis, and Marciana Ramos. 2015. Forgiveness Increases Meaning in Life. Social Psychological and Personality Science 6: 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvliet, Charlotte van Oyen, Scott R. Hinze, and Everett L. Worthington. 2008. Unresolved Injustice: Christian Religious Commitment, Forgiveness, Revenge, and Cardiovas- Cular Responding. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 27: 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr. 2005. Handbook of Forgiveness. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2019. Predictors and Mediating Role of Forgiveness in the Relationship between Religious Struggle and Mental Health. Polskie Forum Psychologiczne 24: 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Beata, Rafał P. Bartczuk, and Radosław Rybarski. 2020. Centrality of Religiosity Scale in Polish Research: A Curvilinear Mechanism that Explains the Categories of Centrality of Religiosity. Religions 11: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Revenge motivation | 1.92 | 0.77 | − | |||||

| 2. Avoidance motivation | 3.17 | 0.74 | 0.28 *** | ‒ | ||||

| 3. Benevolence motivation | 3.22 | 0.72 | −0.44 *** | −0.51 *** | ‒ | |||

| 4. Presence of meaning | 5.34 | 0.96 | −0.39 *** | −0.24 *** | 0.26 *** | ‒ | ||

| 5. Search for meaning | 4.34 | 1.19 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.01 | ‒ | |

| 6. Religious meaning system | 5.25 | 1.03 | −0.55 *** | −0.34 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.19 ** | ‒ |

| Variables | Effect | SE | [LLCI, ULCI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effects | |||

| RM-RMS-PM | −0.35 | 0.05 | [−0.47, −0.26] |

| AM-RMS-PM | −0.24 | 0.04 | [−0.34, −0.15] |

| BM-RMS-PM | 0.40 | 0.06 | [0.28, 0.53] |

| RM-RMS-SM | −0.28 | 0.08 | [−0.46, −0.14] |

| AM-RMS-SM | −0.11 | 0.05 | [−0.22, −0.03] |

| BM-RMS-SM | 0.13 | 0.07 | [0.01, 0.29] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krok, D.; Zarzycka, B. Interpersonal Forgiveness and Meaning in Life in Older Adults: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of the Religious Meaning System. Religions 2021, 12, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010037

Krok D, Zarzycka B. Interpersonal Forgiveness and Meaning in Life in Older Adults: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of the Religious Meaning System. Religions. 2021; 12(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrok, Dariusz, and Beata Zarzycka. 2021. "Interpersonal Forgiveness and Meaning in Life in Older Adults: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of the Religious Meaning System" Religions 12, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010037

APA StyleKrok, D., & Zarzycka, B. (2021). Interpersonal Forgiveness and Meaning in Life in Older Adults: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of the Religious Meaning System. Religions, 12(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010037