Abstract

Material evidence from late medieval China attests that Buddhist of the Wuyue kingdom and Liao empire participated in the pan-Buddhist practice of dhāraṇīs and, more specifically, the cult of textual relics. What formed the basis of the cult is the Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Precious Casket Seal of the Concealed Complete-body Relics of the Essence of All Tathāgatas. I argue that the rhetoric of completeness, which is brought to the fore in the sutra’s title and reiterated throughout the text, lay at the heart of the success that it achieved. I trace the transfer of the text from South Asia to East Asia along the maritime routes, while closely examining designs and material forms, and various structuring contexts of the text. By doing so, I contribute to the scholarship on the cult of dhāraṇīs as relics of the dharma across Buddhist Asia.

1. Introduction

The Sanskrit term dhāraṇī—derived from a verbal root meaning to hold, to support, to maintain—refers to mnemonic devices, spells, and incantations.1 The dhāraṇīs are usually embedded in short Buddhist scriptures that center on instructions for their enactment and descriptions of their religious efficacies. The dhāraṇī scriptures became so numerous, in fact, that the need arose to classify them as a category of their own in the Buddhist canon, as exemplified by the term dhāraṇī piṭaka or “canon of spells” (tuoluoni zang 陀羅尼藏).2 Given the plethora of dhāraṇīs in the Buddhist tradition, it is odd that only a handful have been found, deposited within Buddhist stūpas or inscribed onto Buddhist images.3 The selection of the dhāraṇīs appears to have been guided by their function, meaning, and religious efficacies as stipulated in the texts that frame them within each sutra. This group of sutras promulgates that their dhāraṇīs are equivalent to the bodily relics of the Buddha when enshrined within stūpas and empower Buddhist statues when enshrined within or inscribed onto them.4

Material evidence from late medieval China attests that Buddhist of the Wuyue 吳越 (907–978) kingdom and Liao 遼 (916–1125) empire participated in the pan-Buddhist practice of dhāraṇīs and, more specifically, the cult of textual relics. What formed the basis of the cult in tenth-century China and beyond is the Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Precious Casket Seal of the Concealed Complete-Body Relics of the Essence of All Tathāgatas (Yiqie rulai xin mimi quanshen sheli baoqieyin tuoluoni jing 一切如來心祕密全身舍利寶篋印陀羅尼經; Skt. *Sarvatathāgatādhiṣṭhānahṛdayaguhyadhātukaraṇḍamudrā-nāma-dhāraṇī-mahāyānasūtra).5 Previous studies have examined its uses and meaning in a historical trajectory of dhāraṇī practices and the cult of textual relics in the Wuyue kingdom (Shi 2013, 2014). However, various aspects of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra remain unexplored, and major questions regarding its transmission and reception across East Asia still need to be answered. As Gregory Schopen’s groundbreaking study has shown, the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī was widely circulated and practiced in the context of relic cults in medieval South Asia. After the tenth century, it enjoyed unparalleled popularity in China, Korea, and Japan.6 The eastward transmission of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and its assimilation into local Buddhist cultures have been the subject of Baba Norihisa’s comprehensive study, for one.7 However, past scholarship has only haltingly suggested what made this text, among a group of dhāraṇī sutras that promise similar benefits, so appealing to the Buddhists from Abhayagiri to Chang’an 長安 and from Hangzhou 杭州 to Kaesŏng 開城and to Heiankyō 平安京 (present-day Kyoto 京都). I argue that the rhetoric of completeness, which is brought to the fore in its title and reiterated throughout the text, lay at the heart of the success that the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra achieved throughout medieval maritime Asia (Figure 1).8

Figure 1.

Major sites in the transfer and practice of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī, eighth–twelfth century.

Other aspects that have received scant attention are the visual and material dimensions of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra from late medieval East Asia. One of the important discoveries borne of recent research on dhāraṇīs is that their nature, function, and meaning are contingent on specific spatial and ritual contexts, which often were intertwined (Copp 2014). Dhāraṇīs in various visual formats and structuring contexts provide pathways to the ritual and devotional world of medieval East Asian Buddhists. I thus focus on how material embodiments of the dhāraṇī were enshrined in the Chinese context and in what ways that enshrinement is comparable to or distinct from practices in other regions. By closely examining designs and material forms, and various structuring contexts of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī in late medieval China, I will reveal key aspects of Buddhist art and visual culture that have long remained obscure.9

In what follows, I first lay out some key themes of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra to explain why this text was received so well by Buddhists throughout medieval maritime Asia. The sutra’s conceptualizations of the Buddha’s body attest to the far-reaching popularity of this dhāraṇī throughout the medieval Buddhist world. From there, I trace the transfer of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra from the southern Indic regions to East Asia along the maritime routes to the Wuyue kingdom. By doing so, I will contribute to the scholarship on the cult of dhāraṇīs as relics of the dharma across Buddhist Asia, and shed new light on the multifaceted material and visual role of dhāraṇīs in late medieval China.

2. The Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and the Rhetoric of Completeness

The Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra has been represented well in East Asia since the tenth century, although Chinese translation of the text had already appeared in the eighth century. Three Chinese translations of the dhāraṇī sutra are preserved in the Taishō canon: two are attributed to Amoghavajra (Bukong jin’gang 不空金剛, 704–774) and one to Dānapāla (Shihu 施護, ?–1017).10 The Sanskrit text of the sutra as a whole appears to have been lost, but that of the dhāraṇī, though it postdates Amoghavajra’s translation, has survived in inscriptions from Sri Lanka and present-day Odisha (formerly ‘Orissa’) on India’s eastern seabed. In Chinese translations of the sutra, the dhāraṇī appears toward the end, after a narrative frame explaining the occasion and purpose of its utterance by the Buddha.11

The sutra relates that, while the Buddha Śākyamuni was residing in Magadha (present-day Bihar) in eastern India, he was invited to the home of a Brahmin for offerings. On his way there, the Buddha was passing a garden when he noticed the ruins of an ancient stūpa within it. As he approached, a brilliant light issued from the earth with a voice of praise. The Buddha walked around the stūpa three times, removing his outer garment and placing it on the ruins. He wept, then smiled. Vajrapāṇi asked why. The dilapidated stūpa, the Buddha explained—since it held innumerable imprinted dharma essentials of the mind-dhāraṇī of all tathāgatas—contained the “complete-body relics” (quanshen sheli 全身舍利) of all tathāgatas.12 Then the Buddha explained the benefits and practices of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī, one of the said dharma essentials that had been deposited inside the ruined stūpa. The Buddha further stated: if one makes a copy of this sutra and places it inside a stūpa, that stūpa becomes an adamantine storehouse of the relics of all tathāgatas; and if one places the sutra inside an image of the Buddha, the image becomes as though it were made of the seven treasures.13 Anyone who worships such a stūpa or image, according to the sutra, attains non-retrogression, liberation from rebirths in the hells, and sundry other benefits.14 At Vajrapāṇi’s request, the Buddha recited the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī, and then the assembly headed toward the Brahmin’s house.15

As implied by its full title, the sutra equates its dhāraṇī and the complete-body relics of all tathāgatas. The said power of the dhāraṇī, according to the sutra, is actualized by the very act of enshrinement within a stūpa or image. To put it differently, a stūpa or image is empowered by the enshrinement of a dhāraṇī inscription just as if it were holding a bodily relic of the Buddha.16 Once the sounds of dhāraṇīs are transcribed onto material objects, dhāraṇīs become texts; once the texts are enshrined in stūpas, they become relics. For this reason, the cult of dhāraṇī has often been linked to the Buddhist cult of the stūpa and the “relic of the dharma” (fa sheli 法舍利), a notion that appears to have been formulated in close association with the “verse of dependent arising” or pratītyāsamutpādagāthā (yuanqi fa song 縁起法頌). On the one hand, the principle of dependent arising is at the heart of Śākyamuni Buddha’s teachings and, thus, was upheld as a fundamental text of the canon by almost every school (Boucher 1991, pp. 5–14). The pratītyāsamutpādagāthā occurs initially in the conversion of Sariputta and Moggallāna to Buddhism in the Mahāvāgga, an episode not directly associated with the worship of relics or stūpas. However, it became the first among the short texts or formulas to be considered as equivalent to a bodily relic of the Buddha for its capacity to make the departed Buddha present on earth through acts of inscription and installation.17

On the other hand, in the Chinese context, the famous pilgrim and monk Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664) identified, though implicitly, pratītyāsamutpādagāthā with the “relic of the dharma” in his eyewitness account of the Indian practice.18 Kuiji 窺基 (632–682), Xuanzang’s most renowned disciple, even equated it with a “relic of the dharma-body” (fashen sheli 法身舍利) although pratītyāsamutpādagāthā itself does not contain a self-identification with the relics of the Buddha or make use of the theory of the “three bodies” (sanshen 三身; Skt. trikāya) of the Buddha.19 As the doctrine of multiple Buddha-bodies was fully developed, the dharma body came to be understood as the basis of all other bodies of the Buddha in response to the needs of living beings. The use of these terms to classify and understand relics is also apparent in short sutras prescribing the installation of pratītyāsamutpādagāthā in stūpas or images that were translated into Chinese slightly after Xuanzang’s return to China. These include Sūtra Preached by the Buddha on the Merit of Constructing Stūpas (Foshuo zaota gongde jing 佛說造塔功德經), translated in 680, and Sūtra on the Merit of Bathing the Buddha (Yufo gongde jing 浴佛功德經), translated by Yijing 義淨 (635–713) in 710. The former explains that a text of the four-line verse, which stands for the totality of the teaching, is deposited in a stūpa because it represents the dharma body of the Buddha.20 The latter, considered as Yijing’s apocryphal work, equates the worship of the three bodies to that of the “relic of the dharma verse” (fasong sheli 法頌舍利).21 Such a move to apply the theory of Buddha’s bodies to relics appears to have been a later, if not Chinese, development in the historical understanding of pratītyāsamutpādagāthā.

By comparison, the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra belongs to an identifiable group of dhāraṇī sutras, instructing the practitioner to place their dhāraṇīs inside stūpas or images (Schopen [1982] 2005b, pp. 310–11), and resorts to a different line of thinking that was developed around the Buddha’s body and relics. Notably, this practice does not appear in early dhāraṇī sutras but seems to have emerged in the dhāraṇī sutras that were translated into Chinese around the turn of the eighth century (Copp 2014, pp. 35n27, 37). These include Sūtra of the Great Dhāraṇī on Stainless Pure Light (Wugou jingguang da tuoluoni jing 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經) and Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī for Ornamenting the Bodhi Site (Putichang zhuangyan tuoluoni jing 菩提場莊嚴陀羅尼經).22 A similar idea is reiterated in Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī of the Stainless Buddha-Coronaʼs Emitted Light Beaming through Ubiquitous Portals Contemplated as the Essence of the Tathāgatas (Foding fang wugou guangming ru pumen guancha yiqie rulai xin tuoluoni jing 佛頂放無垢光明入普門觀察一切如來心陀羅尼經), translated into Chinese in the tenth century. These dhāraṇī sutras are conventionally grouped with texts on pratītyāsamutpādagāthā under the rubric of “textual relics” in modern scholarship for several reasons. Both are short texts that encapsulate the essence of Buddha’s words, and are found, sometimes even together, in the spatial context of stūpas. However, this group of dhāraṇī sutras, the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in particular, shows several aspects that distinguish them from the tradition developed around pratītyāsamutpādagāthā. Given the surge of dhāraṇī sutras and the well-established status of the pratītyāsamutpādagāthā in middle period India, the rhetoric we find in this small group of dhāraṇī sutras may be understood as a way of promoting their dhāraṇīs in a highly competitive textual environment.23

Firstly, the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra identifies its dhāraṇī with the complete-body relics of all tathāgatas, going beyond the claim that its dhāraṇī is functionally equivalent to the bodily relic of the historical Buddha. The claim may seem absurd, considering that relics correspond to what were left behind after the body had decayed, disintegrated, or been cremated (Schopen 1998, p. 257). The dispersal of Buddha’s body was a prerequisite for obtaining relics for the benefits of sentient beings in his absence (Strong 2007). In this sense, the complete-body relics were premised upon the other part of the dyad—the “broken-body relics” (suishen sheli 碎身舍利)—even though it appears nowhere in the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra.24 The use of such prefixes seems to have been one way of bringing out a particular characteristic of the ambiguous object called śarīra (sheli 舍利), which can refer to the entire body or a minute part of it (Fontein 1995, p. 21). The term “complete-body relics” had already appeared in such influential texts as the Lotus Sūtra (Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮華經),25 whereas the opposition between the complete-body relics and the broken-body relics had been introduced in Vast Sūtra on the Descent of the Bodhisattvaʼs Consciousness from the Tuṣita Heaven into His Motherʼs Womb (Pusa cong Doushoutian jiang shenmutai shuo guangpu jing 菩薩從兜術天降神母胎說廣普經) prior to the advent of dhāraṇī sutras.26 The dyad is also glossed in Chinese Buddhist encyclopedias such as Various Aspects of Sutras and Vinayas (Jinglü yixiang 經律異相) or A Forest of Pearls from the Dharma Garden (Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林).27 In these texts, the term “complete-body relics” refers to the body of certain Buddhas of the past who could appear in their integral bodies even after entering nirvana.28 Intriguingly, the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra appears to have been connected to this earlier tradition of undispersed bodies of past Buddhas rather than the concurrent literature on the pratītyāsamutpādagāthā in asserting the integrity of its dhāraṇī.29 The passage “complete-body relics of all tathāgatas,” reiterated throughout the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra, would have reminded readers (and practitioners) of the fragmentary nature of the Buddha’s bodily relics.30 The Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī for Ornamenting the Bodhi Site, another text whose translation is attributed to Amoghavajra, similarly claims the supremacy of its main dhāraṇī over “relics divided from the body” (shen fun sheli 身分舍利) of the Buddha, an expression that immediately recalls the fragmentary nature of corporeal relics.31

Secondly, the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra presents a practice of infinitely inclusive and self-duplicative nature. Copying a dhāraṇī and enshrining it in a stūpa creates the complete-body relics of an unimaginably large number of tathāgatas and, by extension, the aggregated power of them all.32 The sutra asserts that “This is because the complete-body relics of all tathāgatas of future, present, and those who have already entered parinirvāṇa all exist in the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī. The entirety of the three bodies of all tathāgatas is also present in it.”33 This sutra passage takes religious efficacies of a rather simple practice to a cosmic level beyond temporal boundaries. In particular, the sutra makes a move to subsume the pre-established cult of pratītyāsamutpādagāthā, which had been equated with one of the three bodies, under the cult of its dhāraṇī by this audacious claim of having “the entirety of the three bodies of all tathāgatas.” It is worth noting that this passage was cited in an inscription, entitled “Instructions for Enshrining Relics of the Dharma inside Buddha Images” (Fo xingxiang zhong anzhi fa sheli ji 佛形像中安置法舍利記) excavated from the upper relic crypt of a Liao pagoda in present-day Bairin Right Banner, Inner Mongolia.34

The temporal expandability of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī resonates with the spatial pervasiveness of the Bodhi Dhāraṇī or the main spell of the Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī for Ornamenting the Bodhi Site. The sutra asserts that if one installs an inscription of the Bodhi Dhāraṇī and its sutra in a stūpa, the whole universe becomes filled with relics of the dharma-body, relics of the dharma-realm (fajie sheli 法界舍利), relics of bone (gu sheli 骨舍利), and relics of flesh (rou sheli 肉舍利).35 Thus, the establishment of such a stūpa equals that of innumerable stūpas as well as that of a stūpa containing relics of all tathāgatas.36 In a related vein, this group of dhāraṇī sutras commonly speaks of amplifying the merit generated by the establishment and worship of a stūpa by depositing such dhāraṇīs inside. Oftentimes, the merit derived from the act of constructing such a stūpa is equated to that of constructing innumerable stūpas. This feature was held in high regard, to the extent of being incised together with the Bodhi Dhāraṇī onto a stone slab found long ago in Odisha.37

The use of this group of dhāraṇīs throughout South Asia in the medieval period shows their great appeal to Buddhist devotees. Confirming the uses prescribed in the sutras, these dhāraṇīs are frequently found in the remains of stūpas or monastic compounds in eastern India and Sri Lanka, as we will examine shortly. With the transfer and translation of this group of dhāraṇī sutras, the idea of replacing bodily relics with condensed, printed texts achieved great popularity in Korea and Japan from the eighth century onward.

3. Transfer of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra across Medieval Maritime Asia

The Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra was among translations of seventy-seven titles in 101 fascicles that Amoghavajra presented to the throne on the occasion of Emperor Daizong’s 代宗 (r. 762–779) birthday, 22 November, 771.38 The translated texts not only represent the textual corpus of Amoghavajra, a prolific translator second to Xuanzang in the history of Chinese Buddhism, but also provide a glimpse of “important new Buddhist developments in South Asia,” where the source texts of Amoghavajra’s translations were formulated and practiced (Orzech 2011, pp. 263–65). The Continued Catalog of Śākyamuni’s Teachings from the Kaiyuan Period Compiled in the Zhenyuan Reign Period of Great Tang (Da Tang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan shijiao lu 大唐貞元續開元釋敎錄) reveals that the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra, along with other texts, became part of the Chinese Buddhist canon in 772.39

Amoghavajra’s textual acquisitions seem to have been achieved during his journey to the southern Indic kingdoms. Extant biographical sources of Amoghavajra concur that he went to Sri Lanka but diverge on the question of whether Amoghavajra made his way to India.40 His sojourns in Sri Lanka are recorded in a funerary epitaph composed in 774 by his disciple Feixi 飛錫 (fl. 742–805). Shortly after the passing of his teacher in 741, Amoghavajra traveled by sea to the southern Indic kingdoms as the emperor’s official envoy. While staying in Sri Lanka, Amoghavajra is said to have heard of a sage called ācārya Samantabhadra (Puxian asheli 普賢阿遮梨) who had settled in a sacred site nearby. The ācārya Samantabhadra, upon receiving gold and jewels as a pledge of offering, gave Amoghavajra the Eighteen Assemblies of the Diamond Pinnacle Yoga (Shiba hui Jingangding yuqie 十八會金剛頂瑜伽), the Vairocana’s Great Compassion Wombstore (Piluzhena Dabei taizang 毘盧遮那大悲胎藏), the “mantra of the five divisions of initiation” (wubu guanding zhenyan 五部灌頂眞言), and the “scriptures and commentaries of the secret canon” (midian jinglun 秘典經論), contained in “some five hundred palm-leaf manuscripts” (fanjia wubai yu bu 梵夾五百餘部). He returned to China some five years later.41

Dhāraṇī sutras are not explicitly mentioned in Feixi’s list of Amoghavajra’s textual acquisitions, but they comprise a considerable portion of the translated texts that Amoghavajra submitted to the throne in 772.42 It is no coincidence that some of the dhāraṇīs that Amoghavajra introduced to China have been found inscribed both in Sri Lanka, where Amoghavajra acquired a cache of Indic texts, and in eastern India, in Buddhist sites of Odisha. These inscriptions suggest that frequent interactions took place between monasteries in eastern India, where Mahāyāna and Tantric Buddhism flourished under the patronage of Pāla (750–1120) rulers, and Abhayagiri Vihāra—a center of Mahāyāna and Tantric Buddhism in Anurādhapura, Sri Lanka until the twelfth century. The two locales, closely linked by sea routes—along which ideas, texts, images, and associated practices traveled—have yielded evidence of the widespread use of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī to consecrate stūpas and images. Thus, it is pertinent to consider written traces of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī in South Asia though they postdate Amoghavajra’s reception and translation of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra. Some of these texts, as indicated by the mention of “five hundred palm-leaf manuscripts” in the account of Amoghavajra’s textual acquisition, may have been transmitted from India to Sri Lanka, and from there to China in manuscript form.

Eight granite tablets found buried near the Northern Dagoba at the site of Abhayagiri Vihāra are highly important in this regard (Mudiyanse 1967, pp. 99–105). Gregory Schopen has interpreted the Sanskrit texts on six of the eight tablets (nos. I, II, III, IV, VI, and VIII) as parts of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī,43 while Rangama Chandawimala has identified the two remaining dhāraṇīs (nos. VI and VII) as parts of the Vajra-guhya-vajramandala-vidhi-vistara in chapter two of the Sarvatathāgata-tattvasaṃgraha Sūtra (hereafter STTS) (Chandawimala 2013, pp. 128–50). The identification of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī and the dhāraṇī quoted from the STTS on the Abhayagiri tablets reveals the heterogeneous nature of the Buddhist thought and practices prevalent at Abhayagiri Vihāra as late as the ninth century (Baba 2017, p. 124). The concurrence of dhāraṇīs culled from Mahāyāna and Tantric texts at the site becomes even more intriguing when we consider that Amoghavajra is said to have acquired the teaching of the Eighteen Assemblies of the Diamond Pinnacle Yoga under the tutelage of the ācārya Samantabhadra in Sri Lanka.

The literary and epigraphic evidence examined above has led Baba Norihisa to conclude that Amoghavajra obtained the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in Sri Lanka instead of India and took it to China. He goes as far as to suggest that Amoghavajra may have acquired the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra from the Abhayagiri Vihāra (Baba 2017, pp. 125–26). Given Amoghavajra’s interest in the Tantric texts, he may have frequented the monastery during his stay on the island. That the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī on the Abhayagiri tablets is almost identical to its Chinese translation by Amoghavajra supports this proposition.44 The findspot of the dhāraṇī stones at Abhayagiri once again underscores the role of Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī in the consecration and worship of stūpas. Although the epigraphic evidence at our disposal is not enough to complete a picture of the transmission of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī from India to Sri Lanka, contemporaneous dhāraṇī inscriptions demonstrate increasing use of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī and similar ones for the consecration of stūpas and images. These dhāraṇīs were used either independently or in groups. Perhaps the most impressive examples are inscriptions of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī on two stone slabs from the site of Udayagiri II. Archaeologists have surmised that the slabs were initially deposited in a stūpa or caitya although they had already been lost due to dilapidation and the enlargement of structures at the site (Trivedi 2011, p. 217). Sanskrit inscriptions Nos. 8 and 27, dated to circa the ninth to the tenth, and the tenth to eleventh centuries, respectively, on paleographic grounds, show an identical combination of dhāraṇīs.45 Tanaka Kimiaki identifies the two inscriptions and discusses the implications as follows.46 They contain the pratītyāsamutpādagāthā, the mūlamantra, hṛdaya, and upahṛdaya from the Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī for Ornamenting the Bodhi Site,47 the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī,48 and the Vimaloṣṇīṣa Dhāraṇī (Foding wugou pumen sanshi rulai xin tuoluoni 佛頂無垢普門三世如來心陀羅尼).49 A similar yet simpler combination of dhāraṇīs was found on the back slab of the Jaṭāmukuṭa Lokeśvara image excavated near the shrine complex of Udayagiri I. The inscription contains the Vimaloṣṇīṣa Dhāraṇī, the pratītyāsamutpādagāthā, and the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī.50 Another example of a similar sort was found buried in the mound on which the village of Kurkihār now sits in present-day Bihar. A bronze frame bears an inscription of the pratītyāsamutpādagāthā, followed by the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī (Revire 2016, pp. 239–48).

Archaeological finds from Sri Lanka and East India, though they postdate Amoghavajra’s translation of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra, still demonstrate the prevailing practice of inscribing a clearly identifiable group of dhāraṇīs inside stūpas or onto the surface of Buddhist images. They further suggest that such a practice was transferred eastward along with the movement of Buddhist monks, who crossed the seas and acted as cultural agents. A note should be made here regarding the status of these dhāraṇī inscriptions at major cultic sites of East India. They were mostly found within or upon smaller stūpas of a devotional nature surrounding the main stūpa that had been erected for the bodily relics of the Buddha at given monastic compounds (Mishra 2016, pp. 81–82). The subsidiary position of the stūpas or tablets on which these inscriptions appeared cautions us not to argue for the equal significance of the textual and bodily relics of the Buddha too generally. It further indicates that the selected dhāraṇīs were meant to consecrate smaller stūpas for the generation of merit on the part of devotees. These two features are reiterated in the cult of Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in East Asia, as we will examine shortly.

Given that most of the dhāraṇīs or pratītyāsamutpādagāthā were introduced to Chinese Buddhists by the seventh and eighth centuries, it comes as a surprise that their written traces have rarely been found in relic deposits of Chinese pagodas predating the tenth century.51 Many of the extant Chinese dhāraṇī inscriptions from the eighth to the tenth centuries have been unearthed in the funerary context, pointing to a function different from substitute relics of the Buddha.52 It is, furthermore, enigmatic, considering that the neighboring kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula and the Japanese archipelago witnessed the development of the practice based on the Sūtra of the Great Dhāraṇī on Stainless Pure Light. In late-eighth-century Japan, for example, it seems to have resulted in the creation of one million miniature pagodas, each containing a copy of a woodblock-printed dhāraṇī. Empress Kōken’s 孝謙天皇 (r. 749–758) production and distribution of one million dhāraṇī-filled miniature pagodas were based on the prescription found in the Sūtra of the Great Dhāraṇī on Stainless Pure Light.53 However, it was not until the tenth through the eleventh centuries that some of these dhāraṇīs in various material forms entered the crypts of Chinese pagodas. On the one hand, the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī seems to have been the most prevalent in the southeast coastal region of China. On the other, several dhāraṇīs were sometimes used in conjunction with pratītyāsamutpādagāthā in the relic crypts of pagodas erected during the Liao. Material traces of pratītyāsamutpādagāthā from the Tang period have been mostly discovered in present-day Xi’an, where Chinese pilgrims, who recorded the practice associated with the verse or translated sutras prescribing its uses, were active in the late seventh and early eighth centuries. Considering the geographical distribution of the Tang examples, the resurgence of pratītyāsamutpādagāthā during the Liao period is highly intriguing. The archaeological evidence at our disposal, however, appears to indicate that the Tang Buddhist was not attracted to the practice of depositing dhāraṇī inscriptions as substitutes for, or together with, corporeal relics of the Buddha.54

For students of Tang Buddhist visual culture, this has been a conundrum, particularly given the number of such dhāraṇī sutras preserved in the Chinese Buddhist canon and the enormous popularity, around the turn of the eighth century, that some of the newly translated ones enjoyed in neighboring kingdoms. One hypothesis that has been proposed is that the sudden interest in the practice had something to do with Empress Wu Zetian 武則天 (r. 690–705) ordering the translation of the Sūtra of the Great Dhāraṇī on Stainless Pure Light into Chinese. She is said to have vowed to manufacture 8,040,000 precious relic pagodas filled with dhāraṇīs in emulation of the great Indian emperor Aśoka.55 However, her vow was not realized when she died in 705. The practice of depositing and venerating dhāraṇī inscriptions inside pagoda crypts seem to have lost momentum as the Tang imperial house turned almost exclusively to worship of the “true-body relic of the Buddha” (zhenshen sheli 眞身舍利) or the Buddha’s finger bone relic housed at Famen si 法門寺.56

Although evidence of the veneration of these dhāraṇīs is hard to find in pagoda crypts of the Tang dynasty, the dhāraṇīs appear to have been known and recited among the Tang Chinese. The Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī, for instance, is included in the Collection of the Secret Storehouse of Dhāraṇīs of the Highest Vehicle of Buddhism (Shijiao zuishang sheng mimi zang tuoluoni ji 釋教最上乘秘密藏陁羅尼集), which compiles spells that were circulated and practiced in the capital Chang’an up until the ninth century.57 The mūlamantra, hṛdaya, and upahṛdaya from the Sūtra of the Dhāraṇī for Ornamenting the Bodhi Site are also included in this comprehensive collection of dhāraṇīs.58 The circulation of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in the Sinitic Buddhist sphere is corroborated by lists of Buddhist texts obtained by Japanese monks in their travels to Tang. For example, Kukai 空海 (774–835) is said to have brought manuscripts of both the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and the Sanskrit dhāraṇī to the Japanese archipelago in 806.59 Ennin 圓仁 (794–864) and Enchin 圓珍 (814–891) are recorded to have brought a copy of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in Amoghavajra’s translation from China to Japan in 847 and 858, respectively.60 However, there is scant material and textual evidence from Japan that this text was used in a way comparable to the archaeological evidence from South Asia. Taken together, the lack of written traces of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and its dhāraṇī from East Asian pagodas before the tenth century presents pictures of its reception that are specific to China, Korea, and Japan.

4. The Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in Tenth-Century China

Although the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī was known among the Tang Chinese, it did not enjoy great popularity until the late tenth century. Comparison among extant Chinese recensions and xylograph copies from China and Korea has revealed that Amoghavajra’s phonetic transcription of the dhāraṇī was well-received in China, Korea, and Japan in the late medieval period (Hayashidera 2013). That Amoghavajra’s translation was circulated and put into practice in China, Korea, and Japan implies the transmission of so-called “esoteric” Buddhist texts first in the eighth century, and later from the tenth to the eleventh centuries. While the retranslation of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in the tenth century reflects the continued popularity of the dhāraṇī in the Indic Buddhist sphere, where Dānapāla hailed from, Dānapāla’s new translation under Northern Song imperial patronage did not find purchase in East Asia. This picture of reception points to the enduring popularity of Amoghavajra’s translation of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and the maritime networks which carried this version from China to Korea and from China to Japan.

Despite the circulation of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in the Sinitic Buddhist sphere during the Tang dynasty, the tremendous popularity and wide reach of the text after the tenth century are hard to separate from the state-sponsored printing under the royal patronage of Wuyue, an independent kingdom that prospered in the southeast coastal region of China amid the political turbulence of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Hangzhou, the kingdom’s capital, became a cultural center where Buddhist monks gathered and Buddhist monuments were constantly being built under royal patronage. The metropolis was closely connected to neighboring kingdoms in Korea and Japan through its main port, Mingzhou 明州 (present-day Ningbo 寧波). Royal patronage of Buddhism culminated during the reign of Wuyue’s last monarch, Qian Chu 錢俶 (r. 948–978; also known as Qian Hongchu 錢弘俶). Zhipan’s 志磐 (ca. 1220–1275) Complete Chronicle of the Buddha and Patriarchs (Fozu tongji 佛祖統紀, comp. 1269) relates that Qian Chu had produced 84,000 stūpas out of gilt-bronze and iron in admiration of the deeds of King Aśoka and had each enshrine a copy of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra. Stūpas containing sutras were distributed throughout his kingdom.61 This account calls to mind the famous legend of King Aśoka, who is said to have opened seven of the eight stūpas holding relics of the Buddha, distributed those relics, and built 84,000 new stūpas across his kingdom (Strong 2004, pp. 136–44).

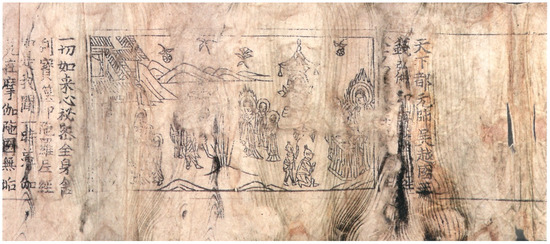

This Southern Song account has been validated, as more than twenty such miniature stūpas and copies of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in three xylograph editions have emerged from archaeological excavations in China since the 1950s. More than 40 examples of cast bronze and iron miniature stūpas, commissioned in 955 and 965, have survived in China and Japan.62 Additional textual and material evidence reveals several key aspects of Qian Chu’s relic campaign implemented in three stages from the 950s to the 970s. In 955, the monarch pledged to dedicate small bronze reliquaries in the form of a single-storied stūpa with idiosyncratic features not found in contemporaneous pagodas.63 The printing of 84,000 copies of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in 956, as stated in a colophon of two extant copies, was intended to supply relics for veneration inside precious stūpas.64 One example was found inside a stone pillar at the site of Tianning si 天寧寺 in Huzhou 湖州, Zhejiang Province in 1917 (Edgren 1972), whereas the other was discovered in a brick tomb beneath a Song-dynasty relic pagoda in Wuwei County, Anhui Province in 1971 and is now in the collection of Anhui Provincial Museum (Figure 2).65

Figure 2.

Detail of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra. Found in Wuwei County, Anhui Province, China. 956 CE, Wuyue (907–978). Xylograph; ink on paper. H. 7 cm; L. 150 cm. Anhui Provincial Museum. After (Li 2011, p. 156).

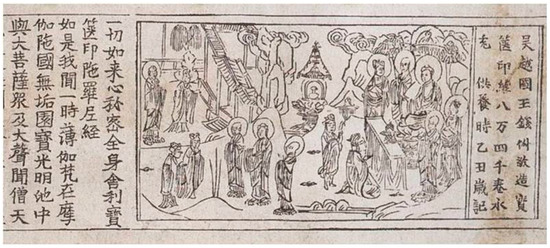

Sets composed of a relic and a reliquary are said to have been sent to Japan, a claim corroborated by some 10 such reliquaries that have survived in the archipelago. The Japanese monk Dōki 道喜 (fl. tenth century) left an eyewitness account, entitled “Account of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra” (Jp. Hōkyōin kyō ki 寶篋印經記), upon examining a set of a bronze miniature stūpa and a printed scroll of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in 965 (Ono 2008; Shen 2019, p. 199). Ten years later, Qian Chu produced some small iron reliquaries that were similarly configured and distributed them within his kingdom. A copy of this edition was found in a miniature iron stūpa excavated from the construction site in Shaoxing City, Zhejiang Province in 1971. When the set was found, the iron stūpa was reported to have held a red wooden cylindrical container with a xylograph scroll of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra (Figure 3).66

Figure 3.

Detail of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra. Found inside the miniature iron stūpa discovered in Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, China. 965 CE, Wuyue (907–978). Xylograph; ink on paper. H. 8.5 cm; L. 182.8 cm. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. After (Li 2009b, p. 13).

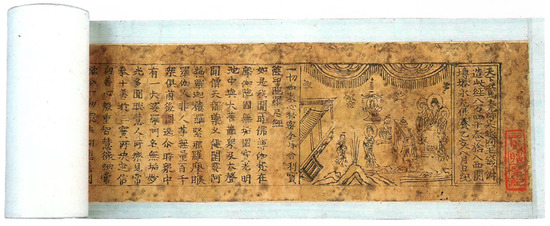

In 975, Qian Chu once again sponsored the printing of this sutra not for venerating within miniature metal stūpas but for the Leifengta 雷峰塔, a towering brick pagoda built from 972 to 976 on the banks of the West Lake in Hangzhou.67 When the Leifengta collapsed in 1924, numerous copies of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra were found in small holes in the bricks that made up the top level of the pagoda (Figure 4 and Figure 5).68

Figure 4.

A scroll of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra. 975 CE, Wuyue (907–978). Xylograph; ink on paper. H. 7.6 cm; L. 210 cm. Found in the ruins of the Leifengta, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. After (Li 2009b, p. 45).

Figure 5.

Hollowed brick that encased a printed scroll. Found in the ruins of the Leifengta, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. Ca. 975 CE, Wuyue (907–978). L. 37 cm; W. 18 cm; D. 6 cm. Zhejiang Provincial Museum. After (Li 2010, p. 132).

More than one thousand copies of these printed scrolls were reported to have been found in situ, but most had already decomposed (Huang 2011, pp. 137–38). Recent archaeological excavation of the ruins suggests that the two miniature stūpas, handcrafted with silver for the upper and underground relic crypts, held bodily relics of the Buddha (Zhejiangsheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo 2002, pp. 66–67). In sum, the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra was printed for miniature bronze stūpas in 956, for miniature iron stūpas in 965, and in 975 not for miniature silver stūpas, but for a monumental brick pagoda and for the precise purpose of being placed within them.

Qian Chu’s undertaking is one example of Chinese imperial attempts to reenact the legend of King Aśoka. Qian Chu’s relic campaign recalls the undertakings of Emperor Wen 文帝 (r. 581–604) of the Sui 隋 (581–618) or Empress Wu Zetian of the Tang. On three occasions, the Sui emperor had relics distributed and enshrined in newly built pagodas throughout the empire, whereas the Tang empress vowed to manufacture 8,040,000 precious relic pagodas filled with dhāraṇīs.69 Although Qian Chu was not a ruler of the empire, he was a “true king” (zhenwang 眞王), a hereditary title conferred upon the kings of Wuyue by the emperors of the Five Dynasties governing in central China.70 The superior position of the Wuyue kings over rulers of other kingdoms in the south may have justified Qian Chu’s emulation of the Aśokan legend. What is innovative about Qian Chu’s undertaking is the combination of elements that were developed along disparate lines in the earlier relic veneration. The combination of allusions to King Aśoka’s construction of 84,000 stūpas, the worship of miniature stūpas, and the printing of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra, as Baba Norihisa aptly points out, seem to have come together for the first time in Qian’s construction of miniature stūpas in the history of Chinese relic practices (Baba 2017, p. 130). First of all, instead of constructing monumental pagodas, Qian Chu opted to make sets of relics and reliquaries and distribute them within the Wuyue territory. He found a link to the Aśokan legend by selecting as the model for his miniature stūpas the “Aśoka Stūpa” of Ayuwang si 阿育王寺 in Maoxian 鄮縣 in present-day Ningbo, which had been revered as one of King Aśoka’s 84,000 stūpas.71 However, there is a crucial difference between the reliquaries distributed by King Aśoka and Qian Chu: the former contained bodily relics whereas the latter contained copies of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra. Although Zhipan wrote about Qian Chu’s practice as a matter of course in the account discussed above, it was unprecedented in the long history of Chinese relic veneration. Empress Wu, though she commissioned the translation of the Sūtra of the Great Dhāraṇī of the Stainless Pure Light, did not live to see her vow accomplished. The medium of woodblock printing seems to have been selected to serve the dual goals of achieving the said number of 84,000, one of the palpable links to the legendary deeds of the Indian monarch, and of ensuring the shared identity of produced relics and reliquaries. Although there is no way to assess whether the said quality was realized, woodblock printing technology, which became more sophisticated from the tenth century onward, provided a new means for reproducing Buddhist relics on unparalleled scale.

Two important questions that arise, then, are who advised the king to orchestrate the relic campaign and why the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra was selected from dhāraṇī sutras with similar contents that were available at the time. The Japanese monk Dōki, in his “Account of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra,” states that one of Qian Chu’s beloved monks is said to have advised the king to build stūpas and copy the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra (Shi 2014, p. 86n10). Several scholars posit that Yongming Yanshou 永明延壽 (904–975), an eminent Chan monk who served as Qian’s Buddhist advisor and was closely associated with monasteries in the Wuyue territory, was the mastermind behind Qian Chu’s relic campaign (Zhang 1978, p. 75; Baba 2017, pp. 130–32). According to Lingzhi Yuanzhao’s 靈芝元照 (1048–1116) Records of the Chan Monk Yongming Zhijue (Yongming Zhijue chanshi fangzhang shilu 永明智覺禪師方丈實錄), the monk “requested that the state constructs 84,000 iron stūpas” and solicited donations to construct 10,000 lacquer Aśoka stūpas (Yanagi 2015, p. 395 [9B]; Zhang 1978, p. 76). Furthermore, Yanshou is recorded to have commissioned 140,000 copies of the “Charts of Amitābha Stūpa” (Mituo ta tu 彌陀塔圖) for public distribution (Zhang 1978, p. 75). In a similar vein, Records of the Chan Monk Yongming Zhijue states that Yanshou engaged in the printing of sutras such as the Perfection of Wisdom and Lotus Sūtra (Yanagi 2015, p. 395 [9B]). Given Yanshou’s close connection to the monarch and his various practices involving mass production of Buddhist objects, Yanshou may have advised the king to carry out decades-long relic veneration.72 Still, one can only speculate as to why Yanshou chose the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra among others. One hypothesis posits that the phrase “the mind of all tathāgatas” (yiqie rulai xin一切如來心) may have appealed to Yanshou, who asserted that the “Mind is the Buddha itself” (jixin shi fo 即心是佛) in his thought.73

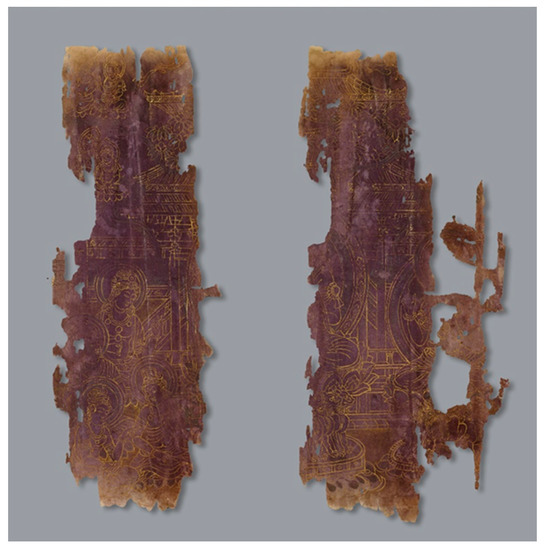

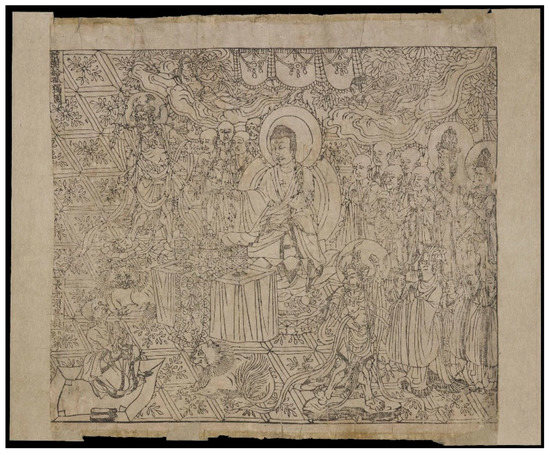

In the Wuyue materializations of the Buddha’s potent words, unlike comparable examples from India or Sri Lanka, the dhāraṇī sutra was reproduced in its entirety. At Abhayagiri and Odisha, the dhāraṇī was engraved on stone tablets without any framing narrative.74 The decision to reproduce the integral text had an impact on its visual and material dimensions. The three Wuyue editions of the dhāraṇī sutra were designed in a format fitting for folded paper scrolls that was developed in China. The printed scrolls open with a frontispiece, which is a square or elongated pictorial composition before the sutra that serves as a gateway to the sacred text as well as an embellishment for it.75 The frontispiece usually illustrates key scenes from the narrative of a sutra or a generic preaching scene in which the main protagonist, usually the Buddha, summons his followers. Manuscripts from East Asia suggest that this unique mode of illustration was already in practice by the mid-eighth century. A handscroll of the Flower Garland Sūtra from Korea, dated 754–755 CE, shows one of the earliest known frontispieces in East Asia (Figure 6), whereas a handscroll of the Diamond Sūtra from China dated 868 CE attests to the adoption of a well-established form in printed texts (Figure 7).76

Figure 6.

Frontispiece to the Flower Garland Sūtra. Ca. 754–755 CE, Silla (57 BCE–935). Gold and silver pigment on red mulberry paper. H. 25.7 cm; L. 10.9 cm; H. 24.0 cm; L. 9.3 cm. Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.

Figure 7.

Frontispiece to the Diamond Sūtra. Found in Cave 17 of Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China. 868 CE, Tang (618–907). Xylograph; ink on paper. H. 27.6; W: 28.5 cm. British Library.

However, it was not until the tenth century that this distinctive mode of illustration became more widely adopted due to the circulation of illuminated Buddhist texts in the Sinitic world. This is aptly attested by the Korean reception of one of the three Wuyue editions of the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra in the early Koryŏ 高麗 (918–1392) period.77

5. Conclusions

This article has presented a wide range of inscriptions citing the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī from different corners of medieval maritime Asia. I have attempted to contextualize the Chinese evidence, which comes in the middle of a long history of transfer and reception of this short yet significant scripture in East Asia. Textual and visual evidence from India, Sri Lanka, and China examined in this study suggests that the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra was primarily transferred along sea routes. It has demonstrated the rich cultural implications of this short scripture’s long journey throughout East Asia. It is now possible to take a more nuanced perspective on the place of Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and its dhāraṇī in the Buddhist veneration of text-cum-relics.

The Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra, as its full title implies, brings the notion of Buddha’s body, in terms of relics, to the fore. Its great appeal to medieval Buddhists seems to have stemmed from its ability to make all Buddha-bodies in the universe present in one stūpa. By taking the terms “complete-body relics” and “three bodies” in the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and their material referents into full consideration, this study has traced the origins and development of the discourses, practices, and understandings that shaped the construction of Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī as a particular type of Buddha’s bodies. The use of the body terminology appears to have been one way of promoting the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī among a group of texts that similarly present short dhāraṇīs and promise great merit to those who write them down and venerate the material representations inside the particular spatial contexts of stūpas/pagodas and the inner recesses of statues. On the one hand, the rhetoric of complete-body relics, so pervasive in the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra, alludes to far greater diversity and complexity in the conceptualizations of dhāraṇīs as Buddhist bodies and styles of dhāraṇī practice. On the other hand, it also appropriates the doctrinal understanding of the Buddha’s three bodies, a line of thinking that had appeared in China about 50–70 years prior in the cult of pratītyāsamutpādagāthā. All types of Buddha’s bodies are said to have been present in the “Precious Casket Seal,” and this is precisely what has made the sutra so popular in the Sinitic Buddhist sphere since the tenth century.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This article grew out of a chapter from my PhD dissertation. I am thankful to the members of my dissertation committee at the University of Chicago, Wu Hung, Paul Copp, and Aden Kumler, for their critical and perceptive comments on earlier incarnations of this article. Special thanks go to Haewon Kim and Peter Skilling for their constructive suggestions during different phases of my research. I also wish to thank Juhyung Rhi and Soonil Hwang for their generous help with my research. I am deeply grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and valuable comments. Needless to say, all errors that may remain are mine.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

T Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaikyoku 渡邊海旭 et al. Ed. 1924–1935. Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大蔵経. 85 vols. Tokyo: Taishō issaikyō kankōkai.

F Zhongguo fojiao xiehui 中国佛教协会 and Zhongguo fojiao tushu wenwuguan 中国佛教图书文物馆, ed. 2001. Fangshan shijing 房山石經. 30 vols. Beijing: Huaxia chubanshe.

References

Primary Sources

Chishō daishi goshōrai mokuroku 智證大師請來目録, T 55, no. 2173.Da Tang gu dade zeng sikong dabian zhengguangzhi Bukong sanzang xingzhuang 大唐故大徳贈司空大辨正廣智不空三藏行状, T 50, no. 2056.Da Tang xiyu ji 大唐西域記, T 51, no. 2087.Da Tang Zhenyuan xu Kaiyuan shijiao lu 大唐貞元續開元釋敎錄, T 55, no. 2156.Daizong zhaozeng sikong dabian zhengguangzhi sanzang heshang biaozhi ji 代宗朝贈司空大辯正廣智三藏和上表制集, T 52, no. 2120.Dasheng liqu liu boluomida jing 大乘理趣六波羅蜜多經, T 8, no. 261.Fayuan zhulin 法苑珠林, T 53, no. 2122.Foding fang wugou guangming ru pumen guancha yiqie rulai xin tuoluoni jing 佛頂放無垢光明入普門觀察一切如來心陀羅尼經, T 19, no. 1025.Foshuo zaota gongde jing 佛說造塔功德經, T 16, no. 699.Fozu tongji 佛祖統紀, T 49, no. 2035.Goshōrai mokuroku 御請來目録, T 55, no. 2161.Jinglü yixiang 經律異相, T 53, no. 2121.Nanhai jigui neifa zhuan 南海寄歸内法傳, T 54, no. 2125.Nittō shingu shōgyō mokuroku 入唐新求聖教目録, T 55, no. 2167.Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮華經, T 9, no. 262.Miaofa lianhua jing xuanzan 妙法蓮華經玄賛, T 34, no. 1723.Shijiao zuishang sheng mimi zang tuoluoni ji 釋教最上乘秘密藏陁羅尼集, F 28, no. 1071.Pusa cong Doushoutian jiang shenmutai shuo guangpu jing 菩薩從兜術天降神母胎說廣普經, T 12, no. 384.Putichang zhuangyan tuoluoni jing 菩提場莊嚴陀羅尼經, T 19, no. 1008.Yiqie rulai xin mimi quanshen sheli baoqieyin tuoluoni jing 一切如來心祕密全身舍利寶篋印陀羅尼經, T 19, no. 1022A.Yiqie rulai xin mimi quanshen sheli baoqieyin tuoluoni jing 一切如來心祕密全身舍利寶篋印陀羅尼經, T 19, no. 1022B.Yiqie rulai zhengfa mimi qieyin xin tuoluoni jing 一切如來正法祕密篋印心陀羅尼經, T 19, no. 1023.Yufo gongde jing 浴佛功德經, T 16, no. 698.Secondary Sources

- Acri, Andrea. 2016. Introduction: Esoteric Buddhist Networks along the Maritime Silk Routes. In Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia: Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons. Edited by Andrea Acri. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, Norihisa (馬場紀寿). 2012. Hōkyōin kyō no denpa to tenkai: Suri ranka no daijō to Fukū, Enju, Chōgen, Keihan (『寶篋印經』の傳播と展開: スリランカの大乘と不空、延壽、重源、慶派). Bukkyōgaku (仏教学) 54: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, Norihisa. 2017. From Sri Lanka to East Asia: A Short History of a Buddhist Scripture. In The “Global” and the “Local” in Early Modern and Modern East Asia. Edited by Benjamin A. Elman and Chao-Hui Jenny Liu. Leiden: Brill, pp. 121–45. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh. 2001. Stūpa, Sūtra, and Śarīra, c. 656–706 CE. Buddhist Studies Review 18: 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bentor, Yael. 1995. On the Indian Origins of the Tibetan Practice of Depositing Relics and Dhāraṇīs in Stūpas and Images. Journal of the American Oriental Society 115: 248–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, Daniel. 1991. The Pratītyāsamutpādagāthā and its Role in the Medieval Cult of the Relics. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 14: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, Daniel. 1995. Sūtra on the Merit of Bathing the Buddha. In Buddhism in Practice. Edited by Donald Lopez Jr. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chandawimala, Rangama. 2013. Buddhist Heterodoxy of Abhayagiri Sect: A Study of the School of Abhayagiri in Ancient Sri Lanka. Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2002a. Monks and Monarchs, Kinship and Kingship. Kyoto: Italian School of East Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2002b. Śarīra and Scepter: Empress Wu’s Political Use of Buddhist Relics. The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 25: 33–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Kyŏngmi (Joo Kyeongmi周炅美). 2011. 8~11 segi tong Asia ta’p nae tarani pongan ŭi pyŏnch’ŏn” 8–11世紀 東아시아 塔內 陀羅尼 奉安의 變遷. Misulsa wa sigak munhwa (미술사와 시각문화) 10: 264–93. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, Paul F. 2008. Notes on the Term ‘Dhāraṇī’ in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Thought. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 71: 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, Paul. 2014. The Body Incantatory: Spells and the Ritual Imagination in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De, Xin (德新), Hanjun Zhang (張漢君), and Renxin Han (韓仁信). 1994. Neimenggu Bailinyouqi Qingzhou Baita faxian Liaodai fojiao wenwu (內蒙古巴林右旗慶州白塔發現遼代佛敎文物). Wenwu (文物) 12: 4–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dikshit, Rao Bahadur K. N. 1938. Excavations at Paharpur, Bengal, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India 55. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. [Google Scholar]

- Edgren, Soren. 1972. The Printed Dhāraṇī-sūtra of A.D. 956. Bulleting of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 44: 141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 1991. The Rhetoric of Immediacy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fontein, Jan. 1995. Relics and Reliquaries, Texts and Artifacts. In Function and Meaning in Buddhist Art: Proceeding of a Seminar at Leiden University, 21–24 October 1991. Edited by K. R. van Kooij and Henny van der Veere. Groningen: Egbert Forsten, pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A. 1946. A Buddhist Tract on a Stone Inscription in the Cuttack Museum. EI 26: 171–74. [Google Scholar]

- Goble, Geoffrey C. 2019. Chinese Esoteric Buddhism: Amoghavajra, the Ruling Elite, and the Emergence of a Tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Arlo. 2014. Written Traces of the Buddhist Past: Mantras and Dhāraṇīs in Indonesian Inscriptions. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 77: 137–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, Jens-Uwe. 2009. From Words to Books: Indian Buddhist Manuscripts in the First Millennium CE. In Buddhist Manuscript Cultures: Knowledge, Ritual, and Art. Edited by Stephen C Berkwitz, Juliane Schober and Claudia Brown. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, Atsuko (服部敦子). 2010. Sen Kōkuchu hachiman yonsen tō o meguru genjō to kadai 銭弘俶八万四千塔をめぐる現状と課題. Ajia yūgaku (アジア遊学) 134: 26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashidera, Shōshun (林寺正俊). 2013. Hōkyōin darani kyō no bonkan hikaku (宝篋印陀羅尼經の梵漢比較). In Kongōji zō Hōkyōin darani kyō (金剛寺藏寶篋印陀羅尼經). Edited by Kokusai bukkyōgaku daigakuin daigaku Nihon koshakyō kenkyūjo Bunkashō senryaku purojekuto jikkō iinkai (國際佛教學大學院大學日本古寫經研究所文科省戰略プロジェクト實行委員會). Tokyo: Kokusai bukkyōgaku daigakuin daigaku Nihon koshakyō kenkyūjo Bunkashō senryaku purojekuto jikkō iinkai, pp. 167–200. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shih-shan. 2011. Early Buddhist Illustrated Prints in Hangzhou. In Knowledge and Text Production in an Age of Print: China, 900–1400. Edited by Lucille Chia and Hilde De Weerdt. Leiden: Brill, pp. 135–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah, and Rob Linrothe. 2014. Introduction: Buddhist Visual Culture. History of Religions 54: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Yasuko (小島裕子). 2013. Shohon taikō Hōkyōin darani kyō (諸本對校『寶篋印陀羅尼經』). In Kongōji zō Hōkyōin darani kyō. Tokyo: Kokusai bukkyōgaku daigakuin daigaku Nihon koshakyō kenkyūjo Bunkashō senryaku purojekuto jikkō iinkai, pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Konow, Sten. 1929. Kharoshṭhī Inscriptions with the Exception of Those of Aśoka, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum 2.2. Calcutta: Government of India, Central Publication Branch. [Google Scholar]

- Kornicki, Peter. 2012. The Hyakumantō Darani and the Origins of Printing in Eighth-Century Japan. International Journal of Asian Studies 9: 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art. 2011. Leeum Samsung Museum of Art: Traditional Art Collection. Seoul: Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuxin (黎毓馨). 2009a. Ayuwangta shiwu faxian yu chubu zhengli (阿育王塔實物的發現與初步整理). Dongfang bowu (東方博物) 2: 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuxin (黎毓馨), ed. 2009b. Tian fu di zai: Leifeng ta Tiangong Ayuwang ta Tezhan (天覆地載: 雷峰塔天宮阿育王塔特展). Xianggang: Zhongguo wenhua yishu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuxin (黎毓馨), ed. 2010. Di yong Tianbao: Leifeng ta ji Tang Song Fojiao Yizhen Tezhan (地涌天寶: 雷峰塔及唐宋佛教遺珍特展). Xianggang: Zhongguo Wenhua yishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuxin (黎毓馨), ed. 2011. Wuyue Shenglan: Tang Song zhi jian de Dongnan Leguo (吳越勝覽: 唐宋之間的東南樂國). Beijing: Zhongguo shudian. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Guangming (林光明). 2008. Fangshan Mingzhou ji (房山明呪集). Taibei: Jiafeng chubanshe, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wei-cheng. 2019. Broken Bodies: The Death of Buddhist Icons and Their Changing Ontology in Tenth- through Twelfth-Century China. In Refiguring East Asian Religious Art: Buddhist Devotion and Funerary Practice. Edited by Wu Hung and Paul Copp. Chicago: Center for the Art of East Asia, University of Chicago and Art Media Resources, pp. 80–105. [Google Scholar]

- Linrothe, Rob. 1999. Ruthless Compassion: Wrathful Deities in Early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism. Boston: Shambala. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shu-fen (劉淑芬). 2003. Muchuang jingchuag yanjiu zhi san (墓幢—經幢硏究之三). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo jikan (中央硏究院歷史語言硏究所集刊) 74: 673–763. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, Richard D., II. 2005. Dhāraṇī and Spells in Medieval Sinitic Buddhism. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 28: 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, Richard D., II. 2011. Practical Buddhist Thaumaturgy: The Great Dhāraṇī on Immaculately Pure Light in Medieval Sinitic Buddhism. Journal of Korean Religions 2: 33–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, Richard D., II. 2019. Dhāraṇī and Mantra in Contemporary Korean Buddhism: A Textual Ethnography of Spell Materials for Popular Consumption. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 42: 361–403. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Umakanta. 2016. Dhāraṇīs from the Buddhist Sites of Orissa. Pratnatattva: Journal of the Dept. of Archaeology 22: 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, Debala. 1981. Ratnagiri 1958–1961. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mudiyanse, Nandasena. 1967. Mahāyāna Monuments in Ceylon. Colombo: M.D. Gunasena. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Julia K. 1994. The Evolution of Buddhist Narrative Illustration in China after 850. In Latter Days of the Law: Images of Chinese Buddhism, 850–1850. Edited by Marsha Weidner. Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, pp. 125–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Genmyō (小野玄妙). 1917. Goetsu ō Sen Kōshuku zō kintotō shikō (吳越王錢弘俶造金塗塔私考). In Bukkyō no Bijutsu oyobi Rekishi (佛敎の美術及び歷史). Tokyo: Bussho kenkyūkai, pp. 617–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Eiji (小野英二). 2008. Hōkyōin kyō ki ni miru Nihon no Aikuōtō shinkō juyō no ichi danmen (宝篋印経記にみる日本の阿育王塔信仰受容の一断面). Nara bijutsu kenkyū (奈良美術研究) 7: 182–94. [Google Scholar]

- Orzech, Charles D. 2011. Esoteric Buddhism in the Tang: From Atikūtạ to Amoghavajra (651–780). In Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Edited by Charles D. Orzech, Henrik H. Sørensen and Richard K. Payne. Leiden: Brill, pp. 261–85. [Google Scholar]

- Revire, Nicolas. 2016. The Enthroned Buddha in Majesty: An Iconological Study. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzinger, Justin, and Marcus Bingenheimer. 2006. Whole-body Relics in Chinese Buddhism Previous Research and Historical Overview. The Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies 7: 37–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield, John M. 2014. Notes on the Jewel Casket Sutra in Japan. In China and Beyond in the Medieval Period: Cultural Crossings and Inter-Regional Connections. Edited by Dorothy C. Wong and Gustav Heldt. New Delhi and New York: Manohar Publishers and Cambria Press, pp. 387–402. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer-Schaub, Cristina A. 1994. Some Dhāraṇī Written on Paper Functioning as Dharmakāya Relics: A Tentative Approach to PT 350. In Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Fagernes 1992. Edited by Per Kvaerne. Oslo: The Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture, vol. 1, pp. 711–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 1998. Relic. In Critical Terms for Religious Studies. Edited by Mark C. Taylor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 256–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 2005a. The Bodhigarbhālaṇkāralakṣa and Vimaloṣṇīṣa Dhāraṇīs: Two Sources for the Practice of Buddhism in Medieval India. In Figments and Fragments of Mahāyāna Buddhism in India: More Collected Papers. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, pp. 314–44. First published 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 2005b. The Text on the Dhāraṇī Stones from Abhayagiriya: A Minor Contribution to the Study of Mahāyāna Literature in Ceylon. In Figments and Fragments of Mahāyāna Buddhism in India. O’ahu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 306–13. First published 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sekine, Shun’ichi (關根俊一). 1987. Sen Kōshūku hachiman yonsen tō ni tsuite (銭弘俶八万四千塔について). MUSEUM 441: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Hsueh-man. 2001. Realizing the Buddha’s Dharma-body during the Mofa Period: A Study of the Liao Buddhist Relic Deposits. Artibus Asiae 61: 263–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Hsueh-man. 2019. Authentic Replicas: Buddhist Art in Medieval China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Zhiru. 2013. The Architectural and Religious Functions of Baoqieyin Dhāranī Sūtra Manuscripts at Leifeng Pagoda. In Kongōji zō Hōkyōin darani kyō. Tokyo: Kokusai bukkyōgaku daigakuin daigaku Nihon koshakyō kenkyūjo Bunkashō senryaku purojekuto jikkō iinkai, pp. 232–16, (reverse pagination). [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Zhiru. 2014. From Bodily Relic to Dharma Relic Stupa: Chinese Materialization of the Aśoka Legend in the Wuyue Period. In India in the Chinese Imagination. Edited by John Kieschnick and Meir Shahar. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, pp. 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, Peter. 2003. Traces of the Dharma: Preliminary Reports on Some ye dhammā and ye dharmā Inscriptions from Mainland South-East Asia. Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient 90/91: 273–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauch, Ingo. 2009. Two Stamps with the Bodhigarbhālaṁkāralakṣa Dhāraṇī from Afghanistan and Some Further Remarks on the Classification of Objects with the Ye dharmā Formula. In Prajñādhara: Essays on Asian Art, History, Epigraphy and Culture in Honour of Gouriswar Bhattacharya. Edited by Gerd J.R. Mevissen and Arundhati Banerji. New Delhi: Kaveri Books, vol. 1, pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, John S. 2004. Relics of the Buddha. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, John S. 2007. The Buddha’s Funeral. In The Buddhist Dead: Practices, Discourses, Representations. Edited by Bryan J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I. Stone. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Kimiaki (田中公明). 2014. Orissashū Udayagiri II shutsudo no sekkoku darani ni tsuite (オリッサ州ウダヤギリII出土の石刻陀羅尼について). Tōyō bunka kenkyūjō kiyō (東洋文化研究所紀要) 166: 134–24, (reverse pagination). [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, Pramod Kumar. 2011. Further Excavations at Udayagiri-2, Odisha (2001–03). Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiang, Katherine R. 2010. Buddhist Printed Images and Texts of the Eighth-Tenth Centuries: Typologies of Replication and Representation. In Esoteric Buddhism at Dunhuang: Rites and Teachings for This Life and Beyond. Edited by Matthew T. Kapstein and Sam Van Schaik. Leiden: Brill, pp. 201–52. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeersch, Sem. 2016. Beyond Printing: Looking at the Use and East Asian Context of Dhāraṇī Sūtras in Medieval Korea. Chonggyohak yŏn’gu (종교학연구) 34: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Eugene Y. 2004. Of the True Body: The Famen Monastery Relics and Corporeal Transformation in Tang Imperial Culture. In Body and Face in Chinese Traditional Culture. Edited by Wu Hung and Katherine T. Mino. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 79–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Tsui-ling (王翠玲). 2011. Yongming Yanshou de xiuxing xilun: Yi youguan zhaomu er ke de tuoluoni weizhu (永明延壽的修行析論: 以有關朝暮二課的陀羅尼為主). Zhongzheng daxue zhongwen xueshu niankan (中正大學中文學術年刊) 18: 247–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 2018. Buddhist Pilgrim-Monks as Agents of Cultural and Artistic Transmission: The International Buddhist Art Style in East Asia, ca. 645–770. Singapore: NUS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Li-qiang (徐立強). 2018. Tongxing ban tuoluoni bei zhi neirong jiedu (通行版陀羅尼被之內容解讀). Zhonghua foxie yanjiu (中華佛學研究) 19: 149–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, Satoshi (山崎覚士). 2010. Chūgoku godai kokka ron (中国五代国家論). Kyoto: Shibunkaku shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi, Mikiyasu (柳幹康). 2015. Eimei Enju to Sugyōroku no kenkyū (永明延寿と『宗鏡録』の研究). Kyoto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Sŭnghye (Lee Seunghye 李勝慧). 2015. Koryŏ ŭi Owŏl p’an Pohyŏbin kyŏng suyong kwa ŭmi (高麗의 吳越板 『寶篋印經』 수용과 의미). Pulgyohak yŏn’gu (불교학연구) 43: 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Sŭnghye (Lee Seunghye 李勝慧). 2018. Chungguk myojang tarani ŭi sigakmunhwa: Tang kwa Yo ŭi sarye rŭl chungsim ŭro (중국 墓葬 陀羅尼의 시각문화: 唐과 遼의 사례를 중심으로. Pulgyohak yŏn’gu (불교학연구) 57: 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Yiengpruksawan, Mimi H. 1987. One Millionth of a Buddha: The Hyakumantō Dhāraṇī in the Sheide Library. Princeton University Library Chronicle 48: 224–38. First published 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xiumin (張秀民). 1978. Wudai Wuyue guo de yinshua (五代呉越国的印刷). Wenwu (文物) 12: 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhejiangsheng wenwu kaogu yanjiusuo (浙江省文物考古硏究所). 2002. Leifeng yizhen (雷峰遺珍). Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | On the concept of dhāraṇī, see (McBride 2005; Copp 2008). |

| 2 | (T 261, 8: 868c13). |

| 3 | Some twenty kinds of dhāraṇīs and mantras are known to have entered relic crypts of East Asian Buddhist pagodas. See (Chu 2011, p. 264). |

| 4 | Throughout this paper, I will refer to the Indian Buddhist funerary monument erected for the relics of the Buddha as stūpas, while referring to their East Asian counterparts that typically feature multiple stories as pagodas. However, I will refer to artifacts imitating the form of and making connections to the Indian prototype as stūpas, regardless of their place of origin. |

| 5 | Hereafter, I will refer to this text in its entirety as the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra and the spell given at the end of the sutra as the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī. |

| 6 | It was first published in 1982 and reprinted in a collection of his papers. See (Schopen [1982] 2005b). |

| 7 | The study was first published in Japanese and later in English with slight changes. See (Baba 2012, 2017). |

| 8 | My approach here is informed by (Kim and Linrothe 2014; Acri 2016). |

| 9 | It should be noted that practices of the Karaṇḍamudrā Dhāraṇī were not only widespread but also long-standing, and continue well into contemporary times. For discussions on the contemporary examples from China and Korea, see (Xu 2018; McBride 2019, p. 392). |

| 10 | Amoghavajra’s translation is preserved in Yiqie rulai xin mimi quanshen sheli baoqieyin tuoluoni jing, see (T 1022A, 19: 710–12). Dānapāla’s is found in Yiqie rulai zhengfa mimi qieyin xin tuoluoni jing, see (T 1023, 19: 715–17). T 1022B, whose translation is also attributed to Amoghavajra, is a Japanese temple edition. Collation of T 1022A and T 1022B, along with three Japanese manuscript versions, is available in (Kojima 2013). |

| 11 | For a summary of the sutra, see (Schopen [1982] 2005b, pp. 308–10). |

| 12 | (T 1022A, 19: 710b28–c2). |

| 13 | (T 1022A, 19: 711a18–25; Shi 2014, pp. 104–5). |

| 14 | (T 1022A, 19: 711a28–b2). |

| 15 | For a word-by-word reading of the dhāraṇī, see (Hayashidera 2013). |

| 16 | For more on this practice, see (Copp 2014, pp. 33–39). Although dhāraṇī sutras prescribing this practice have been transmitted in Chinese translation from the seventh century, the actual practice seems to have appeared in India during the middle centuries of the first millennium. See (Bentor 1995, 252ff). |

| 17 | (Boucher 1991). The earliest example is likely the one incised in Kharosthī script on the base of a copper stūpa from the Kurram valley in ancient Gandhāra. The inscription is datable to the second century CE. See (Konow 1929, pp. 152–55, inscription LXXX). For examples from southeast Asia, see (Skilling 2003; Griffiths 2014). |

| 18 | (T 2087, 51: 920a22–b3; Boucher 1991, pp. 7, 4–5). Yijing’s description of this cultic practice is found in Nanhai jigui neifa zhuan, see (T 2125, 54: 226c15–27; Boucher 1995, p. 61). For more on the Tang pilgrims and the practice of pratītyāsamutpādagāthā, see (Wong 2018, pp. 23–55). |

| 19 | (T 1723, 34: 809c15–18). |

| 20 | (T 699, 16: 801b12–15). |

| 21 | (T 698, 16:800a6–11; Boucher 1995, p. 65; Wong 2018, pp. 46–47). |

| 22 | For a detailed study on the former, see (McBride 2011). |

| 23 | I owe this observation to (Hartmann 2009, p. 104). |

| 24 | The notion of “broken bodies,” in terms of icons and relics, has been recently studied in (Lin 2019). |

| 25 | The Lotus Sūtra uses the term in two senses. It alludes to the Lotus Sūtra itself while referring to the undispersed body of the ancient Buddha Prabhūtaratna. See (T 262, 9: 31b27–29, 32c8–18). |

| 26 | (T 384, 12: 1030a25–28). |

| 27 | (T 2121, 53: 29b8–9; T 2122, 53: 598c9–599a12). |

| 28 | (Strong 2004, pp. 44–47; Lin 2019, p. 85). The rhetoric of completeness was employed in a different type of relics, i.e., the mummified remains of deceased Chan masters in medieval China and beyond. See (Faure 1991, pp. 148–78; Ritzinger and Bingenheimer 2006). |

| 29 | (T 1022A, 19: 710b28–c2). |

| 30 | Similar rhetoric is also employed in (T 1025, 19: 724a8–10). |

| 31 | (T 1008, 19: 672a9). |

| 32 | (T 1022A, 19: 711a18–25; Shi 2014, pp. 104–5). |

| 33 | (T 1022A, 19: 711b27–29). |

| 34 | The relic assemblage was found in the upper crypt of the Shijiafoshelita 釋迦佛舍利塔 in Bairin Right Banner (dated 1049). See (De et al. 1994, p. 16, 20; Shen 2001, pp. 271–72). |

| 35 | (T 1008, 19: 672b29–c11; Copp 2014, pp. 36–37). For a discussion of the four kinds of relics, see (Schopen [1985] 2005a, pp. 319–20). |

| 36 | (T 1008, 19: 672c7–14). |

| 37 | The stone slab, initially housed in Cuttack Museum, is now in the collection of Odisha State Museum, see (Ghosh 1946; Schopen [1985] 2005a, pp. 327–29). |

| 38 | Amoghavajra’s memorial is found in Daizong zhaozeng sikong dabian zhengguangzhi sanzangheshang biaozhi ji (T 2120, 52: 840a12–840b12). For an English translation of the memorial, see (Goble 2019, pp. 207–9). It is curious that the accompanying list only gives titles of 71 texts, see (T 2120, 52: 839a26–840a11). A reference to the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra is found in (T 2120, 52: 839b17). |

| 39 | (T 2156, 55: 766c12–766c16). For references to the Karaṇḍamudrā Sūtra, see (T 2156, 55: 767a18; T 2156, 55: 768a11–14). |

| 40 | See, for instance, (T 2056, 50: 293a15–16). |

| 41 | (T 2120, 52: 848c2–c14). See also (Baba 2017, pp. 124–25; Goble 2019, pp. 36–37). |

| 42 | Fifteen-odd dhāraṇī sutras are said to have been translated by Amoghavajra, see (T 2120, 52: 839a26–840a11). |

| 43 | Schopen compares the Abhayagiri version with the Tibetan one and concludes that they are identical. See (Schopen [1982] 2005b, pp. 306–13). |

| 44 | For comparisons of the texts, see (Chandawimala 2013, pp. 130–32; Hayashidera 2013). |

| 45 | For Romanized texts of the inscriptions Nos. 8 and 27, see (Trivedi 2011, p. 217, 230–31 [Pl. CXLIV], 253–54 [PL. CLXIII]). |

| 46 | (Tanaka 2014, pp. 131–27). See also (Mishra 2016, p. 78). |

| 47 | (T 1008, 19: 671b8–b25, 674b26–27, 674b29). Inscriptions of the mūlamantra were found at the sites of stūpas 2 and 253 at Ratnagiri and identified on stone slab inscription No. 30 (ca. 9–10th century) from the Udayagiri II site. See (Mitra 1981, p. 43, 99; Trivedi 2011, p. 255, Pl. CLXII). For more examples, see also (Schopen [1985] 2005a, pp. 338–39; Strauch 2009). For a Javanese example, see (Griffiths 2014, pp. 161–64). |

| 48 | Cf. (T 1022A, 19: 711c02–25; T 1022B, 19: 713c24–a18; T 1023, 19: 717a12–b9). |

| 49 | Cf. (T 1025, 19: 724a13–18). Notably, it is not the main dhāraṇī of the sutra but a short one appearing in fascicle 2 to be inserted inside a stūpa as a substitute for the bodily relic of the Buddha. See (Tanaka 2014, p. 129). This dhāraṇī also occurs on the back of the Jaṭāmukuṭa Lokeśvara image at Temple no. 7 of Ratnagiri and other major Indian Buddhist sites such as Nalanda, Paharpur, and Gilgit. See (Mitra 1981, p. 104; Dikshit 1938, pp. 83–84). For an example from Dunhuang, see (Scherrer-Schaub 1994). For Balinese clay sealing stamped with this dhāraṇī, see (Griffiths 2014, pp. 181–83). |

| 50 | (Mishra 2016, p. 78). For a discussion of the image, see (Linrothe 1999, p. 109, Fig. 90). |

| 51 | (Chu 2011, pp. 275–80). For a study on the Liao manifestation of the practice, see (Shen 2001). |

| 52 | For instance, inscriptions of the Mahāpratisarā Dhāraṇī, often found on or near the body of the deceased within tombs, point to their function as amulets. See (Copp 2014, pp. 59–140). See also (Liu 2003; Yi 2018). |

| 53 | (Yiengpruksawan [1986] 1987). For its impact on printing, see (Kornicki 2012). |

| 54 | Archaeological evidence that testifies the practice of the Sūtra of the Great Dhāraṇī on Stainless Pure Light in the pre-Liao period is meager at best. |

| 55 | For Empress Wu’s vow, see (Barrett 2001, p. 34; Chen 2002b, p. 62). For more on this text and related practice in Korea, see (McBride 2011). |

| 56 | Eugene Wang notes that the term “true body” came to refer to the physical relics of the Buddha after Empress Wu’s time. See (Wang 2004). |

| 57 | The collection, neither found in the Taishō or Zokuzōkyō canon, is preserved in the Fangshan Stone Canon. See (F 1071, 28: 25a2–b13). A reconstruction of the dhāraṇī in Siddhaṃ script and transliteration are found in (Lin 2008, pp. 143–47). |

| 58 | (F 1071, 28: 24a12–b19). |

| 59 | (T 2161, 55: 1061a25, 1063c7). |

| 60 | (T 2167, 55: 1079c2223; T 2173, 55: 1103b4). For more on the reception of the text in Japan, see (Rosenfield 2014; Baba 2017, pp. 132–37). |

| 61 | (T 2035, 49: 206c1–4). |

| 62 | For an overview of the textual accounts of Qian Chu’s miniature stūpas and examples archaeologically discovered in China and Japan, see (Sekine 1987; Li 2009a; Hattori 2010; Li 2011, pp. 154–74). |

| 63 | The four sides of the reliquaries are adorned with a narrative illustration based on jātaka tales. Such narrative illustrations had fallen out of favor by the tenth century. |

| 64 | The colophon reads: 天下都元帥 吳越國王錢弘俶 印寶篋印經 八萬四千卷 在寶塔內供養 顯德三年 丙辰歲記. |

| 65 | For more information, see (Zhang 1978, p. 74; Li 2009a, pp. 40–41). |

| 66 | The colophon reads: 吳越國王錢俶 敬造寶篋印經 八萬四千卷 永充供養 時乙丑歲記. |

| 67 | The colophon reads: 天下兵馬大元帥 吳越國王錢俶 造此經八万四千卷 捨入西關塼塔 永充供養 乙亥八月日記. |

| 68 | For a recent discussion of this storage method, see (Shi 2013). |

| 69 | For more on Emperor Wen’s relic distribution campaigns, see chapters 2 and 3 of (Chen 2002a). For Empress Wu’s vow, see (Barrett 2001, p. 34; Chen 2002b, p. 62). |

| 70 | For more on the notion of the “true king” in the changing political order of the tenth century, see (Yamazaki 2010, pp. 102–32). See also (Ono 2008; Shi 2014, pp. 105–9; Shen 2019, p. 200). |

| 71 | This has been pointed out since the beginning of studies on Qian’s miniature stūpas. For a classic treatment of the issue, see (Ono 1917). |

| 72 | On a related note, Yanshou practiced the recitation of dhāraṇīs and mantras, twelve in total, in the dawn and evening daily. See (Wang 2011). |

| 73 | Baba Norihisa suggests this interpretation based on Yanagi’s reading of Yanshou’s Zongjing lu 宗鏡錄. See (Baba 2017, pp. 131–32). |

| 74 | This may have been caused by the limited space on the stone tablets. It is plausible that the text was reproduced in its entirety when they were written on palm leaves. |

| 75 | My definition of a frontispiece is informed by (Murray 1994, pp. 136–37; Tsiang 2010, pp. 205–14). |

| 76 | For more on the two frontispieces, see (Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art 2011, pp. 176–81; Tsiang 2010, pp. 205–7). |

| 77 | The earliest known Korean edition of the text is dated 1007. For more on this issue, see (Yi 2015). See also (Vermeersch 2016). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).