Abstract

The Parokhet, or sacred curtain, was an important item of cultic paraphernalia in the ancient Near East. It is known from the Sumerian and Akkadian texts, the biblical tradition, the Second Temple in Jerusalem, Greek temples, and synagogues of the Roman and Byzantine eras, and is still in use today. We suggest that such a sacred curtain is depicted on several of the miniature clay objects known as portable shrines. In Egypt, thanks to the dry climate, a miniature curtain of this kind has indeed been preserved in association with a portable shrine. Depictions of shrines on Egyptian sacred barks also include life-size curtains.

1. Introduction

Among the various objects used as cultic paraphernalia in the ancient Near East, there is a notable assemblage of objects shaped in the form of a building, and hence known as architectural models. These objects have received much attention and have been studied extensively over the years. There are several monographs dedicated to the systematic presentation of the various relevant items (Bretschneider 1991; Muller 2002, 2016; Katz 2016), as well as numerous articles devoted to the presentation of a specific object (see, for example, Kletter et al. 2010; Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2013, 2015, 2016).

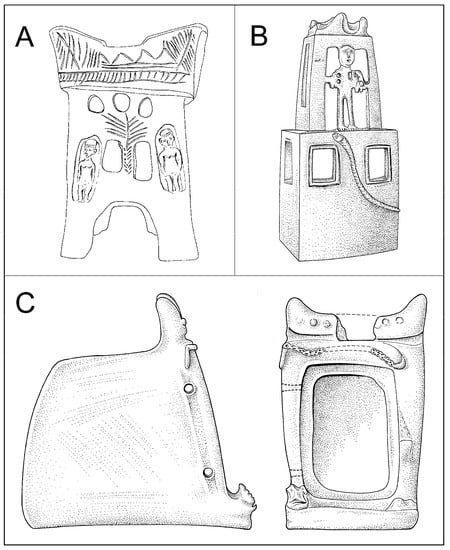

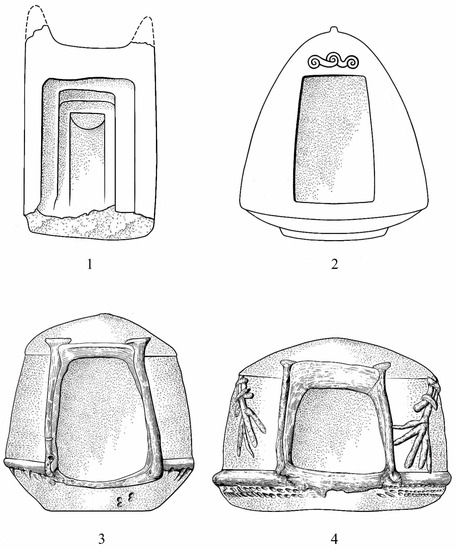

In a previous study (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2015), we divided the architectural models into three categories (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Typology of the main types of the objects commonly known as building models: (A). tower-like altar (Tel Rehov; Mazar and Panitz-Cohen 2008, p. 43); (B). model building (Beth-Shean; Rowe 1940); (C). closed box (Tel Rekhesh; Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2015).

A. Tower-like items with a flat top and four horns, one on each corner. These apparently functioned as altars (see, for example, Mazar and Panitz-Cohen 2008, p. 43).

B. Model buildings with doors, windows, and human figures on all four sides. These are in fact miniature structures (see, for example, Kletter et al. 2010).

C. Closed boxes with a single opening in the shape of a door. The side with the opening may be plain or elaborately decorated to represent the façade of a building. There is usually a closing device near the opening, an indication of a door that, with a few exceptions, has usually not survived. These objects were used as miniature shrines to contain divine symbols, like the metal figurine uncovered in the “Calf Temple” of Ashkelon (Stager 2008) or the clay figurines attached to the wall at Tell Qasile (Mazar 1980, pp. 82–84).

Here, we relate only to the third category, defined as portable shrines, although other terms, such as “naos” or “naiskos” (Mazar 1980, pp. 82–84; Moscati 1988) or “tabernacle” (de Miroschedji 2001), have been suggested for these objects as well. The portable shrine is understood as a miniature depiction of a temple, or more specifically the Holy of Holies of a temple. Inside these objects, a figurine of a god was kept, as we know from Tell Qasile (Mazar 1980, pp. 82–84) and Ashkelon (Stager 2008).

As these are miniature depictions of real temples, they are decorated with characteristic architectural features of temples, such as two pillars or a pair of lions in front of the entrance. These similarities have long been recognized (Bretschneider 1991; Muller 2002; Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, pp. 116–17). We now wish to add another decorative element that characterized temples—the Parokhet, a sacred curtain that was hung before the Holy of Holies. It seems that such a curtain is represented on some of the portable shrines, a fact that has so far been overlooked.

2. The Parokhet

Parokhet is not a Semitic word, but derives from barag in the Sumerian language of third-millennium BCE Mesopotamia, a word meaning “dais, divine throne room, sanctuary” (CAD 2005, pp. 148, 185). It is thus associated with cult and temples. Later on, Akkadian texts of the Old Babylonian era (the first half of the second millennium BCE) contain two similar, but different, terms: pariktu and parakku.

Pariktu: This word, meaning “curtain, obstacle” in Akkadian, is documented in Old Babylonian and in Neo-Assyrian ritual texts (CAD 2005, p. 185). Only the high priest was allowed behind the pariktu, the curtain before the Holy of Holies.

Parakku: This term means “dais, divine throne room, sanctuary” (CAD 2005, pp. 148, 185). A list of 48 small shrines in Babylon designates them as parakku, the “seat” of a god that might be located either inside or outside a temple, in city gates and streets (George 1992, pp. 12, 65, 67, 99). In Babylon, in the Ishtar gate and at the gate of the temple of Ningišzida, a dais against the gate (Cella C) was identified as “parak Assare” (May 2013, pp. 84–85). The kalû, a Babylonian institutional figure gradually imported into Assyria, was one of the most important personnel in the Assyrian temple cult in the 7th century BCE. His status allowed him to enter the parakku, the inner cella of the temple (Gabbay 2014, p. 121).

Thus, while the term parakku was used to describe a shrine or temple, the term pariktu relates to the curtain that delineated the Holy of Holies from the rest of the building. This sacred curtain has been discussed by various scholars (Menzel 1981, vol. 2, T.93:43; Villard 2010, pp. 392, 397; Gespa 2018, p. 443). It is also mentioned in a letter from Ugarit relating to the 13th century BCE temple of Baal in Sidon, where it is located “inside the sanctuary” (Bordreuil 2006, p. 161; 2007, p. 95; Yon and Arnaud 2001, pp. 267, 269–71).

Essentially the same word is used in the Bible to describe the sacred curtain hung before the sacred space (Van der Meulen 1985; Gane and Milgrom 2003; Gurtner 2006; Bordreuil 2007, p. 95). The account of the Tabernacle states: “You shall make a curtain [prkt] of blue, purple, and crimson yarns, and of fine twisted linen; it shall be made with cherubim skillfully worked into it. You shall hang it on four pillars of acacia overlaid with gold, which have hooks of gold and rest on four bases of silver. You shall hang the curtain [prkt] under the clasps, and bring the ark of the covenant in there, within the curtain [prkt]; and the curtain [prkt] shall separate for you the holy place from the most holy” (Exod 26, pp. 31–33, NRSV). The same term is used to describe a similar curtain in the temple of Solomon in Jerusalem: “And Solomon made the curtain [prkt] of blue and purple and crimson fabrics and fine linen, and worked cherubim into it” (2 Chr 3:14). In some biblical traditions (Exod 35:25; 2 Kgs 23:7), women are mentioned as the producers of cultic textiles; women were indeed involved in spinning and weaving in the ancient Near East from the protohistoric era onward (Garfinkel 2018).

The Parokhet is mentioned several times in relation to the Second Temple in Jerusalem. In around 168 BCE, Antiochus Epiphanes plundered the temple; the list of stolen items includes “the golden altar, the lampstand for the light, and all its utensils, the table for the bread, the cups for drink offering, the bowls, the golden censers, the curtain, the crowns, and the gold decoration on the front of the temple” (1 Macc 1:22). It is interesting to see that a perishable textile is mentioned among the most precious golden objects.

As summarized by Elledge and Netzer (2015), at least eleven different ancient literary documents dating from ca. 200 BCE to 200 CE provide significant information about the curtain of the Second Temple. These include documents from the Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, Josephus, the Dead Sea Scrolls, rabbinical literature, and the New Testament.

Josephus described the Parokhet of the Temple in detail: “Before these doors there was a veil of equal largeness with the doors. It was a Babylonian curtain, embroidered with blue, and fine linen, and scarlet, and purple, and of a contexture that was truly wonderful. Nor was this mixture of colors without its mystical interpretation, but was a kind of image of the universe; for by the scarlet there seemed to be enigmatically signified fire, by the fine flax the earth, by the blue the air, and by the purple the sea; two of them having their colors the foundation of this resemblance; but the fine flax and the purple have their own origin for that foundation, the earth producing the one, and the sea the other. This curtain had also embroidered upon it all that was mystical in the heavens, excepting that of the [twelve] signs, representing living creatures” (War of the Jews V.5.4; and see further discussions in Ilan 2017). In 70 CE, when the temple objects were brought to Rome, it is told that emperor Vespasian had the golden vessels put in the new Temple of Peace, but the Scrolls of the Law and the purple curtains of the sacred place were kept in the palace (War of the Jews VII.5.7). A similar account, together with other traditions about the Parokhet in Rome, appears in the Babylonian Talmud (Ilan 2017).

Parokhet is also mentioned in the New Testament. At Jesus’ death “the curtain of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom” (Matt 27:51; Mark 15:38; Luke 23:45). At Qumran, the Temple Scroll, dated to the 1st century CE, describes the temple revealed by God to Moses, which includes a golden curtain before the Holy of Holies (Yadin 1983, pp. 27–28). These fantastic descriptions of the cultic curtain in the Tabernacle and in the First and Second Temple kindled the imagination of later medieval artists in the Byzantine world and the Latin West (Lidov 2014).

There is a Greek tradition about an offering made to the temple of Zeus in Olympia, “a woolen curtain, adorned with Assyrian weaving and Phoenician purple, which was dedicated by Antiochus” (Pausanius, Description of Greece V.12.2). It is interesting to compare “Assyrian weaving” to Josephus’ “Babylonian curtain” of the Temple in Jerusalem, both references to cultic curtains woven in Mesopotamian style.

Pictorial representations of the Parokhet are known from various synagogues, such as the wall paintings of the Dura Europos synagogue in Syria, dated to the 3rd century CE (Kraeling 1979, Pl. LX). The building even contained a niche for the Torah scrolls (Kraeling 1979, p. 16) with depressions above the niche that could be used to hold hooks for the Parokhet (Du Mesnil du Buisson 1939, p. 10). Such cultic curtains are also depicted on the mosaic floors of several Jewish and Samaritan synagogues (Mumcuoglu and Garfinkel 2020, p. 120, Figures 8 and 9; Rosenthal-Heginbottom 2009, Figures 9 and 14). It has been suggested that these depictions do not represent cultic furnishings of the synagogue but convey a spiritual message related to the Temple (Rosenthal-Heginbottom 2009, p. 169).

In Syrian Christian sources from the 4th century CE onward there are several references to the use of altar curtains. They were conceived as an interactive system of devices concealing the door of the sanctuary barrier. This influence has been noted in medieval Byzantine churches, as well as in Ethiopian churches from the 11th century CE (Schattner-Rieser 2012, p. 19; Lidov 2014). Later on, the curtain was perceived to be the threshold of what is beyond visibility, the presence of the invisible God in the Christian religion (Constas 2006).

As a matter of fact, the very same cultic curtain and the identical term “Parokhet” are still in use today in modern Jewish synagogues (Yaniv 2019, p. 29). There is probably no other cultic object that has preserved its original function and name for nearly five thousand years and in different cultures. The long survival of both the cultic curtain and its original name points to the central importance of the Parokhet in the eyes of worshipers. It is, hence, no surprise that the Parokhet was depicted on miniature representations of temples.

3. Archaeological Examples of the Sacred Curtain

As they were made from perishable materials like wool or linen, not one example of an ancient Parokhet has survived in Mesopotamia or the Levant. In Egypt, however, thanks to the dry climate, there are examples of textiles that functioned in cultic contexts, such as portable shrines and burials.

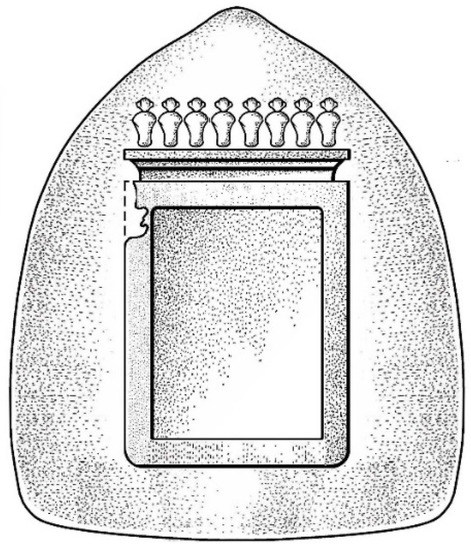

The most relevant example is a simple portable shrine made of clay, uncovered at Abydos 140 years ago (Mariette 1880, catalog number 1429, p. 555; Roeder 1914, pp. 135–37; Megahed and Bassir 2015, p. 144, Figure 1). The rounded clay object has a rectangular opening in front, with a thick frame on three sides topped by an emphasized lintel. This lintel is decorated by a projecting row of eight uraei snakes crowned by sun-disks. The wide base of the artifact probably held an image or emblem of a deity, presumably Osiris (Figure 2). This object (CG 70041, Cairo Egyptian Museum), which belonged to the goldsmith Sankhuher, was found in the so-called “nécropole des chanteuses” among stelae of the late 20th Dynasty, and hence is dated to the 12th century BCE. Here, an actual textile about 3200 years old was found associated with the clay object. The textile is rectangular in shape and fits the size of the opening of the portable shrine. It was already suggested by the excavator that this textile functioned as a Parokhet (Mariette 1880, p. 551).

Figure 2.

Clay portable shrine of the goldsmith Sankhuher, 12th century BCE, from Abydos in Egypt (Mariette 1880, p. 555).

The tomb of Tutankhamun yielded a number of textiles, some of them found covering the coffin of the king. These were not shrouds wrapping the body but curtains that encircled the burial shrine, delineating it from the rest of the world. The moment of opening was described by the excavator: “At the opening of the doors of the shrine almost painful impressiveness of a linen pall decorated with golden rosettes which drooped above the inner shrine” (Carter and Mace 1923, p. 183). There was a huge spangled linen pall that had been draped over the inner shrines (Carter 1926, pp. 43–44). The pall was held up by wooden struts on a wooden frame that had to be dismantled to have access to the other shrines. In a similar way, a papyrus in Turin describes the plan of the tomb of Ramses IV, which was covered by a similar pall (Carter and Gardiner 1917; Carter 1933, pp. 36–37). The finds from the tomb of Tutankhamun give us a real example of a magnificent textile that separated the divine king from the outer world. In the same way, elaborate textiles hung over the doors of the Holy of Holies in temples delineate the statue of god from the rest of the world.

4. Depictions of Curtains on Egyptian Sacred Barks

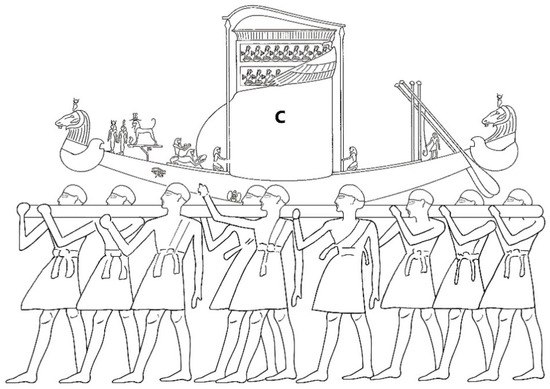

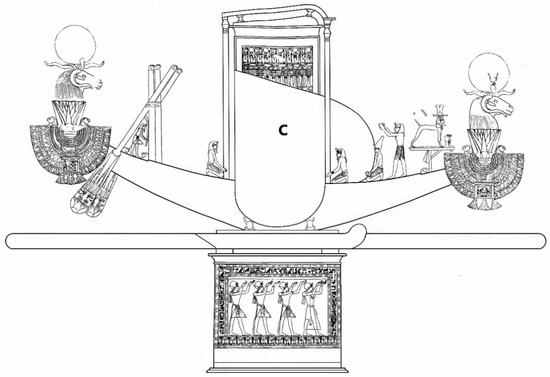

In addition to actual curtains, whether miniature or life-sized, there are numerous surviving depictions of such objects. A common motif in Egyptian scenes is a portable shrine composed of three parts: a shrine, a boat, and a base with long handles. The shrine was placed on top of the boat, while the handles were used to carry the entire installation. The term commonly used for these objects is “sacred bark” (Karlshausen 1995; Falk 2015; Noegel 2015). The door of the shrine was partly covered with a white curtain. In some depictions the top of the curtain is held by a falcon and its lower part is wrapped around the base of the shrine (Karlshausen 1995; Falk 2015, p. 190). The bark had a role in ceremonies of two different types:

- Cultic processions, when it was taken out of a temple during festivals. In this context, it was carried by a number of priests. A nice example at Karnak from the Red Chapel of Queen Hatshepsut depicts a bark of Amon (Figure 3; Lacau and Chevrier 1977; Karlshausen 1995, pp. 121–22).

Figure 3. Depiction of a sacred bark carried in a religious festival from Karnak, dated to the reign of Queen Hatshepsut, 14th century BCE (Lacau and Chevrier 1977). A large portable shrine is located on top of a boat, with its door partly covered by a white curtain (marked C). Part of the curtain flutters to the left.

Figure 3. Depiction of a sacred bark carried in a religious festival from Karnak, dated to the reign of Queen Hatshepsut, 14th century BCE (Lacau and Chevrier 1977). A large portable shrine is located on top of a boat, with its door partly covered by a white curtain (marked C). Part of the curtain flutters to the left. - Mortuary ceremonies, when it was laid on a dead king’s sarcophagus and shrine. In this context, the scene is depicted without people. In the chapel of Amen-Re in the temple of Seti in Abydos, numerous barks were depicted, each with a white curtain covering part of the shrine (see, for example, Figure 4; Gardiner 1935, Pl. 5).

Figure 4. Depiction of a sacred bark laid on the sarcophagus of Pharaoh Seti I, from the chapel of Amen-Re in the Seti temple in Abydos, dated to the 13th century BCE (Gardiner 1935, Pl. 5). A large portable shrine is located on top of a boat, with its door partly covered by a white curtain (marked C). Part of the curtain flutters to the right.

Figure 4. Depiction of a sacred bark laid on the sarcophagus of Pharaoh Seti I, from the chapel of Amen-Re in the Seti temple in Abydos, dated to the 13th century BCE (Gardiner 1935, Pl. 5). A large portable shrine is located on top of a boat, with its door partly covered by a white curtain (marked C). Part of the curtain flutters to the right.

In both contexts, the depiction of the bark is similar, with a white curtain hung from above the opening and creating an additional barrier between the statue of the god and the rest of the world. The popularity of this motif in New Kingdom Egypt (15th to 12th centuries BCE) may indicate an influence from western Asia at a time when Egypt controlled the Canaanite city states of the Levant; such influences have been identified in other aspects of Egyptian cult (Giveon 1978).

5. Sacred Curtains Depicted on Portable Shrines

We will now return to the portable shrines of clay from the ancient Near East and examine whether a curtain can be identified on some of them. It is possible that in some portable shrines an actual textile was hung from above the door, as in the Egyptian example from Abydos mentioned above. If so, close examination of the artifacts may reveal physical suspension points. Here, however, our analysis is an iconographic one. When dealing with the way a sacred curtain may be depicted, we need to take into consideration a number of methodological issues:

- Location on the portable shrine: in real life, the textile was hung above the entrance to the Holy of Holies and covered the entrance. On the portable shrines a representation of a curtain should be positioned in the same location, that is above or on the sides of the entrance. Not every ribbon of clay above a door in a pottery portable shrine necessarily represents a curtain, however. In some cases, there is a small narrow ledge above the entrance. On the portable shrine from Kition, where the ledge is supported by two pillars, we have a real portico (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, p. 105). In other cases, the ledge is probably a cornice over the door, a horizontal molding that crowns the door and emphasizes it in relation to other parts of the building. Such cornices can be seen on portable shrines from Kamid el-Loz (Echt 1986, p. 116; Muller 2002, pp. 289, 108, Figure 96; Katz 2016, Figure 2.81), Tel Dan (Biran 1994, p. 153, Figure 112; Katz 2016, Figure 2.68), and Hazor (Bechar 2017, Figures 7.126 and 7.130:12). In other words, not every thickening above a door represents a curtain.

- State of the curtain: the door of the portable shrines is open, so that an object symbolizing a divine entity, such as a figurine, could be placed inside. It is clear, in many cases, that this opening was then closed with a door (see, for example, Muller 2016, pp. 155–58). In this situation, the curtain cannot be represented as suspended from above the door, as it would block the opening. Thus, it was necessary to show the curtain as folded away, or to find another iconographic solution. There is a paradox here: how to present both the open door and the curtain that closed it.

- Representing a textile in clay: most of the elements depicted on portable shrines, such as walls, roof, pillars, door, and beams, were made from stone, mudbrick, or wood in real buildings. These are all hard, solid materials. The curtain, on the other hand, was a flexible textile and thus had to be depicted differently from the solid architectural components. Not every rope pattern ribbon represents a textile. However, when cords and ropes are represented on pottery vessels they are relating to the vessel’s handles, as if they were inserted through them (Tadmor 1992; Garfinkel 2019). In the same way, the examples depicted on the portable shrines are all associated with the upper part of the door, and sometimes the lower part as well.

Depicting a curtain on a clay object is not a simple task. The flexible textile had to be represented schematically as folded away, yet associated with the door. Close examination of the iconography of the portable shrines known to us revealed ten examples in which a curtain can be identified. In the following the examples are organized in chronological order, six from the second millennium BCE and four from the first millennium BCE (the Iron Age). In general, the earlier portable shrines are very schematic and thus provide little information on the architecture of real temples. In the Iron Age, however, some portable shrines are much more realistic, and accordingly, the depiction of a curtain can be observed more frequently.

1. Ur. This site, located in southern Mesopotamia, was a dominant city in the region for millennia. A clay shrine of the Isin-Larsa period (early second millennium BCE) was uncovered (Woolley and Mallowan 1976, p. 221, Pl. 97; Muller 2002, p. 33, Figure 34; Katz 2016, p. 39, Figure 3.4). The façade of the object has horns on both sides of the roof and the doorway is incised with a recessed pattern. Inside the innermost recess is a rounded line, resembling a suspended textile (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.

Portable shrines with a depiction of a curtain above the door: 1. Ur, southern Iraq, early second millennium BCE (after Woolley and Mallowan 1976, Pl. 97). 2. Ugarit (after Muller 2016, Figure 117c). 3–4. Kamid el-Loz (Metzger 1993, Pls. 73, 74).

2. Ugarit. This site is located on the Mediterranean coast in Syria. Two pottery portable shrines of the Late Bronze Age have been reported from the site. Above the opening of one of them is a curly ribbon of clay, resembling a folded textile (Figure 5.2, Muller 2016, Figure 117c; Katz 2016, Figure 2.84).

3. Kamid el-Loz. This site is located in the central Levant in the Beqa‘a Valley of Lebanon. A cultic area of the Late Bronze Age with two adjoining temples yielded several portable shrines (Echt 1986, p. 116). Two clay portable shrines, dated to the 13th century BCE, had a rather similar façade. The door opening is flanked by two pillars, with an elaborate capital on top of each. Immediately above the door, but lower than the top of the pillars, is a wide, uneven band of clay. In places the edges of the clay band are wider than the rest of the band, resembling a textile dropping down (Figure 5.3 and Figure 5.4; Metzger 1993, Pls. 73, 74; Muller 2002, pp. 108–109, Figures 96 and 97; Katz 2016, Figures 2.80 and 2.81).

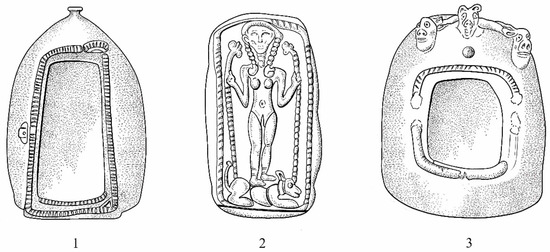

4. Tell Munbaqa. This site is located in the Euphrates Valley in Syria. A pottery portable shrine from the Late Bronze Age is decorated with an accentuated clay ribbon around the door. The entire ribbon is incised with short, straight parallel lines (Muller 2016, Figure 134b). This decoration may represent the curtain that was hung over the door in actual temples (Figure 6.1). A similar ribbon incised with short, straight parallel lines is depicted on a Late Bronze Age plaque figurine from Tel Harasim (Figure 6.2). This type of depiction appears on the portable shrine from Tel Rehov as well, but is restricted to the upper part of the opening (Figure 6.3, Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 6.

Portable shrines and plaque figurine with an incised frame around the door: 1. Tell Munbaqa (after Muller 2016, Figure 134b). 2. Tel Harasim (after Givon 2008, p. 1767). 3. Tel Rehov (after Mazar and Panitz-Cohen 2008).

This decoration is intriguing. What could be represented by short, straight parallel lines at the sides of the door of a shrine? We suggest that this decoration represents the curtain that was hung over the door. As it is impossible to show both the open shrine and the curtain closing it, the depiction gives only a hint by showing the sides of the curtain. Two different situations are commonly shown simultaneously in ancient Near Eastern art. In Assyrian war scenes, for example, the attacking army is shown in combat, while the inhabitants of the defeated city are already leaving the city through its gate (see, for example, Ussishkin 1982). We see here a similar situation, with an open door but with a hint of the curtain closing it.

5–6. Tel Harasim and Beth Shemesh. These two sites are located in the Judean Shephelah of Israel. Pottery plaque figurines dated to the Late Bronze Age, depicting a nude goddess holding a flower in each hand, have been found at both sites. At Tel Harasim the goddess stands on a lion and the entire scene is framed by a ribbon of clay incised with short, straight parallel lines (Figure 6.2; Givon 2008, p. 1767). At nearby Tel Beth Shemesh a standing nude goddess is similarly presented within a frame incised with short, straight parallel lines. This pattern has been understood as “schnurbändern” or strings, a textile product (Schroer 2011, pp. 306–307, No. 864).

In both plaque figurines, the frames are similar to the incised sides of the doors on the portable shrines from Tell Munbaqa and Tel Rehov (Figure 6.1 and Figure 6.3). The Tel Harasim and Beth Shemesh figurines represent the goddess standing in her shrine. This is an unusual presentation, as the plaque figurines usually focus on the goddess without placing her in a context (see, for example, Tadmor 1996; Kletter 2004, Figure 23.53; Weissbein et al. 2016). Later on, the Iron Age II ivories of the “woman at the window” once again represent a goddess in the context of a shrine (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, pp. 56–58).

How should we understand the imitation in clay of a textile at the sides of a shrine door? We suggest that the incised pattern around the door of the shrines represents the curtain that was hung in exactly this location. As the door is open, there is no room for the curtain and it is depicted only symbolically.

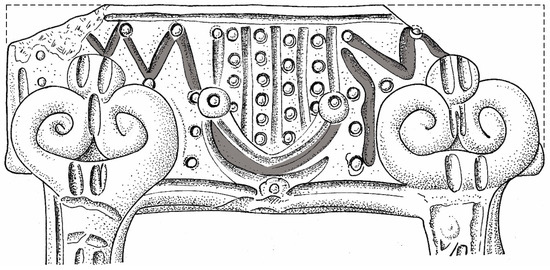

7. Khirbet Qeiyafa. This site is located in Israel, near the modern city of Beth Shemesh. Two portable shrines were found in the same room near one of the two gates of the city, one modeled in clay and the other carved in limestone (Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, pp. 111–16; 2018, pp. 83–100). The clay object represents the façade of a temple and features very detailed decoration, including two lions and two pillars, one on each side of the door. The area near the roof is emphasized by five adjacent bands of clay. The three lower bands are simple and show no decoration or mark of any kind, perhaps representing roof beams. The fourth band above the doorway shows a spiral design, formed by the potter twisting up a roll of clay and attaching it to the structure (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Clay portable shrine from Khirbet Qeiyafa, Israel, early 10th century BCE (photograph by G. Laron).

Figure 8.

Close-up of the upper façade above the door of the clay portable shrine from Khirbet Qeiyafa (photograph by G. Laron). The twisted band probably represents a rolled textile that was hung from above the door.

In our opinion, the twisted band represents a piece of rolled cloth. If so, we have here a depiction of the curtain that hung in front of the doorway and could be rolled up to leave the doorway open.

8. Tel Rehov. This site is located in the southern Levant, in the Jordan Valley, near the city of Beth Shean in Israel. A rich collection of cultic paraphernalia from the 9th–8th centuries BCE unearthed here includes a pottery portable shrine (Mazar and Panitz-Cohen 2008). The top of this object is decorated with three applied figures. The door is emphasized by a ribbon of clay, whose upper part was systematically incised with short, parallel lines, while the lower part of the ribbon was left plain. This decoration, and its position only above the upper part of the door, seems to indicate a folded curtain (Figure 5.3, Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Pottery portable shrine from Tel Rehov, Israel, dated to the 9th century BCE (courtesy of Amihai Mazar, photograph by D. Harris).

Figure 10.

Close-up of the clay ribbon above the door of the portable shrine from Tel Rehov (courtesy of Amihai Mazar, photograph by D. Harris).

9. Tell el-Far‘ah (North). This site is located in the southern Levant, in the Samaria hills near Nablus. Cultic activities took place in the gate piazza at the site, as attested by the presence of a standing stone (massebah) and a large basin. In an adjacent building an elaborate portable shrine, dated to the 9th–8th centuries BCE, was excavated (Chambon 1984, pp. 25, 77–78, Figure 66; Muller 2002, pp. 340–42; Mumcuoglu and Garfinkel 2020). Various interpretations have been proposed for its elaborately decorated façade (Chambon 1984, p. 77; Bretschneider 1991, p. 129; Keel 1998, p. 42; Zevit 2001, p. 337; Muller 2002, p. 54; Albertz and Schmitt 2012, p. 95, Figure 3.16; Katz 2016, pp. 43−44). Our detailed iconographic analysis of the upper part of the façade points to a folded curtain hung above the door (Mumcuoglu and Garfinkel 2020, pp. 115–20). In the center of the upper part of the object are five vertical incisions, creating four vertical strips. Each of these strips is covered by rounded dots created by delicate puncturing. We propose that these strips are part of the curtain, and that the dots represent embroidery work. The additional dots would then represent the folding of the curtain attached to knobs on each side of the opening (Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13).

Figure 11.

The portable shrine from Pit 241 in Building 149 at Tell el-Far‘ah North (© RMN—Grand Palais, Musée du Louvre, les frères Chuzeville).

Figure 12.

Close-up of the upper façade of the portable shrine from Tell el-Far‘ah North (© RMN–Grand Palais, Musée du Louvre, les frères Chuzeville).

Figure 13.

Drawing of the upper part of the portable shrine from Tell el-Far‘ah North, emphasizing the folded curtain.

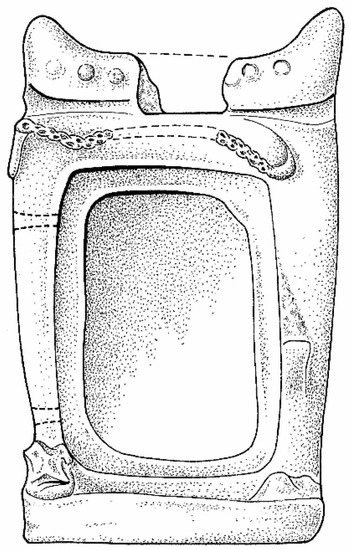

10. Tel Rekhesh. At this site, located in the southern Levant in Lower Galilee in Israel, a portable shrine was collected from the site’s surface (Bretschneider 1991, p. 237, No. 93; Zevit 2001, pp. 336–37; Muller 2002, p. 354, Figure 156; Katz 2016, pp. 65–66, Pl. 25:4; Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2015). Above the opening are the remains of an attached ribbon bearing small dense, rounded impressions. It is preserved on both the left and the right sides; on the left the end turns to the side of the item and then down for about 3 cm, while the right side turns down and then up. This “ribbon” has previously been understood as a snake (Zori 1977). However, it could represent a piece of cloth rolled up above the opening of the shrine (Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 14.

Pottery shrine model from Tel Rekhesh, northern Israel, 9th–8th centuries BCE (courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority).

Figure 15.

Front view of the Tel Rekhesh shrine model, with the accentuated clay ribbon above the door.

Figure 16.

Close-up of the upper façade of the Tel Rekhesh shrine model (photograph by the authors).

There is another group of portable shrines that is said to have originated “near Mount Nebo” in Jordan (Weinberg 1978, pp. 31–32, Figures 1–3; Muller 2002, p. 199, Figure 178; Katz 2016, Figures 3.38–3.42 and 3.45). Petrographic analysis, however, has shown that they were made from clay from other locations, such as Lebanon (Katz 2016, pp. 60–61). Based on their typology, they all date from the Iron Age II. Some of the items in this group are elaborately painted with alternating squares and parallel lines (Katz 2016, Figures 3.41 and 3.45), resembling patterns that characterize woven textiles. If this group is indeed authentic and not the result of forgery, we would suggest that the entire façade represents a curtain that was hung before the Holy of Holies of Levantine Iron Age temples.

6. Discussion

As we have seen above, the cultic curtain (Parokhet) has been in continuous use from the third millennium BCE in Mesopotamia until today. There is probably no other cultic object that has preserved its original function and name for almost five thousand years and in different cultures. The long survival of the original Sumerian term indicates the central importance of the Parokhet in the eyes of worshipers.

On the theological level, the curtain created a barrier between daily life and the divine entity whose symbol was placed inside the temple, shrine, or miniature portable shrine. As such, it was a means of separation between the mortal worshiper and the eternal divine power.

On the political level, the curtain separated between those who could cross it and those who were not permitted to do so. Priests, and sometimes kings, were able to cross the curtain, enter the Holy of Holies, and serve as mediators between the community and the gods. As we have seen in the letter from Ugarit, if an unauthorized person crossed the curtain, he was sentenced to death. A similar situation exists in the biblical tradition, when an unauthorized person touched the Ark of the Covenant (2 Sam 6:6–7). In this way the curtain was also a status symbol, separating between different segments of society.

As such an important item of cultic paraphernalia, one would expect the Parokhet to appear on miniature depictions of temples, such as small portable shrines. Indeed, a miniature curtain was found in association with a portable shrine in Egypt. This curtain, preserved thanks to the dry climate in the Nile Valley, indicates that similar curtains were probably common in other cases as well. In the same way, portable shrines in the sacred barks were depicted with a white curtain partly covering the door.

The representation of the curtain in clay portable shrines is problematic, as the objects are shown with an open door. It is thus possible that a miniature textile was often present. Nevertheless, a depiction of a folded curtain can sometimes be identified, as suggested in the various cases noted above. Not all the items are equally convincing, and in some cases, the phenomenon is expressed better, while in other cases it is less clear. The earliest example presented here is that from Ur, in early second millennium BCE Mesopotamia, while the other examples are from the Levant, dated to the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age II. This observation adds a previously overlooked aspect to the iconography of portable shrines.

Author Contributions

M.M. and Y.G. were equally involved in the research and writing of this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Arlette David for providing useful references on Egyptian shrines. The drawings were made by Olga Dobovsky. The text has been improved by the comments of anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albertz, Rainer, and Rudiger R. Schmitt. 2012. Family and Household Religion in Ancient Israel and the Levant. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Bechar, Shlomit. 2017. The Middle and Late Bronze Age Pottery. In Hazor VII. The 1990–2012 Excavations. The Bronze Age. Edited by Amnon Ben-Tor, Sharon Zuckerman, Shlomit Bechar and Débora Sandhaus. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 199–467. [Google Scholar]

- Biran, Avraham. 1994. Biblical Dan. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Hebrew Union College. [Google Scholar]

- Bordreuil, Pierre. 2006. Paroket et kapporet. A propos du Saint des Saints en Canaan et en Judée. In Les Espaces Syro-Mésopotamiens: Dimensions de l’Expérience Humaine au Proche-Orient Ancien. Subartu 17. Edited by Pascal Butterlin, Marc Lebeau, Jean-Yves Monchambert, Juan Luis Montero Fenollós and Béatrice Muller. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 161–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bordreuil, Pierre. 2007. Ugarit and the Bible: New Data from the House of Urtenu. In Ugarit at Seventy-Five. Edited by Lawson K. Younger, Jr. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bretschneider, Joachim. 1991. Architekturmodelle in Vorderasien und der östlichen Ägäis vom Neolithikum bis in das 1. Jahrtausend. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 229. Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker. [Google Scholar]

- CAD. 2005. Chicago Assyrian Dictionary. Chicago: Oriental Institute, Chicago: University of Chicago, vol. 12P. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Howard. 1926. The Tomb of Tut Ankh Amen. London: Cassell, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Howard. 1933. The Tomb of Tut Ankh Amen. London and Toronto: Cassell, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Howard, and Alan Gardiner. 1917. The Tomb of Ramesses IV and the Turin Plan of a Royal Tomb. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 4: 130–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Howard, and Arthur C. Mace. 1923. The Tomb of Tut Ankh Amen. London: Cassell, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chambon, Alain. 1984. Tell El-Far‘ah I: l’Âge du Fer. (Recherche sur les Civilisations 31). Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations. [Google Scholar]

- Constas, Nicholas. 2006. Symeon of Thessalonike and the Theology of the Icon Screen. In Thresholds of the Sacred: Architectural, Art Historical, Liturgical, and Theological Perspectives on Religious Screens. Edited by Sharon E. J. Gerstel. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 163–83. [Google Scholar]

- De Miroschedji, Pierre. 2001. Les ‘maquettes architecturales’ palestiniennes. In Maquettes Architecturales de l’Antiquité, Actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 3–5 décembre 1998. Travaux du centre de recherche sur le Proche-Orient et la Grèce antique 17. Edited by Béatrice Muller. Paris: Diffusion De Boccard, pp. 43–85. [Google Scholar]

- Du Mesnil du Buisson, Comte Robert. 1939. Les peintures de la synagogue de Doura Europos. Roma: Pontificio Istituto Biblico. [Google Scholar]

- Echt, Rudolf. 1986. Das Hausmodell KL 81:1 und sein kulturgeschichtlicher Kontext. In Bericht über die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen in Kāmid el-Lōz 1977 bis 1981. Saarbrücker Beiträge zur Altertumskunde 36. Edited by Rolf Hachmannn. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag, pp. 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Elledge, Casey D., and Ehud Netzer. 2015. The Veils of the Second Temple: Architecture and Tradition in the Herodian Sanctuary. Eretz-Israel 32: 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, David. 2015. Egyptian Barque Shrines and the Complexity of Miniaturized Sacred Spaces. In Meaning and Logos: Proceedings of the Early Professional Interdisciplinary Conference. Edited by Erica Hugues. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars, pp. 185–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay, Uri. 2014. The kalû Priest and kalûtu Literature in Assyria. Orient 49: 115–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gane, Roy, and Jeremy Milgrom. 2003. Parōket. In Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament Vol. XII. Edited by Johannes G. Botterweck, Helmer Ringgreen and Heinz-Josef Fabry. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, Alan. 1935. The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos II: The Chapels of Amen-Re, Re-Harakhti, Ptah and King Sethos. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef. 2018. Chasing Away Lions and Weaving: The longue durée of Talmudic Gender Icons. In Sources and Interpretation in Ancient Judaism. Studies for Tal Ilan at Sixty. Edited by Meron N. Piotrkowski, Geoffrey Herman and Saskia Dönitz. Leiden: Brill, pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef. 2019. The Incised Decoration of the Yarmukian Culture. In Sha’ar Hagolan Vol. 5. Early Pyrotechnology: Ceramic and White Ware (Qedem Reports 14). Edited by Yosef Garfinkel. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University, pp. 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef, and Madeleine Mumcuoglu. 2013. Triglyphs and Recessed Doorframes on a Building Model from Khirbet Qeiyafa: New Light on Two Technical Terms in the Biblical Descriptions of Solomon’s Palace and Temple. Israel Exploration Journal 63: 135–63. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef, and Madeleine Mumcuoglu. 2015. A Shrine Model from Tel Rekhesh. Strata: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israeli Archaeological Society 33: 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef, and Madeleine Mumcuoglu. 2016. Solomon’s Temple and Palace: New Archaeological Discoveries. Jerusalem: Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem and Biblical Archaeology Society. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Yosef, and Madeleine Mumcuoglu. 2018. An Elaborate Clay Portable Shrine. In Khirbet Qeiyafa Vol. 4, Excavation Report 2009–2013: Art, Cult and Epigraphy. Edited by Yosef Garfinkel, Saar Ganor and Michael G. Hasel. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- George, Andrew. 1992. Babylonian Topographical Texts. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 40. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Gespa, Salvatore. 2018. Textiles in the Neo Assyrian Empire: A Study of Terminology. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Giveon, Raphael. 1978. The Impact of Egypt on Canaan: Iconographical and Related Studies. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 20. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Givon, Shmuel. 2008. Harasim, Tel. In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Edited by Ephraim Stern. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, vol. 5, pp. 1766–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner, Daniel M. 2006. The Veil of the Temple in History and Legend. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 49: 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, Tal. 2017. The Plundering of the Temple Utensils. In Josephus and the Rabbis. Edited by Tal Ilan and Vered Noam. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, pp. 822–33. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Karlshausen, Christina. 1995. L’évolution de la barque processionnelle d’Amon à la 18e Dynastie. Revue d’Egyptologie 46: 119–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Hava. 2016. Portable Shrine Models. Ancient Architectural Clay Models from the Levant. BAR International Series 2791; Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, Othmar. 1998. Goddesses and Trees, New Moon and Yahweh: Ancient Near Eastern Art and the Hebrew Bible. JSOT Supplement 261. Sheffield: Sheffield University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz. 2004. Clay Figurines. In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish: Vol. III. Edited by David Ussishkin. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, pp. 1572–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz, Irit Ziffer, and Wolfgang Zwickel. 2010. Yavneh I: The Excavation of the ‘Temple Hill’ Repository Pit and the Cult Stands. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Series Archaeologica 30; Fribourg: Academic Press. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Kraeling, Carl-Hermann. 1979. The Synagogue. Excavations at Dura Europos Final Report VII. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lacau, Pierre, and Henri Chevrier. 1977. Une chapelle d’Hatshepsout à Karnak. Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lidov, Alexei. 2014. The Temple Veil as a Spatial Icon. Revealing an Image-Paradigm of Medieval Iconography and Hierotopy. Ikon 7: 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariette, Auguste. 1880. Catalogue Général des Monuments d’Abydos Découverts Pendant les Fouilles de Cette Ville. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. [Google Scholar]

- May, Natalie N. 2013. Gates and their Functions in Mesopotamia and Ancient Israel. In The Fabric of Cities: Aspects of Urbanism, Urban Topography and Society in Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome. Edited by Natalie N. May and Ulrike Steinert. Leiden: Brill, pp. 77–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 1980. Excavations at Tell Qasile Vol. 1. The Philistine Sanctuary: Architecture and Cult Objects. Qedem 12. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai, and Nava Panitz-Cohen. 2008. To What God? Altars and a House Shrine from Tel Rehov Puzzle Archaeologists. Biblical Archaeology Review 34: 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Megahed, Ibrahim, and Hussein Bassir. 2015. The Clay Naos of the Goldsmith Sankhuher in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Cahiers caribéens d’Egyptologie 19–20: 143–60. [Google Scholar]

- Menzel, Brigitte. 1981. Assyrische Tempel. Untersuchungen zu Kult, Administration und Personal. Studia Pohl, Series Maior 10; Rome: Pontifical Institute Press. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Martin. 1993. Kamid el-Loz VIII. Die Spätbronzezeitlichen Tempelanlagen. Die Kleinfunde. Bonn: R. Habelt. [Google Scholar]

- Moscati, Sabatino. 1988. The Phoenicians. Milan: Bompiani. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Béatrice. 2002. Les “maquettes architecturales” du Proche Orient ancien. Mésopotamie, Syrie, Palestine du IIIe au milieu du 1er millénaire av. J.-C. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 160. Beirut: Institut français d’archéologie du Proche-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Béatrice. 2016. Maquettes Antiques d’Orient de L’image D’architecture au Symbole. Paris: Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Mumcuoglu, Madeleine, and Yosef Garfinkel. 2020. Gate Piazza and Cult at Iron Age IIA at Tell el-Far‘ah North. Revue Biblique 127: 105–29. [Google Scholar]

- Noegel, Scott B. 2015. The Egyptian Origin of the Ark of the Covenant. In Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective. Text, Archaeology, Culture, and Geoscience. Edited by Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider and William H. C. Propp. Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 223–42. [Google Scholar]

- Roeder, Günther. 1914. Catalogue Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes. Leipzig: Breitkopf and Härtel. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal-Heginbottom, Renate. 2009. The Curtain (parochet) in Jewish and Samaritan Synagogues. In Clothing the House. Furnishing Textiles of the 1rst Millennium AD from Egypt and Neighbouring Countries, Proceedings of the 5th Conference of the Research Group ‘Textiles from the Nile Valley’ Antwerp, 6–7 October 2007. Edited by Antoine De Moor, Cäcilia Fluck and Susanne Martinssen-von Falck. Tielt: Lannoo, pp. 155–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Alan. 1940. The Four Canaanite Temples of Beth-Shan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schattner-Rieser, Ursula. 2012. Les empreintes bibliques et emprunts Juifs dans la culture éthiopienne. Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 64: 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schroer, Silvia. 2011. Die Ikonographie Palästinas/Israels und der Alte Orient, Vol. 3: Die Spätbronzezeit. Fribourg: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stager, E. Lawrence. 2008. The Canaanite Silver Calf. In Ashkelon 1. Introduction and Overview (1985–2006). Edited by Lawrence E. Stager, David J. Schloen and Daniel M. Master. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 577–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tadmor, Miriam. 1992. On Lids and Rope in the Early Bronze and Chalcolithic Periods. Eretz-Israel 22: 82–91. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Tadmor, Miriam. 1996. Plaque Figurines of Recumbent Women—Use and Meaning. Eretz-Israel 25: 290–96. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Ussishkin, David. 1982. The Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meulen, Faber. 1985. One or Two Veils in Front of the Holy of Holies? Theologia Evangelica 18: 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Villard, Pierre. 2010. Les textiles Néo-Assyriens et leurs couleurs. In Textile Terminologies in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean from the Third to the First Millennia BC. Edited by Cécile Michel and Marie-Louise Nosch. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 388–99. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, Saul. 1978. A Moabite Shrine Group. Muse: Annual of the Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri–Columbia 12: 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Weissbein, Itamar, Yosef Garfinkel, Michael G. Hasel, and Martin G. Klingbeil. 2016. Goddesses from Canaanite Lachish. Strata: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israeli Archaeological Society 34: 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, Leonard, and Max Mallowan. 1976. The Old Babylonian Period. Ur Excavations 7. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Yadin, Yigael. 1983. The Temple Scroll. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv, Bracha. 2019. Ceremonial Synagogue Textiles. London: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- Yon, Marguerite, and Daniel Arnaud. 2001. Etudes Ougaritiques I. Travaux 1985–1995. Ras Shamra-Ougarit XIV. Paris: Publications de la Mission Archéologique Française de Ras Shamra-Ougarit. [Google Scholar]

- Zevit, Ziony. 2001. The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Zori, Nehamia. 1977. The Land of Issachar. Archaeological Survey of Mount Gilboa and its Slopes, the Jezreel Valley and Eastern Lower Galilee. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).