Abstract

(1) Background: The role of culture in secular, spiritual, and religious coping methods is important, but needs more attention in research. The aim has been to (1) investigate the meaning-making coping methods among cancer patients in Turkey and (2) whether there were differences in two separate samples (compared to Study 2, Study 1 had a younger age group, was more educated, and grew up in a big city), (3) paying specific attention to gender, age, education, and area of residence. (2) Methods: Quantitative study using a convenience sampling in two time periods, Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57). (3) Results: In Study 2, there is a significant increase in several religious and spiritual coping strategies. Additionally, there is a positive correlation between being a woman and using more religious or spiritual coping strategies. Secular meaning-making coping strategies also increase significantly in Study 2. The results confirmed the hypotheses for gender, educational, and age differences in seeking support from religious leaders. The results also confirmed the hypotheses for gender and educational level in a punishing God reappraisal and demonic reappraisal. (4) Conclusions: As Turkey is a country at the junction of strong religiosity and deep-rooted secularism, dividing up the meaning-making coping methods into the religious and spiritual, on one hand, and the secular, on the other, reveals interesting results.

1. Introduction

The search for significance in life has, in previous approaches to meaning-making coping strategies, predominantly been sought within the framework of traditional sacred contexts, such as organized religious beliefs (Brewer et al. 2015; Braam et al. 2010; Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). However, religion is one among other resources in individuals’ orienting systems. Thus, the role of religion in the coping process is related to its role in the society at large (Ahmadi et al. 2016). When approaching coping methods, it is important to pay attention to cultural terms, whether these are expressed through traditional religious concepts or outside.

Culture affects people’s perception of illness as well as their help-seeking behavior (Kleinman 1980), and cultural knowledge, including the understanding of one’s own health or illness, is socially embodied, residing in the rules, roles, and practices of social institutions (Kirmayer and Sartorius 2007). Culture dictates the many dimensions of coping, from the kind of stressors faced to the degree of perceived stressfulness, the selection and preference of coping strategy, and the institutional resources from which one seeks help (Kanal 2019, referring to Aldwin 2007; Chun et al. 2006). Culture also plays an essential role in the choice of coping methods. In Islamic culture, Sabr (tolerance), Ekthtebar (testing), and Kader (fate or predestination) have importance for patients when coping with the psychological problems that cancer brings about, especially so where religion plays an essential role in the choice of coping methods (Aflakseir and Coleman 2011, Atighetchi 2007, Ahmadi et al. 2016). The coping process is also affected by collectivist and individualist cultures (Kanal 2019, referring to Kuo 2013). Gender differences in coping reflect social constraints (Kanal 2019, referring to Abraham and Hansson 1996) as well as family well-being over personal well-being (referring to Espin 2003). In this context, Turkey has a dominant Muslim population (99.9%), with a homogenous culture, traditional values, and a strong presence of religious institutions as well as religion in the public offices (Inglehart et al. 2014). Religion is an important aspect of life for many Turks, though attending religious services is not necessarily as common, especially among women (Inglehart et al. 2014).

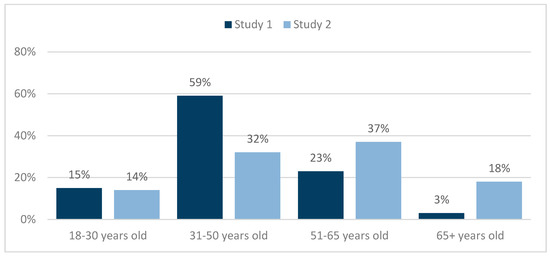

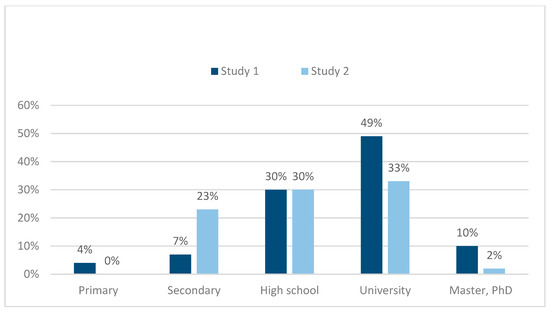

Two studies among cancer patients were conducted in Turkey (2016, here called Study 1, and 2018, here called Study 2), focusing on meaning-making coping methods. These two samples differed concerning participants’ demographics (Study 1 consisted of a younger age group, had a population with higher educational level, and, to a larger extent, grew up in a big city; see more in Figure 1 and Figure 2). In this article, we aim to present the comparison of the results from these two studies.

Figure 1.

Age groups in the sample from Study 1—Base (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

Figure 2.

Education in the sample from Study 1—Base (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

Aim

The aim in this article was to (1) investigate the meaning-making coping methods among cancer patients in Turkey and (2) whether there were differences in the samples from Study 1 and Study 2, (3) paying specific attention to gender, age, education, and area of residence. We also discuss the results within a cultural context in Turkey, considering both the Islamic and the secular dimensions.

2. Literature Review

There are not many studies focusing on the meaning-making coping in Turkey, and still fewer concerning the role of culture in coping. A qualitative interview study (Ahmadi et al. 2016) among 25 cancer patients in Turkey showed that informants used several passive and active RCOPE (Religious/Spiritual Coping) methods. Another study (Ahmadi et al. 2018b) in Turkey showed through interviewees that those who chose non-religious coping methods had still been influenced by Islamic beliefs. As the authors emphasize (Ahmadi et al. 2018b, p. 1122):

These beliefs have an obvious impact on the everyday life of Turkish people, despite the fact that the state has, until recently, played an assertive role in confining religion to the private sphere.(also referred to as laïcité)

Emotions and coping methods of Turkish parents (12 parents—eight mothers and four fathers) whose children were diagnosed with cancer were the focus of another phenomenological study (Günay and Özkan 2019). Most parents engaged in emotion-oriented coping, rather than problem-focused coping, and some parents used negative coping methods. Overcoming the first shock, parents either thought it was a false diagnosis or a test from God. All parents expressed regret about the past, and they showed anger towards the doctors, themselves, their spouses, or God.

The link between education and coping strategies has been pointed out in a study among cancer patients in Turkey, where patients with a higher level of education had higher problem-focused coping and social support scores, while lower levels of education showed more use of emotion-focused coping strategies (Tan 2007). Furthermore, in a similar study by the same author, though not statistically significant, hope was higher among male cancer patients, and denial was frequently used as a defense mechanism to reduce anxiety (Tan 2005). Higher scores for anxiety and depression among women were also found in a study among cancer patients (Karabulutlu et al. 2010; though not statistically significant for gender, this was explained by the cultural expectations for women as caregivers in Turkish society.

Problem-focused coping strategies, such as acceptance, emotional support, and religion, were the most frequently reported by patients in a survey study answered by 228 female cancer patients in Turkey (Tuncay 2014, p. 4008).

Though not related to cancer patients, a study (Karanci et al. 1999) of the 1995 post-earthquake in Turkey revealed that women reported greater distress than men. While men reported higher scores on problem-solving/optimistic coping strategies, women scored highest on fatalistic approaches, though with no significant differences. Psychosocial problems and coping strategies among Turkish women with infertility (Karaca and Unsal 2015) revealed the use of negative religious coping methods, such as seeing God’s punishment for their mistakes or God’s being unjust. However, there were also positive coping strategies, including that women will be rewarded in heaven when showing endurance.

Within an international project that has been carried out in ten different countries (Sweden, South Korea, China, Japan, Iran, Brazil, Philippines, Malaysia, Portugal, and Turkey) and with several qualitative (Ahmadi et al. 2018a; Ahmadi et al. 2018b; Ahmadi et al. 2016) and quantitative (Ahmadi et al. 2017) publications on the role of culture in the meaning-making coping used by cancer patients, this article is a follow-up on the specific Turkish material from 2016. With a cultural perspective, paying attention to contextual factors, the overall project has aimed at focusing on different forms of meaning-making coping (secular existential, spiritual, and religious) among people who have been affected by cancer in order to understand the influence of culture on the use of coping methods (Ahmadi et al. 2016).

3. Conceptual Framework: Meaning-Making Coping

In this section, we explain only the most essential concepts (for a full list of the definitions and items of religious coping methods, see Table A1 in Appendix A).

Coping: Coping is seen as a multi-layered, multi-dimensional, and contextual phenomenon that involves a number of basic skills (Lazarus and Folkman 1984, p. 148; Pargament 1997, p. 89), involving a meeting between the individual and the situation. It involves opportunities and choices, and is diverse. Another dimension of coping is that it is a process that develops and changes over time (Pargament 1997, p. 89).

Religion and spirituality: The definition of religion used is “a search for significance that unfolds within a traditional sacred context. It is then related to an organized system of belief and practice relating to a sacred source that includes individual and institutional expressions, serves a variety of purposes, and may play potentially helpful and/or harmful roles in people’s lives.” (Ahmadi 2006, p. 72). Spirituality is defined as “a search for connectedness with a sacred source that is related or not related to God or any religious holy sources” (Ahmadi 2006, pp. 72–3).

Secular existential coping: In many studies in the field of coping, the terms “religious” and “spiritual” have been used to address coping methods that are essentially based on existential issues. Nevertheless, the results of several studies (Ahmadi 2006; Ahmadi and Ahmadi 2013; Ahmadi et al. 2016; Ahmadi and Ahmadi 2018) reveal the occurrence of other coping strategies that can hardly be regarded as religious or spiritual; for instance, strategies connected to nature, to self, and to others. These kinds of coping methods can be defined as existential coping strategies, referring to a search for meaning that has no connection whatsoever to religion or religious symbols, or has an obvious connection to a sacred religious/spiritual source.

Secular existential meaning-making: Existential meaning-making is confined to those experiences that are, as explained above, outside the realm of religiosity and spirituality, but reflect a sense of belonging, significance, and meaning in individuals’ everyday lives. Referring to Ahmadi et al. (2017), the term meaning-making coping refers to the entire range of religious, spiritual, and existential coping methods. It should be mentioned that the term existential meaning-making has been used in a broader way by Lloyd (2018, p. 31). According to her:

Existential meaning-making encompasses lived experiences leading to a fundamental sense of belonging, significance, and meaning in everyday life, as well as in relation to critical events and ultimate concerns as life and death.

Secular existential meaning-making is confined to those experiences that, as explained above, are outside the realm of religiosity and spirituality, but reflect a sense of belonging, significance, and meaning in the everyday lives of individuals. Senses of belonging, significance, and meaning in the everyday lives of individuals are achieved not in a vacuum, but in an enhanced and broader context. As Reker and Wong (2012, pp. 436–7) suggest:

To achieve an enduring type of personal meaning [---] specific sources (i.e., situational meaning) need to be integrated into a larger and higher purpose (i.e., global meaning).

Culture is such a context. Marsella and Yamada (2000, p. 4) define culture as:

Shared learned meanings and behaviors that are transmitted from within a social activity context for purposes of promoting individual/societal adjustment, growth, and development. Culture has both external (i.e., artifacts, roles, activity contexts, institutions, etc.) and internal (i.e., values, beliefs, attitudes, activity contexts, patterns of consciousness, personality styles, epistemology, etc.) representations. The shared meanings and behaviors are participant to continuous change and modification in response to changing internal and external circumstances.

4. Material and Methods

The target groups for this article are two samples of cancer patients, older than 18 years. The first population, referred to as Study 1, consists of cancer patients at the American Hospital in Istanbul (n = 94). Here, a convenience sampling was used, where the questionnaire was distributed among current cancer patients during September and October 2016 using the media page of Cancer Survivors Association. The second population, referred to as Study 2, consists of patients at a specific oncology clinic in Istanbul. The study was conducted during the end of 2017 and start of 2018, during which all patients at the clinic were interviewed, using a face-to-face structured interview method and reaching a more diverse population. Both studies used a convenience sampling with different population characteristics (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

In both studies, a modified version of Pargament’s RCOPE instrument was used (Meaning, Control, Comfort/Spirituality, Intimacy/Spirituality, Life Transformation) (Pargament et al. 2000). As these authors note, the original instrument was developed to measure manifestations of religious coping and to help practitioners integrate dimensions of religiosity and spirituality in treatment. It was later developed into a Brief RCOPE (14 items). The instrument is multi-modal; it assesses how people employ religious coping methods cognitively through thoughts and attitudes. It is also multi-valent, assuming that religious coping strategies can be adaptive and maladaptive (Pargament et al. 2011). According to a meta-analysis of the Brief RCOPE, it has mainly been conducted in the United States and Western Europe using a Christian sample (Pargament et al. 2011). The authors refer to only one study among Muslim Pakistani students, which revealed Alphas of 0.75 and 0.60 for the positive and negative religious coping, respectively. The authors also refer to a study using the Brief RCOPE among immigrant populations, including Turkish, in Amsterdam, which supported the validity of positive religious coping, but not the negative religious coping. The Brief RCOPE has demonstrated good concurrent validity and incremental validity; however, predictive validity has been examined only in a limited way (Pargament et al. 2011). Earlier RCOPE studies in Turkey have shown a Cronbach’s Alpha level of 0.766 (Dicle and Ersanli 2015). The modified RCOPE used in Study 1 and Study 2 for this article had Cronbach’s Alpha values of 0.48 (low level) and 0.73 (acceptable level), respectively. The modified RCOPE instrument used in these studies had 32 items, in a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Never”) to 3 (“Always”), plus 17 background items (See Supplementary Materials).

In both studies, the questionnaires were validated for language and content by translation to Turkish and back-translation by two researchers. Possible differences were discussed until a satisfactory level of agreement was reached. Content and concepts were also adjusted to fit the Turkish cultural context, where terms such as church, priest, and God were replaced by mosque, imam, and Allah. As these studies are based on convenience sampling, we did not conduct a parametric test. Instead, to be able to account for significant differences between the two measurements, we calculated that the differences needed to be 14 percentage units or more for results around 50 percent, and more than ten percentage units for results around 10 or 90 percent. This means that the changes in behavior or attitudes between the two samples of 2016 (n = 94) and 2018 (n = 57) must be quite large to be captured with these small sample sizes. Two assumptions are guiding our analysis: The larger the sample size, the smaller the margin of error, and the curve is bell-shaped with a normal probability distribution, meaning that the margin of error becomes smaller for small and large results. For the cross-tabulations (see Table A2 in Appendix A) a T-test analysis was performed, using both years as a base (n = 151), with the independent variables of age (<45 and >45), gender (women and men), education (high school or lower and university or higher), and area of residence while growing up (big city and small city).

4.1. Hypotheses

Based on previous research on coping in Turkey, the following specific hypotheses were tested:

Hypotheses on support from religious leaders:

- H1.1: Men, who are more frequent mosque visitors, seek support from religious leaders more than women.

- H1.2: Less-educated people seek support from religious leaders more than well-educated ones.

- H1.3: Younger age groups seek help from religious leaders more than older age groups.

Hypothesis on God as a support:

- H2: Women use a passive religious deferral more than men, as women ask God to make things better to a stronger degree.

Hypotheses on a punishing God reappraisal and demonic reappraisal:

- H3.1: Men respond to a punishing God reappraisal and demonic reappraisal more than women.

- H3.2: Less-educated people use the punishing God reappraisal and demonic reappraisal coping methods more than well-educated people.

Hypothesis on area of residence and visualization:1

- H4: A big city as the area of residence while growing up has a significant effect on using more visualization.

4.2. Ethical Considerations

An application for ethical approval was sent to the Regional Ethical Board in Uppsala, Sweden, and as the study was conducted outside Sweden, the board did not have any objections to the Swedish-led part of the study (Reg. no. 2015/126). Study 1 had been approved by the American Hospital internal ethic committee and Study 2 was approved by the private clinic, where permission was given by the head of the clinic. In a short letter attached to both surveys, the respondents were informed, among other things, about the study, their possibility to withdraw, the use and preservation of data, and, if needed, the support they could receive, all according to general ethical guidelines. The respondents were also informed that they give their consent as they respond to the survey. All researchers have rich experience of conducting research among vulnerable people and are aware that, in studies dealing with sensitive information, particular consideration should be given to ethical rules. To meet the possible risks for participants being exposed to difficult emotional experiences, the participants were offered professional help if needed. However, participants expressed no such need.

4.3. Description of the Sample

The results show a difference in age distribution (see Figure 1) between Study 1 and Study 2. While the younger age group was identical in size between the two years, the 31–50 years are many more in Study 1, and the older age groups in Study 2 are older.

There was also a gender difference between the two samples, with many more men in the later study; 23% in Study 1 versus 46% in Study 2.

As seen in Figure 2, the respondents in Study 2 have a lower education. In terms of working status, very few were working in both samples: 36% and 38%, respectively, in Study 1 and Study 2. Furthermore, in both samples, it was more common to live in a relationship than not: 57% and 55%, respectively, in Study 1 and Study 2. An important difference in the sample was the place of growing up; while 77% in the Study 1 sample grew up in a big city, only 35% in Study 2 did.

5. Results

The results are presented in two parts: The religious/spiritual meaning-making coping (not thinking about one’s disease by thinking about spiritual things; seeking spiritual help from a priest or religious leader; giving spiritual support to others; do/did think that illness was caused by an evil power; feeling of a strong connection with God; experiencing a strong feeling of spirituality; feeling of a strong spiritual contact with other people) and the secular coping (thought that life is part of a greater whole; nature has been an important resource for dealing with illness; used holistic health in relation to the cancer problem; there have been alternatives to conventional treatment; regularly meditating to deal with illness; used visualization to deal with illness). It should be mentioned that the results presented here concern only those questions that were similar in both studies. Some questions, such as about the denomination and the extent of belonging, were omitted in Study 2, because after the Coup D’état in Turkey in July 2016, these questions could be sensitive to ask.

5.1. Religious and Spiritual Coping

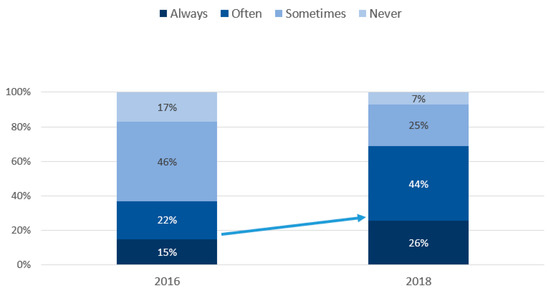

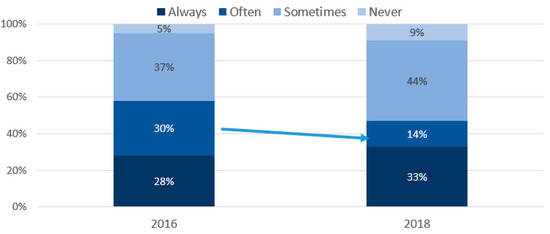

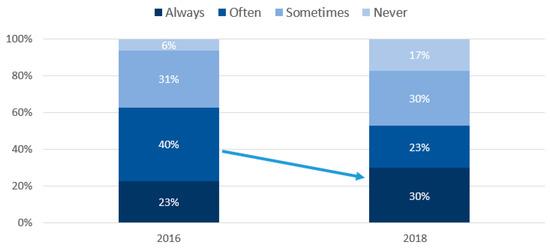

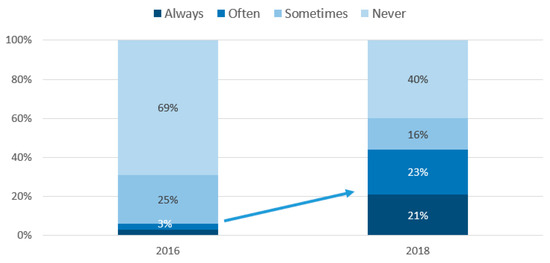

As the Figure 3 shows in Study 1, 37% of the respondents said that they always or often tried not to think about their disease by thinking about spiritual things. This increased to 70% in Study 2, which indicates a clear increase in behavior compared with Study 1. Here, a significant change between the two years is witnessed.

Figure 3.

Do/did you try not to think about your disease by thinking about spiritual things? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

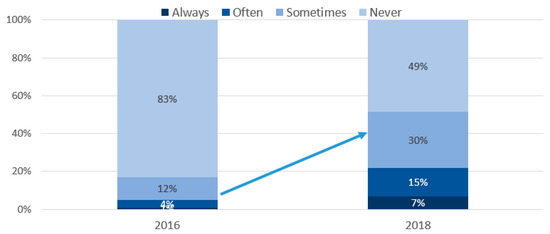

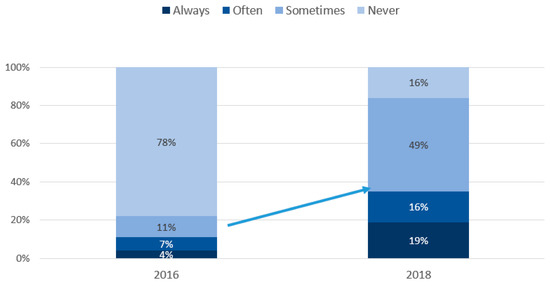

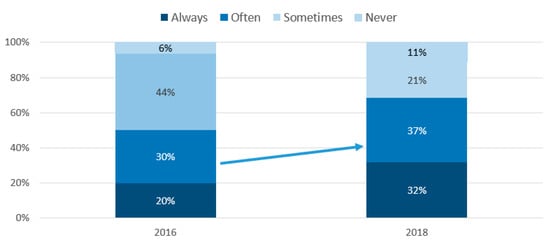

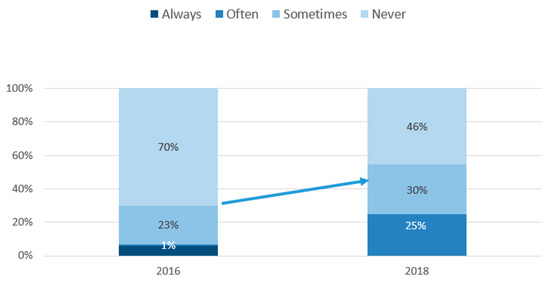

According to Figure 4, in Study 2, as many as 52% sought spiritual help from a religious leader. This is a clear significant increase compared to Study 1, where only 17% did it. To test Hypotheses 1.1, 1.2., and 1.3, we performed a cross-tabulation for the total sample, which shows that men, young persons, and those with relatively low education more often sought spiritual help from a religious leader.

Figure 4.

Have you sought spiritual help from a religious leader? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

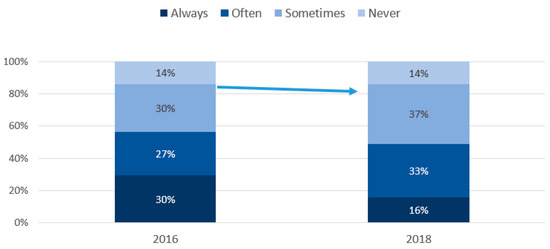

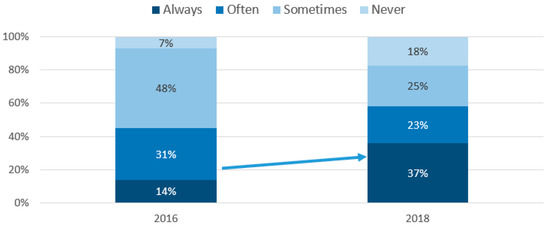

Figure 5 indicates that in Study 1, 58% answered that they gave spiritual support to others. This decreased somewhat in Study 2. In Study 2, only 47% did this, which means that it is a decrease of eleven percentage units. This is, however, a small change, and falls within the margin of error, which means that it is not significant. On the other hand, in Study 2, older age groups (<0.035), women (<0.07), and those with lower education (not significant) more often gave spiritual support to others (see Table 1).

Figure 5.

Do you give spiritual support to others? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

Table 1.

Correlation analysis for gender (women) and religious and spiritual coping resources, Study 2 (n = 57).

As Figure 6 indicates, 22% in Study 1 thought that their illness was caused by an evil power. In Study 2, this group of people increased to as much as 84%, which is a significant increase. To test Hypotheses 3.1 and 3.2, we performed a cross-tabulation, which shows that especially men and those with relatively low education, but also those who are relatively young, more often think that their illness is caused by an evil power.

Figure 6.

Do/did you think your illness was caused by an evil power? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

Figure 7 tells us that 86% reported in Study 1 that they had a feeling of a strong connection with God. The amount is the same for Study 2. The largest group answered that it happened only sometimes. The small differences in experience between the two measurements mean that there was no significant decrease from Study 1 to Study 2.

Figure 7.

Have you ever had the feeling of a strong connection with God? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

As the Figure 8 shows, almost all (93%) said that they had experienced a strong feeling of spirituality in Study 1. The amount in Study 2 was somewhat fewer: 86%. This means that there are no measured differences between the two years in having experienced this feeling, since the increase lies within the margin of error.

Figure 8.

Have you ever experienced a strong feeling of spirituality? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

Figure 9 indicates that a majority (63%) admitted in Study 1 that they always or often have had a feeling of a strong spiritual contact with other people. The percentage is somewhat lower in Study 2 (53%) but the decrease is not significant.

Figure 9.

Have you had the feeling of a strong spiritual contact with other people? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

Additionally to the comparison of the results from Study 1 and Study 2, to test Hypothesis 2, we looked more closely at the gender differences in using religious and spiritual coping resources by conducting a correlation analysis. Table 1, based on the results from Study 2, shows a positive correlation between being a woman and being more religious or spiritual on some of the variables (Pearson Correlation). This is also significant for some variables when generalizing to the whole population (Sig. two-tailed). Women experience a strong feeling of spirituality more often, they more often give spiritual support, they have more often hoped to be reborn, and they have felt more often that a spiritual force exists (all significant). However, when they are stressed, they think about God or another religious person (not significant).

5.2. Secular Meaning-Making Coping

Figure 10 reveals that, in Study 2, a majority (69%) reported that they thought always or often that their life was a part of a greater whole. This is 19% more than in Study 1. A significant increase is noticed. A cross-tabulation for the total sample shows that those living in small towns, but also women, those who are older, and those with lower education, more often think that life is part of a greater whole.

Figure 10.

Have you ever thought that your life is part of a greater whole? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

According to Figure 11, for half of the respondents (45%) in Study 1, nature has always or at least often been an important resource for them to deal with their illness. This number has increased to 60% in Study 2, which indicates a significant increase compared to the results obtained in Study 1. A cross-tabulation shows that those who are older, those with higher education, and men more often think that nature is an important resource for them to deal with their illness.

Figure 11.

Has nature been an important resource for you to deal with your illness? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

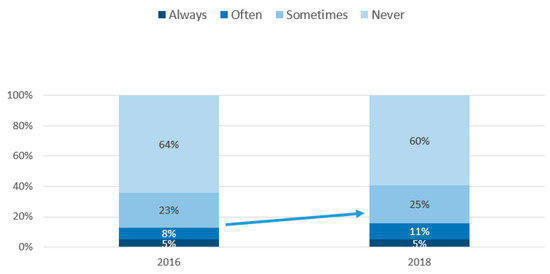

Almost half (45%) reported in Study 1 that they have used some form of holistic health in relation to their cancer problem (Figure 12). This number increased to 63% in Study 2, and the increase in comparison with Study 1 regarding this usage is significant with the current sample sizes. A cross-tabulation shows that those with lower education and those who are older more have often used some form of holistic health in relation to their cancer problem.

Figure 12.

Have you used any form of holistic health in relation to your cancer problem? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

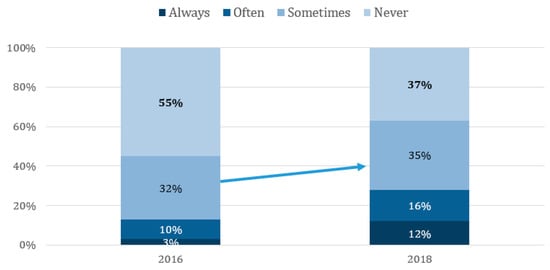

Figure 13 shows that, in Study 1, for 6% of those who reported in the previous question that they had used some form of holistic health at least sometimes, holistic health was an alternative to conventional treatment, while in Study 2, this percentage increased to 44%. The difference is significant.

Figure 13.

If at least sometimes, was there an alternative to conventional treatment? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

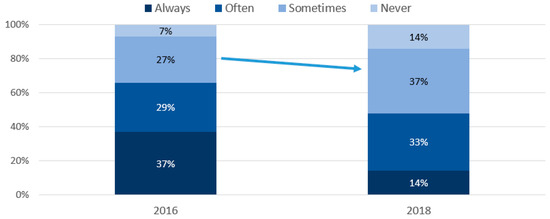

Figure 14 tells us that 30% in Study 1 regularly meditated at least sometimes for dealing with their illness. This increased to 55% in Study 2, which means that there is a significant increase in using meditation for dealing with their illness.

Figure 14.

Have you regularly meditated to deal with your illness? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

Figure 15 indicates that in Study 1, 36% answered that they at least sometimes used visualization to deal with their illness, which means that the majority had not used this method. In Study 2, a very small increase is noted (41%) but, statistically, the increase is not significant. To test Hypothesis 4, we performed a cross-tabulation, which shows that those with higher education, those who are younger, and women more often have used visualization to deal with their illness.

Figure 15.

Have you used visualization to deal with your illness? Base Study 1 (n = 94) and Study 2 (n = 57).

6. Discussion

The demographic difference between the two samples shows that the Study 2 population was more characterized by an older age group, more male dominated, with a lower education, and grew up in a rural area. Study 1 showed a low Cronbach’s Alpha value and Study 2 an acceptable level, which we found was related to two items (Study 1: “Are/were you trying to get control of your situation directly without the help of God?” and Study 2: “Pray/you asked God to make things better”) that showed negative values. We believe that the questions have been perceived differently from the others due to the formulations. When conducting a factor analysis, these two items built one factor together. All hypotheses in this article were confirmed, apart from H2 and H4.

The results confirmed H1.1—Men more than women, H1.2—Less-educated people more than well-educated ones, and H1.3—Younger age groups more than older age groups with respect to seeking help from religious leaders (see Figure 4). The result in Study 2 that men seek more support from religious leaders compared to women is in line with Study 1 (Ahmadi et al. 2017). The assumption that women in Turkey do not typically contact imams was confirmed. Based on the World Values Survey (WVS) dataset on Turkey, which indicates that men attend religious services more than women (Inglehart et al. 2014), we expected a confirmation of this hypothesis.

In the same way, the results in Study, that less-educated people seek more support from religious leaders, is in line with Study 1 (Ahmadi et al. 2017). Thus, even here, the assumption that well-educated people regard imams less as religious leaders for support holds true. It is believed that religion is more important for those with lower education than those with higher education, and also that persons with lower education find themselves as more religious (Inglehart et al. 2014). At the same time, during the last decades, a postmodern Islamic movement among young people and intellectuals has emerged in several countries, especially in the Middle East. This is partly due to an anti-imperialistic and sometimes an anti-Western attitude among people. Such a phenomenon partly caused the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Young people in Turkey face a cultural dilemma due to the strong position of Islam in Turkish society on one hand, and the long tradition of secularism on the other (Saktanber 2007).

H1.3—younger age groups seek help from religious leaders more than older age groups—was also confirmed. Given the fact that the importance of religion is more essential for the older age group, that they more often attend religious services, and that they describe themselves as being more religious (Inglehart et al. 2014), it may be surprising that the hypothesis was confirmed in that younger age groups seek help from religious leaders more often. This may be explained by the increased religious orientation in society in general, where belief in God is very strong for all age groups, from 96.3% among the younger to 98.8% among the older (Inglehart et al. 2014). In addition, bearing in mind that a higher level of education increases the problem-focused coping strategies and social support (Tan 2007), this may explain the results for the younger age group, which has both a higher education and a strong religious belief, and so uses all coping strategies available.

H2—women use a passive religious deferral more than men—was not confirmed in Study 2 (see Table 1), contrary to Study 1 (Ahmadi et al. 2017). This indicates that waiting for God to control the situation, including the ideas of being tested (Ekhtebar) and being patient (Sabr), is not affected by gender (Ahmadi et al. 2018b). This is partly contrary to the Turkish study on coping strategies after an earthquake (Karanci et al. 1999), in which the most common coping strategy among women was a fatalistic approach. The same study argues that a fatalistic approach to coping strategies needs to be culturally interpreted, assuming that if the Islamic faith is not seen as submissive, that implies that the fatalistic coping strategy is not submissive either.

H3.1—men respond to a punishing God reappraisal and demonic reappraisal more than women—was confirmed (see Figure 5). In Study 1, women responded that they never thought God caused their cancer more than men (Ahmadi et al. 2017). Other studies, though without gender comparison, have shown that women express negative coping strategies, such as seeing the issues as God’s punishment or injustice by God, as well as believing in a reward in heaven when practicing endurance. Again, a fatalist approach can result both in positive and negative coping strategies.

H3.2—less-educated people use punishing God reappraisal and demonic reappraisal coping methods more than well-educated people—was confirmed (see Figure 5). This supports the notion of the impact of education in determining superstitious ideas (Ahmadi et al. 2017), as well as the idea that less-educated people are more strongly inclined to the idea that God can determine the course of individuals’ lives and controls their deeds and destiny (Ahmadi et al. 2016). The results here highlight the need for education for increasing the positive outcomes among cancer patients. As research in the relation between education and cancer coping strategies is limited, further studies to clarify this area are needed.

H4—a big city as the area of residence while growing up has a significant effect on using more visualization—was not confirmed. In Study 1 (Ahmadi et al. 2017), it was found that respondents that grew up in a big city more often responded they always used visualization. Even in this field, the research is limited and more studies are needed.

Based on earlier research, we had not formulated any hypotheses for gender and spirituality. However, the findings revealed interesting results, where we found a positive correlation between being a woman and being more spiritual in terms of women experiencing a strong feeling of spirituality more often (<0.012), giving spiritual support more often (<0.002), hoping to be spiritually reborn more often (<0.016), and feeling that there exists a spiritual force within them more often (<0.042). Thus, for future studies, we suggest the following hypothesis: Women refer to spirituality as a religious coping resource more than men. Additionally, we had not formulated a hypothesis on gender and the coping method of pleading for direct intercession. However, based on the results in this article, where women ask God to make things better to a larger extent than men, for a future study, we suggest the following hypothesis: Women use the coping method of pleading for direct intercession more than men.

A cultural analysis for understanding coping strategies is needed, as also expressed in earlier research (Tan 2007), which shows that coping is a multidimensional concept, individual perceptions are affected by personal beliefs and values, and reducing indigenous categories of coping to common Western categories should be avoided (Kanal 2019). The Islamic coping strategies of Sabr (an active state of cooperation with God, combines the elements of acceptance and self-control), Shukr (thankfulness), Rida (contentment, satisfaction), Tawakkul (reliance on God or trust in God), Tahsin al-akhlaq (improvement of character, seeing difficulties as given to provide an opportunity to improve one’s character), and Tahdhib al-akhlāq (refinement of character) can be included in a more culture-sensitive approach to coping among Muslims (Kanal 2019, as also expressed in Ahmadi et al. 2016; Ahmadi et al. 2018b). Considering the Turkish society, Tan (2007) expresses the presence of a fatalist approach to events, with a stronger subservient approach due to religious belief. Adding to this, based on the results, we may also include the gender differences, which are possibly stronger among women. The results show that holistic health as an alternative to conventional treatment increased drastically from Study 1 to Study 2. Whether this is due to an increased religiosity or spirituality in Turkey is difficult to deduce from the results here. However, we may simply see an increased attitude in which people use both conventional medical and alternative-tradition-based treatment simultaneously, rather than one or the other.

The limitations to the representativeness and generalizability of the research results need to be mentioned. Internet users in general and patients from the American Hospital (a private hospital in Istanbul) in particular are a biased sample of the population of cancer patients in Turkey. It is very probable that individuals who are better educated, more used to internet, wealthier, or healthier took part, which is also shown in the results in Study 1 by the high level of education. The study did not use randomized sampling; thus, the results are not representative of cancer patients in Turkey in general. Even Study 2 has limitations in sampling. Though all patients during a certain period were interviewed and all had a similar fair chance to be included, the results are representative only for a certain period and for those who tend to visit clinics. Though convenience sampling was used in both studies, the results are still interesting and useful until future and more randomized studies are conducted.

7. Conclusions

Dividing up the meaning-making coping methods into religious and spiritual on one hand and secular on the other, we see some interesting differences between Study 1 and Study 2. Comparing the results of Study 1 and Study 2, we see that only the employing of four religious and spiritual meaning-making coping methods changed significantly: “Thinking about spiritual things”, “seeking spiritual help from a religious leader”, “giving spiritual support to others”, and “thinking their illness was caused by an evil power”. Regarding the secular meaning-making coping, the results indicate that five meaning-making coping methods significantly changed: “Life as part of a greater whole”, “nature as an important resource”, “use of holistic health”, “alternative to conventional treatment”, and ”regular meditation”.

As the results of this article demonstrate, the occurrence of secular meaning-making coping methods is evident. We conclude that these secular methods are linked to spiritual methods, but not to religious methods. Thus, Turkey is a good example of how religion can be an immediate means of coping among individuals for whom religion constitutes a major part of their orienting system, as well as the presence of other resources in individuals’ orientation systems. Thus, even if religion is part of the majority worldview, alternative or more traditional coping strategies may also be used in parallel.

Based on our results, we recommend both research and practical implications as follows:

- Future studies should more clearly focus on the differences among secular, religious, and spiritual coping methods, where these methods are used as independent variables.

- Caregivers shall be open for and give room for different coping methods, including secular coping methods that are meaning-making, but not necessarily religious in nature.

- Cultural competence in coping methods, including secular, religious, and spiritual, and their often positive health functions are important knowledge for all practitioners in planning and in providing care for patients.

- The cultural approach, in terms of using traditional coping strategies parallel to conventional medicine, should not be approached a priori with skepticism, as long as it is done with caution. If the alternative coping methods are discussed in the clinical treatment, the benefits may be increased, and the negative sides can be limited at the same time.

- Extending our knowledge of the importance of existential meaning-making coping may help to improve and expand efforts in social work and social care for people struggling with serious crises, especially in different societies.

Supplementary Materials

The questionnaire is available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/11/6/284/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ö.A.C. and F.A.; methodology, Ö.A.C., F.A. and P.E.; software, Ö.A.C. and F.A.; formal analysis, Ö.A.C. and F.A.; investigation, P.E.; data curation, F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Ö.A.C.; writing—review and editing, Ö.A.C. and F.A.; project administration, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of the definitions and items of religious coping methods used in this study.

Table A1.

List of the definitions and items of religious coping methods used in this study.

| A. Religious Methods of Coping to Find Meaning |

| 1. Benevolent Religious Reappraisal: redefining the stressor through religion as benevolent and potentially beneficial |

| • Tried to find a lesson from God/a Spiritual Being in the event. |

| • Tried to see how the situation could be beneficial spiritually. |

| 2. Punishing God Reappraisal: redefining the stressor as a punishment from God/a Spiritual Being for the individual’s sins |

| • Wondered whether God/a Spiritual Being was punishing me because of my lack of faith or my sins. |

| 3. Demonic Reappraisal: redefining the stressor as an act of the “Devil”/an evil power |

| • Decided the devil/evil power made this happen. |

| 4. Reappraisal of God’s Powers: redefining God’s/a Spiritual Being’s power to influence the stressful situation |

| • Realized that there were some things that even God/a Spiritual Being could not change. |

| B. Religious Methods of Coping to Gain Control |

| 1. Collaborative Religious Coping: seeking control through a partnership with God/a Spiritual Being in problem solving |

| • Worked together with God/a Spiritual Being to relieve my worries |

| 2. Active Religious Surrender: an active giving up of control to God/a Spiritual Being in coping |

| • Did my best and then turned the situation over to God/a Spiritual Being. |

| 3. Religious Deferral: passive waiting for God/a Spiritual Being to control the situation |

| • Knew I couldn’t handle the situation, so I just expected God/a Spiritual Being to take control. |

| 4. Pleading for Direct Intercession: seeking control indirectly by pleading to God/a Spiritual Being for a miracle or divine intercession |

| • Prayed for a miracle. |

| • Bargained with God/a Spiritual Being to make things better. |

| 5. Self-Directing Religious Coping: seeking control directly through individual initiative rather than help from God/a Spiritual Being |

| • Depended on my own strength without support from God/a Spiritual Being. |

| C. Religious Methods of Coping to Gain Comfort and Closeness to God |

| 1. Seeking Spiritual Support: searching for comfort and reassurance through God’s/A Spiritual Being’s love and care |

| • Sought God’s/a Spiritual Being’s love and care. |

| 2. Religious Focus: engaging in religious activities to shift focus from the stressor |

| • Thought about spiritual matters to stop thinking about my problems. |

| 3. Religious Purification: searching for spiritual cleansing through religious actions |

| • Confessed my sins. |

| • Asked forgiveness for my sins. |

| 4. Spiritual Connection: experiencing a sense of connectedness with forces that transcend the individual |

| • Looked for a stronger connection with God/a Spiritual Being. |

| • Sought a stronger spiritual connection with other people. |

| • Thought about how my life is part of a larger spiritual force. |

| • Tried to experience a stronger feeling of spirituality. |

| 5. Spiritual Discontent: expressing confusion and dissatisfaction with God’s/a Spiritual Being’s relationship to the individual in the stressful situation |

| • Wondered whether God/a Spiritual Being had abandoned me. |

| • Felt angry that God/a Spiritual Being was not there for me. |

| 6. Marking Religious Boundaries: clearly demarcating acceptable from unacceptable religious behavior and remaining within religious boundaries |

| • Avoided people who weren’t of my faith. |

| • Stayed away from false religious teachings. |

| D. Religious Methods of Coping to Gain Intimacy with Others and God |

| 1. Seeking Support from Clergy or Members: searching for comfort and reassurance through the love and care of congregation members and clergy |

| • Looked for spiritual support from clergy. |

| • Asked others to pray for me. |

| 2. Religious Helping: attempting to provide spiritual support and comfort to others |

| • Prayed for the well-being of others. |

| • Tried to give spiritual strength to others. |

| 3. Interpersonal Religious Discontent: expressing confusion and dissatisfaction with the relationship of clergy or members to the individual in the stressful situation |

| • Felt dissatisfaction with the clergy. |

| E. Religious Methods of Coping to Achieve a Life Transformation |

| 1. Seeking Religious Direction: looking to religion for assistance in finding a new direction for living when the old one may no longer be viable |

| • Asked God/a Spiritual Being to help me find a new purpose in life. |

| 2. Religious Conversion: looking to religion for a radical change in life. |

| • Looked for a total spiritual reawakening. |

| 3. Religious Forgiving: looking to religion for help in shifting from anger, hurt, and fear associated with an offense to peace |

| • Sought spiritual help to give up my resentments. |

Table A2.

Crosstabulation for coping methods by gender, age, education, and area of residence.

Table A2.

Crosstabulation for coping methods by gender, age, education, and area of residence.

| GENDER | Have you sought spiritual help from a religious leader? | Do/did you think your illness has caused by an evil power? | Have you ever thought that your life is part of a greater whole? | Have you used any form of holistic health in relation to your cancer problem? | Has nature been an important resource for you deal with your illness | Have you used for visualization to deal with your illness? | |

| Male | Mean | 1.19 | 1.31 | 1.56 | 1.21 | 1.50 | 1.05 |

| N | 42 | 42 | 41 | 42 | 42 | 42 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.40 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.22 | |

| Female | Mean | 1.10 | 1.22 | 1.62 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 1.20 |

| N | 109 | 109 | 109 | 109 | 109 | 109 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.30 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.40 | |

| Total | Mean | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.61 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 1.16 |

| N | 151 | 151 | 150 | 151 | 151 | 151 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.37 | |

| AGE | Have you sought spiritual help from a religious leader? | Do/did you think your illness has caused by an evil power? | Have you ever thought that your life is part of a greater whole? | Have you used any form of holistic health in relation to your cancer problem? | Has nature been an important resource for you deal with your illness | Have you used for visualization to deal with your illness? | |

| Younger (18–45 years) | Mean | 1.18 | 1.27 | 1.59 | 1.19 | 1.42 | 1.22 |

| N | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.42 | |

| Older (46–78 years) | Mean | 1.08 | 1.22 | 1.62 | 1.23 | 1.55 | 1.10 |

| N | 78 | 78 | 77 | 78 | 78 | 78 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.31 | |

| Total | Mean | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.61 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 1.16 |

| N | 151 | 151 | 150 | 151 | 151 | 151 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.37 | |

| EDUCATION | Have you sought spiritual help from a religious leader? | Do/did you think your illness has caused by an evil power? | Have you ever thought that your life is part of a greater whole? | Have you used any form of holistic health in relation to your cancer problem? | Has nature been an important resource for you deal with your illness | Have you used for visualization to deal with your illness? | |

| Lower education (High-school highest) | Mean | 1.16 | 1.31 | 1.61 | 1.25 | 1.46 | 1.10 |

| N | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.30 | |

| Higher education (University and above) | Mean | 1.08 | 1.17 | 1.60 | 1.17 | 1.52 | 1.23 |

| N | 71 | 71 | 70 | 71 | 71 | 71 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.42 | |

| Total | Mean | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.61 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 1.16 |

| N | 151 | 151 | 150 | 151 | 151 | 151 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.37 | |

| CITY SIZE | Have you sought spiritual help from a religious leader? | Do/did you think your illness has caused by an evil power? | Have you ever thought that your life is part of a greater whole? | Have you used any form of holistic health in relation to your cancer problem? | Has nature been an important resource for you deal with your illness | Have you used for visualization to deal with your illness? | |

| Small town | Mean | 1.18 | 1.37 | 1.68 | 1.22 | 1.54 | 1.17 |

| N | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.38 | |

| Big city | Mean | 1.08 | 1.15 | 1.55 | 1.20 | 1.45 | 1.15 |

| N | 86 | 86 | 85 | 86 | 86 | 86 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.36 | |

| Total | Mean | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.61 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 1.16 |

| N | 151 | 151 | 150 | 151 | 151 | 151 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.37 | |

References

- Aflakseir, Abdulaziz, and Peter G. Coleman. 2011. Initial Development of the Iranian Religious Coping Scale. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 1: 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Fereshteh. 2006. Culture, Religion and Spirituality in Coping; The Example of Cancer Patients in Sweden. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, Fereshteh, and Nader Ahmadi. 2013. Nature as the Most Important Coping Strategy among Cancer Patients: A Swedish Survey. Journal of Religion and Health 52: 1177–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, Fereshteh, and Nader Ahmadi. 2018. Existential Meaning-Making for Coping with Serious Illness: Studies in Secular and Religious Societies. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, Nader, Fereshteh Ahmadi, Pelin Erbil, and Önver A. Cetrez. 2016. Religious meaning-making coping in Turkey: A study among cancer patients. Illness, Crisis and Loss. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Fereshteh, Önver Cetrez, Pelin Erbil, Asli Ortak, and Nader Ahmadi. 2017. A Survey Study Among Cancer Patients in Turkey: Meaning-Making Coping. Illness, Crisis & Loss. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, Fereshteh, Mohamed Hussin, Nur Atikah, and Mohammad Taufik. 2018a. Religion, Culture and Meaning-Making Coping: A Study Among Cancer Patients in Malaysia. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, Fereshteh, Pelin Erbil, Nader Ahmadi, and Önver Cetrez. 2018b. Religion, Culture and Meaning-Making Coping: A Study Among Cancer Patients in Turkey. Journal of Religion and Health, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwin, M. Carolyn. 2007. Stress, Coping, & Development: An Integrative Perspective, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atighetchi, Dariusch. 2007. Islamic Bioethics: Problems and Perspectives. New York: Springer Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, Agnes C. Schrier, Wilco C. Tuinebreijer, Aartjan T. F. Beekman, Jack J. M. Dekker, and Matty A. S. de Witc. 2010. Religious coping and depression in multicultural Amsterdam: A comparison between native Dutch citizens and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese/Antillean migrants. Journal of Affective Disorders 125: 269–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, Gayle, Sarita Robinson, Altaf Sumra, Erini Tatsi, and Nadeem Gire. 2015. The Influence of Religious Coping and Religious Social Support on Health Behaviour, Health Status and Health Attitudes in a Brittish Christian Sample. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 2225–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, Chi-Ah, Rudolf H. Moos, and Ruth C. Cronkite. 2006. Culture: A fundamental context for the stress and coping paradigm. In Handbook of Multicultural Perspectives on Stress and Coping. Edited by Paul T. P. Wong and Lilian C. J. Wong. New York: Springer, pp. 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dicle, Abdullah Nuri, and Kurtman Ersanli. 2015. Turkish Standardization and the Validity and Reliability Studies of the Cope. Asos Journal, The Journal of Academic Social Science 16: 111–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espin, Olivia. 2003. Women Crossing Boundaries: The Psychology of Immigration and the Transformations of Sexuality. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Günay, Ulviye, and Meral Özkan. 2019. Emotions and coping methods of Turkish parents of children with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 37: 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglehart, Roy, Christian Haerpfer, Alejandro C. Moreno, Christian Welzel, Ksenia Kizilova, Jaime Diez-Medrano, Marta Lagos, Pippa Norris, Eduard Ponarin, Bi Puranen, and et al., eds. 2014. World Values Survey: Round Six—Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid: JD Systems Institute. Available online: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Kanal, Marysia. 2019. The role of religion and culture in the coping process of Syrian refugee women in Turkey. Paper Presented at Unpacking the Challenges and Possibilities for Migration Governance, Panel VII—Analysing Migrants’ Public Mental Health: Citizenship, Resilience, and the Role of Religion, The RESPOND-project, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, October 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Karabulutlu, Y. Elanur, Mehmet Bilici, Kerim Cayir, Salim B. Tekin, and Eagibe Kantarci. 2010. Coping, Anxiety and Depression in Turkish Patients with Cancer. European Journal of General Medicine 7: 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, Aysel, and Gul Unsal. 2015. Psychosocial Problems and Coping Strategies among Turkish Women with Infertility. Asian Nursing Research 9: 243–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanci, A. Nuray, Nese Alkan, Bahattin Aksit, Haluk Sucuoglu, and Evren Balta. 1999. Gender differences in psychological distress, coping, social support and related variables following the 1995 Dinar/Turkey) earthquake. North American Journal of Psychology 1: 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer, Laurence. J., and Norman Sartorius. 2007. Cultural Models and Somatic Syndromes. Psychosomatic Medicine 69: 832–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinman, Arthur. J. 1980. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, S. Richard, and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, Christina. 2018. Moments of Meaning—Towards an Assessment of Protective and Risk Factors for Existential Vulnerability among Young Women with Mental Ill-Health Concerns: A Mixed Methods Project in Clinical Psychology of Religion and Existential Health. Doctoral dissertation, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Uppsala, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Marsella, Anthony J., and Ann Marie Yamada. 2000. Culture and Mental Health: An Introduction and Overview of Foundations, Concepts, and Issues. In Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health. Edited by Israel Cuéllar and Ferredy A. Paniagua. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa M. Perez. 2000. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial variation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 519–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Margaret Feuille, and Donna Burdzy. 2011. The Brief RCOPE: Current Psychometric Status of a Short Measure of Religious Coping. Religions 2: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reker, Gary T., and Paul T. R. Wong. 2012. Personal meaning in life and psychosocial adaptation in the later years. In Personality and Clinical Psychology Series. The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications. Edited by P. T. P. Wong. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 433–56. [Google Scholar]

- Saktanber, Ayse. 2007. Cultural Dilemmas of Muslim Youth: Negotiating Muslim Identities and Being Young in Turkey. Journal of Turkish Studies 8: 417–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, Kathyrn, and Fran Greenfield. 2000. Asthma Free in 21 Days: The Breakthrough Mindbody Healing Program. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Mehtap. 2005. Social Support and Hopelessness in Turkish Patients with Cancer. Cancer Nursing 28: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Mehtap. 2007. Social Support and Coping in Turkish Patients with Cancer. Cancer Nursing 30: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncay, Tarik. 2014. Coping and Quality of Life in Turkish Women Living with Ovarian Cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2005. Religiousness and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by R. F. Paloutzian and C. L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | As Shafer and Greenfield (2000) explain, visualization is the language used by the mind to communicate and make sense of the inner and outer worlds. This technique, which is also called guided imagery, is supposed to promote physical, mental, and emotional health by having the patient imagine positive images and desired outcomes of specific situations.. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).