Abstract

In the Philippines, popular belief has it that the image of the Virgen de Caysasay was fished out of the Pansipit River in 1603. Since then, many miraculous healing events, mostly involving water, have been credited to it. The prevalence of water highlights the vulnerability of physical bodies against the onslaught of environmental destruction that comes with climate change. In the Climate Links Report on Climate Change Vulnerability (2017), it was shown that the Philippines’ agricultural and water resources are already strained due to multiple factors, including susceptibility to extreme weather conditions. Using the example of the Virgen de Caysasay, this paper examines Catholic engagement with climate change, specifically the pastoral letters of the Catholic Bishop Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) pertaining to climate change and the various responses of the faithful vis-a-vis the extreme vulnerability of the different bodies of water in the Caysasay region. I argue that, in the case of the Virgen de Caysasay, the vulnerabilities of the community—of the bodies of water and of sacred spaces by virtue of them being assigned as such due to religious practices—reveal the dissonance between what the local Catholic Church imparts and communicates through its CBCP pastoral letters on the environment to the faithful community and the realities on the ground.

1. Introduction

In a landmark pastoral letter that came out in 1988, the Filipino Catholic Bishops asked, “What is happening to our beautiful land?” The question set off an exhaustive audit of the current state of the environment, and the bishops found the travesty of the beautiful land “sinful”. In the letter, they outlined several concrete steps for the faithful to be able to materialize what their faith demands: the renewal of the land towards what God had originally envisioned when God created the world.

While the anti-mining campaigns that started in the 1970s have had some success, many environmental issues, which are undoubtedly exacerbated by climate change, still pose some challenges to the adequacy of the Catholic response. The Philippines’ extreme vulnerability to climate change, which is worsened by rapid urbanization and relentless wealth extraction from its natural resources, is well documented by scientific research. According to the World Health Organization, about 2% of the country’s GDP is lost because of the tremendous effects of the climate on the nation’s economy. This means that the Philippines is having a hard time achieving the United Nations Millennium Development Goals.

How does the case of the Virgen de Caysasay manifest the dissonance between the Catholic Bishop Conference of the Philippines (CBCP)’s pastoral letters on the environment and the vulnerable state of the bodies of water associated with her? What do these incongruities reveal about the Philippine Catholic Church’s engagement with climate change?

This paper is thus structured into the following sections. Section 1 and Section 2 present the main arguments of the paper. Section 3 presents the concrete responses of the Catholic community to the pastoral letters of the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) on climate change in the form of several initiatives, such as advocacy campaigns, mobilization, capacity building, and direct action. This section presents the positive impact, as well as the limitations, of both pastoral letters and responses, especially concerning climate change. Section 4 examines the root causes of the dissonance by presenting the case of the Virgen de Caysasay’s watery regions. Section 5 and Section 6 present the discussion and conclusions of the paper.

In this paper, I argue that, in the case of the Virgen de Caysasay, the vulnerabilities of the community—of the bodies of water and of sacred spaces by virtue of them being assigned as such due to religious practices—reveal the dissonance between what the local Catholic Church imparts and communicates through its CBCP pastoral letters on the environment to the faithful community and the realities on the ground.

Moreover, the vulnerabilities of the watery regions of the Virgen de Caysasay are symptomatic of the general lack of appreciation by the majority of Filipino people, who are Catholics, of the symbolic power of icons associated with the natural world in the Philippines. Devotional practices that include praying the novenas, going to mass, and joining the fluvial parade, among others, are anchored on a substantial belief in supernatural beings, but such belief does not flow into convictions and resulting actions that extend into public spaces such as the care for rivers, canals, lakes, and seas in a sustained manner.

This paper aims to be a part of a bigger project of locating religion in physical spaces and places, putting the spotlight on the value of the world and its physical attributes, contents, and contours and how that contributes to the meaning-making tasks of people in the context of religion. The geographical task of mapping the contours of religion is ongoing and expanding (Knott 2010), particularly in spaces that are deemed to be conventionally secular or non-sacred. In philosophy, the task involves discerning the real properties of the thing or phenomenon to examine it for itself: “We see the things themselves; the world’s what we see” (Merleau-Ponty 1962 p. 3). This “seeing” takes into account the world’s present condition—the way that it presents itself to us in the here and now. The here and now is characterized by the tremendous changes to the Earth that are brought about by climate change and many social and economic inequalities in the world.

2. The Earth as the Common Home

Since its publication in 2015, Laudato Si has become the document to which one should refer when it comes to the Catholic response to environmental or ecological issues. The Catholic bishops of the Philippines have certainly aligned their letters, which came out in 2015, 2018, and 2019, along the lines of the Laudato Si. The same year as the publication of the papal encyclical, which primarily addresses climate change, the CBCP issued a pastoral letter, “On Climate Change: Understand, Act, Pray”, which came out in July 2015. Subsequent letters in 2019 tackled climate change within specific concerns, such as the call for ecological conversion and hope amidst climate change, respectively. Although a 2008 letter identified climate change and global warming as new threats to the environment, it did not tackle the intertwining issues in a detailed manner, unlike the aforementioned letters.

Laudato Si’s influence on the Filipino Catholic Bishops is tangible in the way that the trajectory of the notion of stewardship has changed, which was heavily criticized as anthropocentric towards a more critical look at human exceptionalism. Laudato Si has become a model of doing theology that is engaged with the scientific community, the faithful, and the nonhuman members of the biotic community. It has expertly woven the scientific data to pitch for just anthropocentrism, framed in the phrase, “care for our common home”, which takes into account the Earth as a common home and not just a space to have dominion over.

Over several decades, global scientists have documented the devastating effects and the continuing threats of climate change. In several reports, these scientists have pointed to human actions as the major contributor to global warming, which brought about the climate change crisis. Climate change is an anthropogenic (human-made) intervention on Earth, caused by carbon emission from burning fossil fuels, such as coal, oil, and gas (IPCC 2012, p. 17 in Canceran 2018, p. 5).

From a theological-social-ecological point of view, not all humans are equally accountable for the ill effects of global warming; some individuals and persons should be held more accountable for the damage done, and therefore, more morally obliged to make amends. Moreover, large human communities especially those that are dependent on the natural world for their survival, live intimately and symbiotically among all members of the Earth, our common home.

The call for ecological conversion must include restitution. The social justice angle in climate change talks, mitigations, and actions must not be sidelined. Already, calls for immediate actions on the climate change crisis are being made most urgently by the young people on Earth whose precarious and uncertain future must be brought to the front and center of discussions. It is worth noting that the rallying cry is not only about the future of humans, but about the future of the entire biotic community as well.

3. The Resonance of the Pastoral Letters with the Catholic Community

This section discusses the myriad of responses of the Catholic faithful in the Philippines, which are based primarily on news articles, press releases, and journal articles that are obtainable from the internet.

Before the 1988 pastoral letter, in some dioceses in areas where extensive mining by large corporations was underway, opposition to mining was already in place. For instance, sustained anti-mining resistance by the Diocese of Malolos in the Bulacan Province took shape in the 1970s (Eballo 2018).

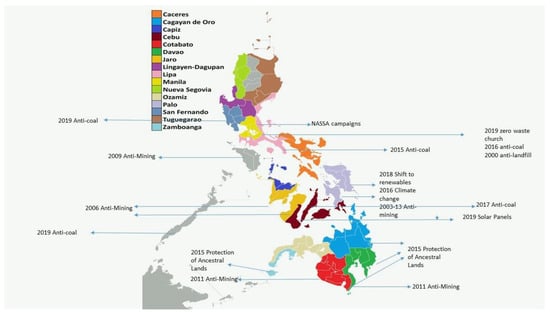

The ill-effects of large-scale extractive mining on the environment cannot be overstated enough. Large-scale mining in the Philippines has devastated entire forests, leveled off mountains, and polluted rivers and lakes with mine tailings and chemical wastes. Moreover, these activities were taking place in poor communities where several ethnolinguistic groups live. Figure 1 is a map of environmental campaigns as concrete responses to the CBCP pastoral letters on the environment.

Figure 1.

A map of environmental campaigns as concrete responses to the Catholic Bishop Conference of the Philippines (CBCP)’s pastoral letters on the environment. Original image from Howard the Duck (2013) distributed under license CC BY-SA 3.0.

By 2015, numerous reports from various international agencies were coming in about the devastating effects of global warming that were making drastic changes in the climate. The people of the Philippines cannot forget that the world’s strongest typhoon, Haiyan in 2013, pummeled the Visayas region so hard that about 10,000 people were killed and many coastal communities in the areas that were affected were erased from the face of the Earth. It is without a doubt that this singular event affected the Catholic community.

Filipino anthropologist, Jayeel Cornelio, classified these responses as mobilization, advocacy, and capacity building (Cornelio 2018, p. 18). My documentation shows that the responses went beyond these three categories because certain responses, such as installing solar panels and initiating divestment campaigns, are examples of concrete responses that are more action oriented. Table 1 shows how dioceses and parishes concretely responded to the pastoral letters on climate change.

Table 1.

Concrete responses to pastoral letters on climate change (2015 to 2019).

On 15–19 January 2015, Pope Francis visited the Philippines. His itinerary included a visit to Leyte, a coastal province that was heavily affected by Hurricane Haiyan. The Pope held a mass on the airport tarmac of Tacloban, the capital of Southern Leyte. On 18 June 2015, the papal encyclical, Laudato Si: On Care for our Common Home, was released to the public. After 2015, the campaigns against coal intensified with more dioceses coming on board. Climate change campaigns, including advocacy and mobilization, also began in 2015 as a result of the publication of Laudato Si. Among these initiatives was the 1 Million Signature Campaign for Renewable Energy, which was initiated by the National Social Action Center (NASSA) of the Catholic Bishop Conference of the Philippines in support of the United Nations’ Climate Change Panel Conference in Paris in December 2019. With respect to this connection, I have documented seven instances of specific responses to the climate change crisis in the form of the shift to renewable energy, advocating for zero waste, and advocacy campaigns to raise awareness of climate change effects and realities. These responses, in the form of various campaigns, occurred between 2015 and 2019.

The Emergence of the Catholic Church as a Voice of the Earth

The Catholic Church in the Philippines has leveraged its considerable influence on the Filipino people through multi-pronged campaigns concerning environmental issues. Perhaps the biggest impact that the 1988 pastoral letter had was in the form of a citation by no less than Pope Francis himself. In Laudato Si, Pope Francis cites the Filipino bishops:

Who turned the wonderworld of the seas into underwater cemeteries bereft of color and life?(Francis 2015, p. 31)

Pope Francis also quoted the 1988 pastoral letter in his other encyclical, Evangelii Gaudium. In the Commonweil magazine article, “The Green Pope”, Austern Ivereigh described the pastoral letter as cri de couer or a passionate appeal from the Catholic bishops of the Philippines, who, he says, had been at the forefront of the call to action on climate change (Ivereigh 2019, p. 52).

Considering the importance of Laudato Si, these several citations are remarkable in their significance. The Pontiff cited from various pastoral letters of other Catholic bishop conferences as well. In so doing, Pope Francis solidified the universality and enormity of the problem of climate change as well as a roadmap for solutions.

Another way to assess the impact of the pastoral letters is in the way that the basic ecclesiastical communities (BECs) in the Philippines have widely interpreted one of the visions of the 2nd Plenary Council of the Philippines, “a Church is a community of disciples”, which has been interpreted to be about a spirituality of stewardship. This interpretation has enabled some BECs to incorporate environmental campaigns into their platforms of action.

In his study on the impact of the 2nd Plenary Council, specifically BECs, Ferdinand Dagmang (Dagmang 2015) noted that, consistent with the way that the ecclesiastical authorities disseminate the local Roman Catholic Church’s positions on important matters, nothing short of a nationwide campaign was felt by parish priests and lay leaders to make the 2nd Plenary Council (PCP II) shape pastoral plans and activities in all the churches in the Philippines.

In other words, the “Church of the Poor” message of the 2nd Plenary Council of the Philippines must have resonated more with the Catholic faithful in terms of concrete responses to localized environmental concerns than the pastoral letters.

4. Exploring the Dissonance: The Vulnerabilities of Caysasay Waters in the Age of Climate Change

The archipelagic character of the Philippines makes it appear as if water is plentiful and free flowing. Many Filipinos certainly think so, and it undermines their perception of the real state of waterways, rivers, lakes, and seas in the country. It has blinded them from seeing these bodies of water for what they are at present. The Catholic bishops seemed to agree: “Water is taken for granted and like all things that are taken for granted, they are never really appreciated until they become scarce. We only really know the true worth of water when the well goes dry” (CBCP 2000).

In March 2019, just a few days before the start of the dry season in the Philippines, large portions of the Metro Manila area were hit with massive water disruption. More than 10 million people reside in the country’s capital. The usual supply of potable water comes from dams that are located outside Metro Manila. The main supplier, Angat Dam, had been at a critical level since January 2019 and remains dangerously at the point of depletion due to the onset of an El Niño phase in the first few months of 2019. This event prompted a renewed interest in the public about water shortage concerns.

The Philippine government’s response to this crisis was to highlight a loan from the Chinese government to turn a massive river in the neighboring town of Infanta, Quezon, into a dam. The local indigenous group, collectively known as the Dumagat, an ethnolinguistic group in the Southern Luzon area, opposed the proposed construction of the Kaliwa Dam. According to news sources, the construction of the dam would displace 150,000 residents around the river and would pose a serious threat to fishing and farming, which are their main sources of livelihood. Moreover, the Dumagats also pointed out that the river and its immediate environs are sacred according to their beliefs and traditions. The local diocese of the Catholic Church has joined the protest against the imminent construction of the Kaliwa Dam.

Large bodies of water are often the most visible witnesses to the unabated environmental destruction in the country. Seas, rivers, and lakes that connect and drain towards either the West Philippine Sea or the Pacific Ocean separate the Philippine islands from one another.

The third largest lake in the country, which is of special focus in this paper, is the Taal Lake. The lake has a total surface area of 24,356.4 hectares. As a premier tourist destination in the Philippines, visitors flock to the lake, which is surrounded by a caldera of an ancient volcano. Taal Volcano lies in its bosom. The crater of the volcano is a small lake. The Taal Lake contains another lake.

About 190,000 people are dependent on Taal Lake for their livelihood. Fishing is the most popular source of income. Farming is also largely conducted around the lake, with its exceptional ecosystem, which forms part of the Taal Volcano Protected Landscape (TVPL). TVPL covers 12 municipalities and three cities of the province of Batangas, including the town of Taal (Mayuga 2014). On 12 January 2020, the volcano erupted and spewed ash more than a kilometer high into the air. According to reports, 23,000 people living within a seven-km radius of Taal Lake were evacuated. The ashfall emissions have affected Metro Manila, which is about 86 km away.

The protected status accorded to the lake has not prevented it from the relentless assault caused by overfishing and over-pumping. Illegal fish cages dot the surface of the lake. Moreover, the rapid encroachment of urbanization poses a looming threat to the integrity of the ecosystem.

The lake is home to a species of sardines known locally as tawilis. Officials of the Department of Agriculture and the Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) have declared that the tawilis—the only freshwater sardine in the world—is becoming scarce because of various threats (Mayuga 2014).

Scientists at the University of the Philippines in Los Banos (UPLB) claim that one of the major sources of the degeneration of Taal Lake is the sifting and congestion of the Pansipit River.

The Pansipit River is the lone conduit for water and migratory fish species that sow and swim from Taal Lake to the Balayan Bay and back. This phenomenon is crucial in maintaining the ecosystem of Taal Lake.

At present, the Pansipit River, which connects Balayan Bay and Taal Lake, is reduced to a very narrow meandering body of water, which according to experts, is now clogged with trash, fish pens, and mud. It is very hard to imagine that it was once majestic; it had been wide enough for ships to pass through (Hargrove 1991, p. 5).

4.1. Devotional Practices

South of Taal Lake and west of Pansipit River, the Shrine of the Virgen de Caysasay is a small edifice of coral stones built in the 15th Century. The image of the Virgen de Caysasay has a weathered appearance and diminutive in size. It is housed in a relatively modest shrine. The stark difference is noticeable when compared to the more significantly imposing edifices of the other Virgin Marys in the Philippines who are as equally regal as their churches.

Taal Lake (and the volcano) figures prominently in the narrative of the Virgen de Caysasay. The origin story of the Virgen is known (she was fished out of the Pansipit River) widely, and Taal Lake looms as the backdrop of the extraordinary tale of the Virgen de Caysasay. The physical spaces provide the venue for devotional practices, such as pilgrimage (the Shrine), the fluvial procession and poetry recital (Pansipit River), and washing and bathing (Sta. Lucia Wells).

Every 8th of December, the present town of Taal celebrates the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. After the afternoon mass at the Shrine, the image of the Virgen de Caysasay is paraded through several barrios around town. After the parade, the image is brought to the Pansipit River for the fluvial procession. In the course of this event, the devotees sing songs called Dalit, and fireworks are lit. The procession ends at the riverbank of Nagpuloc, whereupon the image is then brought to a waiting cart. The devotees accompany the image to the Minor Basilica of Martin de Tours, also in Taal.

The Virgen de Caysasay region also includes a spring nearby, which plays a prominent role in her story. A devotee’s pilgrimage to the Virgen de Caysasay would not be complete without a visit to what is now known as the Sta. Lucia Wells. The twin wells are located on the west side of the Shrine. One must enter a narrow, paved road towards the site. What greets the visitors is an ancient arch made of coral stone—the same material as the innermost building structure of the Shrine. A brass relief of Mary is etched on the topmost part of the arch. According to local narratives, the well marks the spot where two local women who were gathering firewood found the Virgen perched on a sampaga tree; they saw her reflection in the gurgling pool of water when they stooped down to drink. Before this discovery, the Virgen had disappeared for some time.

Devotees wash their bodies with the miraculous waters of the twin wells. The ritual involves washing one’s hair and face with water from the left well and cleansing the rest of one’s body with water from the right well. Devotees can also bring home with them some of this water for friends and loved ones who are sick or need help from the Virgen. Personal observation of the ritual includes bathing, drinking, and lighting of candles.

Unique to the devotion to the Virgen de Caysasay is a poetry performance called Luwa. In major Filipino languages, luwa refers to the act of loudly expressing something out of one’s mouth. In Luwa Para sa Birhen ng Caysasay (a poem for the Virgen de Caysasay), the poem by Domingo Landicho, a Filipino poet and a Taal native, is a celebration of the devotee’s gratitude to the Virgen (Landicho 2007). Below is an excerpt of Landicho’s luwa that I translated to English:

- Luwa Para sa Inang Birhen ng Caysasay

- Inang Birhen ng Caysasay

- Luwalhati naming tunay

- Nagkaloob ay Maykapal

- Virgin of Caysasay, our Mother

- We praise you most sincerely

- For God has given you to us

- Nag-alay sa aming buhay

- (Sa tuwa at kalungkutan.

- Naging inunan mo’y ilog

- Nang sa amin ay ihandog(Inang nagpalang tibobos

- Lagi’t laging iniirog(Pinanaligan nang lubos.

- You have offered to our lives

- In joy and sadness

- You were born of the river

- So that to us you will be a gift

- A mother whose genuine blessings

- Are always and constantly held dear by us

- Whose trust in you is complete.

- Ina ka ng karaniwan, mangingisda’t maglilinang

- Lawa, ilog, karagatan

- Ang burol at kapatagan

- Ay dagat mo’t lupang hirang.

- You are the Mother of the ordinary people

- Fisherfolks and land cultivators

- The lake, river, sea

- The hills and valleys

- The ocean and the land are your beloved.

The rich tradition of this unique oral performance speaks of the endurance of the origin story of the Virgen de Caysasay. Nevertheless, the reference to the Pansipit River as a site of her birth is noteworthy because it is a deviation from the standard account of her being “found”, which suggests that she must have originated from somewhere else. Conceptualizing the Pansipit River as her birthplace suggests her affinity to it. She is as endemic to the river as the mackerel and sardine fish varieties that make the Pansipit River their birthplace. The luwa reiterates the enduring elements of the story of the Virgen de Caysasay: she moves around, and ordinary Filipinos (fisherfolk, village girls gathering firewood) stumble upon her in places where they live and work.

4.2. The Local Catholic Church Response: Ecclesiastical Authority over Marian Devotion

On 8 September 2012, to celebrate the Vatican’s recognition of the significance of the Shrine of the Virgen de Caysasay, the then Archbishop of Lipa, Ramon Arguelles, organized the first-ever fluvial procession on Taal Lake in honor of the Virgin Mary. The event was also to highlight the importance of the lake in the cultural lives of the people of Batangas. According to the news report, Bishop Arguelles lamented the sorry state of the lake—clogged with fish pens that had become a visual reminder of the neglect of the lake (Rabe 2012).

The event, “Marian Regatta: Fluvial Procession for Peace, Family, and Life”, drew thousands of devotees. It would be held for another four years, from 2012 to 2016. However, the number of participants dwindled over time. The coverage of the annual event by major media groups in the country stopped after the first year.

Meanwhile, at the bank of the Pansipit River, an arch, which is made of concrete, bears the words, Alay kay Mahal na Birhen ng Caysasay (in English, a tribute to the Beloved Virgen de Caysasay). The annual fluvial parade begins at this part of the river. Just below the arch is a small board made of tarpaulin material that seems to be recently placed. It warns the public to not throw garbage into the Pansipit River. When I looked closer at the board, I saw a display of various logos of government agencies and local government units.

The river is the site for fluvial parades for the patron saints of the area, including the Virgen de Caysasay. During these events, the Pansipit River becomes sacred again. The fluvial parade recalls the Virgen de Caysasay’s origin story. Somehow, the past is summoned from more than 400 years ago. However, a contemporary observer can only note that such devotional practice seems pitiful because it does not transform the river at all to a more pristine condition.

In Taal, except for the pilgrimage and fluvial procession, the local authorities of the Roman Catholic Church marginally sanction all other devotional practices of ordinary devotees. According to Landicho, the luwa used to be written by the best scribes in town. At present, anyone in town can write their luwa and perform it for other devotees (Landicho 2007). The poetry performance, which used to be staged at various points of the Pansipit River fluvial procession, is now conducted inside the Shrine of the Virgen de Caysasay.

I followed a beaten path towards the Sta. Lucia Wells, and I saw the rather pitiful condition of the wells. Garbage was strewn on the side of the footpath; the creek beside the wells was dry and half-filled with plastics and other refuse. I wondered about the safety of the water from the wells. While I acknowledge that the place could well be deemed as sacred, it did not appear to be so in its current state and condition.

In the story narrated by Fr. Francisco Benguchillo, which appeared in the 1834 edition of the book, Epítome de la Historia de la aparición de Nuestra Señora de Caysasay (Synopsis of the History of the Appearance or Apparition of Our Lady of Caysasay), after a passing of time, the lush forest surrounding the village of Caysasay gave way to a bustling town. In the aftermath of change, one of the tuklong markers of the apparition of the Virgen de Caysasay was destroyed, and a chapel was established in its place. While it was being built, a drought swept through the town. The people, dying of thirst, prayed to the Virgen. The chapel stood on the banks of the salty waters of the Pansipit River, but there was not a drop to drink. When the situation was about to turn for the worse, one of the workers constructing the chapel struck a rock, and spring water came gushing out for the thirsty people of Caysasay (Benguchillo 1834, p. 21).

The above snippet in the accounts of the miracles of the Virgen de Caysasay by Fr. Benguchillo alluded to the place of water in Filipino consciousness. Water is at the center of the collective attention of the people only during periods when there is a lack of it and/or when one is sick and needs healing after everything else has failed to cure whatever illness plagues the person. This was as true in the past as it is in the present.

5. Discussion

The neglected state of Taal Lake, the Pansipit River, and the Sta. Lucia Wells does not reflect the value that the community has (supposedly) bestowed on the Virgen de Caysasay. It reveals the sense of alienation of the community from the material and concrete dimensions of the Virgen; the community’s alienation from the real significance of the Virgen’s wanderings, which, to me, points to her rootedness in the place and means to convey that she could be “encountered” in spaces and places that ordinary people inhabit; and the distance and alienation from the idea of the land and waters as sacred.

Indigenous communities of the world have always considered caves, lakes, trees, and rivers as sacred. Throughout Southeast Asia, spirits associated with smaller bodies of water, such as springs, lakes, and streams, were usually personified as female, often helpful and supportive (Andaya 2016).

Filipino scholar, Gaston Kibiten, interrogated the Catholic Church’s complicity in undermining the cultures of indigenous peoples in the Philippines (Kibiten 2018). He claims that this act of interrogating is necessary despite the history of the Catholic bishops’ public statements on respecting and protecting ancestral or indigenous lands. For Tomoku Masuzawa (Masuzawa 2005), the meaning of religion is contemporary with the enlightenment period and the idea of nationhood. In the Philippines, Christianity was introduced through colonization. These sobering truths have led to more reflections in recent years on the many ways that religion is used to sustain epistemic violence by those in power. The presence of Christianity in the Philippines is always problematic when viewed through a postcolonial lens. This is not to say that the Philippine Catholic Church has not tried to address this problematique.

In 2010, the Episcopal Commission on Indigenous Peoples issued a statement that essentially asks for forgiveness from indigenous peoples for the “historical wounds” that were inflicted in the time when “[the church] entered indigenous communities from a position of power, indifferent to their struggles and pains. We ask forgiveness for moments when we taught Christianity as a religion robed with colonial cultural superiority, instead of sharing it as a religion that calls for a relationship with God and a way of life” (Gaspar 2010). Karl Gaspar, himself a Redemptorist brother, lamented the fact that the statement, which, in theory, should be read in all parishes, has not been in many of these churches. In so doing, the platform of action in the statement is not carried out widely (Gaspar 2010).

What adds to the alienation is the Roman Catholic Church’s position with regard to Mary’s “foreign-ness”, which is demonstrated in its active support of the proliferation of the images of Mary, found in almost all corners of the Philippines, which depict her to be Caucasian, with a narrow nose and blue eyes (Peracullo 2017).

According to Filipino theologian, Ramon Echica, the devotional practices that are heavily promoted by the Catholic Church in the Philippines tend to focus on “other-worldly” concerns and are apolitical (Echica 2010, pp. 44–45 as cited in Gaspar 2017, p. 91).

In a pastoral letter on the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Catholic Bishops of the Philippines extoll the “numberless benefits” the devotion to Mary has brought to believers. The bishops acknowledge that such performances of piety help keep their faith alive but stop short of bringing about transformative actions that will benefit the greater community:

It is to be hoped, however, that it will help them also to dedicate themselves with a greater ardor to the apostolate of social justice, accepting Mary’s special role in humanity’s destiny—in the development of humanity into a community of justice and peace (CBCP 1975).

In the Philippines, the confinement of the spiritual to chapels and churches has limited the authority of the local Catholic Church to effectively translate into political actions what the people believe to be transformative actions from God or Mary or the saints to grant their prayers and wishes. In the statement above, the Catholic Bishops admit as much but rue the privatized take on faith (even in social events, such as pilgrimages or fiestas) and do not offer a way to re-orient such towards a communal or shared conviction for social transformation.

The Fifth General Conference of Latin American Bishops, or Aparecida Conference, was quite clear in its insistence that the devotional practices of the people reflect the fullness of their spiritual lives and mature faith, and such faith ought not to be reduced to mere baggage, to a collection of rules and prohibitions, to fragmented devotional practices (Latin American Episcopal Council 2007, par. 12).

What had been long considered as banal na pook or sacred space is now largely sacred in a symbolic way, or sacred only in fleeting moments, such as the annual fiesta, the Holy Week, or pilgrimages to shrines or churches. The tuklong or a makeshift altar for the image of a deity used to mark sacred sites in the country before organized religion arrived at its shores. That these tuklongs were used to mark the actual physical spaces where they were found suggests that these spaces were sacred long before the foreign missionaries would have declared them to be so by a Mary or a Cross being “found” there. Now, shrines and chapels stand in the stead of tuklongs, further alienating the community from the land and waterscapes that used to be inhabited by beings that would flit in and out of the human and more-than-human worlds. For indigenous spiritualties, the domain of the sacred is palpable. The sacred world is alive. Lily Kong equated the idea of the sacred with the attachments that people develop with a certain place, such as a temple or a church, that evokes the personal and familial histories of religious adherents, contributing to the development of personal attachments and senses of place (Kong 2001, p. 220).

There is a fascinating parallel account to the Virgen de Caysaysay when we go further south of Taal, Batangas. The Virgin of Guadalupe in Cebu is so named because she was purportedly an image of the Mexican Guadalupe. The local people of Cebu call her however as the “Virgin of the Cave” (Mojares 2002, p. 152). For Mojares, the Virgin of Guadalupe in Cebu is embedded in the indigenous tradition of an earth goddess that antedates the introduction of Christianity (Mojares 2002, p. 139). Nevertheless, the twin processes of colonization and Christianization have suppressed memories of the connections of a presence-in-a cave with the mythic past of the land (Mojares 2002, p. 151).

6. Conclusions

The emergence of the Catholic Church as a voice for the Earth is noticeable in the Philippines. This has led Tremellet to declare the Catholic Church in the Philippines to be practically the only institution Filipinos can trust to speak out against environmental and other abuses (Tremlett 2013, p. 122). Nonetheless, these efforts are only sustained because local Catholic communities, as well as progressive groups, are invested in these issues, specifically mining, deforestation, and, increasingly since 2015, climate change, because these issues impact their vulnerable communities significantly.

Despite the two pastoral letters on climate change that came out after 2015, in a recent national convention on Laudato Si and the climate emergency organized by the CBCP on 3 September 2019, the participants stressed the need to strengthen ecology-related collaborations at all levels. This means, according to the 140 participants, that the bishops and the rest of the clergy should allot a budget for the creation of an ecology task force as well as the implementation of its future projects. The bishops, priests, and religious superiors were particularly singled out by the participants as key actors for the successful implementation of the action plans that the CBCP pastoral letters on climate change have laid out. The participants hoped that they will spare more time to participate in social action initiatives.

In the case of the lived experiences of the people in the Caysasay region, the economic fallout from climate change for the vulnerable people living off of the equally vulnerable lake and river is manifested in their food and economic insecurity.

Taal Lake itself is replete with legends of buried towns and buried churches (Hargrove 1991). The origin story of the Virgen de Caysasay as “found” echoes the origin story of the Cross of Alitagtag in Bauan, a town that, along with Taal, moved further south from its original location at the banks of Taal Lake. The cross was carved out from a local wood called anubing (Hargrove 1991, p. 98). Historians claim that the anubing cross was found in 1595 at “a spiritually charged place called Dingin1 near Alitagtag on Taal’s southern shore” (Hargrove 1991, p. 91). The stories surrounding the miraculous cross involved a spring of groundwater (Ramos 2014), gushing waters (Mirano 1989), and the crossing of rivers and lakes (Hargrove 1991).

The preponderance of water images in both the anubing cross and the image of the Virgen de Caysasay is no doubt a result of the lived experiences of the people, surrounded as they were by actual lakes, rivers, and springs. Moreover, devotional practices evoke protection from natural disasters, which were undoubtedly caused by the active Taal volcano.

Taal lake, the Pansipit River, and the Sta. Lucia Wells are the actual material spaces in the origin story of the Virgen de Caysasay. The Caysasay water spaces are the living, albeit, vulnerable repositories of memory of the forgotten past when the people regarded these spaces as sites where the fusion of the physical and spiritual landscapes occurred.

The persistence of these active repositories, even in their vulnerable and diminished state, for me, highlights the connection of the material landscapes to the spiritual landscapes. The undertaking to actively remember the connection, as well as the meaning, becomes an urgent task.

A modest suggestion on my part is to invite the Catholic community in the Philippines to engage in a Celebration of a Sabbath and a Jubilee for the Environment in addition to the devotional practices that are already in place. In 2000, the Catholic Church embarked on a similar year-long celebration of Jubilee during the papacy of John Paul II, and the Catholic Bishops responded to the theme based on Jesus’ words in John 10:10: “That they may have life and have it abundantly”. The Celebration of a Sabbath and a Jubilee for the Environment is about letting the land and the waters rest from the relentless onslaught of climate change. As a response to the regular fish kills in Taal Lake and the Pansipit River, the Batangas Government declared in 2018 that it would impose seasonal closures of fishing grounds in the Batangas province for approximately a month (Pa-a 2018). It is a cry for “rest” from the fishing activities in Taal Lake and Pansipit River so that it can be healthy enough for fish to thrive. In the 2019 pastoral letter, “An Urgent Call for Ecological Conversion, Hope in the Face Of Climate Emergency” (CBCP 2019), the Catholic bishops of the Philippines implore the Catholic faithful to participate in efforts to protect and preserve our seas, oceans, and fishery resources. It remains to be seen whether the impact of this pastoral letter on some climate change-related campaigns in the Philippines is going to be significant, such as in the case of anti-mining advocacies, which the Catholic Church continues to support.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support of the Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural Theology (CWCIT) of DePaul University where she was a research fellow during the fall term of 2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Andaya, Barbara Watson. 2016. Rivers, Oceans, and Spirits: Water Cosmologies, Gender, and Religious Change in Southeast Asia. TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 4: 239–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguchillo, Francisco. 1834. Epítome de la historia de la aparición de Nuestra Señora de Caysasay (Synopsis of the History of the Appearance or Apparition of Our Lady of Caysasay. Manila: Reimpresa con Superior Licencia en Sampaloc por Cayetano de Enriquez. [Google Scholar]

- Canceran, Delfo. 2018. Climate Justice: The Cry of the Earth, the Cry of the Poor (The Case of the Yolanda/Hayain Tragedy in the Philippines). Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics 8: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP). 1975. Ang Mahal Na Birhen Mary in Philippine Life Today (Part 1). Pastoral Letter. February 2. Available online: http://cbcponline.net/ang-mahal-na-birhen-mary-in-philippine-life-today-part-1/ (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP). 2000. Water Is Life. Pastoral Letter. July 5. Available online: http://cbcponline.net/water-is-life/ (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP). 2019. An Urgent Call for Ecological Conversion, Hope in the Face of Climate Emergency. July 16. Available online: https://cbcponline.net/an-urgent-call-for-ecological-conversion-hope-in-the-face-of-climate-emergency/ (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Cornelio, Jayeel. 2018. Climate Change and the Catholic Response in the Philippines. In Religious Responses to Changing Social Environment in Southeast Asia. Edited by Mira Sonntag, Erik Schicketanz and Ferdinand Maquito. Tokyo: Atsumi International Foundation Sekiguchi Global Research Association, pp. 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dagmang, Ferdinand. 2015. From Vatican II to PCP II to BEC Too: Progressive Localization of a New State of Mind to a New State of Affairs. In Revisiting Vatican II 50 Years of Renewal Volume II: Selected Papers of the DVK International Conference on Vatican II (31 January–3 February 2013). Edited by Shaji George Kochuthara and CMI. Bangalore: Dharmaram Publications, pp. 308–26. [Google Scholar]

- Duck, Howard The. 2013. Jurisdictions of the Different Metropolitan Sees of Roman Catholic Archdioceses in the Philippines. Wikimedia Commons, the Free Media Repository. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Roman_Catholic_Archdioceses_in_the_Philippines.png&oldid=230327776 (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Eballo, Arvin. 2018. Contextualizing Laudato Si’ through People’s Organization Engagement: A Kalawakan Experience. Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics 8: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Echica, Ramon. 2010. The Political Context of the Infancy Narratives and the Apolitical Devotion to Santo Nino. Hapag 7: 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Pope. 2015. Laudato Si: Encyclical Letter of the Holy Father Francis on Care for our Common Home. Pasay City: Paulines Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, Karl. 2010. The Story Behind the Indigenous Peoples’ Sunday. MindaNews. October 7. Available online: https://www.mindanews.com/around-mindanao/2010/10/the-story-behind-the-indigenous-peoples-sunday/ (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Gaspar, Karl. 2017. Embracing the Mother’s Perpetual Compassion. In Our Mother of Perpetual Help Icon and the Filipino Spirituality: Multidisciplinary Perspectives to a Perpetual Help. Edited by Karl Gaspar and Desiree Mendoza. Quezon City: Institute for Spirituality in Asia, pp. 51–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove, Thomas. 1991. The Mysteries of Taal: A Philippine Volcano and Lake, Her Sea Life and Lost Towns. Manila: Bookmark Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC). 2012. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ivereigh, Austen. 2019. The Green Pope: Why Call It Progress? Pope Francis’s Critique of Modern Life. Commonweal Magazine 146: 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kibiten, Gaston. 2018. Laudato Si’s Call For Dialogue with Indigenous Peoples: A Cultural Insider’s Response from the Christianized Indigenous Communities of the Philippines. Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics 8: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2010. Religion, Space, and Place: The Spatial Turn in Research on Religion. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 1: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Lily. 2001. Mapping ‘New’ Geographies of Religion: Politics and Poetics in Modernity. Progress in Human Geography 25: 211–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landicho, Domingo. 2007. Ang Tradisyon Ng Loa. Tanod: Diyaryo ng Bayan. October 18. Available online: http://www.caysasay.com/Caysasay%20News/caysasayLandicho.html (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Latin American Episcopal Council. 2007. Conclusive Document Fifth Conference. Available online: https://www.celam.org/aparecida/Ingles.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Masuzawa, Tomoku. 2005. The Invention of World Religions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayuga, Jonathan. 2014. Overfishing: Save Taal Lake to Save the ‘Tawilis’. Business Mirror. February 4. Available online: https://businessmirror.com.ph/2019/02/04/save-taal-lake-to-save-the-tawilis/ (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by C. Smith. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mirano, Elena. 1989. Subli: One Dance in Four Voices. Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines. [Google Scholar]

- Mojares, Resil. 2002. Stalking the Virgin: The Genealogy of the Cebuano Virgin of Guadalupe. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 30: 138–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pa-a, Saul. 2018. Batangas to Enforce Seasonal Closure of Fishing Grounds Next Month. In Philippine News Agency; October 12. Available online: https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1050906 (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Peracullo, Jeane C. 2017. Maria Clara in the Twenty-first Century: The Uneasy Discourse between the Cult of the Virgin Mary and Filipino Women’s Lived Realities. Religious Studies and Theology 36: 139–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, Marrah Erika. 2012. A Fluvial Procession of Marian Images, Devotees in Taal Lake, Philippine Daily Inquirer, September 12. Available online: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/269398/a-fluvial-procession-of-marian-images-devotees-in-taal-lake#ixzz5ueDqOtIg (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Ramos, Michael M. 2014. Theological and Doctrinal Terms Articulated in Filipino Language: A Pedagogical Approach in Religious Studies. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences 1: 145–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tremlett, Paul Francoise. 2013. The Ancestral Sensorium and the City: Reflections on Religion, Environmentalism, and Citizenship in the Philippines. In Handbook of Contemporary Animism. Edited by Graham Harvey. Durham: Acumen, pp. 113–23. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Also known as a place of worship. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).