Abstract

This article examines one of Juana of Castile’s books of hours (London, BL Add. MS 18852) comparing it with those written for members of Juana’s family and seeking to discern how it was used, in order to reassess her peers’ evaluation of her spiritual affinities. It considers how Juana customized her book of hours with a miniature of the Virgin and Child, comparing it with a gifted panel painted by Rogier van der Weyden that Juana treasured to show how she placed herself under the protection of the Virgin. Numbered precepts would be intended for her to instruct any future children and are replicated in Isabel, her daughter’s, book. The office of the Guardian Angel is compared with similar ones in Spain and Burgundy and, like devotion to St Veronica, such prayer is another means of protection. The striking mirror of conscience with its reflected skull, like other similar objects decorated with a skull that Juana possessed, sought to lift her from the decay and sinfulness of the world to the spiritual realm.

1. Juana of Castile, a Mad Queen?

Juana of Castile, third child of Isabel (1451–1504) and Ferdinand (1452–1516), the Catholic Monarchs, was born in 1479.1 In 1496, she made a triumphal entry into Brussels to marry Philip the Handsome, Duke of Burgundy (Legaré 2011). Insights into her life in Castile can be discerned in the poetic games, which marked her send-off from Laredo (Boase 2017, vol. I). In 1500, Juana became heiress of the Kingdom of Castile on the untimely death of her older brother, Juan, and the death in childbirth of her older sister, Isabel (†1500) (Graíño 2005, pp. 1111–14). Juana and Philip left for Castile to be sworn in as legitimate heirs to the throne and for Juana to be invested as Princess of Asturias (Zalama 2010, pp. 130–60; Porras Gil 2016, p. 25). Back in the duchy, Juana was held by her husband in an unenviable state between seclusion and captivity, as Philip sought to position himself as King of Castile (Zalama 2010, pp. 170–78; Fleming 2018, pp. 86–87). Juana and Philip returned to Castile when Juana inherited the throne of Castile on the death of her mother in 1504.

History and myth have not treated Juana well, and despite becoming queen, her name has been strongly associated with her characterization as Juana the Mad (Aram 2005; Fleming 2018, p. 91).2 A re-evaluation of Juana’s history has been recently undertaken by Bethany Aram (2005), Cristina Segura Graíño (2005), and Gillian Fleming, while María A. Gómez, Santiago Juan-Navarro, and Phyllis Zatlin’s edited collection (Gómez et al. 2008) demonstrates the way various myths about her mental instability were constructed about her for political ends. Shortly after their arrival in Castile, Philip died and Juana, pregnant with her youngest child, accompanied his coffin across Castile, contributing to the construction of the legend about her as a madwoman (Zalama 2010, pp. 217–32). Juana I, Queen of Castile in name only, was confined to a palace-convent in Tordesillas. First her father, Ferdinand, King of Aragon, ruled Castile on her behalf, and when he died, her son, Charles V, continued to do so.3 Ferdinand required Juana to submit to his paternal authority, whilst taking responsibility for governing her household and her realms for her (Aram 2005, p. 91). Juana’s final years were marred by conflicting accusations of possession by the devil and witchcraft, whilst her incarceration at Tordesillas became stricter with violent constraints allegedly used (Aram 2005, pp. 152–55).4 Questions over Juana’s spirituality had surfaced during the early years of her marriage. It has been alleged that her parents were concerned enough about Juana’s spirituality to dispatch a Dominican prior, Tomás de Matienzo, to visit Brussels in 1499 and report back, although Zalama (2010, p. 115) disputes this paternal concern, considering instead that the Catholic Monarchs were more concerned about the behavior of Philip on political grounds. Her mother, Queen Isabel, cultivated herself as God’s appointed monarch, no doubt wishing Juana to do the same. Juana’s early disinclination to confess turned into downright refusal unless her servants were removed, revealing her troubled relationship with those she considered her jailers and feeding family concern about her spiritual wellbeing (Aram 2005, p. 155).5

This article examines one of Juana’s books of hours (London, BL Add. MS 18852), seeking to discern how it was used, in order to reassess her peers’ evaluation of her spiritual affinities. In order to address how Juana’s spirituality might be perceived in her book of hours, I compare it with other devotional books, including those owned by her mother and her son. I also contrast it with devotional objects she owned as, taken together with the book of hours, these point to how her spirituality developed. Numerous studies have been undertaken of BL Add. MS 18852 (Kren and McKendrick 2003, pp. 385–87, cat. no. 114; McKendrick 2003, pp. 197–99; As-Vijvers 2003).6 Too few have analyzed how it exemplifies Juana at prayer nor how she was being directed to pray by her husband and those who advised him at the ducal court.7 Juana’s devotion to the Virgin is indisputable and I discuss it with reference to various aspects of her devotions.

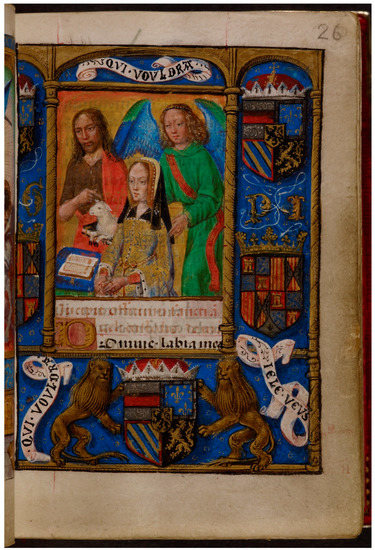

Juana’s book of hours was almost certainly given to her as a wedding gift (Reinburg 2009, p. 236). Hours were valued not only for the painted miniatures within their covers, but as a testimony to events in women’s lives (Reinburg 2009, p. 237). The hours given by Philip might have been important to her, especially after his untimely death in 1506. After all, it commemorates his motto and his coat-of-arms with the border around the first miniature of Juana commemorating her union with Philip (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 26r, Figure 1). It also recalls a time when she seemed ready to take her throne and rule. Unlike many ordinary owners of a book of hours, Juana is not dependent on the book for her historical presence (Smith 2003, p. 11) for she is depicted in many manuscripts of the time. The shields of Philip and Juana are linked by a love knot, entwined with the letters P and I (Philip and Iohanna). In the same miniature, Juana’s namesake, John the Baptist, holds the lamb, symbol of Christ slain, alongside Juana, and in so doing, promotes her role as a Christian wife. The motto of each partner is depicted in the border, together with their coat-of-arms. Heraldic details have been designated a ‘signature’ (Reinburg 2012, p. 68). The mottos, Philip’s ‘Qui vouldra’ and Juana’s ‘Je le veus’, serve the same purpose. Philip’s motto means either ‘he who will desire’ or ‘who desires it’ (Fleming 2018, p. 26). Juana’s motto means ‘I want [or desire] it [or him]’ or, in response to Philip’s motto ‘I do’ (Fleming 2018, p. 26). The futuristic element of Philip’s motto separates him and his desires from Juana’s. The joint mottos establish Philip in command of affairs, for he is the questioner. Juana’s is in second place, as she responds. Her motto ‘I want it’ began to ring with obstinacy as her life unfolded (Fleming 2018, p. 26).

Figure 1.

London, British Library, Add. MS 18852, fol. 26r. Hours of the Guardian Angel.

Tracing Juana’s prayer in this book, more than any other, gives an insight into her life as a young wife, rather than the disastrous later years of her semi-incarceration in Castile. The gifted hours were an important record of how Philip thought his wife should conduct herself. This article evaluates the additions Juana made to her hours, using these to exemplify the nature of her piety in her young married life, before any hint of madness overshadowed her. It focuses attention on her devotion to the Virgin, expressed through the prayers and miniatures in her hours. It studies the didactic section of the hours with its emphasis on obedience and the impact that was to have on Juana’s subsequent ability to counter her father’s demands.8 It evaluates the fascinating insight into confronting her own mortality through contemplating death mirrored before her. Her devotion to the Passion, exemplified in St Veronica and the vernicle, also emerges from the pages of the book of hours. Finally, it assesses the saints favored by Juana in her prayers.

Juana’s book of hours remained in her possession until her death when it was found in the inventory of her goods: ‘another tiny book in parchment in medium-sized handwriting with many miniatures and illuminations and the first miniature is of Adam and Eve and of how they were thrown out of Paradise. It begins with the mirror of conscience and has covers of crimson velvet.’9 Keeping the book of hours for over 50 years is not an indicator that Juana considered this book important because of its contents, but its presence in the inventory suggests that she valued it as a gift from her husband, as a precious object, as a prayer book, or as a combination of all the above.

2. Reading and Praying

Women’s spiritual activity depended on their literacy, for their prayer was supported by written texts. Their ability to read Latin was an essential factor in determining how they might engage with such written material. The historiography of written prayers, therefore, intersects with the rich vein of scholarship about women’s literacy and reading practice.10 Laywomen began to own books and even commission them in the later Middle Ages, as evidenced by their names inscribed in texts or from wills (Erler 2002, p. 118).11 Devout women expressed their piety precisely through book ownership (Bryan 2008, p. 11). This section examines how Juana may have used her hours from the evidence embedded in them, considering whether she wrote her own prayers and what miniatures she commissioned for her hours tells us of her devotion to the Virgin, whether she used the pictures or prayed from picture and text, and whether she prayed silently alone or aloud with others.

Juana’s hours, including the instructional section, are written entirely in Latin, even though French was the language of the court. Latin was chosen for Margaret of Cleves’s book of hours because Margaret could read Latin well (Hand 2013, pp. 80–81). The same would apply to Juana. Strict religious education, including Latin, is documented for Juana’s brother, Juan (†1497), Prince of Asturias (Alcalá and Sanz Hermida 1998), while Queen Isabel also took close interest in her daughters’ education (Aram 2005, pp. 22–30; Aram 2008; Cruz 2018, pp. 31–32). Juan Luis Vives (1492–1540) wrote in his On the Education of Christian Women (Vives 1996) of his patron, Catherine of Aragon’s (1485–1536) reputation for deeply held religious beliefs and considerable learning (Kolsky 2012, p. 15). Indeed, all Isabel’s daughters were praised for their erudition (Vives 1996, pp. 36–37). Juana was singled out for commendation of her fluency in Latin:

People in various parts of the country tell me in words of praise and admiration that Juana, wife of Philip and mother of our Emperor Charles, answered in Latin to the Latin ex tempore speeches customarily delivered in every town in the presence of new princes.12

It was certainly the case that Latin prayers, even used by those with little knowledge of Latin, were essential in making connection with the sacred performance of the liturgy, but for a woman fluent in the language they would be a means of addressing the divine (Van der Laan 2015, p. 203). The relationship between the nuns of Syon Abbey and their books of hours demonstrates how the readers saw the words on the page as ‘intermediaries between themselves and God’ (Krug 2005, p. 192). Juana, if she were devout, would have understood the book of hours as a way of conversing with God (Reinburg 2012, p. 162).13 Prayer texts were embodied or performed by their readers, for the handwritten text is a scrap of the past, ‘immobilized’, waiting for the reader to read (aloud or silently) and voice it (Zumthor and Engelhardt 1984, p. 71).14 First Juana and then other supplicants after her death embodied the prayers in the book in the quiet space heard by an unseen God.15 Yet, from the prayer books we now have, it is often nearly impossible to determine how its owner prayed (Reinburg 2009, p. 236). Whether the Latin words on the page were read or whether they simply triggered prayer, in Latin or in the vernacular, might vary from user to user.

Monastic readers ruminated on, and then dispensed with, reading the text, turning to picture-based contemplation (Green 2007, p. 75). A laywoman like Juana might employ pictures to develop contemplative prayer in a similar way (Finnegan 2013, p. 285). The visual provided support for those at the bounds of literacy (Camille 1985) but the visual richness was appreciated even by highly literate women like Juana. Devotional reading of a book of hours also beckons to lectio divina, bringing about a ‘meditative and introspective experience’ (Sterponi 2008).

Medievalists have long made the ‘unspoken assumption’ that books of hours were intended for individual use, in other words for ‘private reading and devotion’ (Coleman 2005, p. 222).16 However, care needs to be taken about assuming that they constituted private literacy (Cruse 2013). Written prayers are not just a record of how an individual prayed, for it is likely they were heard or shared by other members of the household. In any case, hours represented the Church at prayer as bells from local convents punctuated the call to pray. Time was communal and universal, sanctified, and audible (Wieck 1988; König 2012, p. 8).17 Rather than exemplifying private devotion, books of hours owned by an archduchess must have been used at court for communal and audible rather than silent prayer.

A very well-established way to determine Juana’s personal relationship with God would be through individual prayers transcribed into her book of hours (Duffy 2006a, pp. 38, 83).18 Yet Juana added none in her own hand. Although it might be assumed that Juana was not devout and, therefore, did not wish to write any prayers, this cannot be substantiated with details of whether or not she copied prayers.19 Given that her mother’s hours are not annotated with additional prayers, it is probable that adding written prayers to royal books of hours was not customary in Castile.20 Not adding prayers in her own hand might mean Juana had no need to add prayers because she was able to turn to different books for different occasions. Between them, the books she owned held all the prayers she needed.21 According to the inventory of her possessions, Juana owned 21 books of hours, each with prayers and hours arranged differently (Ferrandis 1943, pp. 220–30, [fols 64r–82]).22

Juana might not have used the book of hours to guide her prayers, perhaps because its jewel-like quality made it too valuable. It is certainly true that parts of the hours reveal little sign of soiling, indicating that certain prayers were not used often. However, even carrying the book of hours in its rich covering or chemise (Reinburg 2012, p. 78) meant she achieved a display of piety, enhanced whenever she opened the book and revealed the miniatures with their rich colors. The concept of manuscripts as sensorium is particularly applicable for richly illustrated books of hours, as is recognizing that prayer has visual, auditory, tactile, material, and musical resonances of words lifted from page to enunciation (Ong 1967; see also Finnegan 1988). Words were seen, heard, touched, and spoken. Indeed, in the performance of prayer, whether kneeling, sitting, holding the book, opening the book, letting the eye engage with a miniature, private altarpiece, or a set of words, that prayer is seen, known, public, recognized by visitors to the household, such as Prior Tomás. Walking with the book would have indicated the beginning of a prayer activity and acted as a signal of prayerfulness. Walking through the ducal palace holding her book of hours might have been enough for Juana (Walsham 2004, p. 126).23 Once the prayer destination was reached, the chamber, the chapel, the duchess’s chambers, all that remained to begin praying is to open the book. Then its pages were touched, smelt, and absorbed with the eye so that even holding or opening it would act as trigger to prayer. However, the very lavishness of the cloth covering was testimony to the value of the book (Keane 2008) and the piety of its owner (Rudy 2016, p. 333). If creating a book of hours with its treasure binding operated as an act of worship, covering and uncovering it in public also belonged to ritualized practice for sacred objects, such as unveiling a reliquary or the tabernacle, or revealing the Corpus Christi in its monstrance (Walsham 2004, p. 213). Juana’s book of hours was a tactile object and uncovering it was the first move towards prayer. In this, it revealed its contents like other decorative objects (Randolph 2014, p. 135).

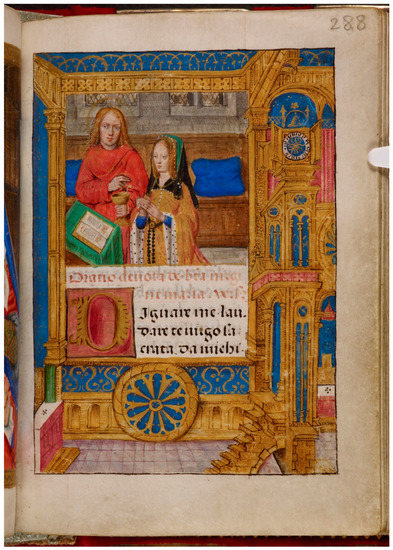

Whilst Juana did not write prayers in her hours, there is evidence she commissioned a miniature after a painting by Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400–1464), added soon after the hours were compiled (Nash 1995, p. 437). The Virgin breastfeeding (Virgo lactans) (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 287v, Figure 2) faces Juana kneeling at her prie-dieu (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 288r, Figure 3). Nash considers the fictive frame in the miniature of the Virgin and Child to be a clue that the miniature was copied from a Burgundian altarpiece. Paintings of the Virgin and Child by Van der Weyden and his followers abound across France and Belgium, and the panel of ‘La Vierge à l’enfant’ [Virgin and Child] in the National Gallery of Belgium, although commissioned for other donors (Martin Reynhout and Barbara van Rockaringen) is thought very similar to Juana’s miniature.24 Other panels by Van der Weyden, ‘La Vierge et l’enfant’ [Virgin and Child] also echo it.25 Nash speculates it was copied from a panel owned by Juana comparable to the Reynout one: ‘we may have here another very specific copy in manuscript form of a favourite devotional image, possibly owned by the patron’ (Nash 1995, p. 437). She argues that the panel with the Reynhout coat-of-arms is ‘unlikely to have been owned by Juana’ (Nash 1995, p. 437). Nash’s view is wide of the mark. According to the inventory of Juana’s possessions, she had five altarpieces of the Virgin and Child, including one identified as Greek and another embroidered one. One of the altarpieces specifically mentions the coat-of-arms of a Flemish nobleman on the upper part of the panel:26

From the description of Juana’s panel, it is almost certain that it was the one currently in the National Gallery in Brussels. Juana kept it safely protected in a chest. This emphasizes its importance to her and why she had it copied into her hours.27a panel in a chest of Our Lady with her child in her arms breastfeeding with one hand on her breast and the other behind the body of the child. And her hair was loose and her eyes on the child. It is painted by brush. She is wearing a white headdress with blue cloak and the dress is ruddy and, in the upper part, there is a coat-of-arms of a Flemish nobleman. The frame is gilded and the panel outside painted in black.(Ferrandis 1943, p. 230, fol. 64r et seq.)

Figure 2.

London, British Library, Add. MS 18852, fol. 287v. Virgin and Child, Virgo lactans.

Figure 3.

London, British Library, Add. MS 18852, fol. 288r, Juana at prayer with St John the Evangelist.

The artist positioned Juana kneeling on the righthand page in the presence of the Virgin Mary (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 287v–288r, Figure 2 and Figure 3), a frequent response to acquiring a new book (Sponsler 1997, p. 104). The miniature Juana directs her gaze at the Virgin, bride and mother, no doubt signifying that, as a young bride, soon to be mother of the Archduke, she sought to place herself under the Virgin’s aegis as mother of Christ, King of Heaven. This double page is like the diptychs of devotee and saint frequently found in Burgundian altarpieces.28 Such portraits set the owner in a sacred posture surrounded by holy figures and can be read as a commodification of the devotional body (Sponsler 1997, p. 107). While we cannot be sure how Juana viewed herself in her book of hours, there can be no doubt that Juana was especially devoted to the miniature of the Virgin and Child. In Juana’s book, the diptych is well thumbed, as indicated by the dirt (Rudy 2010, n.p.) on the edges, suggesting the book was held open often there.29 Juana dedicated time to contemplating pictures of the Virgin, using her hours but also her altarpieces to inspire her prayer (Reinburg 2012, pp. 109, 112–127).

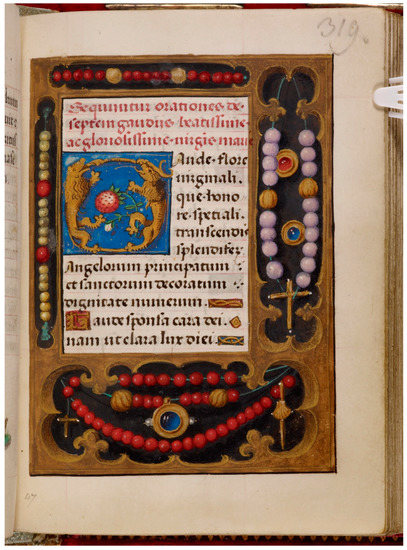

Juana’s devotion to the Virgin could also have been served by turning to the seven joys of the Virgin in her book of hours (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 319r).30 The joys are not celebrating the events of the Virgin’s life but belong to a hymn on the Seven Celestial Joys by Thomas of Canterbury: ‘Rejoice, virgin flower’, ‘Rejoice, God’s dear bride’, ‘Rejoice, splendid vase of virtues’.31 A rosary book in the Chester Beattie Library, Dublin, belonged to Juana and her hours contains a rosary devotion on the Virgin’s seven joys (Miralpeix Mestres 2007, p. 370).32 On the opening folio of the joys is another trompe l’oeil depiction of four jeweled rosaries embedded in carved wooden casings (London, British Library, Add. MS 18852, fol. 319r, Figure 4). The rosary miniature is replicated in other Flemish books (As-Vijvers 2007, p. 45, fig. 16b). In fact, Juana possessed numerous rosaries at the time of her death, showing that she not only contemplated the rosary miniature, but also frequently held and prayed the rosary.33 Ten rosaries are recorded in the inventory of her possessions. There are rosaries with reliquaries attached and one rosary with the mysteries of the Passion attached (Ferrandis 1943, pp. 207–20, fols 64r–82). Juana possessed numerous sets of beads, not called rosaries, similar to the beads depicted in her hours (fol. 40r) (Ferrandis 1943, p. 208). The rosaries she possessed are sometimes of 55 beads and sometimes of 52. Some have gold beads. There is one of coral.

Figure 4.

London, British Library, Add. MS 18852, fol. 319r. Rosaries.

Since her book was rebound to include the new miniature, Juana extended her devotion to the Virgin by commissioning prayers. The seven joys are followed by a series of well-known Marian prayers including the ‘Salve regina’ (fol. 321v). The final prayer, ‘Ave sanctissima Maria’ (fol. 322v), ends with the only capitalized ‘Amen’ in the book of hours. In this ‘Amen’, the letter formation is different to the others in the same section of the book of hours, particularly different is the capital A of ‘Amen’. This Ave prayer may have been one of Juana’s favorite prayers added to the book of hours for her. Although the marginalia are constant with the remainder of the book, several decorated folios are otherwise blank (fols 41v, 349v). Prayers could be easily added to these blank folios.34

At the same time, she took the opportunity to have other prayers added for her. Juana had a section of prayers dedicated to the Virgin copied, beginning with the antiphon, ‘Let me praise you, holy Virgin’.35 The first of the prayers was the ‘At the feet of your Holiness, most sweet Virgin Mary’ (BL MS Add. 18852, fol. 288v), a prayer popular from the late fifteenth century onwards. Particularly valued were the words of the ‘Memorare’, ‘Remember, most merciful Virgin Mary, never was it heard that anyone who turned to you was left unaided’.36 It is significant that the prayers and miniature commissioned at Juana’s request all illustrate her devotion to the Virgin and taking the Virgin as Queen as a model, because she was a future ruler.37 She also, no doubt, modelled herself on her mother and her well-known devotion to the Virgin (Graña Cid 2018, pp. 142–43). Yet another important feature of Juana’s prayer book is the way one part of it was transmitted for her daughter through the moral or conduct section of her book I explore next.

3. Juana’s Hours and Its Influence on Behavior

Conduct guides for women abounded in the Middle Ages and were another indicator of how women’s spirituality might be channeled, since such idealized models for behavior could lead medieval women to ‘interior prayer’ (Grisé 2002; Innes-Parker 2016, p. 241). Yet conduct books were also a way of controlling and disciplining women (Sponsler 1997, p. 60). Juana acquired five well-known ones over the course of her life (Ferrandis 1943, pp. 225–33, fol. 64r et seq., 225, 226, 230).38 Using a prayer book was a related way of guiding women’s behavior, as Juana’s hours, with its numerical teachings and moral instructions, shows. Miniatures in the ‘behavioral’ section of Juana’s prayer book are ways of confronting the female user with consciousness of imminent death and decay, both likely to provoke greater attention to the spiritual. Enumeration of sins allowed them to be countered by prayer and prayers with indulgences were another means of reducing time in purgatory, acting as a counterweight to sin.

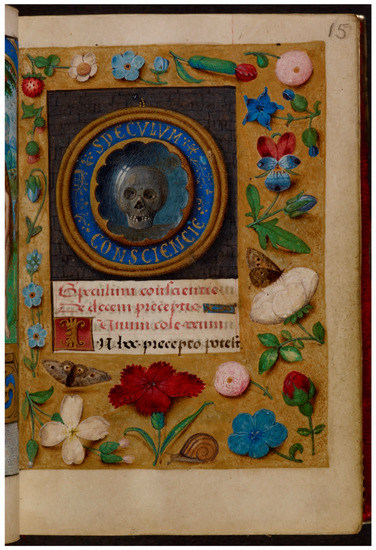

In Juana’s book, the instructional section opens with a mirror, marked in gold lettering with the words ‘speculum conscientie’, hanging as though in a gallery. As Juana looks into it, her own demise unfolds before her. The mirror of conscience seeks to bring Juana face-to-face with her mortality to enhance her piety (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 15r, Figure 5).39 Death and examination of conscience are entwined, and death will eventually be a young woman’s lot. The illuminator successfully replicates the realism of the concave curve of the mirror through subtle reflections, highlights, and shading (Marrow 1983, p. 157). Its trompe l’oeil perspective makes the mirror stand out to the reader, yet it alludes subtly to the many medieval compendia of knowledge such as Vincent de Beauvais’s Speculum Maius, a treatise on right conduct, or Guy Marchant’s 1486 Danse macabre (Marchant 1486) with its title Mirror of salvation for all men (Marrow 1983, pp. 157–58). The mirror, reflecting a grinning skull back at those who open this page, faces a full-page miniature of Adam, Eve, and the serpent, set in an architectonic frame, together with, to the left, Adam and Eve expelled from the garden (BL Add. MS 18552, fol. 14v). The overall impact of seeing the mirror facing the Fall reflects at Juana her own mortality, human sin, the passing state of human life, and the path towards death.40 Juana’s awareness of sinfulness, decay of beauty, and death is attested by her ownership of a gold agnus Dei with a cameo of a naked woman holding a mirror on one side and a serpent on the other (Ferrandis 1943, p. 220).41 The pairing of images of sin and death, as in the double spread in Juana’s book or on her agnus Dei, is not uncommon (Smith 2003, p. 152). Just like Juana’s diptych, Margaret Beaufort’s hours offer an experiential double vision of misguided pursuit of sin, typical of late-medieval ingenuity in designing books of hours (Smith 2003, p. 152). The Beaufort hours miniatures of the Three Living and the Three Dead is comparable to the miniature of the skull in Juana’s hours. Both offer a message to keep from pursuit of the world’s vanities (Marrow 1983, p. 159).42 Juana, faced with the skull and mirror, is to contemplate her end but, in its ‘de-anecdotalised’ state, the mirror invites her to contemplate freely (Marrow 1983, p. 161).

Figure 5.

London, British Library, Add. MS 18852, fol. 15r. Speculum conscientie.

Contemplating the mirror and skull may have been how Juana most often used these pages of her book of hours. The speculum conscientie shows a fair amount of wear along the lower sides of the folios, suggesting the book was held open by the middle to lower sections (Rudy 2010, n.p.).43 Heavy soiling on the page suggests that Juana used it regularly, although it is of course impossible, at five centuries remove, to separate Juana’s response to the book from the simple curiosity of later owners.44 If this wear corresponds to Juana’s use of the book, it suggests pictorial representations of mortality and of original sin were more important to her than the teachings that follow. The mirrored skull brings mortality into her presence in a similar manner to the figures and events of the Passion in Duchess Margaret of Cleves’s hours (Marrow 1996, p. 107). Juana’s tendency to meditate on the skull miniature is further borne out by her owning a gold enameled skull, which no doubt served a meditative purpose (Ferrandis 1943, p. 209).45

The behavioral section of Juana’s hours is replicated in a Burgundian Psalterium for personal devotion (GKS MS 1605, fol. 284r).46 The Psalterium, thought to be owned by Juana’s daughter, Isabel (1501–1526), may provide a tantalizing insight into Juana’s prayers. It signals that the precepts were close to Juana’s heart, since they were copied in the same order for her daughter’s Psalter.47 It may even mean that Juana, Isabel, and others at court voiced them together, each using their own copy. Isabel’s Psalterium begins its speculum conscientie with ‘there follows the mirror of conscience’ (CMB MS GKS 1605, fol. 19v).48 There is, however, no mirror depicted, unlike in Juana’s book of hours. Isabel’s Psalterium depicts a skull only on the margins of the Vigil of the Dead (CMB MS GKS 1605, fol. 284r). Although the words are replicated, the reader is less drawn to death’s omnipresence than in Juana’s book without the visuality of the mirror. It should be noted that skulls and bones are also used to decorate the office of the Dead in many books of hours, such as in a Maastricht hours and prayer book (KB MS 74 G 36, fol. 112r), in a Bourges hours (KB MS 74 G38, fol. 106r), or in Juana’s daughter’s psalter (GKS MS 1605, fol. 284r). They offer a less complex view of mortality than the speculum conscientie miniature but also reinforce how death is ever-present for late-medieval readers.49

Juana’s speculum offers a series of instructions about right behavior. Such a ‘catechesis’ has been considered ‘unusual’ in a book of hours, although it may have been ‘judged appropriate for a young wife’ (Kren and McKendrick 2003, p. 385). There are a number of possible models for Christian instruction: Catechesis, or instructions about the faith; doctrine, or instruction about the Church’s teaching; and moral guidance, such as the 10 commandments or the theological or cardinal virtues. Juana’s book contains a combination of these, including the 10 commandments, the seven deadly sins, the theological and cardinal virtues, the five senses, the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, and the seven sacraments.50 It is certainly the case that this section of Juana’s hours provides guidance to her on aspects of Christian teaching and offers insight into how Philip and his advisers saw her role.51

One reason for this section of the hours was to prepare Juana to teach her children, giving them the spiritual benefits of religious instruction.52 Using words from the Bible or the Church Fathers, they provide Juana with orthodox teachings to impart (Bell 1982, pp. 755–57), particularly to girls. Hours or primers were used by women for teaching their children (Rudy 2006, p. 66). Joni M. Hand (2013, p. 182) believes the script in Juana’s hours was too difficult for a child to read alone but perfect for guided reading. There are many examples of numbered prayers, such as the seven Penitential Psalms or the five senses, being used to teach literacy (Pearson 2005a, pp. 41–42; Hand 2013, pp. 76, 185).53

The teachings in Juana’s hours begin with the 10 commandments: ‘de decem preceptis’ [on the ten precepts], encouraging her to refrain from sinning (BL Add. MS 18552, fol. 15r). After each commandment, the book of hours lists examples of how it might be broken. The first commandment is to love God: ‘unum cole Deum’ (BL Add. MS 18552, fol. 15r). Instruction about not contravening this precept means avoiding bad faith, idolatry, and other practices bordering on necromancy, such as summoning demons or divination: ‘from this precept a person can sin by following the senses in bad faith, committing idolatry, invoking demons, divining, or observing superstitious feasts or celebrations’.54 Following the commandments, the seven deadly sins are listed, beginning with pride (BL Add. MS 18552, fol. 19r).

Each of the sins in Juana’s hours is followed by examples. Under pride, Juana’s book set out what constitutes pride: ‘under this precept can be found anyone who desires dignities, honors, or preferential treatment, sins’ (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 19r).55 Juana was to note the different constituents of pride in order to avoid them. A Castilian Libro devocionario [book of devotions] (BN MS 6359, fol. 211r) begins prayers against the seven deadly sins with the following rubric: ‘there follow prayers against the seven deadly sin and the first is against pride’ and, although Juana’s book has no rubric about praying against the deadly sins, it may be intended to instigate such prayer.56 Juana is encouraged to know the activities that constitute the seven deadly sins in order to pray against them. The prayers they evoke may be voiced in Latin, in Castilian, or be an interior wordless plea for heavenly aid. What is more, the seven deadly sins could move the prayer to examination of conscience. Enumerating the types and subtypes of sin drew attention to the sins (as the speculum conscientie suggests). The hours then served the purpose of penitent self-examination (Smith 2003, p. 249).

Although most books of hours did not incorporate instructional sections, some include doctrines or Christian requirements, with certain similarities to Juana’s. Some included ways of controlling mind and body (Madrid, BN MS 6539, fol. 5r; Escorial MS a-III-15, fol. 1v).57 One book of hours instructed when fasting is required: ‘on the four times of fasting’ (Madrid BN MS Vitr. 25.4, fol. 13r).58 Another one instructs on making a good confession: ‘condiciones bonae confessiones’, advising on the right mindset: ‘let it be a simple, humble, pure confession’ (Madrid BN MS Res. 187, fol. 16v).59 A third includes a short outline in French of the Catholic faith (Liège Université MS Wittert 26, fols 224–28). Juana’s also emphasizes the salvific effect of the Church’s teaching.

Occasionally, hours provide behavioral instruction in the vernacular. One Spanish devotional book outlines doctrine necessary for salvation: ‘this is the teaching each faithful Christian should know to save his soul’ (Madrid, BN MS 6539, fol. 4r).60 Queen Isabel, Juana’s mother, had a prayer book with a series of instructions in Catalan for prayers to say during the stages of Mass: ‘as you start to enter the church, you will say the following: I will come into your house, I will show adoration to your temple in awe of you’ (Escorial, MS Vitr. 8, fol. 22r).61 There were hours with prayers in French to be said at principal points during the Mass (The Hague, KB MS 76 F 16, fols 129r–136r) (Rudy 2016, pp. 188–98).62 There was a prayer to say when leaving the house, another for entering the Church, one to say in front of the Cross, and two prayers to say after receiving the sacrament. Prayers might accompany activities or points of the day, such as getting up or confession (Liège Université MS Wittert 31, fols 140r–142r). The hours owned by Alphonso of Aragon (1396–1458), Juana’s great-uncle through her father’s line, includes prayers for rising (BL Add. MS 28962, fol. 15r), as well as for battle (fol. 77r), and for a victory (fol. 78v).

Rubrics in many hours involved reciting prayers accorded indulgences: ‘he who says the canticle Magnificat each day will attain thirty days of relief from Purgatory, granted by the blessed Father’ (Madrid BN MS 6539, fol. 9r).63 Such prayers are beneficial, as they hasten access to heaven for devotees, a feature of medieval life well recognized from endowing chantries. Reducing time in Purgatory for oneself and family members was essential. Juana’s book of hours has an unspecified indulgence for repeating a prayer to the Virgin: ‘O intemerata’ (BL MS 18852, fol. 132r), attributed to Edmund of Canterbury (1125?–1240): ‘and all those saying this prayer devoutly are granted great indulgences’.64 Rubrics to some of Juana’s prayers suggest these are ‘very devout’: ‘very devout prayer to the name of Jesus’ (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 323r).65

4. Juana’s Hours: The Office of the Guardian Angel, Defeat of the Devil, Cleansing from Sin, and Baptismal Promises

Spiritual attack by the devil could be overcome by St Michael and the angels and medieval men and women appreciated angelic intervention at important points in their lives. Combatting the devil was often expressed through invocation of the salvific power of the Guardian Angel, a frequent subject of altarpieces commissioned by the faithful and suffrages pleading for his help. Christ’s Passion was another familiar way for medieval people to recognize the defeat of sin, whilst devotion to the events and images of the Passion reinforced their continuous spiritual battle against their own weakness. In Juana’s prayer book, a combination of prayers to the Guardian Angel, prayers on Christ’s healing ministry, and prayers to the Holy Face of Christ offered spiritual protection to those repeating them.

Juana’s book (BL Add. MS 18852) stands out from many others, because it has an office dedicated to the Guardian Angel. The office of the Guardian Angel was considered unusual for northern Europe, where Juana lived as archduchess and where her book was produced, although Elizabeth Woodville is known to have owned such hours (Sutton and Visser-Fuchs 1996; Hand 2013, p. 76). How owners handled their manuscripts shows some prayed often to the Guardian Angel (The Hague, KB MS. 74 G 35) and the wear on Juana’s manuscript tells the same story. Unlike the speculum teachings discussed earlier, there is heavy usage on the facing folios of St Michael and Juana kneeling at prayer (BL Add. MS 18852, fols 25v, 26r, Figure 1). St Michael is accorded a full-page miniature facing Juana, accompanied in prayer by her namesake, John the Baptist, and her Guardian Angel (BL MS 18552, fol. 25v). In the miniature, Juana’s gaze falls on St Michael defeating the devil. A book of hours is open on her prie-dieu, but her eyes lift away from it into the spiritual realm and towards the patron of her adopted city. Many hours, particularly those produced in the duchy, begin with suffrage to St Michael. She too commits to angelic defeat of the devil, as she is guided to follow the teaching contained in her speculum conscientie.

The cult of the Guardian Angel was popular in Spain, whilst the ‘Good Angel’ was known in both the Low Countries and Spain (Sutton and Visser-Fuchs 1996, p. 232), particularly in Catalonia because of the dissemination of Eiximenis’s Llibre dels àngels (Gascón Uris 1993; Martí 2003). There are some Low Countries hours with well-thumbed suffrages to the Good Angel (Rudy 2010, n.p.):

This suffrage to the Angel calls for protection at the time of death. In the peninsula, an Aragonese hours, previously owned by the Count of Benahavis, begins with the office of St Michael (Madrid BN MS Res. 197, fol. 1r), representing all other angels. This office includes an antiphon invoking St Michael as ‘angelus custos’ [Guardian Angel] (fol. 20v). Like Juana’s hours, this one was written for female owners, for it belonged to the Bernardine nuns at the Toledo San Clemente convent. The nuns’ office of the Guardian Angel emphasizes protection from evil during earthly life (Madrid BN MS Res. 197, fol. 64v) rather than at the time of death. One prayer asks the Guardian Angel to ensure the nun receives instruction in the faith: ‘the third prayer is that with your presence you might instruct me deeply in the faith’ (fol. 63v).67 The nuns’ book has the office of St Michael, followed by that of the Guardian Angel, meaning it begins with a double invocation of angelic protection (fol. 61v).To the Good AngelI ask God’s holy angel sent down to me from our Lord Jesus Christ that you take my soul and my body in your hands.(The Hague, KB MS 133 M 124, fol. 60v).66

The Guardian Angel hours are clearly intended to protect Juana from temptation, sin, and the world. When considering why the office of the Guardian Angel is included in Juana’s hours, it should be remembered protective power was applicable to a young bride about to engage in pregnancies and births, investing the hours with almost magical or talismanic power (Smith 2003, p. 252). Such an act was common, for a Life of St Margaret could be clasped to the belly of a pregnant women (Reinburg 2012, p. 187). Juana’s office includes the prayer:

Glorious Guardian Angel who was sent at my birth from the womb to watch over me from the heavenly realm, I pray you humbly and devoutly that, as I am entrusted to you, enlighten, arm, and defend me.(BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 27r).68

In the prayer book of Philip the Good of Burgundy (Hague KB 76 F 2) compiled some 40 years earlier, a prayer to St Michael begins in a very similar way to Juana’s: ‘Angel, who are my guardian, as I have been committed to you with your heavenly mercy, serve, defend and rule over me’ (fol. 3r).69 A second prayer to St Michael invokes the tripartite protection he affords:

Like Philip the Good before her, Juana is to place herself under angelic protection, as she begins her reign. The personage of St Michael conquering the devil took part in Juana’s Burgundian pageant in 1496 (Tammen 2011, p. 216) and his presence would serve as a reminder of her arrival there and, thus, reinforce recall of her wedding vows.71 Juana seems to have prayed the morning office most frequently (fols 26v, 27r). Her devotion to the Guardian Angel casts new light on belief in Juana’s demonic possession alleged at the end of her life (Fleming 2018, pp. 305–25). Moreover, Juana’s devotion to the Guardian Angel was passed to her daughter, Catalina de Austria (1507–1578), who lived longest with her in Tordesillas. Catalina, in her will, asks for protection at the hour of her death from the Guardian Angel and all angels, as well as from other saints including John the Baptist, St Anthony, and St Catherine (Simancas, Archivo General, PTR. Leg. 29, Doc. 27, fol. 488v).I pray you Father, Lord, angel spirit, minister of the heavenly realm who Almighty God sent for my custody that you may ever protect, visit, and defend me, waking and sleeping, from any attack or incursion of the devil.(KB 76 F 2, fol. 2v).70

Juana’s book celebrates Christ’s life and ministry from his baptism by John the Baptist with an important emphasis on John baptizing Christ, setting one of Juana’s two patrons at the initiation of Christ’s ministry. The miniature also serves as a wordless reminder of Juana’s own baptismal promise and faith. John the Baptist’s feast was a red-letter day across Castile and Aragon, marked by a short commemoration in Queen Isabel’s breviary (Escorial MS Vitr. 8, fols unnumbered).72 John the Baptist, the last of the prophets, marks the transition between the Old Testament and New and, also, symbolizes transition to a new public life in Juana’s own circumstances.

Christ’s ministry in Juana’s hours makes reading Scripture possible for a laywoman. What is interesting about the series of prayers on Christ’s life is how it centers on biblical women. Christ heals numerous masculine figures, although these are listed only in categories: ‘those possessed by the devil you freed, you brought the dead back to life, you healed lepers and cured the lame and dumb’ (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 37v).73 The ministry prayer in Juana’s hours is explicit in its treatment of the women Christ met and healed:

First, the female figures are differentiated in a way that the male figures are not. For example, the ‘dead raised’ include both Lazarus (John 11.43) and the son of the widow of Nain (Luke 7.11–16). Explicitly identified are the woman healed of a hemorrhage (Matthew 9.20; Luke 8.43), the woman taken in adultery (Luke 7.37–50; John 8.3), Mary Magdalene made clean, the unnamed woman at the house of Simon the Pharisee whose sins were forgiven [Luke 7.36–49]), and the woman crippled for 18 years (Luke 13.11–16). Each of these women in relationship with Christ demonstrates a need for healing or cleansing and symbolize how Juana, like all women, needed cleansing from her sin. The prayers end with words of thanks to Christ: ‘Lord, I thank you for this and other signs’.75You freed the woman taken in adultery; you cleansed Mary Magdalene of her sins; you healed the woman with the flow of blood; you made the woman asking for her daughter happy; you raised the woman crippled for eighteen years; weary you sat at the fountain, enabling the women speaking to you to recognize you; you caused the woman’s heart to become inebriated so she exclaimed: ‘Blessed is the womb that bore you and the breasts which gave you suck’.(BL Add. MS 18852, fols 37v–38r).74

Prayers to St Veronica, found in Juana’s other book of hours (BL Add. MS 35313), have a similar purpose. Handling of a devotional object, such as the vernicle, is part of ‘performing gender’ and the same applies to how it is depicted as an object of devotion (Clark 2007a, p. 166). In BL Add. MS 35313, Veronica holds her veil, the record of an encounter between a woman and Christ (Swan 2002).76 Hans Belting (2006, p. 236) associates the image of Christ’s face on the veil with the Real Presence. A medal icon of Veronica holding the cloth with its imprint accompanies the office of the Passion of Christ at terce in Juana’s book (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 54v). Reinburg (2012, p. 117) notes that pilgrim badges, engravings, and sculptures often illustrate the Passion. Juana’s hours again memorialize the vernicle in the shape of a medallion (fols 395r–v) on two facing pages. Christ’s face appears on pilgrim badges on the border of St Luke’s Gospel (fol. 184r), with one depicting Christ’s Passion and another Christ’s face superimposed on a cross. Another medal of Christ’s face is on the lower border in the Psalter (fol. 344r). Juana owned a vernicle altarpiece and, several vernicles in silks.77 The vernicle medals commemorate Juana’s devotion, consistent with the many vernicles she owned. Juana’s devotion to the Passion is affirmed in the ‘London Rothschild Hours’ (BL Add. MS 35313), supposedly Juana’s. In the Rothschild Hours, the first office is ‘on the Vernicle or Holy Likeness’, and there is a miniature of Christ’s face imprinted on Veronica’s veil (fols 17v–32v), followed by the hours of the Holy Cross (BL Add. MS 35313, fols 32v–39v).78 The same prayer separates two offices of the Passion in Juana’s hours (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 66r) under the rubric ‘The Salutation of Blessed Veronica’.79 Veneration of St Veronica was well established at the Burgundian court, stemming from the belief she could ward off unexpected death, preventing access to the sacraments (Hand 2013, p. 125). This belief may also explain why this subject is found in many books of hours, including Juana’s.

Protection against sin, death, and the devil predominates in the office of the Guardian Angel, the prayers on Christ’s ministry, and the miniatures and offices of the Passion. The prayer in Juana’s office of the Guardian Angel requesting his protective power aligns with the Burgundian tradition of devotion to St Veronica, a noted protectress from untimely death. Christ’s relationship with each of the biblical women and his cleansing of each of them was understood as a personal encounter with salvation. This encounter aligned with Veronica’s retention of his physical presence in the form of a cloth that would through the centuries enable other women to meet him and be saved.

5. Selected Saints and Juana’s Prayers

Devotion to particular saints, whether ones of national or family importance, is another way of discerning how men or women might seek to identify with the spiritual realm. The saints privileged in Juana’s book and how they correspond to national patrons, both from her homeland and new land, is a starting point. The relationship of the saints to Juana’s own life seems then to have led her to identify with certain ones. Study of the saints provides another avenue for gaining insight into her spiritual preferences.

The closing section of Juana’s book provides a short sanctoral or offices of selected saints. These were no doubt intended to be of major interest to Juana, both as a matter of taste and national significance. Each of the eight saints chosen is a major saint in Burgundy or Spain: St James, patron of Galicia and Leon; St George, patron of Aragon and Guild patron in Ghent, St Michael for Brussels, and St John the Baptist, Juana’s patron saint (Crombie 2015). Juana’s book has short suffrages for three female saints, listed in the order they appear in the liturgical calendar: St Mary Magdalene (22 July), St Catherine (25 November), and St Barbara (4 December).80 Given that the proportion of women saints included in collections of lives of saints was relatively small, the proportion of female saints in Juana’s book of hours is high (37%),81 which reflects the fact that privileging female saints in hours for women patrons was frequent (Lerer 2012, p. 414).82 For example, the hours of Charles V, Juana’s son, contains prayers for 23 male saints, whilst there are nine female ones (28%). Charles V’s hours have offices for St Mary Magdalene, St Catherine, and St Barbara, along with saints appropriate to Charles’s role as Holy Roman Emperor, including St Susanna, a Roman saint, and St Helena, mother of the Roman Emperor, Constantine (Madrid, BN MS Vitr. 24.3, fols 304r–313r). Charles V’s book places St Helena (fol. 304r) in pride of place, before Mary Magdalene (19 July, fol. 304v).

Juana seems to have favored certain offices and suffrages, given the soiling apparent on certain pages of written prayers. The suffrage texts displaying the most signs of soiling are those of St James and St Barbara. Juana’s devotion to St James is also commemorated by a medal in the margins of her book (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 50v). St James bearing his pilgrim staff accompanies the morning office of Christ’s Passion. St James’s scallop is represented on the border at prime and sext in the office of the Virgin, serving as a reminder to Juana of her Castilian identity (BL MS Add. 18852, fols 234v, 248v). One of the rosaries in the miniature (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 319r) has the shell and staff of St James hanging from it. The suffrage to St James is decorated with scallops and crossed pilgrim staffs (fol. 412r). Among her possessions, Juana had a figure of St James in jet.83

As in Juana’s book, John the Baptist was often the first of the suffrages in books of hours.84 In the first miniature in Juana’s book, John the Baptist stands as her patron. However, it is known that Isabel la Católica sought the protection of John the Evangelist, commissioning a treatise on him (Talavera 2014) and adopting John the Evangelist’s eagle wings for her coat-of-arms. In the second self-portrait (fol. 288r), John the Evangelist accompanies her, facing the miniature of the Virgin Mary. Mary facing John the Evangelist would have been familiar based on images of the crucifixion that often represented him at the foot of the cross with Mary (into whose care she was given). When the new miniature was commissioned, Juana ensured her mother’s preferred patron accompanied her in the presence of the Virgin.

The three female saints are all celebrated in both Spain and the Netherlands.85 Mary Magdalene had prime historic importance for the house of Burgundy (Pearson 2005b, p. 58). Her relics had assisted in legitimizing the dynasty. Authenticated by the Pope in the 11th century and held in the abbey church of Vézelay (Franche-Comté), they were venerated in the heartland of the duchy. Identification of the house of Burgundy with Mary Magdalene remained strong in the 15th century (Pearson 2005b, p. 52).86 Devotion to Mary Magdalene was equally strong at the Castilian court. Juan de Flandes (c. 1460–1519) is thought to have taken the Princess Catherine (of Aragon), Juana’s younger sister, as his model for Mary Magdalene, revealing that the saint’s virtues were more important than association with prostitution, making her fitting for a young princess to adopt as a model.87 Other paintings of Catherine dressed as Mary Magdalene include one by Michel Sittow.88 These many paintings of Juana’s younger sister meant Mary Magdalene occupied a place close to Juana’s heart. The suffrage to Mary Magdalene shows some sign of wear, particularly at the full-page miniature, although there is less on the words of the suffrage.

Next among the suffrages, Juana’s hours commemorate St Catherine of Alexandria.89 St Catherine was a favorite saint in the late medieval period,90 patron saint of maidens, and of philosophers, students, and theologians (Germing 1932, p. 56). As noted earlier, suffrage to St Catherine has its place in all but one of the books of hours produced for Spain, revealing her cult was widespread there (González Hernando 2012), whilst more lives of St Catherine have been written than of any other saint. Evidence of Catherine’s cult is also visible in hours commissioned for Spain. One simply written hours, with rubrics and instructions in Castilian, has St Catherine hours, underlining her importance in Castile.91 She is the only saint with a dedicated office in that simple Castilian book, for the other offices are dedicated to the Virgin, the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, and Corpus Christi.

Juana’s devotion to St Catherine is also marked by the medal of St Catherine in the margins of her book (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 61v) and Juana’s continued devotion is manifest in her possessing an alabaster statue of Catherine (Ferrandis 1943, p. 231).92 The miniature (BL Add. MS 18852, fol. 417v) accompanying the suffrage to Catherine is more heavily soiled than the text of the suffrage (fols 418v–419v), suggesting Juana may have turned more readily to looking at the miniature.

St Barbara is the third of the female saints in Juana’s sanctoral. The cult of St Barbara spread in northern Europe (Lockwood 1948, p. 29; Cassidy-Welch 2009, p. 378). Late-medieval versions of Barbara’s life associate her with devotion to the Eucharist. In Spain, the cult of St Barbara was equally strong with shrines and hermitages dedicated to her across the kingdoms. St Barbara’s presence in Aragonese altarpieces is typified in Luis Borrassà’s predela of saints, featuring panels of John the Baptist and St Barbara (Grace 1934, pp. 11–14).93 In central Castile, St Barbara’s feast day was often a red-letter day (León Archivo de la Catedral, MS 36, fol. 7v). Shrines to St Barbara are frequent in the Kingdom of Valencia and fortified towns like Lliria, Rocafort, and Chulilla take her as patron. Another famous fortified town, Alicante, had its castle dedicated to her in 1248. As noted earlier, Barbara was one of the female saints most often included among suffrages to saints and Juana’s devotion to Barbara is attested by having an alabaster statue of her (Ferrandis 1943, p. 231).

The female saints included in Juana’s hours are ones she was directed towards by her husband but there is also evidence that she responded to some more than others. There is evidence of handling on the middle to lower edges of the book for the full-page miniature of Barbara (BL Add. MS 18852, fols 420v–421r). The text of the suffrage also shows sign of handling in the middle to lower sections of the right-hand margin (fol. 422r), suggesting that Juana (or later users of the book of hours) favored it more than she did other female saints. Given that St Barbara’s story involves her being locked away in a tower by her father, its synergies for a queen locked away and ill-treated by husband, father, and son are striking.

In the Rothschild hours, some of the same female saints are venerated, together with additional ones: St Anne, mother of the Virgin (BL Add. MS 35313, fols 230v–231r), St Margaret of Antioch (fols 234v–45v), and St Elizabeth of Hungary (fols 235v–236r). St Anne was venerated and invoked by childless noblewomen or during pregnancy in the Kingdom of Valencia during the 15th century and prayers to her were added to prayer books during the late 15th and early 16th centuries (Twomey 2017; Rudy 2016, p. 332). St Margaret of Antioch was another saint with powers over pregnancy and patron saint of childbirth, because of her victory over the dragon and how she emerges from its belly (Dresvina 2017, p. 188). Elizabeth of Hungary, namesake of Juana’s mother, was queen and married saint. This trio of saints (BL Add. MS 35313), would have proved fitting for Juana to venerate during her later married life, giving value to the many pregnancies she underwent. While the short suffrages in Juana’s book (BL Add. MS 18852) would have been appropriate for the early stage of Juana’s life as a new bride, the venerated saints in the Rothschild hours would have been appropriate to a young married woman engaged in providing heirs for her husband’s dynasty.

6. Conclusions

The prayers in this book of hours reveal hidden details about Juana’s life and prayer. The book, gifted to mark Juana of Castile’s marriage or shortly after, combines narratives designed to instruct her in correct behavior and in relationship with God with specially chosen precepts, offices, and suffrages.

First, the emphasis of the speculum conscientie on duty, obedience to God, honor of parents, rejection of sin, seeks to situate Juana’s married life in this frame. The purpose of the doctrinal guidance guides her in positioning the words she is to vocalize within a context of remembrance of her own mortality as well as of obedience to God, the Church, her parents, and her husband. The precepts and memento mori focus the bride’s attention from the opening words of her hours on her immortal soul. She witnesses her own mortality, curbs her senses, and is not to resist the will of her parents who arranged the marriage, and of her husband to whom absolute obedience is of paramount concern.

Prayer was public and voiced and the precepts included in the speculum conscientie in Juana’s hours are intended for speaking. Words are seen, heard, touched, and spoken. Indeed, in the performance of prayer, whether kneeling, sitting, holding the book, opening the book, letting the eye engage with self in miniature, private altarpiece, or a set of words, prayer is seen, known, and recognized by visitors to the household, such as Prior Tomás. Walking with the book would signal prayerfulness. Once the duchess’s chamber or chapel was reached, all that remained was to uncover the book with visual and sensual proximity acting as a trigger for prayer. Prayer’s public function, for prayer was a very visible—and audible—act, was capable of positioning a new duchess in her husband’s court. Carrying the hours, unopened in its rich chemise, signaled Juana’s wealth and status but also her spiritual intention.

Even if the instructional section was not spoken publicly for devotion, as teaching material it would be read aloud. The familiar words of the 10 commandments, seven deadly sins, and other number-related precepts are believed appropriate for the young duchess. Two parts of the speculum are included in the Psalterium (CMB MS GKS 1605), indicating she found them sufficiently valuable to replicate for her daughter or that traditionally in Burgundy it was so.

Second, the prominence of biblical women and their relationship with Christ offers a model for Juana’s own relationship with Christ. The prime position of women saints in books of hours has been noted but not the presence of women in Christ’s ministry. Both have a parallel purpose: Enhancing the engagement of women when prayerfully working through the acts of Christ’s ministry. Christ’s relationship with sinful women marks the view of Philip or of his adviser about women’s nature.

This section of the book also emphasizes the initiatory role of St John the Baptist, one of Juana’s patron saints. John the Baptist is a transitional figure, the last of the prophets, and the first to recognize Christ’s ministry. As Juana’s namesake, he marks the start of transition for her to a new life, far from home, as a married woman. His positioning at her side, along with her Guardian Angel, in the miniature accompanying the office places her prayer in the context of new beginning, new ducal ministry, new nuptial promises, but also of sacrifice.

The tiny handheld book of hours with its office of the Guardian Angel might have acted as a talisman to assist in future pregnancy and childbirth. The protective power of the Guardian Angel indicates to a young wife that clasping it would convey support for the dangers of pregnancy and childbirth, the lot of female consorts. Although the book has no specific handwritten prayer about childbirth, a husband gifting it to his wife might believe holding it would protect her. In later life, Juana may have continued using the hours as a talisman to guard against other danger she perceived, much as she used her agnus Dei.

The suffrages enable Juana’s prayer to connect her home country (St James, St George, St John the Evangelist, St Catherine, St Mary Magdalene) and her new one (St Michael, St Mary Magdalene). Prayer to them often had personal associations (Michael with her triumphal entry, John the Evangelist with her mother, Mary Magdalene with Catherine of Aragon), positioning those suffrages within deeply held sentiments.

Although it cannot be said with absolute certainty (because later users of the book of hours will also have contributed to soiling), it seems that Juana used certain miniatures more than the offices that accompany them, allowing visual stimulus to prayer to guide her response to God. She had a Virgin and Child miniature added opposite one of herself at prayer and possessed the Musée des Beaux-Arts altarpiece from which the miniature was copied. Juana placed herself under the protection of John the Evangelist and prayed before the Virgin, a mother with her Child.94 She said the rosary and particularly valued traditional prayers to the Virgin.

Another aspect of hours is the relationship of text and illustrations, a point often made by those commenting on the satisfying synergy between what is heard and what is seen. However, none of this demonstrates how prayer might arise from what the eye sees on the page. It cannot be doubted that this book contains prescribed Latin prayer, determined to control Juana’s words. Yet controlling Juana’s prayer was not easy, for she could converse in Latin.95 Prayer in Latin might lead to a range of prayer responses, vernacular conversation with God, interior contemplation built on picture or soundscape, wordless prayer, or thoughts enunciated in Latin. When prayers are written and transmitted in a manuscript, particularly a beautiful one, they evoke traces of the oral prayer they previously triggered.96 Repeating the words enclosed in her prayer book, whether aloud or whilst silently moving the lips, allowing her soul to be moved to prayer by gazing on the mirror of conscience with its message that earthly beauty can only decay, and re-enacting the soul’s movements, permits uplifting towards the spiritual realm.

Juana’s book of hours allows us to catch sight of its owner, to glimpse how she might have held on to its Guardian Angel office when her world crumbled around her, and to contemplate herself in better times when she found herself incarcerated and publicly humiliated. One of the most striking insights gained from setting the hours alongside her possessions and her life is the way the hours and her possessions coincide: The Virgin and Child altarpiece, the vernicles, and the gold-enameled skull. Finding that Juana had the altarpiece of the Virgin and Child with the Flemish coat-of-arms among her possessions at the end of her life is a testimony to her deep devotion to the Virgin, expressed also in the modifications made to her hours.

Funding

This research was funded by Neil Ker Foundation Research grant, administered by the British Academy (2017), grant number NK160003.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Add. MS 10292. 1316. Lancelot-Grail. London: British Library. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_10292 (accessed on 17 April 2020).Add. MS 18851. c. 1487. Breviary, Use of the Dominicans (The Breviary of Isabella of Castile). London: British Library. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=1&ref=Add_MS_18851 (accessed on 1 June 2018).Add. MS 18852. 1486–1506. Book of Hours of Joanna of Castile London: British Library. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=2&ref=Add_MS_18852 (accessed on 1 June 2018).Add. MS 28962. 1436–1482. Book of Hours of Alphonso V of Aragon. London: British Library. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_28962&index=8 (accessed on 19 June 2018).Add. MS 35313. c. 1500. London Rothschild Hours/Hours of Joanna of Castile. London: British Library. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=2&ref=Add_MS_35313 (accessed on 17 July 2018).Add. MS 49598. 963–984. Benedictional of Aethelwold. London: British Library. Available online: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_49598&index=2 (accessed on 12 January 2020).BN MS 10095. c. 1401–1600. Libro de horas según el uso de Roma [Officium Beate Marie Virginis]. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=3 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS 17968. c. 1501–1600. Libro de horas según el uso de Roma. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=16 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS 23221. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=15 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS 236520. c. 1450–1460. Libro de sufragios. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=1 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS 6539. c. 1401–1500. Libro devocionario. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=29 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Res. 161. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=8 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Res. 178. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas según el uso de Roma. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000078392&page=1 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Res. 187. c. 1501–1599. Libro de horas. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=10 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Res. 189. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas según el uso de Roma. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=23 (accessed on 21 December 2017).BN MS Res. 194. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas según el uso de Rouen. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=20(accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Res. 197. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas, según el uso de Roma. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=5 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Res. 281. c. 1400–1500. Libro de horas. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=12 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Vitr. 21.3. c. 1401–1500. Psalterium/libro de horas. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=2 (accessed on 21 December 2017).BN MS Vitr. 24.10. c. 1450–1460. Libro de horas de los siete pecados capitales. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=37 (accessed 17 April 2020).BN MS Vitr. 24.3. c. 1501–1600. Libro de horas de Carlos V. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=36 (accessed on 21 December 2017).BN MS Vitr. 24.6. c. 1401–1499. Libro de horas, Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=14 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Vitr. 24.7. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas Osuna. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=7 (accessed on 17 April 2020).BN MS Vitr. 25.3. c. 1401–1500. Libro de horas de los retablos. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional (abbrev. BN). Availablel online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/CompleteSearch.do?languageView=es&field=todos&text=libro+de+horas&showYearItems=&exact=on&textH=&advanced=false&completeText=&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageSize=1&pageSizeAbrv=30&pageNumber=35 (accessed 17 April 2020).Cod. 1857. Hours of Mary of Burgundy. Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.Eiximenis, Francesc. 1981. Lo libre de les dones. Edited by Frank Naccarato. Barcelona: Curial Edicions Catalanes.Eiximenis, Francesc. 1986–1987. Dotzè llibre del crestià [Twelve Volumes on Being a Christian]. Edited by Curt J. Wittlin, Arsenio Pacheco, Jill R. Webster, Josep Maria Pujol, Josefina Fíguls, Bernat Joan i Mari, August Bover i Font. Girona: Col·legi Universitari de Girona/Diputació de Girona.Granada, Luis de, trans. 1536. Contemptus mundi, nueuamente romançado. Seville: Juan Cromberger.Leg. 29, Doc. 27. 1574. Testamento de Catalina de Austria, mujer de Juan III de Portugal. Simancas: Archivo General. Patrimonio Real.MS 128 G 34. 1500–1510. Book of Hours. The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/search/simple/128+G+34/page/3 (accessed on 15 January 2018).MS 134 C 47. c. 1490–1500; 1500–1525. Book of Hours. The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images_text/134+C+47 (accessed on 17 January 2018).MS 1605. 1500–1535. Psalterium Gent-Bruges. Copenhagen: Der Kongelige Bibliothek. Available online: http://www.kb.dk/permalink/2006/manus/30/eng/20+recto/ (accessed on 18 March 2018).MS 36. c. 1450–1499. Diurnale de Léon. León: Archivo de la Catedral.MS 74 G 35. c. 1440–1460; c. 1475–1500; c. 1480–1500. Delft, Masters of the Delft Grisailles. Book of Hours. The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images_text/74+G+35 (accessed on 15 January 2018).MS 74 G 36. c. 1505–1515. Book of Hours and Prayerbook (Dominican Use). The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images_text/74+G+36 (accessed on 16 November 2019).MS 74 G 38. c. 1458. Book of Hours (Hours of Jean Lallement le Jeune, Use of Bourges). The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images_text/74+G+38 (accessed on 16 November 2019).MS 76 F 16. c. 1490–1500. Book of Hours. The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images_text/76+F+16 (accessed on 15 January 2018MS 76 F 2. c. 1450–1460. Book of Hours (‘Hours of Philip of Burgundy’; use of Paris). The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images_text/76+F+2 (accessed on 17 April 2020).MS 76 F 6. Book of Hours. The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/ (accessed on 5 June 2018).MS 76 G 22. c. 1450. Book of Hours. The Hague: Koninklijke Bibliotheek. Available online: http://manuscripts.kb.nl/show/images_text/76+G+22 (accessed on 16 January 2018).MS II 2099. 1400–1500. Libro de horas. Madrid: Palacio Real. Available online: https://fotos.patrimonionacional.es/biblioteca/ibis/pmi/II_02099/html5/index.html?&locale=ENG (accessed on 12 June 2018).MS II 2100. 1450–1470. In Libro de horas. Madrid: Palacio Real. Available online: https://fotos.patrimonionacional.es/biblioteca/ibis/pmi/II_02100/html5/index.html?&locale=ENG (accessed on 10 June 2018).MS II 2104. 1400–1500. Libro de horas. Madrid: Palacio Real. Available online: https://fotos.patrimonionacional.es/biblioteca/ibis/pmi/II_02104/html5/index.html?&locale=ENG (accessed on 17 April 2020).MS Ii.6.2. Late 14th century. Roberts Hours. Cambridge: University Library. Available online: http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-II-00006-00002/1 (accessed on 17 April 2020).MS Vitr. 8. 1474–1482. Liber Missarum Reginae Elisabeth Catholicae. El Escorial: Biblioteca del Monasterio de.MS Wittert 13. 1451–1467. Livre d’heures de Gijsbrecht van Brederode. Liège: Université de Liège (Bibliothèque Générale de Philosophie et Lettres), (partial). Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2268.1/1531 (accessed on 17 April 2020).MS Wittert 26. 14th century. Livre d’heures à l’usage de Tours. Liège: Université de Liège (Bibliothèque Générale de Philosophie et Lettres), (partial). Available online: https://donum.uliege.be/handle/2268.1/1606 (accessed on 17 April 2020).Secondary Sources

- Alcalá, Ángel, and Jacobo Sanz Hermida. 1998. Vida y muerte del príncipe Don Juan. Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León, Consejería de Educación y Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Aram, Bethany. 2005. Juana the Mad: Sovereignty and Dynasty in Renaissance Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aram, Bethany. 2008. Queen Juana: History and Legend. In Juana of Castile: History and Myth of the Mad Queen. Edited by María A. Gómez, Santiago Juan-Navarro and Phyllis Zatlin. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ariès, Philippe. 1975. Essais sur l’histoire de la mort en Occident du Moyen Âge à nos jours. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Ariès, Philippe. 1982. La muerte en Occidente. Barcelona: Argos Vergara. [Google Scholar]

- Ariès, Philippe. 1983. El hombre ante la muerte. Translated by Mauro Armiño. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- As-Vijvers, Anne-Margreet W. 2003. More than Marginal Meaning: The Interpretation of Ghent-Bruges Border Decoration. Oud-Holland: The Quarterly for Dutch Art History 116: 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- As-Vijvers, Anne-Margreet W. 2007. Weaving Mary’s Chaplet: The Representation of the Rosary in Late-Flemish Manuscript Illumination. In Weaving, Veiling, and Dressing: Textiles and their Metaphors in the Late Middle Ages. Edited by Katherine M. Rudy and Barbara Baert. Medieval Church Studies 12. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 41–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Susan Groag. 1982. Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture. Signs 7: 742–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, David L. 1995. What Nuns Read: Books and Libraries in Medieval Nunneries. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 2006. Iconic Presence: Images in Religious Tradition. Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art, and Belief 12: 235–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belting, Hans. 2016. An Anthropology of Images: Picture, Medium, Body. Translated by Thomas Dunlap. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binski, Paul. 1996. Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boase, Roger. 2017. Secrets of Pinar’s Game: Court Ladies and Courtly Verse in Fifteenth-century Spain. Medieval and Renaissance Authors and Texts 17. Leiden: Brill, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuijsen, Klara H. 2009. The Masters of the Dark Eyes: Late Medieval Manuscript Painting in Holland. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Rachel Fulton. 2017. Mary and the Art of Prayer: The Hours of the Virgin in Medieval Christian Life and Thought. New York: University of Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Jennifer. 2008. Looking Inward: Devotional Reading and the Private Self in Early Modern England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Ulick Ralph. 1895. A History of Spain from the Earliest Times to the Death of Ferdinand the Catholic. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Camille, Michael. 1985. Seeing and Reading: Some Visual Implications of Medieval Literacy and Illiteracy. Art History 8: 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]