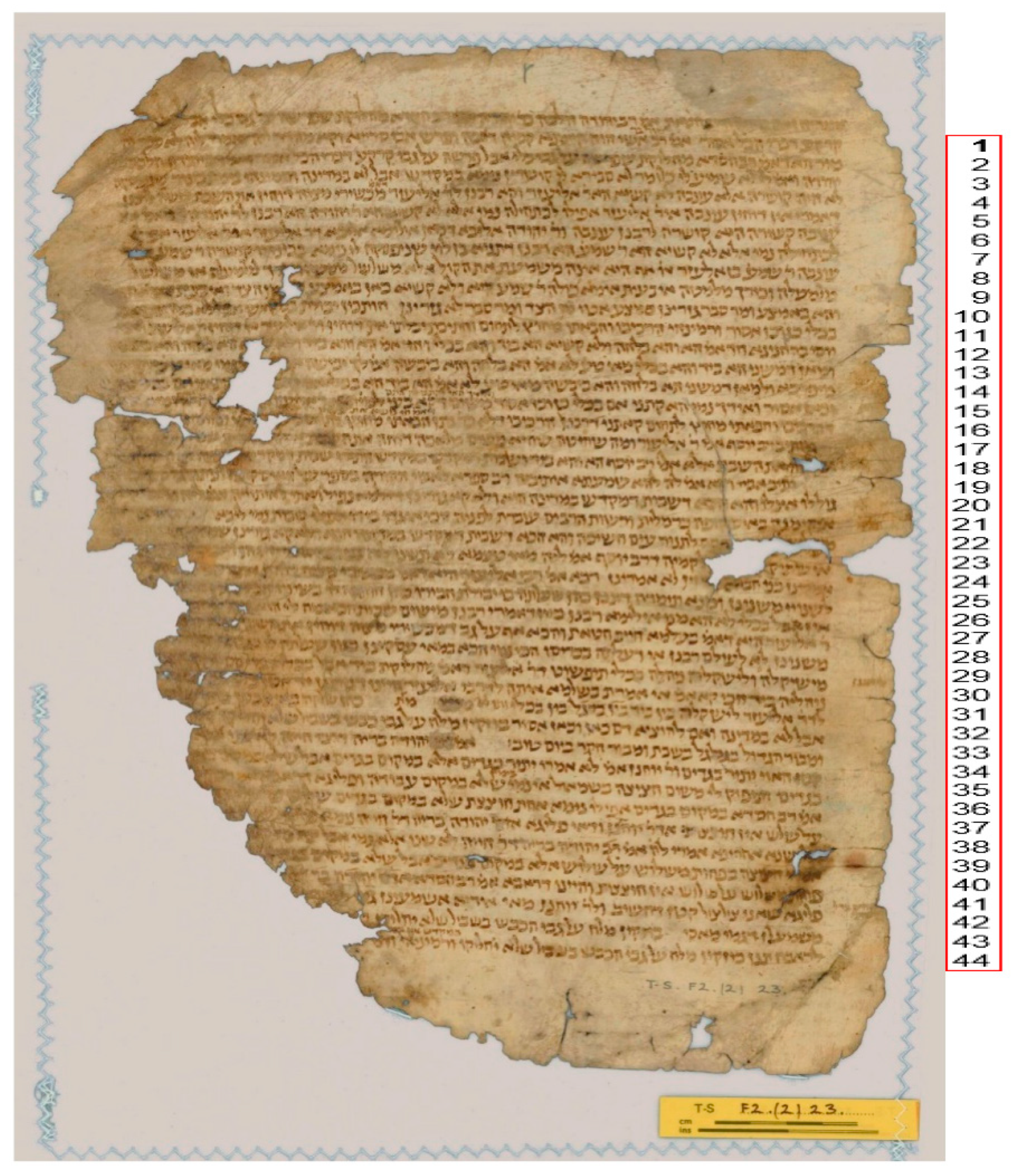

The Pronunciation of the Words “mor” and “yabolet” in a Cairo Genizah Fragment of Bavli Eruvin 102b–104a

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Text of the Printed Version (bEruvin 102b–103b)

3. Clarification of the Word “mor” (“מור”)

4. Clarifying the Word “yabolet” (“יבולת”)

5. Formation Process of the Word “yabolet” (“יבולת”)

6. The Various Interpretations of the Word “yabolet” (“יבולת”)

7. The Usage of the Word “yabolet” (“יבולת”) in the Baraitot

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amar, Yosef, ed. 1980. Eruvin Tractate. Jerusalem: Ha-Menaked. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Beit-Arié, Malachi, ed. 1987. Specimens of Mediaeval Hebrew Scripts. Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, vol. 1. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ben Yechiel, Nathane. 1955. Aruch ha-Shalem. New York: Pardes, vol. 4. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, Yochanan. 2002. The Hebrew in the Babylonian Talmud according to the Manuscripts of Tractate Pesaḥim. Jerusalem: Magnes. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Isidore. 1935. The Babylonian Talmud ʻErubin. London: Soncino Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Jacob Nahum. 1957. Introduction to Tannaitic Literature. Jerusalem: Magnes. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Jacob Nahum. 1964. Mavo le-nossach ha-mishna. Jerusalem: Magnes, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Jacob Nahum. 1982. The Gaonic Commentary on the Order Toharoht Attributed to Rav Hay Gaon. Jerusalem: Dvir. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ginzberg, Louis. 1929. Genizah Studies. New York: The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, vol. 2. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Ginzberg, Louis. 1969. Yerushalmi Fragments. Jerusalem: Makor, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jastrow, Marcus. 1967. A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli, and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature. New York: Shalom, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kafaḥ, Yosef, ed. 1963. Perush ha-Mishnayot le-ha-Rambam. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook. [Google Scholar]

- Kafih, Joseph. 1987. Jewish Life in Sanaʻ. Jerusalem: Kiriat-Sefer. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kara, Yehiel. 1980. Massorot Temaniyot be-lshon Hakhamim ʻal pi Ktav-Yad min ha-Meʾah ha-Shesh ʻEsreh. Lĕšonénu 44: 35. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Morag, Shelomo. 1963. The Hebrew Language Tradition of the Yemenite Jews. Jerusalem: The Academy of the Hebrew Language. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Morag, Shelomo. 2001. Ha-ʻIvrit be-Teman: Kavim le-Toledoteha. In The Traditions of Hebrew and Aramaic of the Jews of Yemen. Edited by Yosef Tobi. Tel Aviv: Afikim, p. 46. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Qafih, Yosef. 1989. Nikud Teʻamim ve-Massoret be-Teman. In Ketavim B. Edited by Yosef Tobi. Jerusalem: Agudat Halikhot ‘Am Israel, vol. 2, p. 931. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rabbinovicz, Raphaelo. 1960. Dikdukei Sofrim. Jerusalem: Ma’ayan ha-Ḥokhma. [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Shmuel, and Zeev Safrai. 2009. Mishnat Eretz Israel Tractate Eruvin. Jerusalem: The E.M. Liphshitz Publishing House College. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, Michael. 2002. A Dictionary of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic of Talmudic and Geonic Periods. Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Isaac Hirsch, ed. 1862. Sifra. Wien: Schlossberg. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Yeivin, Israel. 1985. The Hebrew Language Tradition as Reflected in the Babylonian Vocalization. Jerusalem: The Hebrew Academy of the Hebrew Language, vol. 4. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Yitzhaki, Shelomo. 1961. Tractate Eruvin Commentary. Jerusalem: El ha-Mekorot. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Zuckermandel, Moses Samuel, ed. 1963. Tosephta. Jerusalem: Wahrmann Books. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Rambam, Hilkhot Shabbat 9: 8, Kapach edition; Commentary of R. Hanan’el b. Shemuel on the Code of R. Isaac Alfasi on Tractate ‘Eruvin 103a, p. 604, n. 23, Klein edition, Jerusalem-Cleveland: Ofeq Institute 1996; Perush R. Ishma‘el ben Hakhmon ‘al Hilkhot ha-Rif, Eruvin 103a, Steinberg edition, Bnei Brak: Mishkan ha-Torah 1974; Rosh Mashbir, Eruvin 103a. |

| 2 | Nega’im 2: 12. |

| 3 | Nega’im 7: 13. |

| 4 | Pesachim 6: 1. |

| 5 | Pesachim 65b; Siphre zutta, Horovitz edition, Beha’alotekha 9: 2, p. 257. |

| 6 | Tesefta, Eruvin 8 (11): 20, Lieberman edition. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zur, U. The Pronunciation of the Words “mor” and “yabolet” in a Cairo Genizah Fragment of Bavli Eruvin 102b–104a. Religions 2020, 11, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11040197

Zur U. The Pronunciation of the Words “mor” and “yabolet” in a Cairo Genizah Fragment of Bavli Eruvin 102b–104a. Religions. 2020; 11(4):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11040197

Chicago/Turabian StyleZur, Uri. 2020. "The Pronunciation of the Words “mor” and “yabolet” in a Cairo Genizah Fragment of Bavli Eruvin 102b–104a" Religions 11, no. 4: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11040197

APA StyleZur, U. (2020). The Pronunciation of the Words “mor” and “yabolet” in a Cairo Genizah Fragment of Bavli Eruvin 102b–104a. Religions, 11(4), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11040197