1. Introduction

Filipinos’ entry to Japan has mainly been economic in purpose, that is, to work and earn a decent income and to provide enough sustenance for their families and relatives back home (

Semyonov 2005). Alongside this, Filipinos have brought their rich Catholic identity and heritage, eventually looking for a space to express their ethnocultural religious expressions and practices amidst the unfamiliar non-Catholic character of the Japanese nation-state, where a mere 0.3% of the entire population identifies themselves as Catholics. For

Boccagni (

2017), this religious turn of the migrants is part of their search for ‘home’ under conditions of displacement and extended mobility. Their participation in religious activities is not only viewed as a mere expression of faith but is also understood as their way to (re)connect with back home (

LeMay 2013). In the midst of a foreignness of surroundings, they find a sense of familiarity and communion in an ecclesial space as Catholics. After all, religion is a refuge among migrants in foreign environments (

Ishii 2007;

Hirschman 2004;

Komai 2001;

Ebaugh and Chafetz 2000;

Gibb and Rothenberg 2000;

Warner and Wittner 1998;

Zhou 1992;

Warner 1988;

Dolan 1972;

Herberg [1960] 1983).

Seeking respite in religion while living in a foreign land, their “search for home” is revealed as a political endeavor replete with stakes of inclusion or exclusion. Although religion’s default condition is diversity (

Grim and Finke 2012), these Filipino Catholics (FCs) are all aware of their position within the ecclesial space they want to treat their home, as ‘guests’ hosted by Japanese Catholics (JCs). Inasmuch as they are cautious of the hosts’ response, the latter is also suspicious of the guests’ presence deemed as bothersome. For

Francisco (

2014), FCs’ entry is met with a cautious plea among JCs that the latter no longer feel at home in their own church. This tension within religious space is not only within and among JCs and FCs as there are other Catholic migrants coming from Vietnam, South Korea, and India among others who have their own narratives to share. On this note, this paper takes it upon itself to articulate this sociospatial contestation between FCs as ‘guests’ and JCs as hosts who share the same faith, belong to same religion, and observe the same religio-doctrinal code while co-performing and co-existing with different cultural-performative expressions of religious faith in Japan. This paper borrows the analytical framework from Loic Wacquant’s theorization on marginality (2012) in hope of revealing traces and cues of spatial politics when rereading the historicized narrative of ecclesial negotiations between FCs and JCs. Over time, this continuous negotiation between them has constantly reproduced power relations and asymmetries; thereby locating their positions within the Bourdieusian concept of field in constant motion/flux. This fluid character that defines host–guest relations is further reinforced by the idea that power/control is not merely a tool exclusively enjoyed by the hosts as it has also showed how the guests’ actions of ethnic clustering is construed as a revolt against the top/center (

Wacquant 2012).

But how can one actually grasp those shifts and turns as well as the fluid positions and shifting locations of the interacting players within the field of negotiation without employing a heuristic device? As a tool for preliminary analysis, a heuristic device is useful in “studies of social change by defining benchmarks around which variation and differences can then be situated” (

Scott 2014, p. 305). This paper investigates proposing a map that can plot any specific historical event of interaction within a designated point in a field and mark positions of power/control or revolt/resistance of respective players. To achieve this, the paper considers borrowing the Cartesian plane as an artificial construct in mapping these phenomena of interactions and integrate into it the ideations obtained from Wacquant’s theory on marginality. After all, the logic embedded in the Cartesian plane is understood to possess a functional value as a mapping device when city maps posted in many train stations and urban plazas for example are rendered in grids marked with letter and/or numbers. Its purpose is to help its residents and tourists in locating a particular point in a geospatial area. In contrast, the use of a Cartesian plane as a mapping construct is intended towards locating positions of players within a sociospatial arena. Its functional value has shifted from mere politics of place to politics of space. It is hoped that this heuristic device on mapping locations, positions, and interactions of players within a certain field would add analytical clarity to studies that concern asymmetry of relations within a host–guest encounter plane.

2. Methodology

This paper makes use of the information gathered from the author’s two field works done and completed in separate timelines.

The first field work was completed in 2016 when the author performed a ten-month immersion in selected parish communities within the Archdiocese of Tokyo employing qualitative research tools of participant observation, interview, and document review. With 76 parishes in the entire archdiocese, the study made use of judgment (purposive) sampling in identifying the parishes for field study. The pre-set criteria in determining the sample included two main areas: (a) Filipino religio-cultural identity and (b) logistical limitation. Under the area of Filipino religio-cultural identity, the following were the sub-criteria: (a) active and organized presence of Filipino communities within the parish, (b) celebration of mass/liturgy in English/Filipino, and (c) supervision/guidance of a Filipino priest. On logistics, the field study must take into account the following considerations: (a) geographical proximity and (b) budget allocation. Given that many of these communities would only regularly meet once or twice every week, usually during weekends, there is also the predicament of schedule since the author cannot go to all or many of them in any given day since some or most of these communities would hold their activities simultaneously with other communities. In order to establish stability of presence and continuity of engagement, the author would only go to one community in a given day. With all these considerations in mind, the sample consisted of five (5) parishes: Koiwa, Matsudo, Ichikawa, Akabane, and Kasai. See

Table 1 for more details.

The author made use of an emic perspective given his ethnoreligious identification with the migrant communities and while he was not in any way a member of any of these communities, his linguistic and cultural familiarity with them provided him with a more detailed and in-depth (re)construction of their religiosity and sociocultural ethos. While bias might be an (un)intended disadvantage in this kind of insider viewpoint, the author exercised reflexivity in the process of doing research.

The second field study was performed in July 2018 and was necessitated by the appointment of Most Reverend Tarcisius Isao Kikuchi, S.V.D. as the new archbishop of Tokyo. His installation in 2017 ushered in a renewed discourse in the situation of Catholic migrants in the archdiocese as he gave paramount importance to the valuable presence and contribution of foreigners in forwarding the affairs and mission of the Church in the archdiocese. While migrant Catholics have already been recognized by the Church of Japan in the postwar era (

Macaraan 2018), the new archbishop’s multicultural orientation, having gone to mission in Africa shortly after his priestly ordination in 1986, makes him an exceptional choice to lead a Church with an increasing presence of immigrants. In fact, his deliberate choice of

Varietate Unitas (Unity in Diversity) as his episcopal motto is replete with how he envisions his mission as the head of the biggest diocese in the country. In two weeks, the author had interviews with the archbishop and a small number of Filipino priests as well as a focus group discussion (FGD) with a number of parishioners from Kasai parish.

3. The Ecclesial Existence of Filipino Catholics in Japan: A History of Negotiation

In order to articulate any fair assessment of FCs’ situated presence, it is necessary to trace its history in ecclesial space. Drawing from

Farley’s (

1982)

Ecclesial Reflection,

Haight (

2008, p. 393) attributes ecclesial existence to a “kind of social historical existence lived by a member of a Christian church”. In any analysis of church community, he believes that it is important to start by constructing a historical foundation of its ecclesial existence. “History [then] is the most basic route to determining ecclesial existence” (

Haight 2008, p. 394).

It is common knowledge that Filipinos have been visiting Japan as early as the nineteenth century as musicians. Mostly male, their brand of entertainment was admired and adored by Japanese society. Their presence though in Japan was sporadic and spotty. Even with the issuance of visas for foreigners in 1924, they were usually allowed to stay for about 15 days only (

Yu Jose 2007). This transient status hardly made it possible for them to form any community. Such impermanence however was not much of an issue with the coming of a new brand of Filipino entertainment in the late 1970s. The year 1979 marked the so-called

Japayuki Year One which was characterized by the influx of entertainers from the Philippines who were mostly women and whose work had over time been identified with prostitution and crimes (

Suzuki 2008). Such pejorative denotation associated with

Japayukis was a misnomer because that word literally refers to foreigners who are “Japan-bound” and was an adaptation of the term

Karayuki, referring to Japanese who are “abroad-bound” (

Yamatani 1985). While their contracts lasted for only six months and they had to go back to the Philippines before they could be allowed to renew for another six months (this cycle could be repeated in as many times as they wanted).

Aside from Filipino entertainers,

Shipper (

2008) contends that there was also this phenomenon of “mail-order-brides” (

hanayomes) in the mid-80s where Filipino women were pre-matched to certain Japanese from rural areas. The economic progress that Japan experienced had pushed most rural women to urban places for work thereby decreasing the likelihood of rural men to find partners who would not only be their wives but who would also be their co-help in their livelihood as farmers or fishers.

Aside from these Japayukis and hanayomes who comprised the majority of the Filipino presence in Japan, there were also some Filipino professionals who worked in the academe and corporate as well as Filipino students who were Monbusho scholars under the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

Mostly sojourners, repeaters, and returners, the residential status of these Filipinos was generally characterized as irregular, short-term, and sometimes illegal. For some though, they ended up marrying Japanese nationals, resulting in a more stable residential status. Over time, they were able to form communities in their workplaces and beyond. Eventually, their longing for religious expression found them gradually sneaking into ecclesial space. It was this that began Filipinos’ ecclesial presence.

In an attempt to diachronically sketch the ecclesial existence of Filipinos in Japan, this paper divides it into two periods with the year 2005 as the historical marker: the pre-2005 and the post-2005. Under the 2005 Amendment of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act of Japan, issuance of “entertainer” visas was largely tightened in the light of the global demand to address human trafficking resulting in a significant decrease in female entertainers entering Japan (

Macaraan 2017). The significance of this legal event has greatly defined the current status and future conditions of Filipino religiosity in the Church of Japan which this paper will delve into in the subsequent sections.

3.1. From Swording to Shielding: The Formation of a “Church-Within-a-Church” (1979–2005)

As

Japayukis working in the periphery of society, less recognized and unfairly treated, they looked into religion as their way to regain a sense of meaning in the midst of such anomic existence (

Berger 1967). In ecclesial space, they somehow felt a sense of connection to back home but the demand of their work limited their engagement in ecclesial affairs, aside from the fact that some of them were undocumented or over-extended migrant workers whose illegal residential/working status made them wary and cautious of fully and actively participating in many religious activities for fear of arrest and deportation (

Shipper 2008).

The early years were difficult as almost all of the parishes in the archdiocese only offered Sunday mass in Nihongo and Filipinos would only be attending it without really understanding anything from it. For them it was all they could do given the absence of recognition that was given then to FCs. With the increasing number of FCs in the 1980s, some parishes opened up English masses to cater to foreigners. The provision for an English Sunday mass however was at the discretion of the parish priest. Given the lack of English masses, transparochialism among the FCs proliferated during this time although, to a lesser extent, it has remained an obvious practice even until today. They never identified themselves as members of any particular parish as they “hopped” from one parish to another in search of an English mass. The only basis of attending mass then was linguistic medium. This tendency of migrants to identify themselves not to their juridical parish but to that which they can culturally identify with is what

Janicki (

1985) refers to as “personal parish, determined not by place of residence of the parishioners but by their affiliation based on rite, language or nationality” (

Bankston and Zhou 2000, p. 460).

Given the illegal status of some of these Filipino entertainers as well as the fact that weekends were their most labor-intensive workdays, their presence in ecclesial space was scarcely significant. If ever they would take part in many of these religious gatherings,

Shipper (

2008, p. 1) cited a powerful narrative from Lisa Go in her 1994 published interview in Japan Christian Activity News.

At the front pews you will see the ‘legitimate’ Filipino community—the embassy people, the students on Monbusho scholarships, the spouses of Japanese nationals, then the male migrant workers, who are engaged in ‘decent back-breaking labor’. Crowded by the door are the women who work in the sex industry, the last to arrive and the first to leave. Readers and leaders are almost always the students. Although coffee or tea and cookies are served after mass, for fellowship, only the ‘legitimate’ members of the community remain.

While this observation seems to portray an inner conflict among co-ethnics, the author finds this construal rather incredulous. In his interview with a number of FCs, the more prevailing reason for such spatial placement in the early years of ecclesial existence was mainly due to the nature of their job as entertainers. Although random raids and arrest by authorities were still reasons to fear, these Filipino entertainers felt generally safe and secure while inside a church. The only reason that they would come in late and leave early was the fact that weekends were their busiest workdays. They positioned themselves by the door only because they did not want to disturb the celebration of the mass as they arrived late and left even before the mass was completed. Going home from bars and clubs in the early morning of Sunday, they had to return to work in the evening only after spending the entire daytime sleeping and recovering from the previous night’s work shift. They barely had enough time to even mingle with their co-ethnics after mass for tea or snacks as they had to immediately go back home and prepare for another graveyard work shift.

In an interview with Edna, a Filipino lay leader, she recalled how in the beginning, Filipinos were only allowed to use the church resources very limitedly as many JCs found FCs noisy, untidy, and messy. This is similar to how

Spencer (

1992) would categorize Filipino laborers in Japan as

kitsui (difficult),

kiken (dangerous), and

kitanai (dirty). She even recalled an instance where a number of Filipinos were caught selling counterfeit materials in Akabane church grounds. That was one of the reasons, she recalled, why Akabane parish decided to stop having Sunday masses in English or Filipino to ward off Filipinos from communing in parochial grounds, to a certain extent.

The introduction of Filipino (Tagalog) as a linguistic medium on a (Sunday) mass would only be possible with the presence of a Filipino priest as mass presider. Despite the relative presence of foreign priests, they were mostly Westerners who could not preside for them a mass in Tagalog. Because of the cultural and linguistic inability of Japanese priests to provide pastoral care to migrant Catholics, “it is only by inviting a priest from outside to come to smaller churches to provide occasional non-Japanese mass for immigrants” (

Mullins 2011, p. 182). In the early 1990s, Nida, a Filipino lay leader from Kiyose parish, recalled her chanced encounter with the Japanese parish priest of Kiyose back then. She was just outside the church then and was talking with some of her Filipino friends after attending a Nihongo Sunday mass when the Japanese priest approached them. It was in this specific encounter where they were instructed to look for a Filipino priest to preside over a Tagalog Sunday mass to cater to the increasing number of FCs in his parish. He promised to lend the church space for them in a Sunday afternoon for their Tagalog mass while JCs would keep their original schedule of Nihongo mass in the morning. It was for Nida a critical moment in the eventual growth of Filipino communities in many parishes in the archdiocese. Soon, a number of religious congregations in the Philippines sent Filipino priests to missionary work in Japan. Interestingly, a number of these priests had gone beyond their religious obligations to Filipinos as they were also involved in helping the migrants in their legal, psychological, and economic concerns (

Komai 2001).

While FCs were granted space to use for their religious activities, they were only allowed to perform such activities after the JCs were over and done with theirs. In almost all parishes that had allowed Filipino/English Sunday masses, the mornings were for the JCs and the afternoons for the FCs and other ethnics. When asked about this set-up, one of the Filipino priests whom the author interviewed shared that such temporal-spatial separation was intended to provide an exclusive space for both ethnics to perform their religious and parochial obligations without disruption/interruption from others. The basic rule of engagement had become: mind your own business as we mind our own. As long as FCs behave and comply according to parochial policies and requirements set by the parish council who were (entirely) composed of JCs, the FCs were allowed space to perform their own religious rituals in their own cultural way.

As a “Church-within-a-Church”, some Filipino lay leaders started to introduce various lay movements like

El Shaddai and Couples for Christ (

Mullins 2011). They also somehow recreated the organizational and operational dynamics of JCs by electing their own officers both in parochial and archdiocesan levels, organizing cultural festivals within parish grounds, building networks among various Filipino parochial communities, setting up table fellowships after mass and religious activities, and initiating their own recollections, prayer services, and pilgrimages. One notable example is the group called MICHIKOTO United which is an inter-parochial network of Filipino religious communities from parishes of Matsudo, Ichikawa, Koiwa, and Toyoshiki. Under the guidance of a Filipino priest, this group is not governed by any parish and is deemed transparochial although maintains a close coordination with respective parish priests of the four parishes.

During this period, many of these Filipino women had married Japanese men. And as their status became more stable, their availability and obligation to their own religious communities also expanded. With expanding religious agency, as reinforced by a supportive ethnic community and a tolerant host community, these FCs were able to exercise their voice and cultivate what

Shah (

2013) refers to as “spiritual capital”. While parish councils were populated by JC lay leaders, there were few occasions that they would invite a representative from the FC community to sit in the council, except as mere spectator and without much political capital. The purpose of them being invited was mainly for the transmission of news, updates, and policies of the parish down to the FCs.

From mid 1990s to early 2000s, while there had been some traces and cues of acceptance and openness from the hosts, the general treatment of FCs and other ethnics was still within the “guest” categorization. In 1997, the Archbishop of Tokyo Cardinal Peter Seiichi Shirayanagi said,

Among the men and women who come to us from the Philippines and Latin America there are many, many people with the same Catholic faith as ourselves. Are we [Japanese Catholics] to treat them [foreign migrants] merely as guests in a church where Japanese are the center of affairs or accept them as brothers and sisters of the same Church family, with membership and responsibility in the same Church community as ourselves?

Two issues can be deduced from this statement: (1) the “guest-identity” of FCs in Japan as well as (2) the desire of the archdiocesan center to integrate these foreign Catholics in the Church of Japan. It is this confused state of direction that would mark the beginning of the third millennium until the present. How would the Church of Japan particularly the Archdiocese of Tokyo move towards fully integrating the foreign Catholics to the Church while dealing with the pervasive and entrenched guest-identity accorded to them by the hosts?

3.2. The Vision of a Multicultural Church: From “Guests” to Missionaries (2005-Present)

The tighter immigration laws since 2005 significantly diminished the entry of female entertainers from the Philippines as stricter measures and requirements were put in place primarily to counter human trafficking (

Kondo 2015). It implicates the current Filipino religious communities in terms of continuity and longevity as many of today’s members are ageing and their bicultural kids have not embraced the same religious fervor of their Filipino mothers. Without the infusion of new and younger members, demographic sustainability remains a predicament. The same however is also a concern among JCs.

Even with the signing of the Japan–Philippine Economic Partnership Agreement (JPEPA) in 2006 that offered Filipino healthcare professionals work in Japan, there has not been a significant number of Filipino nurses and caregivers coming in for employment which could have largely augmented the ageing FCs as new and young members.

Calunsod (

2016) cites Japan’s difficult working conditions and stressful psycho-social environment as reasons for the low turnout of Filipino takers. In addition,

Kingston (

2011) thinks that Filipino nurses are still attracted to working in countries like US, UK, Australia, and Canada owing to better salary offers and less stringent requirements for obtaining job security. While there has been a steady arrival of a few Filipino students and male contract-based workers, they are not expected to positively impact this predicament given their residential status as temporary and short-term. Students usually return to their country of origin after completion of a degree and these male workers are only allowed three months to a year of contract, notwithstanding the fact that even Sundays are workdays for many of these men who are generally employed in the construction sector.

With an endangered demography struggling to infuse new and younger blood, the urge is to (re)introduce the youth (back) to religion. It is argued that as bicultural youth, their predicament is religio-culturally nuanced. Their disconnected religious existence must be traced back from when they were still those kids who were brought along by their Filipino mothers in church gatherings to when they started to increase their awareness and identification with Japanese culture as they learned how to both adapt to Japanese social ethos and adopt cultural cosmologies (replacing, in the process, anything that is Filipino with their father’s home culture of Japanese). Growing up, they had a certain fondness with the sights and sounds of Filipinos’ expressive religio-cultural performances while in the church but over time, the linguistic barrier caught up with them as they felt confused and somehow alienated due to their non-familiarity with Filipino language. It did not help too that as they entered junior high school, even Sundays were allotted for their school clubs (

bukatsu/kurabu). Eventually, Tagalog (Filipino language) mass has become just a noise to them as they grow alienated from their mother’s native language. Interestingly, they find attendance to Japanese mass less attractive too given the lack of expressiveness and warmth that they used to see and feel in Filipino masses and gatherings. In the end, they feel no sense of belongingness to any of them as they would rather stay at home on a Sunday or just be elsewhere with their friends.

Macaraan (

2017) proffers the idea of providing a separate distinct space for these bicultural youth to express and articulate their religiosity and faith in terms of

Kymlicka’s (

1995) egalitarian approach to multiculturalism. As their status as bicultural is a product not of their own choosing, the Church must provide special accommodations to them like a more religioculture-specific pastoral plan for them among others. If any vision of a multicultural Church in Japan is in the offing, it cannot but include the plight of the bicultural youth.

The discourse of a multicultural Church through the integration of migrant Catholics has been consistent in many pronouncements of the Church hierarchy. The pastoral direction towards an inclusive and welcoming Church is primordial and paramount. In the website of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Japan (CBCJ), the opening statement of the Catholic Commission of Japan for Migrants, Refugees, and People on the Move, headed by Bishop Michael Matsuura, states its mission to work “for the realization of a multicultural society based on the Gospel…” (

CBCJ n.d.)

Archbishop Kikuchi in an interview last November 2019, weeks before the visit of Pope Francis in Japan, admitted the difficulty of evangelization in Japan mainly due to the non-Catholic situation of the mainstream society. Despite this however, the archbishop has singled out the role of the foreign Catholics who have settled in Japan and have built their homes mostly in rural areas thereby acting as agents of evangelization to places where the Church had never had an opportunity to preach (

Nerozzi 2019). In addition, he wanted an end to the mindset of treating them as mere “guests” in ecclesial space. Instead, he forwarded a need to (re)awaken in them their vocation as missionaries. “Pastoral care for foreign nationals in the Japanese church is not merely a service to welcome [guests], but rather a duty to make them aware of their vocation as missionaries” (

Nerozzi 2019). From being guests to becoming missionaries, Kikuchi’s vision is not only a challenge for the pastors and hosts but also for the foreign Catholics themselves, including the FCs, to embrace this identity and enact a more active role in the mission of evangelization. Kikuchi believes that as long as these foreign Catholics would be labeled along the category of guests, the best the hosts can do is merely to welcome them and for the foreigners to merely fit in. Welcoming them is not enough; it is necessary to instill in them that they have a missionary vocation.

When the author interviewed the archbishop last July 2018, the latter spoke about the urgency for the Filipino mothers of these youth to help their kids reinvigorate their Christian identity, after all, many of these young people are baptized Catholics since they were infants. A mothers’ missionary task starts at home; in her household. Since many of these Filipino mothers have already been largely accustomed to Japanese language and culture, the urge is to accompany their kids in attending the Japanese mass; in a religious gathering that these young can understand and can construct meaning thereto. Bringing or expecting them to take part in Filipino masses may not be ideal anymore. In a study by

Ebaugh and Chafetz (

2000, p. 119) of ethnic religious congregations in America, they notice that “recreating the ethnic ambiance of the old country… including the extensive informal and formal use of the native tongue… alienates their Americanized offspring”.

4. The Host–Guest Interplay in the Light of Wacquant’s Theory on Marginality

The historicized narrative of negotiation between JCs as hosts and FCs as guests would be further articulated under the lens of

Wacquant’s (

2012) analytical frame on marginality. Utilizing Wacquant’s four-characterization of an urban ghetto (stigma, constraint, spatial confinement, and institutional encasement), this paper attempts to highlight the exchange of swording and shielding that these players have used in the course of their interaction and encounter.

Wacquant’s (

2012) interesting insight that urban ghettos’ clustering over time is an act of revolt/resistance against the dominant group shows that in any interplay of players with asymmetrical positions, both possess tools of marginality: the sword of the dominant and the shield of the subordinate.

This is important in order to show that FCs, while generally portrayed as subordinate given their identity as guests, have also contributed to their marginal status and any narrative of portraying (or glorifying) them as victims would not at all help in any attempt towards the realization of a multicultural Church in Japan. While their seclusion was initially proffered by JCs’ unwelcoming position and cautious stance, it has been maintained over the years because FCs have grown convenient and comfortable with it. Their shielding strategy has become an opted seclusion after all. By unmasking this ideology of victim-narrative, this paper believes that it would eventually be beneficial towards realizing their duty as missionaries and not just their identity as victims in the guise of the label “guests”.

First, the stigma that characterizes FCs in Japan consists of various layers; they are foreigners (race) employed mostly in less attractive jobs (work) and are members of a minority Church as Catholics (religion) in a non-religious country. In terms of employment,

Yoder (

2011, p. 51) speaks of the stigma attached to women working in the sex industry…” like the

Japayukis because their way of earning money is considered deviant. In terms of religion,

Mullins (

1996, p. 139) notes how “even today, many Japanese regard Christian religion as foreign or

batakusai (literally, smelling butter)”. Even the Japanese word for “church” (

kyokai), which literally means “teaching association, …[it] reinforces the idea that Christianity is

yosai, technical and moral Western learning [that]… perpetuates the notion that Christianity is a foreign religion” (

Suggate 1996, p. 73).

Second, Filipinos in Japan have long been constrained culturally and religiously. During the opening of the 2016 Philippine Festival in a park in Tokyo, a Filipino priest was about to say an opening prayer when he was disallowed to use microphone due to prohibition of any religious demonstration in public places. Reproduced and extended in sacred space,

Zarate (

2008, p. 35) notes this constraint in the lack of trust that the host gives to the FCs.

Even if they [Filipinos] are Catholics and have the right to use the church and its facilities, they are just given time to use them under certain conditions, as to say, ‘We lend you our church. Use it well, but not as if you own the place’. They are not trusted to use the place well and are even put under a bias that they would never be able to leave the place clean.

The employment of constraint may also be because Filipinos are completely different to Japanese, an anti-thesis or an alter ego. “People from the Philippines are usually imagined as anything but Japanese” (

Faier 2009, p. 7). Filipinos’ cultural and behavioral expressions are at most times constrained by the cultural sensibilities of the host group especially when those expressions are deemed contradictory, scandalous, and inimical to Japanese cultural ethos.

Mullins (

2011, p. 185) shares snippets of a lecture by Dr. Maria Carmelita Kasuya, a Filipino lay leader in Tokyo, detailing how Filipinos’ religious behavior during liturgical celebrations are marked by spontaneity, warmth, and liveliness as opposite to Japanese’ formality, refinement, and silence.

The Japanese services seem very formal and orderly and tend to use older hymns, whereas Filipino Catholics are more accustomed to new songs and music in services. Whereas the ‘passing of the peace’ in typical Japanese services consists of a polite bow or nod in the direction of one’s neighbors, Filipino members are much more expressive and often shake hands or embrace and often perceive Japanese services as lacking in basic human warmth. And where Japanese members tend to be rather refined and educated, many Filipino members lack a solid education or instruction in the faith.

Third, their religio-cultural practices have long been spatially confined more prominently in the pre-foundation years of these Filipino church-based communities. Without an ecclesial space to practice religious beliefs, early Filipinos would make do of house-to-house evangelization and private gatherings. On some occasions, even the night bar workplace was adorned with religious statues/images especially if a Filipino owned or managed the bar (

Faier 2009). While today’s FCs are allowed to organize their own religious activities in parishes and have gained considerable recognition from the JCs, their religio-cultural gathering is still confined to a schedule that does not disturb or infringe into Japanese spatial–temporal activity. JCs usually hold their Sunday masses in the morning while most FCs’ masses are in the afternoon. Curiously, this spatio-temporal gap hides an interesting case of “lubricated friction” (

Macaraan 2016) when Filipinos’ ‘insubordination’ or ‘revolt’ is mistaken for an ideal compliance; preventing hostile tension by lubricating its cross-interaction with something acceptable to both groups, while maintaining their own religio-cultural expressions.

Fourth, the institutional encasement of FCs is construed as a necessary effect of continuous stigmatization, constraint, and confinement. Pushed into the periphery of both the secular and sacred space, they have since thrived and have gained a sense of autonomy; organizing themselves “with a distinct and duplicative set of institutions enabling the group thus cloistered to reproduce itself within its assigned perimeter” (

Wacquant 2012, p. 33). When early years witnessed the social control used by Japanese unto Filipinos as a kind of external closure, Filipinos subtly reinforced their communal ties and camaraderie through internal bonding. This sword/shield binary is what

Wacquant (

2012) refers to as the Janus-faced character of a ghetto with sword identified as a piercing tool (figuratively) used by the dominant group in excluding the other while the shield represents the eventual reorganization of the constrained group to protect itself from the dominant. He further argues that they co-exist in a plane that is in constant shift, more like a balance scale, whose interaction is characterized by inequality. What transpires is a hierarchical and non-homogenous interaction of these two groups where certain historical situations and conditions provide cues for how each group maneuvers and struggles in pursuit of desirable resources.

Table 2 below provides a summary of how these four characteristics of an urban ghetto are manifested in FCs.

5. The Techne of Cartesian plane and the Episteme of Wacquant’s Theory on Marginality: Towards a Proposed Heuristic Device

Over the course of time, this dialectic of external hostility and internal affinity were both exclusionary strategies used by both JCs and FCs in their desire to be separate and disconnected. However, recent situations of ageing demography and the lack of religiously-interested youth have made both ethnoreligious groups susceptible to possible extinction and further social irrelevance. By this time however, the shielding resource of the FCs had become more powerful than the swording capacity of the host. By late 1990s, the host had become more open for integration. Amid long years of elective seclusion and ethnic clustering, Filipinos had since formed a stronger communal bond and had made any integrative attempt a calculated and cautious decision, at least on the part of the FCs. For a time, they have enjoyed this “protective and integrative device insofar as it relieves its members from constant contact with the dominant and fosters consociation and community-building within the constricted sphere of intercourse it creates” (

Wacquant 2012, p. 25).

However, times have changed. The Church of Japan has been calling for a more integrative Church and an ecclesial space marked by improved and inclusive inter-ethnic communal relationship and unity. This is an initiative to counter the effects of parallel ethnic church dynamics that had defined the Church for many years. From this, one can surmise the shift from an arena of exclusive contestation to a domain of inclusive negotiation, but the ambiguity of this full integration stands (

Macaraan 2017).

In this interplay of players, positions are fluid and shifting and it is the purpose of this paper to propose a heuristic device that can be utilized in mapping and locating these positions by plotting a specific historical event/phenomenon in a field of social interplay. The Cartesian plane will provide the artificial construct but its inherent logic would be tweaked by incorporating

Wacquant’s (

2012) theorization on marginality. The

techne inherent in the Cartesian plane is extracted while recalibrating its inherent

episteme with the ideation proffered by Wacquant. Fused together, this

techne/episteme synthesis characterizes the operational logic of the proposed heuristic device.

A Cartesian plane is a two-dimensional graph that is named after the French philosopher and mathematician Rene Descartes who published this idea in his work

La Geometrie in 1637 (

Bix and D’Souza 2016). The

techne that is extracted from the Cartesian plane is substantially its operational technique to locate positions within a plane using coordinates from two axes (x,y). The grid-like structure that can be gleaned upon the Cartesian plane may be useful as a mapping device in locating a certain entity and its movements across a vast plane or field. Characterized as coordinates, one’s position is identified by its distance from the point of origin (0,0) along the horizontal x and vertical y axes. Every position, location, and movement is measured from the point of origin (0,0). The further one goes to the right of the x axis, the more positively it is numerically categorized and the further towards left it moves, the more negatively it is numerically valued. Similarly, the higher it goes up the y axis, the more positive its numerical value becomes while the lower it goes down the same axis, the more negatively it is numerically characterized.

The mapping orientation proposed in here is not understood as a cartographic sketch or a scale model of the distribution of people in a certain geospatial perspective but the kind of mapping that locates positions of interaction and interplay between two ethnic communities within a field defined critically in terms of power relations, ideologies, and hierarchies. For

King (

2019, p. 336), mapping is an important part of the language of migration as it provides a “concrete spatial insight into their [migrants] ongoing identification processes as people traversed pluri-ethnic and linguistic zones and frontiers, but at the same time profoundly modifying those cultural spaces.” While King primarily speaks of this in terms of migrants’ geographical mobility, the author construes its applicability too in terms of migrants’ spatial mobility as they negotiate with various sociodemographic and religio-cultural constructs in their lives.

In 2009 at the Roth-Symonds Lecture in Yale School of Architecture,

Wacquant (

2010, p. 165) characterizes sociospatial seclusion as a process whereby social categories and activities are “corralled, hemmed in, and isolated in a reserved and restricted

quadrant of physical and social space” (italics emphasized). In his attempt to distribute the ideal-typical forms of sociospatial seclusion, he makes use of familiar components in the Cartesian plane by rendering it in “

two-dimensional space defined by those

two axes…” (italics emphasized) (

Wacquant 2010, p. 165). In

Wacquant’s (

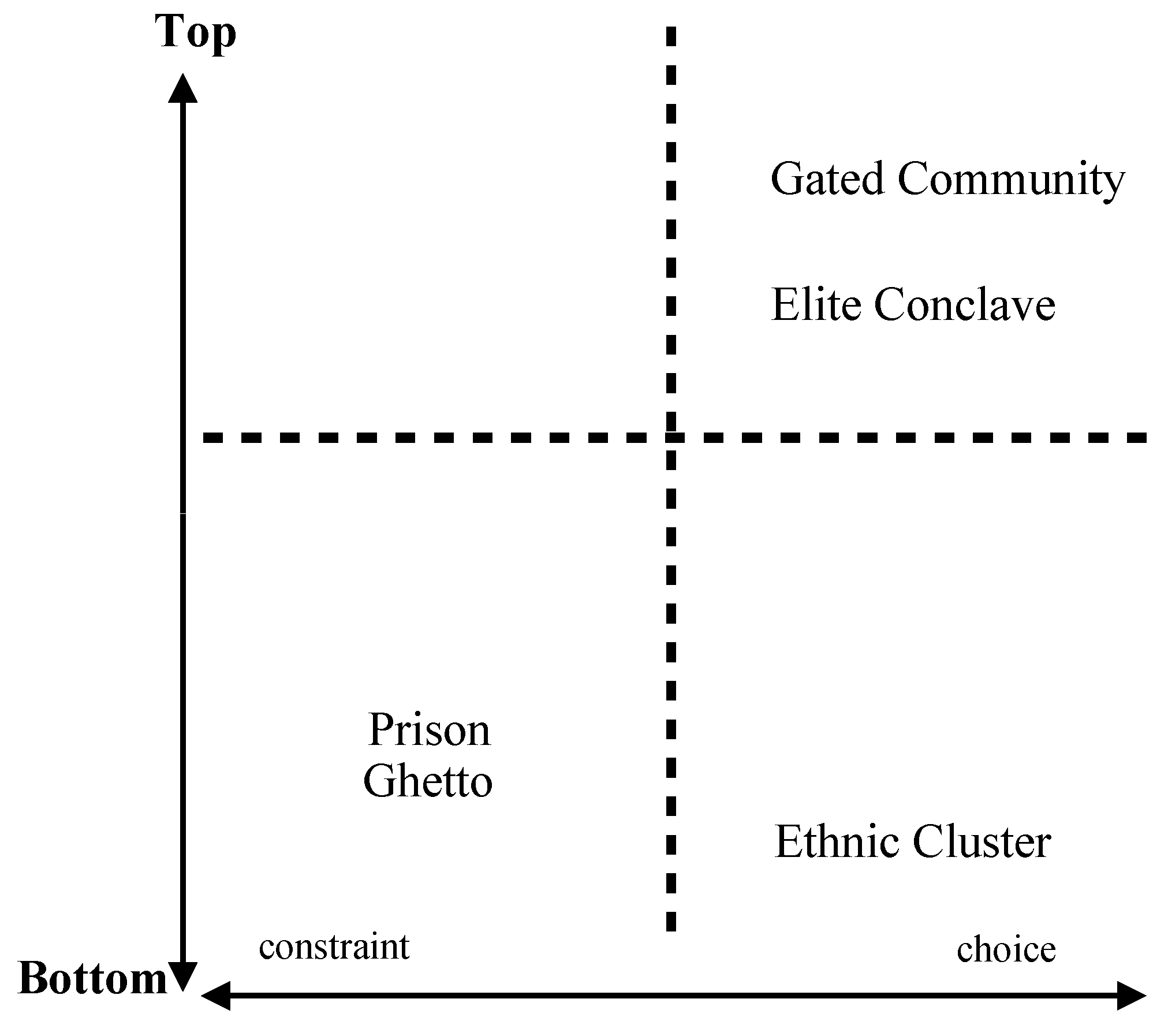

2010) figurative rendering of his ideation of sociospatial seclusion in urban settings (see

Figure 1), he makes use of quadrants and axes but the functional value of it as a heuristic device is mainly to account for the different typologies of sociospatial seclusion in terms of two dimensions: (a) whether the social hierarchy is based on class, ethnicity, or prestige/rank and (b) whether the sociospatial seclusion is elective (choice) or imposed (constraint).

The functional value embedded in

Figure 1 is however limited to the identification of what particular form of sociospatial seclusion is embodied. It is not intended to plot events of interplay between two players and locate their positions within the field of social exchange. Utilizing the

techne of the Cartesian plane, particularly its ability to map locations and movements using coordinates, the proposed heuristic device foregrounds it with the

episteme of Wacquant’s ideation on strategies of inclusion and exclusion illustrated in his ideation of the ghetto as Janus-faced, possessing a double-sided trait as a sword (for the dominant) and a shield (for the subordinate) (

Wacquant 2012).

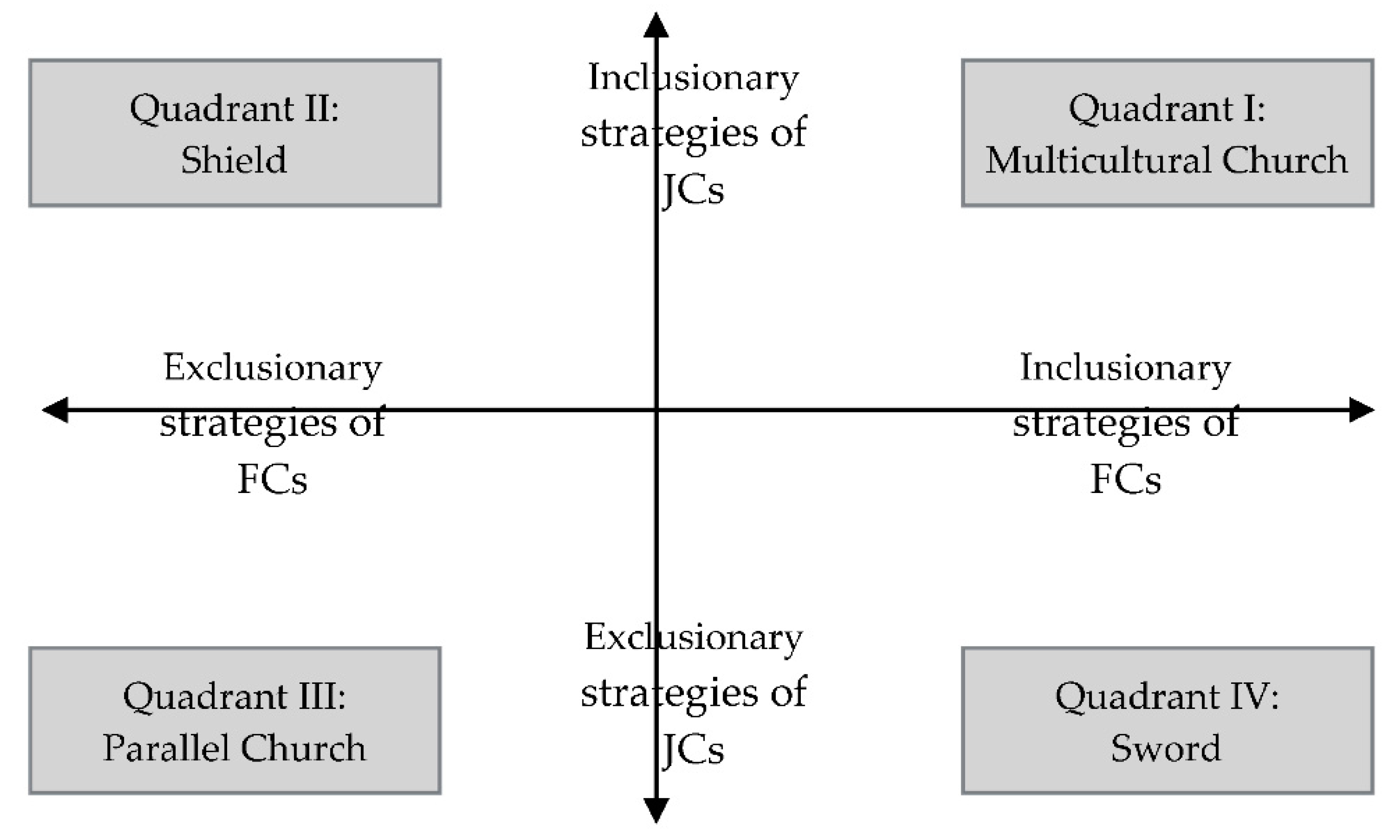

Foregrounding the

episteme of

Wacquant’s (

2012) logic of inclusion/exclusion in the Cartesian plane, the y axis would refer to the exclusionary/inclusionary tendency/attitude of the JCs as the host group while the x axis would relate to the FCs’. Positive integers refer to inclusionary acts as the negative numbers to exclusionary acts. Quadrant I (+,+) is named “Multicultural Church” which encapsulates the vision of the Church of Japan in relation to its call for the integration of various ethnic church communities. Quadrant II (−,+) refers to the “Shield” which highlights the exclusionary tendency of FCs despite the inclusive initiative of the host JCs. Quadrant III (−,−) speaks of the “Parallel Church” imagery where both the JCs and FCs mutually resort to exclude one another and prioritize one’s own ethnic group’s being. Quadrant IV (+,−) is the “Sword” where the emphasis is more on the constraining and restricting tendency of the host group than the attempt of the migrant group to belong and be recognized. To better visualize this reappropriated Cartesian plane, see

Figure 2 below.

When FCs’ ecclesial history is plotted in this reconfigured Cartesian plane, the general mobility of FCs’ historicized narrative with JCs in pre-2005 is significantly found within Quadrants 4, 3, and 2. In the early 1980’s when FCs were generally unrecognized, they were barely provided with any organized institutional pastoral care (

Macaraan 2018). Their participation in the mass was insignificant. When FCs began to form communities and Tagalog masses gradually became a regular fixture in some parishes, JCs’ exclusionary strategy placed a definitive borderline around the FCs by having their religio-ethnic affairs in a separate spatiotemporal schedule, and this can be construed, at least initially, as a seclusion that is imposed upon the FCs by the JCs. The incidence in Akabane church too where they were disallowed to commune is an example of an imposed seclusion by the hosts. These events can be plotted in Quadrant IV. When FCs over time grew conveniently secluded in their own space, recreating the organizational structure and operational activities of the host group, it shows ethnic clustering marked by an elective seclusion. The formation of MICHIKOTO United and the perpetuation of linguistic-centric devotions like block rosary and house-to-house evangelization only exclusively by and for Filipinos are examples of shielding strategy employed by FCs and are hereby plotted in Quadrant II. The eventual evolution of parallel church imagery in Quadrant III is construed as a by-product of the binary strategies of ghettoization by both the JCs and the FCs. Their mutual exclusivity over time has resulted in a convenient indifference and relative detachment to each other’s religious activities and lifeworld.

While the post-2005 era would still manifest a parallel church imagery, there is already a more profound awareness among both groups of their demographic crisis due to disinterested youth and ageing members as well as the institutional call towards a more inclusive Church. Most parishes have already acknowledged the presence of these foreign Catholics and a good number of them have given these ethnic communities significant representation in parochial councils and the management of ecclesial affairs. There is also a considerable increase in contact spaces between and among them when in parochial grounds. While mass schedule is still separately held, some parishes have regularly organized (at least annually) a so-called “international mass” infusing ethnic songs and music as well as translating some prayers and responses in the dialect of other foreign Catholics. During this gathering, both Japanese and non-Japanese faithful attend the mass together, providing an enriched awareness of each difference and giftedness. It is therefore safe to assume that the post-2005 era is largely located in Quadrant I.

What this mapping has shown is the directional orientation and mobility of a particular group (guest) relative to another group (host) and vice versa. From early dynamics of exclusionary tendencies to recent actions towards inclusion, the map acts as a visual tool that plots historical events within the field of exchanges and interactions, revealing hierarchical identities, power-play relations, and negotiations. The mapping can also reveal communicative exchanges between two or more groups in interplay; improving how one reads through the historical existence of a particular group in relation with other groups. In doing so, the mapping provides more informative data for policy-makers, persons in authority, field researchers, and field players towards realizing objectives and goals of any institutions or structures.

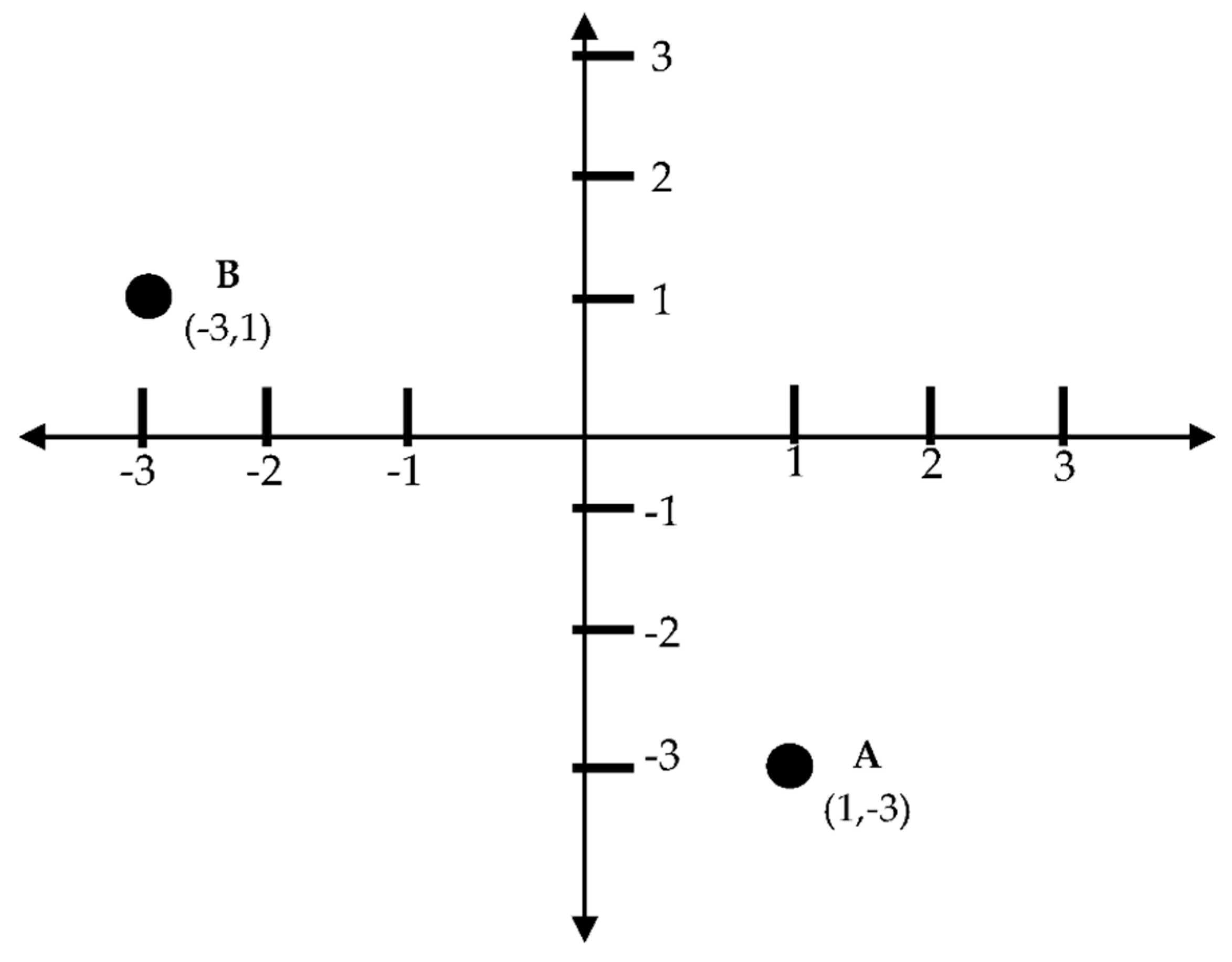

The proposed heuristic device can further be improved with the utilization of numerical points that can quantify both the extent and degree of exclusionary or inclusionary tendencies of groups in a study. Although this is something for another paper or a suggested improvement employing a statistical framework, the numerical valuation that this Cartesian plane inherently possesses is significantly helpful in facilitating a better and clearer exposition of spatial positions and locations of players within a field of exchanges. Assigning negative and positive points in both axes, with the point of intersection given a numerical value of (0,0) (the farther one’s location is to the point (0,0), either in x or y axis) reveals the extent of inclusivity/exclusivity of a certain group. The farther it goes to the top/right of the axis (positive integers) the greater the degree of inclusion while the farther it goes to the bottom/left of the axis (negative integers) indicates an increased degree of exclusion. To numerically plot a certain historical event relative to players’ interaction, norming criteria must be set in place at the onset. In plotting, for example, the event where Akabane parish stopped Filipino gathering in its parochial grounds due to FCs’ inappropriate (and to certain extent illegal) activities, within a scale marked from −3 to 3 (−3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3), JCs’ exclusionary action is clearly shown to a degree that is strongly manifested (−3) while FCs’ general sentiment of disappointment with their co-ethnics’ behavior manifest a desire to be included (1). Hence, the Akabane incident (A) can be plotted in Quadrant IV with coordinates (1,−3). The formation of MICHIKOTO United, meanwhile, can be understood as a strong manifestation of FCs’ exclusionary tendency to be and have on their own (−3) despite the relative openness of the JCs at this juncture although tolerated and permitted by Japanese parish priests of the four parishes (1). For MICHIKOTO United (B), it can be plotted in Quadrant II with coordinates (−3,1). To illustrate, see

Figure 3 below.

6. Conclusions

What this paper has proposed is a heuristic device that may prove helpful in any preliminary analysis of communicative exchanges between and among ethnocultural groups whose historical narratives co-exist and inter-play within a field of hierarchical power relations. By extending any historicization of ethnic group relative to other ethnic group/s from merely narrating it to plotting their spatial positions and locations within the field characterized by relations of power and capital, one would be able to better grasp directional tendencies over the course of time, which is particularly helpful not only to researchers but also to policy-makers where studies on pluralist societies are usually entrenched within the ideological vision of integration and communion.

The discourse of sociospatial seclusion, enlightened by

Wacquant’s (

2012) study on urban ghettos has uncovered and unmasked the so-called ideology of victims, particularly its capacity to resist/revolt through elective ethnic clustering as its ideological strategy to be exclusive. What can be drawn from

Wacquant’s (

2012) ideation is that in any phenomenon of ghettoization, both the dominant and the subordinate have tools that each can exercise either by swording of the dominant or by shielding by the subordinate. Indeed, the dominant may have pushed the subordinate towards seclusion but the perpetuation of their seclusion over time is highly likely brought about by the elective decision of the subordinate to remain ethnically clustered. In short, sociospatial seclusion is double-sided.

In reconstructing the victim-identity of FCs in ecclesial space, this paper has brought a renewed discourse on the role and agency of FCs towards the vision of a multicultural Church in Japan. Archbishop Kikuchi may be right in his challenge for the FCs and other foreign Catholics to embrace a more proactive role in the Church of Japan not anymore as “guests” but as missionaries. If FCs’ clustering is maintained and perpetuated mainly by their power to opt, choose, and elect—tools that have ideologically provided them enough space to resist the dominant—perhaps, FCs must evaluate their role and appreciate their agency as missionaries, and not merely as “guests” trying to fit in and comply.

When this ideation of Wacquant (episteme) is embedded in the mapping utility (techne) of the Cartesian plane, it is possible to plot certain historical events of exchanges that would prove useful not only in locating shifting positions but also the routes it takes over time. The proposed heuristic is still in its nascent stage. Quantitative analysis may be infused into it in order to better equip this device with more sophisticated analytical processes and evaluative mechanisms particularly when exploring and understanding asymmetrical relations of players/actors/agents located within a host–guest relationship. This heuristic device develops, not only a historical exposition of encounters in a temporal-linear category, but also its functional value as a mapping tool that can plot locations and positions of players as well as plot historical events within a sociospatial field characterized in terms of capital, power relations, and hierarchies. Information that can be drawn from this heuristic device could be crucial towards uncovering players’ agency and unmasking groups’ ideologies.