The Idea of the Anavatapta Lake in India and Its Adoption in East Asia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Anavatapta Lake in the Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions: The Animals in the Four Cardinal Directions and Pictures of Mt. Sumeru

The geography this account illustrates is clearly a fusion of the Buddhist worldview or cosmology and the real topography. The Anavatapta Lake occupies a particularly important place in this geography. The four sides of the lake are flanked by the four animals associated with the four cardinal directions. On each side of the lake, a river flows out of the mouth of the animal. The account also states that the Sītā River is the headstream of China’s Yellow River. I will later expand on this supposed connection between the lake and the Yellow River. These descriptions show that the Anavatapta Lake was a geographical concept that connected the imaginary Buddhist cosmology to reality, and in the course of time, it became so prevalent that it often appeared in various works of literature.In the center of the Jambu continent is the Anavatapta Lake, meaning “No Trouble of Heat”, which is south of the Fragrant Mountain and north of the Great Snow Mountains, with a circuit of eight hundred li. Its banks are adorned with gold, silver, lapis lazuli, and crystal. It is full of golden sand, and its water is as pure and clean as a mirror. A Bodhisattva of the eighth stage, having transformed himself into a Nāga king by the power of his resolute will, makes his abode at the bottom of the lake and supplies water for the Jambu continent. Thus from the mouth of the Silver Ox at the east side of the lake flows out the Ganges, which after going round the lake once enters the Southeast Sea; from the mouth of the Golden Elephant at the south side of the lake flows out the Indus, which after winding round the lake once enters the Southwest Sea; from the mouth of the Lapis Lazuli Horse at the west side of the lake flows the Oxus, which after meandering round the lake once enters the Northwest Sea; and from the mouth of the Crystal Lion at the north side of the lake flows out the Sītā, which after encircling the lake once enters the Northeast Sea, or it is said that it flows by a subterranean course to the Jishi Mountain, where the water reappears as a tributary of the Sītā and becomes the source of the Yellow River in China.2

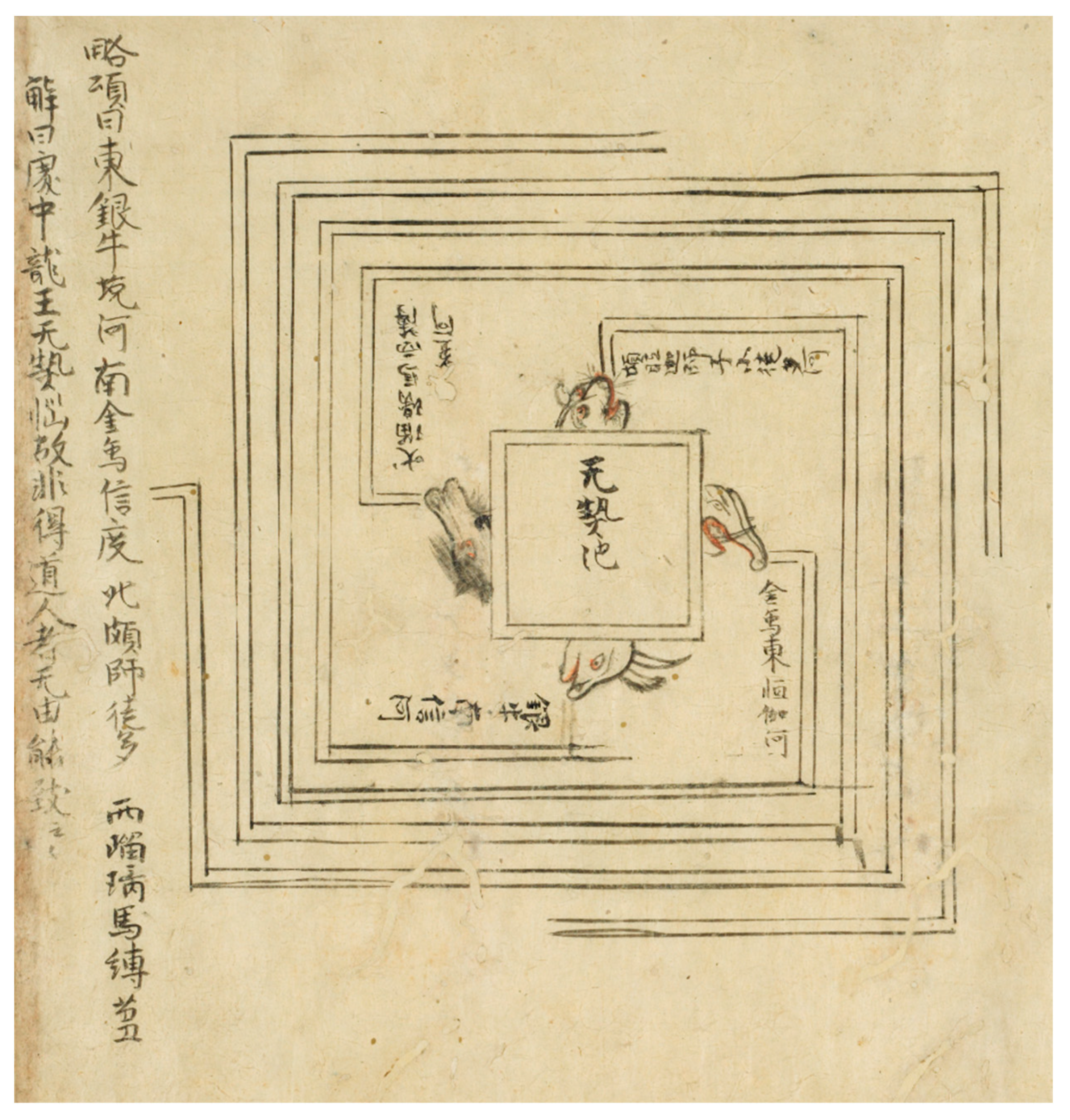

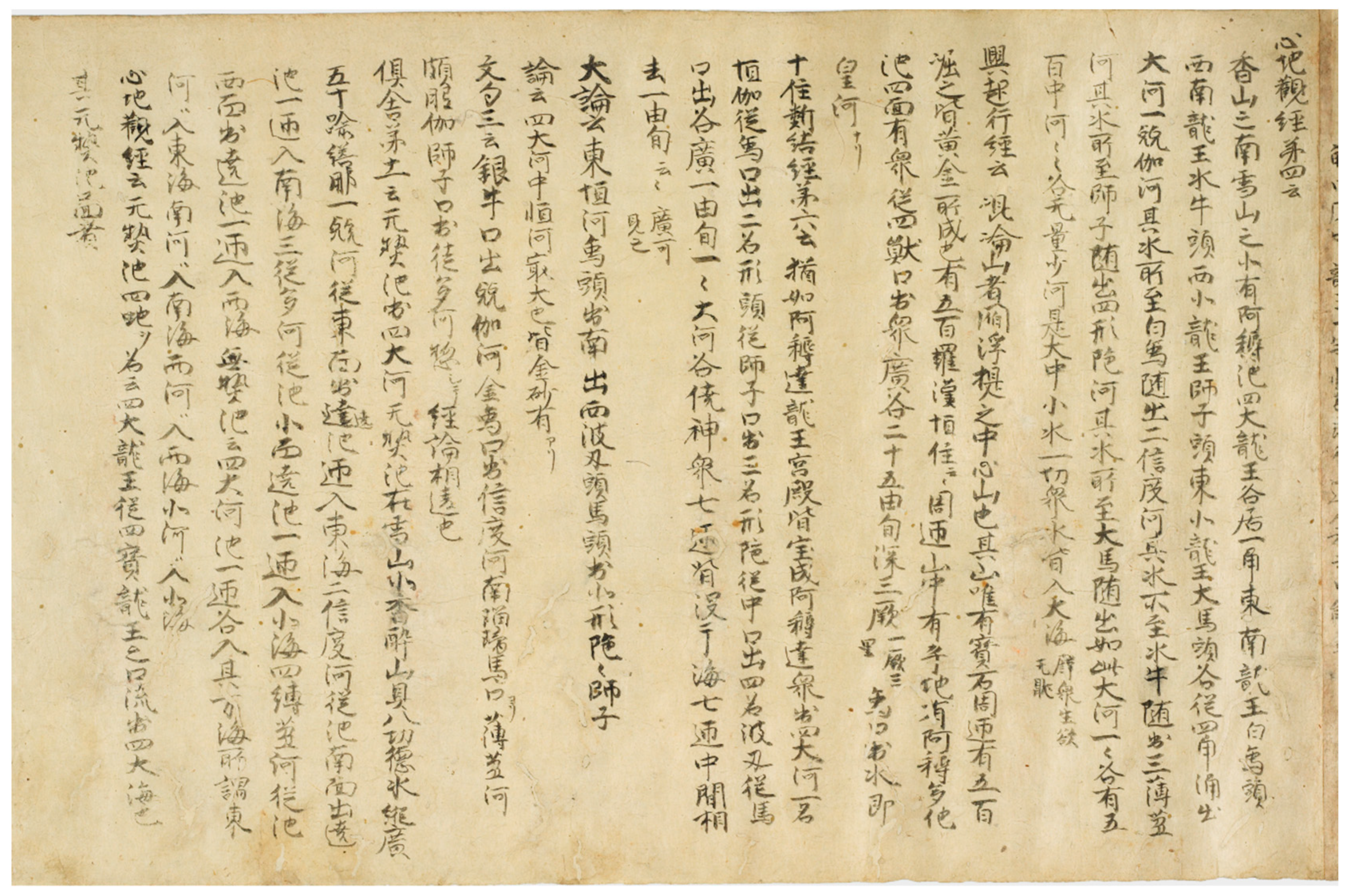

3. The Anavatapta Lake in the Picture of the Buddhist Cosmology in the Harvard Art Museums

This passage places the four animals in the same directions as in Xiyuji. The last part, “no one who has not mastered the dharma can reach it”, is seen in the fascicle 11 of Jushelun 倶舎論 (Jp. Kusharon). Other passages, which also mention the Anavatapta Lake and the four animals, cite various other Buddhist texts: (Dachengbensheng) Xindiguan jing (大乗本生)心地観經 (Jp. Daijō honjō shinjikan gyō), (Foshuo) Xingqixing jing (佛說)興起行經 (Jp. Bussetsukōkigyō kyō),6 Shizhu duanjie jing 十住断結經 (Jp. Jūjū danketsu kyō)7, Dazhidulun 大智度論 (Jp. Daichidoron), Fahua wenju 法華文句 (Jp. Hokke mongu), and Jushelun (Figure 2). They exhibit some variations regarding the geography surrounding the Anavatapta Lake, however.The abridged verse says: the Silver Ox to the east, the Ganges; the Golden Elephant to the south, the Indus; the Crystal Lion to the north, the Sītā; and the Lapis Lazuli Horse to the west, the Oxus. The commentary says: since the Anavatapta Lake is the adobe of a Nāga king, no one who has not mastered the [Buddhist] way can reach it.5

4. Discussions on the Anavatapta Lake in Buddhist Sutras

- (1)

- The Anavatapta Lake is regarded as a sacred site worthy of holy beings:

- (2)

- Water of the Anavatapta Lake is compared to wisdom in dharma:

- (a)

- In the same way water flowing from the Anavatapta Lake nurtures the four-continent world (shitenge 四天下) endlessly, water provided by the bodhisattva’s vows to save all sentient beings nourishes them.20

- (b)

- Good dharma comes from Mahayana, in the same way water comes from the Anavatapta Lake.21

- (c)

- In the same way water from the Anavatapta Lake, where a dragon lives, benefits Buddhist practice, the Four Great Rivers of Dharma flow from bodhisattvas.22

- (d)

- In the same way water from the Anavatapta Lake benefits sentient beings, bodhisattvas benefit sentient beings in the Sea of Wisdom.23

- (3)

- The eradication of afflictions brings about many benefits, in just the same way the ablution in the Anavatapta Lake eradicates sins.24

- (4)

- Breathing disorder will be cured if one visualizes the Anavatapta Lake.25

- (5)

- Shakyamuni’s fearless mind at his defeat of Māra is likened to the calmness of the full water of the Anavatapta Lake and to the immovability of Mt. Sumeru.26

5. Transmission and Reception of the Anavatapta Lake in China

6. Reception and Recreation of the Anavatapta Lake in Japan

- (1)

- The first category includes setsuwa in the early-twelfth-century anthology Konjaku monogatari shū 今昔物語集 (Collection of Tales of Times Now Past) and in the fourteenth-century warrior tale Taiheiki 太平記 (Chronicle of Great Peace). The following episode from Konjaku monogatari shū relates that Nāga’s offspring escaped the danger of the Golden Winged Bird (Garuḍa: konjichō 金翅鳥) only when they were in the Anavatapta Lake:32Long ago in India, various dragon kings lived at the bottom of a great sea. They were always menaced by the attack of the Golden Winged Bird. The dragon kings also had a pond called Munecchi [the Anavatapta Lake] where there was no danger from the bird. The Golden Winged Bird fanned the surface of the great sea with its wings until the water had dried, took the children of the dragon kings and ate them (India Section 3: 9).33

After discussing the origin of Japan’s name (“Nippon”), Jinnō shōtōki expounds the Buddhist cosmology and resituates China and Japan in the India-centric worldview. It emphasizes that China and Japan are remote and small lands on the periphery of Jambudvīpa, where India is situated in the center, and the Anavatapta Lake is placed within this worldview.According to the Buddhist scriptures, there is a mountain called Sumeru, which is surrounded by seven other concentric, golden mountains. Between these golden mountains flows the Sea of Fragrant Waters, and outside them are four great oceans. Within the oceans are four great continents, each of which consists of two lesser parts. The southern continent is called Jambu (or Jambudvīpa, a different form of the same name), and is named after the jambu tree. At the center of the southern continent is a mountain called Anavatapta, and on its summit is a lake. (Anavatapta is also called Bunetsu. It is none other than the mountain known in non-Buddhist sources as K’un-lun.).36

- (2)

- Preaching texts in the collection of the Kanagawa Prefectural Kanazawa-Bunko Museum include a good example of setsuwa that connects Indian myths and Japan through the Anavatapta Lake―namely, the text called Gumonji kuketsu 求聞持口訣.37 According to the text, the Nāga king Zennyo 善如龍王 (Zennyo ryūō) dwells in a pond at the Buddhist temple Murōji on Mt. Murō, and this pond is linked by subterranean streams to the Anavatapta Lake in India, enabling Zennyo to visit the lake frequently. The connection is probably meant to glorify the sanctity of Mt. Murō.38 One noteworthy feature of this episode is that it refers to the dragon in the Anavatapta Lake as the Nāga king Zennyo, whereas Buddhist texts refer to him as a manifestation of various deities such as bodhisattvas of the seventh, eighth, and tenth stages.39 The same is the case with the famous episode contained in Konjaku monogatari shū and Taiheiki in which, during a rainmaking ritual, Kūkai 空海 (774–835)―the founder of Japanese Shingon Buddhism―invited the Nāga king Zennyo from the Anavatapta Lake to a pond of the imperial garden Shinsen’en.40 The Anavatapta Lake was believed to be connected, through subterranean streams, to various sacred water sources in Japan.

- (3)

- The third category is setsuwa in which the Anavatapta Lake appears as a historical precedent against the backdrop of the worldview of the three countries, which saw the entire world as consisting of India, China, and Japan. Our first example in this category is “the Battle at Hiuchi” in Chapter Seven of Heike monogatari 平家物語 (Tale of the Heike):[The Hiuchi stronghold] was a formidable position, surrounded by towering rocks and peaks, with mountains in front and behind; there were also two rivers, the Nōmigawa and the Shindōgawa, in front. At the confluence of the rivers, the defenders had built in an elaborate dam by felling and dragging in mighty trees for branch barricades, so that water lapped at the base of the mountains to the east and the west, just as though the stronghold were facing the lake. “Its surface steeped the southern mountain: blue and vast. Its waves engulfed the westering sun: red and patterned.” On the bottom of the Heatless Lake [Anavatapta Lake], there is silver and golden sand; by the shore at Kunming Lake, there were virtuous-government boats. At this artificial lake near the Hiuchi stronghold, there was a dam with roiling water for the purpose of deception.41

The pagoda, which once stood in a pond, would resemble Mt. Sumeru. Based on the three-country model, the passage stresses the splendor of the pagoda, which it says “excelled any other in the three countries”, by referring to the Anavatapta Lake in India, the Kunming Lake in China, and the Naniwa Bay in Japan reflecting its image. It expands the idea of excellence in the three countries to the famous ponds in the three countries (although the Naniwa Bay is not a pond). The passage takes the loss of the pagoda as a portent to the fall of the Buddhist and Sovereign Laws and the decline of the country.The octagonal nine-story pagoda […] was a pagoda that excelled any other in the three countries (sangoku musō no gantō nari 三国無双ノ雁塔也). When it was first built, its image was reflected onto the surfaces of India’s Anavatapta Lake, China’s Kunming Lake, and Japan’s Naniwa Bay, truly a miraculous event. The fact that an imperial-vow site with such a miraculous power was destroyed by fire in an instant must mean something far more significant than the devastation of this temple alone.43

- (4)

- In the fourth category, the Anavatapta Lake constitutes a metaphor. An example is in the writings of the prominent monk Nichiren 日蓮 (1222–1282). While in exile on Sado Island, Nichiren wrote letters to his disciples and lay followers who were shaken by the persecution of Nichiren. Below is a passage from one of the letters:An arrogant person will always be overcome with fear when meeting a strong enemy, as was the haughty asura who shrank in size and hid himself in a lotus blossom in Heat-Free Lake when reproached by Shakra.44

In China, F’ei-kung fought with Hsiang-yü (Kō-u) for eight years. In Japan, Yoritomo fought with Munemori for seven years. Asuras fought with Śakra. Garuḍas fought with dragons at the Anavatapta Pond. But these fights were not so severe [as the controversies between the advocates of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sutra and the slanders of it].47

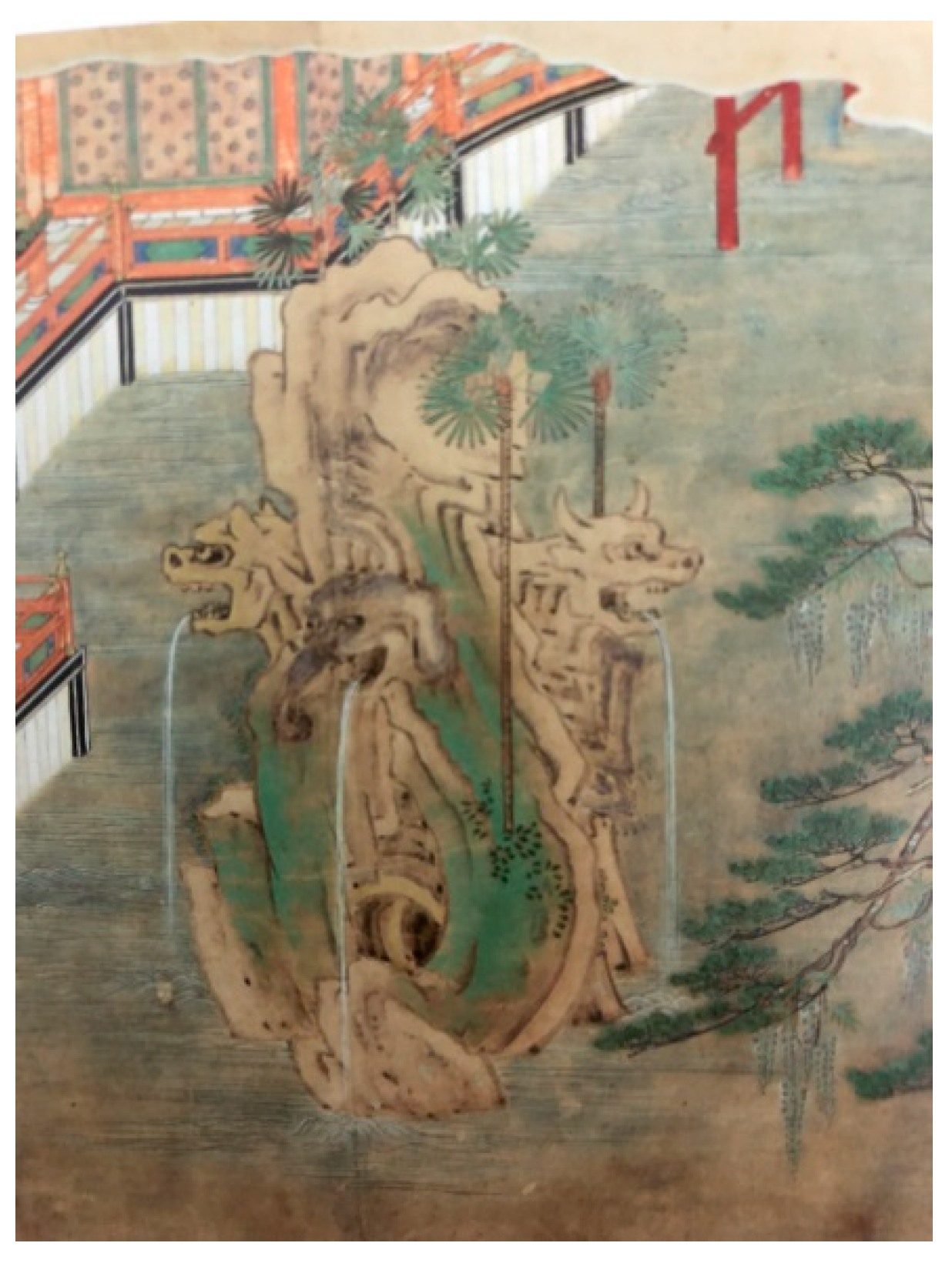

7. The Anavatapta Lake in the Garden in the Illustrated Biography of Xuanzang

Though this passage does not mention the Anavatapta Lake, it refers to a pond where a dragon lived. Perhaps because of the dragon inhabiting in the pond, the Illustrated Life of Xuanzang associates the pond with the Anavatapta Lake and portrays the pond with a fountain of the four animals in the four cardinal directions.Nālandā Monastery means the monastery of Insatiability in Almsgiving. It was said by old tradition that to the south of the monastery there had been a pond in a mango grove in which lived a dragon named Nālanda. As the monastery was built beside the pond, it was named so. It was also said that when the Tathāgata was practicing the Bodhisattva path in one of his former lives, he was a great king and founded his capital at this place. As he had pity on the poor and the lonely, he often gave alms to them; and in memory of his beneficence the people called the place Insatiability in Almsgiving.52

8. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T | SAT Daizōkyō Text Database (SAT大正新脩大蔵経テキストデータベース). 2018 version. Tokyo: University of Tokyo. http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/. |

References

Primary Sources

(Foshuo) Xingqixing jing (佛說)興起行經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 15 November 2018).Da Piluzhena chengfo jing shu 大毘盧遮那成佛經疏. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 20 April 2019).Daban niepan jing 大般涅槃經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 20 April 2019).Dabaoji jing 大宝積經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 20 April 2019).Dafang guangfo huayan jing 大方広佛華厳經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 3 May 2019).Dasheng baoyun jing 大乘宝雲經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 3 December 2018).Dazhidulun 大智度論. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Foshuo chang ahan jing 佛說長阿含經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Foshuo huashou jing 佛說華手經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Foshuo zhufa yongwang jing 佛說諸法勇王經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 7 January 2018).Fozutongji 佛祖統紀. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 8 November 2018).Heike monogatari 平家物語. Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshū 新編日本古典文学全集 45–46. Tokyo: Shōgakukan, 1994.Konjaku monogatari shū 今昔物語集. Vols. 1–3. Shin Nihon koten bungaku taikei 新日本古典文学大系 33–35. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1993–1997.Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮華經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 8 November 2018).Nihon shoki 日本書紀. Nihon koten bungaku taikei 日本古典文学大系 68. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1965.Ruyi baozhu zhuanlun mimi xianshen chengfo jinlun zhouwang jing 如意宝珠転輪秘密現身成佛金輪呪王經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Sanpō-e, Chūkōsen 三宝絵, 注好選. Shin nihon koten bungaku taikei 新日本古典文学大系 31. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1997.Shengman baoku 勝鬘宝窟. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 1 December 2018).Shisonglu 十誦律. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Shizhu jing 十住經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Taiheiki 太平記, vols. 1–3. Nihon koten bungaku taikei 日本古典文学大系 34. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1960.Xindiguan jing 心地觀經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Zhichan bingmi yaozhu 治禅病祕要法. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Zuisheng wen pusa shizhu chugou duanjie jing 最勝問菩薩十住除垢断結經. T. Available online: http://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT2018/master30.php (accessed on 5 November 2018).Secondary Sources

- Araki, Hiroshi 荒木浩. 2015. Shohyō: Koten ronkō–Nihon to iu shiza 書評:古典論考―日本という視座. Kokubungaku kenkyū 国文学研究 176: 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiko Kurata Dykstra, trans. 1998, The Konjaku Tales Japanese Section (I): From a Medieval Japanese Collection. Osaka: Kansai Gaidai University Publication.

- Yoshiko Dykstra, trans. 2014, Buddhist Tales of India, China, and Japan: India Section. Honolulu: Kanji Press.

- Gao, Yang 高陽. 2010. Shumisen to tenjō sekai: Haabaado daigaku shozō Nihon shumi shoten zu to Chūgoku no Hokkai anryū zu o megutte 須弥山と天上世界―ハーバード大学所蔵『日本須弥諸天図』と中国の『法界安立図』をめぐって. In Kanbun bunka ken no setsuwa sekai 漢文文化圏の説話世界. Edited by Komine Kazuaki 小峯和明. Tokyo: Chikurinsha, pp. 259–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Yang 高陽. 2012. Higashi Ajia no shumisen zu: Tonkō-bon to Haabaado-bon o chūshin ni 東アジアの須弥山図―敦煌本とハーバード本を中心に. In Higashi Ajia no Konjaku monogatari shū: Honyaku, hensei, yogen 東アジアの今昔物語集―翻訳・変成・予言. Edited by Komine Kazuaki 小峯和明. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, pp. 263–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Yang 高陽. 2017. Tenjiku shinwa no ikusa o megutte–Taishakuten to ashura no tatakai o chūshinni 天竺神話のいくさをめぐって―帝釈天と阿修羅の戦いを中心に. In Nihon bungaku no tenbō o hiraku 日本文学の展望を拓く, vol. 3. Shūkyō bungei no gensetsu to kankyō 宗教文芸の言説と環境. Edited by Komine Kazuaki 小峯和明 and Hara Katsuaki 原克昭. Tokyo: Kasama Shoin, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gasho Translation Committee, trans. 1999. The Writings of Nichiren Daishōnin . Writings of Nichiren Daishōnin. Available online: https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/wnd-1/Content/32 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Komatsu, Shigemi 小松茂美, ed. 1975. Ban dainagon ekotoba 伴大納言絵詞. Nihon emaki taisei 日本絵巻大成 2. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha. [Google Scholar]

- Komine, Kazuaki 小峯和明. 2011. Shumisen sekai no gensetsu to zuzō o meguru 須弥山世界の言説と図像をめぐる. In Ajia shinjidai no minami Ajia ni okeru nihon zō: Indo, SAARC shokoku ni okeru Nihon kenkyū no genjō to hitsuyōsei アジア新時代の南アジアにおける日本像 インド・SAARC諸国における日本研究の現状と必要性. Edited by International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies, pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Komine, Kazuaki 小峯和明, and Fujisawa Shūhei 藤沢周平, eds. 1991. Konjaku monogatari shū, Uji shūi monogatari. 今昔物語集・宇治遺物語. Shinchō koten bungaku arubamu 新潮古典文学アルバム. Tokyo: Shinchōsha, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Rongxi Li, trans. 1995, A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty. Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

- Rongxi Li, trans. 1996, The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

- Lü, Jianfu 呂建福. 2005. Fojiao shijieguan dui Zhonguo gudai dili zhongxin guanniande yingxiang 仏教世界観対中国古代地理中心観念的影響. Shanxi shifan daxue xuebao, Zhexue shehui, Kexueban 陜西師範大学学報・哲学社会・科学 4: 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Jianfu. 2015. The Influence of Buddhist Cosmology on the Idea of the Geographical Center in Pre-Modern China. In Buddhism. Edited by Yulie Lou. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 255–87. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, Masaaki 前田雅之. 2014. Koten ronkō–Nihon to iu shiza 古典論考―日本という視座. Tokyo: Shintensha. [Google Scholar]

- Helen Craig McCullough, trans. 1988, The Tale of the Heike. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Helen Craig McCullough, trans. 2004, The Taiheiki: A Chronicle of Medieval Japan. Rutland: Tuttle.

- Murai, Shōsuke 村井章介. 2014. Nihon no jigazō 日本の自画像. In Iwanami koza nihon no shisō 岩波講座日本の思想. vol. 3: Uchi to soto: Taigaikan to jikozō no keisei 内と外・対外観と自己像の形成. Edited by Karube Tadashi 苅部直. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, pp. 45–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sencho Murano, trans. 2000, Kaimokushō or Liberation from Blindness. Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

- Nara Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan 奈良国立博物館, ed. 2011. Tenjiku e: Sanzō hōshi 3 man kiro no tabi 天竺へ 三蔵法師3万キロの旅. Exhibition catalogue. Nara: Nara Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Shūei 高橋秀栄. 1994. Heian Kamakura bukkyō yō bunshū, ge 平安鎌倉仏教要文集 下. Komazawa daigaku bukkyō gakubu kenkyū kiyō 駒澤大学仏教学部研究紀要 52: 257–85. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Varley, trans. 1980, A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns: Jinnō Shōtōki of Kitabatake Chikafusa. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Wang, Zhongmin 王重民, Qingshu Wang 王庆菽, Xiang Da 向达, Yiliang Zhou 周一良, Gong Qi 启功, and Yigong Zeng 曾毅公, eds. 1984. Dunhuang bianwen ji 敦煌変文集. Beijing: Renmin Wenxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yakushiji 薬師寺. 2015. Genjō sanzō to Yakushiji 玄奘三蔵と薬師寺. Nara: Hossōshū Daihonzan Yakushiji. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The preface also covers the first-hand observation of the sites Xuanzang visited and the second-hand information he collected during his journey to Central Asia and India, and describes these places in relation to the Buddhist worldview. For previous scholarship on Mt. Sumeru, see (Komine 2011, pp. 45–55; Gao 2010, pp. 259–82; Gao 2012, pp. 263–84). |

| 2 | (Li 1996, p. 18). For the Fragrant Mountain (kōzan 香山), see (Maeda 2014, pp. 237–80; Araki 2015, p. 58). |

| 3 | The Harvard scroll was first introduced by Komine in his co-edited book, (Komine and Fujisawa 1991, pp. 2–25); also see (Komine 2011, pp. 49–52) in which Komine discusses the scroll in detail. Gao further investigated the scroll in comparison with a three-volume Ming publication entitled Fajie anli tu法界安立図 (Dharma Realm Diagrams; printed in 1584) and Sangai kuji no zu 三界九地之図 (Depiction of Three Realms and Nine Levels; ninth or tenth century) that was discovered in Dunhuang. (Gao 2010, pp. 259–82; Gao 2012, pp. 263–84). For the discussion of Gyōki map in the Harvard scroll, see (Murai 2014, pp. 45–83). |

| 4 | For instance, the earliest extant Map of India (dated to 1364) in the collection of Hōryūji and the Edo-period map titled Nansenbushū bankoku shōkanozu (1710) show a similar map. For these maps, see (Yakushiji 2015, pp. 37–39). |

| 5 | It is not clear what is the source of this abridged verse and the commentary. It is likely, however, that they are derived from a commentary of the Treasury of Abhidharma. |

| 6 | (Foshuo) Xingqixing jing (佛說)興起行經, T197, vol. 4, p. 163, c, l3.18. |

| 7 | Shizhu duanjie jing is also known as Zuisheng wen pusa shizhu chugou duanjie jing 最勝問菩薩十住除垢断結經, T309, vol. 10, p. 1011, a, 8.20. |

| 8 | An explanatory note to the final passage reads “is comparable to not to disgust against sentient being’s desire.” The description of the Anavatapta Lake in Xindiguan jing can be found in T159, vol. 3, p. 307, c, l.5. |

| 9 | There is a variation between the excerpt and the original text: while the inscription in the Harvard scroll says that the Sītā River measures three li, the original text says it measures seven li. See (Foshuo) Xingqixing jing, T197, vol. 4, p. 163, c, l3.18. |

| 10 | Dazhidulun, T1509, vol. 25, p. 114, a, 15.25. |

| 11 | Dafang guangfo huayan jing 大方広佛華厳經, T279, vol. 10, p. 208, c, l2.16. |

| 12 | Fozutongji 佛祖統紀, fascicle 32, T2035, vol. 49, p. 314, a, 2.8. |

| 13 | Da Piluzhena chengfo jing shu 大毘盧遮那成佛經疏, fascicle 15, T1796, vol. 39, p. 734, a, 22.25. |

| 14 | For instance, see the preface to Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮華經, T1718, vol. 34, p. 24, c, l8.20. |

| 15 | Foshuo chang ahan jing 佛說長阿含經, T1, vol. 1, p. 116, c, 05.18. |

| 16 | For instance, see Shengman baoku 勝鬘宝窟, fascicle middle, T1744, vol. 37, p. 43, a, 27.29. |

| 17 | Shisonglu 十誦律, fascicle 2, T1435, vol. 23, p. 346, a, 9.28. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | Ruyi baozhu zhuanlun mimi xianshen chengfo jinlun zhouwang jing 如意宝珠転輪秘密現身成佛金輪呪王經, fascicle 1, T961, vol. 19, p. 331, c, 6.8. |

| 20 | Dafang guangfo huayan jing 大方広佛華厳經, fascicle 27, T279, vol. 10, p. 222, b, l6.29; Shizhu jing 十住經, T286, vol. 10, p. 531, b, 26.28. |

| 21 | Dabaoji jing 大宝積經, fascicle 119, T310, vol. 11, p. 575, a, 8.10. |

| 22 | Foshuo huashou jing 佛說華手經, fascicle 7, T657, vol. 16, p. 182, c, 29.a05. |

| 23 | Foshuo zhufa yongwang jing 佛說諸法勇王經, T822, vol. 17, p. 848, b, 22.28. |

| 24 | Daban niepan jing 大般涅槃經, fascicle 23, T375, vol. 12, p. 755, c, 9.12. |

| 25 | Zhichan bingmi yaozhu 治禅病祕要法, fascicle 1, T620, vol. 15, p. 335, b, 3.18. |

| 26 | Dasheng baoyun jing 大乘宝雲經, fascicle 1, T659, vol. 16, p. 241, c, l0.11. |

| 27 | (Lü 2005, pp. 75–82; also see Lü 2015, p. 267). |

| 28 | (Lü 2005, p. 77; 2015, p. 267). As we have seen, a similar interpretation is also stated in the Harvard scroll. |

| 29 | In the Qing period (1644–1912), firsthand surveys of the river systems of the Yellow River led to the identification of Mt. Anavatapta (or Mt. Kunlun) with Mt. Kailash 岡底斯山, an actual mountain in Tibet. (Lü 2005, p. 77; 2015, pp. 268–70). |

| 30 | |

| 31 | |

| 32 | The same episode is compiled in a collection of didactic tales Chūkōsen 注好選 in the twelfth century. Sanpō-e, Chūkōsen 1997, p. 367. |

| 33 | (Dykstra 2014, p. 149); also see Konjaku monogatari shū 1999, p. 221. |

| 34 | In Kitano tsuya monogatari, the Buddhist monk Raii of Hino visits Kitano Shrine, and listens to a dialogue between a hermit, a courtier, and a Buddhist monk all night long. These dialogists narrate Indian, Chinese, and Japanese tales, with which they castigate the sovereign’s rulership in Japan in the middle of the civil war between the Northern and Southern Courts. |

| 35 | Konjaku monogatari shū 1999, p. 170; see also (Dykstra 2014, pp. 115–20). |

| 36 | |

| 37 | Originally the collection was housed in the archives in the complex of the Buddhist temple Shōmyōji in Yokohama. For Gumonji kuketsu, see (Takahashi 1994, p. 275). |

| 38 | Gumonji kuketsu goes on to say that the monk Huiguo 恵果 (746–806), who transmitted esoteric Buddhist tradition to Kūkai at Qinglong Monastery in Chang’an in 805, has moved to Mt. Murō, and that whenever a Shingon master visits Mt. Murō, Huiguo welcomes him, whereas if an inexperienced practitioner visits there, he will be slaughtered by poisonous snakes and other creatures. (Takahashi 1994, p. 275). |

| 39 | Although the Dragon King Zennyo appears in Baoxidi chengfo tuoluo ni jing 宝悉地成佛陀羅尼經 translated by Amoghavajra (705–774), it appears more frequently in Japanese sources more frequently. We can assume that the name Zennyo was more familiar to Japanese people through a wide reception of the setsuwa literature. |

| 40 | See “Matter of the Garden of Divine Waters”, in (McCullough 2004, p. 374); Taiheiki 1960, pp. 420–24. Also see Konjaku monogatari shū 1993, p. 359; “How Master Kōbō Practiced the Cult of Shōukyō and Caused a Downpour”, in (Dykstra 1998, pp. 248–49). |

| 41 | (McCullough 1988, p. 227); also see Heike monogatari 1994, pp. 25–28. |

| 42 | The image of the Kunming Lake seems to have permeated among Japanese people. For instance, in the Illustrated Scroll of the Story of the Courtier Ban (Ban dainagon ekotoba), the lake is depicted on a free-standing panel behind a courtier in formal attire in the scene where the chancellor Fujiwara no Yoshifusa (804–872) makes a direct appeal to Emperor Seiwa (850–881; r. 858–876) that the minister of the left, Minamoto no Makoto, is innocent of having set fire to the Ōten-mon gate. Ban dainagon ekotoba (Komatsu 1975, pp. 28–29). |

| 43 | Taiheiki 1960, pp. 144–146. |

| 44 | |

| 45 | |

| 46 | |

| 47 | Saddharmapuṇḍarīka-sutra is a Sanskrit name of the Lotus Sutra. Translation is from (Murano 2000, p. 81). |

| 48 | For the Illustrated Biography of Xuanzang, see (Nara Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan 2011, p. 91). |

| 49 | Nihon shoki 1965, pp. 198, 330, 336, 343. |

| 50 | It is now preserved in the Asuka Historical Museum, along with a reconstructed model. |

| 51 | |

| 52 | (Li 1995, p. 93). The scroll text that accompanies the illustration in the Illustrated Life of Xuanzang is almost identical. In addition, a similar account is recorded in “the Country of Magadha” of the ninth fascicle of Xuanzang’s Record of the Western Regions. (Li 1996, p. 281). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y. The Idea of the Anavatapta Lake in India and Its Adoption in East Asia. Religions 2020, 11, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030134

Gao Y. The Idea of the Anavatapta Lake in India and Its Adoption in East Asia. Religions. 2020; 11(3):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030134

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yang. 2020. "The Idea of the Anavatapta Lake in India and Its Adoption in East Asia" Religions 11, no. 3: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030134

APA StyleGao, Y. (2020). The Idea of the Anavatapta Lake in India and Its Adoption in East Asia. Religions, 11(3), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030134