The Relevance of the Centrality and Content of Religiosity for Explaining Islamophobia in Switzerland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. State of Research

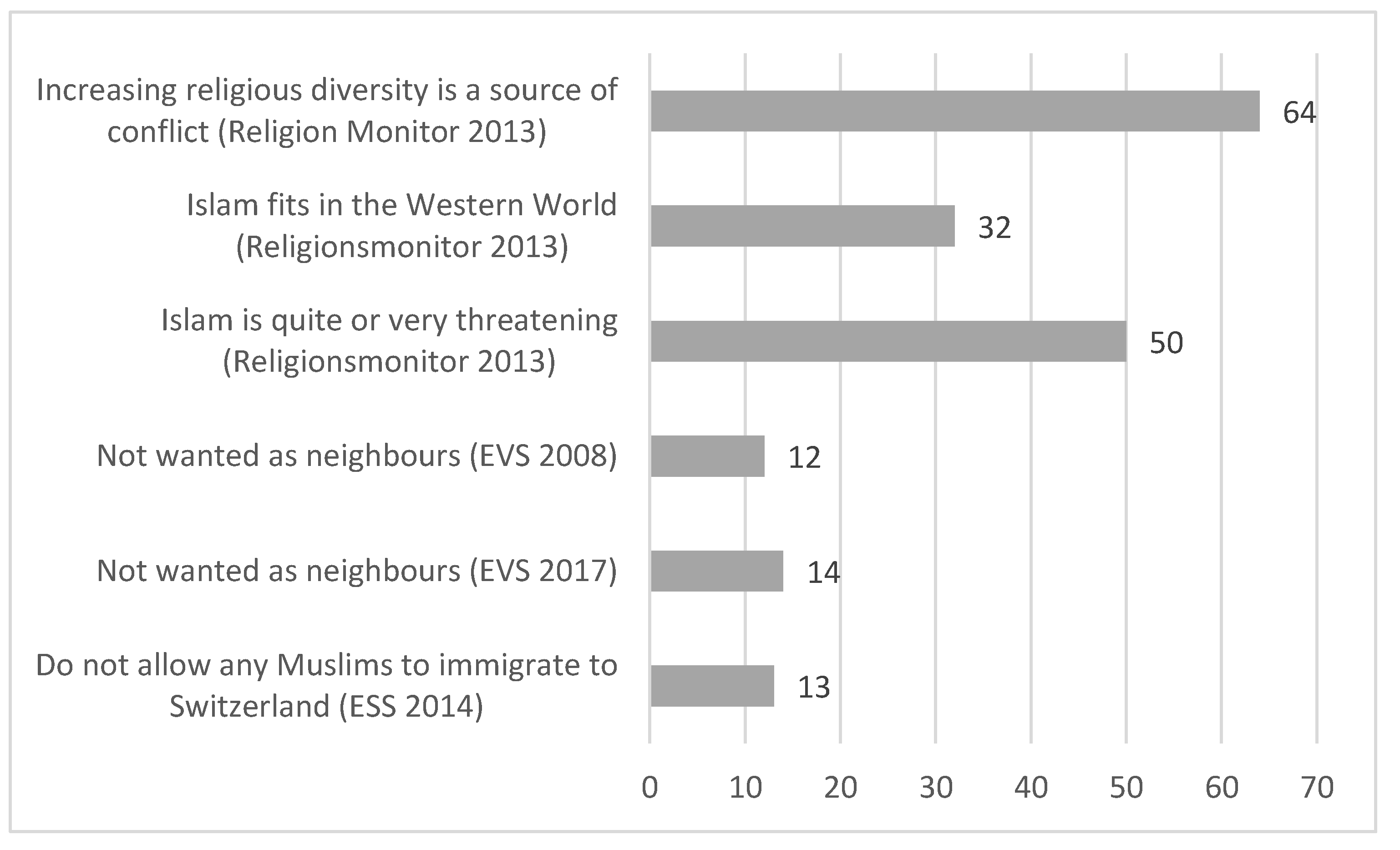

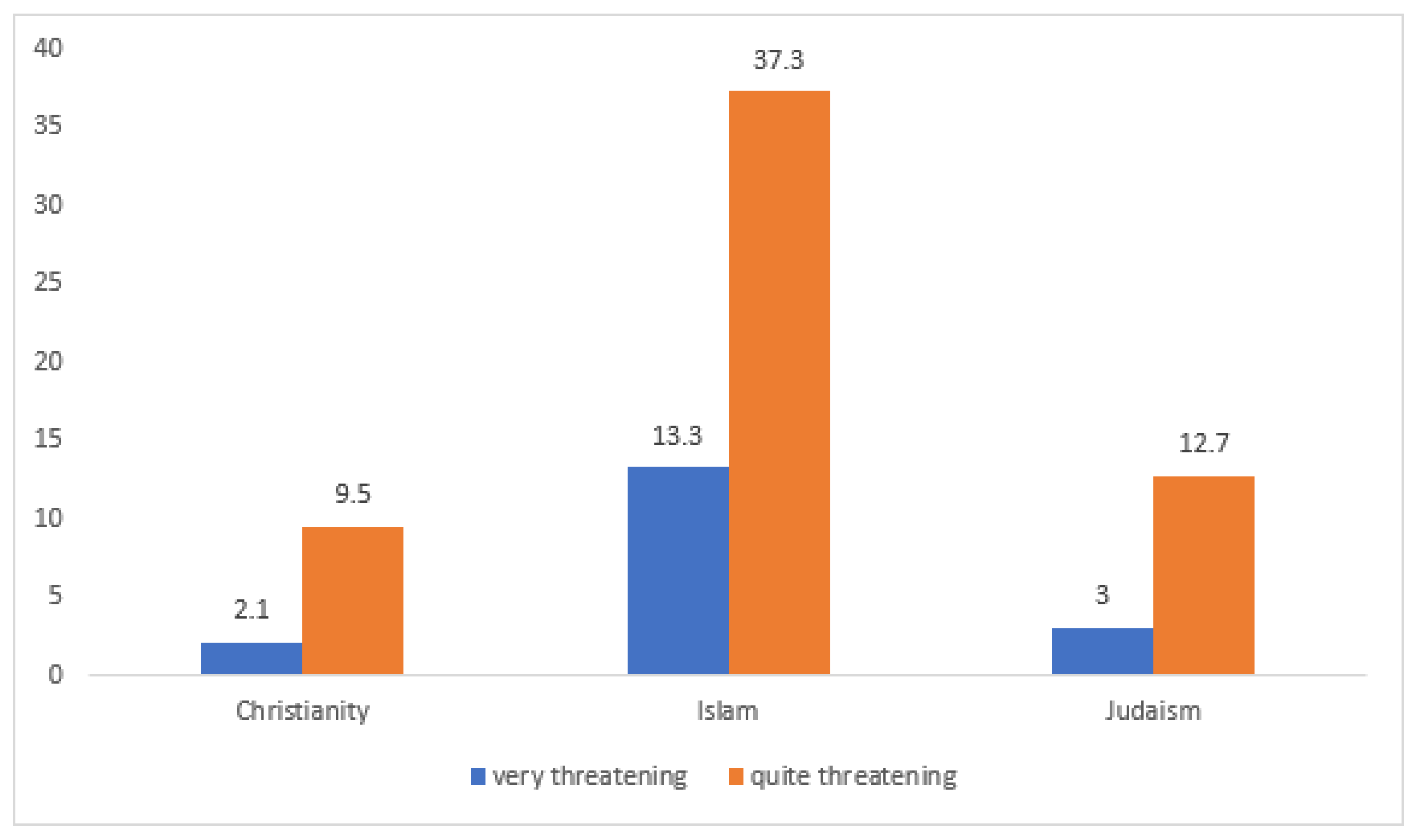

1.1.1. Islamophobia in Switzerland: A Few Figures and the State of Research

1.1.2. The Impact of Religiosity on Prejudices: The State of Research

1.1.3. The Impact of Religiosity on Prejudices other than Islamophobia: The State of Research

1.2. Religiosity and Prejudices in a Model of Religiosity

“Religious fundamentalism is a religious attitude that is characterized by a syndrome of certain characteristics. At its core, an exclusivist understanding of one’s own religion and a strictly intratextual search for absolute religious truth come into effect. Religious exclusivity and absolutism do not in themselves constitute a fundamentalist attitude. Additional characteristics come into play. Dualistic constructions which make a clear distinction between an area of good and salvation on the one hand and an area of evil and misery on the other are essential. After all, one should only speak of a fundamentalist-religious attitude if there is a strong social cohesion and a high level of commitment to one’s own religious group” (Huber in print).

1.3. Political and Social-Psychological Dimension of Prejudices: “the Usual Suspects”

- (1)

- Age (adults are more privileged than children);

- (2)

- Gender (men usually have more power then women);

- (3)

- An arbitrary system (culturally defined group-based hierarchies).

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Method and Data

2.2. Variables

- Political orientation was measured on a scale from 0 (left) to 100 (right). Left-wing individuals (0 to 34) felt less threatened than those in the middle (35 to 65) and those on the right (66 to 100) (35% versus 63% versus 84%);

- The full RWA scale is created from the mean of six variables. People with a high mean (≥ 1.5) felt more threatened by Islam than those with a low mean (< 1.5) (75% versus 44%);

- Social Dominance Orientation is created from the mean of seven variables. People with a high level (≥ 50) felt more threatened than those with a low level (< 50) (73% versus 48%);

- Religious Fundamentalism is created from the mean of six variables. People with a high mean (≥ 1.5) felt more threatened than those with a low mean (< 1.5) (55% versus 43%);1

- Secular threat is created from the mean of two variables. People with a high mean (≥ 2.5) felt more threatened than those with a low mean (< 2.5) (78% versus 45%);

- The centrality of religiosity scale (CRSi-7) is created from seven variables. People who were not religious (1 to 2) felt more threatened by Islam than those who were religious (2.2 to 3.8) and than those who were very religious (4 to 5) (59% versus 48% versus 51%);

- Age as a metric variable. There was no linear direction between age groups (below 20: 50% felt threatened; 20 to 34: 53%; 35 to 49: 51%; 50 to 64: 51%; 65 and above: 47%);

- Gender: male 0/female 1: Males felt more threatened by Islam than females (57% versus 44%);

- Education (highest level of educational achievement): secondary school (58% felt threatened); middle school and grammar school (39% felt threatened); vocational school (59% felt threatened); university or college degree (48% felt threatened).

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ademović-Omerčić, Nermina. 2018. Islamophobia in Switzerland. National Report 2017. In European Islamophobia Report 2017. Edited by Enes Bayrakli and Farid Hafez. Istanbul: SETA, pp. 647–70. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, and R. Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper und Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, Gordon, and John M. Ross. 1967. Personal Religious Orientation and Prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, Gabriel A., R. Scott Appleby, and Emmanuel Sivan. 2003. Strong Religion: The Rise of Fundamentalisms Around the World. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer, Robert A. 1981. Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: Univ. of Manitoba Pr. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer, Bob, and Bruce Hunsberger. 1992. Authoritarianism, Religious Fundamentalism, Quest, and Prejudice. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, Bob, and Bruce Hunsberger. 2004. A Revised Religious Fundamentalism Scale: The Short and Sweet of It. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 14: 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, Stephen J. Naifeh, and Suzanne Pate. 1978. Social Desirability, Religious Orientation, and Racial Prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behloul, Samuel-Martin. 2009. Discours total! Le debat sur l’Islam en Suisse et le positionnement del’Islam comme religion publique. In Musulmans d’aujourd’hui: Identités Plurielles en Suisse. Edited by Nadia Bagdadi and Mallory Schneuwly Purdie. Religions et Modernités 4. Genève: Labor et Fides, pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein, Constanze, Frank Asbrock, Mathias Kauff, and Peter Schmidt. 2014. Kurzskala Autoritarismus (KSA-3). GESIS-Working Papers 35. Available online: https://www.gesis.org/fileadmin/kurzskalen/working_papers/KSA3_WorkingPapers_2014-35.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Berger, Roger, and Joël Berger. 2019. Islamophobia or Threat to Secularization? Lost Letter Experiments on the Discrimination Against Muslims in an Urban Area of Switzerland. Swiss Journal of Sociology 45: 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS). 2019. Die Bevölkerung der Schweiz 2018. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/asset/de/348-1800 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Cheng, Jennifer E. 2015. Islamophobia, Muslimophobia or racism? Parliamentary discourses on Islam and Muslims in debates on the minaret ban in Switzerland. Discourse & Society 26: 562–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrs, J. Christopher, and Frank Asbrock. 2009. Right-Wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation and Prejudice Against Threatening and Competitive Ethnic Groups. European Journal of Social Psychology 39: 270–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, Oliver, and Elmar Brähler. 2016. Autoritäre Dynamiken: Ergebnisse der bisherigen »Mitte«-Studien und Fragestellung. In Die enthemmte Mitte: Autoritäre und rechtsextreme Einstellung in Deutschland. Edited by Oliver Decker, Johannes Kiess and Elmar Brähler. Originalausgabe. Forschung Psychosozial. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, Oliver, and Elmar Brähler, eds. 2018. Flucht ins Autoritäre: Rechtsextreme Dynamiken in der Mitte der Gesellschaft. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, Oliver, Marliese Weißmann, Johannes Kiess, and Elmar Brähler. 2010. Die Mitte in der Krise: Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2010. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Forum Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, Oliver, Johannes Kiess, and Elmar Brähler, eds. 2012. Die Mitte im Umbruch: Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2012. Bonn: Dietz. [Google Scholar]

- Decker, Oliver, Johannes Kiess, and Elmar Brähler, eds. 2014. Die stabilisierte Mitte: Rechtsextreme Einstellung in Deutschland 2014. Leipzig: Available online: http://www.qucosa.de/fileadmin/data/qucosa/documents/14490/Mitte_Leipzig_Internet.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Decker, Oliver, Johannes Kiess, and Elmar Brähler, eds. 2016. Die Enthemmte Mitte—Rechtsextreme und autoritäre Einstellung 2016. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Doebler, Stefanie. 2014. Relationships Between Religion and Intolerance Towards Muslims and Immigrants in Europe: A Multilevel Analysis. Review of Religious Research 56: 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doktór, Tadeusz. 2002. Factors Influencing Hostility Towards Controversial Religious Groups. Social Compass 49: 553–62. Available online: http://scp.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/49/4/553 (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Dru, Vincent. 2007. Authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice: Effects of various self-categorization conditions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43: 877–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, Rob, Ruben Konig, and Peer Scheepers. 1995. Orthodox Religious Beliefs and Anti-Semitism: A Replication of Glock and Stark in the Netherlands. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34: 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ekici, Tufan, and Deniz Yucel. 2015. What Determines Religious and Racial Prejudice in Europe? The Effects of Religiosity and Trust. Social Indicators Research 122: 105–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Jonathan. 2008. A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, Erich. 1941. Escape from Freedom. New York: Farrar and Rinehart. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the Study of Religious Commitment. Religious Education 57: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, Gregory M. 1987. Religious Orientation and Prejudice: A Comparison of Racial and Sexual Attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 13: 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, Andrew. 2015. Key Concepts in Politics and International Relations, 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Ralph W., Peter C. Hill, and William P. Williamson. 2005. The Psychology of Religious Fundamentalism. New York: Guilford Press. Available online: http://site.ebrary.com/lib/alltitles/docDetail.action?docID=10210593 (accessed on 25 December 2019).

- Huber, Stefan. 2003. Zentralität und Inhalt: Ein Neues Multidimensionales Messmodell der Religiosität [Centrality and Content: A New Multidimensional Measurement Model of Religiosity]. Opladen: Leske + Budrich. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2007. Are religious beliefs relevant in daily life? In Religion Inside and Outside Traditional Institutions. Edited by Heinz Streib. Empirical studies in theology. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2008. Kerndimensionen, Zentralität und Inhalt. Ein interdisziplinäres Modell der Religiosität. Journal für Psychologie 16. Available online: https://www.journal-fuer-psychologie.de/index.php/jfp/article/view/202/105 (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- Huber, Stefan. 2009. Religion Monitor 2008: Structuring Principles, Operational Constructs, Interpretive Strategies.Bertelsmann Stiftung. In What the World Believes: Analysis and Commentary on the Religion Monitor. Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2020. Hochreligiös gleich fundamentalistisch? Eine Einordnung. in print. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Volkhard Krech. 2009. The Religious Field Between Globalization and Regionalization: The Religious Field Between Globalization and Regionalization: Comparative Perspectives. Comparative Perspectives. In What the World Believes: Analysis and Commentary on the Religion Monitor. Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, pp. 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Matthias Richard. 2010. The Inventory of emotions towards God (EtG). Psychological Valences and Theological Issues. Review of Religious Research 52: 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, Mathias Allemand, and Odilo W. Huber. 2011. Forgiveness by God and human forgivingness: The Centrality of the Religiosity Makes the Difference. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 33: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Alexander Yendell. 2019. Does religiosity matter?: Explaining right-wing extremist attitudes and the vote for the Alternative for Germany (AfD). RASCEE 12: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelen, Ted G., and Clyde Wilcox. 1991. Religious Dogmatism Among White Christians: Causes and Effects. Review of Religious Research 33: 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Jong H. 2012. Islamophobia? Religion, Contact with Muslims, and the Respect for Islam. Review of Religious Research 54: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornyeyeva, Lena, and Klaus Boehnke. 2013. The Role of Self-Acceptance in Authoritarian Personality Formation: Reintroducing a Psychodynamic Perspective into Authoritarianism Research. Psychoanalytic Psychology 30: 232–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, Beate, and Andreas Zick. 2006. Riskanter Glaube. Religiosität und Abwertung. In Deutsche Zustände. Folge 4. Edited by Wilhelm Heitmeyer. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, pp. 179–88. [Google Scholar]

- Küpper, Beate, and Andreas Zick. 2010. Religion and Prejudice in Europe. New Empirical Findings. London: Alliance Publishing Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Knud. S., and Gary Schwendiman. 1969. Authoritarianism, Self Esteem and Insecurity. Psychological reports 25: 229–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laythe, Brian, Deborah G. Finkel, Robert G. Bringle, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2002. Religious Fundamentalism as a Predictor of Prejudice: A Two-Component Model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 623–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, Anaïd, and Jörg Stolz. 2014. Use of Islam in the Definition of Foreign Otherness in Switzerland: A Comparative Analysis of Media Discourses Between 1970–2004. Islamophobia Studies Journal 2: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, Stephen M. 2010. Religious diversity in a “Christian nation”: The effects of theological exclusivity and interreligious contact on the acceptance of religious diversity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 231–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Thomas. 1995. Fundamentalismus: Der Kampf gegen Aufklärung und Moderne. 1. Aufl. Humanismus aktuell. Dortmund: Humanitas-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Thomas. 2011. Was ist Fundamentalismus? Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Benjamin J., Todd K. Hartman, and Charles S. Taber. 2014. Social Dominance and the Cultural Politics of Immigration. Political Psychology 35: 165–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickel, Gert, and Alexander Yendell. 2018. Religion als konfliktärer Faktor Im Zusammenhang Mit Rechtsextremismus, Muslimfeindschaft und AfD-Wahl. In Flucht Ins Autoritäre: Rechtsextreme Dynamiken in der Mitte der Gesellschaft. Edited by Oliver Decker and Elmar Brähler. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag, pp. 217–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, Detlef. 2014. Das Verhältnis zu den Muslimen. In Grenzen der Toleranz: Wahrnehmung und Akzeptanz religiöser Vielfalt in Europa. Edited by Detlef Pollack, Olaf Müller, Gergely Rosta, Nils Friedrichs and Alexander Yendell. Veröffentlichungen der Sektion Religionssoziologie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, Detlef, Olaf Müller, Gergely Rosta, Nils Friedrichs, and Alexander Yendell. 2014. Grenzen der Toleranz: Wahrnehmung und Akzeptanz religiöser Vielfalt in Europa. Veröffentlichungen der Sektion Religionssoziologie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, Lisa M. Stallworth, and Bertram F. Malle. 1994. Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 741–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebenstorf, Hilke. 2018. “Rechte” Christen?—Empirische Analysen zur Affinität christlich-religiöser und rechtspopulistischer Positionen. Zeitschrift für Religion, Gesellschaft und Politik 2: 313–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, Wilhelm. 1933. Die Massenpsychologie des Faschismus. Kopenhagen: Sexpol-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Riesebrodt, Martin. 1990. Fundamentalismus als patriarchalische Protestbewegung: Amerikanische Protestanten (1910–28) und iranische Schiiten (1961–79) im Vergleich. Tübingen: Mohr. [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers, Peer, Mèrove Gijsberts, Evelyn Hello, and Merove Gijsberts. 2002. Religiosity and Prejudice Against Ethnic Minorities in Europe: Cross-National Tests on a Controversial Relationship. Review of Religious Research 43: 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, Jim, and Felicia Pratto. 1999. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius, Jim, and Felicia Pratto. 2001. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression, 1. paperback ed. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney, and William S. Bainbridge. 1996. Religion, Deviance, and Social Control. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney, and Charles Y. Glock. 1968. American Piety: The Nature of Religious Commitment. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz, Jörg. 2000. Soziologie der Fremdenfeindlichkeit: Theoretische und empirische Analysen. Frankfurt a. M. New York: Campus. Univ., Diss. [Google Scholar]

- Stolz, Jörg. 2005. Explaining Islamophobia. A Test of Four Theories Based on the Case of a Swiss City. Swiss Journal of Sociology 31: 547–66. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1986. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Uenal, Fatih. 2016. Disentangling Islamophobia: The differential effects of symbolic, realistic, and terroristic threat perceptions as mediators between social dominance orientation and Islamophobia. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 4: 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 2005. America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity. Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yendell, Alexander. 2014. Warum die Bevölkerung Ostdeutschlands gegenüber Muslimen ablehnender reingestellt ist als die Bevölkerung Westdeutschlands. In Grenzen der Toleranz: Wahrnehmung und Akzeptanz religiöser Vielfalt in Europa. Veröffentlichungen der Sektion Religionssoziologie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie. Edited by Detlef Pollack, Olaf Müller, Gergely Rosta, Nils Friedrichs and Alexander Yendell. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yendell, Alexander, and Gert Pickel. 2019. Islamophobia and anti-Muslim feeling in Saxony – theoretical approaches and empirical findings based on population surveys. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zick, Andreas, and Beate Küpper. 2014. Schützt Religiosität vor Menschenfeindlichkeit oder befördert sie sie? In Was heißt hier Toleranz? Interdisziplinäre Zugänge. Edited by Andrea Bieler and Henning Wrogemann. Veröffentlichungen der Kirchlichen Hochschule Wuppertal/Bethel Bd. 15. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Theologie, pp. 146–63. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The fundamentalism scale that was used here was used successfully in the Bertelsmann Foundation’s international Religion Monitor (see Huber 2009, p. 28; Huber and Krech 2009, pp. 74–77). |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Beta | Beta | |

| Age | n.s | n.s. | n.s. |

| Sex | 0.148 *** | 0.075 * | n.s. |

| Education | 0.070 * | n.s. | n.s. |

| Political position | −0.227 *** | −0.116 ** | |

| Right-wing authoritarianism | −0.150 *** | −0.155 *** | |

| Social Dominance Orientation | −0.109 ** | −0.105 ** | |

| CRS | 0.262 *** | ||

| Religious fundamentalism | −0.364 *** | ||

| Secular threat | −0.245 ** | ||

| N | 882 | 840 | 746 |

| Corrected R² | 0.023 | 0.184 | 0.351 |

| Change R² | 0.161 | 0.167 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yendell, A.; Huber, S. The Relevance of the Centrality and Content of Religiosity for Explaining Islamophobia in Switzerland. Religions 2020, 11, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030129

Yendell A, Huber S. The Relevance of the Centrality and Content of Religiosity for Explaining Islamophobia in Switzerland. Religions. 2020; 11(3):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030129

Chicago/Turabian StyleYendell, Alexander, and Stefan Huber. 2020. "The Relevance of the Centrality and Content of Religiosity for Explaining Islamophobia in Switzerland" Religions 11, no. 3: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030129

APA StyleYendell, A., & Huber, S. (2020). The Relevance of the Centrality and Content of Religiosity for Explaining Islamophobia in Switzerland. Religions, 11(3), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030129