Abstract

This article is a follow-up on an earlier publication of a bi-lingual Greek-Samaritan inscription discovered at the site of Apollonia-Arsuf (Sozousa) in Area P1 in 2014. It presents the yet unpublished results of an additional season of excavations carried out in 2015 around the structure where the inscription was unearthed. This season of excavations aimed at locating the remains of a presumed Samaritan synagogue building that, in our view, musts have housed this bi-lingual Greek-Samaritan inscription.

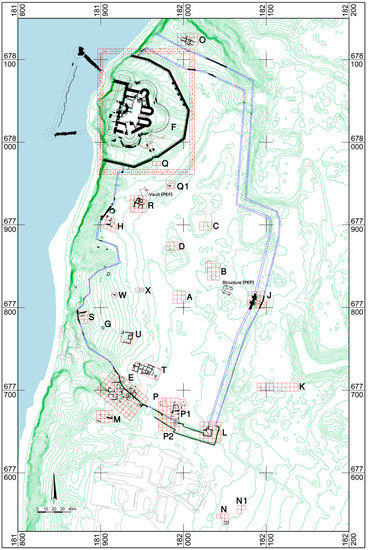

The site Apollonia-Arsuf is located on a fossilized sandstone dune ridge on the Mediterranean coast, in the north-western section of the town of Herzliya. Preliminary excavations of the site were carried out in 1950. Between 1977 and the present, it was excavated first on behalf of the Department of Antiquities and Museums and, from 1982, by the Institute of Archeology of Tel Aviv University under the direction of Israel Roll. Since 2006, Oren Tal has been the director of the excavations.1 The site was occupied continuously from the late sixth century BCE to the thirteenth century CE. Relatively meager architectural remains survived from the Persian and Hellenistic periods and these are confined to segments of walls, refuse pits, and a few burial sites. The most significant remains from the Roman occupation are those of a typical Roman peristyle type villa, surrounded by a peripheral corridor flanked with rooms. Byzantine Apollonia, called Sozousa, was unwalled and extended over an area of some 280 dunams. Among its published architectural remains are a church and industrial quarters with wine-presses, oil-presses, plastered pools, and raw glass furnaces. In the days of the Umayyad Caliph ‘Abd el-Malik (685–705) the site, at that point called Arsuf, was fortified by a wall that enclosed some 77 dunams. By the end of the Early Islamic period it became a ribbat (fort), where Muslim philosophers resided. In 1101 the site was conquered by the Crusaders. Towards the mid-twelfth century, ownership was transferred to a Crusader noble family and the site became the center of a feudal seigneury. Construction of the castle in the northern sector of the site began in 1241, and in 1261 administration of it, the town and the seigneury of Arsur (as it was now called) was passed on to the Knights Hospitaller. By the end of a Mamluk siege in 1265, the town and castle were destroyed and were never again settled (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Apollonia-Arsuf, site plan of the medieval walled town (with indication of areas of excavations) (Slava Pirsky).

The Byzantine-period settlement of Sozousa has been the subject of extensive and ongoing modern excavations and research for a long time now. Once a modest coastal settlement, Apollonia-Arsuf became the urban center of the southern Sharon Plain (at least its coastal strip) as early as the Persian period through the Crusader period. It is mentioned in a series of classical sources from the Roman period2, which mostly relate to Judaea’s coastal towns.

In written sources from the Byzantine period, it is recorded twice in the anonymous Cosmography of Ravenna in a list of urban centers of Iudaea-Palaestina3, where it appears after Caesarea and before Joppa, and again between Joppa and Caesarea in a long list of the coastal cities of Sinai and Palestine.4 Apollonia also appears in the detailed list of 25 cities of that name compiled by Stephanus Byzantius under number 13 ‘near Joppa’.5 On the other hand, Apollonia does not appear in early ecclesiastical lists. Two nineteenth-century scholars, Stark and Clermont-Ganneau, assumed that the reason for its absence is due to the fact that Apollonia’s name had been changed to Sozousa—a common change for cities named after Apollo Sōter in Byzantine times.6 Later texts and critical editions of texts, which recount the Persian-Sassanian capture of Jerusalem, record the death of the patriarch Modestus in a city named Sozos: Sozousa in Georgian texts, and Arsuf in Arabic texts.7 Official documents of the synod of Ephesus held in 449 CE indicate that in the mid-fifth century, Sozousa was a city in the Byzantine province of Palaestina Prima and that its Christian community was headed by a bishop. Bishops of Sozousa appear again in the records of two sixth-century ecclesiastical meetings.8 They may have served in the church with an inscribed mosaic floor that was uncovered in Apollonia in 1962 and 1976.9

The importance of Sozousa in late Byzantine Palestine (sixth–seventh centuries CE in archeological terms) seems to have been enhanced by the large and affluent Samaritan community that resided in the city until the Islamic conquest, as is evident from the archeological finds.10 Arsuf is also mentioned in connection with the Sassanian military campaign in the Holy Land.11 As there is no evidence of destruction, it may be assumed that the city surrendered peacefully to its Persian-Sassanian conquerors.12 The Acta Anastasii Persae relate that the escort conveying the relics of the Christian martyr Anastasius the Persian from Caesarea to Jerusalem in 631—soon after the Persians evacuated Palestine—marched via Sozousa. This indicates that the name Sozousa continued to be used for Apollonia-Arsuf until the Islamic conquest.13

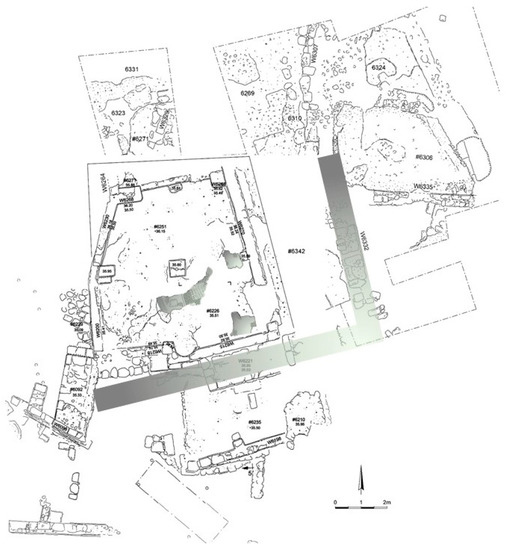

The Byzantine-period settlement has been the subject of research and excavations for a long time,14 and the current contribution will focus on one of the areas of excavations inside the walled town, designated Area P1 (Figure 2). Excavations were focused in this area because of its proximity to the medieval (Crusader-period) town wall, particularly to a point where a breach 21 m long can be seen (where I believe the Mamluk army destroyed the fortifications during the fighting in March 1265). This breach delimits the area on the south and the moat of the medieval fortifications can be seen right below it (Figure 3). Earlier excavations west of Area P1 and its proximity in Area P, carried out during the 2003, 2004, and 2006 seasons, unearthed findings that relate to the site’s Mamluk destruction (1265 CE).15

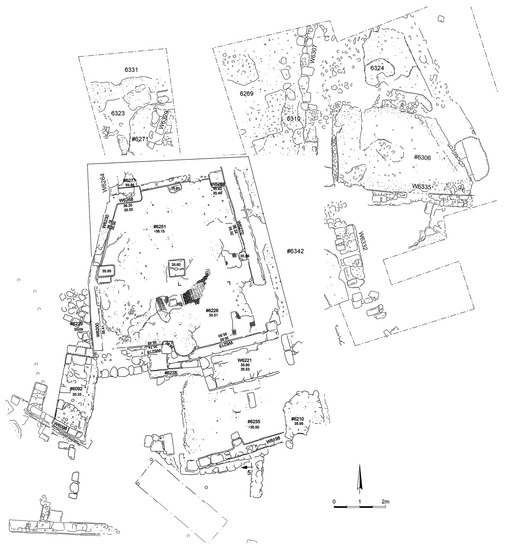

Figure 2.

Apollonia-Arsuf, plan of Area P1 (after the 2015 season of excavations) (Slava Pirsky).

Figure 3.

Apollonia-Arsuf, aerial photograph of the medieval walled town southern section (with indication of the southern fortifications and Area P1) (Or Fialkov).

In the framework of the 2014 season of excavations in Area P1, we have uncovered a bilingual Greek-Samaritan inscription (Figure 4).16 In what follows, I will provide a revised and augmented version of this discovery. It will be followed by an account of the results of the 2015 season of excavations in this area and their contribution to the reconstruction of a presumed Byzantine-period Samaritan synagogue therein.

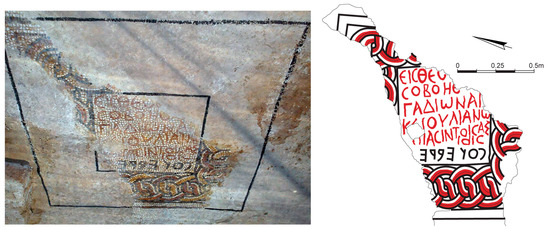

Figure 4.

Apollonia-Arsuf, Area P1, F6226, looking southwest (Pavel Shrago).

The inscription was unearthed set in a mosaic pavement consisting of medium to small white tesserae (1–1.5 cm on average) in a later hall whose floor and walls were plastered (#6226) (Figure 5). Hence the mosaic and the inscription that adorned it are only partially preserved. The plastered hall seems to belong to a structure whose character is unclear (Figure 4). It is trapezoid-shaped, ca. 7.5 × 6.5 m, with three pier bases crossing it in the center from east to west that were probably used to support its roof. An opening (ca. 2.7 m wide) is visible on the north; there may have been another opening on the east (ca. 1.5 m wide). A semicircular plastered niche (ca. 0.75 m long) is apparent on the south. Given all these features, it is tempting to suggest that the semicircular plastered niche excavated on its south side served as a miḥrab (a semicircular niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the direction of the qibla). While the height of its walls is somewhat unified (0.5 m), their thickness is uneven (0.3–1.0 m). The reason for this seems to be the reuse of earlier walls (some are probably contemporaneous with the mosaic pavement) especially in its southern part, where a plastered room (L6235) was unearthed whose construction and plastering is similar to that of the trapezoidal hall on its north. These two spaces were likely to have been part of the same building.

Figure 5.

Apollonia-Arsuf, Area P1, the inscription, photo (on left, after restoration) and drawing (on right; Slava Pirsky).

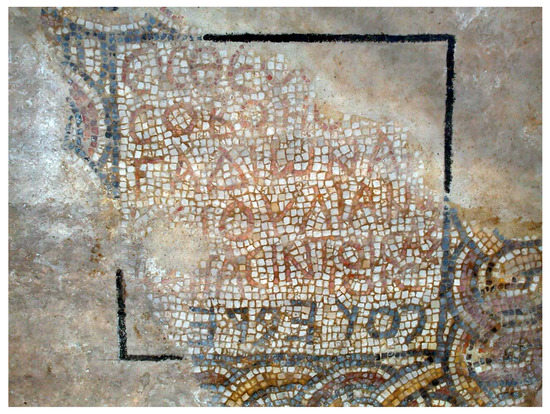

The mosaic was uncovered in the hall’s southern half with the inscription close to its center. It is rectangular, and double-framed with black tesserae (reconstructed dimensions are 1.3 × 1.4 m). It is aligned in an east-west orientation, that is, the person reading it would face east toward Mount Gerizim. Surrounding the single black frame around the inscription itself is a partially preserved tri-color (black, red, and white) guilloche-patterned frame (Figure 5 and Figure 6).17 It seems that the double-framed rectangular panel with the inscription in its center and the surrounding guilloche were encircled by a round medallion, of which only a small part has survived on the west. Our measurements show that neither the double-framed black rectangular panel nor the lines of the inscription are totally aligned; hence, we cannot exclude the possibility that parts of the mosaic pavement have slightly moved over the years. Moreover, small parts of the inscription were extracted from the floor in later periods and over time it was covered by whitewash that accumulated on the floor (unconnected to the later plastering). Nonetheless, the inscription itself was found to be almost complete.

Figure 6.

Apollonia-Arsuf, Area P1, the inscription, photo (close-up, after restoration).

The Greek letters were made of red tesserae and those of the Samaritan inscription were made of black tesserae. While the Greek inscription is composed of five rows (and an uneven additional row with the suffix of the last word), that of the Samaritan inscription has one row. Based on the division of the letters of both the Greek and the Samaritan, it seems that the craftsman who made the inscription was not highly skilled and its wording may have been changed (that is, expanded) while the work was underway.

As the inscription’s preservation is quite good and, as noted, was found almost complete, I was able to transcribe the letters in the following manner:

- EICΘEO …

- COBOHΘ̣ …

- ΓAΔΙWNAṆ

- K/IOYΛIANW

- ḲϵΠACΙΝΤOΙCAΞ

- ΙOΙC

Hence, the transliterated and restored version of the inscription may be read as follows:

- Εἷς θεὸ[ς μόνο-]

- ς ὁ βοηθ[ῶν]

- Γαδιωναν

- κ(αὶ) ᾿Ιουλιανῷ

- κ(αὶ) πᾶσιν τοῖς ἀξ-

- ίοις

- פעלהבדה

While the translation of the Greek is “One only god/who helps/Gadiona/and Iulianus/and all who deserve it”, that of the Aramaic (written in Samaritan script) may be translated as “(made it from his) possession in this place”.

The combination of Aramaic and Latin names as dedicators is interesting. The name Gadiona would apparently be the Greek transcription of the Semitic name *gdywn’. Hence it would represent an Aramaic form,18 known to have been used among Jews (and other ethnic groups) despite its theophoric (Ba‘al Gad) connotation.19 Iulianus was a common Latin name that was used among the different populations of Byzantine Palestine. Thus, encountering these names in a Samaritan context is not surprising.20

As for the Aramaic part, the third Samaritan letter from right may be read as -gimmel- but the root פעג has no meaning and would make no sense. The second Samaritan letter from left can be read as -resh- hence בדה—in this place—can also be read as ברה—his son but this seems less probable given the Greek content of the inscription where two private names are in the dative form as well as “all the righteous ones”.

Since p‘lh (פעלה), according to my understanding, is used as (an abbreviated) possessive pronoun in this context,21 the suggested translation “(made it from his) possession in this place” would relate to the building in which the inscription was placed. In this manner both parts of the inscription, the Greek and the Aramaic, not only interact with each other but also lack a verb that described the benefactors’ action, which was obviously clear to those who read the inscription while the building in which it was placed was still in use. The use of p‘lh as a possessive pronoun seems quite common, as can be seen for example in an Aramaic inscription from the synagogue at Korazim,22 and also from an Aramaic inscription on the mosaic pavement of the synagogue’s exedra at Eshtemoa‘.23 Like in our inscription, the inscription from the synagogue at Eshtemoa‘ seems to display p‘lh in a singular form despite plural benefactors.24

On the whole, the Samaritan letters as they appear in the inscription lack the common diagonal alignment seen, for example, in other Samaritan inscriptions on mosaic pavements (see below) and it either implies inexperienced craftsmanship or an earlier date (second half of the fourth century or less likely the early fifth century CE).25

It is beyond the scope of this paper to repeat my past arguments on the use of the Εἷς θεὸς μόνος formula inscriptions in Palestine and their exclusive Samaritan provenance. What can be said is that in a series of papers26 I have shown that these inscriptions are far fewer than the other Palestinian Εἷς θεός formula inscriptions,27 and that they are found in Roman and Byzantine sites in Samaria and in settlements where Samaritan communities are attested by both the archeological finds and the written sources.28

The current inscription from Apollonia/Sozousa is unique, as there are not many examples of bilingual Greek-Samaritan dedicatory inscriptions.29 The ones that we do know of are normally from synagogues (or assumed to have come from synagogues). The earliest evidence we have is the debased Ionic-style column capital from Emmaus-Nicopolis, found in secondary use in the floor of the northern aisle of the Crusader-period church, with the Εἷς θεός inscription on one side and ברוכשמו/לעולמ (his name is blessed forever) on the opposite side within a tabula ansata.30 Another instance of Greek and Samaritan inscriptions written together is the mosaic pavement of the synagogue at Sha‘alvim (Salbit); here the Greek and Samaritan inscriptions were separated from one another, yet appear on the same mosaic pavement.31 While the Samaritan inscription (יהוה/ימלוכ/לעולמ/ועד)—the Lord will reign forever and ever more; Exod. 15:18) was discovered in the central section of the northern part of the hall, in front of the place where the bemah and the Ark of the Law must have been, the two written in Greek were found in the center of the hall (a medallion) and more to the rear of it. A similar phenomenon of separated Greek and Samaritan inscriptions on the same mosaic pavement is also known from the Samaritan synagogue at Tell Qasile.32 Only one-third of the building survived. The Samaritan inscription was discovered in the central section of the southern aisle,33 while the two written in Greek were found close to the entrance.34 In this context, the inscription in Samaritan script from the room adjoining the synagogue of Beth-She’an/Scythopolis should be mentioned.35 Naveh has shown, however, that the text of this medallion inscription despite being written in Samaritan script is actually in the Greek language (קהריה/בותה/אפרי/קהיעננ—God help Ephrai[m] and Anan).36

With these comparanda in mind, we came back to the field in the summer of 2015 in order to find remains of a synagogue building around the inscription we have unearthed in 2014. We have extended the area of excavations to the north and west, and the total extent of Area P1 was now some 18 × 15.5 m, whereas the 2015 extension included some five (4 × 4 m) squares. The overall preservation of the archeological remains in the area was relatively poor, as the three northernmost and the three easternmost squares were right beneath an area that was occupied up until 2001 by an Israel Military Industries plant. These squares were located right beneath the plant driveway, an electric transformer and a fence. As such, these squares were found disturbed and clean of any secured archeological remains in the elevation we have reached. Still, other parts of the newly opened squares were mostly dominated by plaster floors (and floor foundations) that originally served plastered installations (e.g., F6271, F6306) delimited by fragmentary walls (e.g., W6329, W6335) (Figure 2) dated to the Early Islamic period.

Among the remains we have unearthed was a wall (W6332) built in a north-south orientation, discovered in the central part of the area we opened in 2015, some 5.5 m north of the mosaic inscription (Figure 7). It was found located in alignment with the inscription and perpendicular to yet another wall (W6221), built in an east-west orientation. Both of these walls were constructed using a similar building technique, especially in their lower courses. Fossilized dune bossed stones and ashlars laid in leveled courses and consolidated with fieldstones and muddy mortar. The depth of the foundations of these walls (W6332, W6221) and their preserved elevations may suggest that the lower courses served the eastern and southern walls of the hall whose floor served the mosaic inscription. It may be added that the lower courses stones of the corner between these walls were robbed as is attested by a robber trench we detected therein (Figure 7: 2). Still, it is clear that the upper courses of these walls belong to later constructions and that the fragmented nature of the area prevents us from understanding their later use.

Figure 7.

Apollonia-Arsuf, Area P1. (1) Wall 6332, looking east. (2) Wall 6221 (top), Wall 6332 (center), with an arrow marking the assumed corner, looking south (Pavel Shrago).

Thus, the lower courses of walls W6332 and W6221 and the remains of the mosaic floor with its recovered inscription allow us to suggest that all these features form part of the main hall of a Samaritan synagogue, whose east-west orientation faced Mount Gerizim (Figure 8). This presumed synagogue may be added to the list of Samaritan synagogues outside Samaria, as mentioned above (namely, Tell Qasile [Eretz Israel Museum], Sha‘alvim, Beth-She’an/Scythopolis and Raqit).37 The alignment of the inscription toward Mount Gerizim lends support to such a conclusion.

Figure 8.

Apollonia-Arsuf, plan of Area P1, with an indication of architectural remains of the Byzantine-period presumed synagogue building.

The date of construction of this presumed synagogue can be assigned either to the fourth or to the fifth century CE. This dating is based on the earliest fragments of pottery and glass vessels recovered in fills below the walls in the area (excluding some isolated earlier finds). As these fills were discovered disturbed and the southern part of the site (as excavated in Areas E-north, K, L, M, N, N1, P, P1, P2, U and T, see Figure 1) does not show evidence of an earlier occupation prior to the fourth century,38 I tend to assign the Samaritan building activity to that period of time as backed by the paleography of the inscription’s Samaritan letters. Moreover, the earliest coins unearthed in the area and its close environs (Area P) are dated to the third and fourth century CE. Furthermore, the style of the mosaic motif (shaded, four-strand guilloche) and the paleography of the Greek letters fully support such a date.

The building was destroyed (or abandoned) sometime in the later part of the Byzantine period or the early part of the Early Islamic period. The plastered walls and the floor of the hall (#6226) were probably constructed in the seventh or eighth century CE. This dating is based on the finds recovered in relation to their construction. They provide us with a terminus ante quem for the point in time when the presumed synagogue building ceased to be used, namely any date between the fourth and the seventh century CE. It is tempting to suggest that the synagogue was destroyed in the context of the promulgation of Justinian’s law (ca. 527–531 CE) prohibiting Samaritan gatherings of any kind, as I have suggested elsewhere with regard to another area we have excavated at the site.39 Justinian’s encouragement to destroy Samaritan synagogues (Samaritarum synagogae destruuntur)40 may have been the historical setting for the destruction of this synagogue. Unfortunately, we have no archeological evidence to support such a hypothesis.

Still, one should bear in mind that the excavations were limited and the area is largely disturbed due the occupations in both the Byzantine period and the Early Islamic period. If our above identification of the semicircular plastered niche in the hall (#6226) as a miḥrab is indeed correct, the suggestion is plausible that we have here an earlier cult place, i.e., a presumed Samaritan synagogue, that was transformed into another cult place. i.e., a mosque, either immediately after the synagogue went out of use or after a hiatus in which the building stood empty.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Primary Sources

Schwartz, E., ed. 1940. Acta Conciliorum Oecomenicorum. Berlin: W. de Gruyter, vol. III.Straub, J., ed. 1971. Acta Conciliorum Oecomenicorum. Berlin: W. de Gruyter, vol. IV.CIIP. Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae Palaestinae. 2010–. Berlin: W. De Gruyter.Krueger, P., ed. 1877. Codex Iustinianus. Berlin: Corpus Iuris Civilis, vol. 2.Itineraria Romana, L. Schnetz, ed. 1940. Cosmography of Ravenna. In Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia et Guidonis Geographica. Leipzig: Friderici Nicolai, vol. II.Yarnold, E. S. J., ed. 2000. Catecheses. In Cyril of Jerusalem. London and New York: Routledge.Garitte, G., ed. 1953. Expugnationis Hierosolymae A.D. 614, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 341, Scriptores Arabici 27. Louvain: Secretariat du Corpus SCO.Garitte, G., ed. 1974. Expugnationis Hierosolymae A.D. 614, Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 348, Scriptores Arabici 29. Louvain: Secretariat du Corpus SCO.Flavius, Josephus, and Jewish Antiquities. 1980. Books XII–XII. Translated by Marcus, R. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. V, LCL 365.Garitte, G., ed. 1960. La prise de Jerusalem par les Perses en 614. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 203, Scriptores Iberici 12. Louvain: Secretariat du Corpus SCO.House, C. 1888. Life of George of Choziba. Vita Sancti Georgii Chozibitae auctorae Antonino Chozibita. Analecta Bollandiana 7: 95–144.Pliny. 1906. Plini Secundi Naturalis Historiae. Edited by Mayhoff, C. Leipzig: Teubner, vol. I.Ptolemy. 1901. Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia. Edited by Muller, C. (revised Edited by Fischer, C. T.). Paris: A. Firmin-Didot [n.p.], vol. II.SEG. Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum. 1923–. Leiden: Brill.Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History. 1890. The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen, Comprising a History of the Church from A.D. 323 to A.D. 425. Translated by Hartranft, C. D. Buffalo: Christian Literature Publishing Co.Billerbeck, M., ed. 2006. Stephani Byzantii Ethnica. Berlin and New York: W. de Gruyter, vol. I.Meineke, A., ed. 1849. Stephani Byzantii Ethnicorum Quae Supersunt. Berlin: G. Reimer.References

- Ashkenazi, Dana, Oz Golan, and Oren Tal. 2013. An Archaeometallurgical Study of 13th-Century Arrowheads and Bolts from the Crusader Castle of Arsuf/Arsur. Archaeometry 55: 235–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmelle, Catherine, ed. 1985. Le décor géométrique de la mosaïque romaine. In Répertoire Graphique et Descriptif des Compositions Linéaires et Isotropes. Paris: Piccard, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Barag, Dan. 2009. Samaritan Writing and Writings. In From Hellenism to Islam: Cultural and Linguistic Change in the Roman Near East. Edited by Hannah M. Cotton, Robert G. Hoyland, Jonathan J. Price and David J. Wasserstein. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 303–23. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Klaus. 1984. Die aramäischen Texte vom Toten Meer: samt den Inschriften aus Palästina, dem Testament Levis aus der Kairoer Genisa, der Fastenrolle und den alten talmudischen Zitaten. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, Rachel, and Asher Ovadiah. 1990. A Greek Inscription from the Early Byzantine Church at Apollonia. IEJ 40: 182–91. [Google Scholar]

- Clermont-Ganneau, Charles. 1882. Note II, Expedition to Amwas (Emmaus-Nicopolis). Palestine Exploration Fund, Quarterly Statement 14: 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Clermont-Ganneau, Charles. 1896. Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873–1874. London: Palestine Exploration Fund, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dilke, O.A.W. 1985. Greek and Roman Maps. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Di Segni, Leah. 1994. Εἷς θεός in Palestinian Inscriptions. SCI 13: 94–115. [Google Scholar]

- Di Segni, Leah. 2002. Samaritan Revolts in Byzantine Palestine. In The Samaritans. Edited by Ephraim Stern and Hanan Eshel. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi Press, pp. 467–80. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Di Segni, Leah. 2004. Two Greek Inscriptions at Horvat Raqit. In Raqit: Marinus’ Estate on the Carmel, Israel. Edited by Shimon Dar. BAR International Series 1300; Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 196–98. [Google Scholar]

- Flusin, Bernard, ed. 1992. Saint Anastase le Perse et l’histoire de la Palestine au debut du VIIe siècle. Paris: Éd. du CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Friedheim, Emmanuel. 2002. The Names “Gad”, “Gadda” and “Gadya” among Palestinians and Babylonian Sages, and the Rabbinic Struggle against Pagan Influences. In These Are the Names: Studies in Jewish Onomastics. Edited by Aaron Demsky. Ramat-Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, vol. 3, pp. 117–26, (In Hebrew, English summary p. 147). [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, Tal. 2002–2012. Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity, part I–IV. Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum 91, 126, 141, 146. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Haya. 1978. A Samaritan Church on the Premises of ‘Museum Haaretz’. Qadmoniot 42–43: 78–80. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Rubin, Milka. 2002. The Continuatio of the Samaritan Chronicle of Abū L-Fatḥ Al-Sāmirī Al-Danafī. Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 10. Princeton: Darwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitzhak. 2008. The Samaritans and the Good Samaritan. Judea & Samaria Publications 7. Jerusalem: Staff Officer of Archaeology—Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria. [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitzhak. 2010. The Good Samaritan Museum. Judea & Samaria Publications 12. Jerusalem: Staff Officer of Archaeology—Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria. [Google Scholar]

- Ma‘oz, Zvi Uri. 2010a. Baniyas and Baal-Gad “below Mt Hermon” (Josh 11:17). Transeuphratène 39: 113–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ma‘oz, Zvi Uri. 2010b. Interpretatio Graeca: The Case of Gad and Tyché. Qazrin: Archaostyle. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Joseph. 1978. On Stone and Mosaic: The Aramaic and Hebrew Inscriptions from Ancient Synagogues. Jerusalem: Karta/Israel Exploration Society. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Joseph. 1981. A Greek Dedication in Samaritan Letters. IEJ 31: 220–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ovadiah, Ruth, and Asher Ovadiah. 1987. Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine Mosaic Pavements in Israel. Rome: «L’Erma» di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Patrich, Joseph. 1999. The Warehouse Complex and Governor’s Palace (Areas KK, CC, and NN, May 1993–December 1995). In Caesarea Papers. Edited by Kenneth G. Holum, Avner Raban and Joseph Patrich. JRA Supplement Series 35; Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 2, pp. 70–108. [Google Scholar]

- Patrich, Joseph. 2001. Urban Space in Caesarea Maritima, Israel. In Urban Centers and Rural Contexts in Late Antiquity. Edited by Thomas S. Burns and John W. Eadie. Michigan: East Lansing, pp. 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, Paul. 1923–1924. La Prise de Jerusalem par les Perses. Melanges de l’Universite Saint Joseph de Beyrouth 9: 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Erik. 1926. Εἷς θεός: Epigraphische, Formgeschichtliche und Religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen. Göttingen: Vandenhoek und Ruppreeht. [Google Scholar]

- Rabello, Mordechai Alfredo. 1991. The Samaritans in Justinian’s Code I, 5. In Proceedings of the First International Congress of the Société d’Études Samaritaines, Tel Aviv, April 11–13, 1988. Edited by Avraham Tal and Moshe Florentin. Tel Aviv: Chaim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies, Tel Aviv University, pp. 139–46. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Ronny. 1994. The Plan of the Samaritan Synagogue at Sha‘alvim. IEJ 44: 228–33. [Google Scholar]

- Roll, Israel. 1999. Introduction: History of the Site, Its Research and Excavations. In Apollonia-Arsuf: Final Report of the Excavations, vol. I: The Persian and Hellenistic Periods (with Appendices on the Chalcolithic and Iron Age II Remains). Edited by Israel Roll and Oren Tal. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 16; Tel Aviv: Emery and Clair Yass Publications in Archaeology, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Roll, Israel, and Etan Ayalon. 1989. Apollonia and Southern Sharon: Model of a Coastal City and Its Hinterland. Tel Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuchad. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Roll, Israel, and Oren Tal. 2008. A New Greek Inscription from Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf/Sozousa: A Reassessment of the Εἷς Θεὸς Μόνος Inscriptions of Palestine. SCI 28: 139–47. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, Robert. 1995. The Christian Communities of Palestine from Byzantine to Islamic Rule: A Historical and Archaeological Study. Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 2. Princeton: Darwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schnetz, Joseph. 1942. Untersuchungen uber die Quellen der Cosmographie des anonymen Geographen von Ravenna. Sitzungsberichte der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Abteilung 6: 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Karl Bernhard. 1852. Gaza und die Philistaische Kuste. Jena: F. Mauke. [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik, Eliezer L. 1949. The Samaritan Synagogue at Salbit, Preliminary Report. Bulletin of the L. M. Rabinowitz Fund for the Exploration of Ancient Synagogues 3: 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Oren. 2009. A Winepress at Apollonia-Arsuf: More Evidence on the Samaritan Presence in Roman-Byzantine Southern Sharon. Liber Annuus 59: 319–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, Oren. 2015. A Bilingual Greek-Samaritan Inscription from Apollonia-Arsuf/Sozousa: Yet More Evidence of the Use of εἷς θεὸς μόνος Formula Inscriptions among the Samaritans. ZPE 194: 169–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Oren. 2020. Apollonia-Arsuf: Final Report of the Excavations. Volume II: Excavations outside the Medieval Town Walls. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 38. Tel Aviv/University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Oren, and Gabriella Bijovsky. 2017. A Hoard of Fourth-Fifth Century CE Copper Coins from Sozousa. INR 12: 147–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Oren, and Israel Roll. 2011. Arsur: The Site, Settlement and Crusader Castle, and the Material Manifestation of Their Destruction. In The Last Supper at Apollonia: The Final Days of the Crusader Castle in Herzliya. Edited by Oren Tal. Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum, pp. 8–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Oren, and Israel Roll. 2018. The Roman Villa at Apollonia (Israel). In The Roman Villa in the Mediterranean Basin. Edited by Guy P. R. Métraux and Annalisa Marzano. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 308–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Oren, and Itamar Taxel. 2012. Socio-Political and Economic Aspects of Refuse Disposal in Late Byzantine and Early Islamic Palestine. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 12–16 April 2010. Edited by Roger Matthews and John Curtis. with the collaboration of Michael Seymour, Alexandra Fletcher, Alison Gascoigne, Claudia Glatz, St John Simpson, Helen Taylor, Jonathan Tubb and Rupert Chapman. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co., pp. 497–518. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Oren, and Itamar Taxel. 2015. Samaritan Cemeteries and Tombs in the Central Coastal Plain: Archaeology and History of the Samaritan Settlement outside Samaria (ca. 300–700 CE). Agypten und Altes Testament 82. Munster: Ugarit Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Yeivin, Ze’ev. 2000. The Synagogue at Korazim: The 1962–1964, 1980–1987 Excavations. IAA Reports 10. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority. [Google Scholar]

- Yeivin, Ze’ev. 2004. The Synagogue at Eshtemo’a in Light of the 1969 Excavations. Atiqot 48: 59–98, (In Hebrew, English summary pp. 155–58). [Google Scholar]

- Zadok, Ran. 1987. Zur Struktur der nachbiblischen jüdischen Personennamen semitischen Ursprungs. Trumah 1: 243–343. [Google Scholar]

- Zori, Nehemiah. 1967. The Ancient Synagogue at Beth-Shean. Eretz-Israel 8: 149–67, (In Hebrew, English summary p. 73). [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities XIII, 395; Pliny the Elder, Natural History 5.69; Ptolemy, Geography 5.15.2. |

| 3 | 2.14.2 and 5.7.2, Itineraria Romana, ed. by Schnetz, II, 25, 90, and 133. |

| 4 | The Cosmography of Ravenna was compiled soon after 700 CE from earlier sources that go back to early Byzantine or even Roman times (see Schnetz 1942; Dilke 1985, pp. 174–76). |

| 5 | Stephani Byzantii Ethnicorum quae supersunt, ed. by Meineke, p. 106. It is worth noting that in Stephanus Byzantius’s text, the name Sozousa (s.v. no. 1, p. 596) is also mentioned (see below) most probably because Stephanus used sources from different periods: one from Roman times when listing Apollonia, and a second source from Byzantine times when mentioning Sozousa. For Apollonia, see also Stephani Byzantii Ethnica, I, 228–29. |

| 6 | (Stark 1852, p. 452 note 5; Clermont-Ganneau 1896, II, pp. 337–39). |

| 7 | La prise de Jérusalem, ed. Garitte, p. 55; Expugnationis Hierosolymae, ed. Garitte, 341, pp. 38, 70; 348, p. 131. |

| 8 | Acta conciliorum oecomenicorum, III, ed. Schwartz, pp. 80, 188, and IV, ed. Schwartz, no. 1, p. 221. |

| 9 | (Birnbaum and Ovadiah 1990; Roll 1999, pp. 31, 45). |

| 10 | ((Tal 2020), with reference to earlier publications on the subject). It should be emphasized, however, that Abū l-Fatḥ reports Samaritan synagogues in villages between Zaytā (north of Ṭūl Karem) and Arsūf, but only a Dosithean (not Samaritan) ‘meeting place’ in Arsuf in the early ninth century, long after the Islamic conquest (cf. Levy-Rubin 2002, pp. 69 f). |

| 11 | (Peeters 1923–1924, p. 13); La prise de Jerusalem, ed. Garitte, pp. 4, 42; Expugnationis Hierosolymae, ed. Garitte 348, pp. 75, 104; see also (Schick 1995, pp. 20–25). |

| 12 | ((Schick 1995, p. 250); for the archeological evidence cf. (Tal and Taxel 2012, pp. 499–501; Tal and Bijovsky 2017)). |

| 13 | (Flusin 1992, I, p. 105, II, p. 339). |

| 14 | (Roll and Ayalon 1989, pp. 51–67; Roll 1999; Tal 2020). |

| 15 | Area P’s main discovery was a formidable platform built into earlier strata and dated to the end of the Crusader period, assumed to have served Crusader artillery; see in this respect, (Tal and Roll 2011, pp. 37–38) in the English section). As the walled medieval town site forms part of the Apollonia National Park (as of 2001), originally the architects of the park planned a bridge across the medieval town southern fortifications moat on which a pathway for the disabled will serve the entrance into the walled town. Thus, the preliminary excavations on both sides of the moat (in Area P1 and Area P2) were carried out in 2012 in the context of this bridge foundations. It may be added that Area P1’s upper level is mostly characterized by thick white mortar surfaces (to facilitate Crusader maneuvering), in which many thirteenth-century arrowheads were found, similar to those unearthed in the Crusader castle, attesting to the fierce fight with the Mamluks (on the latter, see Ashkenazi et al. 2013). Area P2 revealed no substantial findings apart from the moat’s external (southern) fortification wall. |

| 16 | (Tal 2015). |

| 17 | The motif as depicted around the inscription can be defined as a shaded, four-strand guilloche on a white ground (see e.g., Balmelle 1985, pl. 73c). It is more familiar in fifth- and sixth-century CE mosaic pavements in the region (see for example Ovadiah and Ovadiah 1987, p. 202, motif B4). |

| 18 | Like Sergonas from Sergius/Sergas. In Byzantine-period contexts -gd- means luck, hence the personal name Gadiona may represent the manifestation of a good fortune (on the etymology of the name Gad, see (Friedheim 2002, pp. 117–26; Ma‘oz 2010a, 2010b)). |

| 19 | (see e.g., (Zadok 1987, p. 280, §2.1.10.4.1 and p. 300, §2.2.6.2 [with non-Greek bases, viz. Semitic, Iranian and Latin]; Ilan 2002–2012, I [Palestine 330 BCE–200 CE], pp. 366–67; 2012, II [Palestine 200–650 CE], p. 334; 2008, III [The Western Diaspora 330 BCE–650 CE], p. 668; 2011, IV [The Eastern Diaspora 330 BCE–650 CE], pp. 341–42 for comparanda)). |

| 20 | The two καί are written in abbreviated form, the first is apparently -κ- with an abbreviation mark in the form of a diagonal stroke; the second seems to have been written as -κϵ-, with a round-backed epsilon. |

| 21 | Originally a qutl-formation meaning “possession” in Jewish Aramaic + the possessive suffix 3rd sg. masc. -hé- (and -hé-, -waw-, -nun- for 3rd plur. masc.) (cf. Beyer 1984, p. 669). |

| 22 | The inscription is engraved on the frontal base of a decorated stone chair. It reads: דכיר לטב יודנ בר ישמעאל / דעבד הדנ סטוה / ודרגוה מפעליה יהי / לה חולק עם צדיקיה – for the good remembrance of Yodan Bar Ishmael who made this portico(?) and stairs from his possession, may it be shared with its righteous (cf. Beyer 1984, pp. 382–83; see also Naveh 1978, pp. 36–38, no. 17). Given the archeological data the synagogue is dated to either the fourth or the fifth century CE (see Yeivin 2000, p. 106), English summary 30*–31*. |

| 23 | The inscription reads: דכיר לטב לעזר כהנאׄ / ובנוי דיהב חד טר[י]/ [מ]יסינ מנ פעל[ה] – for the good remembrance of Lezer the Priest and his sons who gave one tremisis [one-third of a gold solidus] from his possession (cf. Beyer 1984, p. 365; Naveh 1978, p. 114, no. 74). The synagogue is dated to either the third or the fourth century CE (see Yeivin 2004). |

| 24 | Still, as our example is abbreviated, it may well represent the plural form of this possessive pronoun, that is, p‘lhwn. |

| 25 | Moreover, most of the letters in our inscription are not as typical as they appear on other such pavements (but examples are numbered); the -pé-, -‘ayin-, -beth- and -daleth/resh- are rounded rather than rectangular, the -lamed- is inverted (unless it is a -gimmel- and the word is then meaningless as stated above) and the -hé- is vertically aligned rather than diagonally. Still, quite a similar -pé- and -‘ayin- are known, for example, from the Beth-She’an synagogue (below). |

| 26 | ((Roll and Tal 2008; Tal 2009); see also SEG 59, no. 1704, where my interpretation of the formula as Samaritan is given by the editors; and more specifically (Tal 2015)). |

| 27 | (See in this respect (Di Segni 1994, pp. 100–1), nos. 16, 20a, Formula C on p. 111). To these we may add ((Patrich 1999, p. 97; Patrich 2001, p. 81, note 17). See also SEG 49, no. 2054). Another such formula is known from Raqit in the Carmel where it is ascribed to a Samaritan synagogue ((Di Segni 2004, pp. 196–97); see also SEG 55, no. 1731). |

| 28 | It may also be added that I believe I have raised convincible doubts against attempts to assign them to other groups of monotheistic faith. (Contra Peterson 1926), esp. pp. 196, 256; and also CIIP, II: Caesarea and the Middle Coast 1121–2160, Berlin 2011, no. 1342. |

| 29 | There are of course many bilingual amulets but these are beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 30 | As published by (Clermont-Ganneau 1882); and more recently by ((Barag 2009, pp. 311–14) for its history of research and revised dating in the fifth–sixth centuries CE). |

| 31 | ((Sukenik 1949, pp. 25–30; esp. p. 29, pl. XV); see also (Reich 1994); and (Magen 2010, pp. 164–65)). |

| 32 | (Kaplan 1978). |

| 33 | It reads: מכסימ / תכיר דקר / פרקסנה / תכיר דקר – Maximus/ona is/will be remembered for he/she donated/is honored. Proxena/Priscianus is/will be remembered for she/he donated/is honored; after A. Yardeni’s compromise translation in the CIIP, III (South Coast 2161–2648), no. 2168. The date of the inscriptions discovered in the building on the same mosaic pavement is incoherent. On the one hand, the editors apparently accepted the excavator’s later dating, and accordingly dated one of the two Greek inscriptions to the sixth–seventh centuries (no. 2167 [by J. J. Price]), while the other Greek inscription was left undated (no. 2166 [by W. Eck]). On the other hand, A. Yardeni dated the Samaritan inscription to the fifth century (no. 2168). In any case, the decoration of the mosaic pavement agrees more with the earlier dating. An earlier dating is also supported by the finds that came from the foundations of the synagogue (see Tal and Taxel 2015, Appendix I.3, pp. 209–13). |

| 34 | Interestingly, the color of the Samaritan letters in all mosaic pavements that exhibit Samaritan and Greek inscriptions is normally black (or dark gray) while that of the Greek letters is normally red. |

| 35 | (Zori 1967). |

| 36 | (Naveh 1981). |

| 37 | Visit http://synagogues.kinneret.ac.il/excavated-synagogues/synagogues-interactive-map/ (for Samaria see also Magen 2008, pp. 117–80). |

| 38 | See in this respect (Tal and Bijovsky 2017, pp. 155–56). An exception is Area E-south, a mansio of the Early Roman period, that stood alone at the site at the time (see Tal and Roll 2018, pp. 313–14). |

| 39 | At Area O in the north part of the site, a winepress featuring a dedicatory Samaritan inscription written in Greek on its treading floor that was found intentionally filled with refuse dated to the mid-sixth century CE (see Tal 2009; 2020, pp. 70–80). |

| 40 | Codex Iustianus (ed. Krueger) 1.15.17; see also (Rabello 1991; Di Segni 2002). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).