Abstract

This study shows how Varanasi, a site that many people understand to be a sacred Hindu city, has been made “Jain” through its association with the lives of four of the twenty-four enlightened founders of Jainism, the jinas or tīrthaṅkaras. It provides an overview of the Jain sites of worship in Varanasi, focusing especially on how events in the life of the twenty-third tīrthaṅkara Pārśva were placed in the city from the early modern period to the present day in order to bring Jain wealth and resources to the city. It examines the temple-building programs of two Śvetāmbara renunciants in particular: the temple-dwelling Kuśalacandrasūri of the Kharataragaccha (initiated in 1778), and the itinerant Ācārya Rājayaśasūri of the Tapāgaccha (b. 1945). While scholars and practitioners often make a strong distinction between the temple-dwelling monks (yatis) who led the Śvetāmbara community in the early modern period and the peripatetic monks (munis) who emerged after reforms in the late nineteenth-century—casting the former as clerics and the latter as true renunciants—ultimately, the lifestyles of Kuśalacandrasūri and Rājayaśasūri appear to be quite similar. Both these men have drawn upon the wealth of Jain merchants and texts—the biographies of Pārśva—to establish their lineage’s presence in Varanasi through massive temple-building projects.

Keywords:

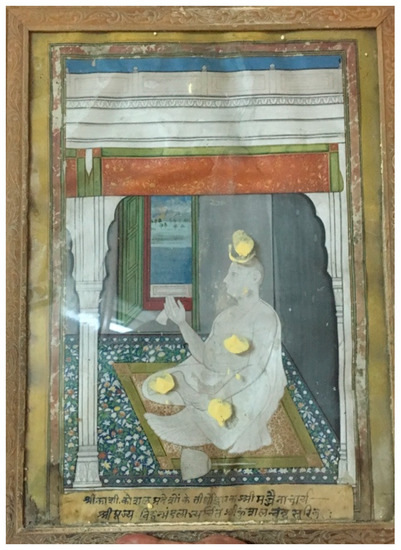

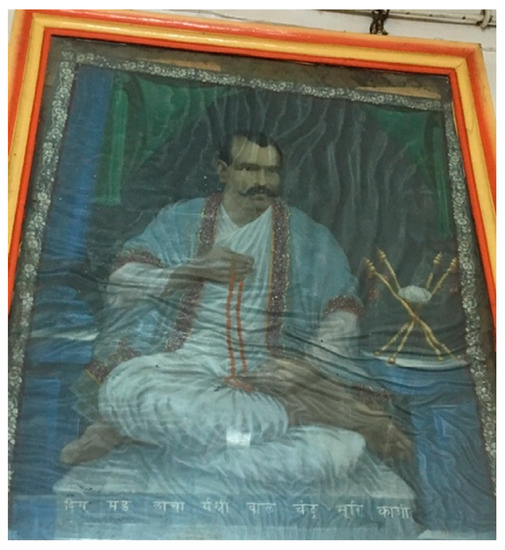

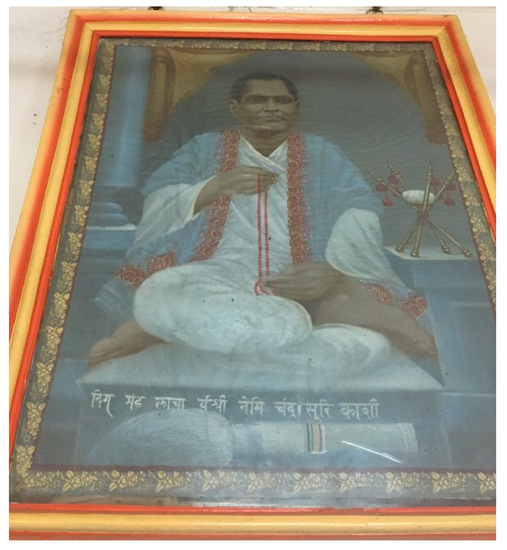

Jainism; Varanasi; biography; sacred space; monasticism; temple-building; Pārśva; Padmāvatī On the banks of the river Ganges, just south of Pañcagaṅgā Ghāṭ in the holy city of Varanasi, a small shrine to the snake goddess Padmāvatī sits in the basement of an early nineteenth-century Śvetāmbara Jain temple as a testament to an unsuccessful attempt to establish this area of Varanasi as a flourishing site of Jain worship (Figure 1). This shrine, inside the Śvetāmbara Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth temple near Rām Ghāṭ,1 celebrated its 200-year anniversary in March of 2014,2 and it is said to mark the exact spot where the twenty-third tīrthaṅkara Pārśva saved a pair of snakes from a tortuous death inside the fires of an immoral ascetic. It was commissioned by the temple-dwelling monk (yati) Ācārya Kuśalacandrasūri of the Diṅmaṇḍalācārya branch (śākhā) of the mendicant lineage the Kharataragaccha (Figure 2). Kuśalacandrasūri was initiated in Varanasi in 1778 and spent his entire life as a yati in the Rām Ghāṭ temple,3 overseeing its library of Jain manuscripts and the construction, restoration, and maintenance of five temples in and around the city. From 1778 to 1966, when the last temple-dwelling monk of Kuśalacandrasūri’s lineage, Ācārya Hīrācandrasūri, passed away, this temple at Rām Ghāṭ continued to be the main residence for yatis in Varanasi and a center for Śvetāmbara Jainism (Vinayasāgara 2004, p. 326). Today, however, few Jains visit the temple, and the early nineteenth-century mural that once covered the entirety of the wall behind the shrine to Padmāvatī has now been painted over and replaced with an unsophisticated scene of Pārśva saving the snakes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Padmāvatī shrine in the Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth temple near Rām Ghāṭ, Varanasi. Nineteenth Century.

Figure 2.

Nineteenth-century painting of Kuśalacandrasūri seated in the lecture hall of the Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth Temple at Rām Ghāṭ, with the door open to the Ganges behind him. This painting is established in a shrine in the lecture hall (upāśraya) of the temple, so it has been dapped with sandalwood paste.

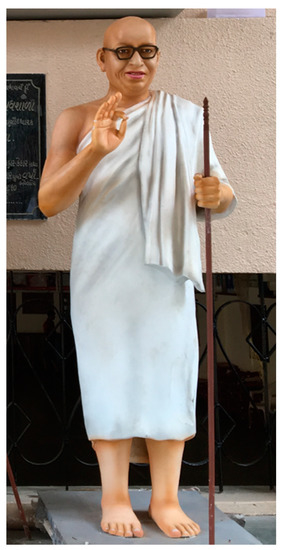

Across town, however, in the center of Varanasi, in Bhelūpur, at the supposed site of the conception, birth, enlightenment, and renunciation of Pārśva, a massive, thriving Śvetāmbara temple of red sandstone and white marble flourishes. The temple was designed in Māru-Gurjara (Solaṅkī) style4 by the Gujarati Chandrakant Somapura, the architect of a proposed Ram Janmabhūmi Temple in Ayodhya and the Akshardham Temple in Gandhinagar,5 and it was commissioned by a Gujarati monk who is rarely in Varanasi and has rejected living in temples, Ācārya Rājayaśasūri (b. 1945) of the mendicant lineage the Tapāgaccha (Figure 3). On November 17, 2000, after nine years of construction involving upwards of 200 workers, Ācārya Rājayaśasūri led the consecration of the temple, but his vow to live a peripatetic lifestyle meant that he did not take permanent residence in this temple, or in any of the many other temples he has commissioned in the last few decades (Singh and Rana 2002, pp. 205–7). Despite the lack of permanent mendicant presence at the temple, however, it has become the center for Śvetāmbara Jainism in Varanasi, greeting the most Śvetāmbara visitors of any temple in the city, housing the offices of the Śvetāmbar Tīrth Society that oversees most of the Śvetāmbara temples in the city, and hosting upwards of 9000 pilgrims a year in its adjoined guest house (dharmaśālā) with 40 rooms.6

Figure 3.

Statue of Ācārya Rājayaśasūri established in Ahmedabad for his rainy season retreat in 2016.

This essay looks at how these two temples arrived at their current statuses. It examines the successes and failures of Jain monks who have attempted to claim power over areas in and around Varanasi by commissioning temples associated with events in the lives of four of the twenty-four enlightened founders of Jainism, the tīrthaṅkaras: Supārśva (7th), Candraprabha (8th), Śreyāṃsa (11th), and, in particular, Pārśva (23rd). Varanasi includes places of worship from all the main sects of Jainism, including temples of the two main image-worshipping sects of Jainism—the Śvetāmbara, whose monks wear white robes, and the Digambara, whose monks today are nude. Amongst Śvetāmbaras, however, two monks have been especially influential in temple-building campaigns: Kuśalacandrasūri and Rājayaśasūri.

By the nineteenth century when Kuśalacandrasūri lived in Varanasi, Śvetāmbara Jainism was led by temple-dwelling monks (yati, caityavāsin, śrīpūjya).7 These monks, like their equivalents in Digambara communities, the bhaṭṭārakas, took permanent residence in the temple complexes they owned (Cort 2001, pp. 43–45), and for much of Jain history, they had led Jain communities.8 At the end of the nineteenth century, however, members of the Śvetāmbara mendicant lineage, the Tapāgaccha, rejected these yatis and re-established groups of itinerant saṁvegī sādhus who, other than during the four-month long rainy season, could only spend a few days at a time in one location (Cort 2001, pp. 45–46; Flügel 2006, pp. 317–25). Today, only a handful of yatis remain (Flügel 2006, p. 319), and scholars have essentially agreed with the nineteenth-century reformers, who took pains to distinguish themselves from their temple-dwelling predecessors and to define themselves as the “true” Jain mendicants who uphold the fifth mendicant vow of non-possession (aparigraha). In English-language scholarship, saṃvegī sādhus like the contemporary Rājayaśasūri are often called “mendicants” or “ascetics,” while temple-dwelling yatis like Kuśalacandrasūri are often understood to be “clerics” (e.g., Dundas 2002, p. 152; Laidlaw 1995, p. 398). This suggests that yatis are primarily in charge of ritual and bureaucratic leadership, while saṃvegī sādhus are austere renouncers, less connected to worldly matters such as temple rituals and the control of money. We should, however, find inspiration from Tillo Detige’s recent work (e.g., Detige 2019a, 2019b) on the continuities between clothed, sedentary early modern Digambara bhaṭṭārakas and naked peripatetic modern Digambara monks to examine the similarities between Śvetāmbara yatis and sādhus. As we will see in this study, it is helpful to think of the yati Kuśalacandrasūri and the sādhu Rājayaśasūri as both scholar-ascetics and money-controlling ritual specialists. Behind every temple-building project, there is not only royal or lay patronage. There are also monks who commission the temples and consecrate their images.9

An overview of the Jain places of worship in Varanasi today highlights how Jains have shifted the focus of worship in the city between two key sites: (1) Bhelūpur, in the center of the city, which is understood as the birthplace of Pārśva and now houses Rājayaśasūri’s impressive temple, and (2) the area of the city known as Maidāgin, north of Varanasi’s main marketplace, Chowk, which houses Kuśalacandrasūri’s temple near Rām Ghāṭ. Both areas flourished as sacred sites for Jains during periods of political stability that brought merchants and scholars to the city. Bhelūpur has been understood as Pārśva’s birthplace since at least the sixteenth century, when Varanasi, under Mughal rule, became a destination for traders and brahmin intellectuals, and the area around Chowk became a center for Jainism in the nineteenth century, when an increasing number of Jain merchants migrated to the city and settled around the main marketplace. To fashion this new settlement as “Jain” in the nineteenth century, Kuśalacandrasūri linked the story of Pārśva saving the snakes to his residence on the Ganges to attempt to transform Rām Ghaṭ, a location that found its original importance as a home for merchants, into an ancient, mythical space belonging to the Jain community.

Kuśalacandrasūri and his disciples’ presence is not felt very much in present day Varanasi, however. Since the death of the last yati to reside at the Rām Ghāṭ temple in 1966, the center of Jain life in Varanasi has slowly shifted back to Bhelūpur, culminating, in part, in Rājayaśasūri’s consecration of the Śvetāmbara temple in 2000. While both Kuśalacandrasūri and Rājayaśasūri have seen the importance of linking Jain literature to temple-building projects to legitimate Jain presence in commercial sites, Kuśalacandrasūri was not able to find any significant, lasting influence. Rājayaśasūri, in establishing a temple not simply for himself and his lineage, but for wandering mendicants from various lineages, has found success with his Bhelūpur temple, reorienting the focus of Jain worship away from the magnificent former home of Kuśalacandrasūri.

1. Jainism in Varanasi

To understand the history of these two Pārśva temples, it will help to first situate them in the larger landscape of religiosity in Varanasi. Today, Hindus and Muslims greatly outnumber Jains in Varanasi. The city is not one of the more popular sites of Jain pilgrimage, nor does it have many Jain residents. In the 2011 Census, from among the almost 3.7 million residents of the district of Varanasi, only 1898 people declared themselves to be Jain.10 On-the-ground approximations correspond remarkably well with the Census’s findings.11 Members of the Jain community estimated to me that about 1600 image-worshipping (mūrtipūjaka) Jains—around 1000 Digambaras and 600 Śvetāmbaras—live in Varanasi today, and there are fewer than 300 lay followers of the anti-iconic sects, Terāpanthin and Sthānakavāsin. However, even though it is not a center of Jain activity, a steady stream of Jain pilgrims still make their way to Varanasi, as the city and surrounding area are said to be to the site of four of the five auspicious events (kalyāṇaka)—conception (cyavana), birth (janma), renunciation (dīkṣā) and enlightenment or omniscience (kevalajñāna)—of four tīrthaṅkaras: Supārśva (7th), Candraprabha (8th), Śreyāṃsa (11th), and Pārśva (23rd).12

Bhelūpur, the supposed birthplace of Pārśva, is the heart of Jain worship in Varanasi today, housing two new, impressive temples of each image-worshipping sect. The main Digambara Pārśva temple at Bhelūpur, which houses the offices of the Digambar Jain Samāj of Varanasi, was founded in 1990 and consecrated in January 2005. The Digambar Jain Samāj of Varanasi maintains six temples throughout the city in which members of both the main divisions of Digambara Jainism, Bīsapanthins and Terāpanthins, worship.13 Bīsapanthins and Terāpanthins disagree on a few components of daily temple worship, including the substances used in the daily ablution (abhiṣeka) of the temple icons (mūrti). While Bīsapanthīs perform an abhiṣeka with five substances (pañcāmṛta)—water, milk, curds, water scented with sandal, and ghee—Terāpanthins perform abhiṣeka with only purified water. Both types of abhiṣeka are performed at all of the Digambara temples run by the Digambar Jain Samāj of Varanasi, however, so some priests to whom I spoke referred to these temples as Digambara “16 ½” temples, adding the Hindi numbers in the names of the two groups, bīs (20) and terā (13) to arrive at 33.33, and then dividing the sum in half to show participation from both groups: 33÷2 = 16 ½.

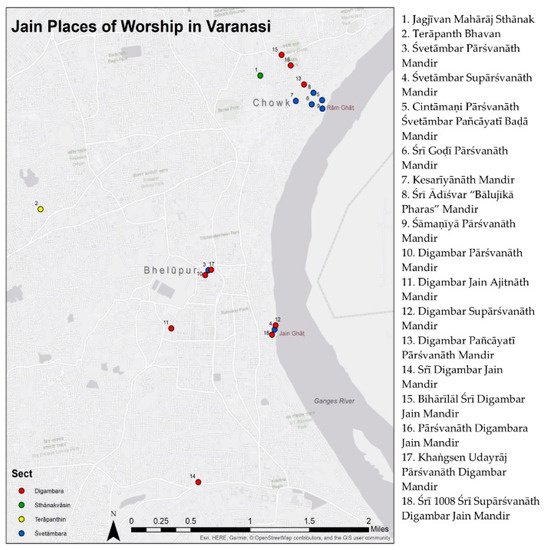

The office of the Śvetāmbara counterpart to the Digambar Jain Samāj, the Śvetāmbar Jain Tīrth Society, is also housed in Bhelūpur, adjacent to the temple that was consecrated in 2000. The Śvetāmbar Jain Tīrth Society maintains five temples in and around Varanasi that were commissioned by monks of two mendicant lineages, the Kharataragaccha and the Tapāgaccha. Medieval Kharataragaccha chroniclers claim that the lineage—now quite small and flourishing primarily in Rajasthan—was established in Patan, Gujarat in the eleventh century to reject the practices of temple-dwelling monks, while Jagaccandrasūri is thought to have founded the Tapāgaccha—the lineage most populous in Gujarat and to which most Śvetāmbara monks belong today—in Chittor, Rajasthan, in the thirteenth century, also in reaction to lax mendicant practices (Dundas 2002, pp. 140–45). The following map (Figure 4) and tables of the better-known Jain places of worship in Varanasi (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4) provide an understanding of the histories, locations, sectarian affiliations, and mythologies associated with places of Jain worship in and around the city.

Figure 4.

Map of Jain places of worship in Varanasi. Created by Megan Slemons at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship.

Table 1.

Sthānakvāsin places of worship in Varanasi.

Table 2.

Śvetāmbara Terāpanthin place of worship in Varanasi.

Table 3.

Śvetāmbara temples in Varanasi.

Table 4.

Digambara temples in Varanasi.23.

These tables show that the economy of Jain worship in Varanasi is dependent upon the city’s link with the four tīrthaṅkaras said to have been born in and around the city, especially Pārśva. Many of the temples receive few regular local visitors, and their budgets thus rely heavily upon pilgrims who come in busloads to visit the four sites associated with Supārśva, Candraprabha, Śreyāṃsa, and Pārśva. In addition, the map shows three clear centers of Jain worship in the city. The three outliers on the map—the places of worship for anti-iconic Terāpanthins and Sthānakavāsins and the only strictly Terāpanthin Digambara temple, the temple to Mahāvīra located outside Banaras Hindu University—were all constructed within the last seventy years to meet sectarian needs. All of the other Jain temples are located in one of three locations: (1) in Bhelūpur in the center of the city, which is understood as the birthplace of Pārśva, (2) in Bhadainī, near what is now known as the Jain Ghāṭ, which is understood as the birthplace of Supārśva, and (3) around Varanasi’s main marketplace, Chowk. Since none of these temples date before the 18th century, this raises a question: How long have Jains understood these locations in and around Varanasi as the sites of events in these tīrthaṅkaras’ lives?

2. Placing Pārśva’s Life in Varanasi Before the Nineteenth Century

To date, most introductions to religion in Varanasi maintain that the city has been a sacred site of Jainism since the middle of the ninth century BCE, when scriptures claim that Pārśva was born in the city (Jain 2006c, p. 18; Eck 1982, p. 57). The historicity of Pārśva is not, however, firmly established, and there is no evidence that he lived in Varanasi,24 so it becomes important to examine Pārśva’s biographies not to gain information about ancient Varanasi, but to understand the time periods when monks composed and developed these stories.25 Jain texts begin to present biographical information about tīrthaṅkaras other than Mahāvīra in the first few centuries CE. 26 One of the earliest lists of the birthplaces of the tīrthaṅkaras is found in the Śvetāmbara Āvaśyakaniryukti, and this text agrees with other Jain accounts—Digambara and Śvetāmbara—that both Pārśva and Supārśva were born in Varanasi (Āvaśyakaniryukti 236/069; 236/7).

Early Jain biographies likely place the lives of Pārśva and Supārśva in Varanasi because the city was an important commercial center of north India in the early centuries of the Common Era.27 Since early Jain biographical accounts of the tīrthaṅkaras were composed in north India around the turn of the first millennium, these texts maintain that many of the tīrthaṅkaras were born in thriving north Indian cities of this time period that play prominent roles in non-Jain texts. Five tīrthaṅkaras were born in Ayodhya, famed capital of Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa, for example, while three were born in Hastinapur, the seat of the kingdom fought for in the Mahābhārata.

These texts composed before the medieval period do not, however, display much familiarity with these cities, and it is not possible to locate all of the cities associated with the lives of the tīrthaṅkaras. For example, the Āvaśyakaniryukti 236/7-8 names Candrānana and Siṃhapura as the birthplaces of Candraprabha and Śreyāṃsa, respectively,28 but these cities may not have been associated with towns around Varanasi until the medieval period.

While a new archeological or textual find could change this hypothesis, for now, it appears that Jains have had a presence in Bhelūpur since the medieval period, they established a presence around the Jain Ghāṭ around the sixteenth century, and they established themselves in Chowk in the nineteenth century. Archeological finds confirm that Jain image worship occurred in Varanasi at least as early as the Gupta Period.29 M.A. Dhaky (1997) has dated a Pārśva icon unearthed at the site of the present day temples in Bhelūpur to the fifth century CE, suggesting that this site could have been understood as his birthplace at this time (Tiwari 2006, pp. 107–8). Other icons have been found at the site that have been dated to the ninth and eleventh centuries (Śivprasād 1991, p. 110).

To provide more evidence that Bhelūpur was understood as the site of Pārśva’s birth in the medieval period, scholars have also cited the Vividhatīrthakalpa (VTK30), the important Sanskrit-and-Prakrit text on Jain pilgrimage sites composed by the Śvetāmbara monk of the Kharataragaccha, Jinaprabhasūri, in 1332. However, while Jinaprabhasūri did visit Varanasi and write about a temple to Pārśva, he is not clear in his text about the location of the tīrthaṅkara’s place of birth. He mentions a Pārśva temple in Varanasi located in the forest near a water tank named Daṇḍakhāta or Daṇḍakhyāta, depending on the manuscript (VTK 38.24), but he does not specify the location of the tank, nor does he say that it is in the location of the tīrthaṅkara’s birth. Jinaprabhasūri also does not mention that there is a temple to Supārśva in Varanasi.

In known sources, a clear consensus that Pārśva was born in Bhelūpur and Supārśva was born near the Jain Ghāṭ did not emerge until the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These centuries marked a period of great stability and scholarly production in the city. Varanasi fell under the direct control of the Mughal Empire between 1574 and 1576, as Akbar consolidated his power throughout north India after his campaign into eastern India in 1574 (Desai 2017, p. 18; Asher and Talbot 2006, pp. 126–27). Increased stability and connections between regions of north India between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries brought to Varanasi a significant number of brahmin intellectuals and ritual specialists from different parts of India (O’Hanlon 2010, pp. 201–4). Merchants, as well, took advantage of Mughal infrastructure, and “[a]t its height before 1720, Moghul rule gave greater security to the long-distance traveler or pilgrim than he had ever before enjoyed” (Bayly 1981, p. 163). Varanasi thrived in this period as a pilgrimage center because it became a popular stop for merchants travelling on the Ganges.31

Perhaps the most famous source on Jain worship in Varanasi comes from one of these merchants, the Digambara Banārsīdās (1586–1643), who undertook a pilgrimage to Varanasi in the first half of the seventeenth century and recorded his experience in his the Braj-bhāṣā autobiography, the Ardhakathānaka, composed in Agra in 1641. Banārsīdās describes his ten-day stay in Varanasi for Kārttika Pūrṇimā, explaining that Jains at this time could draw upon the idea that Pārśva and Supārśva were born in the city in order to make their trip to this holy city a “Jain” pilgrimage. Banārsīdās explains that “the followers of Shiva went to bathe in the Ganga, [while] [t]he Jains went to offer puja to Lord Parshvanath” (v. 231). He himself, then, embodies both traditions:

- Upon reaching the city of Kashi,

- Banarsi first bathed in the Ganga,

- Then offered puja to Parshvanath and Suparshvanath,

- With devotion in his heart (v. 232).

Banārsīdās is said to have offered Supārśva and Pārśva milk, ghee, rice and gram oil, betel, and many kinds of flowers every day for ten days, and it is likely that he visited the Bhadainī and Bhelūpur temples to make these offerings, since in a pilgrimage memoir dated to 1612–13 CE—just a few years after Banārsīdās’s visit—the Digambara poet Yaśakīrti explicitly mentions Bhadainī as the birthplace of Supārśva and Bhelūpur as that of Pārśva (Jain 2006b, p. 100). Additionally, we have even earlier evidence of these temples. The earliest known textual account of a Pārśva temple in Bhelūpur comes from a Digambara manuscript dated to 1562,32 and Supārśva’s birthplace may have been understood as Bhadainī by this time, as well. In an Early Gujarati text praising various pilgrimage spots composed between 1578 and 1620, the Sarvatīrthavandanā, the Digambara monk Jñānasāgara, disciple of Bhaṭṭāraka Śrībhūṣaṇa, praises the temples to Pārśva and Supārśva located along the banks of the Ganges in Varanasi (v. 10 in Joharāpurkar 1965, p. 66). Brahmin intellectuals, then, were not the only religious specialists to move to Varanasi in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. While we have little information about the establishment of the Digambara temples to Pārśva and Supārśva in Varanasi mentioned in these sources, we likely first see mentions of these temples in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries because an increasing number of Digambara mendicants and merchants visited and settled in the city during this period of stable Mughal rule.

Seventeenth-century Varanasi’s status as a center for brahmanical scholarship (Pollock 2001, pp. 8–9) also attracted Śvetāmbaras to the city. The great polymath Śvetāmbara monk Yaśovijaya (born in Gujarat in 1624) stayed from about 1642 to 1654 at a college (maṭha) in Varanasi to study logic (nyāya) with prominent brahmin intellectuals (Jain 2006a; Ganeri 2008), and from this time, we have the earliest known Śvetāmbara source to specifically mention Bhelūpur as Pārśva’s birthplace: a mention by the monk Śrīvijaya in 1654–1655 (Nahata 1995, p. 16). Even earlier, in 1607–8, the Śvetāmbara monk Jiyavijaya referenced temples in Varanasi “at the birthplace[s] of Pārśva and Supārśva” in his account of pilgrimage sites (Jain 2006b, p. 98). Therefore, by the turn of the seventeenth century, Śvetāmbaras and Digambaras had established themselves in the city alongside their brahmin counterparts, and these Jains were able to draw upon early Jain literature to justify their presence in the city.

As for the places just outside of Varanasi associated with the auspicious events in the lives of Candraprabha and Śreyāṃsa, Candrāvatī appears to have been a medieval Śvetāmbara place of pilgrimage, while Siṃhapurī is a more recent development. Jinaprabhasūri in his fourteenth century Vividhatīrthakalpa mentions a temple to Candraprabha in Candrāvatī, which he says is located 2.5 yojanas away from Varanasi proper (VTK 38.28–29). In addition, a copper plate has been found at the site that dates from 1099–1100 and records the donation of land for a Candraprabha temple, confirming this site as a Śvetāmbara place of pilgrimage since at least the twelfth century. Medieval Digambaras, on the other hand, have made no mention of Candrāvatī (Śivprasād 1991, p. 93). Additionally, both medieval Śvetāmbaras and Digambaras make no mention of the birthplace of Śreyāṃsa being located in Sarnath.

Indeed, much of the Jain landscape in and around Varanasi was made in the nineteenth century. Śreyāṃsa’s birthplace was highlighted as Sarnath at this time, the same time that the area around Maidāgin—the Ṭhaṭherī Bāzār area north of the main commercial area of Varanasi, Chowk, or Chaukhambh—began to be understood as a sacred Jain site. Not surprisingly, one of the main impetuses behind the formation of these locations as “Jain” was a monk, the Śvetāmbara temple-dwelling Kuśalacandrasūri we met at the outset of this essay.

3. The Nineteenth-century Kuśalacandrasūri and the Making of a “Jain” Varanasi

Chowk, or Chaukhambha, the market area in north Varanasi, rose to prominence as a mercantile center along the trade route of the Ganges in the eighteenth century, and Jain merchants began to settle there shortly thereafter.33 In 1781, the East India Company took direct control of Varanasi, and just as Mughal rule of the city generated more connectivity for merchants and monks in north India, so too did British rule. Jain merchants benefitted from this connectivity, passing through Varanasi in increasing numbers. By the early nineteenth century, James Tod had reported that Jain merchants—many bankers and jewelers—accounted for half of the total commercial wealth circulating between Rajasthan and Calcutta, and Varanasi was an important stop along the Ganges between these areas of commerce, especially between Delhi and Calcutta (Bayly 2012, p. 141). While Tod’s estimate was likely exaggerated, it is clear that the significant wealth of Jains in Varanasi had a profound influence on the development of the market area of the city around Chowk. The Digambara Jain layman Khub Chand, for example, a Bundelkhandi jewel trader, was a major property owner around Chaukhambha at this time (Bayly 2012, p. 280; Shin 2018, p. 6).

These wealthy Jain merchants—both Digambara and Śvetāmbara—not only developed areas of residence and trade around Chowk, they also established over a dozen places of worship in the area. Today, the steps down to the river near the Supārśva temples are called the “Jain Ghāṭ.” However, as recently as the early twentieth century, Rām Ghāṭ was known as the “Jain Mandir Ghāṭ” because of the predominance of Jain temples in the area. “Jain temples stand above the Jain Mandir Ghat near Panchaganga whose plain white tapering spires uplifted admidst the surrounding elaborate Hindu architecture have a very striking appearance,” the scholar Rajani Ranjan Sen describes in his 1912 account of The Holy City (Benares) (Sen 1912, 58).

For Śvetāmbaras, the temple-dwelling renunciant (yati) Ācārya Kuśalacandrasūri of the Kharataragaccha (initiated in 1778) shaped much of this modern landscape of Jainism around Rām Ghāṭ and throughout Varanasi. Kuśalacandrasūri was well connected to British officials, wealthy lay merchants, and royal patrons. He is the only Jain “fuqueer” in James Prinsep’s Benares Directory (1822), which notes that “numerous Thakoors are embellished with jewels presented by his many rich pupils” (Nair 1999, p. 260; Shin 2015, p. 145). Additionally, the Sanskrit text of 289 verses on the lives of Kuśalacandrasūri and his successors composed by Maṇicandra, a yati in his lineage, in 1951, the Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśasti (SKPP34), describes Kuśalacandrasūri’s connection to the king of Varanasi, Ishwari Narayan Singh (r. 1835–1889). Kuśalacandrasūri is said to have impressed the Sanskrit scholar and preceptor to the king, the sādhu Kāṣṭhajihvā Svāmī,35 warranting an invitation to the king’s court, where he pleased the king so much that he was offered many gifts (SKPP, vv. 42–70).36

Kuśalacandrasūri used these resources to establish or to restore (jīrṇoddhāra) five places of Śvetāmbara worship in and around Varanasi. He renovated and consecrated new images for the Śvetāmbara Supārśva temple near the Jain Ghāṭ, and along with Hīradharmasūri, he re-consecrated an icon of Pārśva’s footprints (pāduka) that had been found under a banyan tree for installation in the previous Śvetāmbara temple at the birthplace of Pārśva in Bhelūpur (SKPP, vv. 86–89; 91–92). These footprints have now been installed in the current Śvetāmbara Bhelūpur temple dedicated to Pārśva.37 In 1835, Kuśalacandrasūri commissioned the current Śvetāmbara temple in Candrāvatī (Candrapurī) that marks the birthplace of Candraprabha (Jain 2013, p. 30), and the temple appears to have been influential enough that Digambaras established their own temple there—perhaps the first Digambara temple in Candrāvatī—in 1913 (Singh and Rana 2002, p. 207). Kuśacandrasūri is also said to have, in 1800, restored a Śvetāmbara temple in Sarnath, which was by that time recognized as Siṃhapurī, the place of the eleventh tīrthaṅkara’s conception, birth, renunciation, and enlightenment in early Jain scriptures (Sinha 2006, pp. 63–64). Just as Banārsīdās recognized that Jains can draw upon their own literature to make a predominantly Śaiva, or “Hindu,” place of pilgrimage “Jain,” Kuśalacandrasūri, in emphasizing that an unknown city in early Jain literature, Siṃhapurī, is Sarnath, attempted to make “Jain” a site more associated with Buddhism, the location of an important Buddhist stūpa and the Buddha’s first teachings. After being mostly ignored for six centuries, attention was again brought to Buddhist Sarnath in 1794 when Jagat Singh, a minister of the king of Varanasi, excavated the Dhameka Stūpa to procure materials for his building projects (Guha-Thakurta 2004, p. 88). To ensure that Sarnath was not solely associated with Buddhism, Kuśalacandrasūri re-established a Jain presence in Sarnath shortly thereafter, in 1800, and as in Chandrāvatī, Digambaras followed, consecrating their current Śreyāṃsa temple located next to the Dhameka Stūpa in 1824 (Sinha 2006, p. 62).

4. Pārśva, the Goddess Padmāvatī, and the Temple at Rām Ghāṭ

The most impressive of Kuśalacandrasūri’s projects, however, was his residence, the Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth Mandir at Rām Ghāṭ, which was established in the Jain neighborhood north of Chowk and consecrated in 1814. In this period, in the early nineteenth century, Varanasi was like many economic hubs, in that advances in infrastructure, relative political stability, and the economic interests of the British brought Jain merchants from different backgrounds together in new environments. John Cort explains:

Communities that had been more geographically distinct in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries now found themselves living side by side in new economic metropoles, such as Bombay, and revived metropoles, such as Ahmedabad, and had to create a shared imagined identity and history.(Cort 2019, p. 106)

In commissioning his Rām Ghāṭ temple, Kuśalacandrasūri created this shared history. The two other main Jain places of worship in Varanasi on the map—Bhelūpur and the Jain Ghāṭ—had already been established as the sites of the conception, birth, renunciation, and enlightenment of Pārśva and Supārśva, but the Jain community was no longer centered around these locations. Therefore, to claim that he located his Pārśva temple on Rām Ghāṭ not simply because of economics, but also because of tradition, Kuśalacandrasūri decided to link this temple with another event in the life of Pārśva that was perfect for Śvetāmbaras to use to reject the predominant brahmanical rituals in Varanasi, promote the ideals of non-violence, highlight the powers of the deities of Jainism, and make the claim for the ancient association of Rām Ghāṭ with Jainism. To this day, priests and devotees affirm that this temple marks the very spot where a young Pārśva saved a pair of snakes from the fires of an immoral brahmin ascetic named Kamaṭha.

There are many different versions of this story of Pārśva and Kamaṭha, but according to M.A. Dhaky, the earliest Śvetāmbara account is found in Ācārya Śīlāṅka’s ninth-century Prakrit history of the universe, the Cauppannamahāpurisacariya (CMC38). Śīlaṅka’s version of the story can be summarized as follows: One day, Pārśva, still a prince in Varanasi, looked down from the terrace of his palace to see the townspeople rushing out of the city with offerings of flowers. Having asked about this commotion, his attendants informed him that the people were going to greet a great ascetic named Kaḍha who had arrived just outside of the city. The young prince thus went to meet the man, approaching the ascetic who was sitting under the blazing sun, surrounded by four fires, performing the austerity of five fires (pañcāgnitapas). As he approached, the prince was distraught to see that Kaḍha was, with the fire for his tapas, burning a snake alive. Though young, Pārśva stood up to the ascetic, telling him to abandon this worthless self-torture that harms living beings. Dharma cannot exist without compassion, Pārśva explained. Having his servants split open the log, the burnt, dying snake was revealed, and the future tīrthaṅkara had the people chant the main Prakrit mantra of Jainism, the pañcanamaskāra-mantra. Through the power of this mantra, upon his death, the serpent was reborn as king of the snake gods (nāga). Kaḍha, on the other hand, because of his sinful practices, was later reborn as the demon Mehamālin (Skt. Meghamālin) (CMC, pp. 261–62). Years later, Meghamālin and the nāga king played a significant role in Pārśva’s attainment of omniscience (kevalajñāna). As Pārśva sat in meditation, nearing enlightenment, the demon Meghamālin attacked the meditating ascetic with rocks, rains, lions, and so on. Eventually, the king of the serpents, Dharaṇa, emerged from the underworld to shield the mendicant with his snake hood, allowing Pārśva to meditate in peace and become omniscient (CMC, pp. 267–68).

Pārśva’s encounter with the immoral ascetic eventually became a staple part of both Digambara and Śvetāmbara textual accounts of Pārśva’s life,39 and the different sects’ versions of the story have changed very little over time.40 Śvetāmbaras consistently claim that only one snake—the serpent who would eventually become Dharaṇendra, king of the nāgas—is saved from the fires of the immoral ascetic. Digambaras, however, name two snakes, who become Dharaṇendra and his queen, Padmāvatī.

These versions of the story do not give specifics about where this encounter between Pārśva and the immoral ascetic occurred. Indeed, Pārśva’s biographies composed before the fourteenth century show no familiarity with Varanasi.41 It was not until the fourteenth century that the story became tied to the city of Varanasi itself. As noted earlier, the Śvetāmbara monk Jinaprabhasūri visited Varanasi, so in his fourteenth century Vividhatīrthakalpa, he could locate Pārśva’s encounter with Kamaṭha in a specific site in the city—Maṇikarṇikā Ghāṭ, what is today the famous cremation ground at the heart of the city (VTK 72.11–14 trans. Chojnacki 1995, p. 251). By this period, Maṇikarṇikā Ghāṭ was known as a center for brahmanical rituals such as bathing, though scholars have debated to what extent it was a site of cremation.42 Jinaprabhasūri’s placement of the Kamaṭha–Pārśva encounter at Maṇikarṇikā suggests, however, that it was linked to cremation at this time. By locating Pārśva’s lecture on the importance of non-violence and compassion at a site synonymous with brahmanical rituals steeped with violence—the burning of logs—Jinaprabhasūri gave his fourteenth-century audience a potent contrast between the teachings of Jainism and brahmanical rituals.

By the nineteenth century, the Jain community had established their neighborhood around the marketplace north of Maṇikarṇikā Ghāṭ, so Kuśalacandrasūri argued for this event’s location on Rām Ghāṭ. He made this argument through three different artistic works in the temple: two different paintings and one shrine. Today, after climbing a flight of stairs and passing through the lecture hall and monastery (upāśraya) with paintings of the monks who once resided in this hall, a visitor to the temple will enter the brightly colored, elaborately painted main shrine of the temple, with the black Pārśva icon consecrated by Kuśalacandrasūri at its center. According to the Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśasti, Kuśalacandrasūri was alerted to the location of this icon, which supposedly dates to the Mughal Period, in a dream, and then purchased it from a layperson for 300 rupees and established it in his temple along the banks of the Ganges (SKPP, vv. 79–81).

In the circumambulation path around this icon, a magnificent watercolor of the life of Pārśva fills the entirety of the backside of the shrine. As Heeryoon Shin (2018) has recently discussed in detail, this mural, which faces out of a temple window towards the Ganges and likely dates to the time of the construction of the temple, depicts the life story of Pārśva as occurring along the banks of nineteenth century Varanasi. In the bottom panel of the painting, the Ganges is depicted as a vibrant location of trade and worship: smaller rowboats, fish, swimmers, and a larger British ship float by dozens of temples established on the ghāṭs frequented by throngs of worshipers. Additionally, in the center of the painting, just above the Ganges, the encounter of prince Pārśva and Kamaṭha is depicted (Figure 5). A green, crowned Pārśva sits on his royal elephant with his wife, surrounded by his royal entourage on elephants and horses. In front of him, his red-turbaned attendant raises an ax above a log from which a single snake head rises. A dark Śaiva ascetic, Kamaṭha, with female onlookers behind him, sits between four fires and observes the scene. While the landscape is predominantly Śaiva, with many liṅga shrines, the painting also depicts the easily recognizable minarets of the seventeenth-century “Aurangzeb’s Mosque” on Pañcagaṅgā Ghāṭ just above Pārśva. This painting thus powerfully critiques the Śaiva practices that were so prevalent in nineteenth-century Varanasi and argues that this event did, indeed, take place precisely at the location of Kuśalacandrasūri’s temple on Rām Ghāṭ, located just one ghāṭ south of Pañcagaṅgā Ghāṭ.

Figure 5.

Detail of the Pārśva-Kamaṭha encounter watercolor on the backside of the main shrine in the Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth Temple at Rām Ghāṭ. Nineteenth century.

According to the priest of the temple, another early nineteenth-century watercolor depicting the Kamaṭha-Pārśva encounter covered the north wall of the lower-level shrine room until about 20 years ago. The painting surrounded a small shrine dedicated to the tutelary goddess (śāsanadevī) of Pārśva, Padmāvatī, which designates the exact spot where the event is said to have taken place. This shrine—marked as Kamaṭh Pratibodhitasmārak Sthal, “Memorial of the Site Where Kamaṭha was Instructed”—contains an icon of the snake goddess Padmāvatī, flanked on each side by a fly-whisk bearer, and established beneath a slightly smaller Pārśva icon seated on a throne (Figure 1). An inscription below the shrine notes that it belongs to the Kharataragaccha and was consecrated in 1816–17, about two years after the consecration of the temple.

This shrine to Padmāvatī should be considered to be an innovative retelling of the Śvetāmbara story of the Pārśva-Kamaṭha encounter. Kuśalacandrasūri not only relocated the event from previous tellings, he also added Padmāvatī, a powerful goddess, to the Śvetāmbara version of the story. Scholars have conjectured that this goddess was initially a kuladevī, or a family goddess, of a series of important royal families in Karnataka such as the Śīlahāras, Raṭṭas, and Śāntaras (Cort 1987, p. 243; Desai 1957, p. 171). Due to the families’ adherence to Digambara Jainism, she was eventually incorporated into the Digambara Jain pantheon, becoming the female attendant (śāsanadevī or yakṣī) of Pārśva around the late ninth, or early tenth centuries, which explains her inclusion in the earliest Digambara versions of the Kamaṭha encounter that developed in this period (Shah 1959, pp. 141–43). By at least the eleventh century, however, Śvetāmbaras, too, had accepted Padmāvatī as Pārśva’s yakṣī,43 and she is now undoubtedly one of the most popular goddesses of both image-worshipping Jain sects, with hundreds of stories promoting her powers to save devotees from everything from serious illness to poverty. Therefore, to draw devotees wanting health and wealth to the temple, Kuśalacandrasūri chose this goddess to become the main symbol of the event at the Rām Ghāṭ temple, despite her absence from Śvetāmbara versions of the tale.

5. Understanding Kuśalacandrasūri and His Disciples as Erudite Ascetics

Kuśalacandrasūri and his immediate disciples were not the only yatis to reside in this temple, however. Subsequent Kharataragaccha temple-dwelling mendicant leaders (ācārya) in Kuśalacandrasūri’s Diṅmaṇḍalācārya branch of the mendicant lineage the Kharataragaccha also contributed to the development of Jainism in Varanasi: Bālacandrasūri (established as ācārya in 1883), Nemicandrasūri (established as ācārya in 1906), and Hīrācandrasūri (established as ācārya in 1943, died in 1966) (Vinayasāgara 2004, pp. 325–26).

Temple-dwelling yatis like these men have been characterized as “quasi-renunciant ritual specialists (yati) with scant familiarity with traditional Sanskrit and Prākrit learning” (Dundas 2007, p. 171). However, while many yatis might rightly be characterized in this way,44 these yatis of Varanasi were not simply ritual specialists along the lines of the Śvetāmbara temple priest who today maintains the temple. This priest, a non-Jain married brahmin, is responsible for the daily worship of the hundreds of images established in the temple—including 96 tīrthaṅkara icons (pratimā) (Surānā et al. 2004, p. 23). He performs a ritual ablution (abhiṣeka) of the main image of each shrine every morning, offering flowers and lamps to key shrines, and dotting the temple images with sandalwood paste. He has been hired by the Śvetāmbar Tīrth Society to do so, because once a temple image has been consecrated, it must be worshiped every day, and there are few regular Jain visitors to this temple. This man, then, might be understood as simply a ritualist, since he is not celibate, has not taken any of the vows of Jain mendicancy, and he does not have detailed knowledge of Jain scripture and doctrine.

The texts and representations of Kuśalacandrasūri and his yati predecessors displayed at the upāśraya at the Rām Ghāṭ temple, however, suggest that these men were much more like medieval and modern peripatetic Śvetāmbara monks than they were like this temple priest. Indeed, these yatis embody many elements of Jain asceticism as defined in early and medieval scriptures. The classical Sanskrit text on the path to liberation accepted by both Digambaras and Śvetāmbaras, the Tattvārthasūtra (ca. fourth century CE), contains a definition of asceticism (tapas) that lists twelve acts (TS 9.19–20): fasting, limiting one’s food, restricting what one eats, abstaining from delicious food, sleeping alone, avoiding temptation, expiation, respecting mendicants, serving mendicants, study, meditation, and ignoring the desires of the body (Cort 2001, p. 120). For the lineage of the monks who lived at Rām Ghāṭ —the Kharataragaccha—the sourcebook for mendicant life, Jinaprabhasūri’s Prakrit-and-Sanskrit text the Vidhimārgaprapā composed in 1306, provides more details about what constitutes asceticism for Jain mendicants. According to this text, to renounce the world (pravrajyā) and to be ordained as a monk (to undertake upasthāpanā), a disciple should be gifted the insignia of a mendicant (the broom and so forth), have his hair pulled out, don the white robes of a mendicant, receive a new mendicant name (VMP45, pp. 34–35), and adopt the five mendicant vows: (1) nonviolence, (2) telling the truth, (3) not taking what is not given, (4) celibacy and (5) non-possession (VMP, p. 38). To become a mendicant leader (ācārya, sūri), then, one must have completed the systematic study of all of the Śvetāmbara canonical texts (yogavidhi). After completing this study and years of mendicancy, the monk can be promoted to the rank of ācārya by having his guru whisper in his ear a Prakrit mantra, the sūrimantra, and receiving a sthāpanācārya, a tripod of wooden sticks that holds a bundle of shells that symbolizes the mendicants who have come before them (VMP, p. 67, lines 8–9; 26).46

While the yatis of Varanasi did not uphold the fifth vow of non-possession and we cannot know whether or not they completed the required scriptural study to become ācāryas, the texts and images associated with them suggest that they undertook the acts of asceticism outlined in the Tattvārthasūtra and were quite learned, following many of the prescriptions of the Vidhimārgaprapā. In the painting of Kuśalacandrasūri seated in his Rām Ghāṭ temple that is now established in a shrine at the temple (Figure 2), he has the markings of many of these ascetic practices. He looks like a Śvetāmbara mendicant: he wears simple white robes, holds a mouth-cloth (muḥpatti) and a mendicant broom (rajoharaṇa) used to reduce his harm to living beings, and has a bald head, signifying that he followed the mendicant requirement of the regular pulling out of one’s hair to reject one’s body. These markings align with the description of Kuśalacandrasūri in the Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśasti, which describes him as performing many austerities on the banks of the Ganges (SKPP, v. 33). He also makes a gesture of teaching in the painting, which aligns with the Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśasti’s consistent descriptions of him as a learned teacher (pāṭhaka), capable, for example, of thoroughly impressing the sādhu Kāṣṭhajihvā Svāmī, scholar-advisor of the king of Varanasi. Additionally, while the painting does not explicitly show any signs of his status as a mendicant leader (ācārya), his biography in the Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśasti confirms that he was always reciting the “King of Mantras,” the sūrimantra, meaning that he was promoted to the rank of mendicant leader following at least some of the prescriptions in the Vidhimārgaprapā (SKPP, v. 6).

The next two ācāryas to reside at Rām Ghāṭ—Bālacandrasūri and Nemicandrasūri— should also be understood as a continuation of the mendicant lineage of the Kharataragaccha, even if they are presented as a bit more worldly than Kuśalacandrasūri (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Their well-groomed hair—especially Bālacandrasūri’s moustache—shows that they were not required to regularly pull out their hair, and they both wear a blue shawl ornamented with a red and gold border, 47 something not found on modern peripatetic mendicants, who have vowed to avoid decorated and colored clothes (Deo 1956, pp. 259–60). Even so, both their paintings mark their statuses as initiated mendicants. A mendicant broom is placed in front of these men, and they both hold in their left hands a mouth-cloth. To the left of each of these men sits a symbol of their status as a mendicant leader (ācārya): a sthāpanācārya. Additionally, while Nemicandra’s shawl might suggest opulence, the Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśasti confirms his austere lifestyle. It emphasizes that Nemicandrasūri, throughout his whole life, never once wore newly made clothes (SKPP v. 195). There is a reason, then, why the two paintings of these ācāryas look so similar: Nemicandrasūri must be wearing his guru’s shawl.

Figure 6.

A painting of Ācārya Bālacandrasūri hung in the upāśraya of the Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth Temple at Rām Ghāṭ. Twentieth century.

Figure 7.

A painting of Ācārya Nemicandrasūri hung in the upāśraya of the Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth Temple at Rām Ghāṭ. Twentieth century.

In addition, even if they may not have followed the systematic study of the Śvetāmbara canon that the Vidhimārgaprapā requires in order to become an ācārya, both monks are described as following the ascetic practice of study (svādhyāya). They are described as being quite learned in Jain doctrine and practice, and Bālacandrasūri even composed a Hindi commentary (vṛtti) on an early-modern Hindi text on Jainism by Kāṣṭhajihvā Svāmī. While a detailed examination of this text must be left for a future publication, for now it is enough to note that in this text, Bālacandrasūri exhibits a good deal of creativity and a deep understanding of several aspects of Jain doctrine and practice, outlining, for example, different types of meditation (dhyāna) and arguing that the syllable oṃ represents the fourteen ritual implements (upakaraṇa) of a Jain mendicant (Maṇicandra 1951, p. 55). Bālacandrasūri was also responsible for organizing a conference of yatis in 1906 that looked to reform and codify the practices of yatis, creating a directory of yatis, systematizing study, and reforming conduct by banning, for example, the sale of manuscripts (Nāhṭā 1982, p. 78).

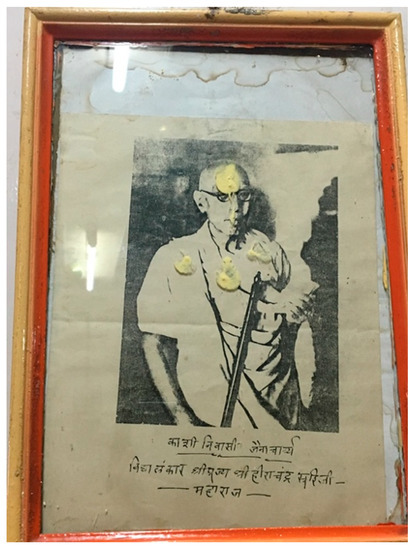

The last ācārya to reside in the Rām Ghāṭ temple, Hīrācandrasūri (d. 1966), was also understood as a celibate ascetic and a scholar of Sanskrit. In his photograph, he wears the simple white robe of a Śvetāmbara monk, he has a bald head, and he holds two insignia of a mendicant: a staff (daṇda) in his right hand,48 and mouth-cloth in his left (Figure 8). The photo also names Hīrācandrasūri as Vidyālaṅkara, or “ornamented in knowledge,” because he was awarded this honorary title by Kāśī Vidvat Pariṣad, an esteemed organization of Varanasi’s Sanskrit scholars (SKPP, v. 263). Hīrācandrasūri’s yati disciple, Maṇicandra, was also well-versed in Sanskrit, since in 1951, he chose to compose the Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśasti, his text on the life of Kuśalacandrasūri and his successors, in Sanskrit, creatively integrating English and Hindi words like “station” and “rupee” into his account. While Maṇicandra’s idealized accounts of the yatis in his lineage should be taken with a grain of salt and Bālacandrasūri’s conference to reform yati practice suggests lax conduct, it does appear that these temple-dwelling renunciants saw themselves as exemplars of the performance of tapas as outlined in the Tattvārthasūtra and upholders of the mendicant tradition of the Kharataragaccha as outlined in texts such as the Vidhimārgaprapā. Today, scholars are not allowed access to the manuscripts housed at the temple at Rām Ghāṭ, but a future study of these texts would surely shed more light on the intellectual lives of these monks.

Figure 8.

Copy of a photograph of Ācārya Hīrācandrasūri displayed and worshiped in the upāśraya of the Cintāmaṇi Pārśvanāth Temple at Rām Ghāṭ. Twentieth century.

In addition, the art and architecture commissioned by these monks should also be taken seriously as part of this intellectual life. The shrine to Padmāvatī at Rām Ghāṭ, for example, should be understood as one of Kuśalacandrasūri’s intellectual projects, since it reimagines the encounter of Pārśva and Kamaṭha as occurring near the flourishing nineteenth century marketplace of Varanasi and involves Padmāvatī, the goddess who otherwise features only in Digambara tellings of the story. Unfortunately, however, Kuśalacandrasūri’s lineage’s attempt at establishing this temple as an important site of Jain worship and learning was ultimately a failed enterprise.

6. The Decline of Rām Ghāṭ and Rājayaśasūri’s Restoration of Bhelūpur

These days, like many of the Jain temples of Varanasi—especially those around Chowk—Kuśalacandrasūri’s temple is almost completely ignored by practitioners. According to one local source, about 75% of the Jain families who once owned homes in Maidāgin, north of the main marketplace, have now left the area, relocating mostly to Bhelūpur. Only about 30–40 Digambara families and a handful of Śvetāmbara families still live in Maidāgin, and only three or four Jains regularly worship at this temple. Most egregiously, there was so little interest in this temple that no effort was made to restore the 200-year-old wall painting of the Kamaṭha-Pārśva encounter on the lower level of the temple. Instead, about twenty years ago, it was whitewashed and replaced with an unimpressive, much smaller depiction of the event. As we can see in Figure 1, this new painting depicts the prince Pārśva leaning respectfully towards Kamaṭha, having dismounted the horse he was riding with his wife. We see Kamaṭha seated between five fires, since the artist did not understand that he should be seated between four fires, as the sun is the fifth fire in a pañcāgnitapas. We can also see two snakeheads popping out of the fire between Pārśva and Kamaṭha, indicating the acceptance of the idea that both Padmāvatī and Dharaṇendra emerged from the fire.

The whitewashing of the original painting of this scene, along with the languishing of the manuscripts housed at this temple, are two of the real losses that arose because of the failure of Kuśalacandrasūri and his temple-dwelling mendicant successors to attract worshipers by relocating this event in Pārśva’s life in the minds of Jain practitioners. While the Pārśva-Kamaṭha encounter is a well-known story, no Jain unconnected to the Rām Ghāṭ temple to whom I have spoken, even in Varanasi, has located the event on Rām Ghāṭ.

Instead, Jains continue to reimagine this encounter in different places to make a variety of arguments. One watercolor painting on a wall of the Digambara Śreyāṃsa temple in Sarnath, for example, locates the event near the ghāṭ that is today most famous for brahmanical practices: Daśāśvamedh Ghāṭ, the site of brahmins’ nightly lamp offering (ārati) to the river Ganges (Figure 9). According to the temple’s priest, the painting was created in 1900 by Chedilal Prajapati, a local resident (Sinha 2006, p. 63). Prajapati was likely not aware of nineteenth-century Śvetāmbaras’ association of the event with Rām Ghāṭ, so he located this encounter in an iconic location in the heart of the modern city. In its depiction of Pārśva standing just south of the modern Daśāśvamedh Ghāṭ, holding the two dying snakes in his hands and preaching to Kamaṭha, this painting allows present day worshipers to feel personally connected to their omniscient teachers. It also, however, illustrates the failure of Kuśalacandrasūri and his followers to establish, once-and-for-all, that this event occurred on Rām Ghāṭ.

Figure 9.

A painting of Pārśva’s instruction of Kamaṭha in the Śreyāṃsanāth Digambar Mandir, Sarnath. Twentieth century.

With the twentieth-century shift of Jain laypeople out from the crowded lanes near Rām Ghāṭ and into homes in the more open Bhelūpur, both Digambara and Śvetāmbara Jains in the 1990s were smart to begin construction on new large temple complexes in Bhelūpur, complete with offices for their organizing committees and large guest houses with food facilities. For Śvetāmbaras, this temple-building project was inspired by the wandering Tapāgaccha monk Rājayaśasūri (b. 1945), who is in many ways quite similar to the Kharataragaccha temple-dwelling monks of Varanasi. The statue of him in Figure 2, for example, depicts the monk in a comparable manner to Hīrācandrasūri, with a mendicant’s staff, a bald head, white robes, and a mouth-cloth. Rājayaśasūri has also used Jain narratives to justify the construction of several temples, most of which look a lot like the Pārśva temple in Bhelūpur, since they use the Māru-Gurjara (Solaṅkī) architectural style to harken back to the so-called “Golden Age” of Jain temple-building in medieval Gujarat (Hegewald 2015). While he does not handle money, as yatis were allowed, he can still be understood as a project manager of sorts. In 2016, laypeople established a public charitable trust in his name, the Shree Rajyashsuri Ashok Kar Trust, and he has been able to garner funds from Jain communities throughout India. He has commissioned two Solaṅkī-style temples and a guesthouse in Bharuch, Gujarat, 49 at the supposed site of the Preaching Assembly (samavasaraṇa) of the twentieth tīrthaṅkara Munisuvrata, 50 where construction is still occurring (Figure 10). He has inspired the renovation of Kulpakjī Tīrth, the largest Jain temple in Telangana, bringing a massive Solaṅkī-style marble temple to South India that holds an icon of Ṛṣabha that was supposedly consecrated by his son, Bharata, but then was obtained by the demon Rāvaṇa and taken to Sri Lanka (for a photo of the temple’s interior, see Hegewald 2015, p. 128).51 He has also commissioned an impressive temple complex in Nagpur, Maharashtra, the Śrī Uvasaggaharaṃ Pārśva Tīrth, at a place where Pārśva is said to have visited,52 and another massive temple 45 kilometers from the pilgrimage site Śatruñjaya, in Gujarat: Mahendrapuram.53

Figure 10.

The remains of a house being torn down for the construction of a Śvetāmbara temple in the Śrīmāḷī Pōḷ in Bharuch, Gujarat. July 2016.

The reactions of monks from competing Śvetāmbara mendicant lineages to Rājayaśasūri’s temple-building projects show how important it can be for a monk to establish trusts and temples in valuable pilgrimage sites to attract pilgrims’ money for their lineages. In 2017, Ācārya Kīrtiyaśasūri (b. 1951), a monk from another branch of the Tapāgaccha—the lineage of Rāmacandrasūri—claimed that because there was a defect in the Pārśva temple in Bhelūpur in Varanasi, he would have to consecrate another temple on the site. This of course prompted a response by Rājayaśasūri, who took to Twitter and YouTube to confirm that the trust established for the Bhelūpur temple dictates that no change can be made to the temple without the permission of Rājayaśasūri and his followers,54 so there will be no new temple constructed at the site of Pārśva’s birth.55

Ultimately, this debate between monks over power over this site shows Rājayaśasūri’s success in returning the center of Jain temple worship in Varanasi back to Bhelūpur. Rājayaśasūri’s project in Varanasi, however, is just one of the many ways in which he has drawn upon scripture and the wealth of the lay community to establish his mendicant lineage’s presence in important places of pilgrimage. While Kuśalacandrasūri spent his whole life in Varanasi and could focus on developing the sacred landscape of that city, Rājayaśasūri and his disciples are always on the move, so they need to establish temple complexes throughout India as places for them to stay.

7. Concluding Remarks

This study of the history of the places of Jain worship in Varanasi has examined a few of the reasons why some temples emerge as important sites of worship and pilgrimage while others remain lost to history. Though scholars often focus on the importance of royal patronage in the emergence of prominent temple complexes, for Jains in Varanasi—an important commercial site along the trade route of the Ganges—kings were not directly responsible for the construction of their temples. Instead, the stability brought by certain rulers—first the Guptas, then the Mughals, then the British—brought the money of lay merchants to the city, and with these merchants came monks, who drew upon scripture and the biographies of the tīrthaṅkaras to legitimize their presence in the city.

In a narrative of an eleventh-century debate between the Śvetāmbara teacher Sūra and the Kharataragaccha monk Jineśvara on the role of temple-dwelling monks, Sūra stresses the necessity of these monks for the flourishing of temple sites. Sūra is said to have argued:

- There would be a lack of temples today if monks did not live in them.

- Previously lay people took great care and interest in temples, teachers and the

- doctrine, but now because of the corrupt age they are so preoccupied with

- providing for their families, they scarcely go to their homes, let alone to the

- temple. The king’s servants also because of their worldly interests no longer

- concern themselves with the temple. Eventually, the Jain religion will be

- destroyed. Ascetics by living in temples preserve them. There is scriptural

- authority for adopting an exception to a general rule to prevent the doctrine

- falling into abeyance.56

A thousand years later, in Varanasi, his warning has proven to be true in the case of one temple and false in the case of another. It is true that since the death of Hīrācandrasūri, the last temple-dwelling ācārya of Kuśalacandrasūri’s mendicant lineage, in 1966, the magnificent temple to Pārśva on the banks of the Ganges at Rām Ghāṭ has become mostly forgotten, with few worshippers visiting to appreciate its art and no scholars allowed to read its manuscripts. On the other hand, in the case of the Śvetāmbara temple commissioned by the saṃvegī sādhu Rājayaśasūri at Pārśva’s supposed birthplace in Bhelūpur, Sūra’s warnings of the demise of Jain temples without temple-dwelling monks have not proved prescient, with the success of the temple so well established that monks of competing lineages are jostling for power over the site. In the end, the eleventh-century Sūra’s argument that the demise of caityavāsins will signal the fall of temples proved false, because saṃvegīs are just as involved in temple building and maintenance as their temple-dwelling predecessors.

In fact, it might be the case that Kuśalacandrasūri’s temple on Rām Ghāṭ did not become famous and widely known as the site of the Pārśva–Kamaṭha encounter precisely because he and his successors lived in the temple. The modern Pārśva temple in Bhelūpur houses Śvetāmbara image-worshipping monks and nuns from all mendicant lineages as they travel throughout India, making it well known to a large section of the Jain community. Kuśalacandrasūri’s project, however, remained a local endeavor of a particular branch of a minority mendicant lineage. After the reforms in the nineteenth century, the number of peripatetic monks and nuns has steadily increased, and these mendicants continue to commission from laypeople an increasing number of temples throughout the subcontinent as both their lodgings and as projects that attract funds to their lineages. If future commissioners of these temples wish to take any lessons from the temple-building projects in Varanasi, then they should be sure to link their temples to commercial sites and welcome wandering mendicants from all lineages to reside at their temples.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Shashank Srivastava for help with initial fieldwork in 2005–2006 and follow-ups in 2009. Thanks to Ranjana Sheel for her support, and thanks also to the anonymous readers for their helpful feedback. The final stage of this project was developed for a presentation at Yale University in 2015 with Heeryoon Shin. Her research related to the project has been published as Shin (2018).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Ardhakathanak (A Half Story). Translated into English by Rohini Chowdhury. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2009.Āvaśyaka Niryukti, Khaṇḍa 1. Edited by Samaṇī Susumaprajñā. Ladnun: Jain Viśvabhāratī Saṃsthān, 2001.Pārśvanātha Caritam of Bhaṭṭāraka Sakalakīrti. Translated into Hindi and edited by Pannālāl Jain. Jaipur: Bhāratavarṣīya Anekānt Vidvat Pariṣad, n.d.Pārśvanātha Caritra of Bhāvadevasūri. Translated by Maurice Bloomfield as The Life and Stories of the Jaina Savior Pārśvanātha. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press. 1919.Pāsanāhacariu of Padmakīrti. 1965. Introduction, Hindi Translation, Index and Notes by Prafulla Kumar Modi. Varanasi: Prakrit Text Society.TS = Tattvārtha Sūtra: That Which Is. Translated into English by Nathmal Tatia. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1994.Triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣacaritra of Hemacandra. Translated into English by Helen Johnson as The Lives of Sixty-three Illustrious Persons. Vol. V. Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1962.Secondary Sources

- Asher, Catherine B., and Cynthia Talbot. 2006. India Before Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Babb, Lawrence A., John E. Cort, and Michael W. Meister. 2008. Desert Temples: Sacred Centers of Rajasthan in Historical, Art-Historical and Social Contexts. Jaipur: Rawat Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, Hans. 1996. Construction and Reconstruction of Sacred Space in Varanasi. Numen 43: 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbir, Nalini. 2000. Le bâton monastique jaina: functions, symbolisme, controversies. In Vividharatnakaraṇḍaka. Festgabe für Adelheid Mette. Edited by Christine Chojnacki, Jens-Uwe Hartmann and Volker M. Tschannerl. Swisttal-Odendorf: Indica et Tibetica Verlag, pp. 17–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bayly, Christopher A. 1981. From Ritual to Ceremony: Death Ritual and Society in North India since 1600. In Mirrors of Mortality: Studies in the Social History of Death. Edited by Joachim Whaley. London: Europa Publications, pp. 154–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bayly, Christopher A. 2012. Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion 1770–1870. Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, Bansidhar. 2009. Is Pārśva the Twenty-Third Jina a Legendary Figure? A Critical Survey of Early Jain Sources (Abstract). Jaina Studies: Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies 6: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield, Maurice. 1919. The Life and Stories of the Jaina Savior Pārśvanātha. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bollée, Willem. 2007. A Note on the Pāsa Tradition in the Universal History of the Digambaras and Śvetāmbaras. International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 3: 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacki, Christine, ed. 1995. Vividhatīrthakalpaḥ: Regards sur le lieu saint Jaina. Volume I: Traduction et Commentaire. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondicherry and École Française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Cort, John. 1987. Medieval Jaina Goddess Traditions. Numen 34: 235–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cort, John E. 1991. The Śvetāmbar Mūrtipūjak Jain Mendicant. Man 26: 651–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cort, John E. 2001. Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cort, John E. 2010. In Defense of Icons in Three Languages: The Iconophilic Writings of Yaśovijaya. International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 6: 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cort, John E. 2019. Jain Identity and the Public Sphere in Nineteenth-Century India. In Religious Interactions in Modern India. Edited by Martin Fuchs and Vasudha Dalmia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 99–137. [Google Scholar]

- Dalmia, Vasudha. 1997. The Nationalization of Hindu Traditions: Bhāratendu Hariśchandra and Nineteenth-century Banaras. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, Shantaram Bhalchandra. 1956. History of Jaina Monachism from Inscriptions and Literature. Poona: Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, Madhuri. 2017. Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, P. B. 1957. Jainism in South India and Some Jaina Inscriptions. Sholapur: Jaina Saṃskṛti Saṃrakṣak Saṃgh. [Google Scholar]

- Detige, Tillo. 2019a. ‘Tataḥ Śrī-Gurus-Tasmai Sūrimantraṃ Dadyāt’, ‘Then the Venerable Guru Ought to Give Him the Sūrimantra’: Early Modern Digambara Jaina Bhaṭṭāraka Consecrations. Religions 10: 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detige, Tillo. 2019b. “Guṇa kahụṃ śrī guru”: Bhaṭṭāraka Gītas and the Early Modern Digambara Jaina Saṅgha”. In Early Modern India: Literature and Images, Texts and Languages. Edited by Maya Burger and Nadia Cattoni. Heidelberg: CrossAsia-eBooks, pp. 271–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaky, Madhusudan A. 1997. “Arhat Pārśva and Dharaṇendra Nexus: An Introductory Estimation”. In Arhat Pārśva and Dharaṇendra Nexus. Edited by M. A. Dhaky. Delhi: Bhogilal Leharchand Institute of Indology, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dundas, Paul. 1987–1988. The Tenth Wonder: Domestication and Reform in Medieval Śvetāmbara Jainism. Indologica Taurinesia 14: 181–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dundas, Paul. 2002. The Jains. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dundas, Paul. 2007. History, Scripture and Controversy in a Medieval Jain Sect. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dundas, Paul. 2008. The Uses of Narrative: Jineśvara Sūri’s Kathākoṣaprakaraṇa as Polemical Text. In Jaina Studies: Papers of the 12th World Sanskrit Conference. Edited by Collette Caillat and Nalini Balbir. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, vol. 9, pp. 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dundas, Paul. 2009. How not to Install an image of the Jina: An Early Anti-Paurnamīka Diatribe. International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 5: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, Diana. 1982. Banaras: City of Light. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Flügel, Peter. 2006. Demographic Trends in Jaina Monasticism. In Studies in Jain History and Culture. Edited by Peter Flügel. London: Routledge, pp. 311–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ganeri, Jonardon. 2008. Worlds in Conflict: The Cosmopolitan Vision of Yaśovijaya Gaṇi. International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 4: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Goḷvāḷā, Mahendra, and comp. 1996. Bhāratnā Mukhya Jain Tīrtho. Ahmedabad: Śrī Mahāvīr Śruti Maṃḍaḷ. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, Ellen. 2017. The Digambara Sūrimantra and the Tantricization of Jain Image Consecration. In Consecration Rituals in South Asia. Edited by István Keul. Leiden: Brill, pp. 265–308. [Google Scholar]

- Guha-Thakurta, Tapati. 2004. Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Postcolonial India. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hegewald, Julia A. B. 2015. The International Jaina Style? Māru Gurjara Temples Under the Solaṅkīs, throughout India and in the Diaspora. Ars Orientalis 45: 115–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Balbhadra. 1974. Bhāratke Digambar Jain Tīrth, Pratham Bhāg. Bombay: Bhāratīya Digambar Jain Tīrthkṣetra Committee. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Bijoy Kumar. 2013. Vārāṇasī ke Jain Tīrth (Jain Pilgrimages of Varanasi). Varanasi: Vijay Kumar Jain ‘Parshwakunj. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, K. K. 2006a. Kāśī, Yaśovijaya and Jaina Institutes. In Jaina Contributions to Varanasi. Edited by R. C. Sharma and Pranati Ghosal. Varanasi: Jñāna-Pravāha Centre for Cultural Studies and Research, pp. 133–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Munni Pushpa. 2006b. Ancient Jaina Culture and Scattered Rare Images of Varanasi. In Jaina Contributions to Varanasi. Edited by R. C. Sharma and Pranati Ghosal. Varanasi: Jñāna-Pravāha Centre for Cultural Studies and Research, pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, Sagarmal. 2006c. Kāśī in Jaina Tradition. In Jaina Contributions to Varanasi. Edited by R. C. Sharma and Pranati Ghosal. Varanasi: Jñāna-Pravāha Centre for Cultural Studies and Research, pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Joharāpurkar, Vidyādhar, ed. 1965. Tīrthavandanasaṃgraha. Sholapur: Jain Saṃskriti Saṃrakṣak Saṃgh. [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw, James. 1995. Riches and Renunciation: Religion, Economy, and Society among the Jains. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maṇicandra, Paṇḍita. 1951. Śrīkuśalacandrasūripaṭṭapraśastiḥ. Kāśī: Jainmandir, Rāmghāṭ. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, Prafulla Kumar, ed. 1965. Pāsanāhacariu of Padmakīrti. Varanasi: Prakrit Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Nāhṭā, Agarcand. 1982. Jain Yati Paramparā. In Karmyogī Śrī Kesarīmaljī Surāṇā Abhinandan Granth. pp. 71–78. Available online: https://jainelibrary.org/book-detail/?srno=210838 (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Nahata, Bhavanlal. 1995. Vārāṇasī: Jaina Tīrtha. Kolkata: Jain Saṃskṛti Kalā Mandir. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, Thankappan P. 1999. James Prinsep: Life and Work. Calcutta: Firma KLM. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hanlon, Rosalind. 2010. Letters Home: Banaras pandits and the Maratha regions in early modern India. Modern Asian Studies 44: 201–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Sheldon. 2001. New intellectuals in seventeenth-century India. The Indian Economic and Social History Review 38: 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Rajani Ranjan. 1912. The Holy City (Benares). Chittagong: M.R. Sen. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Umakant P. 1959. Introduction of Śāsanadevatās in Jaina Worship. Proceedings and Transactions of the All-India Oriental Conference 25: 141–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Umakant P. 1987. Jaina-Rūpa-Maṇḍana. New Delhi: Abhinav. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Umakant P. 1997. The Historical Origin and Ontological Interpretation of Arhat Pārśva’s Association with Dharaṇendra. In Arhat Pārśva and Dharaṇendra Nexus. Edited by M. A. Dhaky. Delhi: Bhogilal Leharchand Institutue of Indology, pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Heeryoon. 2015. Building a ‘Modern’ Temple Town: Architecture and Patronage in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Banaras. Ph.D. thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Heeryoon. 2018. Painting the Town Jain: Reimagining Sacred Space in Nineteenth-Century Banaras. Artibus Asiae 78: 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Rana P. B., and Ravin S. Rana. 2002. Banaras Region: A Spiritual and Cultural Guide. Varanasi: Indica Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, S. S. 2006. Significance of Sarnath in Jaina Tradition. In Jaina Contribution to Varanasi. Edited by R. C. Sharma and Pranati Ghosal. Varanasi: Jñāna-Pravāha Centre for Cultural Studies and Research, pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Śivprasād. 1991. Jain Tīrthoṃ kā Aitihāsik Adhyayan. Varanasi: Pāśvanāth Vidyāśram Śodh Saṃsthān. [Google Scholar]

- Surānā, Śrīcand "Saras", Rājeś Surānā, and Sanjay Surānā, eds. 2004. Jain Tīrth Paricāyikā. Agra: Divākar Ṭaiksṭogrāphiks. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, Maruti Nandan Prasad. 2006. Jaina Sculptural Art of Kāśi. In Jaina Contribution to Varanasi. Edited by R. C. Sharma and Pranati Ghosal. Varanasi: Jñāna-Pravāha Centre for Cultural Studies and Research, pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Vinayasāgara, Mahopādhyāya. 2004. Kharatargacch kā Bṛhad Itihās. Jaipur: Prākṛt Bhāratī Akādamī. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Anand A. 1998. Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For this article, I will transcribe the Hindi for “Jain” and the names of temples and specific places in Varanasi (including the word ghāṭ). I will use the most common English transcription for people who are not monks and more commonly-known place names (e.g., Chowk, Varanasi, Gujarat). I will transcribe the Sanskrit for all other terms, including the names of monks and tīrthaṅkaras. |

| 2 | Jainam Jayati Shasa Nam, 200 Glorious Years of Temple, EventViva. Available online: https://eventviva.com/event/179762095464290 (accessed on 1 May 2014). |

| 3 | On Kuśalacandrasūri and his disciples, see Vinayasāgara (2004, pp. 324–26). |

| 4 | On the Māru-Gurjara (Solaṅkī) architecture, which developed in Gujarat and Rajasthan between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, see Hegewald (2015, p. 136). |

| 5 | Debashish Mukerji & Ajay Uprety. Making of the mandir. The Week, June 7, 1998. Available online: https://www.theweek.in/theweek/cover/ayodhya-temple-construction.html (accessed on 6 January 2020). |

| 6 | For the months of March to June 2009, the Śvetāmbara register in the dharmaśālā’s office in Bhelūpur recorded 1352 pilgrims who stayed at least one night in one of their 40 rooms during this same period. According to the record-keepers in these offices, these numbers double in the winter months. |

| 7 | There were only a couple dozen itinerant Śvetāmbara mendicants in the nineteenth century (Flügel 2006, pp. 319–20). |

| 8 | By the sixth century, the Śvetāmbara Haribhadra had confirmed that monks are permitted to live in temples. In 1024, the caityavāsin Sūra is said to have debated in the Aṇahillapaṭṭana court the virtues of temple-dwelling with Jineśvara, a monk of the newly-founded caityavāsin-opposing mendicant lineage the Kharataragaccha (Dundas 1987–1988, pp. 184–86). By the seventeenth century, temple-dwelling was so common for Śvetāmbara monks that Paṅnyāsa Satyavijayagaṇi led another movement to establish a category of Śvetāmbara monk called a saṃvegī—a “seeker”—who takes the full five vows of Jain mendicancy (Cort 2010, pp. 1–8). |

| 9 | On the role of charismatic Jain renunciants in temple-building projects, see (Babb et al. 2008, pp. 123–24). On the requirement that a Jain monk must consecrate temple images by whispering a potent invocation—the sūrimantra—into the ear of the icons being consecrated, see Dundas (2009, pp. 1–23) and (Gough 2017). |

| 10 | Religious Compositions, Uttar Pradesh, Varanasi, Census of India: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. C-1 Population By Religious Community, Uttar Pradesh. Available online: http://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-01.html (accessed on 3 March 2020). |

| 11 | Fieldwork for this project was first undertaken between 2005–2006, as part of the University of Wisconsin’s College Year in India program. Brief follow-up research trips were made in 2009 and 2016. |

| 12 | See footnote 6. |

| 13 | On the history of Bīsapanthins and Terāpanthins, see Flügel (2006, pp. 339–44). |

| 14 | JAINA: Federation of Jain Associations in North America Newsletter. April 3, 2016. Available online: https://www.jaina.org/page/03_04_16_newsletter (accessed on 3 January 2020). |

| 15 | An inscription below two footprints (pādukā) of the main Supārśva icon established in the temple reads that they were consecrated in 1768 by the Tapāgaccha. |

| 16 | Vinayasāgara (2004, p. 324). A shrine of the footprints (pādukā) of the miracle-working monks of the Kharataragaccha, the Dādāguru Devas, remains in the temple. |

| 17 | Rahul Gandhi, phone interview by author, April 20, 2014. |

| 18 | For a list of a few other smaller Śvetāmbara temples in family homes, see Jain (2013, p. 32). |

| 19 | For a listing of this temple along with eight other Śvetāmbara temples in Varanasi, see Goḷvāḷā (1996, p. 284). For a Gujarati overview of the Śvetāmbara temples in Varanasi, see Bhārat Jain Tīrthoṃno Itihās (1961, pp. 62–67). According to the office manager at the Śvetāmbar Tīrth Society’s office in Bhelūpur, the temples on Nayā Ghāṭ listed in Bhārat Jain Tīrthoṃno Itihās, p. 64 and Goḷvāḷā (1996, p. 284) have been demolished, with the icons moved to the Śvetāmbara temple in Bhelūpur. Phone interview by author, May 6, 2014. |