Popular Songs, Melodies from the Dead: Moving beyond Historicism with the Buddhist Ethics and Aesthetics of Pin Peat and Cambodian Hip Hop

Abstract

1. Introduction: Popular Music and Beyond-Human Listeners

2. Ethnomusicology and the Secular, French Colonialism and Historicism

3. Cambodian–Buddhist Ethics

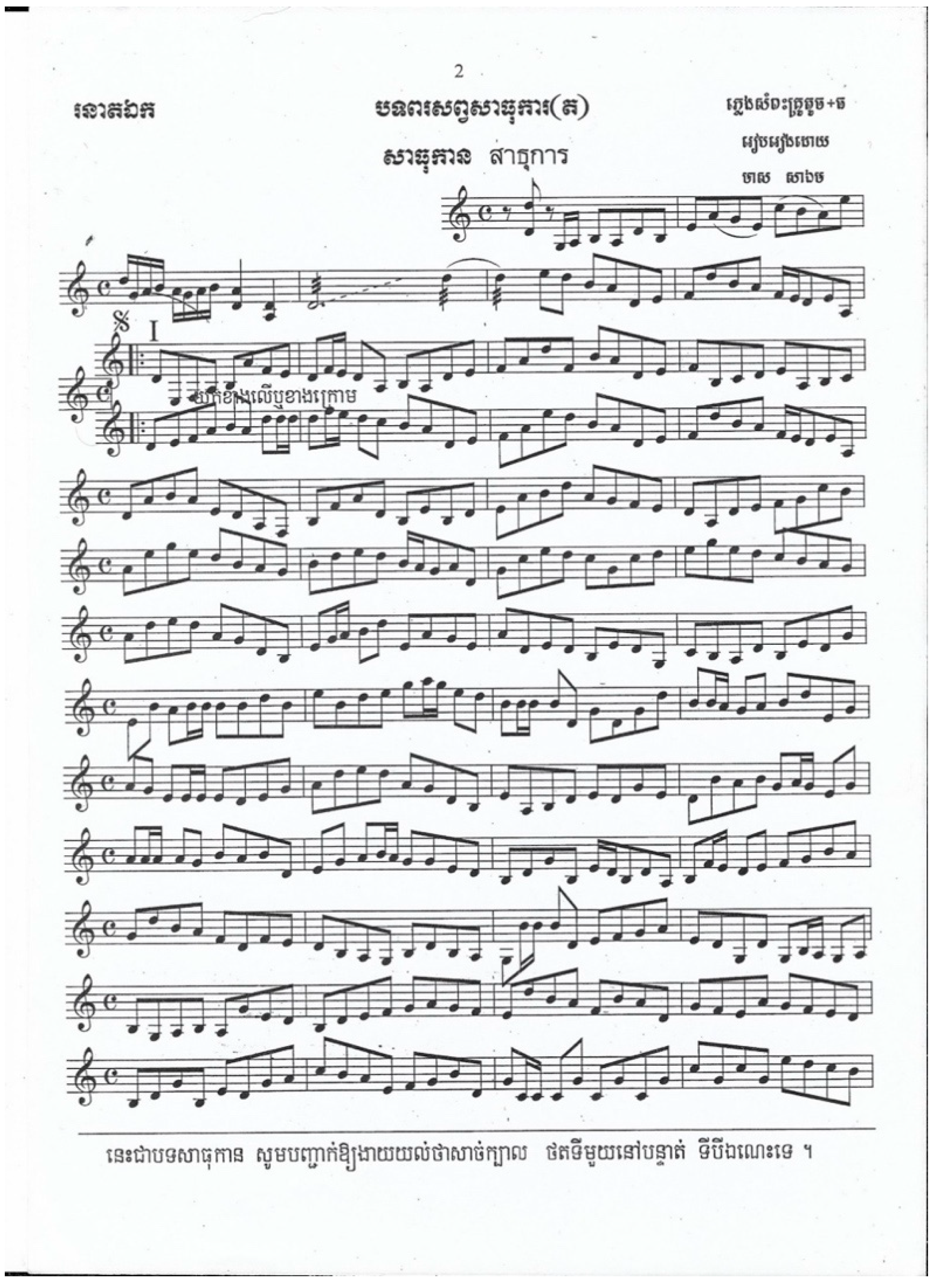

3.1. Playing Melodies from the Dead: Pin Peat’s Buddhist Ethics and Aesthetics

3.2. Copresence and Memory

Keo Dorivan then said that his father’s arrival feels like being possessed, resulting in the positive sensations of support for his arms and physical guidance as he plays. Again, there are several levels of subjectivity, memory, and temporality to unpack, as a shadowy merging of bodies and persons also blurs moments in time, troubling any clean distinction separating a living self from a deceased other and the present from the past. Keo described how present-tense action conjures the memory of a past event in a way that recalls Henri Bergson’s claim that, “it is from the present that comes the appeal to which memory responds, and it is from the sensori-motor elements of present action that a memory borrows the warmth which gives it life” (Bergson 1962, p. 197). However, Keo’s sensation of being possessed or inhabited by his father, who provides energy and support for his arms, both bolsters his cognitive/habit memory and exceeds what a modern conception of memory entails. For Keo Dorivan, his father may be dead, but he is ontologically present, someone whose human existence has run its course but who still intercedes in his life and arrives alongside him when he plays music.So, I recall my father’s variation recalling that, ‘Oh, his hands played like this.’ And so one could say that he is right next to me, in order to help, help me have energy, to help have energy and to remember really well. In previous eras, we didn’t have notation, so we would remember, we would remember by the sensations. And so, we recall the legacies (raṃlẏk guṇ) of our teachers.

It is not just a special song that can give rise to a dead teacher. Rather, playing any melodic variant can recall the legacies of teachers and bring them to take a seat by his side.When I play khluy (flute) or I play any song, I recall my father, and I recall my other teachers, because it is their variation. According to the section of the music I’m playing, I remember those teachers who played it, and they stay beside me through that music’s content.(pers. comm., 9 August 2019)

The sensation of being alongside the dead, which Keo Dorivan and others experience when playing deceased teachers’ variations, is what Po Sakun feels as a “strong moral force” after she does “something good for [her] ancestors”. In the next section, I further explore the diversity of sounds and actions through which Cambodians recall predecessors’ legacies (raṃlẏk guṇ) by considering how relations with the dead arise through music that both involves and exceeds historicist inclinations.When I go any place far away or to any place that I’ve never been before, or when I stay somewhere that doesn’t have safety, I have the feeling that I am scared of bad people who might mistreat me, or I’m afraid of bad ghosts who could harm me. I usually do something good for my ancestors and deities so they can help protect and care for me. At that time, I have a strong moral force and I clearly know at about 90% that I will not have anything happen to me, because my ancestors are alongside me to protect and care for me. So, I’m not scared if I meet a man who I don’t know.(pers. comm., 7 May 2019)

3.3. Partial Connections betweeen Historicism and the Buddhist Ethics and Aesthetics of Cambodian Hip Hop

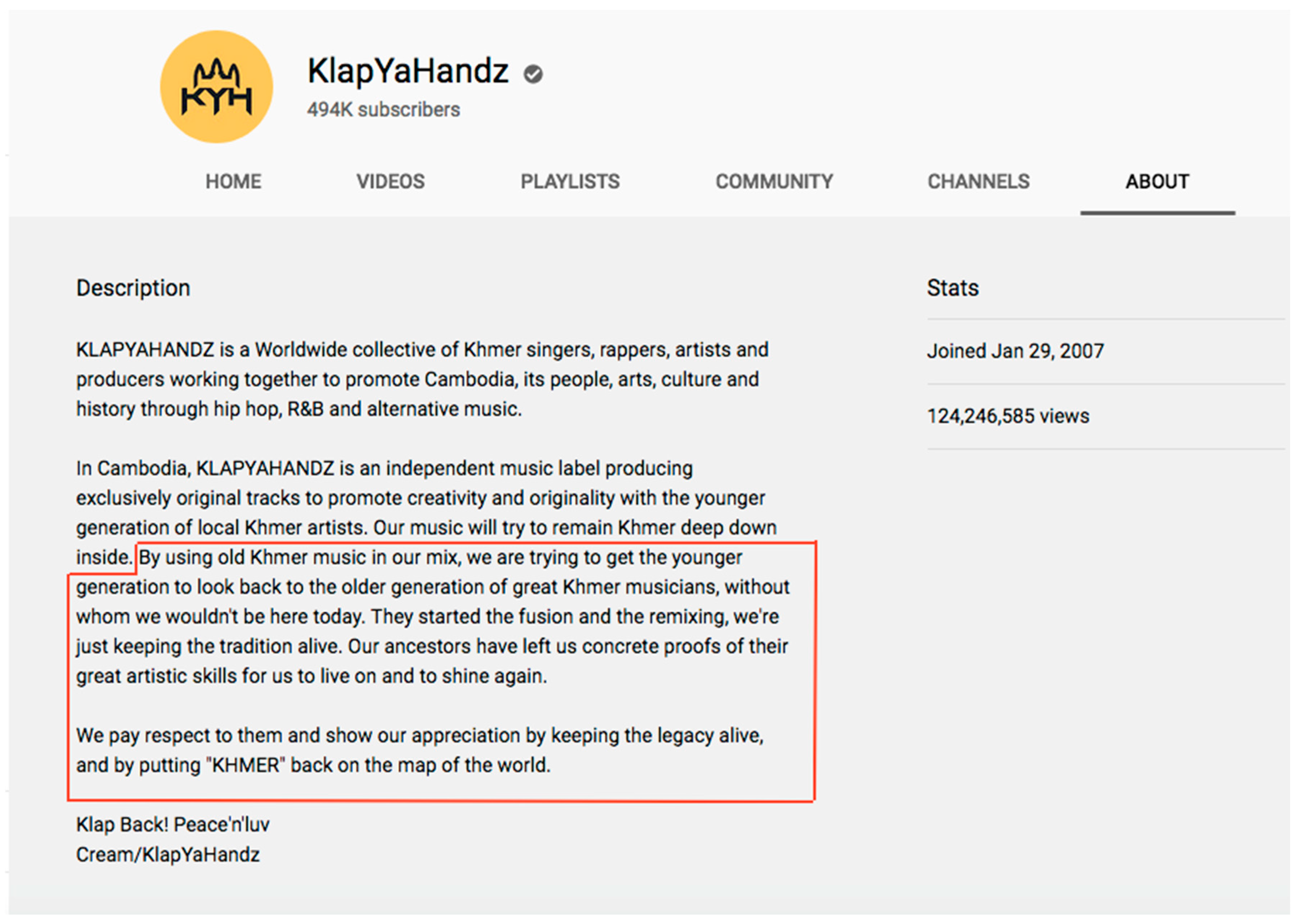

Here, Sok Visal directly acknowledges the debt the younger generation owes to their elders before specifying exactly what constitutes the older generation’s legacy:By using old Khmer music in our mix, we are trying to get the younger generation to look back to the older generation of great Khmer musicians, without whom we wouldn’t be here today.

In contrast to historicism’s search for origins, Sok Visal takes the older generation’s legacy not to be a specific genre or instrument but what he calls a tradition of remixing. Sok directly refers to the generation of musicians who produced Cambodia’s pre-genocide rock and roll, but as Grū Kavei discussed, a similar repurposing of predecessors’ melodies marks pin peat musicians’ practice.They started the fusion and the remixing, we’re just keeping the tradition alive.

Our ancestors have left us concrete proofs of their great artistic skills for us to live on and to shine again. We pay respect to them and show our appreciation by keeping their legacy alive, and by putting “KHMER” back on the map of the World.

4. Epilogue: Completing Another Cycle

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of Religion: Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, Anthony. 1990. Cambodia Will Never Disappear. New Left Review 180: 101–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bergson, Henri. 1962. Matter and Memory. Translated by Nancy Margaret Paul, and W. Scott Palmer. London: George Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, Didier. 2001. The Names and Identities of the ‘Boramey’ Spirits Possessing Cambodian Mediums. Asian Folklore Studies 60: 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeri, Francesca. 2019. Interrelations among Genres in Khmer Traditional Music and Theatre: Phleng Kar, Phleng Arak, Lkhaon Yiikee and Lkhaon Bassac. Ph.D. dissertation, SOAS, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Boyden, Jo, and Sara Gibbs. 1997. Children of War: Responses to Psycho-Social Distress in Cambodia. Geneva: The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, Deirdre. 2009. Shattering Silence: Traumatic Memory and Reenactment in Rithy Panh’s S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 50: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, David P. 1971. An Eighteenth Century inscription from Angkor Wat. Journal of the Siam Society 5: 151–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chigas, George. 2005. Tum Teav: A Translation and Analysis of a Cambodian Literary Classic. Phnom Penh: Documentation Center of Cambodia. [Google Scholar]

- Choulean, Ang. 2004. Brah Ling. Phnom Penh: Reyum Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cravath, Paul. 1985. Earth in Flower: An Historical and Descriptive Study of the Classical Dance Drama of Cambodia. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hawai‘i, Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cravath, Paul. 1986. The Ritual Origins of the Classical Dance Drama of Cambodia. Asian Theatre Journal 3: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupchik, Jeffrey W. 2015. Buddhism as Performing Art: Visualizing Music in the Tibetan Sacred Ritual Music Liturgies. Yale Journal of Music & Religion 1: 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Daravuth, Ly, and Ingrid Muan. 2002. Cultures of Independence: An Introduction to Cambodian Arts and Culture in the 1950′s and 1960′s. Phnom Penh: Reyum. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Erik. 2016. Deathpower: Buddhism’s Ritual Imagination in Cambodia. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de la Cadena, Marisol. 2015. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, Jeffrey M. 2017. Nationalist Transformations: Music, Ritual, and the Work of Memory in Cambodia and Thailand. Yale Journal of Music & Religion 3: 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, Jeffrey. 2018. Oral Pedagogy, Playful Variation, and Issues of Notation in Khmer Wedding Music. Ethnomusicology 62: 104–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Penny. 2004. Making a Religion of the Nation and Its Language: The French Protectorate (1863–1954) and the Dhammakāy. In History, Buddhism, and New Religious Movements in Cambodia. Edited by John Marston and Elizabeth Guthrie. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Penny. 2007. Cambodge: The Cultivation of a Nation, 1860–1945. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Felman, Shoshana, and Dori Laub. 1992. Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giurati, Giovanni. 1999. Bidhī Saṃbaḥ Grū Dhaṃ: Music as Ordering Factor of Khmer Religious Syncretism. In Shamanic Cosmos: From India to the North Pole Star. Edited by Romano Mastromattei and Antonio Rigopoulos. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Giurati, Giovanni. 2018. Performing in empathy: Collective musical improvisation of Southeast Asia. In Free Improvisation: History and Perspectives. Edited by Alessandro Sbordoni and Antonio Rostagno. Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana, pp. 141–61. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Catherine. 2016. Socio-economic concerns of young musicians of traditional genres in Cambodia: Implications for music sustainability. Ethnomusicology Forum 25: 306–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Catherine. 2017. Learning and teaching traditional music in Cambodia: Challenges and incentives. International Journal of Music Education 35: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Anne Ruth. 2007. How to Behave: Buddhism and Modernity in Colonial Cambodia, 1860–1930. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Judith. 2015. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York: Basic Books. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, Alexander. 2018. The Justice Facade: Trials of Transition in Cambodia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Mantle. 1971. Aspects of group improvisation in the Javanese gamelon. In The Musics of Asia: Papers Read at an International Music Symposium held in Manila, April 12–16, 1966. Edited by José Maceda. Manila: National Music Council of the Philippines, pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Mantle. 1975. Improvisation in stratified ensembles of Southeast Asia. Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology 2: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Houseman, Michael. 2006. Relationality. In Theorizing Rituals: Issues, Topics, Approaches, Concepts. Edited by Jens Kreinath, Jan Snoek and Michael Strausberg. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 413–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Dhana. 2013. Violence, Torture, and Memory in Sri Lanka: Life after Terror. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Keo Narom. 2005. Cambodian Music. Phnom Penh: Reyum. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, Stéphanie. 2017. On Periodically Potent Places: The Theatre Stage as a Temporarily Empowered Space for Ritual Performances in Cambodia. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 5: 444–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidron, Carol A. 2009. Toward an Ethnography of Silence in the Lived Presence of the Past in the Everyday Life of Holocaust Trauma Survivors and Their Descendants in Israel. Current Anthropology 50: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidron, Carol A. 2018. Resurrecting Discontinued Bonds: A Comparative Study of Israeli Holocaust and Cambodian Genocide Trauma Descendant Relations with the Genocide Dead. Ethos 46: 230–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KlapYaHandz. 2019. Vol. 1: The Cream of the Crop, 2001–2011. EM Records. Osaka: Japan. [Google Scholar]

- KlapYaHandz. n.d. Available online: http://www.youtube.com/c/KlapYaHandz/about (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Koselleck, Reinhart. 1985. Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kourilsky, Grégory. 2015. La place des Ascendants Familiaux dans le Bouddhisme des Lao. Ph.d. dissertation, École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, Andrew. 2016. ‘Daze of Justice’ explores Cambodia’s trauma of silence. National Catholic Reporter, May 21. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, Jean M. 2013. Consoling Ghosts: Stories of Medicine and Mourning from Southeast Asians in Exile. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood, Judy. 2008. Buddhist Practice in Rural Kandal Province, 1960 and 2003: An essay in honor of May M. Ebihara. In People of Virtue: Reconfiguring Religion, Power and Morality in Cambodia Today. Edited by Alexandra Kent and David Chandler. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, pp. 147–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Sara E. 2019. Spacious Minds: Trauma and Resilience in Tibetan Buddhism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mamula, Stephen. 2008. Starting from Nowhere? Popular Music in Cambodia after the Khmer Rouge. Asian Music 39: 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, Marcel. 1990. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. Translated by W. D. Halls. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- McCollum, Jonathan, and David G. Hebert, eds. 2014. Theory and Method in Historical Ethnomusicology. New York: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, Justin Thomas. 2008. Philosophical Embryology: Buddhist Texts and the Ritual Construction of a Fetus. In Imagining the Fetus: The Unborn in Myth, Religion, and Culture. Edited by Vanessa R. Sasson and Jane Marie Law. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, Justin Thomas. 2011. The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk: Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKinley, Kathy. 2002. Ritual, Performativity and Music: Cambodian Wedding Music in Phnom Penh. Ph.D. dissertation, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhot, M. Henri. 1864. Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos, During the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860. London: John Murray, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mozinga, Joe. 2009. Giving a voice to ‘silent suffering’. Los Angeles Times, April 12. [Google Scholar]

- Muan, Ingrid. 2001. Citing Angkor: The ‘Cambodian Arts’ in the Age of Restoration 1918–2000. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- National Archives of Cambodia. 1942–1943. Résidence Supérieure (RSC) File Number 30145. Box Number 3299. Musique royale et autres musiques du palais. Inventaire des instruments d/orchestra et le nom des musiciens–Statut de musique royale. Phnom Penh, Cambodia. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, Pierre. 1989. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations 26: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, David. 2011. The Sublime Frequencies of New Old Media. Public Culture 23: 603–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmié, Stephan. 2014. Historicist Knowledge and its Conditions of Impossibility. In The Social Life of Spirits. Edited by Ruy Blanes and Diana Espíirito Santo. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 218–39. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, Marc. 2004. Unplayed Melodies: Javanese Gamelan and the Genesis of Music Theory. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peycam, Philippe M. R. 2009. Sketching an Institutional History of Academic Knowledge Production in Cambodia (1863–2009)—Part 1. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 25: 153–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Phuong N., Patrick Vinck, Mychelle Balthazard, Judith Strasser, and Chariya Om. 2011. Victim Participation and the Trial of Duch at the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia. Journal of Human Rights Practice 3: 264–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, John, dir. 2014. Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten: Cambodia’s Lost Rock and Roll. Argot Pictures. [Google Scholar]

- Politz, Sarah. 2018. ‘People of Allada, This Is Our Return’: Indexicality, Multiple Temporalities, and Resonance in the Music of the Ganbgé Brass Band of Bening. Ethnomusicology 62: 28–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, Joseph. 1996. Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Dylan. 2019. Speaking to Water, Singing to Stone: Peter Morin, Rebecca Belmore, and the Ontologies of Indigenous Modernity. In Music and Modernity among First Peoples of North America. Edited by Victoria Lindsay Levine and Dylan Robinson. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, pp. 220–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, Sam-Ang. 1988. The Pin Peat Ensemble: Its History, Music, and Context. Ph.D. dissertation, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, R. Murray. 1969. The New Soundscape: A Handbook for the Modern Music Teacher. Ontario: BMI Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Schechner, Richard. 1985. Between Theater and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanyek, Jason, and Benjamin Piekut. 2010. Deadness: Technologies of the Intermundance. TDR: The Drama Review 54: 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingo, Gavin. 2019. Another Resonance: Africa and the Study of Sound. In Remapping Sound Studies. Edited by Gavin Steingo and Jim Sykes. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, Barry. 2018. Ritual as Action, Performance, and Practice. In The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Ritual. Edited by Risto Uro, Juliette J. Day, Rikard Roitto and Richard E. DeMaris. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, Emiko. 2016. Two Rituals, a Bit of Dualism, and Possibly Some Inseparability: ‘And so that’s how we say that Chams and Khmers are one and the same’. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 31: 786–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarsam. 1975. Inner Melody in Javanese Gamelan Music. Asian Music 7: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, Donald K. 2010. The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia, 2nd ed. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, Jim. 2018. The Musical Gift: Sonic Generosity in Post-War Sri Lanka. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, Jim. 2019. Sound Studies, Difference, and Global Concept History. In Remapping Sound Studies. Edited by Gavin Steingo and Jim Sykes. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 203–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tambiah, Stanley J. 1970. Buddhism and the Spirit Cults in North-East Thailand. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Ashley. 2016. Engendering the Buddhist State: Territory, Sovereignty, and Sexual Difference in the Inventions of Angkor. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Trankell, Ing-Britt. 2003. Songs of Our Spirits: Possession and Historical Imagination among the Cham in Cambodia. Asian Ethnicity 4: 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman-Rosta, Celia. 2014. From Ritual Form to Tourist Attraction: Negotiating the Transformation of Classical Cambodian Dance in a Changing World. Asian Theatre Journal 31: 524–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, Robert. 2006. A burned-out theater: The state of Cambodia’s performing arts". In Expressions of Cambodia: The Politics of Tradition, Identity, and Change. Edited by Leakthina Chau-Pech Ollier and Tim Winter. New York: Routledge, pp. 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Trent Thomas. 2018. Unfolding Buddhsim: Communal Scripts, Localized Translations, and the Work of Dying in Cambodian Chanted Leporellos. Ph.D. dissertation, UC Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Deborah. 2001. Sounding the Center: History and Aesthetics in Thai Buddhist Performance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Deborah, and Rene T.A. Lysloff. 1991. Threshold to the Sacred: The Overture in Thai and Javanese Ritual Performance. Ethnomusicology 35: 315–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun Khean, Keo Dorivan, Y Lina, and Mao Lenna. 2003. Traditional Musical Instruments of Cambodia, 2nd ed. Phnom Penh: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For well-known Khmer terms such as pin peat, I use the common spelling, which typically follows the phonology. On the first instance of those cases, I will provide the orthographic transliteration either in parentheses or a footnote, following the ALA-LC Khmer Romanization Table. For all other Khmer words, I use the ALA-LC’s system. For people’s names, I follow each individual’s preferred spelling. Pin peat’s orthographic equivalent is biṇ bādy. |

| 2 | In addition to “teacher,” the word grū refers to traditional Cambodian doctors, some guardian beings, and even several deities. Many musicians used the term to refer to deities who oversee the music, whom some consider to be their personal teachers. Many also used grū to refer to all the deceased musicians who came before. At times, referring to one’s living music teacher as a grū carries those spiritual connotations. |

| 3 | I distinguish between Khmer—a language and an ethnic category—and Cambodian—a national category in which Khmer is the ethnic majority. The three rhythms are transliterated sār″āv″ân, kandrẏm, and ḷāṃlāv. |

| 4 | I use “Cambodian” rather than “Theravadan” to refer to Cambodia’s main religion. Theravada is a useful category highlighting religious continuities across Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. Several aspects of what I describe resonate with practices in other Theravada Buddhist countries (McDaniel 2011; Swearer 2010, p. 1; Tambiah 1970; Wong 2001). Still, cultural differences remain, and the aesthetic priorities I emphasize may not be prevalent or even present in other primarily Theravada Buddhist countries. |

| 5 | Following a standard usage in music studies, I take aesthetics as particular sounded practices and musical components. Style is a socially constructed category that I will treat as roughly synonymous with genre. |

| 6 | Houseman’s pairing of ritual and relationality is productive, but I diverge from him in two ways. Firstly, Houseman focuses on ritual events such as weddings, funerals, or ceremonies, which Cambodians term bidhī puny. The Cambodians I know conduct the ritual actions and technologies that constitute those ritual events at non-prescribed times and locations, and I consider actions in those contexts to also be rituals. Secondly, Houseman mentions human–nonhuman relationality, but he emphasizes rituals’ efficacy for human–human relationality; Cambodian practices bring me to flip the emphasis. I take ritual in this context to be any action that enacts or enhances relations with deities and the dead. Religion indicates a broad system that includes theological tenets and texts, moral principles, monastic and bureaucratic structures, and ritual practices. By “religious,” I denote actions and experiences that involve any aspect of a religion’s principles, ethics, or aims. |

| 7 | Following Castro, de la Cadena defines equivocation as “a type of communicative disjuncture in which, while using the same words, interlocutors are not talking about the same thing and do not know this.” Translations acknowledge those inevitable differences and attempt to communicate through them (de la Cadena 2015, p. 27). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | What most music scholars now term heterophony is what Mantle Hood termed stratified polyphony. |

| 10 | For instance, Perlman’s stated objective is to trace “a cognitive process of creativity,” and he writes that “by helping us understand how musicians come to think in new ways about their music, it may even fill a lacuna in the historiography of Western music theory” (Perlman 2004, p. 8). |

| 11 | George Groslier used the perception of decline to establish these institutions. He directed the school’s visual arts curriculum (Muan 2001) and later brought royal dance to the school (Cravath 1985, pp. 187–88). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Such continuity even resulted from Cambodian modernizers’ objectives. As Hansen writes, “the French wanted (for themselves and their Khmer colleagues) to be modern in their understanding of Buddhism; the Khmer wanted to be Buddhist in a modern world” (Hansen 2007, p. 131). Additionally, I have described how the opening lyrics Chuon Nath composed for Cambodia’s national anthem do the work of a ritual inviting deities to protect the nation (Dyer 2017). Among other Buddhist traditions, McDaniel describes a case in Thai Buddhism in which surface modernization does not displace ritual function (McDaniel 2008). Sykes writes that “sonic efficacy, astrology, and drumming…[remain] intimately tied to Buddhism as it is practiced in Sri Lanka” despite colonial Christian missionaries’ best rationalizing efforts (Sykes 2019, p. 221). |

| 14 | On Cambodian visual art, Ingrid Muan writes, “But within the turn of the [twentieth] century society in which these forms were being produced, their meaning lay much more in their use for ceremonies of worship and everyday life than in a visual contemplation that turned them into objects with purely aesthetic and financial value” (Muan 2001, p. 9). My point is that aspects of that “society” remain active in the twenty-first century. |

| 15 | Performance’s multivalence seems to persist. Cambodian dancers in Siem Reap say “their practice is still spiritual even if they are performing for tourists,” and the dance serves “a dual duty as sacred ritual and as a form of secular entertainment” (Tuchman-Rosta 2014, p. 539). |

| 16 | Grégory Kourilsky notes that guṇ means “quality” or “virtue” on the Indian subcontinent and later came to mean “legacy” and “debt” in mainland Southeast Asian contexts (Kourilsky 2015, cited in Walker 2018, p. 19). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | This argument for Buddhism’s popular and everyday ethics diverges from analyses that follow Max Weber in distinguishing between Buddhism as “a cultural institution and an ethical system” (Swearer 2010, p. 1). |

| 19 | In a prevalent Cambodian notion of self, each person has nineteen vital spirits (Choulean 2004; Davis 2016). |

| 20 | This shelter resembles a shrine house, but I avoid that term because of its potential association with relics. The objects inside are not relics but statues of the deity, which some take to manifest the deity himself. Most villages in Cambodia have a shelter for the local tutelary being(s). Another shelter where musicians play music regularly is that of Braḥ Angg Cek and Braḥ Angg Cam in Siem Reap’s provincial capital. |

| 21 | Riel (rial) is Cambodia’s currency, and it exchanges at roughly 4100 riel for $1 USD. In street transactions, sellers often exempt the 100 riel when receiving dollars, making 5000 riel equivalent to $1.25. |

| 22 | Steingo refers to a common trope in sound studies, particularly work on mobile listening devices. His point is similar to mine, that the widespread assumption that sound technology universally alienates and isolates is geographically particular. Steingo notes how sound technologies connect people across perceived spatial barriers; in this example, they build relations by compressing chronological time. Cambodian musicians also use technology to develop intimate relations with dead musicians by studying from recordings on YouTube. |

| 23 | McCollum writes, “History, after all is what actually happened” (McCollum and Hebert 2014, p. 231), and McCollum and Hebert take historiography to involve “rigorous examination and critique of extant sources on a topic” (p. 362). |

| 24 | Even when a gift “has been abandoned by the giver, it still possesses something of him.” Thus, “it follows that to make a gift of something to someone is to make a present of some part of oneself,” and “to accept something from somebody is to accept some part of his spiritual essence, of his soul” (Mauss 1990, p. 12). |

| 25 | Cambodian ethnomusicologist Keo Narom writes that by the late nineteenth-century a brass ensemble termed “the Manila ensemble” had begun playing at Cambodia’s Royal Palace, and she surmises that the “Spanish Governor” of the Philippines may have provided Cambodia’s King Norodom with Filipino musicians along with the soldiers he gave to the monarch following his 1872 visit to Manila (Keo Narom 2005, pp. 90–91). By 1943, 34 Cambodian musicians plus an ensemble leader played such instruments as a clarinet, trumpet, various saxophones, and a bugle for Cambodia’s royal music fanfare (National Archives of Cambodia 1942–1943, RSC #30145). |

| 26 | This neo-colonialist preoccupation with Cambodian arts’ precarity also marks much scholarship and some activism on traditional performing arts, including Robert Robert Turnbull’s (2006) and Catherine Grant’s (2016, 2017) work on the endangerment and challenges facing Cambodian arts. See Anthony Barnett (1990) for a vigorous critique of the enduring colonialist construct of Cambodia’s national endangerment. |

| 27 | In English, these song titles are “Saravan Wearing the Wind” and “Wearing the Wind, Covered by the Sky”. Both phrases are poetic ways of rendering “to be naked,” the latter title giving the full expression. The two titles transliterate as “Sārāvân Sliak Khyál” and “Sliak Khyál Ṭaṇṭáp Megh”. All of the versions I discuss are available online. For So Savoeun’s version, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_DHUEt8QySo. For one of Touch Sreynich’s versions, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TRS3XDJhZ3E. For Bross La’s “Saravan Remix”, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hQbRPQIqrmQ. For Sreyleak’s version, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D4j6FcCUlfg. |

| 28 | The tā lung rhythm is likely of Lao origin and resembles the eponymous saravan rhythm. |

| 29 | On 21 October 2003, Touch Sreynich was shot several times while shopping with her mother in Phnom Penh. Her mother died from a single bullet wound sustained during that attack, and Touch was paralyzed below her neck. The crime remains unsolved, but it is highly likely that it was politically motivated. Touch had recently released an album with controversial political content, and her attack occurred only three days after the murder of a journalist employed by a radio station critical of Prime Minister Hun Sen. |

| 30 | Other examples of hip hop songs that foreground traditional instruments include Kelly’s 2007 song “K.E.L.L.Y,” Pou Khlaing’s 2008 song “Yeak,” and Yungsterz’s 2008 song “Luk Ko Luk Krobey,” all of which appeared on the music label KlapYaHandz’s sole album, first released in 2012 (KlapYaHandz 2019). |

| 31 | The saravan–hip hop mixture seems to be a burgeoning style of music. On YouTube, see Sreyleak’s “Saravan Rok Ku” and Pou Khlaing’s “SaRaVan HipHop” as examples that seem to cite predecessors’ legacies. Bross La’s “The New Saravan” seems to prioritize updating rather than honoring an old form. |

| 32 | These ideas embody the common assumption in trauma studies that narrative testimony enacts justice and healing (Felman and Laub 1992; Herman [1992] 2015), a notion Carol Kidron trenchantly critiques (Kidron 2009). |

| 33 | For instance, take Pham et al.’s finding that, out of the seventy-five Cambodian nationals who volunteered to provide testimony during the Khmer Rouge Tribunal’s Case 001, “none of the Cambodian civil parties described a catharsis or healing effect” (Pham et al. 2011, p. 284). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dyer, J. Popular Songs, Melodies from the Dead: Moving beyond Historicism with the Buddhist Ethics and Aesthetics of Pin Peat and Cambodian Hip Hop. Religions 2020, 11, 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110625

Dyer J. Popular Songs, Melodies from the Dead: Moving beyond Historicism with the Buddhist Ethics and Aesthetics of Pin Peat and Cambodian Hip Hop. Religions. 2020; 11(11):625. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110625

Chicago/Turabian StyleDyer, Jeffrey. 2020. "Popular Songs, Melodies from the Dead: Moving beyond Historicism with the Buddhist Ethics and Aesthetics of Pin Peat and Cambodian Hip Hop" Religions 11, no. 11: 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110625

APA StyleDyer, J. (2020). Popular Songs, Melodies from the Dead: Moving beyond Historicism with the Buddhist Ethics and Aesthetics of Pin Peat and Cambodian Hip Hop. Religions, 11(11), 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110625