1. Introduction

Frederick Jackson Turner claimed that the American frontier had shaped America and defined the characteristics of being American. Turner was an American historian whose “frontier thesis” posited that the Western Frontier drove American history and, as a result, explained why America is what it is. The frontier concept facilitated a certain rugged individualism in those who explored it. In this manner, Turner argued, the story of this continual westward push “with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnished the forces dominating American character” (

Turner 1998, p. 27). Turner’s seminal essay outlining his thesis was first presented at a special meeting of the American Historical Association at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and published later that same year. Well regarded for many years, Turner’s framing of American history began to be challenged in the early 1940s.

In

Destined for the Stars: Faith, the Future and America’s Final Frontier, Catherine L. Newell expands on Turner’s argument that outer space is a frontier waiting to be explored, arguing that the foundation of the conquest of space is actually a religious endeavor (

Newell 2019, p. 12). From the end of the Second World War to the beginning of the Cold War, Newell contends that the exploration of space was a “spiritual necessity” that resulted from our need “to escape the inevitable cataclysm that would befall Earth” (

Newell 2019, p. 4). She contends that the exploration of space was not undertaken solely as a result of technological or economic superiority or by a national effort motivated by political and ideological fears. Rather, the success of the US space program was due to “a culture that had long valued faith above other religious feeling and believed they were called by God to settle new frontiers and to prepare for the end of time” (

Newell 2019, p. 5). The move west, which began with a fear that the end of the world was coming and that the New World needed to be purified of the sins of the Old, led to the conquest of the frontier. This was then interpreted, by extension, as a religious calling, a divine sign that God had a hand in the lives of His chosen people. Newell concludes that this idea mapped perfectly onto a future in space because after all “how could a country that had tamed the great North American frontier not succeed in conquering the final frontier?” (

Newell 2019, p. 17).

With the closing of the American frontier, there emerged an active campaign during the Cold War to try and reinvent that nineteenth-century faith as described by Newell by replacing the old frontier of the American West with the New Frontier of outer space. In describing space as the New Frontier, I show how most Americans first came to interpret, understand, and support space exploration through a campaign that began with John F. Kennedy’s successful “New Frontier” presidential bid of 1960, which reawakened a sense of manifest destiny in postwar America by reviving the same ideals that characterized the pioneers that opened the now closed Western frontier. Kennedy depicted human spaceflight as a great pioneering adventure, an epic saga that made it possible for the early space program to thrive not only in the eyes of the public, but also in the chambers of Congress.

An examination of the rhetoric of the New Frontier requires not only historical context but also an analysis of the elements that make up a good saga such as a conquerable location, a malevolent antagonist, and a heroic adventurer. Add to this the spiritual justification that Newell argues never really went away, and together, you now have a narrative appealing to a Cold War audience nervous about nuclear annihilation. This essay identifies these narrative elements and illustrates how they were adapted and applied to the New Frontier of outer space.

The New Frontier rhetoric spread to NASA, which became a federal agency just a few years before Kennedy first took office as president in 1961 (

Kennedy 1961a). In

Space: The New Frontier, one of the first popular publications produced by NASA shortly after the agency’s formation in 1958, I show how NASA sought to capitalize upon the New Frontier narrative to help educate a skeptical public about the new agency’s goals and to help convince a reluctant Congress to fund its programs. The influence of James Fletcher, one of the longest serving NASA Administrators, is also examined, revealing how his frontier-focused Mormon upbringing may have influenced his policies and ideals.

The use of the New Frontier theme as it appears in print media is explored, starting with the unique relationship that NASA had with Life magazine. NASA saw the magazine and its other publications as a vehicle for popularizing the space program. Life’s trademark oversized format with a heavy emphasis on photos provided a perfect forum to portray the enormity of outer space. Together, they successfully depicted the vastness of the New Frontier and all its awe and wonder to readers, many of whom could not help but see the spiritual allegory unfold on its pages. In addition, numerous trade publications sprang up in support of the growing field of aerospace, featuring advertisements illustrating hardware that were not only designed to get us into space, but also drawn to secure the contracts and hire the workers that would build it. Samples of this advertising are examined along with interpretations of their spiritual meaning.

Finally, this paper explores how the rhetoric of the New Frontier was used in television and other media, such as in Walt Disney’s newly opened Disneyland theme park and in assorted record albums to help further engage the public imagination, and concludes with a discussion of how a New-Frontier-influenced national space rhetoric and its associated religious overtones saw a resurgence in America since the end of the Cold War, particularly in space activism and policy that began under the Reagan administration that continues to this day.

2. Kennedy, Congress, and the New Frontier

The New Frontier was the name given to the Kennedy campaign for the Presidency. As John M. Logsdon writes, Kennedy may well have won the 1960 election “partly because of space-related issues”, which were a pivotal part of his campaign (

Logsdon 1970, p. 64). In the 1985 Pulitzer Prize-winning book

The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age, historian Walter A. McDougall points out that no single campaign issue “better symbolized” Kennedy’s “New Frontier” (

McDougall 1985, p. 221).

On July 15, 1960, during the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, Senator Kennedy gave a speech upon accepting his Party’s nomination as their candidate for the 1960 presidential election. Later known as “The New Frontier” speech, it featured Kennedy using the term “frontier” thirteen times. Two good examples include: “the new frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises—it is a set of challenges. It sums up not what I intend to offer the American people, but what I intend to ask of them” and “we stand today on the edge of a new frontier—the frontier of the 1960s—a frontier of unknown opportunities and perils—a frontier of unfulfilled hopes and threats” (

Kennedy 1960a). In the spirit of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, which itself was derived from Woodrow Wilson’s New Freedom program, the phrase referenced the uncharted decade of the 1960s and how it could be perceived as a New Frontier for exploration.

In remarks given at a Civic Center in Denver not long after formally accepting the Democratic Presidential nomination, Kennedy said, “I think you can get a clear contrast between our two parties in the slogans the Presidents have run on in the 20th century. No Democrat ever ran on ‘Stand pat with McKinley’, or ‘Keep cool with Coolidge’, or ‘Return to normalcy with Harding’, or ‘No new starts in 1960’, or ‘You never had it so good’. Our Presidents have run on the rights of man, with Thomas Jefferson, the New Freedom of Woodrow Wilson, the New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt, the Fair Deal of Harry Truman, and now we seek a New Frontier, not only for the United States, but for all those who wish to follow us on the road to freedom” (

Kennedy 1960b).

For the Kennedy campaign, the New Frontier theme was first suggested by Walt Rostow, a member of Kennedy’s Academic Advisory Group (AAG), who presented the idea to Kennedy at a cocktail party for the group held in Dierdre Haderson’s home. It was also Rostow who wrote Kennedy’s “New Frontier” speech (

Harzis 1996, p. 33). The AAGwas a small assembly of academics that Kennedy gathered to help advise him on policy and to draft speeches. Similar to the “Brains Trust”, a group of academics from Columbia University that Franklin Roosevelt used to help draft his election campaign and later employed by his administration to craft the New Deal, the AAG was comprised of several dozen academics from in and around Boston. Kennedy began to assemble this group in 1956 when he first became a national public figure at the Democratic convention where he sought to become his party’s Vice-Presidential nominee. Membership in the AAG was bipartisan and fluid. “Kennedy seems to have cared little for the various political persuasions of these scholars. He cared much more about their ideas and opinions,” wrote Panagiotis Harzis, who explored the origins of the AAG (

Harzis 1996, p. 5).

This AAGwas highly effective in helping Kennedy incorporate the rhetoric of the old frontier to help define the symbolism and optimism of his New Frontier presidential campaign. David Zarefksy writes that President Kennedy’s New Frontier campaign “became a meaningful symbol when it received widespread use and when the related images of discovery, exploration, charting a course, and pursuing the unknown were given expression” (

Zarefsky 1986, p. 17). The AAG’s guidance helped Kennedy give these images persuasive meaning by effectively depicting them in a frontier narrative that many critics found challenging to counter because the story was so persuasive.

The frontier adventure story transcends the debate on the pros and cons of the need for man to travel into space. Olin Teague, chairman of the powerful Manned Space Flight Subcommittee, noted that before the space race, America believed there were no more first-class “challenges”, no more “new frontiers.” He concluded that the idea of lunar exploration had “reawakened” America’s “spirit of adventure and achievement” like nothing since “the days of the pioneers” (

United States Congress 1963, p. 13855).

James Kauffman wrote in

Selling Outer Space: Kennedy, the Media, and Funding for Project Apollo, 1961–1963 that the Kennedy “administration also depicted the manned lunar landing in narrative form as a great frontier adventure, complete with heroes and villains. Although critics would question the political, scientific, military, and economic justifications for sending a man to the Moon, the frontier narrative went unchallenged. Both the media and Congress found the story irresistible. In short, the frontier narrative stood as the most powerful justification for a manned Moon mission” (

Kauffman 1994, p. 29). Kauffman concludes, “with the cold war in full swing, Americans wanted desperately to have faith in a viable narrative that held out hope for America’s future” (

Kauffman 1994, p. 131). The space rhetoric used during the Kennedy Administration emphasized a deep-rooted frontier narrative in American history and culture that allowed the early space program to succeed. “Americans wanted to believe the myth of the frontier adventure”, said Kauffman, (

Kauffman 1994, p. 131) and depicting human spaceflight as a great pioneering adventure, this myth could not easily be refuted by the media, public, or Congress. In describing space as the New Frontier, Kennedy paved the way for how Americans came to interpret, understand, and support space exploration by recreating part of America’s cultural mythology of its past.

During the 1960 presidential campaign, President Kennedy exploited a growing public concern about the space race that was fueled by an assertion of a “missile gap”, a fear-inducing falsehood that his party put forth at the expense of the Eisenhower administration. This feeling of technological inadequacy was further enhanced by a series of successive Soviet space spectaculars that, when compared to early American launch failures, created a public fear that the United States had indeed fallen behind their Russian counterparts, especially in the production of missiles.

In the October 10, 1960, issue of

Missile and Rockets, Kennedy issued a campaign statement on space: “We are in a strategic space race with the Russians, and we are losing… Control of space will be decided in the next decade. If the Soviets control space, they can control Earth, as in past centuries the nation that controlled the seas has dominated the continents. This does not mean that the United States desires more rights in space than any other nation. But we cannot run second in this vital race. To insure peace and freedom, we must be first… This is the new age of exploration; space is our great new frontier” (

Kennedy 1960c, pp. 12–13).

For those who lamented the closure of the Western frontier, there now emerged the New Frontier of space that allowed fearlessness, rugged individualism, and other American qualities to re-emerge in the face of imminent danger posed by the Soviet Union. The added threat posed by a foreign power heightened the religious certainty that God wanted Americans to go out into space as the New Frontier. God would not let us fail, so what does He want us to do in space? That answer came less than three weeks after astronaut Alan Shepard splashed down in his Mercury spacecraft, marking the first time an American had flown into space. On 25 May 1961, President Kennedy addressed a joint session of Congress that included an audacious plan to land a man on the Moon.

3. Narrative Elements of the New Frontier

Kauffman points out that in order for the frontier narrative to be successfully applied to the New Frontier, adjustments had to be made. “To ring true, a frontier story must possess specific constituent elements: (1) an identifiable, conquerable geographic location that is (2) unknown and hostile and includes (3) a malevolent antagonist who is thwarted by (4) a heroic adventurer” (

Kauffman 1994, p. 34). In addition, Janice Hocker Rushing in

Mythic Evolution of ‘The New Frontier’ in Mass Mediated Rhetoric shows how Kennedy altered the frontier myth in order to relocate it from the pioneering frontier of America’s West to the New Frontier of space. In her work, Rushing suggests that central to a frontier adventure, one needs to define the “scene” and the “hero.” Rushing notes that the scene is an identifiable, tangible geographic location that could be conquered and dominated. However, this definition is difficult to apply to outer space. The physical act of going into space is a challenge but once that is done, what is there next? Unlike the “Old Frontier,” one cannot conquer space by simply going there or by having others occupy it, since space is infinite and can never be conquered by filling it up (

Rushing 1986, p. 283).

Stephen Pyne notes that advocates who have expanded the story of Western American settlement to encompass space exploration encountered problems, because “discovery among the planets is qualitatively different from the discovery of continents and seas” (

Sagan and Pyne 1988, pp. 14, 18). For the Kennedy Administration, this problem was solved by establishing a clear concrete goal for the space narrative of their New Frontier campaign: that of landing a man on the Moon. Landing men on the lunar surface fulfilled not only an identifiable, conquerable geographic location, but was also unknown and hostile.

Space is harsh and full of danger, but by itself, it is not an effective malevolent antagonist. Something else is needed. In the Soviet Union, Kennedy found his needed malevolent antagonist in the Russians who, like the Native Americans that threatened expansion into the Western frontier, served to threaten America’sentry into the New Frontier of space. Kennedy did not always call out the Soviets directly by name, but he was clear in pointing out that they sought “to dominate space” and their “intentions” toward it “may be hostile” (

Kennedy 1961b, p. 560). NASA Administrator James Webb did not mince words, calling the Soviets “a powerful despotism, bent on burying us along with the basic tenets upon which our society rests and from which it draws its strength” (

Webb 1961, p. 98).

The last element needed to successfully make a frontier story is a suitable hero. The “star voyager” or astronaut of the New Frontier of space had to exemplify traditional American values of the frontiersman of the West: courage, patriotism, and a fierce self-reliance, combined with the added qualities of humility, discipline, and religious devotion like those that characterized their Puritan ancestors. These pioneers of the New Frontier of space had to be part Daniel Boone and part Flash Gordon. America’s first astronauts exemplified all of these traits. The press, members of Congress, and the general public all focused their attention on the astronauts, for “rarely were history’s explorers and discoverers so clearly marked in advance as men of destiny” (

Barr 1959, p. 7). Among the first seven astronauts that NASA selected for the Mercury program, one stood out as having exemplified all the traditional American values associated with our pioneer ancestors.

John Glenn was the quintessential American astronaut who held the enviable position of being more perfect than his NASA colleagues. “[America] found Glenn the man fully the equal of Glenn the astronaut” wrote

Time magazine (

Time 1962, p. 22). The media adored Glenn, and it was through them that the American public learned how the career Marine exemplified the heroic qualities of his Puritan pioneers that settled the Western frontier. According to

Time magazine, “Glenn’s modesty, his cool performance, his dignity, his witticisms, his simplicity—all caught the national imagination” (

Time 1962, p. 22). However, it was his faith and not his adventures in space that garnered the most public attention.

The press described Glenn as “deeply religious” and reported that he and his family attended church “every” Sunday (

Newsweek 1962, p. 20). In the eyes of the public, Glenn was the hero element of the frontier narrative. His orbital mission received the greatest amount of media coverage during the Mercury Program. He was portrayed as the heroic adventurer, one of many, like the courageous and patriotic early pioneers who adventured before him to settle the West. After his successful flight, Glenn was invited to give a speech before a joint session of Congress. During the speech, many members of Congress were visibly moved by what he said. Dora Jane Hamblin, in writing about Glenn’s speech, described his words in near messianic terms, stating that it created “a deep silence, full of cleansing rejuvenating pride in him, his family, and the nation” (

Hamblin 1962, p. 35). Glenn’s flight offered a baptism that cleansed the nation of its transgressions caused by its late start in the race for space. His successful mission rejuvenated the nation toward believing it could reach Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon before the decade was out. Glenn had spoken, and as Hamblin wrote, his “star-spangled sincerity evoked the pride of a nation of a far more innocent age” (

Hamblin 1962, p. 34).

4. NASA and the New Frontier

Soon after NASA was formed, it issued

SPACE The New Frontier (see

Figure 1), an illustrated popular publication designed to help explain to the general public what the new federal agency was all about. The publication proved to be so popular that NASA continued publishing it over the next seven years, revising it to reflect its changing goals. In the first edition that came out in 1959, it featured a stylized Sun in the center of the cover, around which appear concentric painted orbits. Throughout the insides are samples of artwork depicting fictional rockets flying through space, imagery popular in the late 1950s and designed to capture the public’s imagination.

The cover design of the next edition, which came out three years later, shows the Moon, Mars, and another planet (perhaps Venus?) orbiting the Earth with a stylized human figure standing nearby. Unlike the first cover, this edition presents recognizable objects within the solar system. By showing these objects and their relative proximity to the Earth, it suggests that they are all within NASA’s reach as the space agency began to more clearly define its role in the exploration of the New Frontier and man’s place in it. Conspicuously absent however are the pulp-like artwork depictions of space travel, now replaced by photos showing real hardware designed to convey a message of confidence and maturity in what NASA was doing.

In the third edition that came out in 1963, NASA evolved from using simple spot color on its cover to a more expensive four-color printing that showcases a brilliant telescopic image of the Orion Nebula. The 1964 edition features this same cover photo but with the addition of a white silhouette of the Apollo spacecraft moving left to right across the bottom. The intent was clear—by including the spacecraft that would take men to the surface of the Moon and back, NASA hinted that the lunar landing was just the beginning and that travel to the stars was also within its reach. The last issue, which came out in 1966, features a cover showcasing a Saturn V on the launch pad. This image conveyed to the reader that NASA was ready to go to the Moon, even though the rocket depicted was the Saturn V Test Article (SA-500F), an engineering mockup that was never designed for actual spaceflight. The first actual test flight of the Saturn V would not occur until November of the following year with the launch of Apollo 4.

Kapell argues that national space rhetoric, particularly that dealing with the frontier, had been part of NASA’s institutional culture and its public face since the beginning of its formation (

Kapell 2015). He points out that Congressional Hearings in 1960 accepted that “we yield to the urge to explore that is an American heritage” (

NASA 1960, p. 159). This is an interesting example of American exceptionalism—the idea that we conquered North America and so are a conquering type of people and somehow different from others like those in the Soviet Union, which does not have a similar history (ignoring Canada, Brazil, and other New World nations). By 1965, Kapell concludes, “NASA had fully accepted the mythic frontier underpinnings of their overall project, proclaiming that its missions were ‘exploration in the truest and most romantic sense’ and that space was, therefore, ‘the most recent of these ‘last’ frontiers’ of such exploration” (

NASA 1965, p. 2). In talking about America’s adventures in space, NASA had to walk a fine line. The astronauts could say what they liked, but they were always under the watchful eye of their NASA keepers. Those in authority had to be more circumspect to avoid coming across as religious zealots on course to the stars via a crusade. “With its hint of the discoveries of fundamental truths concerning man, the earth, the solar system, and the universe,” noted a 1958 government document, “space exploration has an appeal to deep insights within man which transcend his earthbound concerns” (

Coffman and Sampson 1991, pp. 845–63).

By no means was the American civil space program a bastion of secularism, but neither was it a Christian stronghold. Oliver observed that “the space program, for all of the Christians in its midst, for all of its evocations of transcendence, was a product primarily of profane, sometimes prosaic, ambition. For the most part, indeed, it serves as an object study in differentiation: religious values and symbols often did make the commute from suburban altar to NASA space center, but they were usually weakened by the journey, to the point where they exerted no autonomous authority over the substance and direction of space policy” (

Oliver 2013, p. 43). Oliver’s observation is not entirely true, however, as one of NASA’s longest serving administrators demonstrated that one’s religious upbringing can bear an influence on how America would explore the New Frontier of space.

James Chipman Fletcher was the eldest of five sons and one daughter that was born of pioneering Mormon stock. He and his siblings all obtained academic degrees with four of the boys, including James, earning Ph.D. degrees in science. After obtaining a B.A. in physics from Columbia University in 1940, Fletcher worked in the war effort, using his physics background in various research capacities including a fellowship at Princeton. Soon after the War ended, he completed a Ph.D. in physics at Caltech.

Demonstrating an exceptional blend of both management and technical skills, Fletcher worked for various aircraft companies, including Hughes Aircraft in Los Angeles and the Ramo-Woolridge Corporation, where he worked on ICBMs. His unique abilities to both manage and do new research in the burgeoning aerospace field eventually led him to form his own company.

Fletcher’s success in business allowed him to return to academia, where he became the president of the University of Utah in 1964. During his business career and all the while University President, Fletcher continued serving in various government capacities that included both NASA and its predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). In 1967, Fletcher was appointed by Lyndon B. Johnson to serve on the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC), a committee that he had consulted since 1958 when it was first organized.

In the wake of the monumental successes of the Apollo Program, President Nixon sought someone who would lead NASA with a less costly vision as the agency struggled to define itself in the wake of the post-Apollo period. Administrator Thomas Paine, who lead NASA after Jim Webb left just prior to the Apollo 8 mission in 1968, was reluctant to slow the “go fever” that drove NASA to achieve Kennedy’s lunar landing goal. Now that the Apollo Program was over, Paine presented plans for NASA to a skeptical Nixon that included building a space station and sending humans to Mars. Nixon demurred and Paine soon stepped down. After Paine left NASA, he was replaced by Fletcher, who was sworn in by Nixon on 27 April 1971, and served as the head of NASA until 1 May 1977. After the Challenger accident, President Reagan asked Fletcher to return to help reorganize the agency. Fletcher stepped down from civil service on 8 April 1989.

During his lengthy tenure at NASA, Fletcher got caught up in America’s national space rhetoric, even alluding to his Mormon ancestors: “History teaches that the process of pushing back frontiers on Earth begins with exploration and discovery is followed by permanent settlements and economic development. Space will be no different… Americans have always moved toward new frontiers because we are, above all, a nation of pioneers with an insatiable urge to know the unknown. Space is no exception to that pioneering spirit” (

Fletcher 1987).

Fletcher was quick to seize on religious allegory that blended his Mormon ideals with the goals of NASA and the New Frontier of space. Mormon cosmology embraces not only the possibility of other worlds, but also the fact that they might be inhabited by intelligent life. The story of the Mormon faith is steeped in pioneer mythology and fits nicely into the broader Christian view of manifest destiny. Reeling from the murder of Joseph Smith, their founder and prophet, the Latter Day Saints (also known as the Mormons) supported a new leader named Brigham Young. In 1844, Young led the Mormons on a westward trek through some 1300 miles of mountain wilderness—a rite of passage they saw as necessary by God in order to find their promised land, a new Israel in North America. They settled into the Great Salt Lake Valley of what would eventually become the state of Utah. In the succeeding decades, wagon trains bearing thousands of Mormons followed Young’s original westward passage on a path known as the Mormon Trail. The story behind the Mormon faith inspired Fletcher, who drew parallels between Abram leaving Ur and settling in Haran and the desire of mankind to push back frontiers, openly thinking that a “God-given desire will likely result in the colonization of space and a manned voyage to Mars by the end of the century” (

Church News 1986).

Perhaps Fletcher’s single biggest legacy to America’s space program was in helping assure that NASA survived. As NASA struggled to define its role in the wake of the Apollo Program, the agency’s very existence hinged upon a controversial decision in 1972 to build the Space Shuttle. Fletcher argued that the Space Shuttle was necessary to continue opening up the New Frontier of space. Even after President Nixon supported the decision to build it, Fletcher continued to make use of the pioneering Mormon allegory, as it remained an effective tool during the post-Apollo period. In comments he made in 1974, Fletcher noted that “the covered wagon and the railroads were not just transportation systems of their day, they helped earlier generations of Americans open a continent. In similar fashion, the Space Shuttle will open the new realm of near-Earth space for all mankind.” He concluded that, “there is no new frontier in space for America and for mankind without the Shuttle” (

Fletcher 1974, p. 42). Spaceflight historian and Mormon scholar Roger Launius, in writing about James Fletcher, notes that the long-serving NASA Administrator, in spite of his open religious views, was an effective leader of the agency, because he sincerely “believed that science and technology possessed the possibility of resolving most of the world’s problems if they were used properly by a powerful, benevolent government” (

Launius 1995, p. 238).

5. Print Media and the New Frontier

In 1936, America was introduced to

Life, America’s first modern picture magazine. Founded by Henry Robinson Luce, the unique format relied on large oversize photos and minimal text. A staunch anti-Communist, W.A. Swanberg called Luce “the world’s most powerful unacknowledged political propagandist” (

Swanberg 1972, p. 141). Luce saw America’s entry into the New Frontier of space as the ultimate adventure story in which he could offer the perfect forum for its telling.

Life was one of the best-selling and most influential news sources in America (

Prendergast and Colvin 1986 p. 9). The popularity of the magazine did not go unnoticed by the Kennedy administration. David Halberstam wrote that Kennedy viewed

Life as a “key to the independent center”. The President saw the magazine during the pre-television era as “the most influential instrument in the country” (

Halberstam 1977, pp. 352–53).

Walter Bonney, NASA’s first public affairs chief, approached

Life with the idea of offering them an exclusive contract that would tell the astronauts’ story to eliminate the distraction caused by the astronauts seeking to compete with different publications for the most lucrative deal. NASA liked the idea, because it helped them control the coverage. The astronauts liked it because it was lucrative.

Life met the minimum bid and won the contract in August of 1959 (

Wainwright 1986, p. 261), a contract that would be renegotiated over subsequent years to include not only NASA’s first group of Mercury astronauts, but also others that were later selected to fly in the Gemini and Apollo programs. In total, the

Life contracts with NASA lasted eleven years, paying out millions to the astronauts and their wives, sixty people total (including eight widows), before the contracts ended beginning with Apollo 12, the second lunar landing mission (

Sherrod 1973, p. 24)”. NASA saw the contract with

Life as a perfect vehicle to help sell the nascent space program to the general public. Loudon Wainwright, who covered the Mercury Program and knew the astronauts well, wrote “as always, NASA needed public awareness and acceptance to keep its program going—and viewed favorably by Congress.

Life was a superb vehicle for that” (

Wainwright 1986, p. 263).

Life not only secured exclusive rights to the astronauts’ stories, but it also acquired book rights. In 1961, Life subcontracted with Golden Press and published The Astronauts: Pioneers in Space. The book appeared in multiple formats, including one written by Don A. Schanche that featured 48-gummed stamps depicting colorful photos from the Mercury Program that readers could stick on its pages.

Heavily illustrated with photos, graphics, and illustrations, these popular books were aimed at young readers. Wainwright’s book includes an opening chapter entitled “Seven Pioneers” and refers to space exploration as “an adventure more exciting and more far-reaching than anything man has done before” (

Wainwright 1961, p. 9). The sticker edition of the book ends with a chapter entitled “The Space Frontier” that optimistically proclaims that “Project Mercury will lead man to other great challenges of the space frontier” (

Schanche 1961, p. 48). These books show how the frontier narrative, along with patriotic journalism, served to help

Life depict the space program as a frontier adventure that appealed to all ages, while painting a portrait of a positive idealized America that helped reinforce President Kennedy’s New Frontier rhetoric.

During the post-war era, interest in science fiction grew, and inexpensive mass-produced paperbacks and pulp magazines emerged to meet the growing demand. Lines separating fiction from fact became less well defined as the New Frontier of space started to become a real place in popular culture. Nonfiction books began appearing that romanticized humanity’s future in space, with many of them borrowing the look and feel of popular pulps that had relied upon the formulaic elements of the classical frontier story.

As a result of the growing aerospace industry, trade publications emerged to help fill a need in the emerging scientific and engineering culture. Existing trade publications such as

Aviation Week adapted their original editorial content to meet the demand. In addition, new ones were created such as

Space World, edited by writer and publisher Ray Palmer, who served as editor of

Amazing Stories. In the October 1956 premiere issue of

Missiles and Rockets, the publisher wrote: “This is the age of astronautics. This is the beginning of the unfolding of the era of space flight. This is to be the most revealing and the most fascinating age since man first inhabited the earth” (

Parrish 1956, p. 5).

In

Another Science Fiction: Advertising the Space Race 1957–1962, Prelinger notes that advertising art in trade journals sometimes reflected a certain religious imagery that was most distinctly Christian in tone. “Most of the ad work that I interpret in my book is recruitment materials, and initially it was very fanciful and colorful. It was the type of art taken right from the pulp pages where contractors thought that anything was possible”, said Prelinger during an interview. “In studying the many trade publications containing this industrial art, my sense, and this is just a synthesis based upon my years of research, is that the artists largely had free rein,” said Prelinger. “The companies wanted imagery that would step outside of anything an engineer could come up with and get people’s attention and harness people’s engagement and faith in a company. It was predominantly… still is, but not as much, a Christian country at the time, and so I would guess that religious overtones reflecting that would appear in the artist’s work” (

Prelinger 2020). These images also convey the idea that we are being helped and guided so that success is inevitable.

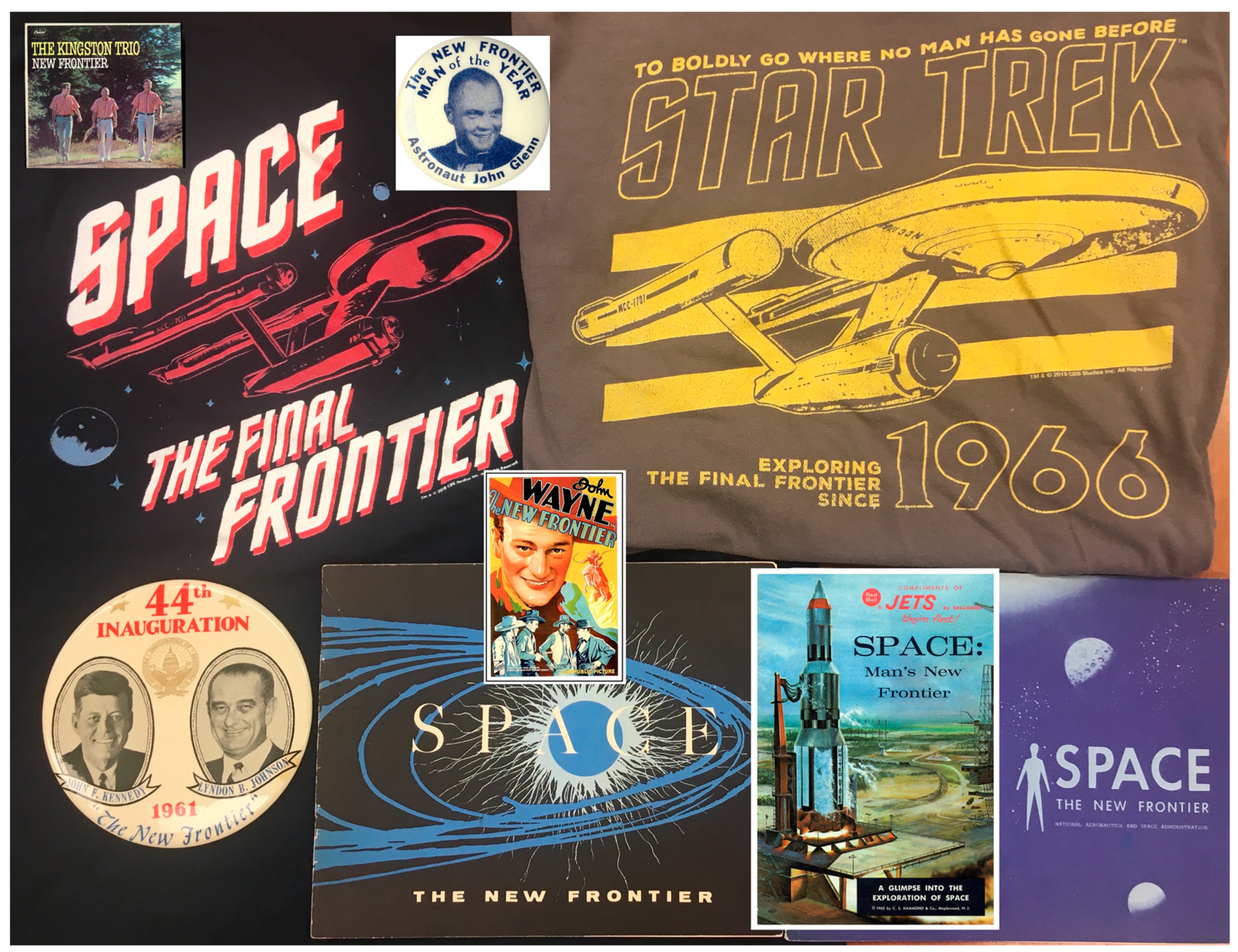

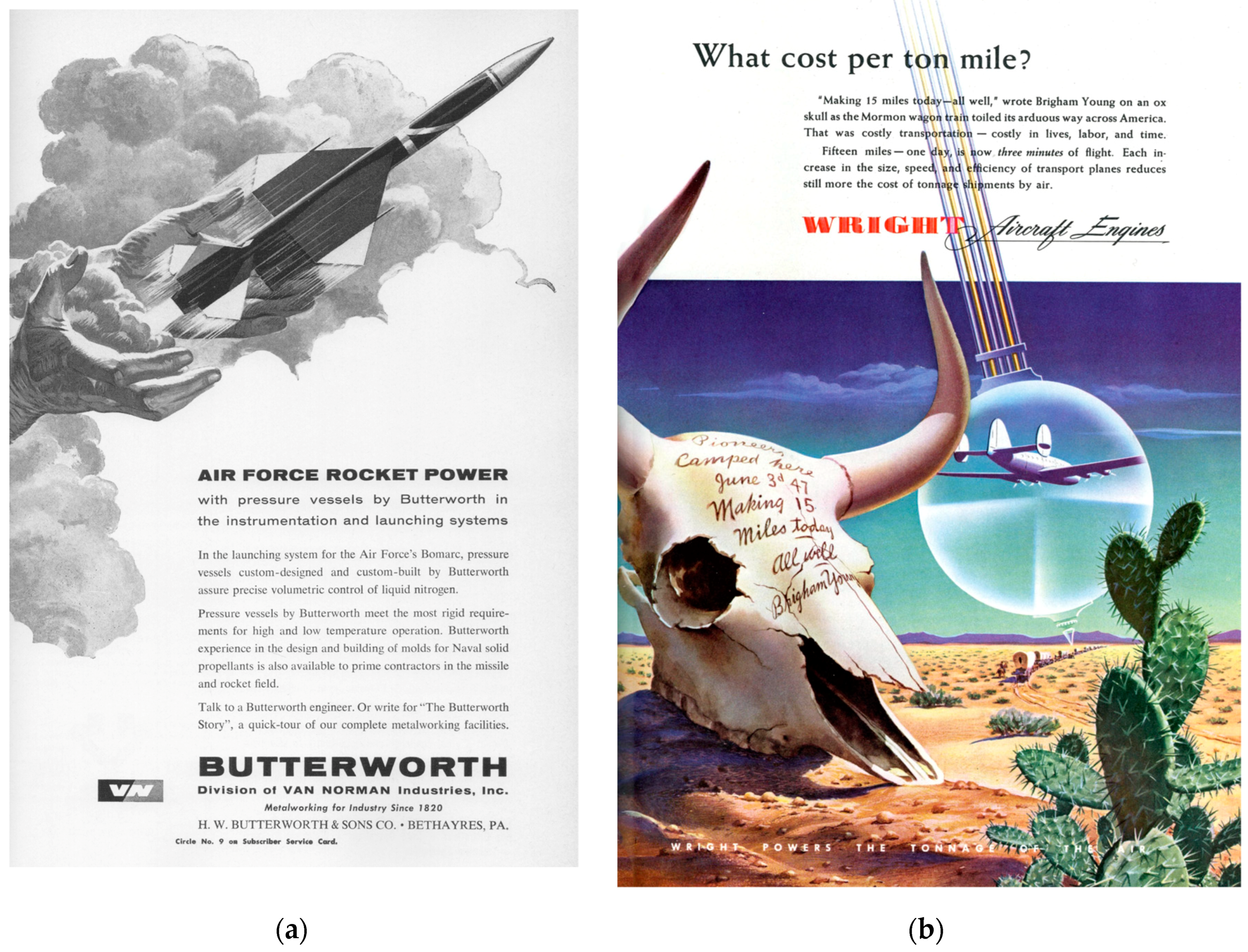

One advertisement (see

Figure 2) by Northrop used to promote its advanced engineering abilities loosely appropriates Michelango’s Sistine Chapel masterwork to illustrate its focus on the precision alignment needed to achieve space rendezvous (

Missiles and Rockets 1960). The gesture of reach, while calling to mind the disembodied hands of Jesus surrounded by heavenly clouds, is shown in another advertisement (see

Figure 3a) that features the US Air Force’s Bomarc missile (

Missiles and Rockets 1959).

In the March 1943 issue (Vol. 21, No. 3) of

National Aeronautics, the official publication of the National Aeronautic Association, there appears an advertisement for Wright Aircraft Engines. The advertisement shows a Lockheed Constellation flying overhead across the desert, while a caravan of horses and covered wagons follows below (see

Figure 3b). The plane is encapsulated in a large pendulum clock that conveys the passage of time. The advertisement begins with the question “What cost per ton mile”, followed by “’Pioneers Camped Here June 3d 47. Making 15 miles today—all well,’ wrote Brigham Young on an ox skull as the Mormon wagon train toiled its arduous way across America. That was costly transportation—costly in lives, labor, and time.” The advertisement continues with “Fifteen miles—one day, is now three minutes of flight. Each increase in the size, speed, and efficiency of transport planes reduces still more the cost of tonnage shipments by air.” The advertisement is an attempt to capture the hard slog of the various Mormon handcart expeditions, which were painfully slow and often deadly (Mormons did not use covered wagons). Wright Aircraft Engines may have been targeting Mormons for recruitment. “There was a mid-century push in intelligence to recruit Mormons on the assumption that because of their sobriety and family-centered nature they were ‘safer bets’. In addition to this, there is a strong tradition of Mormon hard science that goes back to the mid century” (

Bialecki 2020).

Neil Jacobe, who worked at McDonnell Douglas as an artist, explained that everything they did was directed by an art director and that artists had very little discretion in regards to the content of their compositions. They were also very busy, with many expected to complete 1–2 finished works a day (

Jacobe 2020). As to the implied religious imagery, some argue that it is not present. “The scenes involving enormous hands might just as easily be attributed to human hubris: that is, those images may represent the hands of Mankind rather than God”, said space artist Ron Miller (

Miller 2020).

Whether you interpret what you see in some of these ads as intentional religious imagery or not, it is worth noting that Robert McCall, one of the more famous space artists better known for his promotional artwork for Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and as a production illustrator for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), was a deeply religious man, and many of his works contain deliberate Christian symbolism, including pieces done as part of the NASA Art Program.

6. Other Media and the New Frontier

Over time, historians have distanced themselves from Frederick Jackson Turner’s thesis, arguing that it is too ethnocentric and nationalistic in its portrayal of the frontier as the locus of all American history and culture. Nevertheless, the myth of the western frontier still holds a powerful grip on American consciousness, as evidenced by the many books, movies, and television shows about the West that became wildly popular in the twentieth century. “The frontier”, Turner explains, “is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization” (

Turner 1998).

By the middle of the twentieth century, many Americans searched for a New Frontier, and some found it through television while watching a brand new science fiction series called

Star Trek (see

Figure 1). The civil unrest of the 1950s and 60s helped instill a belief in many Americans that space was not just a source for aliens bent on subjugating Earth’s populace, but a place that could be populated by average folks who warp through space aboard the starship

Enterprise, a faster-than-light spacecraft as big as an aircraft carrier and filled with a crew comprised not only of humans but other races from our galaxy.

Created by Gene Roddenberry, a former World War II bomber and commercial airline pilot from Texas who moved to Los Angeles after the War, the idea for Star Trek came while he worked as a police officer by day and a writer for television by night, where he wrote mainly police stories and westerns. Eventually, studios gave him a shot at producing his own television shows.

Though initially not a big fan of science fiction, Roddenberry was caught up in the enthusiasm generated by President Kennedy’s New Frontier campaign. He recognized that the time might be right for a serious science fiction show that would address some of the social problems that otherwise might be too sensitive to tackle if portrayed in other television genres.

In 1964, Roddenberry began filming Star Trek’s first pilot “The Cage”. When shown to network executives, they thought that it would be “too cerebral” for mainstream viewers. However, they were willing to give the young television producer another chance, so they ordered a second pilot. This proved to be the charm, and Star Trek premiered on NBC on Thursday nights beginning 8 September 1966.

Each week, the show’s introductory monologue began with the voice of Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) announcing “space… the final frontier”, inviting viewers to join the crew of the starship Enterprise where they witnessed Roddenberry’s vision of life in the 23rd century. Through Star Trek, Roddenberry sought to invoke the same frontier nostalgia that was seen in the many Westerns that competed for television viewers every week. Like the American frontier that allowed a belief in rugged individualism that would lead to a better life during the nineteenth century, Star Trek allowed Americans to believe that the New Frontier of space represented a better tomorrow. This optimism was one of the key factors in the show’s popularity, in addition to its ability to maintain a Western theme by reinventing the frontier spirit to celebrate the space cowboy that so appealed to western democracies.

In addition to television, the inspired optimism of the Space Age and the emerging interest and excitement from exploring the New Frontier of space influenced music as well. After the Second World War, examples of “science-fictional” or “space age pop” music began to emerge. This type of music varied in style, rhythm, and arrangement, but shared a common similarity characterized by generous uses of string orchestra (or simulated strings) combined with a Latin American Music percussion section. The keyboard, both traditional and later electronic, is also frequently used, as well as the theremin, which produces an eerie off-world sound that became the trademark of many early science fiction movie soundtracks.

Collectively, these “sounds” of the New Frontier offered a forum that served to revive the mythical images of those who conquered the Western frontier. Tunes used by wagon teams who traveled west along the Oregon Trail to a new life served as inspiration for songs that would inspire a new generation of explorers wishing to travel into space. One of the best examples of this is Walter Schumann’s 1955 concept album,

Exploring the Unknown. In this album, Schumann teamed with fellow composer Leith Stevens, who wrote music for such notable science fiction classics as

Destination Moon (1950),

When Worlds Collide (1951), and

The War of the Worlds (1953). In

Exploring the Unknown, Schumann and Stevens combine their talents to create a space-pop fantasia that rockets listeners through a celestial voyage. Beginning with a rocket launch from the Pacific, listeners travel beyond the Moon to arrive at Venus, where they encounter aliens. From here, they travel out into the universe before returning safely back to Earth, all the while accompanied by a background of heavy orchestration, celestial vocals, and a steady narration by veteran voice actor Paul Frees (

Schumann 1955a).

Launched just a few years before Sputnik in 1955,

Exploring the Unknown’s New Frontier theme is very much apparent throughout the album. Its first song, entitled

New Frontiers (

Schumann 1955b), is a march that conjures up images of America’s ancestors sailing west across the Atlantic. Even though the song is meant to invoke the New Frontier of space, it is hard not to picture brave pioneers crossing the Atlantic in a “sea of mystery” to “blaze a trail through the long light years” in an effort to meet any “wonders face to face” that “challenges the human race” to conquer the land of the New World to make “the universe one”. This pioneering is sanctioned by God in the album’s final song

Look Up (

Schumann 1955c). Here, the song’s lyrics explain how the bold pioneers of this New Frontier of space have faith in what they are doing “beyond the fading Sun” as there is “Light enough that’s bright enough” to keep their “faith” in “the hand divine” that is “commanding all” to remind “us just how small we are”. Humility along, with divine affirmation that what you are doing is God’s will, all make for a successful frontier narrative. The album conveys a very powerful message that the New Frontier of outer space is the frontier of America and is ready for the taking with God at their back (

Schumann 1955a). The message of this album reaffirms what Newell describes as “the sense of chosenness by God that antedated the exceptionalism of the nineteenth century and could now be subsumed into the space boosterism of the twentieth century as a kind of revitalization of an American brand of utopianism and as a powerful belief in the efficacy of progress” (

Newell 2019, pp. 228–9).

With the launch of Sputnik, the number of record albums of this type increased. However, the bulk of them were traditional LPs containing collections of songs composed with a Space Age theme. Exploring the Unknown was a concept album, so why was it produced and what was its intended audience? One possible answer might be found in Walt Disney and Collier’s Magazine.

To help promote Disney’s new theme park and its five original themed “lands” of Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, Main Street USA, and Tomorrowland, Walt Disney premiered “Disneyland”, a network television show that first aired on CBS in 1955, the same year the park opened. Shows tied to the themes of Disney’s theme park were presented each week and introduced by Walt Disney himself. To help promote Tomorrowland, Disney created a three-part series about space. The first episode, entitled

Man in Space, premiered on 9 March 1955. This was followed later that year with

Man and the Moon and finally

Mars and Beyond that showed in 1957. These three films helped introduce Americans to the idea of the New Frontier of outer space. Episodes included guest appearances by such rocket scientists as Willy Ley, Heinz Haber, and Wernher von Braun.

Exploring the Unknown narrator Paul Frees, known as “The Man of a Thousand Voices”, did work for Disney including

Man in Space and

Mars and Beyond (

Reinehr and Swartz 2008, p. 104).

More than one hundred million Americans saw

Man in Space, approximately 60 percent of the US population at that time (

Ordway et al. 1992, p. 145). Praised by critics for their high quality production values, these Disney films preached the gospel of spaceflight to Americans, many of whom were already primed after reading the

Collier’s series on space. From 22 March 1952, to 30 April 1954,

Collier’s magazine published a series of eight articles that laid forth America’s future in space. These were written by a panel of experts that included Wernher von Braun, Fred L. Whipple, Joseph Kaplan, Heinz Haber, and Willy Ley. The

Collier’s series gave a realistic blueprint for space exploration accompanied by breathtaking artwork done by Chesley Bonestell, Fred Freeman, and Rolf Klep.

With the 1952

Collier’s series, followed three years later with the opening of Tomorrowland and the premiere of the three-part “Disneyland” television series on space, public perception toward spaceflight began to change. In late 1949, George Gallup conducted a poll asking the public what their envisioned expectations by the year 2000 would be for science and technology. Eighty-eight percent thought we would find a cure for cancer. Sixty-three percent thought we would have atomic trains and airplanes. Only fifteen percent thought man would land on the Moon. Less than six years later, that same Gallup poll resulted in thirty-eight percent thinking that space travel was possible by the end of the twentieth century (

Neufeld 2008, p. 277). By 1955, there emerged a belief among the youth in America’s households that human space travel was not only something that could be done in their parent’s lifetime, it was also becoming hip, and record albums like

Exploring the Unknown fit right in with a public clamoring to learn more about the possibilities of the New Frontier of space.

7. Conclusions

The American space program emerged as a democratic challenge to the threat of communist supremacy in the arena of outer space, and by default, that response carried a religious tone as a counterpart to the Soviet Union and its official atheistic stance. As anthropologist Deana Weibel writes, “The United States is a country, then, that sees itself, at least in terms of its historical mythology, as following the dictates of God and being rewarded in these pursuits. Space exploration has been an area of particular American achievement and many within the space program, particularly during the Space Race, believed that God’s blessing was what made American success in space possible” (

Weibel 2020).

National space rhetoric has played an integral part in the narrative of human spaceflight in America. NASA, members of Congress, and presidents from John F. Kennedy to the current administration all have embraced its sustained ideology of exceptionalism and long-standing beliefs in progress of the New Frontier with its associated images of pioneering individualism and rugged free enterprise. Even though the political, social, economic, and cultural context for space exploration has changed since the last footprints were left on the Moon, administrations continue to use this same rhetoric to help sell their vision for space.

In 1986, President Reagan’s National Commission on Space, which was appointed to develop long-term goals for US civilian space exploration, entitled its final report

Pioneering the Space Frontier. In this report, it describes its “pioneering mission for 21st-century America: to lead the exploration and development of the space frontier” (

National Commission on Space 1986, pp. 2–3). In its 90-day

Study on the Human Exploration Initiative, NASA declared, “the imperative to explore is embedded in our history… traditions, and national character”, and space is “the frontier” to be explored (

NASA 1989, pp. 1, 104).

This theme continued during the George H.W. Bush administration: “America’s space program is what civilization needs… America, with its tremendous resources, is uniquely qualified for leadership in space… our success will be guaranteed by the American spirit—that same spirit that tamed the North American continent and built enduring democracy.” The “prime objective” of the US space program is “to open the space frontier” (

National Space Council 1990, p. 17). Still another space study group during this time stated that “space is the new frontier”, where the United States would find “a future of peace, strength, and prosperity” (

Synthesis Group 1991, pp. iv, 9, 14).

Under the George W. Bush Administration, NASA Administrator Michael Griffin said that the aim of space exploration is “to make the expansion and development of the space frontier an integral part of what it is that human societies do” (

Billings 2007, p. 494). Griffin has said, “it is in the nature of humans to find, to define, to explore and to push back the frontier. And in our time, the frontier is space and will be for a very long time… The nations that are preeminent in their time are those nations that dominate the frontiers of their time. The failed societies are the ones that pull back from the frontier. I want our society, America, [W]estern society to be preeminent in the world of the future and I want us not be a failed society. And the way to do that, universally so, is to push the frontier” (

Harwood 2006).

In a video designed to recruit volunteers to join the newest branch of the US military, the Space Force makes use of extensive language and imagery that are heavily influenced by ideas of the frontier-crossing and religious destiny. Using scenes of a contemplative young man standing along the seashore looking up to the heavens, the “Age of Exploration” is invoked, a time when Europeans traveled the globe in search of adventure, excitement, resources, and goods all the while spreading their influence while gaining strength and power under the guise of colonialism.

As the camera cuts to new recruits looking at a towering rocket before them, the video shows quick takes of an ethnic mix of Space Force members doing different jobs. As the video comes to a close, the narration takes on a somewhat religious tone. “Maybe,” the voice suggests, “you weren’t put here just to ask the questions. Maybe you were put here to be the answer. Maybe your purpose on this planet isn’t on this planet.” Here, the listener is presented with philosophical or even metaphysical language. From the implication that you were “put” here suggests that there was something that did the putting. The terms “purpose”, “questions”, and “answer” all suggest a guiding authority: if you join the Space Force, you will find meaning in life (

Weibel 2020). The last phrase suggests that the listener’s destiny might not be on this world, but off it. If you join the Space Force, you may not only travel into space, but perhaps even to another planet. Though not religious itself, this suggests that the Space Force cadets or whatever they are going to be called may help fulfill a special destiny, perhaps not only for themselves, but for whomever or whatever else they may find along the way.

The rhetorical usage of a higher power in this promotional video reflects a general ascendancy of religious conservatives in the political sphere and their desire to connect with this voting group—particularly the Republican Party. When John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, there was concern that he and his administration would be a Vatican tool, because he was a Catholic. Over half a century since that time, the dynamics of religion in American politics have changed. Religious conservatives have taken on a greater ascendency in US politics.

Kevin Cole and David Domke analyzed presidents’ Inaugural and State of the Union addresses, beginning with Franklin Roosevelt in 1933. What they were looking for was the presence of “God talk” and any emphasis on freedom and liberty, two principles of great importance to religious conservatives. What they found is that the Reagan presidency was a watershed moment for American presidential religious discourse. “Beginning with Reagan, presidents have employed more God talk and have more frequently emphasized freedom and liberty in their State of the Union and Inaugural addresses than have previous modern presidents” (

Cole and Domke 2006, p. 317). Cole and Domke point out that whereas their Cold War counterparts placed similar emphasis on freedom and liberty, Reagan and Bush had a “greater propensity to claim that a divine being has a special connection with freedom and liberty, and their much greater likelihood to speak declaratively about God’s wishes for these principles” (

Cole and Domke 2006, p. 323).

Even though the Cole and Domke study concludes with president George W. Bush, the contemporary political climate of today reveals that a religious and political nexus is still present even in the New Frontier rhetoric of space. Vice President Pence during the Trump administration has generated attention, not so much for supporting the US space program, but in how he goes about doing it. Marina Koren has written about Pence’s frequent use of religious language when talking about space, particularly the Space Force. She writes that, “when Pence speaks of space exploration, he speaks not only of the frontier, but of faith. His speeches sometimes sound more like sermons,” and cites a statement Pence made at the very first meeting of the National Space Council in 2017: “As President Trump has said, in his words, “It is America’s destiny to be the leader amongst nations on our adventure into the great unknown. And today we begin the latest chapter of that adventure. But as we embark, let us have faith. Faith that, as the Old Book teaches us, that if we rise to the heavens, He will be there” (

Koren 2018).

Since the end of the Cold War, New Frontier rhetoric has continued to dominate official and public discourse among space advocacy groups. Patricia Nelson Limerick notes that space advocates especially embrace the New Frontier metaphor, because they conceive “American history [as] a straight line, a vector of inevitability and manifest destiny linking the westward expansion of Anglo-Americans directly to the exploration and colonization of space” (

Limerick 1994, p. 13). William E. Burrows describes how the space advocate community heavily promotes spaceflight, because “at the heart of it all, as usual, [are] the core dreamers… who steadfastly believed it was their race’s manifest destiny to leave Earth for both adventure and survival” (

Burrows 1998, p. 507).

According to Linda Billings, the metaphor of the New Frontier with all of its associated images of manifest destiny, great courage, steadfast resolve, Puritan work ethic, and pioneering spirit looms large in a belief system that is still perpetuated by Americans whose ideology rests on a number of assumptions about the role the US has played in the global community. Billings asserts that the rhetoric of frontier conquest and exploitation and its accompanying ideology that the US must remain “number one” by playing the role of political, economic, scientific, technological, and moral leader may be appealing to a certain demographic, but it is not one that is globally shared (

Billings 2015, p. 12). Other nations, such as the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency with its “explore to realize” slogan, have taken a more pragmatic approach in formulating their plans for space that are less ideological.

Perhaps it is time to reexamine our nation’s space rhetoric whose words may no longer have the same meaning they once did at the height of the Cold War. Jacques Blamont, the founding director of the French Space Agency CNES, argues that people are losing interest in the human exploration of space “because spacefaring nations, and especially the USA, have clung to outmoded cold war ways of thinking about it. The US attitude of ‘command’ over its international partners will no longer work” (

Billings 2015, p. 12).

Here on Earth, manifest destiny originated as an explicitly religious concept, so it does not take a leap of faith to see how that same religiosity was carried forward into the New Frontier of space. The idea that a human future in space is written in the stars is compelling. “For many involved in the American project of human space settlement, a belief in destiny is a powerful source of motivation that often shapes and is shaped by religious ideas, and, even in the absence of explicit beliefs, inspires a secular sort of faith,” writes Deana Weibel, a professor of anthropology and religious studies at GVSU who has interviewed numerous scientists, astronauts, and workers in the space field. She found that “a sense of destiny—religious or otherwise—provides many contemporary space workers, from astronauts and astronomers to engineers and aerospace physicians, with the moods and motivations humanity will need if we are ever to become a multi-planet species” (

Weibel 2019).