A New Lens for Seeing: A Suggestion for Analyzing Religious Belief and Belonging among Emerging Adults through a Constructive-Developmental Lens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Trends on Religious Belief and Belonging among Emerging Adults

The example reveals that Overstreet’s analysis goes beyond taking the student’s words at face value. Instead, she takes into account the interior processing of the individual and their cognitive development as college students.The students’ reflections on their religious and spiritual beliefs and practices often conveyed a longing for independence and autonomy (e.g., not going to church because your parents tell you [Molly], disagreeing with your parents so they know you have developed your own beliefs [Justin]).

3. Recognizing the Cognitive Development of Emerging Adults

3.1. Seeing through the Cognitive-Developmental Lens

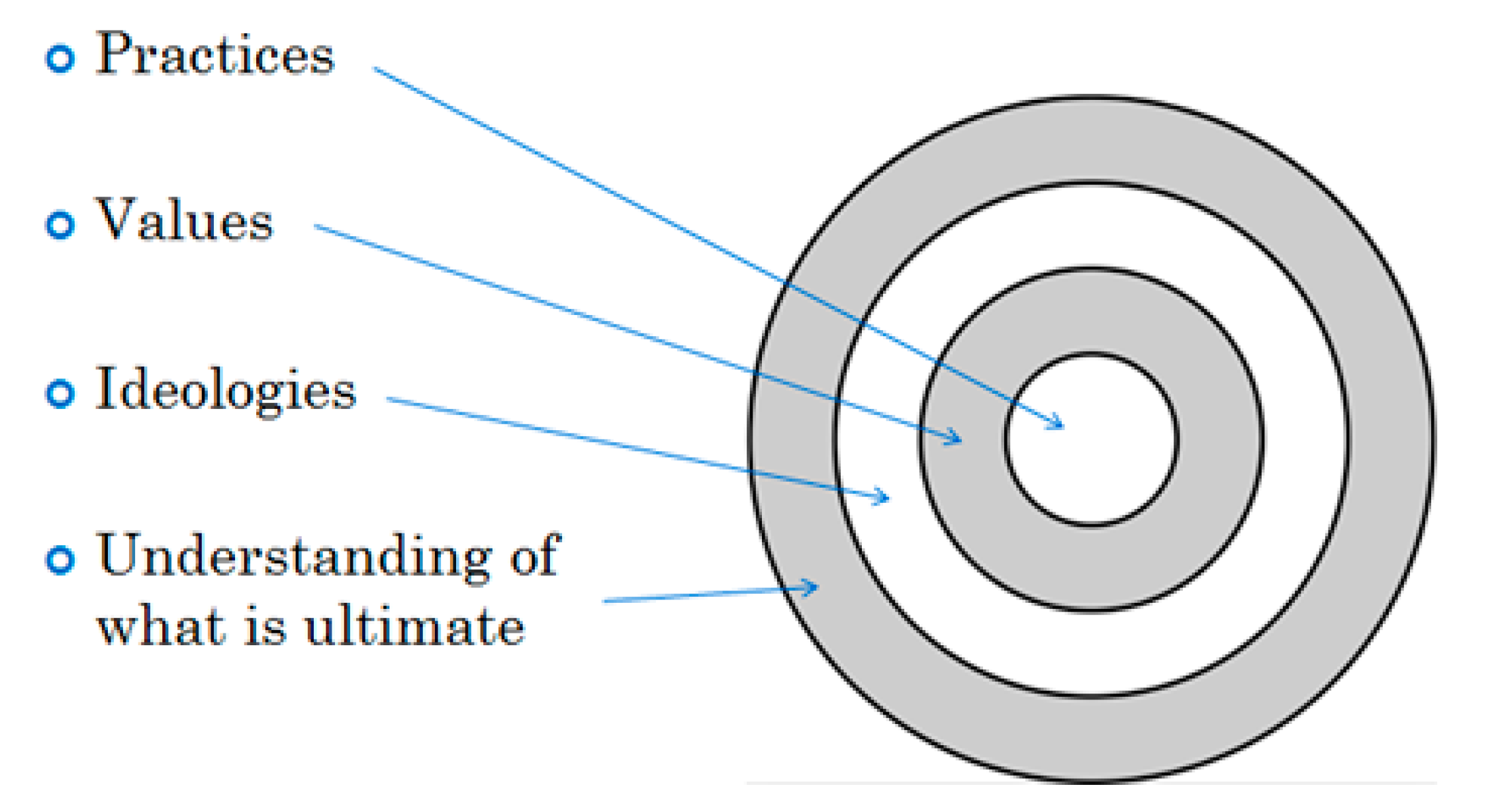

3.2. Translating the Constructive-Developmental Lens to Religious Setting

4. Reading through the Constructive-Developmental Lens

4.1. Seeing beyond the Concrete, But…

But in reality, kids go to church because they think that is what kids do, they don’t realize they have a choice.

It was not until I went to college that I was officially out of the Catholic Church. I was no longer forced to be Catholic. When this finally happened I was relieved and happy, really now I was able to make my own decisions. I have never went back to church.

In each of these, we notice that she not only names choice, but can apply it to multiple situations, reflecting a capacity to work with choice as a value. Yet, we should also notice that her lack of freedom did not come from religious injunctions, but from parental restrictions. While still limited in some ways to the self-referential concern of the second-order knower, her statements indicate that she is gaining the capacity for formal operational thought, a necessary precursor for third-order knowing.I went to Catholic schools from kindergarten through high school. That was something that I did not have a choice in either.

4.2. Authority and the Possibility of Choice

The interview transcript indicates that Edward can think in terms of allegiances and that different communities have different ways of seeing things. A “face value” reading of the interview assumes that Edward’s perception of science and Catholicism is accurate and his decision to disaffiliate well founded. What remains unexamined in the interview is determining with more clarity on what his decision is based.I always have been very smart and I was always studious. But as I started to enjoy math and science more I just realized the discrepancy between science and religion. I guess that was another shaking point. Obviously the two can coexist fairly easily, people do it all the time, but for me I was one of those more toward the science end of things. Catholicism, especially, did seem to clash fairly well…. That pushed me away from the Church a bit more because of the belief in science that really didn’t stack up with religion as far as agreeing with each other.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2004. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, Tom. 2013. Theological Roundtable on Deconversion and Disaffiliation in Contemporary US Roman Catholicism. Horizons 40: 255–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoin, Tom, and J. Patrick Hornbeck II. 2013. Deconversion and Ordinary Theology: A Catholic Study. In Exploring Ordinary Theology: Everyday Christian Believing and the Church. Edited by Jeff Astley and Leslie J. Francis. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Bergler, Thomas. 2005. Book Review Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Christian Education Journal 2: 451–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Uri. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Uri. 2005. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Byron, William J., and Charles Zech. 2012. Why They Left. America Magazine. April 30. Available online: http://americamagazine.org/issue/5138/article/why-they-left (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Chan, Melissa, Kim M. Tsai, and Andrew J. Fuligni. 2015. Changes in Religiosity across the Transition to Young Adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 44: 1555–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalessandro, Cristen. 2016. “I don’t advertise the fact that I’m a Catholic”: College students, religion, and ambivalence. Sociological Spectrum 36: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, Cary, and Greg Smith. 2012. “Nones” on the Rise: One-in-Five Adults Have No Religious Affiliation. Washington: Pew Research Center, Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise/ (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Kegan, Robert. 1982. The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, Robert. 1994. In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin, Barry A., and Ariela Keysar. 2013. Religious, Spiritual, and Secular: The Emergence of Three Distinct Worldviews among American College Students. A Report Based on the ARIS 2013 National College Student Survey. Hartford: Trinity College. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey, Lisa, Emily Souvaine, Robert Kegan, Robert Goodman, and Sally Felix. 2011. A Guide to the Subject-Object Interview: Its Administration and Interpretation. Cambridge: Minds at Work. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1984. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, Robert, and John Vitek. 2018. Going, Going, Gone: The Dynamics of Disaffiliation in Young Catholic. Winona: St. Mary’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe, Theresa A. 2018. Navigating toward Adulthood: A Theology of Ministry with Adolescents. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet, Dawn V. 2010. Spiritual vs. Religious: Perspectives from Today’s Undergraduate Catholics. Catholic Education: Journal of Inquiry and Practice 14: 238–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Packard, Josh, and Ashleigh Hope. 2015. Church Refugees: Sociologists Reveal Why People Are DONE with Church but not Their Faith. Loveland: Group Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian, and Patricia Snell. 2009. Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian, Kyle Longest, Jonathan Hill, and Kari Christoffersen. 2013. Young Catholic America: Emerging Adults In, Out of, and Gone from the Church. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Streib, Heinz, Ralph W. Hood Jr., Keller Barbara, F. Silver Christopher, Csoeff Rosina-Martha, and T. Richardson James. 2009. Deconversion: Qualitative and Quantitative Results from Cross-Cultural Research in Germany and the United States of America. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 1989. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, Angie, and Casper ter Kuile. 2012. How We Gather. Cambridge: Harvard Divinity School, Available online: https://www.howwegather.org/reports (accessed on 21 August 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Keefe, T.A.; Jendzejec, E. A New Lens for Seeing: A Suggestion for Analyzing Religious Belief and Belonging among Emerging Adults through a Constructive-Developmental Lens. Religions 2020, 11, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110573

O’Keefe TA, Jendzejec E. A New Lens for Seeing: A Suggestion for Analyzing Religious Belief and Belonging among Emerging Adults through a Constructive-Developmental Lens. Religions. 2020; 11(11):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110573

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Keefe, Theresa A., and Emily Jendzejec. 2020. "A New Lens for Seeing: A Suggestion for Analyzing Religious Belief and Belonging among Emerging Adults through a Constructive-Developmental Lens" Religions 11, no. 11: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110573

APA StyleO’Keefe, T. A., & Jendzejec, E. (2020). A New Lens for Seeing: A Suggestion for Analyzing Religious Belief and Belonging among Emerging Adults through a Constructive-Developmental Lens. Religions, 11(11), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110573