How is Military Chaplaincy in Europe Portrayed in European Scientific Journal Articles between 2000 and 2019? A Multidisciplinary Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Military Chaplaincy in Changing Contexts

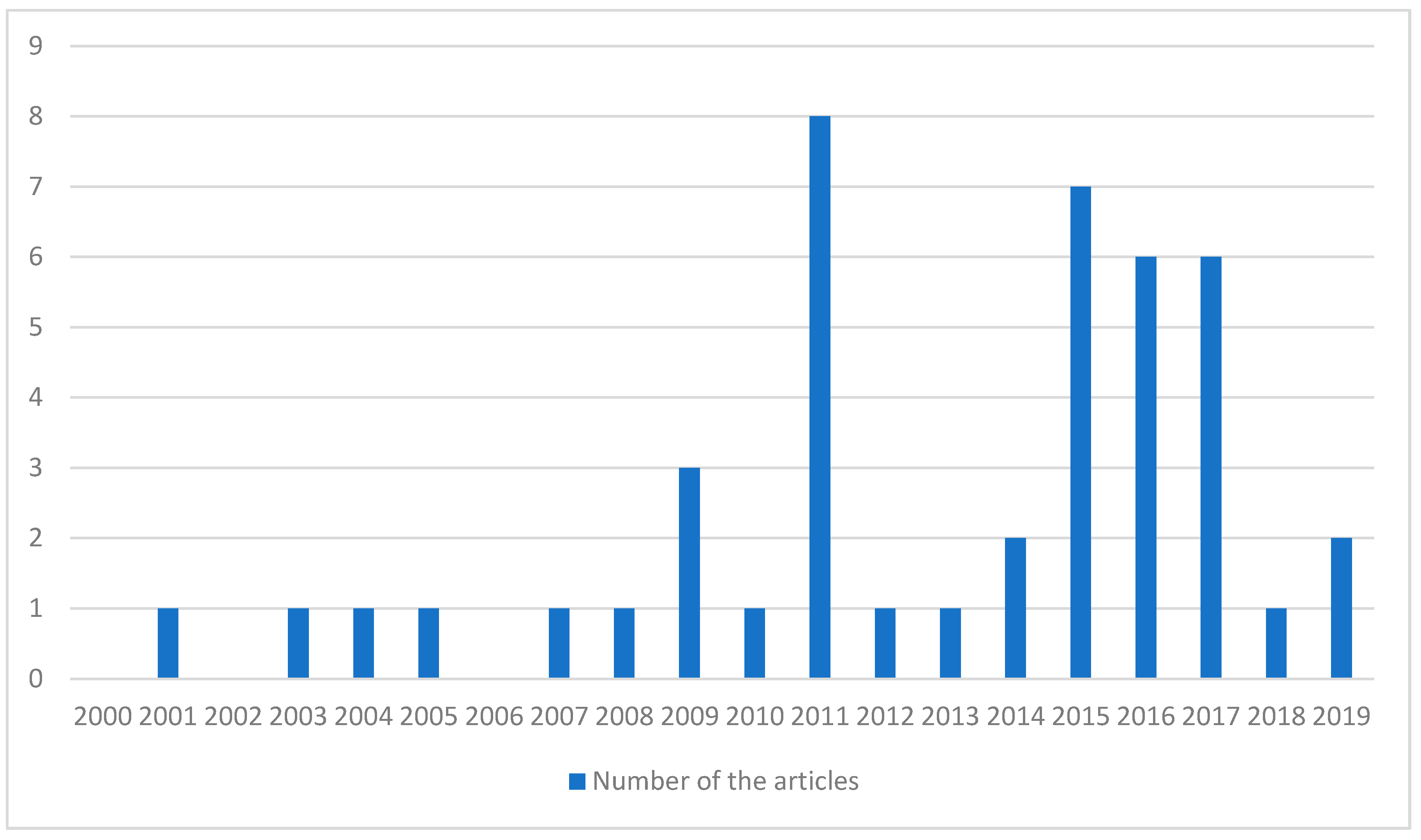

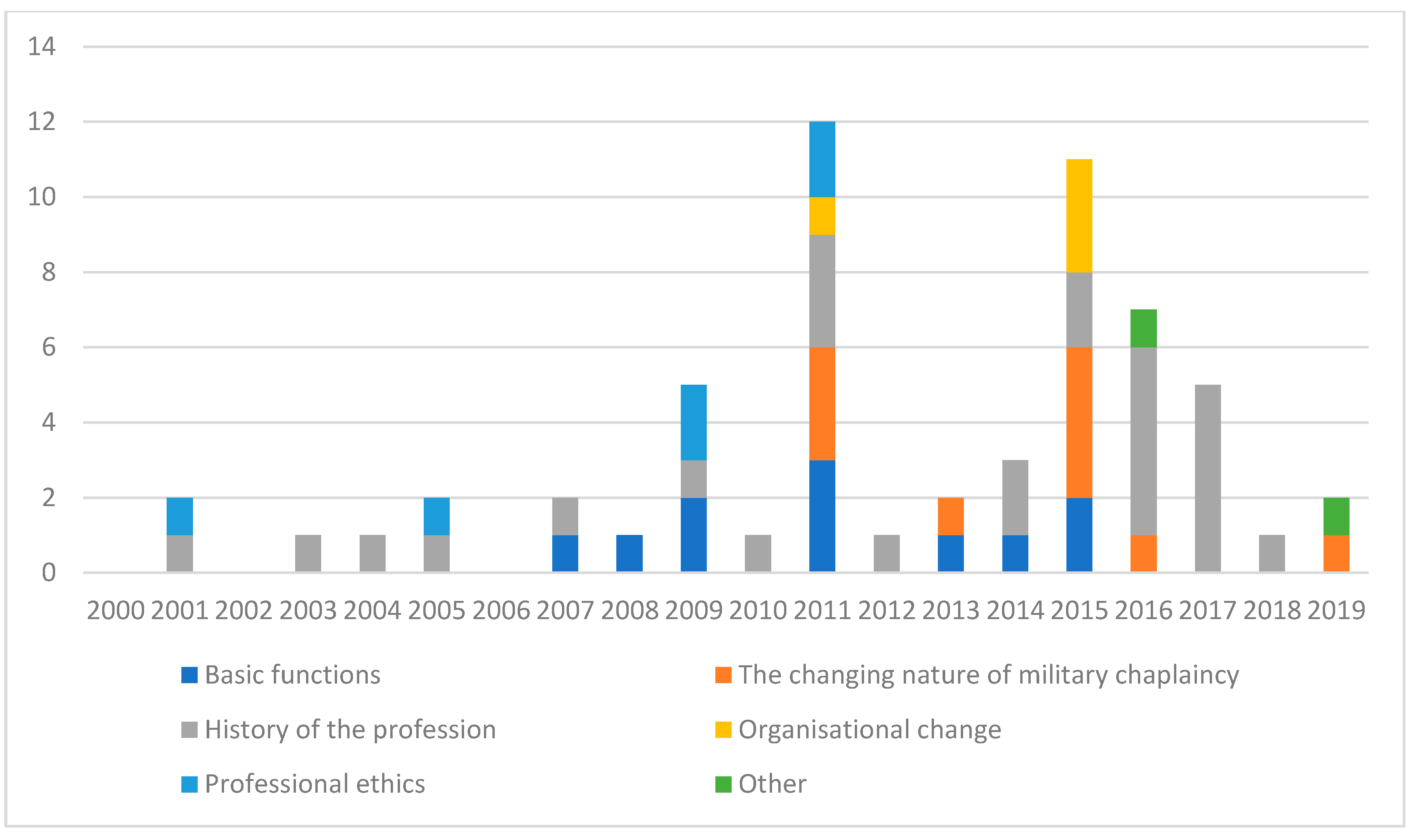

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Themes in the Selected Articles

3.2. Basic Functions

3.3. The Changing Nature of Military Chaplaincy

3.4. History of Profession

3.5. Organisational Change

3.6. Professional Ethics

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Article | Basic Functions | Changing Nature of Military Chaplaincy | History of the Profession | Organisational Change | Professional Ethics | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2001 | German Military Chaplains in World War II and the Dilemmas of Legitimacy. Bergen, Doris L. Church history 70, no. 2 (June 1, 2001): 232–247. | X | X | ||||

| 2 | 2003 | The Organisation of Military Religion in the Armies of King Edward I of England (1272–1307). Bachrach, David S. Journal of medieval history 29, no. 4 (2003): 265–286. | X | |||||

| 3 | 2004 | The Friars Go to War: Mendicant Military Chaplains, 1216-c. 1300. 54. Bachrach. David S. The Catholic historical review 90, no. 4 (October 1, 2004): 617–633. | X | |||||

| 4 | 2005 | Beyond Comfort: German and English Military Chaplains and the Memory of the Great War, 1919–1929. Porter, Patrick. Journal of religious history 29, no. 3 (October 2005): 258–289. | X | X | ||||

| 5 | 2007 | Deaths Among Army Chaplains, 1939–1946. Howson, P. 2007. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 85, no. 342 (2007): 162–172. | X | X | ||||

| 6 | 2008 | Military Chaplaincy in International Operations: A Comparison of Two Different Traditions. Barker, C. R. & Werkner, I-J. 2008. Journal of Contemporary Religion 23, no. 1 (2008): 47–62 | X | X | ||||

| 7 | 2009 | Death in the armed forces: casualty notification and bereavement support in the UK military. Cawkill, P. 2009. Bereavement Care 28, no. 2 (2009): 25–30. | X | |||||

| 8 | 2009 | The military career of Bishop Robert Brindle. Hagerty, J. 2009. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 87, no. 350 (2009): 123–127. | X | |||||

| 9 | 2009 | Reflecting Ethically with British Army Chaplains. Todd, A 2009. The Review of Faith & International Affairs 7, no. 4 (2009): 77–82. | X | X | ||||

| 10 | 2010 | Against Bolshevism: Georg Werthmann and the Role of Ideology in the Catholic Military Chaplaincy, 1939–1945. Faulkner, L. N. 2010. Contemporary European History 19, no. 1 (2010): 1–16. | X | |||||

| 11 | 2011 | Military Chaplains and the Religion of War in Ottonian Germany, 919–1024. Bachrach, David. 2011. Religion, State and Society 39, no. 1 (2011): 13–31. | X | X | ||||

| 12 | 2011 | The Changing Role of Military Chaplaincy in Germany: from Raising Military Morale to Praying for Peace. Dörfler-Dierken, A. 2011. Religion, State and Society 39, no. 1 (2011): 79–91. | X | X | X | |||

| 13 | 2011 | Changing Chaplaincy: A Contribution to Debate over the Roles of US and British Military Chaplains in Afghanistan. Gutkowski, S. & Wilkes, G. 2011. Religion, State and Society 39, no. 1 (2011): 111–124. | X | |||||

| 14 | 2011 | ‘Command and Control’ in the Royal Army Chaplains’ Department: how Changes in the Method of Selecting the Chaplain General of the British Army Have Altered the Relationship of the Churches and the Army. Howson, P. 2011. Religion, State and Society 39, no. 1 (2011): 63–78. | X | X | ||||

| 15 | 2011 | Military careers and Buddhist ethics. Kariyakarawana, S. 2011. The International Journal of Leadership in Public Services 7, no. 2 (2011): 99–108. | X | X | X | |||

| 16 | 2011 | Orthodox concordat? Church and state under Medvedev. Papkova, I. 2011. Nationalities Papers 39, no. 5 (2011): 667–683. | ||||||

| 17 | 2011 | Catholic Chaplains to the British Forces in the First World War. Rafferty, O. 2011. Religion, State and Society 39, no. 1 (2011): 33–62. | X | |||||

| 18 | 2011 | Church of England Army Chaplains in the First World War: Goodbye to ‘Goodbye to All That’. Snape, M. 2011. The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 62, no. 2 (2011): 318–345. | ||||||

| 19 | 2012 | Imperial Frameworks of Religion: Catholic Military Chaplains of Germany and Austria-Hungary During the First World War. Houlihan, P. 2012. First World War Studies 3, no. 2 (2012): 165–182. | X | |||||

| 20 | 2013 | Bereavement support in the UK Armed Forces: The role of the Army chaplain. Cawkill, Paul & Smith, R. 2013. Bereavement Care 32, no. 1 (2013): 11–15. | X | X | ||||

| 21 | 2014 | Jewish Military Chaplains in the Austro-Hungarian Armed Forces During World War I. Bíró, Ákos. 2014. Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 59, no. 2 (2014): 397–406. | X | |||||

| 22 | 2014 | The Consolation of Soldiers: religious life in the Swedish army during the Great Northern War. Gudmundsson, D. 2014. Scandinavian Journal of History 2014: 1–14. | X | X | ||||

| 23 | 2015 | The military chaplain: a study in ambiguity. Davie, Grace. 2015. International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church 15, no. 1 (2015): 39–53. | X | X | ||||

| 24 | 2015 | Muslim chaplaincy in the UK: the chaplaincy approach as a way to a modern imamate. Hafiz, A. 2015. Religion, State & Society 43, no. 1 (2015): 85–99. | X | X | X | |||

| 25 | 2015 | The Muslim Military Clergy of the Russian Empire at the End of the XVIIIth - Beginning of the XXth Century. Khayrutdinov, R. & Abdullin, K. 2015. Journal of Sustainable Development 8, no. 7 (2015): 121. | X | |||||

| 26 | 2015 | What is at stake when Muslims join the ranks? An international comparison of military chaplaincy. Michalowski, I. 2015. Religion, State & Society 2015: 1–18. | X | |||||

| 27 | 2015 | ‘Newcomer religions’ as an organisational challenge: recognition of Islam in the Austrian armed forces. Krainz, U. 2015. Religion, State & Society 2015: 1–14. | X | X | ||||

| 28 | 2015 | ‘You’re in the army now!’ Institutionalising Islam in the Republic’s Army. Settoul, E. 2015. Religion, State & Society 2015: 1-12. | X | X | ||||

| 29 | 2015 | Muslim soldiers, Muslim chaplains: the accommodation of Islam in Western militaries. Stoeckl, K. & Roy, O. 2015. Religion, State & Society 43, no. 1 (2015): 35–40. | X | |||||

| 30 | 2016 | A Free Church Perspective on Military Chaplains Role in Its Historical Context. Allison, Neil E. 2016. In die skriflig: tydskrif van die Gereformeerde Teologiese Vereniging 50, no. 1 (March 18, 2016): 1–e8. | X | X | ||||

| 31 | 2016 | Irish Jesuit Chaplains in the First World War. Lavenia, Vincenzo. 2016. Edited by Damien Burke. Journal of Jesuit Studies 3, no. 1 (January 2016): 162–164. | X | |||||

| 32 | 2016 | ‘Der König rief, und alle, alle kamen’ Jewish military chaplains on duty in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. Hecht, D. J. Jewish Culture and History 2016: 1–14. | X | |||||

| 33 | 2016 | The Clergy In Khaki (E., Madigan and M., Snape (2013):238). The Juridical Status Of The Chaplains In European Armed Forces. Tăvală, Emanuel. 2016. Jurnalul de Studii Juridice XI, no. 3–4 (2016): 23–41. | X | |||||

| 34 | 2016 | Inter-Religious Relations in the Polish Armed Forces 1918–1939. Rezmer, Waldemar. 2016. Procedia, social and behavioral sciences 236 (December 14, 2016): 374–378. | X | |||||

| 35 | 2016 | Pope Saint John XXIII: Army Medic and Military Hospital Chaplain. Watson, Richard A. 2016. The Linacre quarterly 83, no. 2 (May 2016): 142–143. | X | |||||

| 36 | 2017 | ‘Dextere Sinistram Vertere’: Jesuits as Military Chaplains in the Papal Expeditionary Force to France (1569–70). Civale, Gianclaudio. 2017. Discipline, Moral Reform, and Violence.” Journal of Jesuit Studies 4, no. 4 (August 2017): 559–580. | X | |||||

| 37 | 2017 | A Swiss Protestant Perspective on a Multi-Faith Approach to the Swiss Army Chaplaincy. Inniger, Matthias G, Vorster, Jacobus M, and Evans, Byron. In die skriflig: tydskrif van die Gereformeerde Teologiese Vereniging 51, no. 1 (January 1, 2017): 1–9. | ||||||

| 38 | 2017 | Jesuit Catechisms for Soldiers (Seventeenth-Nineteenth Centuries): Changes and Continuities. Lavenia, Vincenzo. 2017. Journal of Jesuit Studies 4, no. 4 (August 2017): 599–623. | X | |||||

| 39 | 2017 | Italian Jesuits and the Great War: Chaplains and Priest-Soldiers of the Province of Rome. Paiano, Maria. 2017. Journal of Jesuit Studies 4, no. 4 (August 2017): 637–657. | X | |||||

| 40 | 2017 | Flanders and Helmand: Chaplaincy, Faith and Religious Change in the British Army, 1914–2014. Snape, Michael, and Henshaw, Victoria. 2017. Journal of Beliefs & Values: Special Issue in Honour of the Founding Editor of the Journal of Beliefs and Values, Rev’d Dr W. S. Campbell Guest Editors: Editors: Stephen G. Parker, Imran Mogra and Leslie J. Francis 38, no. 2 (May 4, 2017): 199–214. | X | |||||

| 41 | 2017 | For God And/or Emperor: Habsburg Romanian Military Chaplains and Wartime Propaganda in Camps for Returning POWs. Zaharia, Ionela. 2017. European Review of History: Revue européenne d’histoire: Habsburg Home Fronts during the Great War 24, no. 2 (March 4, 2017): 288–304. | X | |||||

| 42 | 2018 | The Russian Army and Navy Ober-Priest G. I. Mansvetov: The Pages Of History of the Army and Navy Clergy (19.09.1827-12.11.1832). Chimarov, Sergey Yuryevich. 2018. Upravlencheskoe konsulʹtirovanie, no. 3 (April 1, 2018): 159–164 | X | |||||

| 43 | 2019 | One to Serve Them All. The Growth of Chaplaincy in Public Institutions in Denmark. Kühle, Lene, and Christensen, Henrik Reintoft. 2019. Social Compass 66, no. 2 (June 2019): 182–197. | X | |||||

| 44 | 2019 | Recommendations to the Military Chaplains of the Border Agency on Raising the Level and Saving the Personal Well-Being of the Staff of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine. Volynets, N. V. 2019. Psychology: theory and practice, no. 1(3) (2019): 32–43. | X |

Appendix B

References

- Bachrach, David. 2003. The Organisation of Military Religion in the Armies of King Edward I of England (1272–1307). Journal of Medieval History 29: 265–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, David. 2011. Military Chaplains and the Religion of War in Ottonian Germany, 919–1024. Religion, State and Society 39: 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Cok, and Hans-Günter Heimbrock. 2007. Researching RE Teachers: RE Teachers as Researchers. Münster: Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Christine R., and Ines-Jacqueline Werker. 2008. Military Chaplaincy in International Operations: A Comparison of Two Different Traditions. Journal of Contemporary Religion 23: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, Doris L. 2001. Totalitarianism: German Military Chaplains in World War II and the Dilemmas of Legitimacy. Church History 70: 232–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besterman-Dahan, Karen, Scott Barnett, Edward Hickling, Christine Elnitsky, Jason Lind, John Skvoretz, and Nicole Antinori. 2012. Bearing the Burden: Deployment Stress among Army National Guard Chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 18: 151–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brante, Thomas. 2010. Professional Fields and Truth Regimes: In Search of Alternative Approaches. Comparative Sociology 9: 843–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Mary. 2014. Confessions of a Prison Chaplain. Winchester: Waterside Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buhai, Sande L. 2012. Profession: A Definition. Fordham Urban Law Journal 40: 241–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cawkill, Paul. 2009. Death in the Armed Forces: Casualty Notification and Bereavement Support in the UK Military. Bereavement Care 28: 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawkill, Paul, and Richard Smith. 2013. Bereavement Support in the UK Armed Forces: The Role of the Army Chaplain. Bereavement Care 32: 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crerar, Duff. 2014. Padres in No Man’s Land: Canadian Chaplains and the Great War, 2nd ed. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, Grace. 2015. The Military Chaplain: A Study in Ambiguity. International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church 15: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler-Dierken, Angelika. 2010. Militärseelsorge Und Friedensethik. Evangelische Theologie 70: 278–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler-Dierken, Angelika. 2011a. Rituale Und Menschenwürde. Jahrbuch Für Recht Und Ethik/Annual Review of Law and Ethics 19: 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Dörfler-Dierken, Angelika. 2011b. The Changing Role of Protestant Military Chaplaincy in Germany: From Raising Military Morale to Praying for Peace 1. Religion, State and Society 39: 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, Lauren N. 2010. Against Bolshevism: Georg Werthmann and the Role of Ideology in the Catholic Military Chaplaincy, 1939–1945. Contemporary European History 19: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelman, Margaret, and Sheldon R. Gelman. 2005. Ethical Considerations in the Changing Environment. Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations 6: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, David. 2014. The Consolation of Soldiers: Religious Life in the Swedish Army during the Great Northern War. Scandinavian Journal of History 39: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkowski, Stacey, and George Wilkes. 2011. Changing Chaplaincy: A Contribution to Debate over the Roles of US and British Military Chaplains in Afghanistan. Religion, State and Society 39: 111–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, Asim. 2015. Muslim Chaplaincy in the UK: The Chaplaincy Approach as a Way to a Modern Imamate. Religion, State & Society 43: 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, James. 2009. The Military Career of Bishop Robert Brindle. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 87: 123–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Kim Philip. 2012. Military Chaplains and Religious Diversity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht, Dieter. 2016. ‘Der König Rief, Und Alle, Alle Kamen’ Jewish Military Chaplains on Duty in the Austro-Hungarian Army during World War I. Jewish Culture and History 17: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbrock, Hans-Günter. 2011. Den Anderen Wahrnehmen—Herausforderungen für Professionelle Praxis in Kirche und Säkularem Gesundheitswesen. Pastoraltheologie 100: 364–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlihan, Patrickj. 2012. Imperial Frameworks of Religion: Catholic Military Chaplains of Germany and Austria-Hungary During the First World War. First World War Studies 3: 165–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howson, Peter. 2007. Deaths among Army Chaplains, 1939–1946. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 85: 162–72. [Google Scholar]

- Howson, Peter. 2011. ‘Command and Control’ in the Royal Army Chaplains’ Department: How Changes in the Method of Selecting the Chaplain General of the British Army Have Altered the Relationship of the Churches and the Army. Religion, State and Society 39: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, James D. 2001. Combat Chaplain: A Thirty-year Vietnam Battle. Denton: University of North Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kariyakarawana, Sunil. 2011. Military Careers and Buddhist Ethics. The International Journal of Leadership in Public Services 7: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Yaacov J. 1994. Chaplain and Counsellor in the Israeli Elementary School: Overlapping or Complementary Roles? Pastoral Care in Education 12: 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, Jessica, Hourani Laurel, Lane Marian E., and Tueller Stephen. 2016. Help-Seeking Behaviors among Active-Duty Military Personnel: Utilization of Chaplains and Other Mental Health Service Providers. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 22: 102–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayrutdinov, Ramil, and Khalim Abdullin. 2015. The Muslim Military Clergy of the Russian Empire at the End of the XVIIIth—Beginning of the XXth Century. Journal of Sustainable Development 8: 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainz, Ulrich. 2015. ‘Newcomer Religions’ As an Organisational Challenge: Recognition of Islam in the Austrian Armed Forces. Religion, State & Society 43: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühle, Lene, and Henrik Reintoft Christensen. 2019. One to Serve Them All. The Growth of Chaplaincy in Public Institutions in Denmark. Social Compass 66: 182–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, Tennant S. 2012. The Chaplain’s Conflict: Good and Evil in a War Hospital, 1943–1945. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2020. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/chaplain (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Michalowski, Ines. 2015. What Is at Stake When Muslims Join the Ranks? An International Comparison of Military Chaplaincy. Religion, State & Society 2015: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nieuwsma, Jason A., George L. Jackson, Mark B. DeKraai, Denise J. Bulling, William C. Cantrell, Jeffrey E. Rhodes, Mark J. Bates, Keith Ethridge, Marian E. Lane, Wendy N. Tenhula, and et al. 2014. Collaborating Across the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense to Integrate Mental Health and Chaplaincy Services. Journal of General Internal Medicine 29: 885–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opata, Josiah N. 2001. Spiritual and Religious Diversity in Prisons: Focusing On How Chaplaincy Assists in Prison Management. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Papkova, Irina. 2011. Russian Orthodox Concordat? Church and State Under Medvedev. Nationalities Papers 39: 667–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Jennifer Shepard. 2017. It’s Kind of a Dichotomy”: Thoughts Related to Calling and Purpose from Pastors Working and Counseling in Urban Resource-Poor Communities. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Patrick. 2005. Beyond Comfort: German and English Military Chaplains and the Memory of the Great War, 1919–1929. Journal of Religious History 29: 258–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, Oliver. 2011. Catholic Chaplains to the British Forces in the First World War. Religion, State and Society 39: 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennick, Joanne Benham. 2011. Canadian Military Chaplains: Bridging the Gap between Alienation and Operational Effectiveness in a Pluralistic and Multicultural Context. Religion, State and Society 39: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Alan C. 2008. Chaplains at War: The Role of Clergymen during World War II. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, Mike. 2012. Defining a Profession: The Role of Knowledge and Expertise. Professions & Professionalism 2: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Christiane. 2017. Editorial. Professions and Professionalism 7: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seddon, Rachel, Edgar Jones, and Neil Greenberg. 2011. The Role of Chaplains in Maintaining the Psychological Health of Military Personnel: An Historical and Contemporary Perspective. Military Medicine 176: 1357–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Settoul, Elyamine. 2015. ‘You’re in the French Army Now!’ Institutionalising Islam in the Republic’s Army. Religion, State & Society 43: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snape, Michael. 2011. Church of England Army Chaplains in the First World War: Goodbye to ‘Goodbye to All That’. The Journal of Ecclesiastical History 62: 318–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeckl, Kristina, and Olivier Roy. 2015. Muslim Soldiers, Muslim Chaplains: The Accommodation of Islam in Western Militaries. Religion, State & Society 43: 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strype, Jon, Helene O. I. Gundhus, Marit Egge, and Atle Ødegård. 2014. Perceptions of Interprofessional Collaboration. Professions & Professionalism 4: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, Richard, and Daniel Susskind. 2015. The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, Christopher. 2014. Hospital Chaplaincy in the Twenty-first Century: The Crisis of Spiritual Care on the NHS, 2nd ed. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Tăvală, Emanuel. 2016. THE CLERGY IN KHAKI (E., Madigan and M., Snape(2013):238). THE JURIDICAL STATUS OF THE CHAPLAINS IN EUROPEAN ARMED FORCES. Jurnalul De Studii Juridice 11. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/32891712/JOURNAL_OF_LEGAL_STUDIES_JURNALUL_DE_STUDII_JURIDICE (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Todd, Andrew. 2009. Reflecting Ethically with British Army Chaplains. The Review of Faith & International Affairs 7: 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas. 1992. The Confederacy’s Fighting Chaplain: Father John B. Bannon. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Volynets, N. 2019. Recommendations to the military chaplains of the border agency on raising the level and saving the personal well-being of the staff of the state border guard service of Ukraine. Psychology: Theory and Practice 1: 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Benjamin, Melissa Bopp, Meghan Baruth, and Jane Peterson. 2016. Health Effects of a Religious Vocation: Perspectives from Christian and Jewish Clergy. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 70: 266–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Derwyn. 2007. Parsons, Priests or Professionals? Transforming the Nineteenth-century Anglican Clergy. Theology 110: 433–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, Israel A. S., Monica Elizabeth Yost, and Michael Markrich. 2006. Combat Chaplain: The Personal Story of the World War II Chaplain of the Japanese American 100th Battalion. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | British Journal of Religious Education 38, Issue 2. (2016). |

| 5 | Zeitschrift für Pädagogik und Theologie 68, Issue 2 (2016). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | (Crerar 2014). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | (Johnson 2001). |

| 10 | (Tucker 1992). |

| 11 | (Opata 2001; Brown 2014). |

| 12 | (Swift 2014). |

| 13 | (Katz 1994). |

| 14 | |

| 15 | (Tăvală 2016). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | (Brante 2010). |

| 21 | (Buhai 2012). |

| 22 | (Saks 2012; Brante 2010). |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | (Schnell 2017). |

| 28 | (Hansen 2012). |

| 29 | (Hansen 2012). |

| 30 | (Hansen 2012). |

| 31 | |

| 32 | |

| 33 | (Hansen 2012). |

| 34 | |

| 35 | (Hafiz 2015). |

| 36 | (Cawkill 2009). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | (Howson 2007). |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | (Hafiz 2015). |

| 43 | |

| 44 | |

| 45 | (Settoul 2015). |

| 46 | |

| 47 | |

| 48 | |

| 49 | (Krainz 2015). |

| 50 | (Papkova 2011). |

| 51 | |

| 52 | |

| 53 | |

| 54 | (Hecht 2016). |

| 55 | (Snape 2011). |

| 56 | |

| 57 | |

| 58 | (Davie 2015). |

| 59 | |

| 60 | (Howson 2007). |

| 61 | (Hagerty 2009). |

| 62 | (Howson 2011). |

| 63 | |

| 64 | (Hafiz 2015). |

| 65 | (Krainz 2015). |

| 66 | (Krainz 2015). |

| 67 | |

| 68 | (Howson 2011). |

| 69 | (Papkova 2011). |

| 70 | |

| 71 | |

| 72 | (Todd 2009). |

| 73 | |

| 74 | (Porter 2005). |

| 75 | (Bergen 2001). |

| 76 | |

| 77 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liuski, T.; Ubani, M. How is Military Chaplaincy in Europe Portrayed in European Scientific Journal Articles between 2000 and 2019? A Multidisciplinary Review. Religions 2020, 11, 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100540

Liuski T, Ubani M. How is Military Chaplaincy in Europe Portrayed in European Scientific Journal Articles between 2000 and 2019? A Multidisciplinary Review. Religions. 2020; 11(10):540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100540

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiuski, Tiia, and Martin Ubani. 2020. "How is Military Chaplaincy in Europe Portrayed in European Scientific Journal Articles between 2000 and 2019? A Multidisciplinary Review" Religions 11, no. 10: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100540

APA StyleLiuski, T., & Ubani, M. (2020). How is Military Chaplaincy in Europe Portrayed in European Scientific Journal Articles between 2000 and 2019? A Multidisciplinary Review. Religions, 11(10), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100540