1. Introduction: Landscape and Public Diplomacy

Roman Catholicism represents a universal Church, but its headquarter, center, and historical identity are European. While its origin lies in the Holy Land between Nazareth, the Sea of Galilee and Jerusalem, Catholicism grew and flourished in Europe, more precisely in Southern, Western, and Central Europe between Rome and Santiago, Avila and Monte Casino, Assisi and Cluny, Paris and Vienna, Canterbury and El Escorial, Cologne and Milan, Pannonhalma and Tours, Paray-le-Monial and Krakow, Mont Saint-Michel and Gargano, Częstochowa and Loretto, Fatima and Lourdes, Armagh and Vilnius, Lwiw and Trieste, Santa Maria di Leuca and Lisbon, to name only a few names of the rich and dense Catholic landscape of Europe.

The global rise of Catholicism that was initiated by the European expansion was mirrored by a simultaneous decline in Europe since the Reformation, sped-up by the French Revolution and the secularization process since the 1960s. While this declining trend was, at various times, interrupted by sudden revivals, Catholic stocks in Europe are currently in a free fall. In the 21st century, the dense Catholic landscape, only sketched above in some historical focal points, is losing more and more its power of attraction and, to many in the young generation, many of these names may not say much anymore.

Since the pontificates of Paul VI and John Paul II, the popes have dedicated much effort to reversing this trend. New evangelization is the term under which the re-construction of Catholicism is sought to be mastered. Paul VI’s

Evangelii nuntiandi (

Paul VI 1975) and John Paul II’s

Ecclesia in Europa (

Paul 2003), in respect to Europe, are the constitutive documents.

The analysis here will not evaluate the results or elaborate options. Within this rich and controversial debate (

Catholic Church 2015), the contribution here specifically concentrates on a comparison between the public strategy of Benedict XVI and Francis from a political science perspective. The focus will be on the travel schedules of these two popes and their political perspectives behind it. The analytical focus is concentrated on a quantitative analysis of the journeys. A brief qualitative look at selected papal texts supports this analysis.

Papal journeys into the more or less Catholic landscapes of Europe and the wider world are the key to understanding the geopolitics of the popes. The argument is that, sufficient to the criteria of parsimony, on that slim data basis of papal travelling a rigorous argument can be made that sheds light onto a complex debate. While both popes focused on Europe, Benedict XVI’s efforts were more concentrated on Europe and what could be called Europe’s Catholic heartlands, while Francis efforts shifted to Asia, and within Europe to the periphery. The difference can be explained by the contrasting idea of a European public open for the project of re-construction: post-traditional European Catholics in the case of Benedict XVI, interreligious migrants in the case of Francis.

However, the popes do not speak to those publics alone. Popes are always heard and watched, at least potentially, by the whole world and the entire Church. The popes mind their words, gestures, and staging in respect to those they address directly and to others they reach indirectly. Popes are able to address national, transnational, regional and local publics, parliaments, assemblies, and associations of any kind and thereby contribute to their specific status towards the addressed counterpart but also to a wider public sphere. Thus, popes speak of inculturation, invite bishops from specific continents for a synod, or take a region, like the Amazonas, to make a very specific, but also very general argument about new evangelization (

Francis 2020). However, they will not explicitly sketch out a geopolitical masterplan or map their cultural heartlands, pivot regions, or strategic targets.

A functional and pragmatic approach to languages is the basic level on which popes structure their geopolitical communication. The focus is on the question who and how many speak what language when and how. While Latin is still the language of the Church, the lingua franca of the Vatican is Italian. Because popes no longer tend to come from Italy alone, they bring their specific language background with them to Rome. More important than this historical or personal impact are the language structures of institutional communication, ranging from the language desks in the Section of General Affairs of the Secretary of States of classical church diplomacy (

Reese 1996) to the language twitter channels of @pontifex of public diplomacy in the digital age (

De Franco 2020;

Löffler 2018). Continents and specific regions, including their diverse cultures, as the basic tenets of geopolitics, structure also papal perspectives, especially when it comes to travelling.

The basic argument, as put forward here, is that travelling is so important for understanding papal geopolitics and their attempts to re-construct a Catholic landscape, because it is a key instrument for the popes to bring public and classical diplomacy together by mobilizing and addressing a specific audience, but effectively also a wider public.

Europe, as it will be shown, is despite a deep transformation, still the top destination of papal travelling. This top rank on the list of Apostolic journeys indicates the importance of Europe for the papacy and the papal attempt to resist the ongoing secularization and pluralization process that might continue to change the already ploughed up European religious landscape. While the pivot Europe is also unchallenged for Pope Francis, the Argentinian pope, the focus within Europe has changed dramatically since the resignation of Benedict XVI. While Benedict XVI concentrated his journeys in Catholic and European heartlands, Francis shifted his focus onto the interreligious periphery of the Balkans and the Caucasus. While Benedict XVI rooted the papal interpretation of the gospel deeply in the cultural soil of Europe, Francis stripped his message from everything that could be understood as cultural baggage that burdens the pilgrims on their ever-closer comradeship on the way to God. It reflects Francis’ point of view on the deep transformation of Europe due to demographic decline and migration. Benedict XVI also understood migration as a sign of the time, but it seemed to be more optimistic about the potential of a Catholic revival in a postsecular European society (

Habermas et al. 2006).

A first section discusses the framework of papal geopolitics of travelling. Drawing on the concept of identity construction through pilgrimages in religious anthropology and nationalism studies (

Anderson 2016;

V. Turner 2006;

V. W. Turner 1995;

Turner and Turner 2011), the mechanism of identity construction through pilgrimage will be explained and applied to the papal approach to the Catholic landscape of Europe. This section explains why travelling is so important and what landscape is at stake in Europe.

A second section analyses the European approach of papal travelling in the two pontificates of Benedict XVI and Francis—until the beginning of the Corona crisis in 2020. Ordered in the chronology of their pontificates, a first step discusses Benedict XVI’s and a second Francis’ European approach. The analysis of the two popes highlights, in both cases, first their common and shifting interest in Europe in the context of their global travelling and then their differences in their mapping of what is important in the European landscape and who are the European publics they are interested in.

2. Geopolitics of Pilgrimage

Modern international papal travelling started with Paul VI’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land during the Second Vatican Council in 1964. The airplane revolutionized since the 1960s papal and political, but also the range of touristic travelling. In respect to the touristic boom of the 19th century by train an eminent church historian stated that “Protestants went on trains to the seaside, Catholics to light a candle in a holy place” (

MacCulloch 2010, p. 820). That statement can be updated for the age of aviation: while politicians went on a plane to shake hands and tourists reached out for far destination seaside resorts, religious leaders and masses constructed via airplane global networks of pilgrimage. Some of these networks, like the one around the Muslim Haj to Mecca, had a huge political impact (

Bianchi 2008). The global communication and transportation nets provide the infrastructure for migration, commerce, and finance, but also for pilgrimages as global phenomena. The outdated story that a secular global network society faces local resistance that is based on religious identities (

Castells 2010) is in need of a considerable correction. Religion fuels globalization as much as trade and finance do. Transnational religious communities use the technical progress in communication and transport to keep in touch with home regions, but also to expand. Pilgrimage can be seen as a key concept for understanding the transformation processes of world society (

Barbato 2013;

Coleman and Eade 2018;

Olsen and Trono 2018;

Ron and Timothy 2019;

Timothy and Olsen 2006).

Within this global trend, the popes understood to link their international travelling and appearance with the mass phenomenon of spiritual tourism and pilgrimage. Like politicians and religious leaders, popes travel to shake hands, negotiate ideas and interests, and deepen diplomatic ties and relations with secular and religious partners. Their rank within the diplomatic balance of power is based on their soft power ability to attract masses in public (

Barbato 2016,

2020b). This kind of internal and external identity formation works as a power mechanism of pilgrimage that will be discussed in this contribution.

Pilgrimage is an important feature of geopolitics, but it is not the only one. Petr Kratochvil and Jana Hovorkova have presented a sophisticated quantitative approach on how to study papal geopolitics through papal speeches. Based on the regular

Urbi et Orbi addresses at Easter Sunday, they focus on the mental map of papal speeches in comparing Benedict XVI with Francis (in the case of Francis until Easter 2015). Africa and the Holy Land are focal points of the mental maps of both popes (

Kratochvíl and Hovorková 2017). However, a look at papal travelling shows a different picture. The Holy Land and its neighborhood are key destinations. However, the Holy Land is only visited once by each pope. Africa, in contrast, ranks low on the travel schedule. Thus, the mental map of

Urbi et Orbi can be read as an attempt to balance and pay tribute to regions which are easier to talk about than to travel to. A qualitative extension of papal speeches revealed that Asia, in particular China, ranks high on Benedict XVI’s agenda (

Dubois 2007;

Friedrichs 2020). This, again, cannot be detected by the focus on quantitative analysis of addresses or journeys. The focus of pilgrimage does not deliver the whole picture, but it brings an important part of it to the fore. To understand the geopolitics of papal travelling in Europe, at least a brief look on the historical Catholic landscape of Europe, but also on Europe as part of the global papal picture of world and Church, is necessary to structure the analysis of the papal journeys with geographical categories and frame the design of the research agenda. Together with the conceptualization of the power mechanism of pilgrimage, the overview of the European landscape provides the theoretical and historical background for the analysis of papal travelling in the cases of Benedict XVI and Francis in Europe.

2.1. The Power Mechanism of Pilgrimage

The power of the pope, as an institutional religious and political actor, rests on the ability to combine societal and political forces in order to promote his ideas and interests. Arnold Wolfer’s classical approach of milieu and possession goals (

Wolfers 1965, pp. 67–80) have been applied (

Ryall 1998;

Troy 2018) in order to conceptualize papal ideas and interests within a foreign policy discourse. Wolfers defined “milieu goals” as aims focused on the “shape of the environment in which the nation operates” (

Wolfers 1965, pp. 73–74) and Joseph Nye understood a persuasive kind of power that he termed “soft power” as particularly suitable to achieve milieu goals (

Nye 2004, pp. 16–17). Nye himself (

Nye 2004, pp. 9, 94) and others (

Byrnes 2017;

Crespo and Gregory 2020;

Sommeregger 2011;

Troy 2010) understood the moral authority of the popes also as soft power. Nye is not shy to underpin that also soft power actors’ prestige can gain if they are able to display hard power, too (

Nye 2004, p. 26).

Population is a key factor, even in neorealists approaches of hard power, as it constitutes a latent power (

Mearsheimer 2014, pp. 55–67). The pope has with 1.3 billion Catholics a large latent power. These are the famous legions of the pope Churchill was aware of when Stalin mocked about the pope. Churchill’s remark that these legions are not always visible on parade is certainly true. However, sometimes they become visible on parade when papal pilgrims come to Rome to see the pope or the pope travels in order to show himself to the people. Papal pilgrimage is an exercise in soft power, but it is backed by the latent hard power of supportive masses (

Barbato 2016).

Such an understanding is based on Benedict Anderson’s argument concerning the impact of identity formation through pilgrimage, which he develops for his interest in nationalism (

Anderson 2016, p. 114). Any kind of external power display has to be based on an internal and integrative soft power that constitutes as common identity. Based on the insights of the anthropological studies of Victor Turner on pilgrimage (

V. Turner 2006;

V. W. Turner 1995;

Turner and Turner 2011), Anderson understands pilgrimage as an experience that creates communities. When people from distant communities, different tongues and heterogeneous backgrounds meet at a shrine with people they can hardly talk to, the common experience of the religious ritual constitutes the new community: “The Berber encountering the Malay before the Kaaba must, as it were, ask himself: ‘Why is this man doing what I am doing, uttering the same words that I am uttering, even though we cannot talk to one another’ There is only one answer, once one has learnt it: ‘Because we … are Muslims’” (

Anderson 2016, p. 54). The papal pilgrims make this experience of community every time they watch and hear the pope—most of the international pilgrims do not understand his Italian words—at St. Peter’s Square. The World Youth Days or other Catholic rallies, like Eucharistic Congresses, and World Family Meetings where the travelling popes can encounter masses in varying places world-wide have a similar function. Of particular interest for papal visits are shrines that have as such an appeal for pilgrims. Marian shrines, like Guadalupe, Lourdes, or Fatima, are of particular value for the popes. If pilgrims attend the papal traveler in their home country, they might get a translation of his word and meet no other nationals than their fellow citizens, but they experience a belonging beyond, sometimes in contrast to their nation and their secular or non-Catholic environment.

These interpersonal experiences also have a public and a political dimension. Anderson stresses also the aspect of statecraft which emerges from these personal encounters, experiences and imaginations: “It is not simply that in the minds of Christians, Muslims or Hindus the cities of Rome, Mecca, or Benares were the centres of sacred geographies, but that their centrality was experienced and ‘realized’ (in the stagecraft sense) by the constant flow of pilgrims moving towards them from remote and otherwise unrelated localities. Indeed, in some sense, the outer limits of the old religious communities of the imagination were determined by which pilgrimages people made” (

Anderson 2016, p. 56). This power of pilgrimages to shape geopolitical realities is at the heart of the geopolitical agenda of papal travelling.

Anderson is also instructive to understand how the mass movements of pilgrimage can be used for soft power achievements of an elite, in the case here the popes and his clergy. Anderson highlights the fact that the pilgrim community is not a spontaneous crowd, but that it is held together and supported in their experiences and imaginations by a deliberate elite: “There was, to be sure, always a double aspect to the choreography of the great religious pilgrimage: a vast horde of illiterate vernacular-speakers provided the dense, physical reality of the ceremonial passage; while a small segment of literate bilingual adepts drawn from each vernacular community performed the unifying rites, interpreting to their respective following the meaning of their collective motion” (

Anderson 2016, p. 54). There is no need to reduce this mechanism to an illiterate mass; it works equally with well-educated modern men and women. The only religious community that established a hierarchical structured elite that spans the globe and brings it back to one center is the Catholic Church and the papacy. No other religious community has a hierarchical elite that can act in this way like the Catholic clergy can.

Based on a working internal power mechanism of pilgrimage, the popes are able to reinforce the Catholic identity and the loyalty to pope, Church, and faith of those who attend their public appearances. In addition, a powerful display of internal soft power can also constitute an external soft power appeal to bystanders. A latent power became visible, as papal pilgrims are not just Catholic numbers in statistics, but mobilized forces in support of the pope and of the Catholic cause. One of the most powerful effects happened during the first visit of John Paul II in Poland when the people realized that Catholicism, and not communism, was the strongest social bond of their nation (

Bösch 2020).

The Polish experience was an extraordinary case but the interplay of soft and hard power during state visits is an important general feature of the travelling pope. While always having to maintain the delicate balance between his religious and his political role, the pope can try to achieve his goals either by deepening diplomatic ties with the government of the country he is visiting or, particularly in cases when a government is not happy to host the pope, by addressing the society. In most cases, the pope will not choose between one of the extremes but combine classical diplomacy and public diplomacy. In any case, the support of the mobilized masses during the visit and the general support of the papal claim as a public and diplomatic actor help to reinforce Catholic identity in the specifically addressed public. It can also have an effect on a wider friendly or hostile public and is so able to project internal and external soft power. Often, popes do not aim at a monolithically Catholic public and their Catholic identity construction. A papal strategy of travelling addresses a pluralist and interfaith public, in which the popes try to achieve a powerful middle ground for Catholicism and encourage the Catholic flock not to rally only around the flag but to engage in an encounter with a wider public as the popes do themselves. Thus, the geopolitics of travelling popes aims not necessarily on a re-conquest of Catholic soil, but has a flexible and broader agenda of Catholic milieu goals.

2.2. Geopolitics of Catholic Europe

Papal geopolitics have a strong and deep historical dimension in Europe, in a global as well as in a European perspective. The Roman popes are heirs of the Apostle Peter, but also of the Roman Empire. For both reasons, papal power has a Mediterranean center, based in Rome, and looking toward Jerusalem. While the moral authority of the popes is no longer invested to call for crusades to liberate the Holy Land, as the Medieval papacy did (

Hall 1997), the Middle East is still of high importance for the papal traveler (

Barbato 2020c,

2020d). As an expansive power, the missionary papacy participated in the European expansion, colonialism, and imperialism. It took the papacy until Benedict’s XV hallmark document

Maximum illud in 1919 (

Benedict XV 1919) to liberate the Catholic mission from the imperialist dominance of the European states. This had a major impact and allowed for the survival and flourishing of the Catholic Church and the global outreach of the papacy during and after the decolonization process in the Global South. The Catholic Church has become a genuinely universal Church that is shifting its population center steadily southwards. However, the center is still in Rome, on the Italian peninsula, on the European shelf of the Mediterranean Sea. The global perspective of the papacy is established and it is most likely to move the future geopolitical outlook of the papacy even further towards a pluralist view of the world—Pope Francis likes to talk about the world as a polyhedron in contrast to a sphere focused on a center (

Francis 2013, para. 236). However, the Vatican residence at the Tomb of the Apostle Peter will also continue to have an impact on the papal point of world view, but, in particular, on the importance the popes ascribe to Europe, with a Mediterranean bias towards the Middle East. Hence, embedded in a global perspective, Europe ranks high on the mental map of the papacy, not only as a historical remnant or memory, but as a current and future reality of a geopolitical concern. However, the shadows of the past continue to structure the Catholic landscape of Europe.

Historically, the Roman papacy is the heir of West Rome. It was, at the latest, the East-West Schism of 1054 that reduced the papacy to a West European power that only has weak influence on the Christian culture of Eastern Europe, eastwards to a line from Vilnius to Lwiw, and South East Europe or the Balkans, south eastwards to a line from Zagreb to Cluj. In these regions, Catholics constitute a tiny minority, despite the Venetian or Austrian dominance during some periods in history. Catholicism plays almost no role in the Caucasus. The papal way to the North was supported by Hiberno-Scottish and later Anglo-Saxon mission and by the Frankish alliance with the pope. The Anglican split from the pope and the Reformation pushed Roman Catholicism out of Northern Europe. While the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution meant a further blow to Catholic Europe, which destroyed through the impact on Italian nationalism even the Papal States and lead to the fierce persecution of Catholics during the Spanish Civil War, the papal impact was less affected. The local and national structure of episcopal or monastical power came down with the ancient regime while the popes had the ability to mobilize masses and hold and gain ground in the power vacuum left by revolutionary turmoil. These historical backgrounds still structure the realities of the papal map and its itineraries in Europe (

Brown 2013;

Carroll and Carroll 2013;

Greengrass 2015).

Towards the East, South East, but also the North, an interreligious and ecumenical encounter is key. While the North is dominated by the Reformation, in the East the counterpart is Orthodox Christianity. In the Balkans and in the Caucasus, the landscape is diverse and includes Islam as a dominant factor that links this geopolitical area, including Turkey, to the Middle East, and its important historical landscape for Catholicism. The old Catholic strongholds in the South and in the center of Europe are secularized or secularizing areas, even in the outposts Ireland and Poland, which constructed their national identities also as Catholic due to their non-Catholic, but imperialist and expansionist neighbors. However, a pope hoping for the new evangelization of the old Catholic nations will focus his journeys on the old centers and nations with a Catholic past from Spain to France and the heirs of the Roman Empire, Germany, particularly the South and the West, and Austria and the former parts of the Habsburgs Empire. Popes who do not believe in a recovery of the old Christendom that is based on the Catholic culture of Europe might be more interested in encountering the peripheral, pluralist, and interreligious areas. As we will see, Benedict XVI’s journeys stand for the first, Francis’ for the second geopolitical approach to Europe’s Catholic landscape.

3. Papal Travelling

When the Papal States finally collapsed under the onslaught of the emerging Italian nation state and Rome fell in 1870, touristic travelling to Italy was about to boom as a mass phenomenon. In the decades to come, the traditional Grand Tour transformed and increased into a leisure activity that manifested itself in the Grand Hotels of the Belle Epoque. Within these developments, the pilgrimage in support of the self-declared papal “prisoner in the Vatican” also boomed. During the pontificate of Pius IX and Leo XIII, the modern mass pilgrimage to Rome was established.

Again, within a transition of global tourism, the popes became themselves pilgrims. John XXIII made the first papal pilgrimage after the end of the Papal States in 1870 within Italian territory to Assisi and Loretto in 1962 at the occasion of the opening of the Second Vatican Council. Paul VI made the first international pilgrimage to the Holy Land at the occasion of the continuation of the Second Vatican Council in 1964. At home in Rome, he was also the pope who turned the papal audiences in a general mass event. The audience hall next to St. Peter, which he built to continue the ritual also during winter time and under poor weather conditions, now bears his name. He has to be credited as the master mind who modernized the papal scheme of mass mobilization that had been invented by Pio IX and Leo XIII.

In the same year of his initial pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1964, Paul VI made an Apostolic journey to the Eucharistic World Congress in India. Attending a mass event allowed the popes to also expect in countries with Catholic minorities a mutual boosting effect of mobilization. Also based on the success of mass mobilization beyond Catholic majority countries, Paul VI was able to speak to the U.N. General Assembly in New York in 1965. In 1967, he made a pilgrimage to Fatima in Portugal. Marian shrines became a key destination for travelling popes. In the same year he went to Turkey in particular for an ecumenical meeting with the Orthodox patriarch, whom he had met already in Jerusalem, and other interreligious encounters, but also for a pilgrimage to a historical landscape of Catholic tradition in Ephesus and Smyrna. In 1968, he came to Bogota in Colombia to visit the dominantly Catholic Latin America but also to underpin his encyclical letter Populorum Progressio, which addressed the post-colonial world of developing countries and offered the answer of Catholic social doctrine to the modernization schemes of the era. His journey to Geneva in the same year was a diplomatic visit to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the International Labour Organization, which had its headquarter there. It became also an ecumenical encounter with the Ecumenical Council of Churches, which is now the World Council of Churches. In 1969, the pope made a journey to Africa and visited Uganda. At his final trip, he reached East Asia, Oceania, and Australia, with stop-overs in Iran (then still ruled by the Sha) and Pakistan. The most important destination was Manila, Philippines, the most Catholic country in Asia, but the pope could also make the point that he toured the world. Paul VI has been dubbed the first modern pope, which underestimates the performance of his predecessors. But it is certainly appropriate to name him the first global pope as he visited all continents.

Paul VI was a less frequent traveler in Italy where he visited only the National Eucharistic Congress in Pisa in 1965 and the Marian shrine of Bonaria in Sardinia in 1970. Until his death in 1975, he made no more journeys. This was not an option for Benedict XVI. When he felt unease to make a transatlantic flight to the World Youth Day scheduled for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 2013, he resigned. Of course, the papal resignation is a complex issue and a combination of different reasons may have played a role. However, Benedict XVI himself answered in the long interview with Peter Seewald that he made the decision in the context of the papal travelling schedule and in the perspective of World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro after his doctor told him that he should not cross the Atlantic again (

Benedict XVI 2016, p. 40). Papal travelling had turned from a papal option into a papal necessity. The pontificate of John Paul II made the difference as he turned papal travelling into a papal duty. In 104 journeys he visited 127 countries. Thus, it can be said that while Paul VI was the inventor of papal travelling, John Paul II brought papal travelling to perfection. He also frequently toured Italy. The frequency of papal travelling also rose remarkably. The itinerary of Paul VI outlined already a global strategy for papal travelling. The seminal figure of John Paul II and his impact on papal travelling cannot be overestimated (

Zajączkowski 2020). Here, within the context of Benedict XVI’s and Francis’ travelling, only a very limited look is possible. The overall strategy of John Paul II kept the universal perspective of Paul VI. However, there was also a specific focus that can be detected by looking at the countries that have been visited most. The Cold War and the support for the Solidarity movement in his home country Poland ranked high. The Cold War objective brought him also to Latin America in order to reject the Marxist interpretation of the liberation theology and to the United States. Western Europe was also significant in preventing the liberal version of secularization. Looking back, particularly with regard to the visit in the Netherlands, this objective was not met.

Benedict XVI’s heartland strategy can be understood as an attempt to focus on the declining Catholic landscape in Europe. Francis dramatically altered the approach with his focus on the periphery. The in-depth analysis of the journeys of Benedict XVI and Francis (until the corona crisis in 2020) shows the details of the continuities but also a sea change adaptation.

Like their predecessor, Benedict XVI and Francis also frequently toured Italy. In order to avoid an imbalance, only international travelling beyond Italy is included in the analysis of both pontificates. All of the dates concerning papal pilgrimage here and in the following analysis are taken from the homepage of the Holy See:

www.vatican.va. A quantitative analysis of the visits visualized with

Voyant tools shows in a first step the still dominant, but shrinking, European focus within the global papal travelling. In a second step, it can also show the shifts within Europe from the heartland to the periphery. A third qualitative step hints at one possible explanation: While Benedict XVI believed in a possible return of former Catholics and engaged himself in the intellectual debates with secular agnostics about a postsecular society, Francis’s analysis is based on the demographic decline of the population in the center and trusts in the masses of migrants from the periphery and an emerging interreligious landscape of Europe.

3.1. Pope Benedict XVI: Catholic Heartlands

Benedict XVI continued John Paul II’s global tour as a papal pilgrim and resigned when he was no longer able to do so (

Benedict XVI 2016, p. 40). Thus, travelling was, without doubt, a key instrument of his pontificate. From a geopolitical perspective of his travelling, a specific focus can be detected. Europe and the Middle East constituted the epicenter of Benedict XVI’s travel schedule. It stands for the traditional heartland of Catholicism. A closer look also shows a very specific pattern within these regions:

Biblical Levant and its neighborhood and Western, Southern, and Central Europe, Orient, and Occident were the key destinations of Benedict XVI’s pontificate. The Biblical Levante comprises the Holy Land (Israel, Palestine, Jordan) and Lebanon. Its relevant neighborhood constitutes the bridge to Europe, the Aegean Sea including Malta, or the way St. Paul took to bring the Gospel to Europe. Western and Southern Europe consists in the papal travel schedule of the Iberian Peninsula and the major powers UK and France. Central Europe is Germany, including his own home region Bavaria, and countries that belonged to the old Habsburg Empire, including Poland, more precisely Silesia, the home of John Paul II, the Czech Republic, Austria, and Croatia.

Based on a quantitative analysis of the global travel list of his pontificate, it can be shown that Europe stands in the center of the pontificate of Benedict XVI. The Holy Land and Middle East have a particular place in the papal geography. For that reason, the Middle East is not split up into Africa and Asia but integrated as a region of its own. The first quantitative analysis counts each country and continent or region for each visit. One visit that included two countries and one continent or region scores one for the continent or region and one for each country. Within this logic, Australia has to be counted twice and appears, hence, larger in the graphic than on the travel schedule.

The

Voyant tools allow for a visual overview of the result. The higher the score per country, continent, and region, the large appears the name of the country, continent, and region in the Figure.

Figure 1 shows a clear result. Europe appears in the largest letters. The Middle East is also of high importance. Germany and Spain are particular intensively visited countries.

Benedict XVI visited 24 countries. Sixteen countries, two-thirds of the total schedule, were in Europe or the Middle East. 11 countries, almost half of the total schedule, were European. Before we concentrate on Europe, a brief sketch on the global context seems to be in order to understand the relevance of Europe in the global papal perspective of geopolitics.

The ecumenical dialogue with the Orthodoxy and the interreligious dialogue with Judaism and Islam stood in the center of the journey to the Orient. The contested Regensburg Lecture during his visit in Bavaria, which challenged not only the domination of Islam in the Orient, but also the hegemony of secular enlightenment in the Occident, could be seen as the most programmatic address he gave during his travels. Despite the criticism and riots due to a critical quote concerning the contribution of the Prophet, his following journey to Turkey was a success. Success or failure are defined here and throughout the analysis only in respect to short-term reactions of media, masses, and crucial representatives of elites. During his last journey, which brought him to Lebanon in order to present the post-synodal exhortation Medio in Oriente, he praised the Arab Spring and pled strongly for an interreligious community in the Middle East. Benedict XVI became the first pope who visited the Dome of Rock in Jerusalem. A particularly important task for a pope, especially a pope from Germany, was the dialogue with Judaism. Auschwitz and Yad Vashem were the two critical moments of his journeys in this respect.

America ranked second after the Middle East. America could be understood as a kind of extension of the European heartland of Catholicism. Benedict XVI celebrated his 81st birthday the day he was welcomed by President George W. Bush at the White House. During that journey, he also addressed the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York. Benedict XVI visited Brazil at the occasion of the VI CELAM assembly at Aparecida. At the major South American Marian shrine, he defended the Christian mission during the colonial era. He made also a visit to Cuba and Mexico, but left out Mexico City, and the Virgen de Guadelupe, a major hub for John Paul II’s travel diplomacy.

Benedict XVI visited three African countries on two journeys: Cameroon, Angola, and Benin. The African journeys were focused on synods of bishops and also included mass gathering at Marian Shrines.

One of three World Youth days during his pontificate took place in Sydney, Australia. Despite the long journey, Benedict XVI did not take the opportunity for a stop-over in an East or South Asian Country. Diplomatically, East Asia ranked high due to his efforts to come to terms with China and Vietnam. They were successful in the case of Vietnam, but Benedict XVI seemed to have refused to accept the deal the then undersecretary Parolin negotiated with Beijing, arguably the starting point for the secret agreement Parolin made with Beijing during Francis pontificate (

Friedrichs 2020).

This remark on the Asian policy of Benedict XVI shows that the geopolitical map of papal travelling does not show the whole story of a political pontificate. However, the papal travel schedule highlights that Benedict XVI was determined to present a focused, coherent, and ambitious program to the declining heartland of Catholic identity under threat by political Islam in the Orient and by liberal secularism in the Occident. A closer look on the European visits shows this objective.

In the second quantitative analysis, the names of the European countries are counted as before, while the names of continent are replaced by regional terms: Central, South, West appear, North, and East not. Again, the results, as visualized by

Voyant tools in

Figure 2, are clear. The two most visited countries Spain and Germany support the importance of South and Central Europe. The other visited countries support this trend. North and East are missing completely. The West appears in rather small letters.

The pope, who choose the name of Benedict of Nursia, Paul VI’s Patron Saint of Europe, visited 11 European countries. Almost half of the 24 countries that were visited by the pope were European. Spain and Germany were visited three times, including two World Youth Days, and one World Family Meeting. Thus, it is safe to say that, quantitatively, the Occident is for Benedict XVI the major part of the Heartland. The picture could be changed a little bit if Cyprus and Malta were not counted as South, but as part of a further category towards the South East and the Middle East. This already anticipates the sea-changing development of the pontificate of his successor.

The choice of locating two (out of three in his pontificate) World Youth Days (Cologne was already planned by John Paul II, but Madrid was Benedict XVI’s decision, and one World Family Meeting in Europe (again in Spain, in Valencia) indicates additionally that the declining Christian Occident was the major concern of Benedict XVI’s pontificate. He managed to give three major addresses to the public and political elites of the Western powers: Bundestag (Berlin), Westminster Hall (London), and Collège des Bernardins (Paris). The public and political culture being informed by the Christian heritage, bringing faith and reason together in the public sphere of arguing, was the common theme of these speeches. Despite ongoing trends of secularization and differentiation in those countries, his capacity as a public intellectual enabled that—in Berlin and the Bundestag contested—success of envisaging a postsecular society. Refusing to address the European Parliament in 2008, during President Pöttering’s—a German Catholic Christian Democrat—Intercultural Year, underlined his agenda of containing secularism: For instance, the members of the European Parliament had, at the beginning of that election period, rejected the Catholic Rocco Buttiglione as commissioner because of his Catholic stance on homosexuality. The Catholic identity was supported by diverse Marian pilgrimages, including two anniversaries (850 years Mariazell, 150 years Lourdes), but also the major sites of Fatima, Czestochowa, Altötting, and regional sites, like Etzelsbach in Eichsfeld. Of importance for the Catholic European identity was also the visit to Santiago de Compostela.

While interreligious dialogue was an aspect, ecumenical encounters with Churches of the Reformation ranked high during his visits in the United Kingdom and Germany. While Benedict XVI was determined to make strong gestures, he was not willing to compromise essentials. The Queen had to see him in Edinburgh, where she is not Head of the Church, but only Head of the State. However, the journey to England, including the beatification of John Henry Newman as a bridge to Anglican Catholicism, was a success. German Lutherans were not completely satisfied after their meeting with the pope in Erfurt.

In sum, Benedict’s journey reflected his overall approach that he already pursued during his term as the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and in numerous encounters and publications. He was determined to explain that faith and reason can come together and that the European Christian heritage is worth to be maintained and cultivated. His audience was the post-Christian and post-secular public of Enlightened Europe, in mass gatherings, and in Parliaments. The lost heartlands in South, Central, and Western Europe and its previously Catholic population were the main audience for his attempt to the new evangelization of Europe. For the time being, the effort was in vain, if a re-conversion to Catholicism was the motivation.

3.2. Pope Francis: Interreligious Periphery

Evaluating Benedict XVI’s approach from the perspective of his successor’s travel program indicates that the Orient responded more positively than the Occident to the papal initiatives. Francis successfully continued to concentrate his efforts on the Muslim world of the Middle East. He appears to have almost given up South, Central, and Western Europe. As a summary, one could state: when the center collapses, the periphery becomes central. Or as Francis put it himself in an interview with La Cárcova News, quoted here in an English translation:

“Normally we move in areas that we control to some extent; this is the center. But as we go away from the center, we discover new things. And when we look at the center from these new things we discover, from our new viewpoint, from this “periphery”, we see that reality is very different. It is one thing to see reality from the center, and another thing entirely to see it from the last place you arrive at. For example, Europe, seen from the perspective of Madrid in the 16th century was one thing, but when Magellan arrived in South America and looked at Europe, from there he understood something completely different.” (

Plowden 2015).

A first analysis of the global travel data demonstrates that Europe is still a priority, however it is fading away. The Middle East is stable. America is on the rise, and Africa is stable in absolute numbers, but in relative decline. Asia now significantly appears in the data. No country has been visited twice, except Cuba. Again, the

Voyant tools allow for a visualization of the overview in

Figure 3:

The global travel data show for Europe and the Middle East twenty-two countries. Thus, the heartland is still in focus. However, Francis visited 45 countries all together. The heartland of Europe and the Middle East attracted now less than a half of the country visits. During the previous pontificate, we had seen a share of almost a half of Europe alone and two-thirds for the heartlands together. America caught up and has now ten visited countries. East and South East Asia has now seven visited countries, while Benedict XVI had not toured the region at all. Francis visited six Sub-Saharan African countries.

In sum, Europe lost significantly. Only if America is added, the previous two-thirds threshold of the heartlands of the Middle East and Europe is reached. Asia overtook Africa, which is, together with Europe, the loser on the travel scheme. Francis periphery strategy is strong on Asia, but it clearly lacks an African interest or focus. Given the rise of the Catholic flock, the poverty, the conflicts, including the clashes with the competing Islam, the ecological situation, and the image of the most backward and lost continent of the Global South, this lack of interest is astonishing.

A closer look at the global data reveals insights that are also relevant for the European analysis: The importance of the Middle East was not abandoned but adjusted from a focus on a critical public discourse of dialogue to a more diplomatic elite-focused strategy. Francis visited the Holy Land early-on. However, the main focus was an agreement with the Muslim world. He managed to reestablish the dialogue with the Al-Azhar University in Cairo and Grand Imam al-Tayyeb and visited first Egypt before he went to Abu Dhabi in order to sign together with the Grand Iman the Document on Human Fraternity but also to celebrate the first papal mass of the Arab Peninsula mainly with the Christian migrant workers. Migrant workers constitute the majority of the population at the Gulf. He visited also Morocco where he signed a Declaration on Jerusalem as a place for all religions. Here, Francis successfully adapted the strategy of his two predecessors, but no major shift occurred (

Barbato 2020a,

2020c,

2020d). However, migration ranked now very high as an issue.

The Argentinian pope has not been to Argentina so far. Latin America became more important but not the dominant destination. He visited 10 Latin American countries and the USA. The periphery strategy is here particularly dominant with the Amazonas metaphor for the periphery that becomes a new heartland or, better, the lung of the world. However, it is not only an issue of ecology, but also one of encounter with indigenous and marginalized people. Two out of three World Youth Days were in South America while only one was in Europe. The next one is scheduled for Lisbon, which has to be seen as a bridge to Latin America, postponed to 2023. Cuba was so far the only country that has been visited twice, both times as an important diplomatic stop-over, making the point that the Holy See helped to reestablish diplomatic relations between the USA and Cuba and in order to meet the Russian Patriarch Kirill, who was not willing to invite the pope to Russia. Cuba became a papal hub to make world politics. The address to the Joint Session of Congress in Washington was a major event. The issue of migration was not only in Europe, but also in America prominent, particularly during the visit in Mexico and the United States. Marian Shrines continued to be part of the identity construction. A new symbolic gesture in this respect is the regular visit in Santa Maria Maggiore, the major Marian sanctuary in Rome, before every departure and after arrival.

South East and East Asia appeared with seven countries prominently on Francis’ schedule. The pope was in South Korea, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Japan. Only in Philippines were huge Catholic masses part of the picture. There, however, on the most massive scale: 6–7 million people attended the largest papal service so far in Manila. In the other countries, Catholics are a small minority. Interfaith and peace were the most prominent issues. South Korea and Sri Lanka were important destinations to stress the papal engagement for peace, Hiroshima and Nagasaki produced the most powerful pictures. The Rohingya issue in Myanmar was the most difficult problem to handle diplomatically.

Africa was the last, and if only, Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding Egypt and Morocco as part of the Greater Middle East) is counted, least visited continent, with only six countries. The first three countries were Kenya, Uganda, and Central African Republic in November 2015, more than two years after the beginning of his pontificate. In the Central African Republic, Francis was able to have a positive impact on the Muslim–Christian tensions and made the powerful periphery gesture to open the Holy Door of the Cathedral of Brazzaville to mark the beginning of the Extraordinary Holy Year of Mercy. In 2019, he made a second trip to Madagascar, Mauritius, and Mozambique. While the first trip can be seen as a visit to the heart of Africa, the second clearly touched the periphery. Surprisingly, Australia and Oceania have not been reached so far.

The corona crisis interrupted the papal travel program. No international trips are announced for 2020 and, most likely, 2021 might also be a year without international travelling, as the Italian newspaper

La Repubblica speculated (

Rodari 2020). The lack of travelling will, if the thesis of public power through pilgrimage put forward here is correct, significantly reduce the impact of the pontificate on public and politics.

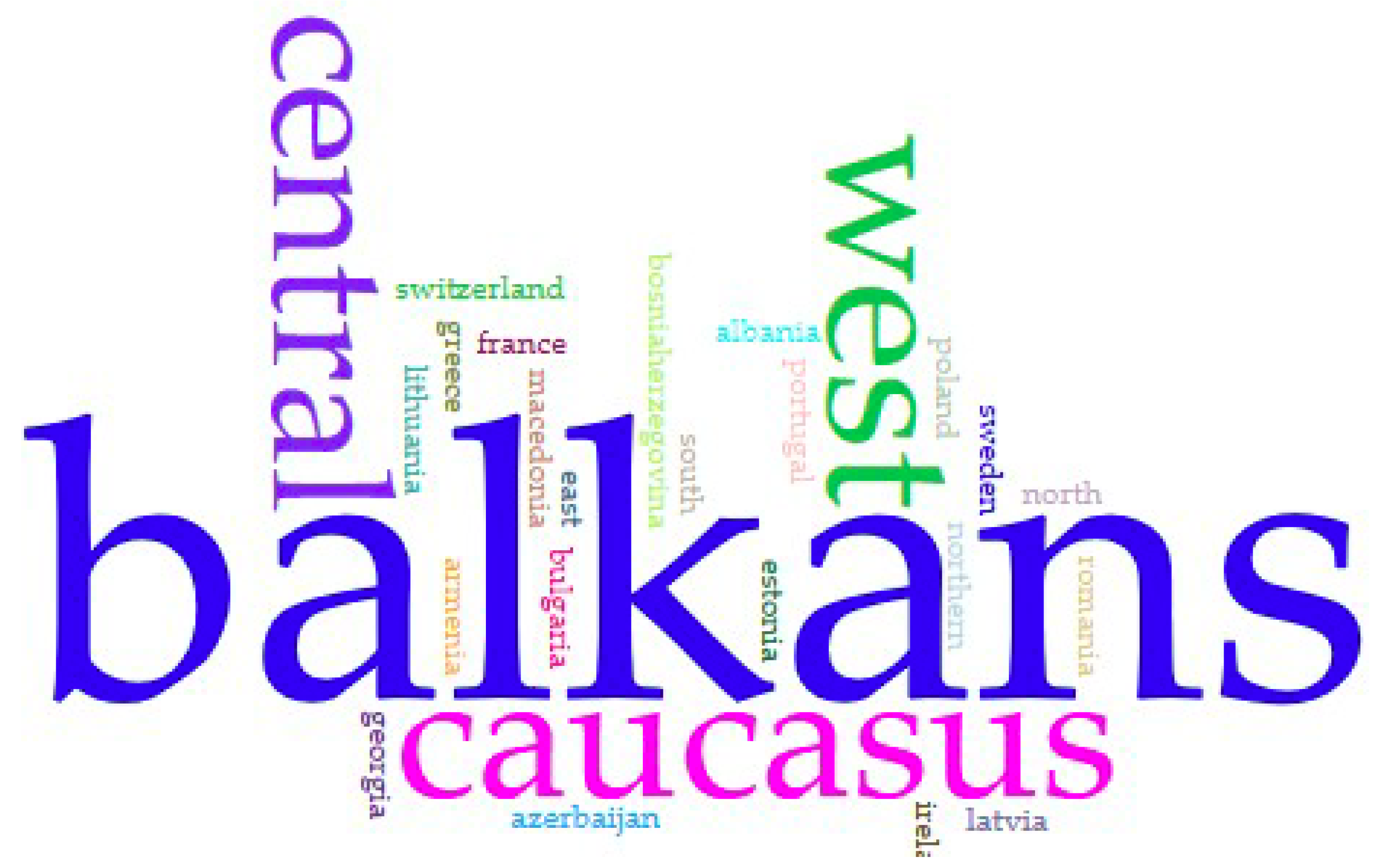

Again, a second analysis focusses on the European travel data alone. A closer look at Europe shows the sea-change of the geopolitical focus of the two pontificates.

Voyant tools make the results visible in

Figure 4. No country is visited twice. All European regions appear. However, new regions had to be included to highlight the shift of interest. These new regional categories in the periphery rank high. The periphery of the Balkans and the Caucasus became dominant. The South is as visible as the North and the East; each region was visited once. The Central and the West are still important, but replaced or matched by the Balkans and the Caucasus as the most important regions.

In contrast to Benedict XVI, Francis addressed the European Parliament, accepted the Aachener Karlspreis, and received the Head of States of the European Union at the occasion of the 60 years celebration of the Treaty of Rome. However, he did not use the opportunity of his visit to Strasburg for a pastoral journey to France. He avoided visits to Germany, UK, and Spain completely. He was in Poland for the World Youth Day in Krakow during the Extraordinary Year of Mercy and, thus, paid tribute to the legacy of John Paul II. He visited also Czestochowa and Auschwitz but did not tour Poland. The other European trips show all of the alternative strategy of going to the periphery.

His first European journey as pope brought Francis to Albania, the second to the Parliamentary center of Strasbourg. The engagement of the center from the perspective of the periphery could have not been better scheduled. In the following journeys, he touched the Western shore of Europe in Portugal (100th anniversary of Fatima and canonization of Jacinta and Francisco Marto) and Ireland (World Family Meeting and the Marian Shrine of Knock). While both countries Ireland and Portugal were geographically on the periphery, both were heartlands of the Catholic faith. This can also be said about Lithuania, which he visited as part of the Baltic journey. However, the trip to Estonia and Latvia was rather a journey to post-Christian countries with a Protestant heritage. The ecumenical encounter was the purpose of the journeys to Lund (Sweden), where the pope visited the Lutheran World Federation at the occasion of the jubilee of the Reformation, and to Geneva (Switzerland), where he visited the World Council of Churches. The most important cluster of the European periphery strategy was applied in the Balkans. In addition to Albania, Francis visited Bosnia-Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Romania. Interfaith encounters and peace were the messages of these trips.

A similar point was made with the Caucasian journeys, first to Armenia, where he spoke about the Genocide, then to Georgia and Azerbaijan. In all of these countries, Catholics are a small, most often a tiny, minority. The encounter with Orthodox churches and Muslim communities stood at the center. The Balkans and the Caucasus cluster already marked a bridge to the Middle East and the encounter with Islam.

A very important journey was made to Lesbos, where the ecumenical encounter with the Orthodox Church of Greece was focused on orthopraxy: caring for the migrants. Lesbos became a papal destination, like the first papal trip to the Italian island Lampedusa, in order to underline the papal approach to welcoming the stranger and the migrant.

The geopolitical space of papal journeys has a clear message: Francis conceptualized Europe not as the Occident in contrast to the Orient but as an open space which can and should be reconstructed from the periphery. Given the secularizing decline of the old Christendom, one can conclude that Benedict XVI’s heartland strategy is seen as a last call in vain for a Christian Europe. Instead, a pluralist and interreligious Europe based on interfaith encounters is envisaged. The major powers of Europe are not seen as powerful enough to rely on them as close or key partners. This mirrors not only the decline of European Christendom, but also the decline of Europe as a political power.

Of particular importance is the focus on migration. The papal audience is no longer primarily the post-Christian European population that Benedict addressed in order to remember them on their Christian heritage. It is a migrant population that starts at the periphery but reaches out for the old heartland. Francis is very outspoken regarding the demographic decline in Europe. The intertwined factor of demographic decline and secularization (

Norris and Inglehart 2011) threatens the existence of the Catholicism in Europe. To remedy this problem, Francis believes more in the option to concentrate new evangelization attempts on the masses of migrants than on the intellectual public discourse of his predecessor. From that perspective, it becomes obvious why he is travelling to peripheric regions and why he is not interested to pay much tribute to the cultural heritage of Europe. If the culture is under pressure and a deep transformation of the population is anticipated, siding with the culture might be a less successful strategy than focusing on the Gospel alone that calls for welcoming and caring for the stranger in need.