‘Beyond Boundaries or Best Practice’ Prayer in Clinical Mental Health Care: Opinions of Professionals and Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Prayer with a religious patient can have a powerful positive effect and strengthen the therapeutic alliance. This, however, can be a dangerous intervention and should never occur until the psychiatrist has a complete understanding of the patient’s religious beliefs and prior experiences with religion. Prayer should only be done if the patient initiates a request for it, the psychiatrist feels comfortable doing so, and the religious backgrounds of patient and psychiatrist are similar. Even if all the right conditions are present, there will be some patients for whom prayer would be too intrusive, too personal and may violate delicate professional boundaries. Prayer should never be a matter of routine. The timing and intention must be planned out carefully with clear goals in mind”..

2. Methods

2.1. Sample/Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Characteristics of the Sample

3. Results

3.1. Mental Health Professionals

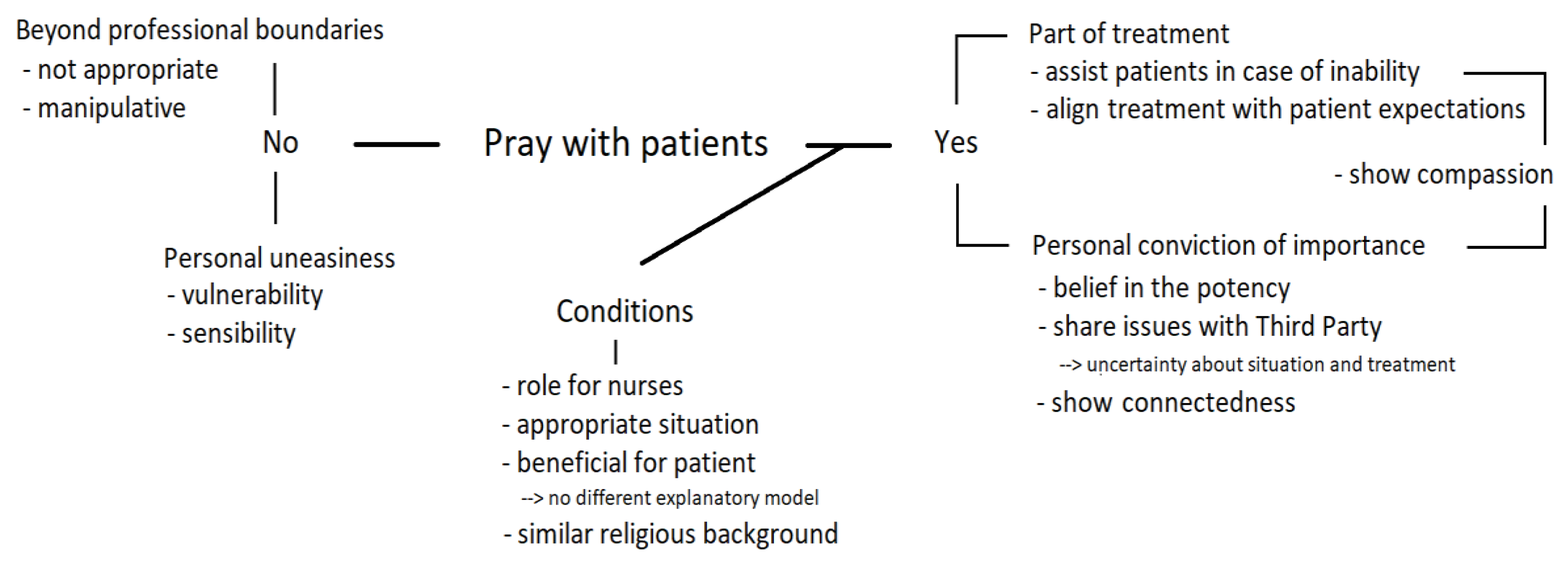

3.1.1. Reasons for and against Prayer with Patients

“I can imagine that it may give some relief … to give words to it, pronounce it and bring it to God in this way. That may be facilitating and releasing”.(CC8, social worker)

“I think prayer is like… well I am going to express to God… No, I think this is manipulative, I would never do such a thing”. And when asked about colleagues practicing prayer with patients: “Deep inside my heart, I think, they ought not to do so”.(CC4, social worker)

“As a practitioner, I think it to be very complicated. Because it is very personal… So when a patient asks me to pray, well (…) You are making yourself vulnerable and that would hinder me. Prayer is so much colored by personal convictions, I think that can be very delicate”.(CC2, practitioner)

3.1.2. A Role for Nurses?

“They are more close to patients, because they are with patients during the whole day and use to join their daily routine. Like someone having a need for much care, heading off to bed and then a nurse present and saying a prayer, well I think that suits in the nursing plan. When someone is unable to pray or has a need for it”.(CC2, practitioner)

“There is a man, being very depressive. To pray is impossible for him (…). In such a case I consider it to be my task to do it. It’s not that his faith depends on his prayer, but I can imagine his relief to have things expressed, to have words that can be brought to God”.(CC9, nurse)

3.1.3. Conditions

“Well, when I entered the clinic she was ready with a list of points to pray for. At a certain moment I said: well, now you can do it yourself. Right, so she did”.(CC6, nurse)

“It’s about… either or not evangelize, you know. Imagine, you are of a protestant church and so is the patient, and it happens that you could pray together when things are so hard. I am not against it. However, I always say: you should be able to find it in the daily report (…). The practitioner may question it and estimate whether or not it would be beneficial for the patient, or that the patient would get more feelings of guilt from it”.(SC9, nurse)

3.2. Mental Health Patients

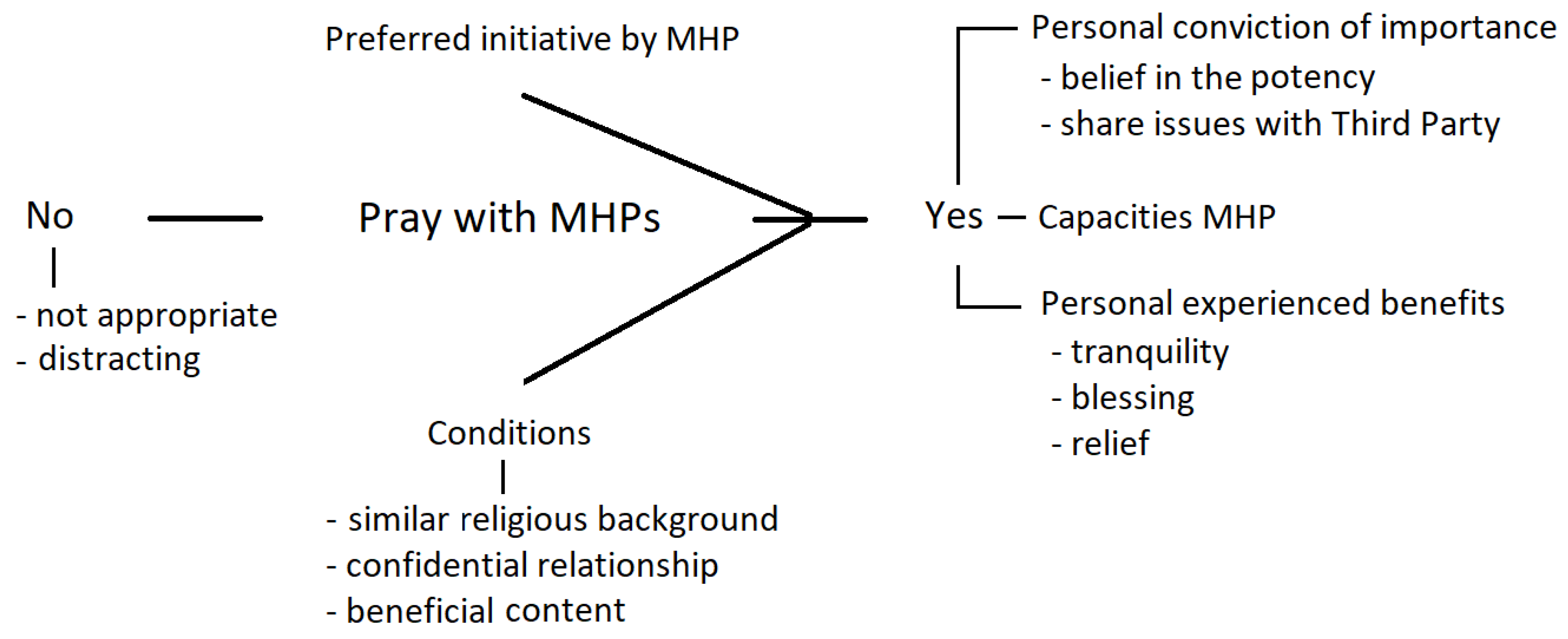

3.2.1. Importance and Benefits

“Possibly the knowledge you bring things to God. Aloud. And you ask God to join, really. You may know it by heart, but when you express it… it’s more substantial. Someone else expressing things for you. And I must say, often I experience tranquility and blessing by it. Not always, but often. Whether that is psychological… I don’t know, but it helps”.(Pt CC12)

“I really could imagine that it would help... when you’re down and that there happens to be someone with you, who in a safe atmosphere prays with you, or talks…”(Pt SC15)

“I think smart people are working here and they can pray very well, so express things in a good way. I think there is a power in that”.(Pt CC3)

“Just what I say, starting a clinical stay for example, it would be very good when someone else will pray with you for it. Like, we are here now, You are seeing us, will You help us during the coming months. I would have appreciated that. Someone approaching you, saying well it’s terrible for you being here alone, knowing nobody else. It’s like being thrown in the deep water and I want to bring that to God, together with you. Really, I would have very much appreciated that”.(Pt CC10)

3.2.2. Conditions

“You cannot haphazardly do such a thing, I mean, you should know each other quite well, at least that is what I think, before you start doing so (praying together, JN)”.(Pt SC16)

“It depends on how they pray, you know. If it is very heavy… you may bring patients further in the dark (laughs), but if the prayer is full of hope (…). Look, (…) you can pray for healing, you can bless somebody, it’s really a different type of stuff, what you are going to pray. You bring your own vison over (…). It’s no church here”.(Pt CC15)

3.2.3. Possible Objections

“They did not pray with me or so… and I did not think that appropriate in this place”.(Pt SC8)

“I found it kind of a distraction, from what really mattered (experience in the CC, JN). I never dared to say something against it, because I thought that would have been extra sinful. At least it did not go about my real problems, what I really was thinking. (…) It was kind of ‘double’, the atmosphere was familiar”.(Pt SC17)

“Because, despite my doubts and cares, I am a motivated Christian. And the practitioners as well, at least I may expect that. So it should be possible. But I understand that… well maybe a special board should consider it, but I do not rule it out. (…). At the same time there are snags. Whether it is good, professionally, with regard to distance, reticence, relationship. I don’t know. But I don’t say it should not happen”.(Pt CC14)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ameling, Ann. 2000. Prayer: An ancient healing practice becomes new again. Holistic Nursing Practice 14: 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, Chittaranjan, and Rajiv Radhakrishnan. 2009. Prayer and healing: A medical and scientific perspective on randomized controlled trials. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 51: 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronowitz, Teri, and Jacqueline Fawcett. 2016. Thoughts about social issues: A neuman systems model perspective. Nursing Science Quarterly 29: 173–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, Tom, and James Childress. 2019. Principles of biomedical ethics: Marking its fortieth anniversary. The American Journal of Bioethics: AJOB 19: 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, Stephanie Winkeljohn, Patrick Pössel, Benjamin D. Jeppsen, Annie C. Bjerg, and Don T. Wooldridge. 2015. Disclosure during private prayer as a mediator between prayer type and mental health in an adult christian sample. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 540–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curlin, Farr A., Ryan E. Lawrence, Shaun Odell, Marshall H. Chin, John D. Lantos, Harold G. Koenig, and Keith G. Meador. 2007. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: Psychiatrists’ and other physicians’ differing observations, interpretations, and clinical approaches. The American Journal of Psychiatry 164: 1825–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, Russell. 2007. The importance of spirituality in medicine and its application to clinical practice. The Medical Journal of Australia 186: S57–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dein, Simon, Christopher C. H. Cook, Andrew Powell, and Sarah Eagger. 2010. Religion, spirituality, and mental health. The Psychiatrist 34: 63–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiJoseph, Josephine, and Roberta Cavendish. 2005. Expanding the dialogue on prayer relevant to holistic care. Holistic Nursing Practice 19: 147–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durfee-Fowler, M. 2003. Form prayer and nursing care: Christian perspectives. Holistic Nursing Practice 17: 239–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Satu, and Helvi Kyngäs. 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, Richard J. 1992. Prayer: Finding the Heart’s True Home. San Franciso: Harper San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- French, Charlotte, and Aru Narayanasamy. 2011. To pray or not to pray: A question of ethics. British Journal of Nursing 20: 1198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, Eugene B., Angela L. Wadsworth, and Terry D. Stratton. 2002. Religion, spirituality, and mental health. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190: 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, Cheryl Ann. 2018. Complimentary care: When our patients request to pray. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 1179–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguelet, Philippe, Sylvia Mohr, Carine Betrisey, Laurence Borras, Christiane Gillieron, Adham Mancini Marie, Isabelle Rieben, Nader Perroud, and Pierre-Yves Brandt. 2011. A randomized trial of spiritual assessment of outpatients with schizophrenia: Patients’ and clinicians’ experience. Psychiatric Services 62: 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2008. Religion and mental health: What should psychiatrists do? Psychiatric Bulletin 32: 201–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, Kevin L., and Daniel N. McIntosh. 2008. Meaning, God, and prayer: Physical and metaphysical aspects of social support. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 11: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, Sylvia Dianne. 2005. The duty of nurses to meet patients’ spiritual and/or religious needs. British Journal of Nursing 14: 220–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Ruth. 2003. The use of prayer in spiritual care. The Australian Journal of Holistic Nursing 10: 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lukoff, David, Francis Lu, and Robert Turner. 1992. Toward a more culturally sensitive DSM-IV. psychoreligious and psychospiritual problems. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180: 673–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinuz, Marco, Anne-Véronique Dürst, Mohamed Faouzi, Daniel Pétremand, Virginie Reichel, Barbara Ortega, Gérard Waeber, and Peter Vollenweider. 2013. Do you want some spiritual support? different rates of positive response to chaplains’ versus nurses’ offer. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: JPCC 67: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, Kevin S., Glen I. Spielmans, and Jason T. Goodson. 2006. Are there demonstrable effects of distant intercessory prayer? A meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 32: 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, Kathy, and Elizabeth Johnston Taylor. 2018. Hospitalized patients’ responses to offers of prayer. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 279–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minton, Mary E., Mary Isaacson, and Deborah Banik. 2016. Prayer and the registered nurse (PRN): Nurses’ reports of ease and dis-ease with patient-initiated prayer request. Journal of Advanced Nursing 72: 2185–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, Jacob B., Jesse Owen, Jeffrey C. Valentine, Stephanie Winkeljohn Black, Tyler C. Halford, Stephanie E. Parazak, Stephanie Budge, and Mark Hilsenroth. 2018. Therapeutic alliance, empathy, and genuineness in individual adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research 28: 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwehand, Eva, Hanneke Muthert, Hetty Zock, Hennie Boeije, and Arjan Braam. 2018. Sweet delight and endless night: A qualitative exploration of ordinary and extraordinary religious and spiritual experiences in bipolar disorder. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 28: 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennybaker, Steven, Patrick Hemming, Durga Roy, Blair Anton, and Margaret S. Chisolm. 2016. Risks, Benefits, and recommendations for pastoral care on inpatient psychiatric units: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 22: 363–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Being Christian in Western Europe. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2018/05/29/being-christian-in-western-europe/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Poloma, Margaret M., and George Horace Gallup. 1991. Varieties of Prayer: A Survey Report. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, Rob, and Christopher C. H. Cook. 2011. Praying with a patient constitutes a breach of professional boundaries in psychiatric practice. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science 199: 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, Rob, Robert Higgo, Gill Strong, Gordon Kennedy, Sue Ruben, Richard Barnes, Peter Lepping, and Paul Mitchell. 2008. Religion, spirituality and professional boundaries. The Psychiatrist 32: 356–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilka, Bernard, and Kevin L. Ladd. 2013. The Psychology of Prayer: A Scientific Approach. New York and London: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, Melinda A., Amber L. Bush, Mary E. Camp, John P. Jameson, Laura L. Phillips, Catherine R. Barber, Darrell Zeno, James W. Lomax, and Jeffrey A. Cully. 2011. Older adults’ preferences for religion/spirituality in treatment for anxiety and depression. Aging & Mental Health 15: 334–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Elizabeth Johnston. 2003. Prayer’s clinical issues and implications. Holistic Nursing Practice 17: 179–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Allison, Peter Sainsbury, and Jonathan Craig. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Hanneke Schaap-Jonker, Carmen Schuhmann, Christa Anbeek, and Arjan W. Braam. 2018. The ‘religiosity gap’ in a clinical setting: Experiences of mental health care consumers and professionals. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 21: 737–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Hanneke Schaap-Jonker, Christina Hennipman-Herweijer, Christa Anbeek, and Arjan W. Braam. 2019. Patients’ Needs of Religion/Spirituality Integration in Two Mental Health Clinics in the Netherlands. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 40: 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Hanneke Schaap-Jonker, Gerlise Westerbroek, Christa Anbeek, and Arjan W. Braam. 2020a. Conversations and beyond: Religious/Spiritual care needs among clinical mental health patients in the netherlands. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208: 524–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Hanneke Schaap-Jonker, Christa Anbeek, and Arjan W. Braam. 2020b. Religious/spiritual care needs and treatment alliance among clinical mental health patients. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Währisch-Oblau, Claudia. 2011. Material salvation: Healing, Deliverance, and ‘Breakthrough’ in African Migrant Churches in Germany. In Global Pentecostal and Charismatic Healing. Edited by Candy Gunther Brown. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow, Gerald R., and Betty Wehtje Winslow. 2003. Examining the ethics of praying with patients. Holistic Nursing Practice 17: 170–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | On the one hand, prayer can be expected to help due to direct intervention by God—this expectation could be regarded as religious (and hence related to a religious explanatory model of mental disease). In contrast, there is the biomedical and psychological approach, as required and expected in a mental health clinic (this is a secular, scientific or naturalistic explanatory model). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, J.C.; Braam, A.W.; Anbeek, C.; Schaap-Jonker, H. ‘Beyond Boundaries or Best Practice’ Prayer in Clinical Mental Health Care: Opinions of Professionals and Patients. Religions 2020, 11, 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100492

van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse JC, Braam AW, Anbeek C, Schaap-Jonker H. ‘Beyond Boundaries or Best Practice’ Prayer in Clinical Mental Health Care: Opinions of Professionals and Patients. Religions. 2020; 11(10):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100492

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Joke C., Arjan W. Braam, Christa Anbeek, and Hanneke Schaap-Jonker. 2020. "‘Beyond Boundaries or Best Practice’ Prayer in Clinical Mental Health Care: Opinions of Professionals and Patients" Religions 11, no. 10: 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100492

APA Stylevan Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, J. C., Braam, A. W., Anbeek, C., & Schaap-Jonker, H. (2020). ‘Beyond Boundaries or Best Practice’ Prayer in Clinical Mental Health Care: Opinions of Professionals and Patients. Religions, 11(10), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100492