Educational Potentials of Flipped Learning in Intercultural Education as a Transversal Resource in Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Justification and Objectives

- To determine the effect of the traditional methodology on learning intercultural competences in students;

- To know the effect of the flipped methodology on learning intercultural competences;

- To determine the impact of the flipped methodology on the academic results obtained;

- To determine the strength of the possible differences found.

1.2. Intervention Description

- To know the causes and repercussions of the migratory movements of society;

- To assimilate cultural diversity as a potential feature of society.;

- To foster the social inclusion of all people in today’s society;

- To develop social interactions based on respect, empathy, coexistence and democratic behavior;

- To export to citizens social and civic values for the development of peace;

- To foster respect for human rights in a society in constant transformation.

2. Materials and Methods

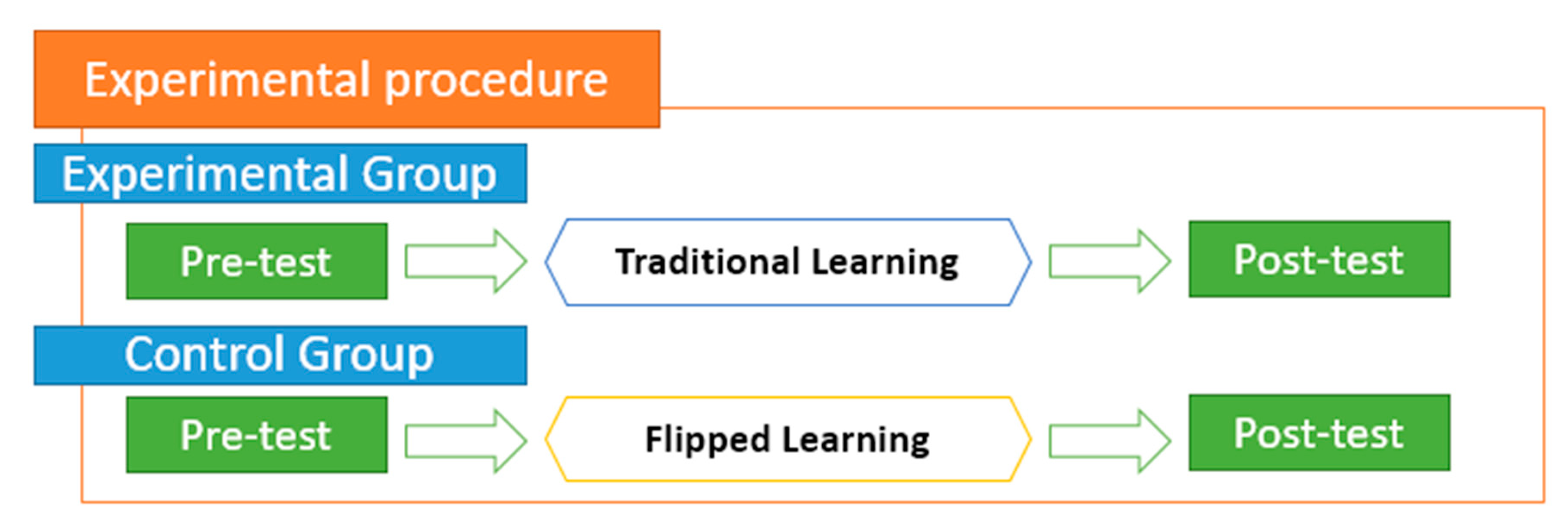

2.1. Research Design and Data Analysis

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Reliability Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

3.3. Inferential Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alderman, Harold, and Derek D. Headey. 2017. How Important Is Parental Education for Child Nutrition? World Development 94: 448–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Rodriguez, María Dolores, María del Carmen Bellido-Márquez, and Pedro Atencia-Barrero. 2019. Enseñanza Artística Mediante TIC En La Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED) 1: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, Georgia, Eva Aguaded-Ramírez, and María Elena Parra-González. 2019. Analysis of Process of Adaptation and Acculturation of Refugee Women in Spain. In El valor de la educacion en una Sociedad culturalmente diversa. Almería: EDUHEM, pp. 133–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area-Moreira, Manuel, Víctor Hernández-Rivero, and Juan José Sosa-Alonso. 2016. Models of educational integration of ICTs in the classroom. Comunicar 24: 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, Aguavil, Jacqueline Marilú, and Ramiro Andrés Andino Jaramillo. 2018. Necesidades Formativas de Docentes de Educación Intercultural Tsáchila. Alteridad 14: 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awidi, Isaiah T., and Mark Paynter. 2019. The Impact of a Flipped Classroom Approach on Student Learning Experience. Computers & Education 128: 269–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belattar, Abdelouahed. 2014. Menores Migrantes No Acompañados: Víctimas o Infractores. Revista Sobre La Infancia y La Adolescencia 7: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berea, Guadalupe Aurora Maldonado, Janet García González, and Begoña Esther Sampedro Requena. 2019. El Efecto de Las TIC y Redes Sociales En Estudiantes Universitarios. RIED Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 22: 153–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Jonathan, and Aaron Sams. 2012. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Eugene: International Society for Technology in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Bharali, Reecha. 2014. Enhancing Online Learning Activities for Groups in Flipped Classrooms. In Learning and Collaboration Technologies. Technology-Rich Environments for Learning and Collaboration. Edited by Panayiotis Zaphiris and Andri Ioannou. Cham: Springer International Publishing, vol. 8524, pp. 269–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognar, Branko, Marija Sablić, and Alma Škugor. 2019. Flipped Learning and Online Discussion in Higher Education Teaching. In Didactics of Smart Pedagogy. Edited by Linda Daniela. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 371–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, Amaia, and Iriana Santos-González. 2017. Menores extranjeros no acompañados en España: necesidades y modelos de intervención. Psychosocial Intervention 26: 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero Almenara, Julio, and Julio Barroso Osuna. 2018. Los Escenarios Tecnológicos En Realidad Aumentada (RA): Posibilidades Educativas. Aula Abierta 47: 327–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos Sánchez, Almudena, Cristina Sánchez Romero, and José Fernando Calderero Hernández. 2017. Nuevos Modelos Tecnopedagógicos. Competencia Digital de Los Alumnos Universitarios. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 19: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyr, Wen-Li, Pei-Di Shen, Yi-Chun Chiang, Jau-Bi Lin, and Chia-Wen Tsai. 2017. Exploring the Effects of Online Academic Help-Seeking and Flipped Learning on Improving Students’ Learning. Educational Technology & Society 20: 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ciges, Auxiliadora Sales. 2012. Creando Redes Para Una Ciudadanía Crítica Desde La Escuela Intercultural Inclusiva. Revista de Educación Inclusiva 5: 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas, René Edmundo, Angelino Feliciano, Antonio Alarcón, Arnulfo Catalán, and Gustavo Adolfo Alonso. 2019. La Integración de Herramientas TIC al Perfil Del Ingeniero En Computación de La Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, México. Virtualidad, Educación y Ciencia 10: 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, Mercedes. 2017. Menores refugiados: impacto psicológico y salud mental. Apuntes de Psicología 35: 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, Gunther. 2017. Interculturalidad: Una aproximación antropológica. Perfiles Educativos 39: 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Juan Carlos, and Paula Andrea Sánchez. 2018. Limitaciones conceptuales para la evaluación de la competencia digital. Revista Espacios 39: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Natalia González, and Gustavo Adolfo Carrillo Jácome. 2016. El Aprendizaje Cooperativo y la Flipped Classroom: Una pareja ideal mediada por las TIC. Aularia: Revista Digital de Comunicación 5: 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Batanero, José María, and José Manuel Aguilar Parra. 2016. Competencias docentes interculturales del profesorado de educación física de Andalucia, España. Movimento 22: 753–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Rosemary, Bella Ross, Richard LaFerriere, and Alex Maritz. 2017. Flipped Learning, Flipped Satisfaction, Getting the Balance Right. Teaching & Learning Inquiry 5: 114–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, Andrés Escarbajal, Celia Pardo Marhuenda, and Mohamed Chamseddine Habib Allah. 2017. La realidad socioeducativa intercultural del alumnado de origen migrante en educación secundaria. Algunos aspectos relevantes. Interacções 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett-Rucks, Paula. 2017. Fostering Learners’ Intercultural Competence with CALL. Oreign Language Education Research 20: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- He, Wenliang, Amanda Holton, George Farkas, and Mark Warschauer. 2016. The Effects of Flipped Instruction on Out-of-Class Study Time, Exam Performance, and Student Perceptions. Learning and Instruction 45: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sampieri, Roberto, Carlos Fernández Collado, Pilar Baptista Lucio, Sergio Méndez Valencia, and Christian Paulina Mendoza Torres. 2014. Metodología de la Investigación. Mexico: McGrawHill. [Google Scholar]

- Huan, Chenglin. 2016. A Study on Digital Media Technology Courses Teaching Based on Flipped Classroom. American Journal of Educational Research 4: 264–67. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Biyun, Khe Foon Hew, and Chung Kwan Lo. 2019. Investigating the Effects of Gamification-Enhanced Flipped Learning on Undergraduate Students’ Behavioral and Cognitive Engagement. Interactive Learning Environments 27: 1106–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Gwo-Jen, Chiu-Lin Lai, and Siang-Yi Wang. 2015. Seamless Flipped Learning: A Mobile Technology-Enhanced Flipped Classroom with Effective Learning Strategies. Journal of Computers in Education 2: 449–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Gwo-Jen, Ting-Chia Hsu, Chiu-Lin Lai, and Ching-Jung Hsueh. 2017. Interaction of Problem-Based Gaming and Learning Anxiety in Language Students’ English Listening Performance and Progressive Behavioral Patterns. Computers & Education 106: 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juaristi, Maddalen Epelde. 2017. Nuevas Estrategias Para La Integración Social de Los Jóvenes Migrantes No Acompañados. Revista Sobre La Infancia y La Adolescencia 13: 57–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karabulut-Ilgu, Aliye, Nadia Jaramillo Cherrez, and Lesya Hassall. 2018. Flipping to Engage Students: Instructor Perspectives on Flipping Large Enrolment Courses. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 34: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, Myint Swe, Nagla Ali, and Ernest Afari. 2017. Exploring Relationships among TPACK Constructs and ICT Achievement among Trainee Teachers. Education and Information Technologies 22: 1605–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, Kurt, and Petra Hoffstaedter. 2017. Learner Agency and Non-Native Speaker Identity in Pedagogical Lingua Franca Conversations: Insights from Intercultural Telecollaboration in Foreign Language Education. Computer Assisted Language Learning 30: 351–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Jung, and Hyung Woo. 2017. The Impact of Flipped Learning on Cooperative and Competitive Mindsets. Sustainability 10: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, Viola, Ken Brown, Tatiana Bystrova, and Evgueny Sinitsyn. 2018. Russian Perspectives of Online Learning Technologies in Higher Education: An Empirical Study of a MOOC. Research in Comparative and International Education 13: 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jihyun, Taejung Park, and Robert Otto Davis. 2018. What Affects Learner Engagement in Flipped Learning and What Predicts Its Outcomes?: FL Engagement and Outcomes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva Olivencia, Juan José. 2017. Estilos de Aprendizaje y Educación Intercultural En La Escuela/Learning Styles and Intercultural Education at School. Tendencias Pedagógicas 29: 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shengru, Shinobu Yamaguchi, Javzan Sukhbaatar, and Jun-ichi Takada. 2019. The Influence of Teachers’ Professional Development Activities on the Factors Promoting ICT Integration in Primary Schools in Mongolia. Education Sciences 9: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Taotao, John Cummins, and Michael Waugh. 2017. Use of the Flipped Classroom Instructional Model in Higher Education: Instructors’ Perspectives. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 29: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Belmonte, Jesús, Santiago Pozo Sánchez, and María José Del Pino Espejo. 2019. Projection of the Flipped Learning Methodology in the Teaching Staff of Cross-Border Contexts. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 8: 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Quintero, José Luis, Alfonso Pontes-Pedrajas, and Marta Varo-Martínez. 2019. Las TIC en la enseñanza científico-técnica hispanoamericana: Una revisión bibliográfica. Digital Education Review, 229–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvarez, Isabel, and Alicia Lajo Muñoz. 2018. Estudio Neuropsicológico de La Funcionalidad Visual, Las Estrategias de Aprendizaje y La Ansiedad En El Rendimiento Académico. Aula Abierta 47: 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengual Andrés, Santiago, Jesús López Belmonte, Arturo Fuentes Cabrera, and Santiago Pozo Sánchez. 2019. Modelo Estructural de Factores Extrínsecos Influyentes En El Flipped Learning. Educación XX1 23: 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou, Kleopatra, Despoina Akriotou, and Vasilis Gialamas. 2019. Early Reading Skills in English as a Foreign Language Via ICT in Greece: Early Childhood Student Teachers’ Perceptions. Early Childhood Education Journal 47: 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, Frederico, Eduardo Shigueo, and Humberto Abdala. 2018. Collaborative Teaching and Learning Strategies for Communication Networks. The International Journal of Engineering Education 34: 527–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nortvig, Anne-Mette, Anne Kristine Petersen, and Søren Hattesen Balle. 2018. A Literature Review of the Factors Influencing E-Learning and Blended Learning in Relation to Learning Outcome, Student Satisfaction and Engagement. Electronic Journal of E-Learning 16: 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ogan, Amy, Vincent Aleven, and Christopher Jones. 2009. Advancing Development of Intercultural Competence Through Supporting Predictions in Narrative Video. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 19: 267–88. [Google Scholar]

- Parra-González, María Elena, and Adrián Segura-Robles. 2019. Traducción y Validación de La Escala de Evaluación de Experiencias Gamificadas (GAMEX). Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Sara, Joana Fillol, and Pedro Moura. 2019. Young people learning from digital media outside of school: The informal meets the formal. Comunicar 27: 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Carmen Inés Báez, and Clifton Eduardo Clunie Beaufond. 2019. Una Mirada a La Educación Ubicua. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 22: 325–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, Ana. 2018. Uso de smartphones y redes sociales en alumnos/as de Educación Primaria. Revista Prisma Social 1: 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, Paul R., Dale H. Schunk, Margarita Limón Luque, and Juan Antonio Huertas Martínez. 2006. Motivación en Contextos Educativos: Teoría, Investigación y Aplicaciones. Madrid: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, Nacarid. 2011. Diseños Experimentales En Educación. Revista de Pedagogía 32: 147–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Déborah Martín, Mª Magdalena Sáenz de Jubera, Raúl Santiago Campión, and Edurne Chocarro de Luis. 2016. Diseño de Un Instrumento Para Evaluación Diagnóstica de La Competencia Digital Docente: Formación Flipped Classroom. Didáctica, Innovación y Multimedia 1: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, Daniel Garrote, Juan Ángel Arenas Catillejo, and Sara Jiménez-Fernández. 2018. Las Tic Como Herramienta de Desarrollo de La Competencia Intercultural. EDMETIC 7: 134–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, Claudia Grau, and María Fernández Hawrylak. 2016. La Educación Del Alumnado Inmigrante En España. Arxius de Sociologia 34: 141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sacavino, Vera Maria, and Susana Candau. 2014. Derechos humanos, educación, interculturalidad: construyendo prácticas pedagógicas para la paz. Ra Ximhai 10: 205–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, Nor Syazwani Mat, Aidah Abdul Karim, M. A. T. Mazzlida, Siti Zuraida Abdul Manaf, Noor Fazrienee J. Z. Nun Ramlan, and Analisa Hamdan. 2019. An Evaluation of Content Creation for Personalised Learning Using Digital ICT Literacy Module among Aboriginal Students (MLICT-OA). Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 20: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Ester, and Antonio Tirso. 2016. La educación intercultural como principal modelo educativo para la integración social de los inmigrantes. Cadernos de Dereito Actual 4: 139–51. [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Robles, Adrián, and María Elena Parra-González. 2019. Analysis of Teachers’ Intercultural Sensitivity Levels in Multicultural Contexts. Sustainability 11: 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Wen-Ling, and Chun-Yen Tsai. 2016. Students’ Perception of a Flipped Classroom Approach to Facilitating Online Project-Based Learning in Marketing Research Courses. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola Martínez, Tomás, Inmaculada Aznar Díaz, José María Romero Rodríguez, and Antonio-Manuel Rodríguez-García. 2018. Eficacia Del Método Flipped Classroom En La Universidad: Meta-Análisis de La Producción Científica de Impacto. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio En Educación 17: 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solbes, Victor M. Martín, and Santiago Ruiz Galacho. 2018. La Educación Intercultural Para Una Sociedad Diversa. Miradas Desde La Educación Social y La Reflexión Ética. RES: Revista de Educación Social 27: 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Thai, Ngoc Thuy Thi, Bram De Wever, and Martin Valcke. 2017. The Impact of a Flipped Classroom Design on Learning Performance in Higher Education: Looking for the Best “Blend” of Lectures and Guiding Questions with Feedback. Computers & Education 107: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, María, and Beatriz Manzano. 2016. La Educación inclusiva intercultural en Latinoamericana. Análisis legislativo. Revista de Educación Inclusiva 9: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tourón, Javier, and Raúl Santiago. 2015. El Modelo Flipped Learning y El Desarrollo Del Talento En La Escuela = Flilpped Learning Model and the Development of Talent at School. Revista de Educación 368: 174–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, Wai S., Lai Y. A. Choi, and Wing S. Tang. 2019. Effects of Video-Based Flipped Class Instruction on Subject Reading Motivation: Flipped Class Instruction. British Journal of Educational Technology 50: 385–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Roy, Rob, and Bieke Zaman. 2019. Unravelling the Ambivalent Motivational Power of Gamification: A Basic Psychological Needs Perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 127: 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Ping, and Shi Qian. 2018. Application of Flipped Classroom Teaching Model in Intercultural Communication Courses in Universities and Colleges in Yunnan Province. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education (ICSSHE 2018). Sanya: Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Atike, and Fikret Soyer. 2018. Effect of Physical Education and Play Applications on School Social Behaviors of Mild-Level Intellectually Disabled Children. Education Sciences 8: 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Hiroki. 2016. Perceived Usefulness of ‘Flipped Learning’ on Instructional Design for Elementary and Secondary Education: With Focus on Pre-Service Teacher Education. International Journal of Information and Education Technology 6: 430–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Zamzami, H. Habiburrahim, Safrul Muluk, and Cut Muftia Keumala. 2019. How Do Students Become Self-Directed Learners in the EFL Flipped-Class Pedagogy? A Study in Higher Education. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics 8: 678–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | An oral language with numerous groups of mutually intelligible dialect varieties coming from the Arabic language. |

| 2 | This corresponds to compulsory education for students between 15–16 years old. |

| Groups | Boys n (%) | Girls n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 16 (53.33) | 14 (46.67) | 30 (50) |

| Control group | 10 (33.33) | 20 (66.66) | 30 (50) |

| Subtotal | 26 (40) | 34 (60) | 60 (100) |

| Alpha (α) | CR * | AVE ** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Achievement | 0.85 | 0.910 | 0.753 |

| Learning Anxiety | 0.89 | 0.823 | 0.615 |

| Motivation | 0.91 | 0.855 | 0.755 |

| Autonomy | 0.86 | 0.845 | 0.653 |

| Traditional Learning (Control group) | ||

| Pre-test | Post-test | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Learning Achievement | ---- | 4.10 (1.11) |

| Learning Anxiety | 4.78 (0.82) | 4.70 (0.91) |

| Motivation | 2.69 (1.13) | 2.79 (0.61) |

| Autonomy | 3.00 (0.72) | 3.50 (0.62) |

| Flipped learning (Experimental group) | ||

| Pre-test | Post-test | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Learning Achievement | ---- | 4.9 (1.21) |

| Learning Anxiety | 4.60 (0.77) | 3.13 (0.82) |

| Motivation | 2.50 (1.03) | 4.55 (1.13) |

| Autonomy | 4.01 (0.62) | 4.98 (0.72) |

| Mean Rank | U | Z | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-test | Traditional | 40.23 | 151.000 | −1.515 | 0.049 | 0.11 |

| Flipped | 60.82 | |||||

| Mean Rank | U | Z | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Pre-test | 55.13 | 231.000 | −1.405 | 0.061 | -- |

| Post-test | 57.19 | |||||

| Flipped | Pre-test | 50.23 | 201.800 | −2.454 | 0.041 | 0.10 |

| Post-test | 39.17 | |||||

| Mean Rank | U | Z | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Pre-test | 41.03 | 181.500 | −2.231 | 0.093 | -- |

| Post-test | 43.05 | |||||

| Flipped | Pre-test | 42.83 | 231.100 | −2.111 | 0.039 | 0.15 |

| Post-test | 23.31 | |||||

| Mean Rank | U | Z | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Pre-test | 41.38 | 121.500 | −1.931 | 0.081 | -- |

| Post-test | 39.55 | |||||

| Flipped | Pre-test | 45.98 | 101.300 | −1.128 | 0.025 | 0.21 |

| Post-test | 54.26 | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuentes Cabrera, A.; Parra-González, M.E.; López Belmonte, J.; Segura-Robles, A. Educational Potentials of Flipped Learning in Intercultural Education as a Transversal Resource in Adolescents. Religions 2020, 11, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010053

Fuentes Cabrera A, Parra-González ME, López Belmonte J, Segura-Robles A. Educational Potentials of Flipped Learning in Intercultural Education as a Transversal Resource in Adolescents. Religions. 2020; 11(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuentes Cabrera, Arturo, María Elena Parra-González, Jesús López Belmonte, and Adrián Segura-Robles. 2020. "Educational Potentials of Flipped Learning in Intercultural Education as a Transversal Resource in Adolescents" Religions 11, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010053

APA StyleFuentes Cabrera, A., Parra-González, M. E., López Belmonte, J., & Segura-Robles, A. (2020). Educational Potentials of Flipped Learning in Intercultural Education as a Transversal Resource in Adolescents. Religions, 11(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010053