Abstract

This article considers the major cycles of illumination in two Books of Hours belonging to Thomas Butler, seventh Earl of Ormond (c.1424–1515). The article concludes that the iconography of the two manuscripts reflects the personal and familial piety of the patron and was designed to act as a tool in the practice of devotion.

Keywords:

private devotion; Books of Hours; illumination; Holy Trinity; pictorial cycles; Butlers; Ormond Item I will that my sawter boke covered with whyte lether and my name writtin with myn owne hand in thende of the same wych is at my lodging in London shalbe layd and fyxed with a cheyne of iron at my tombe wych is ordeyned for me in the […] church of Saint Thomas Acon there to remayne for the servyce of God in the said church the better to be hadde and done by suche persones as shalbe disposed to occupye and loke upon the same boke.(will of Thomas Butler 299–300)

Shortly before his death, Sir Thomas Butler, seventh Earl of Ormond (c.1424–1515), prepared his last will and testament including the above stipulation that his Psalter bearing his name be chained to his tomb in a public demonstration of his personal piety. While the Psalter itself has not survived, the provisions of his will present an image of Butler as an active and conscientious participant in both private devotion and his own commemoration, and his surviving Books of Hours offer a personal reflection of his piety and demonstrate the importance of the material object in his practice of devotion.

Sir Thomas Butler, seventh Earl of Ormond (c.1424–1515), was the son of James Butler, fourth Earl of Ormond (the White Earl), and his wife Joan, daughter of William Beauchamp, Lord Abergavenny. Though born in Ireland, Butler spent most of his life in England and became a significant landholder there from the time of his marriage to Anne Hankeford in 1445.1 Butler had two daughters from his first marriage, Anne and Margaret, the latter of whom was mother to Thomas Boleyn, first Earl of Wiltshire and father of Anne Boleyn. Between 1495 and 1497, he married the twice widowed Lora Berkeley with whom he had a daughter, Elizabeth. Support for the Lancastrian cause and the attempt of his brother, John, the sixth Earl, to raise a Lancastrian revolt in Ireland saw Butler attainted twice and go into exile in the court of Margaret of Anjou in the duchy of Bar. Upon the death of his brother in 1477, Butler acceded to his titles and estates and was restored his English lands in November 1485. Butler attended the coronation of Richard III in 1483 where he was knighted, held positions on the privy councils of both Richard III and Henry VII, appointed lord chamberlain to Catherine of Aragon in 1509, acted as Ambassador to Brittany and Burgundy in 1491 and 1497 respectively, and is known to have been in France in the retinue of Henry VII in 1500 (Calendar of Ormond Deeds 1935, nos. 211 and 247; Beresford 1999; Cokayne 1945, pp. 131–32; Crawford [1994] 2002, p. 151; Fortescue 1869, vol. I p. 24; Sutton and Hammond 1983, p. 379). Butler died in August 1515 and was buried in the Church of St Thomas of Acre in London. At the time of his death, Butler was in possession of some seventy-two manors and diverse others lands in England, divided equally between his daughters Anne and Margaret, in addition to the Ormond lands and manors in Ireland which came under the control of a relative, Piers Butler, eighth Earl (Lodge 1754, vol. II p. 13).

I bequeth and recomend my soule unto allmyghty my maker and redemerto the moost glorius virgyn his mother our Lady Saint Mary and to the glorius martyr Saint Thomas and to all the holy colege of saintys in hevyn. And my body to be buryed in the churche of Saint Thomas Acon in London that is to wytt uppon the north syde of the hygh aulter if the high aulter in the said church where the sepulture of all mighty God is used yerely to be sett on Good Friday to thentent that by the merytes of his most precyous passion and glorius resurreccion […] I wyll ther be ordeyned and sett an epitahafe makyng memyery of me and the day and yere of my decesse. And this to be doon by the distrecyons of myn executors not for any pompe of the worled but only for a rememberance.(will of Thomas Butler 298)

The instructions left by Sir Thomas Butler in his will are quite revealing in terms of his concern for action and outcome. First having already ‘ordeyned’ his tomb to lie in St Thomas of Acre, it seems that the seventh Earl was concerned with tangible results and that the commemorative arrangements that he had negotiated were followed through. Butler stipulates that should he die on his Essex estate or anywhere within forty miles of London that his body should be transferred to St Thomas of Acre, but he also stipulates that should he die further afield that he should be interred ‘in holy sepulture wher it shall please allmyghty God to dispose of [him]’ (will of Thomas Butler 298).

The Church of St Thomas of Acre was established on the site of birthplace of the martyred St Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, in the parish of St. Mary Colechurch, by an order of hospitaller knights in 1227–1228. The church became a popular burial place for Londoners wishing to associate themselves with the martyr and from the thirteenth century onwards it was accorded various grants, donations, and chantries (see Keene and Harding 1987; Steer 2013; Sutton 2008). The association of the Earls of Ormond and the Church of St Thomas of Acre dates at least to the White Earl who became an important patron of the hospital due to his supposed familial ties with St Thomas and also seemingly a political alliance and business relationship with John Neel, Master of the Hospital (Matthew 1994, pp. 258n, 263, 279n, 406; Sutton 2008, pp. 202–5). The White Earl’s second wife, Joan, was interred there on her death in 1430 in the chapel of the Holy Cross. Her tomb was likely of considerable grandeur given it was included in the heraldic account of c.1504 and in John Stow’s Survey of London in 1603 (Calendar of Wills 1890, p. 506; Stow [1603] 1908, vol. I p. 269). The association with Becket was later developed in 1454 when James, Earl of Wiltshire and Ormond, claimed a blood relationship with St Thomas during a petition to Parliament and also offered the estate of Hulcott in Buckinghamshire to the hospital in order to endow a chantry for the chapel in which his mother was buried (Rotuli Parliamentorum 1767–1777, pp. 257, 491–95; Watney 1906, p. 138). This belief in kinship is thought to have arisen from one of two potential misidentifications. One source of confusion could be that between Archbishop Becket and Archbishop Hubert Walter who was the brother of Theobald, the first Walter or Butler in Ireland. The second suggestion is that Theobald Butler as Lord of Hely (Ely-O’Carroll) came to be confused with Theobald of Helles, nephew of St Thomas (Brooks 1956, p. 26; Carte 1851, vol. I pp. xxxiv–xxxvi; Keene and Harding 1987, pp. 490–517). Both the Ormond interest in the hospital church, as well as some of its traditional roles, continued past the dissolution of the monasteries. The will of James, ninth Earl of Ormond (†1546), requested he be buried at ‘St Thomas of Acres, somtyme so called, with others therles of Ormond’ and subsequently his son, Thomas, tenth Earl (†1614), in his will dated 1576 specified that if he were to die ‘within the realm of England then [his] body be buried in [his] father’s tomb at St Thomas of Dacres in London.’ Both men were ultimately interred along with their ancestors in the chancel of St Canice’s Cathedral in Kilkenny (Calendar of Ormond Deeds, vol IV no. 352 and vol V no. 288).

Precise instructions are also provided in Butler’s will for his commemoration. Butler provided for an obit for himself, his two wives, his parents, and his grandmother, Dame Jane Beauchamp, to be performed annually for seven years on the anniversary of his death. Furthermore, he adapted his parents’ annual chantry to include himself and his wives requesting that the names be ‘reherce[d]’ during the sermons. Butler requests that the tomb itself, be it in St Thomas of Acre or elsewhere, be situated next to the Easter sepulchre and that it bear an epitaph to record his memory and leaves funds for ‘torches and other lyghts and apparell’ to be brought to his tomb. The epitaph was later recorded by John Weever in his eighteenth-century account of Ancient Funeral Monuments (will of Thomas Butler 298–99; Weever 1767, p. 187).2 The appearance and commemorative nature of the tomb was obviously of some significance for Butler as it was relatively unusual for London testators to refer to the physical appearance of their tombs (Harding 1992; Steer 2013, pp. 159–69). Chaining his Psalter in which he had personally written his name to the tomb also ensured a physical and spiritual connection between individual, memory, and prayer: each time the Psalter was used the reader was encouraged to keep Butler in their prayers.

The various elements of Butler’s commemoration carry an expectation of performance—physical acts—to assist in and inspire commemoration and ultimately the salvation of the souls of Butler and his wives: ‘convey my body’, bring the lights, ‘reherce’ the names, ‘loke upon the […] boke’, keep in their prayers and masses. This same relationship between the public life of the material object, physical performance and commemorative or devotional response is also demonstrated in the more private aspects of Butler’s devotion and illumination of the two extant Books of Hours, known to have been associated with the Ormonds, mostly likely with Thomas Butler.

1. The Butler Books of Hours

Butler was responsible for the purchase and refurbishment of one, the Hours of the Earls of Ormond, London, British Library Harley MS 2887 [Harley], and the commissioning of a second Book of Hours, London, British Library Royal MS 2 B XV, which shall be referred to as ‘the Hours of Thomas Butler’ [Royal]. While Books of Hours, English manuscripts included, have been the subject of a number of publications in recent years (Duffy 2011; Reinburg 2012; Hindman and Marrow 2013; Morgan 2013; Kennedy 2014), the Butler manuscripts have received very little scholarly attention. Where the manuscripts have been the subject of discussion (Scott 1996), the focus has fallen on the inferior quality of the execution or peculiarity of the iconographical choices, rather than the creativity of the iconography, the motivation for and function of the illumination, and relationship of the manuscripts to the reader and devotional practice.

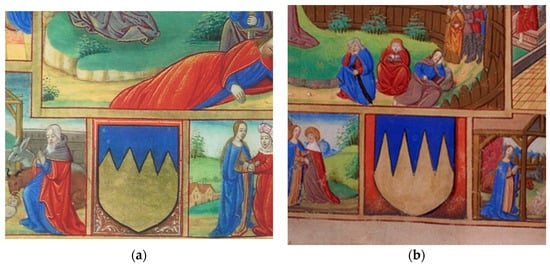

Today the Harley manuscript measures 27.5 × 18.5 cm in size and is illuminated with five full-page miniatures plus one incomplete, one small miniature, seven full pages offering pictorial cycles, sixteen historiated initials, seven fully bordered pages, and ten pages bordered on three sides. Marginal notes on f.1v of the Harley manuscript record three sets of births in 1467 and 1470, those of Angneta, George, John and Annas Gower of Crooked Lane in St Michael’s Parish. This suggests that the likely original owner was one Edward Gower of London. Of interest here however are only the English, or perhaps French-inspired, miniatures which were added considerably later: ff. 6v, 8v, 27v, 28v, 33v and 55v-58v. A further miniature, that on f.3v, was also a later addition but is considerably different from the others. Dutch in style, the image is associated with a group of artists known as the ‘Master of the Black Eyes’ and was likely imported along with the two folia directly following it (Scott 1996, vol. II pp. 299–302; Scott 1968, pp. 172, 176). One of the inserted folia, 28v, bears the blue and gold shield of the Butler family and the device is also to be found on f.15v of the Hours of Thomas Butler (Figure 1). The coat of arms is inserted as a preface to Matins in the Hours of the Virgin in both manuscripts. In her assessment of self-representation in late medieval art Alexa Sand notes that the insertion of the patron’s self-image at the invocation of Matins, ‘O Lord, open my mouth’, as in both the Hours of the Earls of Ormond and the Hours of Thomas Butler,3 rather than the opening of a penitential text, ‘O Lord, hear my prayer’ as in Psalm 101, carries an important emphasis on the ‘supplicant’s actions over God’s perceptions’ (Sand 2014, pp. 163–64). Associating the Butler arms with an active rather than passive appeal invites the reader to act upon seeing their self-image reflected on the page and to utter the words of the prayer.

Figure 1.

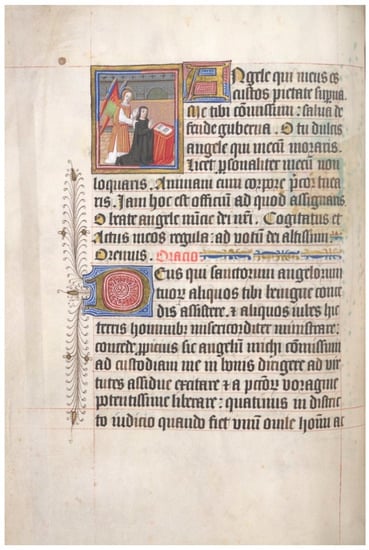

(a) Butler arms, The Hours of the Earls of Ormond, London, British Library Harley MS 2887, f.28v, (b) Butler arms, The Hours of Thomas Butler, London, British Library Royal MS 2 B XV, f.15v, © British Library Board.

The Royal manuscript measures 33 × 24 cm in size and is illuminated with six full-page miniatures some with floral borders, seven half-page miniatures, four full pages offering pictorial cycles, nineteen historiated initials, eight small miniatures and marginal scenes, a space left for an image, twenty-three fully bordered pages, two pages bordered on three sides, and extensive pen flourishing throughout. This represents a relatively lavish production for an English Book of Hours of the fifteenth century. Nigel Morgan has highlighted that few high-quality illuminated manuscripts were produced after c.1430 due to the number of imported Flemish manuscripts that flooded the market (Morgan 2013, p. 70). This perhaps suggests that, in this case at least, the patron was concerned with the personalisation of his manuscript and closely involved with its production, rather than simply importing a Book of Hours. The obits of numerous members of the Butler family appear on f.2r-v: James, the fifth Earl of Ormond and first Earl of Wiltshire (†1461); Avice, his wife (†1457); Joan, first wife of James, the fourth Earl (†1452); Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury and sister of the fifth, sixth, and seventh Earls of Ormond (†1473); John, the sixth Earl (†1477); Anne, first wife of the seventh Earl (†1485); Joan Abergavenny, grandmother of the fifth, sixth, and seventh Earls (†1435); and finally Lora, second wife of the seventh Earl († c.1501). The positioning of the obit for Countess Lora at the end of the list but incorporated into the calendar of the Royal manuscript suggests that the Harley manuscript is the earlier of the two. The Royal manuscript also bears a largely erased early sixteenth-century inscription on ff. 3–4 which entreats the reader to pray for the souls of Willelmi Froste and his wife, Juliane, who donated the book to the chapel of the Blessed Mary of Suthwycke [Southwick]. A William Frost was named as a trustee for property belonging to the seventh Earl in a patent livery of the 12th of December 1515 (Letters and Papers 1864, vol II p. 340; Warner and Gilson 1929, vol. I p. 49).4 The list of obits including the seventh Earl’s wives, brothers, sister, mother and grandmother, but none for himself, along with the manuscript passing into the hands of one of his trustees suggests that the manuscript was commissioned for Thomas Butler rather than another member of his family. This is further supported by the original inclusion of an image, suffrage, and obit of his patron St Thomas Becket, later effaced from the manuscript (ff. 29v, 65r, and 79v), and arguably also by the miniature of a male figure kneeling in prayer with his guardian angel at his shoulder at the beginning of prayer to one’s guardian angel on f.66v (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Miniature ahead of the prayer to one’s guardian angel in the Hours of Thomas Butler, f.66v, © British Library Board.

In addition to the Psalter to be chained to his tomb, Butler’s will refers to a further two books in his possession. The first, ‘myn olde sawlter’ which he keeps at Awdere, county Devon he bequeaths to the parish church of Monkeley. The second, a ‘masse boke covered with russett velvett’ he bequeaths to his daughter, Anne, along with a cloak embroidered in gold belonging to his wife (will of Thomas Butler 299–300). Considering the extent of the wealth and cultural capital available to him, these bequests and the surviving manuscripts believed to have been associated with him presumably represent only a portion of his library, which likely would have also included the more fashionable French and Flemish books. His would not have been the only library with multiple copies of the Book of Hours as Eamon Duffy has noted that most gentry households would have had more than one copy (Duffy 2011, p. 58). Butler may also have been the ‘certaine honourable auncient person […] the honnorable Erle of Ormond’ who provided material for the first English biography of Henry V, written in the sixteenth century. In his enthusiasm for manuscripts, Butler was following in a family tradition as his father, the White Earl, had commissioned manuscripts in both English and Irish. In 1420 the White Earl commissioned a translation ‘out of Latin and French into your mother tongue, English’ of The Governaunce of Prynces, a new version of the treatise known as the Secreta Secretorum from Dublin notary James Yonge. He also commissioned an illuminated miscellany in Irish and Latin which is today known as the Book of the White Earl. Butler’s cousin, Edmund MacRichard, likewise commissioned the Book of Pottlerath, an illuminated miscellany in Irish and in doing so incorporated the White Earl’s manuscript into his own. John, the sixth earl, was also a keen scholar and is described by Carte as ‘a perfect master of all the languages of Europe’ (Allmand 1992, pp. 432–33; Carte 1851, vol. I, p. lxxxi; Kerns 2008, p. 1; Kingsford 1911, pp. 3 and xvi–xx; Matthew 1994, p. 119; Ralph 2014; Wylie and Waugh 1929, vol. III pp. 445–48). His grandmother, Joan Beauchamp, was also associated with the Tewkesbury Psalter in which her obit appears, and it seems that the manuscript was bequeathed from mother-in-law to daughter-in-law at least twice (Egbert 1935, pp. 377 and 381).

The ornamentation of Books of Hours dating to the later period generally followed a reasonably fixed scheme of standard images at the standard textual divisions or standard accompanying texts. When groups of miniatures appeared, perhaps as a double opening or as a series of scenes separated by short tracts of text, they were usually positioned as a prefatory cycle or more rarely at the major textual divisions (Morgan 2013, p. 71; Scott 1996, vol. I pp. 38 and 56). Both of Thomas Butler’s Books of Hours, on the other hand, include two series of full page miniatures: the first a series of pictorial cycles which are repeated later in the manuscripts with almost identical compositions but the order reorganised, and the second a series of images dedicated to the Holy Trinity.

2. The Pictorial Cycles

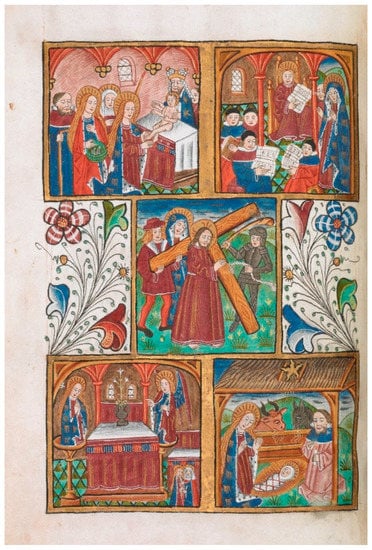

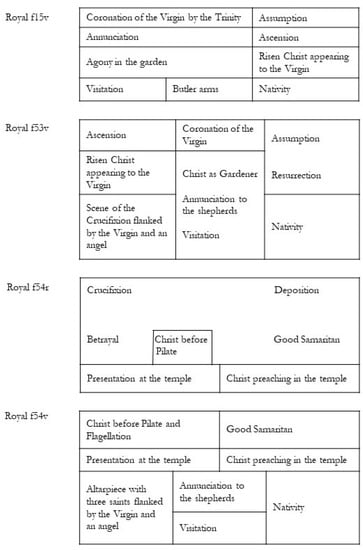

In the Hours of the Earls of Ormond, six of the seven pictorial cycles are grouped together from ff. 55v–58r in front of the Fifteen Oes, a series of devotional prayers commemorating Christ’s Passion, each of which begins with the exclamation ‘O’ (Figure 3 and Figure 4). English in origin, these prayers centred around the seven words Christ uttered on the Cross, His wounds, and the salvation of mankind through His sacrifice, and ultimately became some of the most popular prayers in late medieval England (Duffy [1992] 2005, pp. 249–56; Krug 1999). Each cycle follows the same physical layout in the form of the letter ‘I’ with two scenes in the top register, one in the middle flanked by a floral design, and two on the bottom. The scenes are evenly sized and each is framed with a gold leaf border. Altogether, ten scenes appear in various combinations throughout the cycles: the Annunciation; Nativity; Presentation in the Temple; Christ Preaching in the Temple; Christ Carrying the Cross with the aid of the Good Samaritan; Crucifixion; Deposition; Ascension; Risen Christ Appearing to the Virgin; and Assumption; (see Figure 5 for the layout of each cycle). The group has blank outer leaves, suggesting that they are intended to function as a unit and the same ten scenes are repeated three times each over the course of three consecutive double pages with the order on f.55v reproduced exactly on f.57v and that on f.56r reproduced inverted on f.58r. This slow rotation through ten key scenes, all closely related to the Joys and Sorrows of the Virgin, encourages a ritualistic reading and conscientious reflection on the prayers they preface. The artist of the cycle is described by Kathleen L. Scott as Illustrator B and is identifiable with the so-called ‘Placentius Master’ whose work can be dated to c.1485–1505. This hand appears in numerous and diverse manuscripts, three of which were intended for Henry VII or his immediate family, suggesting that he was held in high regard by his contemporaries (Scott 1996, vol. II pp. 300–1 and 347).

Figure 3.

Pictorial cycle ahead of the Fifteen Oes in the Hours of the Earls of Ormond, f.56r, © British Library Board.

Figure 4.

Pictorial cycle ahead of the Fifteen Oes in the Hours of the Earls of Ormond, f.56v, © British Library Board.

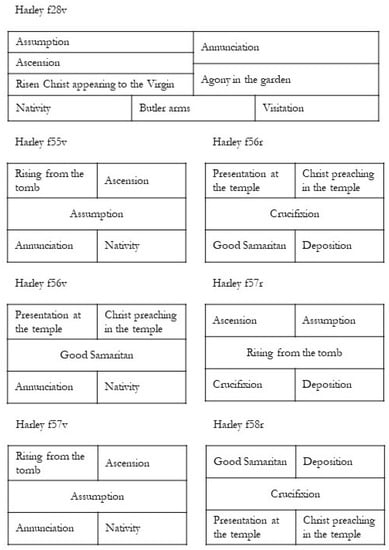

Figure 5.

Layout of the pictorial cycles in the Hours of the Earls of Ormond.

The mythology surrounding the evolution of the Fifteen Oes is unclear; however, it was said that Christ revealed the Oes to a reclusive woman, sometimes said to be St Bridget of Sweden. The woman desired to know how many wounds Christ had suffered during His Passion and He responded that if she were to say fifteen Pater Nosters and fifteen Ave Marias that she would have counted and worshipped each of the wounds. In some more elaborate versions the revelation was made alongside the promise that each recitation would bring forty days of pardon and commutation of sentences to Hell and Purgatory and if they were recited every day for a year, the result would be the release from Purgatory of fifteen family members and the keeping of fifteen living family members in grace. Ultimately, Christ urged let ‘every lettered man and woman read each day these orisons of my bytter passion for his sowlen medicine’ (Louis 1980, pp. 264–68; Duffy [1992] 2005, p. 255; Leroquais 1927, pp. 97–99).

The legends surrounding the Oes, while offering some very enticing rewards, were also concerned with the appropriate reading of the prayers, insisting that each word be afforded due meditation and warned against the dangers of careless reading. Some introductory passages offered analogies with the permanent dulling of precious jewels as a result of careless maintenance by way of explanation. Such warnings and analogies emphasise the importance of reading the prayers rather than their recitation (Krug 1999, p. 111). The material object therefore plays a crucial role in the practice of devotion as the beholder considers the text and interacts with the folia of the manuscript. The pictorial cycles further heighten this interaction. In a world deeply immersed in religious culture and indulgences, images could trigger well known prayers such as the Pater Noster and Ave Maria with or without the presence of the text (Swanson 2007, p. 263). Acting similarly to a rosary, the cycle presents a visual anchor for each of the devotee’s thirty prayers as he carefully enumerates the wounds and contemplates the suffering and sacrifice of Christ for the salvation of mankind. The devotee then arrives at, and meditates on, the Fifteen Oes themselves which relate the excruciating torment endured in vivid terms.

As in the Harley manuscript three of the four pictorial cycles in the Hours of Thomas Butler fall as a group from ff. 53v–54v with blanks immediately before and after (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). The scenes are more numerous with twenty appearing in all and they are as follows: the Virgin and an angel flanking an altar piece depicting three saints; the Virgin and an angel flanking an altar piece of the Crucifixion; Annunciation; Visitation; Nativity; Annunciation to the Shepherds; Presentation in the Temple; Christ Preaching at the Temple; the Agony in the Garden; Betrayal; Christ Before Pilate (and the Flagellation); Christ Carrying the Cross with the aid of the Good Samaritan; Crucifixion; Deposition; Resurrection; Christ as Gardener appearing to Mary Magdalene; Risen Christ appearing to the Virgin; Ascension; Assumption; and the Coronation of the Virgin by the Trinity; (see Figure 9 for the layout of each cycle). The scenes are presented roughly chronologically beginning from the bottom of each cycle and none are repeated on facing pages thus expecting the viewer to move carefully back and forth in order to complete the cycle. Unlike the opening cycle and Harley cycles, the formatting of this grouping is less systematic with a variety of divisions and architectural frames and multiple scenes occupying the same spaces. While considerably more simplistic in execution, the mise-en-page of the cycles are reminiscent of those used in a series of pictorial cycles in fifteenth-century Parisian copies of the Defender of the Immaculate Conception of the Glorious Virgin Mary and the Golden Legend.5 The latter is of note as two of the Golden Legend cycles also include scenes of the Trinity in Glory dressed in a collective cloak, united in their Book of Litanies, and surrounded by seraphim (in the former) and the bottom of a blue mandorla, similar to those in the Holy Trinity miniatures in the Butler manuscripts (see below). Each of the pictorial cycles in this manuscript also bears the Chourses-Coëtivy coat of arms along with the intertwined letters A and K for Antoine de Chourses and Catherine de Coëtivy (Kaplan 2016).

Figure 6.

Pictorial cycle f.53v of the Hours of Thomas Butler, © British Library Board.

Figure 7.

Pictorial cycle f.54r of the Hours of Thomas Butler, © British Library Board.

Figure 8.

Pictorial cycle f.54v of the Hours of Thomas Butler, © British Library Board.

Figure 9.

Layout of the pictorial cycles in the Hours of Thomas Butler.

This grouping in the Royal manuscript is immediately followed by a miniature of the Coronation of the Virgin before the Trinity and the Company of Heaven (Figure 10). Collectively, the images fall between Compline and the Salve Regina and Gaude Virgo hymns on ff. 56–57. By the later Middle Ages, it had become popular to sing the Salve Regina after Compline. Supplicants were also encouraged to sing or speak the words of the hymn before an image of the Virgin Mary as depicted by the devotee with a scroll in a Book of Hours in Trinity College, Cambridge.6 The producer of the Hours of Thomas Butler anticipated the reader to be engaged in a ritualistic act involving sight, touch, thought, and speech: first, a meditation on and uttering of the prayer at Compline introduced by an image of the Entombment;7 second, upon turning the page, a contemplation of the details of the cycle, the scenes of which are again closely related to the Joys and Sorrows of the Virgin;8 third, a contemplation on the Coronation before the Trinity; fourth, singing of the hymns with both a marginal scene of the Virgin and Child next to the words and the preceding miniature providing a visual focal point. The perceived efficacy of prayers, supplications, and gestures said or made in front of images, both in terms of rewards and as a tool to heighten devotional experience, during the late medieval period has been well documented both in England and Europe. In his account of the culture of indulgences at the time, Robert Swanson relates that praying to an image of the arma Christi every day for a year offers 6755 years, six months, and three days’ remission from Purgatory. Similarly, daily recitations of multiple Aves, Paternosters, and Creeds before the Man of Sorrows could exceed 32,000 years’ remission. Thomas Lentes notes the importance of ‘an exact chronology of bodily poses’ to be performed during the Pater Noster and recited seventy-seven times in front of an image of the Mount of Olives as ‘only those who used the right gestures in front of the picture could be sure that the person in it would look at them with merciful eyes and hear their prayer’ (Lentes 2006, p. 362; Swanson 2007, pp. 255, 262).

Figure 10.

The Coronation of the Virgin before the Trinity, the Hours of Thomas Butler, f.55v, © British Library Board.

The opening pictorial cycle in the Royal manuscript occurs on f.15v immediately preceding the Hours of the Virgin (Figure 11). The principal scenes depict the Coronation of the Virgin by the Trinity; Annunciation; and the Agony in the Garden. These are flanked by smaller scenes (from top to bottom): the Assumption; Ascension; Risen Christ appearing to the Virgin; Nativity; and Visitation; with the Butler arms inserted between the bottom two scenes as in the Harley manuscript. The pictorial cycles therefore act as both preface and postface to the Hours of the Virgin. The opening cycle in the Harley manuscript occurs on f.28v, described by Scott as Illustrator G, and incorporates seven narrative scenes (Figure 12). In this case the two principal scenes are of the Annunciation and Agony in the Garden and these are flanked by five smaller scenes (from top to bottom): the Assumption, Ascension, Risen Christ appearing to His mother, Nativity, and Visitation, with the Butler arms inserted between the latter two scenes. Stylistically the Harley cycle on f.28v and Royal cycles are more refined than the group proceeding the Fifteen Oes with delicately rendered facial features, subtle modelling, and thin golden circles and delicate rays for haloes. Scott writes of the Harley manuscript that ‘this glamorous insertion was clearly meant to cope with the inadequacy of the English historiated initial of Matins’ (Scott 1996, vol. II 301). While this may well be true, at least in part, its insertion at this juncture also serves to unite the two series of full-page miniatures in the manuscript: drawing together the recitations demanded of the cycle (and a partial preparatory cycle on f.28r9) with Trinitarian imagery on f.27v in an active preface to Matins complete with the patron’s self-image.

Figure 11.

Opening pictorial cycle, the Hours of Thomas Butler, f.15v, © British Library Board.

Figure 12.

Opening pictorial cycle, the Hours of the Earls of Ormond, f.28v, © British Library Board.

3. The Holy Trinity

The same association between performative act and devotional image in the pictorial cycles is found in the second series of full-page miniatures which depicts the Holy Trinity. Four of the five miniatures inserted into the Hours of the Earls of Ormond depict the Triune God. In somewhat bleak terms, Scott refers to the inserted material as a footnote to a discussion of an English illumination shop in the mid-fifteenth century:

There are two similar though distinct depictions of the Holy Trinity and each is repeated once more a few folia later: pairs A (ff. 6v and 33v) and B (ff. 8v and 27v) (Figure 13 and Figure 14). In both pairs, the figures appear as the Trinity in Glory, the three persons seated side by side in a horizontal arrangement. This type of image, though found less frequently, better preserves the equality of the three persons rather than the co-enthronement type whereby Christ and God the Father appear in line with the dove between them representing the Holy Spirit or the vertical arrangement of the Mercy Seat/Throne of Grace.10 The figures are united under a single crown and framed by the symbols of the Evangelists in the corners. Departing from the equality established in the position, the figures of God the Father and the Holy Spirit are depicted as a rich golden colour, unlike Christ who is much paler with smaller facial features and a narrower frame. Christ is also placed on the left of the group which is relatively atypical of the Trinity in Glory type whereby Christ is usually positioned in the centre (Price-Linnartz 2009, p. 16). The striking radiance differentiates the two pairs. Pair A shows God the Father and the Holy Spirit with strong torsos but no lower bodies alongside Christ with golden rays emanating from their collective waist filling the frame. Pair B on the other hand shows developed lower bodies for all three figures with golden rays bursting dramatically forth from the chest and back of the Trinity with a ring of cherubim and seraphim hovering between them. Scott attributes the illumination of f.27v to Illustrator D and the other three to Illustrator C based on the source and finish of the parchment and the use of rose outlining. Given the iconographic pairs, this would suggest that the two artists were working very closely together and from a common exemplar or donor instruction. This use of rose ink in the Trinity scenes and decorated initials on ff. 7r–12v suggest a French influence and a possible source for the iconography (Scott 1996, vol. II p. 301).the owner apparently wished to make a luxury copy of what would have been, without pictures, merely good production. The inserted miniatures have very much the air of commercialisation about them […] The execution is poor, and the composition is identical between the repeated scenes.(Scott 1968, pp. 172n–73n)

Figure 13.

Holy Trinity, pair A of the Hours of the Earls of Ormond, ff. 6v and 33v, © British Library Board.

Figure 14.

Holy Trinity, pair B of the Hours of the Earls of Ormond, ff. 8v and 27v, © British Library Board.

The Hours of Thomas Butler offers two miniatures dedicated to the Holy Trinity, ff. 9v and 10v (Figure 15 and Figure 16).11 The latter is strikingly similar in every respect with pair B from the Harley manuscript. The compositions and colouring are almost identical with very slight differences in the number of cherubim and seraphim and the colouring of St Matthew’s angel. Such strong similarities in the iconography, compositions, and design choices between the two manuscripts surely suggest a coordinated approach. This prompts the question of whether the refurbishment of the Harley manuscript inspired the commission of the Royal or whether the personalised commission of the Royal manuscript was the catalyst for the insertions in the Harley. While this would be a difficult question to answer without further evidence, Scott’s comment on the ‘glamorous insertion’ remedying the inadequacy of the opening of the Harley Matins may be useful here. Perhaps upon the commissioning of his more lavish manuscript, Butler decided to revitalise an older book with glamorous, functional imagery.

Figure 15.

Holy Trinity, the Hours of Thomas Butler, f.9v, © British Library Board.

Figure 16.

Holy Trinity, the Hours of Thomas Butler, f.10v, © British Library Board.

The composition of the Trinity on Royal f.9v offers a more restrained depiction of the Trinity in Glory type such as that in the Lectionnaire de l’Office de la Sainte-Chapelle de Bourges c.1410, the Chourses-Coëtivy copy of the Golden Legend mentioned earlier, another manuscript belonging to the family, the Coëtivy Hours dating to the mid-fifteenth century or an early sixteenth-century Book of Hours possibly from Lyon.12 The three figures on Royal f.9v are depicted as full length, seated on an invisible throne. As in all the previous images God, the Father and the Holy Spirit are deeper in colour than Christ and in this case, He is bearing the stigmata and Crown of Thorns, and carrying the Cross. The three figures are united through their hands on a common book of litanies but also by their luxuriant scarlet cloak as in contemporary French and Flemish illumination.13 The golden rays are much more muted than in the previous images emanating from behind the throne and outwardly restrained by a blue mandorla which is in turn set within a red background. As in the case of the other five depictions, the symbols of the Evangelists occupy the corners of the frames. While perhaps a little unusual, examples of the Trinity surrounded by a mandorla and the tetramorph are to be found in the fourteenth century in the Hours of Philip the Bold by the Master of the Throne of Mercy and in the miniature with donors in the Pabenham-Clifford Hours,14 recalling alabasters and French and English Gothic ivories and their treatment of the subject.15 Both the Royal miniatures and three of the four in Harley manuscript are inserted preceding or in the middle of prayers dedicated to the Holy Trinity or the three persons of the Trinity.16 As with the pictorial cycles, the images provide a visual focus for the supplicant’s devotions.

Despite the somewhat unflattering description of the quality of execution, Scott nevertheless regards the miniatures as significant, describing them as ‘unique iconographically in English illustration and worthy of note because of the Gospel symbols, the three full-length nude Trinity figures and the massive radiance as substance of the Trinity with three heads’ (Scott 1996, vol. II 301). Such a strong focus on the rays raises a question about the inspiration for or origin of the imagery but also poses an interesting solution to a theological and iconographical problem. Reducing the mystery of the Trinity to visible human form is a theological hurdle and thus limitations are imposed on all figural representation. While scripture provides physical manifestations for the second and third persons in the flesh, in fire, and in the form of the dove, God the Father remains invisible (John 1:18). Given the Trinity ‘is invisible in such a way that it is not seen even by the mind’, Augustine of Hippo forbade all attempts to picture the Trinity, symbolic or anthropomorphic. Likewise, Pseudo-Dionysius places the concept beyond human imagination opening his De mystica theologia: ‘Trinity, higher than any being, any divinity, any goodness!’ (Augustine 1990, p. 136; McGinn 2006, p. 186; Price-Linnartz 2009, p. 3; Pseudo-Dionysius 1991, vol. II 141; Rorem 2015, p. 9).

Obscuring the physical forms with the radiance enables the artist to surmount this theological obstacle and focus on the collective essence of the Trinity. The dazzling radiance at once presents the character of the Holy Spirit in the form of fiery tongues while simultaneously presenting the three persons as equal and co-eternal: ‘together not three lights, but one light […] one essence’. Both Augustine and Gregory of Nazianzus describe the intensity of the light emanating from the Holy Trinity, Augustine refers frequently to a ‘so transcendent light’, a ‘blaze of light’ and an ‘ineffable light [that] beat back our gaze’ and Gregory to an ‘ineffable’ light that ‘irradiates the whole universe’. The radiance also however allows the artist to explore the more visionary, emotional, and personal aspects of Trinitarian writings, for example Gregory relates, ‘[n]o sooner do I conceive of the One than I am illumined by the Splendour of the Three; no sooner do I distinguish Them than I am carried back to the One. […] When I contemplate the Three together, I see but one torch, and cannot divide or measure out the Undivided Light’ (Augustine 1886, pp. 19, 86, 109, 204; Gregory 1894, pp. 361, 375).

The drama and intensity of the Butler iconography is perhaps however more in keeping with the passionate language of the twelfth- and thirteenth-century mystics such as Hildegard of Bingen who describes how the ‘bright light [representing God the Father] bathed the whole of the glowing fire [representing the Holy Spirit], and the glowing fire bathed the bright light; and the bright light and the glowing fire poured over the whole human image [Christ], so that the three were one light in one power of potential.’ Gertrude of Helfa exclaims ‘O ardent fire […] O consuming fire […] O burning furnace’ and Mechthild of Magdeburg describes the light of the Trinity as ‘God let[ting] his fiery spirit shine forth unceasingly from his Holy Trinity into this loving soul, just like a bright sunbeam shining forth from the hot sun lights up a golden shield’ (Gertrude 1992, p. 105; Hildegard 1990, p. 206; Mechthild 1998, p. 179; Ray 2011). These fervent descriptions stimulate the reader’s emotional, rather than rational, response to the burning mystery of the Holy Trinity. Similarly, in the Books of Hours the theatrical bursting forth of the radiance from the torsos of the three persons commands the reader’s attention, elicits their personal and emotional responses, and inspires their devotional gaze.

Contemporary religious theatrical productions similarly utilised light, fire, and radiance to captivate their audiences and convey messages of divinity. Actors playing the role of God were traditionally masked or painted in gold to mark them out as divine both in England and abroad. Play expenses in York for example included gilded masks and yellow wigs for the Doomsday pageant and in Chester and Coventry the expenses list the gilding of players’ faces (Muir 1997, pp. 33–35; Stevens 2013, p. 24; Twycross and Carpenter 2002, p. 220). This gilding ties in well with the golden depictions of God the Father and the Holy Spirit in the Books of Hours and with the golden face of God in stained glass of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a practice described by Émile Mâle as ‘a relic of the religious theatre’. Pyrotechnics and other lighting devices were also involved in the staging of plays. The Chester Pentecost, for example, directs God to send forth the Holy Spirit in the form of fire, ‘in spetie ignis’, and angels cast flames on the apostles while singing the antiphon Accipite Spiritum Sanctum [Receive the Holy Spirit]. Medieval accounts seem to support the idea that the apostles were showered with real fire in these scenes rather than ribbons or props. In her discussion of the staging of the York Transfiguration, Andrea Ria Stevens proposes that a metallic reflector could be used to focus and direct either sunlight or candlelight (likely augmenting an already gilded mask or effect of golden face paint) in order to create the illusion that the light of the Transfiguration was coming from within the figure of Christ himself. Such directions had been provided for the Revello [Piedmont] production of the play. The actor could also rapidly change his garments to reveal a snow-white robe to further the dramatic change (Lumiansky and Mills [1974] 1986, play 21, line 238; Mâle 1987, pp. 108–9; Muir 1997, p. 35; Stevens 2013, pp. 30–31; Twycross 2008, p. 38). This bouncing of light off a reflective plate on an actor’s chest could certainly create, or at least inspire, a similarly dazzling effect to that of Butler’s Trinitarian imagery. The iconography of the Books of Hours acts therefore as a catalyst to prayer and demonstrates both a rather creative and somewhat eclectic solution to the representation of a theologically and intellectually difficult subject with references to a variety of sources and styles in different media and perhaps some influence also from the performing arts.

Furthermore, though not a gruesome depiction of suffering—as in for example the Trinity of the Broken Body type which shows the dying body of Christ in an amalgamation of the Christ of Sorrows or Corpus Christi and Trinitarian imagery—the depiction of the wounds emphasises Christ’s sacrifice. Such iconography is again designed to elicit an emotional response from the viewer, to move the viewer to penance and contemplation both of Christ’s sacrifice for the salvation of mankind as the result of a decision by all three persons and of the fate of the viewer’s own mortal soul. François Bœsflug associates the rise in funerary Trinitarian imagery across Europe from the second half of the fourteenth century with the intercessory power of the Holy Trinity. Devotees at their hour of greatest need seek comfort directly from the three persons and pity and understanding from a suffering Christ. This instrumental approach is also witnessed in the pleas for mercy in the Fifteen Oes, emphasising the bond between Christ’s suffering and His infinite love of humanity and the promise of forgiveness (Bœsflug 2001; Duffy [1992] 2005, p. 250; Krug 1999, p. 108).17

Harley f.27v also bears the traces of pilgrim badges, pinpricks forming two circles where a badge(s) were previously pinned to the folio. Certain members of the Ormond family are known to have undertaken or at least contemplated undertaking pilgrimages. Butler’s father, the White Earl for example, was granted dispensation in 1431 for a journey to Rome. Likewise, his brother John, the sixth earl, died on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1477–1478 in what Thomas Carte describes as ‘a fit of devotion’ (Calendar of entries in the Papal Registers 1909 vol. VIII 278; Carte 1851, vol. I lxxxi). This sort of customisation of a Book of Hours through the insertion of a pilgrim badge was popular in the late Middle Ages, examples of which may be found on manuscripts originating from and belonging to families and religious communities in England, France, and Flanders such as a late-fifteenth-/early-sixteenth-century manuscript belonging to members of a family in Bordeaux or the elaborately adorned d’Oiselet Hours produced in Bruges and belonging to Claude de la Chambre of Franche-Comté.18 As Virginia Reinburg has demonstrated, pilgrim badges offered the pilgrim a tangible, tactile memory of their experience.

By incorporating his pilgrim badges into the Book of Hours, Butler had a sensory aid to memory to help him recall his experience. Just as his Psalter with his name chained to his tomb bearing his epitaph encouraged the reader to bear him in his prayers, the pilgrim badges encouraged a multi-sensory devotional experience combining his personal esoteric devotional interests with vivid imagery of an almost mystical nature and the tactile souvenir of a physical devotional experience.More than a mere memento of a trip, such souvenirs reminded returned pilgrims of their experience in a concrete way. Just as touching a relic or image—even through the mediation of tomb or shrine—conveyed the presence and power of the saint to pilgrims, so the souvenir conveyed the memory of the pilgrim’s experience at the shrine. This was a culture in which memory was an art. Wearing, seeing, and handling objects provided a material memoir of the pilgrimage.(Reinburg 2012, p. 81)

Devotional imagery in English and French Books of Hours typically takes the form of the Five Wounds, Man of Sorrows, Mass of St. Gregory, arma Christi, and the Veronica, and the associated indulgences often offered magnificent rewards. These same motifs were also typical of devotional imagery in Ireland from this period (Connaughton 2012; Duffy 2011, pp. 15–16; Duffy [1992] 2005; Lewis 1993; Reinburg 2012, pp. 117–23). The tomb of Butler’s distant cousin and heir, Piers, and his wife, Margaret, in St. Canice’s Cathedral displays the arma Christi for example, as does a tomb of an unknown Butler knight at Gowran. Indeed, Salvador Ryan, in his assessment of the motif in late medieval and early modern Ireland, notes that in the sixteenth century the arma Christi came to replace depictions of the saints on tombs. Furthermore, Ryan notes that this devotion to the arma Christi was rather localised in Kilkenny, the heart of Butler influence (Ryan 2014, pp. 253–55). Thomas Butler does not appear to have shared in this particular interest in the arma Christi as it only appears in the older portion of the Harley manuscript introducing Psalm 21, f.105r; whereas the equivalent historiated initial in the Royal manuscript depicts a Mass of St Gregory, f.126r.

The devotional focus on the Holy Trinity seems to suggest therefore a personal choice on behalf of the patron. This choice may also reflect a familial devotional preference as in her investigation of images of the Holy Trinity from the Middle Ages and Early Modern period in Ireland, Helen M. Roe noted a particular centrality in their locations or points of origin: ‘and of these it is to be remarked that no fewer than eight are or were associated with sites in Ossory, either in Kilkenny city or in the area of the modern county’ (Roe 1979, p. 101). Taking into consideration only those from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Roe lists five examples from Kilkenny and all of them take the form of the Throne of Grace: a stone altar piece at Callan from c.1535 to 1541;19 two stone cloister panels from the second half of the fifteenth century, one at each of Inistioge Priory and Jerpoint Abbey; an alabaster statue group from the first quarter of the fifteenth century at Black Abbey; and a now lost or destroyed stone panel thought to date to the late fifteenth century from St. Patrick’s burial ground, known through early nineteenth-century drawings by George Millar. In addition, she lists one example from Fethard, Co. Tipperary, of a wooden statue group of the Throne of Grace from c.1490 to 1520, of which only God the Father survives (Roe 1979, pp. 110, 112). As before with the arma Christi, this concentration corresponds to Butler lands, furthermore Callan was founded by Edmund MacRichard and the renovations of Jerpoint Abbey were patronised by the White Earl, Butler’s cousin and father.20

4. At the Crossroads

Butler’s private life and political career placed him at the intersection of a variety of cultural and social spheres. Prominently engaged in English public life and comfortable in the courtly circles of England and France, Butler also maintained links with his family and sphere of magnates in Ireland as touched on above. Butler’s Books of Hours illustrate ties with his Anglo-Irish heritage and Gaelic-Irish culture as both manuscripts observe the feasts of St Brigit of Kildare and St Patrick in their calendars (Harley ff. 21v and 22r and Royal ff. 3v and 4r) and the Hours of the Virgin in the Royal manuscript also contains a memorial to St Patrick during Lauds f.16r and in the litany on f.80r.

Another item listed in Butler’s will, a small ivory horn given to him by his father, further demonstrates his position at the juncture of Anglo-Irish and English culture:

It is clear from the language used in the will that the horn was of significance to the Ormond household. In fact, Carte claims that the horn bequeathed was held to be the one from which Thomas Becket himself drank ‘and was kept very religiously in the family till this time’ and Butler proceeds to name a further heir to the horn should Thomas Boleyn die without issue (Carte 1851, vol. I p. lxxxiv). The horn, not least due to its alleged associations with Becket, was a mark of honour for the Butler family, and this was also true of other families in both England and Ireland. John Cherry has argued that horns in Britain held a symbolic importance in terms of ownership and transference of land. The Pusey Horn for example was furnished in the fifteenth century with a band with an inscription recording that: ‘I kynge knowde [Cnut] gave Wyllyam Pecote [Pusey] thys horne to holde by thy land’ (Cherry 1989, pp. 112–13). A reference to the so-called Kavanagh ‘Charter’ Horn in the Civil Survey of Co. Carlow 1654–1956 states that the Kavanaghs were ‘descended from the stock of the kings of Leinster, had a great seate and a vessel or cup to drink out of called Corne-cam-mor’ suggesting a similar function as symbol of office and tenure in an Irish context. At some stage during the fifteenth century Art MacMurrough Kavanagh or his immediate descendants commissioned the construction or refurbishment of the ‘Kavanagh ‘Charter’ Horn’, an imitation buffalo horn goblet carved from an elephant’s tusk. The goblet was intended for use in royal inauguration ceremonies, recalling an old Irish tradition that only those who drank from the buffalo horn of Cualu could succeed to the kingship of Leinster (Byrne [1973] 2001, pp. 152–53; Ó Floinn 1994, pp. 270, 274; Simington 1961, vol. X misc. 9; Simms 2010, p. 7). The inventory of plate belonging to the Fitzgeralds, Earls of Kildare, dated 1518, also included ‘a grete rede horne, bownd & gylt’ (MacNiocaill 1992, p. 303). Thus, in addition to its contractual symbolism, the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century concern for the horn demonstrated by the Butlers, Kavanaghs and Fitzgeralds suggests a performative interest in reinvigorating the heroic past, lengthy lineage and traditions. As Katharine Simms writes of the commissioning of the Kavanagh ‘Charter’ Horn, it presents an ‘[attempt] not merely to preserve tradition, but to re-enact the past’ (Simms 2010, p. 8). As with the Psalter chained to his tomb in St Thomas of Acre, this private familial object of the horn also assumed an important public role demonstrating legacy and lineage.Item wher my lorde my ffather whose soule God assoyle left and delivered unto me a lytle whyte horne of ivory garnysshed at bothe thendes with golde and a corse thereunto of whyte sylke barred with barres of gold and a tyret of golde thereuppon the wych was myn auncetours at first tyme they were called to honor and hath sythen continually remained in the same blode for wych cause my said lord and ffather commaunded me uppon his blessing that I shuld doe my devoir to cause it to contynew styll in my blode [...] I woll that myn executours delyver unto Sir Thomas Boleyn knyght sonne and heire apparaunt of my said doughter […].(will of Thomas Butler 301)

The Hours of Thomas Butler and the insertions into the Hours of the Earls of Ormond offer a personal reflection of their owner. A prominent figure in English and French public life with an Irish heritage, the products of his patronage were influenced by the various facets of his world. Marked by English prayers, French designs, Irish saints, borrowed folia, and some individual artistic flair and creativity these manuscripts present a combination of standard, personal, and familial devotions. A pious and devoted reader, Butler’s Books of Hours also show him to be an individual concerned with tangible, measurable results, combining imagery, prayer and repetition in an active performance of piety with a particular interest in devotions to the Passion and Holy Trinity. This active participation and concern for results was also true of the more public aspects of his commemoration and the performance of lineage and tradition demonstrated in the bequest of the horn. As with the Psalter chained to his tomb and the ivory horn held dearly by generations of his family, Thomas Butler’s Books of Hours were performative objects, family records, ‘archives of prayer’ (Reinburg 2012), and material aids to devotion.

Funding

Travel for this research was funded in part by the NYU Global Faculty Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Augustine of Hippo. De Trinitate. Translated by Arthur West Haddan and Rev. William G.T. Shedd. New York: Philip Schaff, 1886.Augustine of Hippo. Letter 120, Letters: The Works of Saint Augustine, A Translation for the Twenty First Century. Edition by John E. Rotelle. Brooklyn: New City Press, 1990.Bourges, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 35, f1v, Lectionnaire de l’Office de la Sainte-Chapelle de Bourges.Calendar of entries in the Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland: Papal Letters. Twemlow, J.A., ed. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1909.Calendar of Ormond Deeds, 1172–1603. Curtis, Edmund, ed. Dublin: The Stationery Office, 1935.Calendar of Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry VI, 1429–1436. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1907.Calendar of Wills Proved and Enrolled in the Court of Husting, London. Sharpe, R.R., ed. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1890.California, St John’s Seminary, Edward L. Doheny Memorial Library MS 3970, Psalter.Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS 242, Pabenham-Clifford Hours.Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS 3-1954, Hours of Philip the Bold.Cambridge, Trinity College MS B.11.7, Book of Hours.Dublin, Chester Beatty Library MS W 82, Coëtivy Hours.Gertrude of Helfa. The Herald of Divine Love. Translated by Margaret Winkworth. New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1992.Gregory of Nazianzus. Oration 40, ‘Select Orations of Saint Gregory Nazianzen, Sometime Archbishop of Constantinople’, Brown, Charles Gordon and James Edward Swallow (trans.), in Schaff, Philip (ed.), A Select Library of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, volume VII: Cyril of Jerusalem and Gregory Nazianzen (New York, 1894: The Christian Literature Company).Hildegard of Bingen. Scivias. Translated by Columba Hart and Jane Bishop. New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1990.Irish Monastic and Episcopal Deeds AD 1200-1600. White, Newport B., ed. Dublin: The Stationery Office, 1936.Kew, National Archives PROB 11/18/184, Will of Thomas Butler, seventh Earl of Ormond, dated 31st of July 1515, (dated in the National Archives’ catalogue as 25th of August 1515 as the date on which it was proved) transcription from Beresford see below.Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic in the Reign of Henry VIII. Brewer, J.S., ed. London: Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1864.London, British Library Egerton MS 3883, Book of Hours.London, British Library Harley MS 2887, Hours of the Earls of Ormond.London, British Library Harley MS 3756, Kildare Rental.London, British Library Royal MS 2 B XV, Hours of Thomas Butler.Mechthild of Magdeburg. The Flowing Light of the Godhead. Translated by Frank Tobin, Frank. New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1998.New York, Morgan Library MS 287, Book of Hours.New York, Morgan Library MS G 9, Book of Hours.New York, Morgan Library MS M 8, Breviary.Nottingham, University Library MS 250, Wollaton Antiphonal.Oxford, Bodleian Library Douce MS 51, Book of Hours.Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS Fr. 244, Golden Legend.Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS Fr. 989, Defender of the Immaculate Conception of the Glorious Virgin Mary.Pennsylvania, Lehigh University, Lehigh Codex 18, Book of Hours.Princeton, University Library Garrett MS. 34, Tewkesbury Psalter.Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita. Corpus Dionysiacum. Heil, Günter, and Adolf M. Ritter, eds. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1991.Rotuli Parliamentorum ut et Petitiones, et Placita in Parliamento. London, 1767–1777.The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek MS 77 L 60, d’Oiselet Hours.Secondary Sources

- Allmand, Christopher. 1992. Henry V. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Beresford, David. 1999. The Butlers in England and Ireland, 1405–1515. Ph.D. dissertation, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Bœsflug, François. 2001. La Trinité à l’heure de la mort: sur les motifs trinitaires en context funéraires à la fin du Moyen Âge (m. XIVe-déb. XVIe siècle). Cahiers de Recherches Médiévales et Humanistes 8: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Eric St. J. 1956. Irish Possessions of St. Thomas of Acre. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 58: 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna, Denis. 1998. Témoins de devotions dans les livres d’heures à la fin du moyen âge. Revue Mabillon New Series 9: 127–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Francis John. 2001. Irish Kings and High-Kings. Dublin: Four Courts Press. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan, William. 1905. The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker. [Google Scholar]

- Carte, Thomas. 1851. The Life of the Duke of Ormond. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, John. 1989. Symbolism and Survival: Medieval Horns of Tenure. Antiquaries Journal 29: 111–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cokayne, George Edward. 1945. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom: Extant, Extinct and Dormant. London: The St Catherine Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connaughton, Jill. 2012. Art and Devotions to the Passion of Christ in Ireland 1450–1650. Ph.D. dissertation, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Anne. 2002. Letters of the Queens of England. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. First published 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, Eamon. 2005. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England c.1400–c.1580. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, Eamon. 2011. Marking the Hours: English People and their Prayers 1240–1570. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert, Donald Drew. 1935. The ‘Tewkesbury’ Psalter. Speculum 10: 376–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortescue, Sir John. 1869. The Works of Sir John Fortescue, Knight. London: Chiswick Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Campbell, Megan H. 2011. Pilgrimage through the Pages: Pilgrims’ Badges in Late Medieval Devotional Manuscripts. In Push Me, Pull You: Imaginative and Emotional Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art. Edited by Sarah Blick and Laura D. Gelfand. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 227–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gaborit-Chopin, Danielle. 2003. Ivoires Médiévaux: Ve-XVe Siècle. Paris: Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Vanessa. 1992. Burial choice and burial location in later medieval London. In Death in Towns: Urban Responses to the Dying and the Dead, 100-1600. Edited by Steve Bassett. Leicester: University Press, pp. 119–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hindman, Sandra, and James H. Marrow, eds. 2013. Books of Hours Reconsidered. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. C. 2016. La Légende dorée, Paris, BnF, fr.244-245 (1480–1485): Un manuscript conçu pour Catherine de Coëtivy. In Les Femmes, la Culture et les Arts en Europe entre Moyen Âge et Renaissance, Women, Art and Culture in Medieval and Early Renaissance Europe. Edited by Cynthia J. Brown and Anne-Marie Legaré. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Keene, Derek, and Vanessa Harding. 1987. Historical Gazetteer of London Before the Great Fire Cheapside; Parishes of All Hallows Honey Lane, St Martin Pomary, St Mary Le Bow, St Mary Colechurch and St Pancras Soper Lane. London: Centre for Metropolitan History. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Kathleen E. 2014. Reintroducing the English Book of Hours, or English Primers. Speculum 89: 693–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, Lin, ed. 2008. The Secret of Secrets (Secreta Secretorum): A Modern Translation, with Introduction of the Governance of Princes. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge, ed. 1911. The First English Life of Henry V Written in 1513 by an Anonymous Author Known Commonly as the Translator of Livius. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, Rebecca. 1999. The Fifteen Oes. In Cultures of Piety: Medieval English Devotional Literature in Translation. Edited by Anne Clark Bartlett and Thomas H. Bestul. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 107–17, 212–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lentes, Thomas. 2006. ‘As far as the eye can see…’: Rituals of Gazing in the Late Middle Ages. In The Mind’s Eye: Art and Theological Arguments in the Middle Ages. Edited by Jeffrey E. Hamburger and Anne-Marie Bouché. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 360–73. [Google Scholar]

- Leroquais, Abbé V. 1927. Les Livres d’Heures: Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque Nationale. Paris: Macon, Protat Frères. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Flora. 1993. From image to Illustration: The Place of Devotional Images in the Book of Hours. In Iconographie Médiévale: Image, Texte, Contexte. Edited by Gaston Duchet-Suchaux. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lodge, John. 1754. The Peerage of Ireland or a Genealogical History of the Present Nobility of That Kingdom with Their Paternal Coat of Arms. London: William Johnston. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, Cameron. 1980. The Commonplace Book of Robert Reynes of Acle: An Edition of Tanner MS 407. New York: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Lowden, John. 2013. Medieval and Later Ivories in the Courtauld Gallery, Complete Catalogue. London: Paul Holberton. [Google Scholar]

- Lumiansky, Robert Mayer, and David Mills, eds. 1986. The Chester Mystery Cycle. Oxford: University Press. First published 1974. [Google Scholar]

- MacHarg, John Brainerd. 1917. Visual Representations of the Trinity: An Historical Survey. New York: Arthur H. Crist. [Google Scholar]

- MacNiocaill, Gearóid, ed. 1992. Crown Surveys of Lands 1540–41 with the Kildare Rental Begun in 1518. Dublin: The Irish Manuscripts Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Mâle, Émile. 1987. Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages—A Study of Medieval Iconography and its Sources. Princeton: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew, E. A. E. 1994. The Governing of the Lancastrian Lordship of Ireland in the Time of James Butler Fourth Earl of Ormond. Ph.D. dissertation, Durham University, Durham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- McGinn, Bernard. 2006. Theologians as Trinitarian Iconographers. In The Mind’s Eye: Art and Theological Arguments in the Middle Ages. Edited by Jeffrey E. Hamburger and Anne-Marie Bouché. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 186–207. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Nigel. 2013. English Books of Hours c.1240–c.1480. In Books of Hours Reconsidered. Edited by Sandra Hindman and James H. Marrow. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 66–95. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, Lynette. 1997. Playing God in Medieval Europe. In The Stage as Mirror: Civic Theatre in Late Medieval Europe. Edited by Alan E. Knight. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Floinn, Raghnall. 1994. The Kavanagh ‘Charter’ Horn. In Irish Antiquity: Essays Presented to Professor M.J. O’Kelly. Edited by Donnchadh Ó Corráin. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 268–78. [Google Scholar]

- Price-Linnartz, Jacki. 2009. Seeing the Triune God: Trinitarian Theology in Visual Art. Master of Theology dissertation, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph, Karen. 2014. Medieval Antiquarianism: The Butlers and Artistic Patronage in Fifteenth-Century Ireland. Eolas: The Journal for the American Society of Irish Medieval Studies 7: 2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, Richard H. 1993. The Golden Age of Ivory: Gothic Carvings in North American Collections. New York: Hudson Hills. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Donna E. 2011. ‘There is a Threeness about You’: Trinitarian Images of God, Self, and Community among Medieval Women Visionaries. Ph.D. dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Reinburg, Virginia. 2012. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c.1400–1600. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, Helen M. 1979. Illustrations of the Holy Trinity in Ireland: 13th to 17th Centuries. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 109: 101–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rorem, Paul. 2015. The Dionysian Mystical Theology. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Salvador. 2014. The Arma Christi in medieval and early modern Ireland. In The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture. Edited by Lisa H. Cooper and Andrea Denny-Brown. Surrey: Ashgate, pp. 243–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sand, Alexa. 2014. Vision, Devotion and Self-Representation in Late Medieval Art. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Kathleen L. 1968. A Mid-Fifteenth-Century English Illuminating Shop and its Customers. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 31: 170–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Kathleen L. 1996. Later Gothic Manuscripts 1390–1490. London: Harvey Miller Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Simington, Robert C., ed. 1961. The Civil Survey 1654–1656. Dublin: Stationery Office for the Irish Manuscripts Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Simms, Katharine. 2010. The Barefoot Kings: Literary Image and Reality in Later Medieval Ireland. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 30: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Steer, Christian Oliver. 2013. Burial and Commemoration in Medieval London, c.1140–1540. Ph.D. dissertation, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, Andrea Rea. 2013. Inventions of the Skin: The Painted Body in Early English Drama. Edinburgh: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stow, John. 1908. A Survey of London. Oxford: Clarendon. First published 1603. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Anne. 2008. The Hospital of St Thomas of Acre of London: The Search for Patronage, Liturgical Improvement, and a School, under Master John Neel. 1420–63. In The Late Medieval English College and Its Context. Edited by Clive Burgess and Martin Heale. York: Medieval Press, pp. 199–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Anne F., and Peter William Hammond, eds. 1983. The Coronation of Richard III: The Extant Documents. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, Robert Norman. 2007. Indulgences in Late Medieval England: Passports to Paradise? Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Twycross, Meg. 2008. The Theatricality of Medieval English Plays. In The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Theatre. Edited by Richard Beadle and Alan J. Fletcher. Cambridge: University Press, pp. 26–74. [Google Scholar]

- Twycross, Meg, and Sarah Carpenter. 2002. Masks and Masking in Medieval and Early Tudor England. Ashgate: Aldershot. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Sir George F., and Julius P. Gilson. 1929. Catalogue of the Western Manuscripts in the Old Royal and King’s Collections in the British Museum. London: Longmans, Green & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Watney, John. 1906. Some Account of the Hospital of St Thomas of Acon, in the Cheap, London, and of the Plate of the Mercer’s Company, 2nd ed. London: Blades, East & Blades. [Google Scholar]

- Weever, John. 1767. Ancient Funeral Monuments of Great Britain, Ireland, and the Islands Adjacent. London: W. Tooke. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Paul. 1982. An Introduction to Medieval Ivory Carvings. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Paul, and Glyn Davies. 2014. Medieval Ivory Carvings 1200–1550. London: Victoria and Albert Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, James Hamilton, and William Templeton Waugh. 1929. The Reign of Henry V. Cambridge: University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Thomas Butler and Anne Hankeford were married sometime before the 18 July 1445 when Butler sued for seisin of her lands, see Calendar of Patent Rolls, 261. |

| 2 | ‘Hic iacet Thomas filius Jacobi, comitis Ormundie, ac fratris Jacobi, comitis Wilts & Ormundie, qui quidem Thomas obijt fecundo die 1515, & anno regni regis Henrici octaui 37.’ |

| 3 | ‘Domine labia mea aperies’ on Harley f.29r and Royal f.16r. |

| 4 | ‘Orate pro animabus Willelmi Froste et Juliane uxoris eius, qui hunc librum dederunt remanere imperpetuum ad orandum beate Marie in ista capella de Suthwycke’, ff. 3-4, transcription from (Warner and Gilson 1929, vol. I p. 49). |

| 5 | Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS Fr. 989, and Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS Fr. 244 respectively. |

| 6 | Cambridge, Trinity College MS B.11.7. |

| 7 | In the Royal manuscript the hours are introduced in a relatively, though perhaps not wholly, typical manner with scenes from the Passion: the Visitation introduces Matins (f21v) though ordinarily this would offer a scene of the Annunciation; the Betrayal appears at the Lauds division (31v); Christ Before Pilate at Prime (though this is less frequent than the Betrayal at this division) (35v); Terce depicts Christ Carrying the Cross (though typically Christ Before Pilate or the Flagellation appear) (38v); Nailing to the Cross at Sext (Scott notes only two copies) (41v); Crucifixion at None (44v); Deposition at Vespers (49r); Entombment at Compline (52r); for a discussion see Scott 1996, vol. I p. 56. |

| 8 | The Seven Joys of the Blessed Virgin Mary appear on f.63v introduced by a historiated initial G with a scene of the Virgin seated before the Trinity. |

| 9 | Two partial preparatory scenes depict the Annunciation above the Agony in the Garden in a similar approach to the finished cycle on the verso. |

| 10 | For English examples of the Trinity in Glory type, see: the Wollaton Antiphonal, Nottingham, University Library MS 250, f246v dating to c.1430; a Book of Hours, New York, Morgan Library MS G 9, dating to c.1440–1450; and Camarillo, California, St John’s Seminary, Edward L. Doheny Memorial Library MS 3970 f88r dating to c.1460–1470; for a discussion of the types of Trinitarian imagery see (MacHarg 1917). |

| 11 | Trinitarian imagery is continued throughout the manuscript with a further miniature depicting the Virgin before the Holy Trinity and surrounded by the company of heaven on f.55v. The pictorial cycle on f.15v incorporates a scene of the Coronation of the Virgin by the Trinity and three initials are historiated with scenes of the Trinity: a Crucifixion type on f.12r (comparatively rare), a Throne of Grace whereby the dove is perched on the bar of the Cross on f.62r, and a Virgin before the Trinity on f.63v which is very similar to the miniature on f.9v but without the attributes. |

| 12 | Bourges, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 35; Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS Fr. 244; Dublin, Chester Beatty Library MS W 82; and Pennsylvania, Lehigh University, Lehigh Codex 18 respectively. |

| 13 | See for example New York, Morgan Library MS 287 f134r dating to c.1445 and New York, Morgan Library MS M 8 f136v dating to c.1511. |

| 14 | Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS 3-1954 and Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum MS 242 respectively. |

| 15 | See for example: Toronto, Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario 107363, an English diptych fragment; Washington, D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum 1929.8.240.12, an English diptych; London, Courtauld Gallery O.1966.GP.2, a French diptych fragment; London, Courtauld Gallery 305, a cast of a lost French diptych, all dating to the first half of the fourteenth century. For a discussion of ivory carving see: (Gaborit-Chopin 2003; Lowden 2013; Randall 1993; Williamson 1982; Williamson and Davies 2014). |

| 16 | The miniature on Royal f.33v appears in the middle of the Te Deum hymn. |

| 17 | A further prayer with indulgences equalling the number of Christ’s wounds granted by Pope Benedict XII, ‘Precor te piissime Ihesu Christi’ appears on f.60r of the Royal manuscript. |

| 18 | See for example London, British Library Egerton MS 3883, f142v, a fifteenth-century manuscript with Netherlandish and English origins; Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Douce 51, ff. 45v, 57v, 58v, 59r, 74r; and d’Oiselet Hours, The Hague, Koninklijke Bibliotheek MS 77 L 60, f98r; see (Bruna 1998, pp. 127–61; Foster-Campbell 2011, vol. I pp. 234–37). |

| 19 | Originally from the Church of the Blessed St. Mary at Callan. |

| 20 | Edmund MacRichard Butler undertook to found the Augustinian Friary at Callan, Co. Kilkenny in 1461, although the actual establishment of the friary fell to his son James after his death in 1464, see: Calendar of entries in the Papal Registers 1909, vol. IX p. 248, vol. XII p. 25; (Carrigan 1905, vol. III p. 311); Irish Monastic and Episcopal Deeds, 1936, nos. 6 8, 15, 18. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).