1. Introduction

African religion is ambiguous and quite contradictory. It can be favorably associated with agreeable human qualities, such as ethnicity, morality, and spirituality, or negatively with superstition, rejection of scientific knowledge and human progress, in general (

Oestigaard 2014). Religion manifests in many shapes and holds great power over minds and bodies, societies, and cultures, playing an essential role in many cultures. In African culture, one is born into the faith of your family cult, and one’s culture is, in essence, also one’s religion permeating a person’s entire life to inform the material, moral, and spiritual aspects (

Mbiti 1975). Religion, broadly conceived, is intertwined in socio-economic development (

Sundqvist 2017). It plays a role of inspiration for political change and agency for people’s health (

Beckford 2017). Some African communities connect religion, especially under the concept of health and healing, with their daily life. Cosmology is structured around the cultural role of rainmaking, which was the Chief’s responsibility. Rain here is perceived as life-giving and a remedy for the ‘maladies’ of the land (

Oestigaard 2018).

As a fundamental aspect of culture, religion was used to organize resistance and instigate the fight against injustice. More specifically, this was the case during the Majimaji resistance where the

Bokero and

Kolelo cults were employed in an attempt to overcome the fear of German armory. A ritualist by the name of Kinjekitile Ngwale prophesied that by using a water concoction (

Maji) to bath, spray, or rub on the body, people would be immunized against the German’s weapons. Historians have debated over which religion was specifically used—Christianity, Islam, or local cults. While Gilbert Gwassa was convinced that local religion was solemnly sought and that the Majimaji was purely indigene (

Gwassa 1973), Thaddeus Sunseri provides cases where Abrahamic sources might have been used, either in the actual organization of the war or in the colonial representation of different episodes of the war, to bring the resistance into the currently recognized form (

Sunseri 1999). Archaeological and ethnographic researches conducted under this study concluded that religion was intertwined in the Majimaji phenomenon and, long after the occurrence of the war for the purposes of commemoration, employed in fighting injustice and has been perpetuated as the southern Tanzania cult. Although the Majimaji movement started purely as an earthly organized resistance, African religion is never solitary. It is a matter of the African belief system that healing is sought from all available powers until the maladies/ailments are removed from the individual or society (

Larsen 2008). Henceforth, cults, crescents, and crosses represent a ‘polygamous marriage’ between local religion and the alien Islamic and Christianity faiths as were employed during the Majimaji resistance and have been used in contemporary social, cultural, and political terrain.

Cult as a term is widely used as a stereotype. The original meaning of cult is from Latin

cultus, which means worship in a more or less neutral sense (

Ellwood 1986). But scholars, such as Kevin Christiano, William Swatos, and Peter Kivisto, restrict its uses by modem social scientists in academic literature, calling it an ethical breach (

Christiano et al. 2002, p. 11). As such, terms, such as alternative religious movements, emergent religions, marginal religious movements, and new religious movements (NRMs), have been suggested to take the place of cult (

Harper and Le Beau 1993). Despite the critiques leveled against the use of the term, this study finds cult useful to explain the Majimaji situation and how local religion, Christianity, and Islam are intertwined in matters of violence and the remedying of the German colonialism in Tanzania. African belief systems permeate a person’s entire life, such as sacred moments, rituals, morals, customs, and social institutions (

Titova et al. 2017). The Majimaji War was organized around pre-existing beliefs in water cults by a ritualist, healer, and religious leader Kinjekitile Ngwale. For this, the Majimaji War managed to unify more than twenty different ethnic groups geographically located faraway from one another from the southeastern coast of Tanzania to its interior (

Rushohora 2015). The medicine famously known as

Maji from which the war obtained its name, was spread as a cult propagated through emissaries called

hongo. It should be noted that the extent of spread of the Majimaji War was beyond the limits of pre-existing water cults previously carried by the same agency (

Gwassa 1973). This attests to the notion that African belief systems are not primarily for the individual but for communities, particularly in difficult times (

Masebo 2014).

After this introduction, this paper is organized into four sections. The section titled Maji Cult Continuity details the continuity of the water cult in fighting injustice. The section Majimaji and Religion details the relationship between the Majimaji War and religion. In the subsequent section, the discussion concerns religion as it has been employed in physical and metaphysical healing. The section titled War Memory and Remedy presents the memorialization endeavors intertwined in the concept of remedying the colonial violence. The last part of the paper provides the conclusion.

2. Maji Cult Continuity

The Majimaji War water cult—

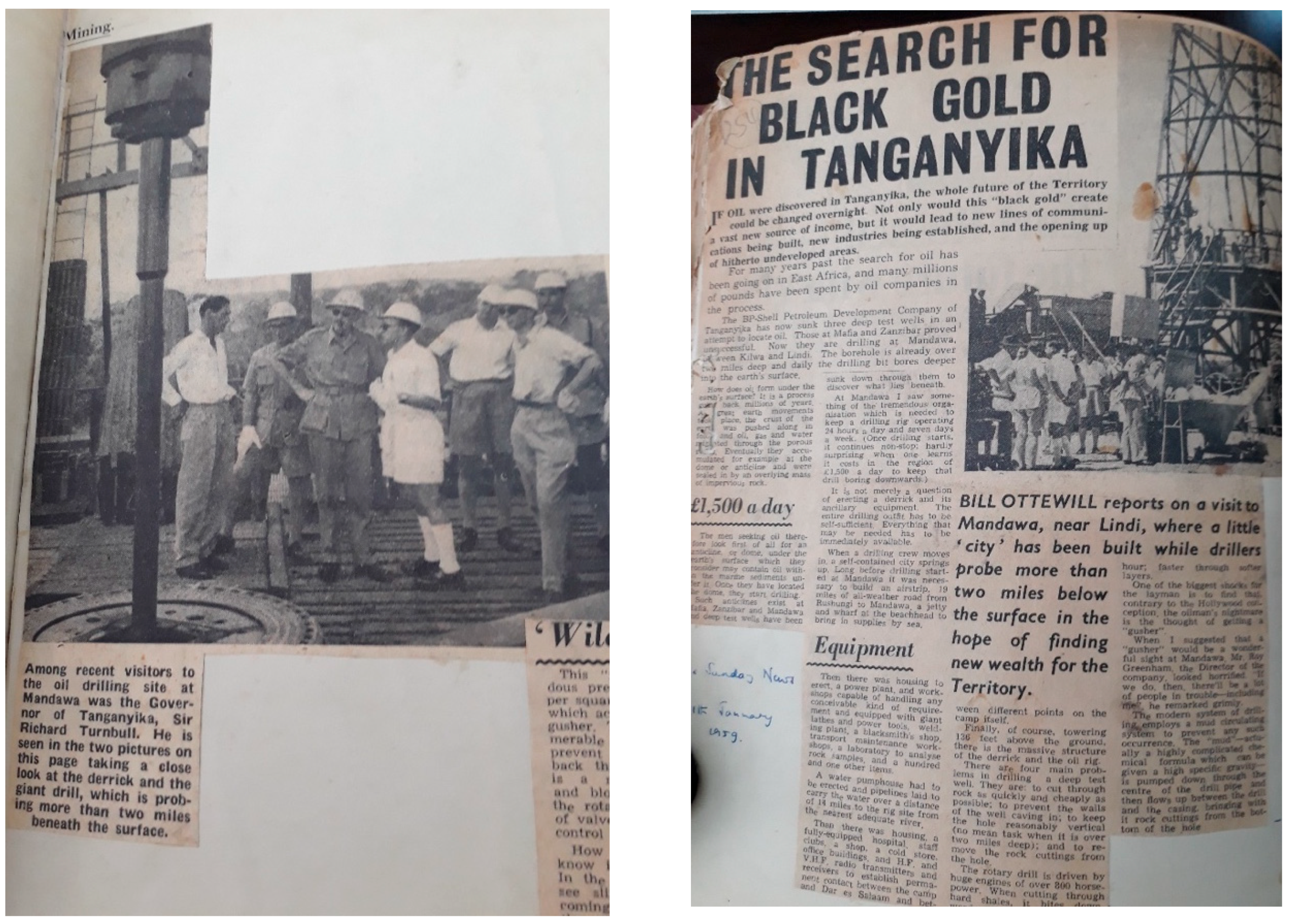

Maji—was evoked during the 2012–2013 protest against the pipeline transportation of natural gas from southern Tanzania (Mtwara Region) to the northeast (Dar es Salaam Region). The economic development of southern Tanzania and what was to become the gas metropolis of Lindi and Mtwara collapsed as the government decided to pipe the gas to Dar es Salaam, leaving the echo of the name alone in southern Tanzania. Tanzania had depended on hydroelectric power as a national energy strategy until the late 1990s when a switch to natural gas as a supplement occurred. The history of natural gas exploration, discovery, and exploitation began in 1952. Categorically, the period 1952–1959 saw the British colonialists searching for gas and oil, alternatively named black gold (

Figure 1), on the eastern coast of the Indian Ocean. These explorations, however, led to no discovery of commercially viable hydrocarbon. After independence in 1961, a state-owned petroleum company, named Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC), was established in 1969 and the search for natural gas was resumed in 1970s along the southern coast of Tanzania (

Samji et al. 2009). In 1974 a natural gas reserve was discovered at Songosongo and later at Mnazi Bay in 1982. In 2004, the Songosongo gas was piped to the power plant constructed at Ubungo, Dar es Salaam a distance of approximately 225 km. In the period 2012–2013, approval of a 524 km gas pipeline from Mtwara to Dar es Salaam was initiated. Piping the gas to Dar es Salaam seemed impractical in the eyes of the people of southern Tanzania because the region remained one of the poorly served regions for national electricity coverage. Electricity supply in southern Tanzania remained unreliable (

Samji et al. 2009). Unlike Songosongo, Mnazi Bay gas piping triggered violence in the region (

Figure 2). Similar to the Majimaji movement, the gas saga united the people of southern Tanzania to resist the project on the grounds that it would not benefit the ‘southerners’. Gas exploration was initially seen as the only window for the economic development of southern Tanzania. Piping the gas, therefore, jeopardized their dream for development and perpetuated the longstanding economic marginalization of southern Tanzania. The gas protest emerged first in the form of peaceful demonstrations, but later it became violent only to be suppressed by the Tanzania People’s Defense Force (TPDF).

Behind the entire gas saga was a ritualist Bibi Samoe Mtiti from Msimbati village, famously known as Bibi wa Msimbati, who was believed to be aged 106 during the protest. Like Kinjekitile, Bibi wa Msimbati cautioned the government that any attempt to pipe the gas elsewhere would turn the gas to water. The ritualist also warned about the possibilities of the gas reserves disappearing into the Indian Ocean. Bibi wa Msimbati drew a good number of followers and believers. Although she was a ritualist before the beginning of the gas protest, immediately after the outbreak of the riots, her popularity went beyond Msimbati and caught the attention of the rioters, media, and even government officials. In an attempt to pledge for peace in Mtwara region, for example, the then Prime Minister, Mizengo Peter Pinda, visited her. This visit by the Prime Minister counteracts the government cynicism that disregards rituals by law.

There are patterns of both similarity and difference between the Majimaji and the gas piping protests. Unlike Kinjekitile,

Bibi wa Msimbati did not promise immunity against bodily harm. As a result, some people migrated to Mozambique to evade the violence. The migration was temporary, but there is a continued pattern of forced Makonde migration between Tanzania and Mozambique during insecurity (

Liebenow 1971). It was reported that twelve people died, women were raped, many people were tortured, and property destroyed (

Ndimbwa 2014). The continuity of the

Maji ritual as attested by the cult belief in the possibility of a natural substance being turned into water, explains the persistence of rituals in southern Tanzania. Kinjekitile’s

Maji, we argue, did not end with the military defeat of the war, rather it sprouted a strong water cult capable of unification, eradication, resolution, and a solution to problems of nature, politics, and the fight for justice.

Continuity between

Bibi wa Msimbati and Kinjekitile is very important to claims of identity and legacy of the Majimaji War ritual. Justification for this is in the description of

Maji that suitably suggests a form of teaching beyond the materiality of the medicine. This teaching is passed on from one person to the other, and plausibly inherited from generation to generation (

Monson 2010). As part of the southern Tanzania historical narrative, a tale of the function of

Maji suggests that it is a powerful weapon used both during and after the conflict demonstrated by the unification function that the ideology has performed in mobilizing the political agenda on the one hand and the transformative power among societies in southern Tanzania communities when experiencing danger and hardship on the other.

3. Majimaji and Religion

In the early twentieth century in Africa, religions were mostly Europeanized (

Bevans and Schroeder 2004) to represent Christianity (

Isaak 2018;

Ana 2005). As such, religious ideology was one of the components of African resistance to colonialism. Most of these resistances were guided by religious ideologies. For example, the Majimaji War in Tanzania was guided by the

Maji ideology. The Chimurenga War in Zimbabwe had a

Mwari cult (

Ross 1979). Samori Toure resistance in present-day southern Mali/Guinea and the Mahdist War in Sudan had Islamic jihad ideologies (

Msellemu 2013;

Sanderson 1969). In Chimurenga, numerous hostile groups fought together against the whites; the war itself had different names as the Ndebele call it Umvukela while the Shona call it Chimurenga (

Makuvaza and Makuvaza 2012). Samori Toure’s resistance grew out of his harsh regime. Thus, he forced his neighbor’s collaboration into colonial resistance (

Peterson 2008). This was possible because of the ability of ideology and rituals of the area to motivate, facilitate, and coordinate resistance (

Ross 1979). Religious ideologies were sometimes borrowed from or influenced by the neighbors’. The Mahdist ideologies present such a case by the spread of the ideology in a vast region of the Islamic communities from the Horn to West Africa (

Ibrahim 1979). Religious ideologies also served as a unification point and mobilization for large masses of people from numerous political units. Looking particularly at the Majimaji (

Iliffe 1979), Chimurenga (

Ranger 1967), and Samori Toure (

Jansen 2002), we see that societies which shared an experience of adversity achieved mass organization against colonialism. In the case of Majimaji, the people of southern Tanzania spoke several different languages and were antagonistic to the Ngoni (

Giblin and Monson 2010). Moreover, it was not only in these great resistances that religious leaders were of importance. African resistance was often expressed in ‘messianic movements’ and religious upheavals, which marked the first adjustment to colonial authority (

Denoon and Kuper 1970). This was how the masses were mobilized to fight colonialism (

Fernandez 1978;

Ranger 1986;

Ellis and Ter Haar 1998).

The use of the

Maji cult in the organization of the Majimaji War was so effective that it was believed to have been the work of outsiders with the implication that Majimaji peoples and societies could not have been capable of such a feat. On the one hand, Herr Eduard Haber, the then German Chief Secretary in German East Africa claimed that the war was controlled in a logical manner plausibly by an

askari (police/soldiers) or an Arab leader (

Gwassa 1969). Yet Haber was unable to explain why and how the

askari or individual Arab could have decided to fight against the Germans and be able to mobilize such a vast population. On the other hand, the Majimaji War has been associated with alien religious ideologies, such as Christianity and Islam. However, it is hard to conceive the idea of an alien religious ideology per se, particularly from the side of Christianity. The first outbreak of the Majimaji War was in Umatumbi. In this area, missionaries had never been settled anywhere before or during the Majimaji outbreak. The first mission in Umatumbi was established in 1910 at Kipatimu, three years after the Majimaji War. In Liwale, which is another familiar Majimaji battle site, no mission station existed until 1964 (three years after Tanzania independence). This research found out that in Ngarambi, which was the origin of the water medicine (

Maji), there was no established mission in 2015. Therefore, the influence of Christianity cannot be confirmed.

Contrary to the European induced Christianity, Tanzania was under the influence of the Arabs before the European conquest, and Islamic religion coincided with this establishment. The Arabic rule and Islamic culture had acquired a high social status, especially among the African elites and coastal peoples during the Majimaji outbreak. Kinjekitile Ngwale’s prophecy pinpoints that the overthrow of the German administration would be replaced by Seyyid Said’s (Arab) authority (

Hussein 1969). This suggests that the Majimaji War was multidimensional. The belief in water-

Maji remained prominent throughout the war; however, its administration was associated with different religious practices. For example, Nduna Songea wrote a letter to his Yao neighbor, Chief Machemba, to invite his people to the war and convinced him that he had sent a bottle from ‘prophet Mohamed’, which contained the medicine which served to defeat the Europeans. Whereas, the application of the water medicine was recounted as baptism (

Monson 2010).

Missions and missionaries were the targets of war in Nyangao, Lukuledi, and Peramiho areas in southern Tanzania. From the beginning, the Majimaji intended to correct the thoughts and beliefs of the Christian followers. It was like a movement purposely intended to destroy the Christian faith and the work of the mission. Only 1% of the Christians joined Majimaji at Lukuledi (

Napachihi 1998) and not more than 5% at Nyangao (

Hertlein 2008). Whenever possible, all mission buildings and even all schools were burned. The missionaries and the faithful Christians were hunted and killed (

Rushohora 2017). In some places, the missionaries had been so successful that converts tended to be against the Majimaji War and supported the missionaries when attacked. This happened in Masasi where the Anglican missionaries had been established since 1876. Masasi is predominantly occupied by the Yao and Makua people. Chief Nakaam welcomed and encouraged the missionaries, allowing his nephew and heir-apparent to be sent to Zanzibar, for religious and formal education, where he was baptized Barnaba Mwatuka. His conversion and subsequent accession to the throne were to be great assets to the Anglican missions in the area (

Malishi 1987). Very few Christians joined Majimaji or actively helped to destroy the missionsor hunt the missionaries even when subjected to extreme pressure.

While missions, churches, colonial government headquarters, and homes of German settlers and traders were plundered and set on fire, no mosque was attacked or set ablaze. The Islamic nature of the war is emphasized by the fact that the prominent Majimaji warriors and leaders were Muslims. Yet Arabs and Muslims were not immune to attack. Most of the Arabs were regarded as traders or associates of the German colonization. Thus, they were attacked, and some of them were killed (

Larson 2010). Considering Christianity and Islam alone in the Majimaji scenario without the cult is perplexing. Individual Muslims joined the Germans to fight against the Majimaji warriors. Masoud of Kikole in Ungoni, for example, fought against Chief Mputa and his slaves joined the German army during Majimaji (

Rushohora 2015;

Mapunda 2010). In some battles, the leaders of the Majimaji War were Christians; take the case of Gabriel Mbuwu of Umwera. All these complexities stress how understanding religious patterns of colonial violence change historically and how important it is to understand social agents and their identities which may as well not be static but historically transient and shifting (

Johnson 2002).

4. Religion and Healing

There has been an increase in the studies related to religion and development, religion and healing, and/or health and religion as an inspiration for political change especial in the early 20th century through to post-colonial Africa (

Olivier 2016). Recent studies in Sub-Saharan Africa have shown that the majority of believers consider religion as an important part of their life (

Kar 2008;

Levin 2009), and the number of religious believers within the world religions is growing faster in the Global South than the West (

Freeman 2012) partly due to the lack of reliable biomedical healthcare infrastructures. Of interest in Tanzania is the Catholic church alignment of her health care policy (biblical) with that of the government by “…continuing with the healing ministry of Jesus Christ by providing a holistic, quality, and sustainable healthcare….” (

Tanzania Episcopal Conference 2008, p. 4). Equally, religious leaders of different denominations (mostly during the post-colonial era) stress the prosperity gospel and that it is essential to healthcare delivery and affluence (

Setswe 1999).

Religion and faith healing practice is an important aspect of the health care literature, especially when individuals start seeking an alternative treatment for their different maladies. Studies in West Africa have shown that faith healers served as the first port of call for malady curing and prevention (

Peprah et al. 2018). Followers and faith congregations perceived their health to have improved as their faith effectiveness increased. Although there have been some critics of faith health and healing, such as stigmatization and victimization, scholars have called for policymakers to integrate policies that allow formal medical services to have an open mind to faith healing practices (

Setswe 1999). The use of the religious practice of faith healing in the diagnosis, for prevention and treatment of a plethora of health issues, and even social problems, dates back into antiquity (

Thacore and Gupta 1978;

Wardwell 1994;

Kale 1995). The believers of faith healing and health, as well as faith healers, believe that their healing power comes from God through the Holy Spirit and/or ancestral spirits (

Peprah et al. 2018).

Among the eastern Bantu language speakers,

Ganga is the root word that denotes physical and psychological healing (

Feierman 2006). Throughout the pre-colonial and during colonialism, Europeans attest encounters with a cult or

uganga as a form of healing for all human and societal predicaments. Colonialists faced extreme resistance to the integration of African healing practices into the colonial system. Colonialists created ordinances to control the application of a cult against the state, as was the case during the Majimaji War (

Alexander 2012). African healing was an office under the political leadership with supreme control over the social wellbeing of the polity. Healing, thus, was of the people as individuals and families both dead and alive, their land and the land of their ancestors where migration is involved and more specifically for diagnosed maladies in the society. Healing, therefore, is considered, for the sake of this paper, as both a local knowledge or skill and a belief system or religion—indeed a cult as presented in the preceding section. The longevity of the knowledge is sustained orally from one generation to another, and this knowledge is jealously guarded by each culture. Due to the vitality of religion, cults, and associated divinities, scholars have sought interventions as a conservation tool particularly for the sacred creed and the landscape destined for occult practices, healing, and plants/animals related to the same (

Kangalawe et al. 2014).

The African perception of healing is not based on a singular form. For anything that inflicts individuals as members of the community, intervention is sought from all sources available until healing is achieved. Seeking healing from neighboring or distant ritualists belonging to a different culture is, therefore, a very common practice. This applies to Christianity and Islam (

Masebo 2014). This section presents the use of the

Maji cult for the healing of colonially inflicted challenges.

Maji was a natural substance that entered the Majimaji War—a resistance against the German colonization of southern Tanzania—as ritualized librettos. Although Maji means water in Kiswahili, as a cult,

Maji is not synonymous with water but a war medicine in liquid form. Its content contained water and other herbs and was applied by bathing, sprinkling, or spraying the warriors (

Gwassa 2005). Originating among the Mwera where Kinjekitile belonged, the

Maji medicine spread throughout southern and eastern Tanzania communities which were united by their eagerness to eliminate colonialism. The medicine, thus, was for immunization, cure, and protection of the Majimaji War fighters, their families, and properties. In fact, it was the medicine of immortality strongly attached to the belief of turning a natural substance into water—in this case, bullets.

One of the outstanding questions about

Maji medicine has been the longevity of rituals despite tremendous deaths that southern Tanzania communities faced as the result of the medicine’s failure to protect the fighters and their properties. Adherence to

Maji medicine was attached to ritual effectiveness guidelines. Abstinence, for instance, was a must for both warriors and their associated wives and concubines. Failure of the medicine was, thus, attributed to nonadherence to the guidelines, rather than the medicine’s prowess. Rumors of survivors who adhered to the guidelines appropriately spread during the war and inspired resistance elsewhere. Before

Maji was accepted in Ruvuma, Chief Chabruma had to establish the legitimacy of the medicine. To do so, the chief called all the ritual experts, including his own diviner, and tested the medicine, first on a dog and then on a man convicted of adultery. On both occasional tests, the

Maji failed. Yet Chief Chabruma accepted it and ordered his people to do the same (

Rushohora 2015). Explanation of the

Maji failure during the testing by Chief Chabruma was offered by Kinjala—the

Maji messenger—that it was due to the circumstance under which the

Maji was prepared. The medicine was meant for war and not convicts or non-human beings (

Mapunda and Mpangara 1969). Interviews in Umatumbi which were conducted in 2007 attest that three Majimaji warriors namely Ngulumbalyo Mandai, Lindimyo Mcheka, and Ngumbalio Machela Mbonde who were among the first recipients of

Maji medicine from Kinjekitile Ngwale, died a natural death. The three instigated the war in July 1907 by uprooting cotton seedlings in the colonial plantation located in Nandete.

The durability of rituals in southern Tanzania is very distinct. Evidence suggests fatal consequences of ritual beliefs evidenced not only by the loss of life but also marginalization that has rendered the region a Cinderella of the country (

Liebenow 1971). Rituals have been used as a tool for politically and socially driven movements prevalent in the region. Perseverance of rituals is also important because it was one of the treasures that were hunted during colonialism, supposedly to be eradicated through colonial education, foreign religion, and modernity (

Moore and Sanders 2003). This definitely failed, and rituals have remained idiomatic for life experience and resultant reactions from the same (

Mesaki 2009).

Rituals in southern Tanzania cut across gender and religious divides to assume the communities’ needs. Both male and female members of the society are agents of rituals performing different functions to ensure the successfulness of the plea. Age, however, is an impinging factor among women ritual partakers, giving preference to post-menopause women as desirable candidates for ritual performance. Participants of rituals range from an individual ritualist, a small group of ritualists and leaders as well as heterogeneous groups of women who participate in

ngoma (dance). In the wake of Christianity and Islamic religions, rituals have a stronghold beyond the alien faith. A Catholic catechist in Umatumbi, for example, is also the head of the family ritual, a title congenital by merit of being the firstborn child in the family. Apart from having Christianity and Islamic forms of religion, the people of southern Tanzania practice rituals and cults. Christianity and Islam are considered both a colonial and foreign religion. An interview in Ruvuma captured this notion by referring to Christianity and Islam as belief in colonizer’s ancestors, whereas local religion was the belief in ‘our’ (African) ancestors. African rituals are the inheritance of ancestors for the propagation of the society. A survey of the Majimaji War landscape indicates a conglomeration of religion unified by ritual practices. Ritual huts, trees, and caves, mass graves, Christian cemeteries, and memorial Mosques all occur in the war landscape and directly influence spirituality of the descendant communities that seek healing from the colonial past (see

Figure 3). Although these belief systems are apparently antagonistic, they are enculturated as one form of ritual in seeking healing. The cave Chandamali which was used by the sub-chief Songea Mbano as a refuge during the Majimaji War has carried a significant meaning among ritualist in the Majimaji region. It is used to enact the power of ritualists (

waganga), commemorated as a heroic space, and as a source for freedom from all ailments. As a ritual site, the cave is feared. Thus, a survey of the area was impossible without conducting rituals to appeal to the ancestors. A survey of Chandamali indicated several pseudo entries into which one had to crawl, but they were blocked after two to three meters. The true entry is at the western point. The commencement is a crawl space which after 3 m allows bending and standing after 5 m. Pottery and lithic materials were observed by the entrance to the cave and scatters of ashes indicating burning, which is part of the rituals.

5. War Memory and Remedy

Memorialization of the Majimaji War follows the three faiths, namely local, Christianity, and Islam as a basis for healing. In this section, a live experience of memorialization of the Majimaji War and encounter between the local religion, Christianity, and Islam as a remedying strategy from colonial induced violence is brought to the fore. This performance prevailed on 25–27 February 2019 during the annual commemoration of the summary execution of the Majimaji Warriors in Ungoni. The execution took place on three dates: 27 February, 20 March, and 12 April 1906 (

Schmidt 2010) and the victims of the gallows were buried sequentially in a mass grave that the prisoners of the war prepared before their execution. Mass graves do not represent southern Tanzania burial rites. Graves of forefathers are designated at their families’ burial places; the mass grave has been a symbol of all who died during the war. It is estimated that the mass grave holds 100 bodies. Nevertheless, among the Ngoni, scarcely a single family exists today that did not lose members either by execution or war perils between 1905 and 1908. Commemoration of the German execution of the Majimaji warriors among the Ngoni unfolded in three different events: at the mass grave of the Majimaji War victims where a ritual is conducted overnight to appease the ancestral spirits. The Catholic holy mass performed on 26 February at the residence of the Ngoni chief. The mass is conducted as a mortuary rite in the Catholic faith. The priest summons is based on the Majimaji victims who were baptized thirty minutes before their execution and refers to them as martyrs who were ready to die in defense of the country against violence, exploitation, and cruelty—all of which are against God’s will. The third is the commemoration event where Christian priests and Muslim Sheikhs are called on to offer prayers for the Majimaji victims. This intermingling between local religion, Christianity, and Islam in commemorating the violent past in a celebration which is politically sponsored by the government of Tanzania presents an interesting case of memory and remedying the colonial violence.

Ritual constitutes a fundamental part of the commemoration activities of the Majimaji War. Although the commemoration is, in essence, local, the aim of which is for the Ngoni to remember the lives lost during the Majimaji War, aspects of religion and politics percolate the entire event. The commemorations, which run for three days, are devoted to different activities. Foremost, is the public gathering where different topics are discussed, and members of the public respond to the presentation by questioning different episodes of the war. It is here that transgenerational memories of the war are evident and demands for repatriation and reparations are discussed (

Rushohora Forthcoming).

The discussion is preceded by visiting the Majimaji War sites. The pattern of these sites also represents the entanglement of religion in the Majimaji event. These sites are Chandamali, which was a refuge for the sub-chief Songea Mbano who was the Majimaji War general for the side of Ungoni. Chandamali is currently a ritual site. The Majimaji War Museum, which is a government-owned onsite museum established where the mass grave and the grave of the sub-chief Songea Mbano is located, is also visited. The museum exhibits photographs of the Majimaji warriors of other parts of southern Tanzania, such as Selemani Mamba who was the leader of the war in Umwera in Mtwara and Abdallah Mchimaye, the leader of the war in Ungindo in the Lindi region. Another site also visited as part of commemoration activities is the Peramiho Catholic Church and Maposeni residence of Chief Gwazerapasi Gama. The Peramiho church is significant for the Majimaji in Ungoni because the war was instigated there. A Catholic priest Fr. Fransiskus destroyed a ritual hut which belonged to the Chief Gwazerapasi Gama accusing him of worshiping idols (

Schmidt 2010;

Mapunda 2010;

Rushohora 2017). In revenge, the Ngoni burnt Peramiho church. Concomitantly, Maposeni was the residence of the chief. It was also the place where Fr. Fransiskus was killed (a memorial was constructed) and a place where the ritual hut that the priest burnt was located. This list provides a summary of some of the important Majimaji sites in Ungoni.

As part of the commemoration activities, a ritual is conducted on the night of 26 February preceding what was the first execution of the Majimaji victims in Songea—27 February. A bull is bought through the sponsorship of the Tanzania local government. The ritual is conducted by leaders who are women and men including the grandson of Songea Mbano first on the bull before slaughter, then on the mass grave and the grave of sub-chief Songea. This is followed by the Catholic repose of souls—a Catholic ritual which is performed at the residence of the Ngoni chief. This ritual is steered as part of the mortuary rite in the Catholic dogma and doctrine as reflected in the liturgy surrounding the death and burial of the faithful. In 2019, the priest summons focused on the Majimaji victims of the gallows, particularly those who were baptized thirty minutes before their execution as martyrs. These victims were ready to die in defense of the country against violence, exploitation, and cruelty—all of which are against God’s will.

The last day of the commemorations is an official government commemoration ceremony. Government officials of different ranks ranging from presidents, ministers of tourism, ministers of defense forces, commanders of defense forces, German ambassadors and regional commissioners have attended this event. Two presidents, namely Julius Nyerere and Jakaya Kikwete, have attended this commemoration ceremony. The ceremony begins with the placing of a memorial wreath on the memorial constructed at the gallows then at the mass grave. The two sites are located at a distance of half a kilometer apart. It is at the mass grave that prayers from different congregations in Tanzania are unveiled. Bishops, Priests, and Sheikhs pray on the mass grave. These prayers are mixed with sorrow and victory that the Majimaji victims endured. The mass grave has remained the major symbol for those who died during the Majimaji War. This is because uncontested graves of the Majimaji War are few (

Rushohora 2019). The Tanzania people defense force partake in these commemorations annually. The history of the army is traced from the Majimaji War, and it was from the blood of the Majimaji victims that Tanzania as a country was built. In honoring the Majimaji victims, the army uses a gun salute for these heroes of the country. Overreliance on religion in the forms of cults, Islam, and Christianity during commemoration activities relate to cleansing rituals from colonialism and the havoc that it caused to the colonized communities. Rituals offered on graves, caves, residence, and designated ritual houses are sought as an intervention to heal the land and the people. Spirits of the ancestors who died in colonial violence and never buried, for instance, are believed in African culture to be wandering spirits who can cause havoc to the living (

Werbner 1998). Spiritual intervention is, thus, an important remedy in the context of the Majimaji War. The relationship between rituals and society expressed above allows the explanation of spirits as the cause of misfortune. Cases of misfortune in cults and local religion signify a breach of relationships between the living and their ancestors either deliberate or unintentional. The bull slaughtered during the day preceding the commemoration activities is for reparation.