Abstract

Over the last decade, many scholars have explored the thesis of the mediatization of religion proposed by Hjarvard and how mediatization has impacted religious authority. While some scholars have underlined the increasing opportunities for marginalized religious actors to make their voices heard, others have explored how mediatization can also result in the enhancement of traditional religious authority or change the logic of religious authority. Against this background, in this paper, I focus on Christian LGBT+ digital voices in Italy to explore how they discursively engage with the official religious authority of the Catholic Church. The analysis adopts Campbell typology of religious authority. It highlights the complex balance between challenging and reaffirming traditional religious authority, and points out the role of the type of digital community in exploring the effects of the mediatization of religion.

1. Introduction

Religious LGBT+ actors usually exist in the periphery of their religious communities—this is the case for LGBT+ groups within the Roman Catholic Church1. Their presence is not officially acknowledged by the Catholic Church, which impacts their self-definition as “Christian” rather than “Catholic” LGBT+ communities. At the same time, these groups are active in some local parishes and religious associations.

Over the last decade, many scholars have explored the impact of mass media and digital technology on religions and, especially, on religious authority. While some scholars have underlined the increasing opportunities for marginalized religious actors to make their voices heard, others have explored how mediatization can also result in the enhancement of traditional religious authority.

In this paper, I focus on Christian LGBT+ digital voices in Italy to explore how they discursively engage with the official religious authority of the Catholic Church. The analysis highlights the complex balance between challenging and reaffirming traditional religious authority, contributing to the research on the effects of the mediatization of religion.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the theory of the mediatization of religion and how it impacts religious authority, and Section 3 focuses on the analytical framework and methodological approach. Section 4 describes the Italian context of mediatized religions, which constitutes the background for the presentation of the research results in Section 5. Section 6 presents a discussion of the results.

2. Theoretical Background: The Mediatization of Religion and Religious Authority

Mass and digital media influence the place of religion in contemporary societies with respect to the circulation of information about religions and the dissemination of religious products, values, and ideals (Lövheim and Lynch 2011). The development of mass and digital media has provided new tools for communication and information, thus influencing the process of mediation. Over the last decade, scholars have discussed whether it could be argued that this development has influenced, indeed, the overall institutional and individual logic of communication, and they have introduced the concept of mediatization to indicate “the social and cultural process through which a field or institution to some extent becomes dependent on the logic of the media” (Hjarvard 2011, p. 119). Therefore, the media enables, limits, and structures actors’ and institutions’ communications and actions (for a thorough discussion on mediatization as a concept, theory, research program, and paradigm, see (Lunt and Livingstone 2016).

The process of mediatization is particularly relevant in the case of religion, which indeed can be defined as a specific medium of communication. Enzo Pace outlines three forms of mediation (Pace 2009). The first is the mediation between the divine and the profane through mediators who hold symbolic codes. The second form of mediation concerns individuals who recognize and share these symbolic and ritualized communication codes. The third form of mediation touches upon the community of faith and the broader society, and it constitutes a form of public communication. According to the theory of the mediatization of religion advanced by Stig Hjarvard (2008, 2011, 2013), the mediatization process impacts the mediation role of religions and, thus, religious authority in different ways.

First, the media became the first and most important source of information on religion (Hjarvard 2016). Mass and digital media have popularized and disseminated specific visions of religion that contribute to shaping our image of religion via popular media products (such as television series or documentaries), news reports, blogs, websites, and the like. Mass media can also increase the visibility of marginalized religious groups or minority groups within majority religions (Højsgaard and Warburg 2005), thus legitimizing other voices with respect to official leadership. If we consider other media outlets and, specifically, digital environments, we find that digital media outlets offer minority groups the possibility of networking, audience building, mobilization, and voice channeling, thus increasing the opportunities for different voices to emerge (Cheong 2012; Hoover 2006). Different media outlets and digital platforms have different degrees of centrality and form a complex networked system, which is also an arena of competition for visibility and authority between majority and minority religions, between minority and majority groups within the same religion, and between different media outlets. In this sense, religious actors have to adjust to the media logic (Moberg 2018; Sumiala-Seppänen et al. 2006), and at the same time, they also actively use the media outlets and logic (Lövheim 2011).

Second, “Existing religious symbols, practices and beliefs become raw material for the media’s own narration of stories about both secular and sacred issues” (Hjarvard 2011, p. 124). This availability contributed to the popularization of expertise on religion. In this sense, unofficial voices and ordinary faithful are considered to have the expertise and, sometimes, the authority to speak about or on behalf of religion (Clark 2011a). David Herbert (2003, 2011, 2015) points out that this availability of religious materials also affords other actors the opportunity to appropriate and reframe religions for non-religion purposes. Clear examples are the public discussion on the role of Islam in European societies (Amiraux 2016) or the political mobilization of religious identity in the populist discourse: regardless of the official religious authorities’ positions, political leaders can provide their interpretation of religions (Giorgi 2019; Wagenvoorde 2019). Knoblauch (2008) frames it as the ‘culturalization’ of religion, through which religious symbols and topics have become part of the popular culture.

Third, the cultural and social environments of mass and digital media have partially overtaken some of institutional religions’ functions: they produce religious—or religious-like—experiences, provide moral guidance, and create a sense of community. Especially in digital media environments, unofficial religious voices can become authoritative actors in specific communities, challenging traditional and institutional authority. Mia Lövheim, for example, discusses the case of a blog for young Muslim women (Lövheim 2008, 2012a, 2012b). Marginal voices, such as those of women, LGBT+ people, or practitioners of minority religions, can find opportunities for visibility in the digital sphere (Aune et al. 2008; Huang and Chan 2015; Lövheim 2013; Tomalin et al. 2015). Moreover, unofficial religions and non-institutionalized groups can find safe places to meet and network online; in this sense, the effects of mediatization on institutionalized and non-institutionalized religions are different (see for example Boutros 2011 on Vudou).

Hence, the process of mediatization contributes to challenging the official religious authority as the only relevant medium of the sacred. Unofficial and marginal voices within religious communities and authoritative voices outside of religious communities and even outside of the religious field (such as in the case of populist leaders mobilizing religion) have capitalized on the availability of different sources of religious authority. Additionally, digital communities and mass media ceremonies offer alternative places for experiencing religion and provide alternative sources of information, thus challenging the official religious authority.

Hjarvard (2016) points out that the mediatization of religion also impacts the forms of legitimation of authority. Considering Weber’s classic typology, authority can be traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal (Weber [1922] 1978). Religious authority is primarily charismatic, although it resorts to other forms of legitimation over time (both traditional and rational-legal). The process of mediatization favors charismatic authority (Horsfield 2012) and what Clarks defines as “consensus-based interpretive authority” (Clark 2011a). The latter accounts for interactive and communitarian forms of authority outside the scope of Weber’s typology, which was primarily concerned with organized and institutionalized hierarchies. Instead, the media allows higher degrees of intervention, especially in digital communities and social networks (for a discussion, see Hjarvard 2016). Finally, the impact of the process of mediatization on religious authority combines with the broader process of decline of religious authority over the faithful, which, according to Chaves, is the core of the secularization process (Chaves 1994).

Charles Taylor points out that the secular age in which we live structures the conditions of the experience of religiosity, and individual choice has become a key feature of the contemporary religious and spiritual experience (Taylor 2007). From this perspective, a recent branch of literature that discusses the impact of mediatization on religious traditions recommends using the concept of “medialization” to underline “the reasoned reality of the mental and conceptual combinations of media processes and the effects of these processes” (Bratosin 2016, p. 406; Sá Martino 2019; Gomes 2016). Bratosin (2016) proposes the concept of “post neo-protestantism” to advance the hypothesis of a gradual convergence in Christian religious experience, toward a “trans-organizational, trans-confessional, or even trans-religious [way] to live the faith” (Bratosin 2019, p. 184). According to the scholars promoting this theoretical perspective, the Christian conception of religious authority is undergoing profound transformations, increasingly emphasizing the importance of individual religiosity (for a discussion, see Tudor and Herteliu 2017).

3. Religious Authority in Digital Environments: Analytical Framework, Empirical Data, and Methodology

Religiosity in the digital environment has been explored widely in the past decade, especially focusing on blogs, forums, and social media and analyzing religious creativity, the individualization of beliefs, lived religion, and forms of techno-spirituality (e.g., Campbell et al. 2014; Enstadt et al. 2015; Hutchings 2017; Lövheim and Linderman 2005; Sumiala-Seppänen et al. 2006). The concept of digital religion has been introduced as an analytical tool to focus on how religions shape and are shaped by digital spaces and technologies (Campbell 2012a; for a literature review, see Campbell 2017; Campbell and Evolvi 2019).

The research on religious communities2 in digital religion studies can be divided into four stages according to Campbell and Vitullo (2016): a first stage of description and documentation; a second stage of classification; a third stage of analysis of how offline religious communities made use of digital platforms and technology; and the current stage focusing on the intersections and interactions between online and offline community practices. The research presented in this paper is situated in the fourth stage, and it focuses on the online activity of a particular community (which is the first stage of a larger project focusing on online and offline interactions). The empirical data are part of a larger digital ethnography on Italian religious LGBT+ online forums. Here, I focus on a Christian LGBT+ forum. Even though the members of the online forum are not only Catholics, Roman Catholicism is the background of all the conversations and the most discussed religion by far (see Section 4). In this sense, it can be framed as an unofficial Catholic community at the margin of the mainstream—a peripheral minority operating on a network of websites, Facebook pages, twitter accounts, and the like. Periphery seems to be a crucial theme for the current Papacy, as Ferrara (2015) notes. Beyond the reference to country of origin as a geographical periphery, Pope Francis praises decentralized worldviews, claims the necessity of looking from the peripheries to gain perspective, and encourages visits to the peripheries. In Pope Francis’ discourse, the peripheries are reconceptualized as multiple diversities and perspectives, in which alternative worldviews thrive (a polyhedron, as explained in the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium3). From this perspective, unofficial communities at the margins of the official digital sphere have the opportunity to create nuance in the understanding of digital religions and to give perspective to contemporary Catholicism and Christianity.

As Campbell and Vitullo (2016) observe, little attention has been paid to unofficial Catholic communities online so far (cfr. Sbardelotto 2016; Kołodziejska 2018). This paper provides a step in that direction by presenting a case study. I focus on a single case study which I consider an exemplary case study, or “typical”, according to Seawright’s and Gerring’s typology (Seawright and Gerring 2008). As noted above, I selected an Italian online community for LGBT+ Christians. Discussions in the community are organized into different sections, covering relationships with family, coming out, sex and sexuality, spirituality and religiosity, pop culture, and relationships with Christianity—which was the section that includes the most comments (N = 402 discussions and 5344 comments between November 2013 and April 2019) and on which my analysis in Section 4 is based. In this discussion section on relationships with Christianity, topics ranged from individual requests for advice and support to general discussions concerning theology and the Synod on the Family. In the community, Catholic and Christian LGBT+ identity was constructed and legitimized through selective reference to the official religious authority, which was negotiated, nuanced, and reframed in the process. My research explores whether and to what extent religious authority was challenged and questioned and which kind of religious authority was instead promoted.

I downloaded the online discussions and coded them through MaxQDA, adopting the typology proposed by Campbell in her study on the Christian blogosphere (Campbell 2007), which includes the categories of roles, structures, texts, and theology. The category of “roles” includes reference to traditional Church leadership roles or recognized religious authority figures, such as Jesus Christ, Pope Francis, and Saint Augustine, as well as local priests. The category of “structures” refers to the organization of religious groups, such as the Church, the Synod, and the Liturgy. The category of “texts” includes all the texts that were used to legitimize the arguments, such as the gospel, encyclicals, and the final document of Vatican Council II. The category of “theology” considers Christian and Catholic beliefs and practices, such as the Sacraments, God’s love, and sin. Words can be used to mean different things; for example, “Synod” was used to mean both the institution and the documents issued by this institution. Therefore, the coding process took into account the overall context of the discussion in order to categorize the information as accurately as possible.

In the online discussions, religious authority emerged as both an argument for validating one’s position and an object of analysis. The LGBT+ community showed profound and detailed religious knowledge, which was mobilized to support individual positions and, at the same time, explored and debated in order to inquire about what the different religious authorities say about homosexuality. In this paper, I focus on the type of religious authority to which the community members referred. I also pay attention to how specific religious authorities were mobilized to build the digital community identity and boundaries. I do not explore, however, the bottom-up processes of the emergence of authority as negotiated within the community or the role of digital creativity (Campbell and Evolvi 2019; Kołodziejska 2018).

In her account of analyses focusing on religious authority and the internet, Pauline H. Cheong (2012) reports that the majority of studies share the assumption that religious authority is eroded by online religious activities and adopt the concepts of disconnections between online and offline religiosity and displacement of religious authority (Campbell 2007; Dawson 2000; Mandes 2015; Turner 2007). In this sense, mediatization can also be interpreted as a form of democratization of religion, bringing about consensus and charisma, rather than tradition, as sources of legitimation (Clark 2011b; Cheong 2011; Tee 2019). Digital communities are indeed different from the religious institutions into which people are born (see Bratosin 2019): they are an expression of active citizenship (Sorice 2016)—communities of choice (Kołodziejska 2018). Religious digital communities are hybrid public–private spaces that encourage religious individualism and reflexivity, and they can be considered avant-gardes of change (Kołodziejska 2016). Rather than serving as vectors of the privatization of religiosity, they are, instead, places of collective reappropriation of religion—spaces for coping with the deficiencies of offline religious communities (Neumaier 2015; Kołodziejska and Neumaier 2016).

Comparatively fewer studies have adopted an approach focusing on the continuity between online and offline activities in a networked society, exploring how socio-technical developments can also effectively enhance traditional religious authority (Barker 2005; Campbell 2010a; Cheong et al. 2008, 2011). In this direction, some studies have also focused on how religious institutions have addressed controversial online practices or interpretations with which they disagree. Campbell (2012b), for example, explored the Vatican’s attempts to control its online channels of official communication by disabling the interactive functions of its official YouTube channel in order to preserve its image, Narbona (2016) and Guzek (2015) explored the digital leadership of Pope on Twitter, and Lynch (2015) analyzed the Vatican website. Other studies have focused on the changes in the styles of displaying religious authority in different media environments. Tudor (2019) analyzed the evangelical “Horizon of Hope” campaign, showing the logic of cross media convergence and challenging the hypothesis of transfer of authority toward the new media.

In summary, scholarly research has explored how the mediatization of religion has impacted religious authority and has shown that traditional religious authority is impacted by and adapting to the process of mediatization (and, according to some scholars, the logic of religious mediation itself is changing); different religious traditions are characterized by different processes; different types of religious authority are differently impacted by mediatization; and digital religious communities are avant-gardes of transformation. This paper contributes to this literature by focusing on an unofficial and peripheral Catholic community, suggesting that the type of community is also a relevant factor in exploring how the mediatization of religion impacts religious authority.

4. The Italian Context of Mediatized Religions

In contemporary Italy, religion has a prominent space in the public sphere: religion-related issues frequently enter the political agenda, religion-related topics are publicly discussed, and religious actors express their voices in different media outlets (Ozzano and Giorgi 2016).

Among the religious actors, the Catholic Church has the most prominent voice. First of all, it has a large audience: it is the majority religion, with 74.4% of Italians declaring themselves Catholics, and 27% regularly attending Sunday Mass or otherwise engaging in religious activities (for example, civic society associations), according to the 2017 Ipsos data4. Catholicism in Italy holds the role of a vicarious religion (Giorgi 2018, 2019): even though it is practiced by a minority of the population, its symbolic role holds (Garelli 2014; Pace 2013).

Second, the Catholic Church owns a powerful media system, composed of a capillary network of local diocesan magazines (and about 15,000 parochial bulletins) and local newspapers, as well as national media outlets, including the Vatican daily newspaper L’Osservatore Romano, the Episcopal Conference daily newspaper l’Avvenire, the Catholic weekly magazine Famiglia Cristiana (and 141 other weekly magazines), the Episcopal Conference broadcasting satellite network Tv2000, almost 35 local TV channels, the Vatican Radio and Radio Maria, and about 250 local radio stations (beyond the official press agency SIR—Servizio Informazione Religiosa). In addition, there are 42 missionary magazines, 650 media channels issued by associations and movements, 320 magazines devoted to the Sanctuaries, 422 magazines of male and female religious orders, other magazines on Catholic culture, 200 publishing houses, and about 200 bookstores (Ceccarini 2001; Zizola 2019). Although with some internal differences (Bertuzzi 2017; Ozzano and Giorgi 2016), these media platforms channel the official voice of the Catholic Church. In 1957, Pope Pius XII welcomed new technologies as a gift from God in the Encyclical Letter Miranda Prosus5 (and many specific guidelines were issued in the following years). With respect to other religions, quite interesting is the monthly magazine Confronti.net, issued by the Evangelical Federation with an interfaith editorial board covering religion-related topics as well as broader contemporary issues. Mostly non-Catholic religious traditions adopt media outlets addressing their internal audience.

Third, there is a large presence of both the clergy and prominent Catholic voices in non-Catholic mass media outlets. Research shows that until 2016–2017, Catholicism occupied between 95% and 98% of the TV space devoted to religions6. The voices of the Catholic Pope and the clergy are often reported, and/or they are invited to TV talk shows. The attention paid to Catholicism in the mainstream media is so dominant that one of the most important daily newspapers, La Stampa, runs a website completely devoted to Catholicism (VaticanInsider). Moreover, in TV entertainment, Catholicism is quite well positioned: among the locally produced TV series, Don Matteo (priest-detective) was the third most viewed show in 2018 (Auditel data), and The Young Pope had the most-viewed debut of any Sky TV series (Auditel data). The presence of religious symbols in advertisement is also particularly relevant, although it has changed substantially over the years (Nardella 2014). Comparatively less attention is paid to non-Catholic religions—mostly, they are featured in the news with respect to issues of folklore, immigration, and violence—especially Islam (Castelli Gattinara 2016; Giorgi and Vitale 2017). Research focusing on non-Catholic religions shows that the voices of non-Catholic religious leaders are rarely quoted (Bertuzzi 2017; Osservatorio Carta di Roma7; Ozzano and Giorgi 2016), although this is gradually changing (Giorgi 2017). When such religions are cited, it is usually official voices that are reported, whereas internal dissent is usually disregarded. Non-Catholic religions, from this perspective, are framed as internally homogeneous “others”.

Fourth, when political actors in the public sphere talk and write about religion, it is Catholicism to which they mostly refer. Since the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Christian Democrats—the main political channel for Catholic values—political actors have been vying to attract the supposedly dispersed Catholic vote. Center-right parties became the champions of Catholic values, upholding neo-confessional moral conservatism and promoting and defending ‘non-negotiable’ values (Bolzonar 2016; Diotallevi 2016; Ozzano and Giorgi 2016). Center-left parties instead gave prominence to Catholic social teachings and solidarity (Giorgi 2019). The populist discourse proposes a ‘militant’ and nationalist version of Catholicism—a supposedly shared identity to be defended from ‘invasion’ by immigrants, particularly Muslims (Guolo 2000; Molle 2018). With the exception of Islam, other non-Catholic religions are almost invisible in the Italian public and political discourse (Giorgi 2018, 2019).

The mediatization of Catholicism has intersected with the secularization process and the transformation of religious authority. As in other European contexts, the Catholic Church’s moral authority over the faithful in Italy has been declining (Chaves 1994), though to a lesser extent than in the northern European countries (Garelli 2014; Pace 2013). At the same time, internal secularization has resulted in the intensification of the differences and the competition between the many groups and souls composing the Catholic Church to the extent that some scholars have framed it as a “sectarian” Church (Marzano 2013, 2018). Thus, competing Catholic discourses and the Catholic Church’s internal diversity (Diotallevi 2002) have become more and more visible in the public sphere. Non-mainstream and digital media offer the opportunity for non-Catholic religious actors and/or internal dissenting voices to intervene and construct an alternative discourse, as discussed in the previous sections.

The Catholic Church started its online activities in the early 1990s, welcoming the digital world as a new forum for the gospel (Guzek 2015). The Vatican directly manages 78 websites and their related Facebook pages and Twitter profiles, as well as two official apps. The Pope has an official Twitter profile (@Pontifex) in nine different languages and an Instagram profile (@Franciscus). The different institutions of the Catholic Church have their own individual digital presence, such as the Italian Episcopal Conference and the Italian Caritas. At the local level, the majority of the dioceses have also set up websites, Twitter profiles, Facebook pages, and YouTube channels. With the exception of its YouTube channels and websites (see Campbell 2012b), the official channels of the Catholic Church in the social media sphere are open to interactions with the public. The level of interaction ranges from virtually none for some local dioceses and parishes to the almost 5 million followers of the Italian Twitter profile of the Pope, whose tweets usually collect thousands of likes. Among the different official channels, the official Facebook pages are the least frequented. In accordance with the findings of Sbardelotto (2016) for the Brazilian case, in Italy, comments bearing heavy criticisms or insults are usually not removed or moderated. In addition, those channels collect the voices of lay people who challenge the official authority and feel entitled to confront the Pope, as well as any other official voice. Thus, these platforms allow ordinary people to stand above the Catholic hierarchy and consider themselves the true interpreters of the Church doctrine, changing the traditional communication flow. At the same time, these social media platforms are also forums in which faith and its meaning in contemporary societies are discussed and negotiated. For example, one of the most popular topics of discussion raised in the comments on Pope Francis I’s official posts on Facebook concerns migration: while many commentators praise the Pope’s welcoming position as an example of Christian charity, others criticize it as a politicization of religion and capitulation to Islam.

The digital environment also offers a platform for peripheral voices, such as the Catholic LGBT+ community discussed in the following sections or minority religions (Giorgi 2018). Beyond official channels, the Italian-speaking digital sphere includes websites, blogs, YouTube channels, Facebook pages and groups, and Twitter profiles featuring alternative voices, such as an intersectional feminist forum on Facebook connected to a blog founded by an Italian Muslim woman or an LGBT+ website hosting information about LGBT+ Muslims, whose administrators also organize many local initiatives on awareness and dissemination of information. As it happens in other countries, web platforms provide opportunities to enhance individual agencies and the authority of alternative and usually powerless voices (Lövheim 2012b).

Traditionally governed by an all-male hierarchy, in recent years, the Catholic Church has witnessed a surge in the public presence and acknowledgement of women’s and LGBT+ people’s points of view, posing a challenge to the traditional religious authority both in terms of recognition and its position on gender issues. In the next section, I focus on the case of an online community of LGBT+ Christians.

5. Catholic LGBT+ Networked Communities and the Issue of Authority

Catholic LGBT+ groups have been active in Italy since the 1980s, often led by local priests (Turina 2013). The oldest is Il Guado (Milano), established in 1980. Indeed, it appears that the activity of such groups prompted the Catholic Church to issue a series of documents stating the Catholic official doctrine on homosexuality—such as the 1986 letter to the bishops on “the pastoral care of Homosexual persons” by the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger8 (Turina 2013). Up to that point, the Catholic Church’s position was to silence and marginalize the issue of homosexuality.

While it may be hypothesized that online forums have empowered marginalized voices and allowed them to establish and define themselves as a community—as in the case of neo-pagan groups (Giorgi 2018; see Fernback 2002)—the online presence of Italian Catholic LGBT+ communities stemmed from already existing offline groups. As Campbell underlines (Campbell 2012c), communities are built when there is emotional investment in the group, shared support, and perceived common identity, culture, and symbols. Indeed, such groups constitute a dense community network.

In Italy, in addition to six groups for parents with LGBT+ children and parochial groups addressing LGBT+ issues, there are about 30 LGBT+ groups in more than 20 cities, mostly located in the central northern region of Italy, and two official online communities (for adults and youth). Each group includes about 30 people. According to the last report on LGBT+ Christians in Italy (2015), about 530 individuals, mostly males (80%), participate regularly in the groups’ activities. Many groups (67%) are hosted by Catholic parishes, while the others organize their meetings in Waldensian and Methodist Churches, other religious buildings (such as Jesuit institutes), or places offered by the city council. A few of the groups meeting in Catholic Churches also have a representative of the group sitting on the parish council. About 95% of the groups also have an online presence and share information via the internet (Arnone 2016).

The Forum of LGBT+ Christians acts as an informal network of local and national LGBT+ groups, organizations of parents, and parochial groups. One of the most active hubs, which is also a point of reference for many different groups, is Progetto Gionata (the Jonathan Project), which was established in 2007 in relation to the ‘Watch against homophobia’ initiatives during the International Day against Homophobia and Transphobia. As a volunteer association gathering different Christian denominations, Progetto Gionata aims to raise awareness and discussion around homosexuality and Christianity, collecting individual life stories, informing participants about pastoral experiences, and connecting homosexual Christian groups.

The networked Christian LGBT+ community has relationships with international groups, LGBT+ organizations, and LGBT+ religious organizations. In 2015, the first Assembly of the Global Network of Rainbow Catholics took place in Rome during the opening weekend of the second Synod on the Family. However, contacts with the official Catholic Church hierarchy appear to be more complex, and the strategic guidelines of the Forum of LGBT+ Christians always include the need to strengthen connections with Christian organizations related to the Catholic Church, such as the Boy Scouts or Pax Christi. One of the most relevant issues is related to the invisibility of these groups. The ongoing project Religo, which collects pictures and life stories of Italian LGBT+ Catholics, in framing the issue, affirms the following:

The “path” includes regular meeting to discuss individual experiences, as well as the Catholic doctrine. Although the groups have different approaches, they usually encourage individuals to fully live their sexuality and affectivity. The presence of clerical figures is quite rare, as the local parishes ask the groups to be discreet. The famous 2013 interview during which Pope Francis answered, “Who am I to judge?” to a question about homosexuality triggered a process of renewed networking and organization of initiatives of visibility9. Nonetheless, both the Catholic Church’s and the Pope’s positions remain clear: Catholicism should be inclusive, but homosexuality is a disorder, as the Pope himself affirmed in another well-known interview in 201610.It is indeed visibility the main problem of the prayer groups. The reactions are still tepid and often conditioned by the request of invisibility by some dioceses. The process for creating a local group involves two steps: first, the request of meeting rooms to the local parishes, second, an official request to the Bishop for starting a path of support for LGBT persons.

Along with visibility, the other most relevant issue is their relationship with the Catholic Church. Despite occasional individual initiatives of local clergy, the hierarchy defends the official position and often intervenes by suspending or excommunicating unaligned priests. Only in some cities is there a pastoral care for homosexuals. Mostly, the Catholic Church actively adopts a silencing approach of invisibilization.

The digital environment is an important forum for discussing faith and homosexuality, in addition to being a place to meet other community members. While the public Facebook pages and Twitter profiles are characterized by low levels of interactions, discussions unfold in closed groups and online communities, in which participants construct their identity as LGBT+ Catholics, discuss their marginalized position in the Churches’ communities, and negotiate a shared culture.

5.1. The Multifaceted Forms of Religious Authority: Roles

Considering the figures of authority (the category of “roles”) mentioned in the aforementioned online discussions of the study group, God was the most referenced in a positive light, which is consistent with Campbell’s findings on Christian bloggers (Campbell 2010).

However, if we consider the roles category more generally (see Table 1), references to “popes” were the most frequent (27.21%). The current Catholic Pope Francis emerged as a crucial point of reference, who raised the hopes of the group toward internal change, especially with respect to the recognition of homosexuality. After the initial excitement, however, disillusionment prevailed. He was criticized for his ambiguity on the topic of homosexuality and for his position on the so-called gender theory, as the following message (2015) shows: “At first, I had huge expectations on Francis. Now, after he got stuck on the gender issue, I’m extremely disappointed”. However, he remained an overall positive figure in the discussions. “His ‘Who am I to judge?’ [comment] was really incredible, after years of silence, of blame”, commented one member. The overarching narrative in the group considered Pope Francis to be a potential factor of change, kept hostage by the Catholic Church hierarchy, which severely limits his actions (see also Marzano 2018). He was often compared to previous Popes, among whom only Paul VI and John XXIII were positive figures. Benedict XVI was widely criticized, whereas the figure of John Paul II was more controversial. Moreover, a small percentage (3.42%) of comments made a general reference to “the Pope” without specifying a particular person, such as in The Popes do not have this or that power.

Table 1.

Religious authority—roles.

Local priests were often referenced in the debates within the community as members confronted their experiences. Priests’ authority emerged as locally rooted and mainly related to the liturgy and the sacraments, for example, giving or not the absolution after confession (in the Sacrament of Reconciliation). A message discussing the Synod on Youth in 2018 stated the following: “[Name], I confessed to my sins one year ago, and said I had been with a girl. The priest told me that I must embrace my cross and live in chastity. I left the Church sad”. Other priests provided different answers. For example, in the experience of another member (2017), the local priest offered the absolution:

“He leads the parishes since about three years, I know him quite well. I told him about my partner since the first confession with him. Of course, although gently, he always tried to dissuade me, underlining that God’s plan for me was probably other and that I should have listed to him in my hearth, and understand that my choice wasn’t right. However, he always granted me the absolution, even though I never included my homosexuality among the sins”.

Catholic priests embody everyday religious authority, and in the community debates they are considered extremely relevant actors: priests’ decisions and attitudes can indeed result in the inclusion or exclusion from God’s grace11 and the Catholic community. In relation to this, in the community, a debate developed about the choice between looking specifically for a friendly priest, adjusting to the local parishes, or ignoring the priests and favoring a direct relationship with God. This latter choice sparked discussion about the ground upon which religious identity is constructed: on the one hand, critics underlined that religious identity cannot be grounded on selectively adopting theology or liturgy; on the other, supporters referred to the fundamental roots of Christianity. One member, for example, said to be inspired by “[t]he fathers of the Church, who practiced a more essential Christianity”.

The authority attributed to the Bishops is different: bishops and cardinals embody the Catholic theology rather than the liturgy. In this sense, their actions and speeches were reported and analyzed in order to understand whether or not changes were occurring in the Church. Some bishops were considered friendlier than others: Cardinal Marx, for example, the current president of the German Episcopal Conference, was quoted in relation to his welcoming and innovative attitude toward LGBT+ Christians. The American Jesuit priest and writer James Martin also received attention as the author of Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity (Martin 2017). Other important figures were LGBT+ friendly theologians. These theologians, together with other concrete allies (such as a psychologist who always participates in LGBT+ Christian national meetings or the Bible scholar Alberto Maggi), compose a constellation of—mostly religious—authorities of reference. Furthermore, the discussions singled out specific names and roles to define the community boundaries. Journalist and blogger Costanza Miriano, well known for her hostile position with respect to same-sex partnership, was, for example, named as an example of an “untrue Christian”.

Broadly speaking, however, female figures were significantly absent from the discussion (except for the Virgin Mary, 0.42%). Saints were referenced on different occasions. Saint Paul was quite present in the comments (1.81%) and often depicted in negative terms due to his position and writings about homosexuality. Among the different authority figures, community members named traditional religious authorities (e.g., the current Pope, God, Jesus) and specific people (e.g., Cardinal Marx, Cardinal Tempesta, the Jesuit James Martin, the Bible scholar Maggi) who contributed to defining the group culture and identity, as well as its boundaries.

5.2. The Multifaceted Forms of Religious Authority: Structure

With respect to structure, the Catholic Church, in terms of both community (or People of God) and hierarchical organization, was the authority most called into question in the online discussion. The Catholic Church was said to exclude LGBT+ people, with a few locally rooted exceptions. Moreover, it was considered to be discriminatory and incapable of change. In this sense, the Catholic Church and its internal structures (the local parishes, the hierarchy) frustrated the desire to belong. Examples of sentences referring to the Catholic Church’s structure included the following constructions: “The Church says” or “Despite what the Church says”. The reference to Roman Catholicism was often implicit.

There was an emergent tension around the issue of “belonging” and a complex negotiation over the meanings of “church” and “Catholic community”. One position in the debate advocated reclaiming rightful belonging, which derives from the sacraments (Baptism, especially) and from the love of God. Hence, belonging does not need to be positively acknowledged by the Church structure, because it is a fact: LGBT+ people belong to the universal Church of People of God, and they find their community in the network of LGBT+ groups. In this sense, they criticized the Catholic Church.

A second position considered instead the importance of the Catholic Church’s transformations and praised these changes. For example, one message in the community (2014) stated that “it is important to see the good everywhere.… We must rejoice in this Church—semper reformanda—day after day it tries progressing in the Love toward God and the neighbors”.

A third position focused instead on the relevance of an explicit recognition. This relevance rests on the collective and hierarchical character of Catholicism: without public recognition, there is no full participation. According to this view, LGBT+ Catholics bear the collective responsibility of demanding internal change. Furthermore, this position shared the opinion that the Catholic doctrine is not flexible and cannot be selectively chosen, which raised the issue of whether those who condemn LGBT+ people can call themselves Catholics.

In relation to this topic, the authority role of the liturgy was also called into question. The main issue concerns the role of the liturgy and the sacraments in defining inclusion in and exclusion from the Catholic Church structure. Baptism, the Eucharist, attending mass, and participation in general were discussed with respect to their function within Catholicism. Moreover, as already mentioned, it was discussed whether specific sacraments (such as Reconciliation) are necessary in order to be part of the Church community: if Reconciliation is necessary to receive the Eucharist and if homosexuality is a sin to be confessed, what happen if the priest does not grant the absolution? Is it grounds for exclusion from the community?

One message in the community particularly exemplified the entanglements between the Catholic Church structure, the liturgy and the sacraments, and individual religiosity: “Personally, I have no relationships with the hierarchical Church, except when I need a sacrament. I know some may disagree”. In the message, the “hierarchical Church” referred to the Catholic Church’s traditional and official structure as opposed to the informal structure composed of friendly groups and inclusive communities.

LGBT+ Christian groups provide an important point of reference for the elaboration of arguments on religion and homosexuality and constitute the “Church community” that the traditional structure does not offer. Moreover, on- and offline communities of LGBT+ Christians are points of reference for coping with the deficiencies of the Catholic Church. Such groups are also an important source of expertise for dealing with family (parents or relatives). As a structure, family was compared with the Catholic Church in terms of teachings concerning homosexuality as well as potential exclusion.

As shown in Table 2, other Christian religions (8.49%) were also called into question, especially with respect to their positions on homosexuality, in comparison with the Catholic Church. Among them, the Waldensian Church (2.06%) was referred to as the opposite of the Catholic Church: modern and inclusive. Since 2015, the Union of the Methodist and Waldensian Churches has blessed same-sex couples, and broadly speaking, it holds quite liberal positions concerning ethical issues. Despite the sympathy that the Waldensian and Methodist Churches raise, conversions in the community were barely mentioned. As this 2015 message explained, “I want to walk among the People of God […] It would be easy for me leaving the Catholic Church to one Protestant Church able to welcome me as homosexual person; but I prefer to be the Witness of the Love of God in the Church in which He placed me”. Together with the demonstrated levels of expertise on religious texts, these data were not surprising, considering that those who chose to participate in the LGBT+ groups and the digital community were moved by the profound unease they felt with the Catholic Church, which was related to their intense religiosity (otherwise, the issue would not have been a matter of discussion). Other religions were seldom mentioned (1.40%). Islam’s position on homosexuality earned some attention (1.20%), but the main focus was on Roman Catholicism.

Table 2.

Religious authority—structure.

There was also quite a lot of attention paid to specific Catholic Church structures and internal actors. The Synods were under observation—especially in recent years, since the Italian government approved same-sex civil union (2016). The Synod on the Family was expected to open space for dialogue. The Jesuits were also quite often cited (3.01%), mainly in a positive light: their position and practices offer a point of reference from which to discuss homosexuality in the Catholic Church. The same attention was paid to non-Italian Episcopal Conferences, whose attitudes toward the inclusion of LGBT+ people and issues were analyzed and often praised.

Religious movements internal to the Catholic Church (such as the Neocathecumenal Way or Communion and Liberation) were mentioned to underline their strict doctrine against homosexuality and were identified as extremely problematic. Some comments (1.46%) in the group mentioning conversion therapy also emerged. They argued that an opening from the Catholic Church to discuss homosexuality would not be enough as long as conversion groups are given the freedom to advance their positions. Finally, some reference was made to the Ecumene (2.76%) from the perspective of moving beyond the differences among the Christian Churches.

5.3. The Multifaceted Forms of Religious Authority: Theology and Texts

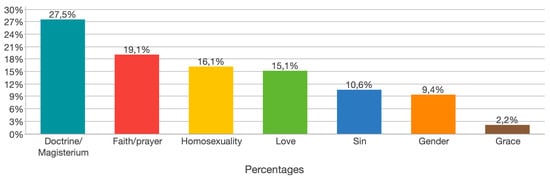

The discussions around theology included issues relating to the authority of the Catholic doctrine and specific concepts and beliefs, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Religious authority—Theology.

Among the different elements of religious theology, the Catholic doctrine and magisterium were often called into question (27.5%). In the forum, what the “doctrine says” was depicted as being inescapable. In discussing the documents issued by the Synods on the Family in 2014 and 2015, one message (2016) noted the following:

In relation to this opinion, discussions were sparked on the doctrine related to homosexuality and sin, with the community members analyzing the exact meanings and roles of these concepts within Catholic theology.[A]ll the documents speak about pastoral care of LGBT+ people (or parents of LGBT+ people), and not about the doctrine. Hence, they share the assumption that LGBT+ people are in sin. As a consequence, we consider that, as long as the doctrine stays the same, there could be no inclusion of LGBT+ persons.

The theology of God’s love, charity, and compassion held an important role among the authority references in the debate, contesting Catholic theology on sin and homosexuality. The tenets of love and Jesus’ fundamental commandment of love12 also featured in many arguments (15.1%), articulating the primacy of the messages advanced in the Gospel over those in the Old Testament. In this sense, issues of theology and texts were entangled, and the authority arguments reinforced one another. Citing the words of the most-cited Bible scholar to answer the doubts of another member, one message (2015) stated the following:

We should not look in these texts for something that wasn’t there at the time. The huge strength that Jesus gave to the Gospel is when he says “The spirit will guide you on the future issues”. The community gas the capacity, thanks to the Holy Spirit, to give new answer to new needs.

God’s grace was evoked in broader terms. Rather than in specific arguments, grace was mentioned when dealing with complex family situations or individual experiences: the grace of God holds the power of hope and salvation. From this perspective, it played a role similar to that played by faith and prayer. Often mentioned (19.1%), solid faith and constant prayer were the most liturgical elements of Catholic theology emerging in the community discussions. Even though, following Campbell (2010), they were categorized among the elements of theology, in this community, faith and prayer were mostly framed as ritual practices.

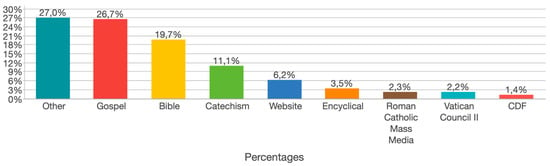

The community also paid attention to the debate over so-called “gender theory” (9.4%). Even if this issue is not directly related to homosexuality, community members feared that it would have a negative effect on their situation. Moreover, they criticized Pope Francis’ position on gender theory, which seems to reflect the stereotypes of the more traditional Catholic Church structure. Moreover, they cited many different—non-religious—sources that explain the Catholic Church’s misreading of the issue. Non-religious texts were indeed quite often discussed and referred to in the community discussions, as shown in Figure 2 (27%).

Figure 2.

Religious authority—texts.

The Gospel was often quoted (26.7%) as a source of emotional religious stories, an affirmation of God’s love, and a testimony to Jesus’s “scandalous behavior”. The Gospel was used to argue that obedience is not a virtue, that Jesus praised the marginalized sectors of society, and that his message was revolutionary. Hence, the Church structure risks suffocating the change and the experience of a thriving lived religion to respect an old and rigid tradition: “Jesus took stances in favor of the creative God, against the legislators and his representatives”. Another member invited the community to “return to the beauty and freshness of the gospel, without all the scaffoldings erected by the Church”.

Separate from the Gospel, the Bible category referred to all the other mentions of the sacred scripture, such as the discussions around Leviticus, which contains the condemnation of homosexuality. Broadly speaking, the community members reinterpreted the oldest parts of the Bible in light of the messages of the Gospel. In debating the sacred scripture’s positions on homosexuality, one member stated that “[i]f we believe that within the Bible, the Gospel holds a privileged position for the Christians … We must recognize that the Gospel never explicitly condemned homosexuality … Once the Biblical-exegetical obstacle is overcome…”. Another member answered, observing that “[t]he biblical obstacle has already been overcome. A correct exegesis indeed removes all doubts about the Leviticus and Saint Paul”. The discussions, revolving around the specific phrasing of sentences, show the members’ detailed knowledge of the sacred texts.

Among the religious texts, the Catechism and the documents issued by the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith (CDF) embody the Catholic doctrine. These documents were mentioned in relation to how they shape the doctrine on homosexuality. The Catechism’s reference to “intrinsically disordered acts” was the object of wide criticism, as may be expected. Other relevant texts were those proposed by the LGBT+ Christian groups, Encyclicals, Vatican Council II, and news and discussions reported by the Catholic mass media sphere (including l’Avvenire and Famiglia Cristiana).

The discussion around one of the first documents that the Italian LGBT+ Christians organization drafted was particularly animated; it was drafted under the suggestion of the European Forum of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Christian Groups. The document was to be delivered to the Catholic Synod taking place in October 2014. The draft document included a request for acceptance and inclusion of LGBT+ persons; support for their desires for family, marriage, and parenting rights; support for the rejection of reparative approaches; support for the fight against homophobia; and a commitment to pay attention to the training of educators. During the debates, messages conveyed simultaneously the hope for change and a sense of disillusionment. One member, for example, stated the following:

I know it is huge, but what if we ask to revise, at least in the wording, points 2357/8/9 of the Catholic Church Catechism? … As long as the vision stays the one expressed in those few lines, the Pope could say positive things but we will never solve the problem of homophobic (self-declared) Catholics.

This discussion sheds light on the complex contradictions characterizing the LGBT+ Christian community, including the desire to belong, the feeling of marginalization, and the sense of hopelessness with respect to any possible internal change.

6. Mediatized Religion and Unheard Religious Voices—A Discussion

In this paper, I focused on one Christian LGBT+ digital community in Italy to explore how its members discursively engage with the official religious authority of the Catholic Church. Following Campbell (2010), I unpacked the concept of religious authority in roles, structures, theology, and texts. I focused on the LGBT+ community, whose belonging in the official religious structure is still a matter of debate.

The research constitutes one of the few studies on unofficial Catholic digital communities, providing information on an underexplored topic. The case selection followed the logic of exemplarity: the digital community was chosen as representative of similar digital environments. Similarly, the selected sample of discussion provides information and data about the engagement of unofficial Catholic digital communities with respect to religious authority.

Among religious figures of authority (roles), in addition to God, the community praised Pope Francis, as well as certain Cardinals and Bishops who express openness to the recognition of LGBT+ Catholics and theologians proposing alternative readings of the Bible. In relation to structure, there emerged a distinction between the Church as a community of the faithful and the Catholic Church’s traditional hierarchy, whose role was challenged. The main issue concerned the open recognition of the existence of LGBT+ Catholic groups, for which relationships with the official Church structure would be crucial. Instead, to the community members, the Catholic Church structure seemed incapable of including its peripheries. Other structures were praised by the community members—particularly, the LGBT+ network, which provides for an alternative Church or community space. In terms of theology, love and faith held important positions in the online discussion. The traditional attitude toward homosexuality was challenged: more than a radical doctrinal change, what emerged was the profound need for inclusion, recognition of rightful belonging, and open discussion. Among the most quoted texts, the Gospel held a prominent role, together with alternative and contemporary theologies and some of the documents issued by the Catholic Church, such as the preparatory and final documents of the Synod on Youth. In the community, there also emerged a profound criticism of the Catechism, which condemns homosexuality. Contrary to what Campbell found among the bloggers, the community members criticized the Bible, reinterpreting its teachings in light of the Gospel. The LGBT+ community then challenged aspects of both the structure and the theology of the current official religious authority and demanded to be included in the general Church community. In the forum, the discussions over religious authority contributed to building a Christian LGBT+ community identity and group culture, as well as shaping its boundaries.

In relation to the theory of mediatization, this case study suggests that, in Italy, traditional and official religious authorities remain the primary source of information about Catholicism. Even though representations of religions provided by popular media and expressed in digital environments are important sources for everyday understandings and interpretations of religion, in the digital forum, the arguments mobilized detailed religious knowledge grounded in religious texts and theology. Decline in church attendance, the tabloidization of mass media, and the spread of social media did not significantly erode the role of official religious sources of information and knowledge. As a consequence, the information and stories about religion produced by some of the media platforms were commented on and criticized by the forum users. The digital environment provided religion-like experiences, as suggested by the theory of mediatization; however, rather than substituting for traditional religious experiences, it provided a complementary experience.

This study also offered useful insights into how mediatization impacted the role of official religion as a medium. First of all, the digital media environment offered an alternative platform for marginalized voices, challenging the role of traditional mediators. Second, the members of the digital community also challenged the idea of mediation: in the absence of inclusive mediators, they praised direct and individual relationships with the divine, in line with the hypothesis of an emerging “post neo-protestant” faith. However, at the same time, the role of the mediators was also reaffirmed: the community members’ individualization of religiosity was not a choice—rather, it was the result of exclusion from the Catholic Church. In line with Kołodziejska’s (2018) and Campbell’s (2007, 2010) findings, religious communities are sources of advice and support, whose members mobilize religious knowledge. The criticisms that the members expressed toward the traditional religious authorities—in their different forms—were meant to be “from the inside”: Christian LGBT+ persons did not want to leave the Catholic Church (with some exceptions). In line with Neumaier’s (2015) findings, the online community offered a safe space for coping with the perceived deficiencies of the offline religious community. Rather than serving as an alternative, the online community was a supplement—a space for the re-plausibilization of religion and for re-embedding oneself in the religious community (see also Kołodziejska and Neumaier 2016).

In line with the theory of mediatization, community information on religion came from a variety of sources. Non-Catholic Christian Churches were sometimes identified as reliable sources of alternative visions of homosexuality in Christianity, for example. Moreover, the digital platform offered an opportunity for visibility and networking to minority groups. The availability of information on and symbolic resources relating to religions and the digital platform allowed the community members to propose alternative interpretations of the Catholic doctrine or the compatibility between homosexuality and Catholicism. Finally, the digital LGBT+ forum offered to its members an alternative community in which specific religious authorities were negotiated, challenged, and affirmed. In terms of legitimacy, in the LGBT+ community the traditional authority was profoundly challenged. Instead, members referred to the authority of charisma and the Church as a community, to which they all belong.

The shared group culture coalesced around a variety of elements, authorities, and points of reference. Religious authority was challenged as well as reaffirmed. This was related to the specific character of the community—composed of marginalized voices—and to the type of community—an LGBT+ group. In other words, the type of community played a role in the impact of mediatization. Moreover, the challenges to and reaffirmation of religious authority were connected to the changes in the religious practices in contemporary societies. As research shows (Garelli 2014), Italian Catholicism is practiced by a minority of the population who is particularly attentive to the orthodoxy and the orthopraxis. From this perspective, the community expressed the fine balance between a largely unchosen autonomy and adherence to the Gospel and God’s teachings. In the discussion, it was constantly emphasized that religion is not a matter of choosing the aspects that best suit you. In this sense, LGBT+ Catholics participating in the debates and engaging with the community were not an expression of “believing without belonging” (Davie 2007) nor “belonging without believing” (Berzano 2009). On the contrary, religious authority—in its different forms—was crucial for them, and they tried to bring their voices to the Catholic Church’s internal forums. However, their voices remained unheard and almost invisible. The analysis highlights the complex balance between challenging and reaffirming traditional religious authority, contributing to the research on the effects of the mediatization of religion and showing that the mediatization of religion may also have the effect of influencing the traditional religious power structures.

The LGBT+ online community is mostly unofficial—it is connected to an organized network of groups all over Italy, and it collects the voices of the networked community members, but it is not officially connected to the Catholic Church. On the contrary, this connection is precisely what the group seeks. Despite the many documents presented during official Synods and the official requests to local dioceses, the official Catholic Church structure remains mostly silent on this issue: it does not answer the contact requests, and allegedly, it informally advises the hierarchy to keep a low profile with respect to this topic and community. The mainstream attitude toward homosexuality in the Church continues to be silence and invisibilization. As a matter of fact, however, something is changing in this respect. More specifically, the words used to describe homosexuality are changing, and the topic is becoming increasingly visible. Indeed, Pope Francis was the first pope to use the word “gay” in 2013. However, silence continues to be the dominant communication strategy with respect to this issue. In this sense, even though the digital environment provides the community a space for discussion and organization, it is not enough to actually pose a challenge to the mainstream religious authority. It could be however an opportunity for further visibility outside the Catholic Church—the connections of the group with non-Catholic religious LGBT+ groups and the on-going Religo photograph project are two such examples. Looking from the perspective of the peripheries can offer useful insights into what is changing—and what is not.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers, the guest editor David Herbert, and the staff of Religions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Amiraux, Valérie. 2016. Visibility, transparency and gossip: How did the religion of some (Muslims) become the public concern of others? Critical Research on Religion 4: 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, Giuliana. 2016. Rapporto 2016 sui cristiani LGBT in Italia. Progetto Gionata. Available online: https://www.gionata.org/rapporto-2016-sui-cristiani-lgbt-in-italia-2/ (accessed on 1 August 2019).

- Aune, Kristin, Sharma Sonya, and Vincett Giselle, eds. 2008. Women and Religion in the West: Challenging Secularization. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Eileen. 2005. Crossing the boundary: New challenges to religious authority and control as a consequence of access to the Internet. In Religion and Cyberspace. Edited by Morten Hojsgaard and Margit Warburg. London: Routledge, pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bertuzzi, Niccolò. 2017. Sessualità e stampa cattolica in Italia. Un confronto fra aree e riviste. Religioni & Società 88: 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Berzano, Luigi. 2009. Spirituality as a new lifestyles. In Conversion in the Age of Pluralism. Edited by Giuseppe Giordan. Leiden: Brill, pp. 213–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bolzonar, Fabio. 2016. A Christian democratization of politics? The new influence of Catholicism on Italian politics since the demise of the Democrazia Cristiana. Journal of Modern Italian Studies 21: 445–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutros, Alexandra. 2011. Gods on the move: The mediatisation of Vodou. Culture and Religion 12: 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratosin, Stefan. 2016. La médialisation du religieux dans la théorie du post néo-protestantisme. Social Compass 63: 405–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratosin, Stefan. 2019. Mediatization, post neo-Protestant spirit and affective capitalism. In Between What We Say and What We Think: Where Is Mediatization. Edited by Jairo Ferreira, José Luiz Braga, Pedro Gilberto Gomes, Antônio Fausto Neto and Ana Paula da Rosa. Santa Maria: FACOS-UFSM, pp. 181–208. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2007. Who’s got the power? Religious authority and the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 1043–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2010. Religious authority and the blogosphere. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 15: 251–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi, ed. 2012a. Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2012b. How religious communities negotiate new media religiously. In Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture: Perspectives, Practices and Futures. Edited by Pauline Hope Cheong, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren and Charles Ess. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2012c. Community. In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Heidi A. Campbell. New York: Routledge, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2017. Surveying theoretical approaches within digital religion studies. New Media & Society 19: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi, and Giulia Evolvi. 2019. Contextualizing current digital religion research on emerging technologies. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi, and Alessandra Vitullo. 2016. Assessing changes in the study of religious communities in digital religion studies. Church, Communication and Culture 1: 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi, Brian Altenhofen, Wendi Bellar, and James Cho Kyong. 2014. There’s a religious app for that! A framework for studying religious mobile applications. Mobile Media Communication 2: 154–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli Gattinara, Pietro. 2016. The Politics of Migration in Italy: Perspectives on Local and Party Competition. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarini, Luigi. 2001. Le Voci di Dio. Stampa Cattolica e Politica in Italia. Napoli: L’Ancora del Mediterraneo. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Mark. 1994. Secularization as declining religious authority. Social Forces 72: 749–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Pauline H. 2011. Religious Leaders, Mediated Authority, and Social Change. Journal of Applied Communication Research 39: 452–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Pauline H. 2012. Authority. In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Heidi A. Campbell. New York: Routledge, pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, Pauline H., Alexander Halavais, and Hazel Kwon Kyounghee. 2008. The chronicles of me: Understanding blogging as a religious practice. Journal of Media and Religion 7: 107–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Pauline H., Shirlena Huang, and Jessie P. H. Poon. 2011. Cultivating online and offline pathways to enlightenment: Religious authority in wired Buddhist organizations. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1160–80. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Lynn Schofield. 2011a. Religion and authority in a remix culture: How a late night TV host became an authority on religion. In Religion, Media, and Culture: A Reader. Edited by Gordon Lynch and Jolyon Mitchell. London: Routledge, pp. 111–21. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Lynn Schofield. 2011b. Considering religion and mediatization through a case study of J+K’s big day (The J K wedding entrance dance): A response to Stig Hjarvard. Culture and Religion 12: 167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2007. Vicarious religion: A methodological challenge. In Everyday Religion: Observing Modern Religious Lives. Edited by Nancy Tatom Ammerman. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Lorne. 2000. Researching Religion in Cyberspace. Issues and Strategies. In Religion on the Internet: Research Prospects and Promises. Edited by Jeffrey K. Hadden and Douglas E. Cowan. London: JAI Press/Elsevier Science, pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Diotallevi, Luca. 2002. Internal competition in a national religious monopoly: The Catholic effect and the Italian case. Sociology of Religion 63: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotallevi, Luca. 2016. On the current absence and future improbability of political Catholicism in Italy. Journal of Modern Italian Studies 21: 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstadt, Daniel, Larsson Göran, and Enzo Pace, eds. 2015. Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion: Religion and Internet. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. [Google Scholar]

- Fernback, Jan. 2002. Internet ritual: A case of the construction of computer-mediated neopagan religious meaning. In Practicing Religion in the Age of Media. Edited by Stewart M. Hoover and Lynn Schofield Clark. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 254–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, Pasquale. 2015. The Concept of Periphery in Pope Francis’ Discourse: A Religious Alternative to Globalization? Religions 6: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garelli, Franco. 2014. Religion Italian Style: Continuities and Changes in a Catholic Country. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Alberta. 2017. Il soggetto religioso femminile nello spazio pubblico e la questione dell’agency. Religioni e Società XXXII: 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Alberta. 2018. Religioni di Minoranza tra Europa e Laicità Locale. Milano: Mimesis. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Alberta. 2019. Religion and political parties: The case of Italy. In The Routledge Handbook of Religion and Political Parties. Edited by Jeffrey Haynes. London: Routledge, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Alberta, and Tommaso Vitale. 2017. Migrants in the public discourse, between media, policies and public opinion. In Trade Unions, Immigration and Immigrants in Europe in the 21th Century: New Contexts and Challenges in Europe. Edited by Stefania Marino, Rinus Penninx and Judith Roosblad. Northampton: ILO-Edward Edgar, pp. 66–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Pedro Gilberto. 2016. Mediatization: A concept, multiple voices. ESSACHESS—Journal for Communication Studies 9: 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Guolo, Renzo. 2000. I nuovi crociati: la Lega e l’Islam. il Mulino 5: 890–901. [Google Scholar]

- Guzek, Damian. 2015. Discovering the Digital Authority. Twitter as Reporting Tool for Papal Activities. Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 9: 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, David. 2003. Religion and Civil Society. Rethinking Public Religion in the Contemporary World. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, David. 2011. Why has religion gone public again? Towards a theory of media and religious re-publicization. In Religion, Media and Culture: A Reader. Edited by Gordon Lynch, Jolyon Mitchell and Anna Strhan. London: Routledge, pp. 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, David. 2015. Theorising religious republicisation in Europe: Religion, media and public controversy in the Netherlands and Poland, 2000–2012. In Religion, Media and Social Change. Edited by Kennet Granholm, Marcus Moberg and Sofia Sjo. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The mediatization of religion. A theory of the media as agents of religious change. Northern Lights 6: 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2011. The mediatisation of religion: Theorising religion, media and social change. Culture and Religion 12: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2013. The Mediatization of Culture and Society. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2016. Mediatization and the changing authority of religion. Media, Culture & Society 38: 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Højsgaard, Morten T., and Margit Warburg, eds. 2005. Religion and Cyberspace. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart. 2006. Religion in the Media Age. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Horsfield, Peter. 2012. A moderate diversity of books? The challenge of new media to the practice of Christian theology. In Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture: Perspectives, Practices and Futures. Edited by Pauline Hope Cheong, Peter Fischer-Nielsen, Stefan Gelfgren and Charles Ess. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 243–58. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Ping, and Shun-hing Chan. 2015. Mediatisation, Empowerment, and Sexual Inclusivity: Homosexual Protestant Activism in Contemporary China. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion: Religion and Internet. Edited by Daniel Enstadt, Göran Larsson and Enzo Pace. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, Tim. 2017. Design and the digital Bible: Persuasive technology and religious reading. Journal of Contemporary Religion 32: 205–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblauch, Hubert. 2008. Spirituality and popular religion in Europe. Social Compass 55: 140–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejska, Marta. 2016. How Catholic internet forums are changing Catholicism. The Polish experience. In Catholic Communities Online (Blanquerna Observatory Book 3). Edited by Míriam Díez Bosch, Josep Lluís Micó and Josep Maria Carbonell. Barcelona: Blanquerna School of Communication and International Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska, Marta. 2018. Online Catholic Communities: Community, Authority, and Religious Individualization. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska, Marta, and Anna Neumaier. 2016. Between individualisation and tradition: Transforming religious authority on German and Polish Christian online discussion forums. Religion 47: 228–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2008. Rethinking cyberreligion? Teens, religion and the Internet in Sweden. Nordicom Review 2: 205–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2011. Mediatisation of religion: A critical appraisal. Culture and Religion 12: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2012a. A voice of their own: Young Muslim women, blogs and religion. In Mediatization and Religion: Nordic Perspectives. Edited by Stig Hjarvard and Mia Lövheim. Gothenburg: Nordicom, pp. 129–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2012b. Identity. In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Heidi A. Campbell. New York: Routledge, pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia, ed. 2013. Media, Religion and Gender. Key Issues and New Challenges. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia, and Alf G. Linderman. 2005. Constructing religious identity on the Internet. In Religion and Cyberspace. Edited by Morten Højsgaard and Margit Warburg. New York: Routledge, pp. 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia, and Gordon Lynch. 2011. The mediatisation of religion debate: An Introduction. Culture and Religion 12: 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, Peter, and Sonia Livingstone. 2016. Is ‘mediatization’ the new paradigm for our field? A commentary on Deacon and Stanyer (2014, 2015) and Hepp, Hjarvard and Lundby (2015). Media, Culture & Society 38: 462–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Andrew P. 2015. Digital Catholicism: Internet, the Church, and the Vatican Website. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion: Religion and Internet. Edited by Daniel Enstadt, Göran Larsson and Enzo Pace. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Mandes, Sławomir. 2015. The Internet as a Challenge for Traditional Churches: The Case of the Catholic Church in Poland. In Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion: Religion and Internet. Edited by Daniel Enstadt, Göran Larsson and Enzo Pace. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, pp. 114–30. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, James. 2017. Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity. San Francisco: HarperOne. [Google Scholar]