More than 150 years before the advent of

Black Panther, a representation of Africana religions appeared in a British cartoon called

Johnny Newcome in Love in the West Indies. In this 1808 sequential art print, the religious tradition known as

obeah appeared in a story about the adventures of a hapless English plantation master in slavery-era Jamaica. In one panel, Newcome consults an “Oby man” to seduce “Mimbo Wampo”, a slave woman. We see the black conjurer, with grizzled beard, staff, and medicine pot with feathers, grave dirt, and egg shells, dispensing assurances to Newcome, who is pictured in another scene with nine offspring from his liaison with Mimbo Wampo, now the “queen” of his “harem”. The cartoon construed the spiritual tradition of

obeah as a bizarre magical practice, while describing the perils of social intercourse between blacks and whites in the New World environment. The wry commentary indicates that prior to the twentieth century, the perceived “otherness” of African-based traditions like

obeah readily translated into fodder for satire in the comics medium.

2 1. Representation from the Outside

In the United States, issues of black representation were hard fought on the battlefields of popular culture, with comics at the forefront of many of those battles. As cultural artifacts, comics reflect many of the beliefs, values, and norms of the society in which they are produced. Insofar as African American religions are also products of culture, they are evaluated by society according to the prevailing ethnocentric standards of the majority. Nevertheless, due to their subordinate status, black religions are rarely represented on their own terms in the art and literature of popular culture.

4 For example, in the heyday of comics’ rise in the early 20th century, black religions inhabited a diverse continuum that was rarely seen in popular depictions. Churches, organized sects, folk traditions passed down from slavery, political–spiritual institutions, and house temples existed side by side in African American communities throughout the United States.

5 Often categorizing black traditions in pejorative terms as imperfect cognates of white Protestant Christianity, the disdain of the dominant society for black religions was made apparent by the invention of “Voodoo” to denote black religions of Africa, the Caribbean, and their American siblings, the black folk traditions of Hoodoo and Conjure. Adopted wholesale by comics artists and writers, cultural formations of “Voodoo” worked to vilify black religions with stereotyped characters, images, and narratives. In the first half of the 20th century, comics would turn

en masse to the use of stereotypes, a practice with profoundly negative implications.

6As a “medium of extremes”, according to comics scholar Fredrik Stromberg, comics utilize stereotypes to simplify subjects in order to generate meaning, reducing physical characteristics with a visual shorthand of basic, recognizable symbols, and imagery.

7 The early, widespread stereotyping of black religions in cartoons and comics animation was accomplished by distilling certain representational elements of African American religiosity for comedic effect. For example, between 1930 and 1950, the “golden era” of cartooning in the US, black religion was mined for its entertainment value as animators created unambiguous reproductions of 19th century blackface minstrelsy and a host of profane caricatures of the most distinct qualities of black sacred life.

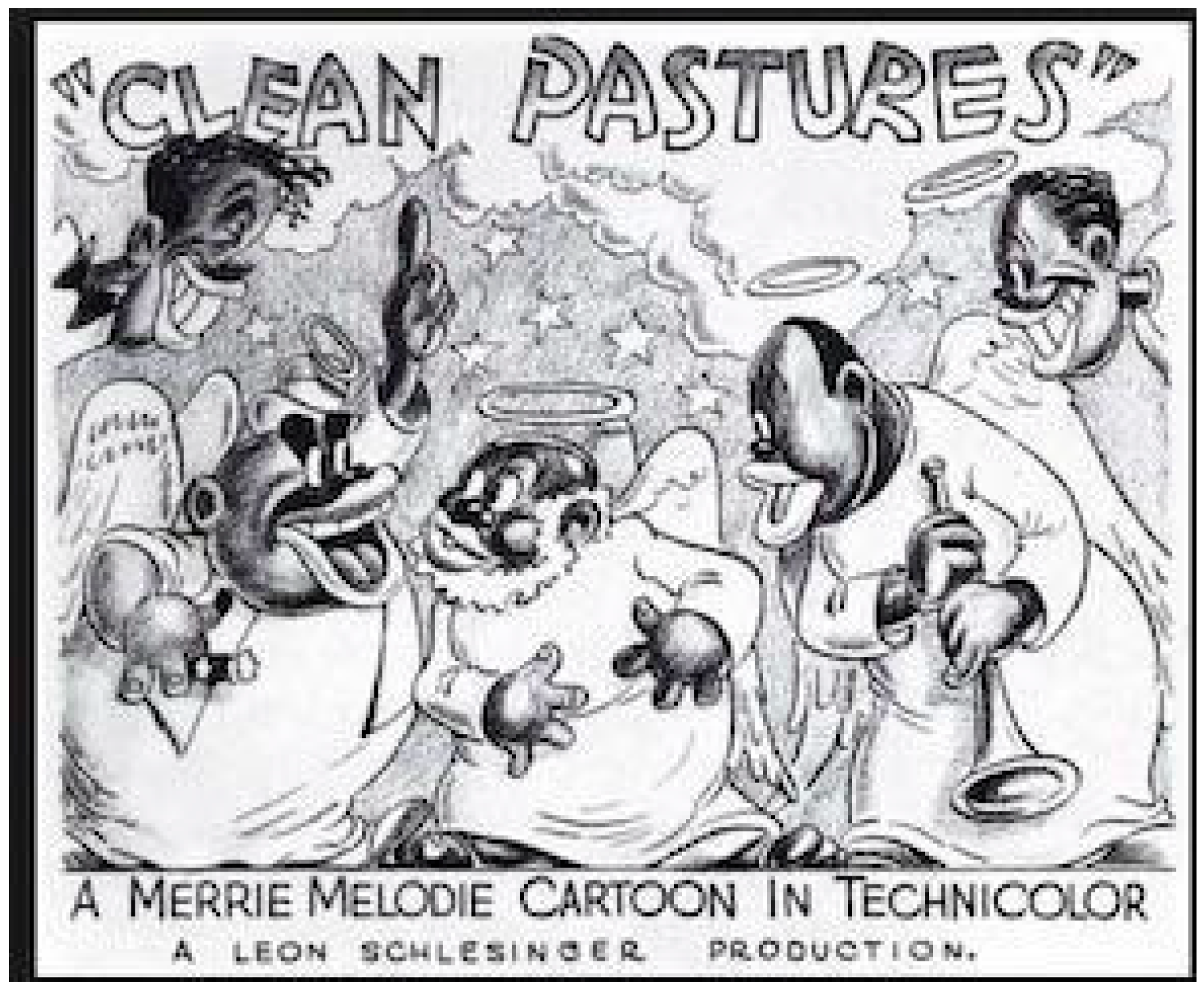

Black religious styles were consistently lampooned, as seen with the biblical satire

Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule (1934), the Merrie Melodies animated parody

Clean Pastures (1937) (

Figure 2) and the Walter Lantz supernatural ghost comedy

A Haunting we Will Go (1939), as well as Lantz’s jazz-inflected

Voodoo in Harlem (1938) and Hanna-Barbera’s

Swing Social (1940), a cartoon musical whose rendering of black religion pitted the black church against the temptations of the “Voodoo devil” in a contest with a jitterbug choir and African-styled tom-toms. Black faith was also featured in cartoons that both imitated and ridiculed its expressions, such as the propensity for unrestrained emotionalism in worship, rhythmic music, and collective ritual practices for manifesting the Spirit with physical embodiment. Despite the institution of a production code for filmmakers in 1930 that prohibited “blasphemy, religious offense, and the ridicule of clergy”, black preachers and religious authorities were regularly “burlesqued” according to cartoon historian Henry T. Sampson, while “priests, rabbis, or leaders of any other religious groups” were not.

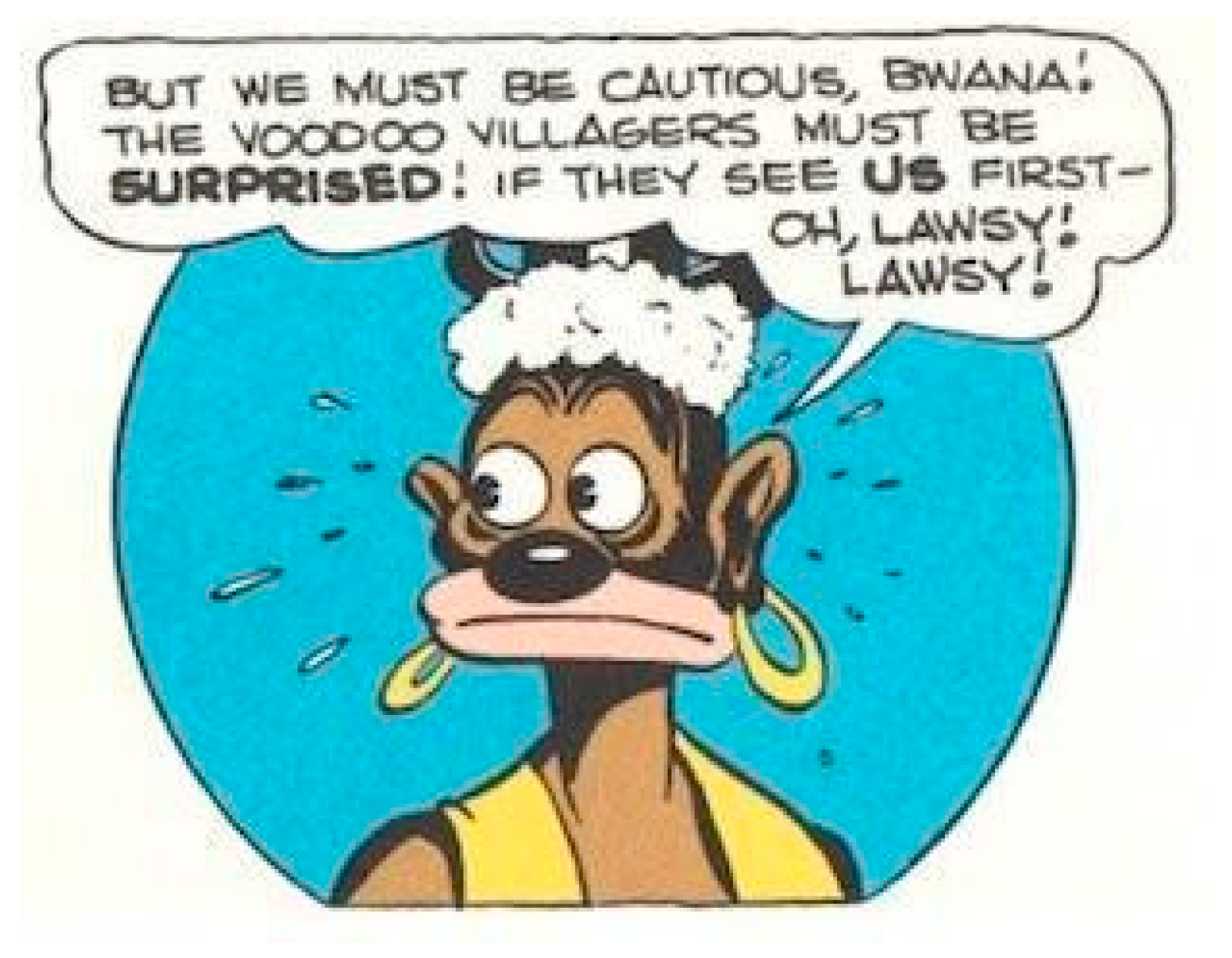

8Animation creators utilized racial hyperbole in depicting black religious practices and beliefs. For example, animated comics with traditional African American worship practices tended toward the egregious use of “Negro” dialect, frenzied dancing and singing routines, pedantic storylines, indistinguishable subhuman characters, and the creation of “moral cartoons” which blended minstrel styles and religious lessons with clownish sermonizing. Derogatory representations also extended to print “funnies” in the 1930s and 1940s, with cartoon comics like

Lil Eight Ball and Carl Bark’s

Donald Duck Hoodoo Voodoo, which maligned black spirituality as retrograde superstition, replete with blackface coons and pickaninnies whose terrified antics and exaggerated fears of ghosts provided the point for sight gags. (

Figure 3) Viewed through the lens of American popular culture in the early 20th century, comics were indelibly linked to appropriations of black religion in a pernicious cycle of love and theft—or what Christopher Lehman calls “ignorance and contempt”, as cherished traditions were subject to mockery and human characters depicted as ugly and disfigured, even as they were sensationalized as crowd-pleasing sources of entertainment.

9Proceeding from post-Emancipation black cultures in the South, the folk religions associated with the poor and illiterate classes of rural African Americans were perceived as theologically undeveloped and backward by their urban and Northern peers. However, predominantly white comics artists and animators viewed folk traditions as “authentic” black religiosity and normalized their display as spectacle. Accordingly, black churches advanced a politics of respectability and racial progress that scorned negative associations between their faith practices and what they considered to be primitive spirituality. While black churches criticized unseemly aspects of black folk religion as ignorant heathenism, they also protested the commodification of African American sacred cultures, joining black leaders and the black press in condemning the use of racial stereotypes in comics, cartoons, and animation. They were divided, however, over the social problem of controversial Hoodoo and Conjure folk practices, magic traditions which were associated with “Africanisms” and iterations of what was commonly called Voodoo.

10Pluralism and heterogeneity were defining traits of black religion in the US from its very beginnings, and spiritual diversity remains an accepted part of the culture, historically strengthening the racial solidarity and inclusiveness of black communities. However, prior to the 1960s, Africana or black diaspora religions such as

obeah,

Santeria, and

Vodou were viewed by most Americans as exotic and strange, with foreign gods, foreign practices, hailing from foreign places. Negative perceptions of these Africana traditions entered into portrayals of black religions in the comics at an early point. I use the phrase

graphic Voodoo to refer to the ongoing characterization of Africana religions as insurgent and racialized, overdetermined by associations with sorcery, and presumed to be violent and dangerous. It is important to underscore that these discursive formations were inventions, wholesale fabrications, with little to do with actual religions and historical practices. Graphic Voodoo became a signifier for spiritual alterity that marked black “otherness” with resonant elements that disfigured two historical religious sources: indigenous African sacred traditions and Haitian

Vodou. As a metonym for Africana religions, graphic Voodoo became a stand-in for race and religion as presented in many widely circulating comic books in the US, especially those of the action-adventure and horror genres.

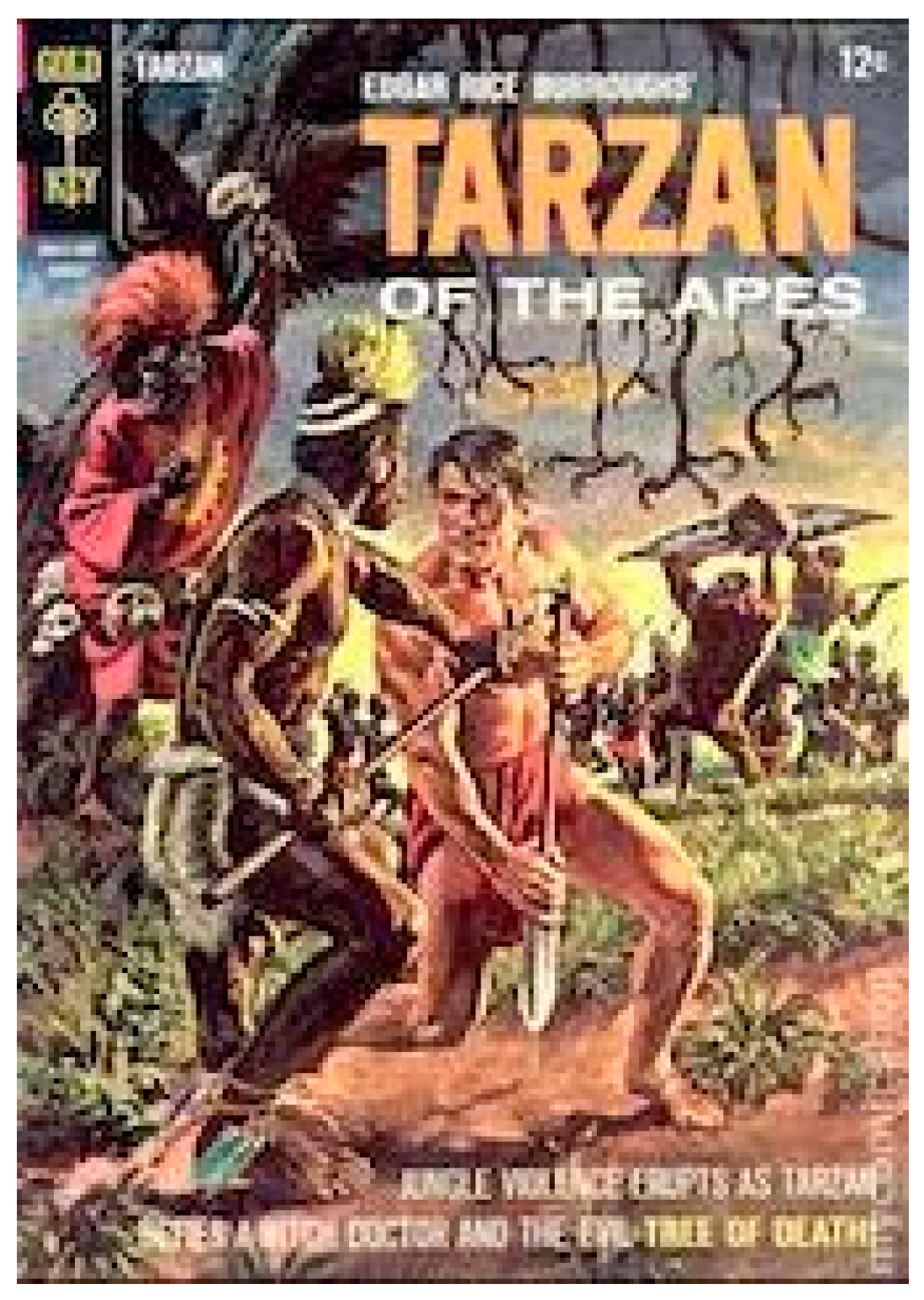

11The aesthetics of graphic Voodoo, as first established in action-adventure jungle comics, depicted Africana spiritualities as uncivilized and idolatrous, but strangely powerful and compelling. Outlandish pictures of black religious authorities in roles as Voodoo priests and witch doctors—half-naked, with grass skirts, feathered headdresses, ornamental necklaces, bones, and fetishes—registered the stereotype of the timeless “Native”. (

Figure 4) While 19th-century political cartoons and illustrated journals employed similar visuals in portrayals of indigenous people, Africana religions in 20th century comics were refracted through a prism of broadly pejorative tropes that belied their meaning as authentic spiritual traditions. Weighed against western standards and Anglo-Christian exceptionalism, African cultures were belittled; Africans were seen as abject denizens of the “dark continent”, degenerate, lacking moral virtue, “without God, law, religion, or commonwealth”. Defamation of African peoples in written and visual discourses would be used to rationalize the West’s role in the slave trade, colonialism, and its postulations of scientific theories of white racial superiority. These accepted images of Africa and Africans filtered into the comics. Later, as 20th century European neo-colonial incursions into Africa ensued, the US, driven by imperialist competition, expanded its interests into adventures closer to home with the 1915 invasion of Haiti. As the living repository of Africana sacred traditions in the western hemisphere, Haiti would come to play a vital role in comics’ representations of black religions.

12Depression-era newspaper strips were precursors to the anthologies and serials that transformed comics into comic books, becoming some of the most profitable print products in the US during the decades between 1938 and 1953. In comics of this period, black spirituality was still constituted as primitive, but presented as less of a laughing matter than with the earlier cartoons. Consider newspaper comics’ introduction of Africana subjects in storytelling through the lenses of colonial and imperial mythologies, such as the renowned

Tarzan strips and their competitors,

Jungle Jim and

The Phantom. As comics publishers capitalized on readers’ desires for escapist literature, they delivered stores with a more potent combination of racial and religious images in exciting and dangerous forms. Graphic Voodoo served to vitalize the explosive growth enjoyed by jungle comic book brands during the World War II and postwar periods. With patriotic messaging and wartime propaganda, these comics embellished American national identity with “whiteness” as the cultural norm, while “blackness” and “Africanness” were marginalized and diminished, along with their religious subjects. Accordingly, jungle comics adopted the emerging conventions of the comic book form, with heroes and superheroes as purveyors of justice, action sequences that engaged the essential struggle between good and evil, and tropical/forest settings that symbolized the untamed wilderness. The black Voodoo priest personified the criminal element, the dark-skinned savage whose depravity was ever confronted and subdued by muscular white protagonists with greater intelligence, physical power, and athletic prowess. (

Figure 5).

13 Although at least one African character,

Waku: Prince of the Bantu, made his debut in the post-World War II era, most jungle adventure comics headlined white heroes and heroines, with blacks fulfilling secondary parts as foes and adversaries.

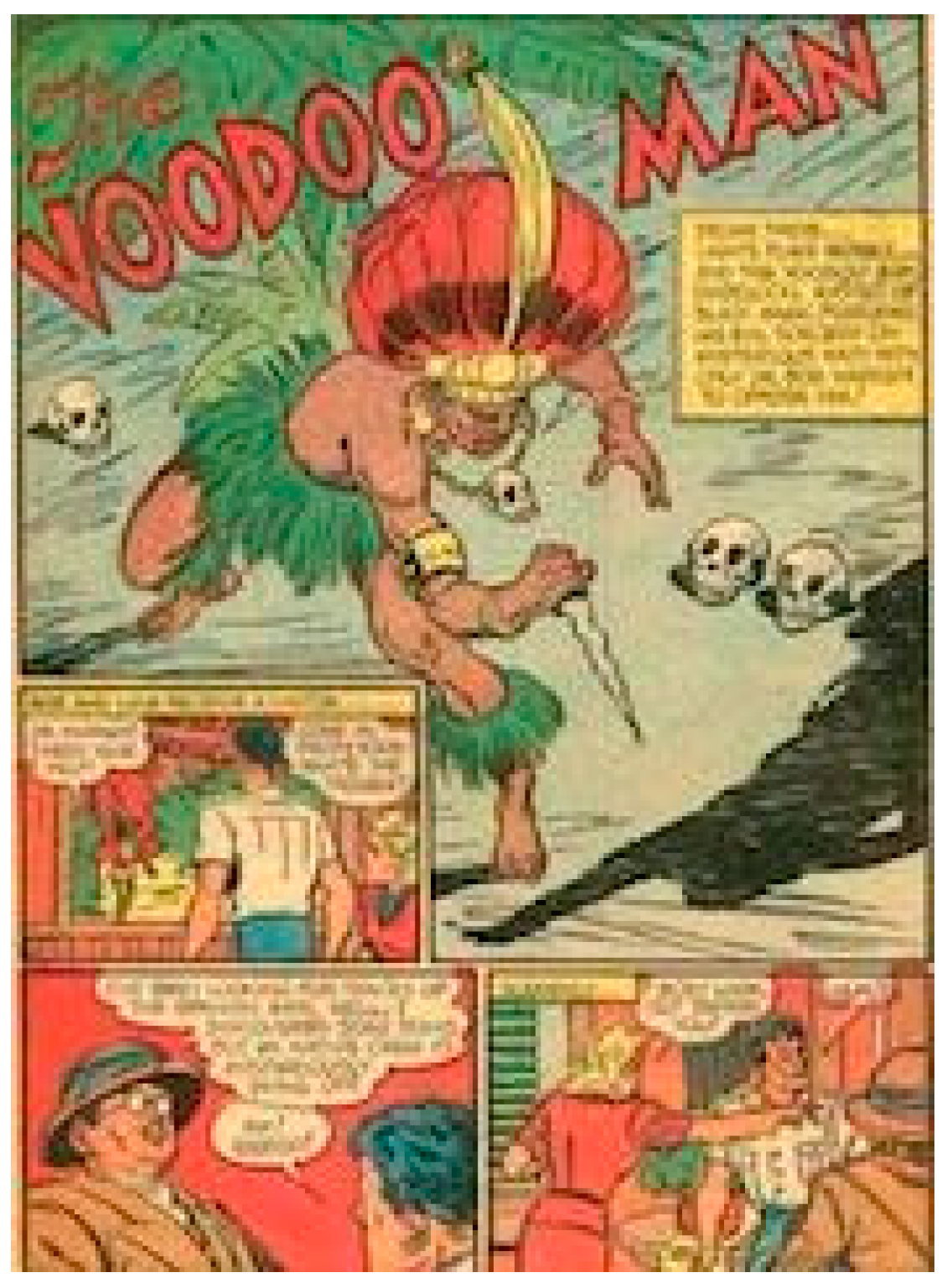

14 For instance, the Fox syndicated comic book series

Weird Comics (1940) introduced an antagonist called

The Voodoo Man, an evil mastermind whose vengeful schemes against government agents, missionary doctors, and other innocents ignited a maelstrom of deceit, fraud, and greed that compounded the collective misfortunes of his African tribesmen (

Figure 6). Although the

Voodoo Man was one of the earliest comics to feature a black character in a recurring series, Voodoo criminals were as ubiquitous as the white jungle comics kings and queens whose stories they populated. The Voodoo comics nemesis also granted implicit justification for the mollifying presence of Christianity as a civilizing force, while giving voice to a regressive political discourse of black incapacity; left to their own devices, blacks were unsuited for self-governance, requiring rescue or protection from wild beasts, natural perils, unscrupulous whites, and cynical religious frauds whose sole intent was to beguile the gullible masses with false gods and heathen idols. The Voodoo priest enacted immorality and corruption, threatened vengeance and retribution toward all who opposed him, and validated a social message of white paternalism and American-Christian virtue on behalf of the heroic jungle monarchs. For its part, graphic Voodoo provided staging for assertions of black duplicity that were articulated in episodes of some of the most widely read superhero comics in the WWII period, including

Superman,

Detective Comics,

Captain Marvel, and

Captain America.

Perhaps even more detrimental to black religions in 20th century comics was the onset of horror fiction, which transformed graphic Voodoo from a formulaic plot device into grotesque allegories of ecstatic and violent black power. Repurposing fantasies of jungle primitivism into reflexive narratives of white terror, horror comics evinced a wellspring of suspense, the perversion of good into evil, and the recasting of Africana religions as diabolical in nature. Buoyed by the success of supernatural and fantasy articles in pulp magazines of the 1920s, Voodoo horror comics drew assiduously from published reports by foreign journalists, wartime commentators, and American servicemen in Haiti during this period (

Figure 7). Men’s popular magazines such as

Weird Tales,

Strange Tales, and

Argosy refashioned the literature of the military occupation into fantastic and morbid drama for leisure readers of pulp fiction. The narratives ascribed a kind of supernatural fanaticism to devotees of Haitian

Vodou, while projecting dark impulses and delusions of race and religion onto a poor, defiant black peasant population. The 20th century US intervention in Haiti and the persecution of

Vodou evoked recollections of Haiti’s extraordinary colonial history, its claims to nationhood, and the unthinkable possibility of black rule. The Occupation highlighted in palpable terms the limits of white Christian supremacy and American sovereignty, thereby expediting the need for racial and religious fictions that referenced Haiti as the site of the West’s own lurking, hidden spiritual fears.

15Although figurations of Voodoo had circulated in books, theater, and American film since the 1930s, graphic horror Voodoo was not extensively propagated until the World War II era, when a predominantly adult male comics readership developed a taste for more explicitly violent materials. However, unlike jungle adventure comics, horror Voodoo framed Africana spirituality as the locus of malevolence, with images and stories of demonic possession, corporeal desecration, and diabolical violence. By the early 1950s, horror comic books such as

Vault of Horror (1950),

Black Magic (1950),

Mysterious Adventures (1951),

Phantom Witch Doctor (1952), and the Entertaining Comics series

Voodoo had inverted the mythos of the white jungle king into allegories of white terror and black subjugation that transmuted actual wartime atrocities and abuses by American occupying forces into unbridled aggression toward the black Other (

Figure 8). Voodoo-themed comic books also underscored Haiti’s backwardness and instability, and reconfigured religious

Vodou into graphic horror Voodoo.

16 As author John Cussans has noted, the real-life suppression of

Vodou in Haiti during the Occupation coincided with the government’s attempt to win social and political support for American ambitions on the island. “Black practices of animal sacrifice, sorcery, cannibalism, ancestor worship, divination, zombification, and possession,” he writes, “whether imagined or actual, served as a moral justification for an American civilizing mission that seemed to symbolically mark the end of the Haitian revolutionary experiment.” The Voodoo comics, with all their horrifying excesses, functioned as an archive of lurid fantasies of black supernaturalism, which served both to legitimate American interests and provide a rationale for the continued denigration of Africana religious practices and beliefs. As standard comics fare for decades to come, graphic Voodoo perpetuated many of the lingering, distorted views of Africana religions that persist in popular culture even in the present day.

17With the imposition of a self-regulatory code of content for comics publishers in 1954, the remainder of the decade saw a decline in subject matter deemed morally offensive or overly controversial, including many religious, racial, and horror-themed materials. Despite the fact that, in the first half of the 20th century, both jungle adventure and horror comics reinforced notions of black spiritual primitivism, their entertainment value in the US was unparalleled. Since the 1930s, literary and theatrical works with Voodoo themes had been marketed to American audiences, culminating in what Melissa Cooper calls the “Voodoo craze”, a cultural phenomenon in which Voodoo themes were utilized as consumable sources for news and entertainment. She notes that African American newspapers were active domains for the “mass commercialization and commodification” of Voodoo, with black journalists and black newspapers such as the

Chicago Defender, the

New York Amsterdam News, and the

Pittsburgh Courier disseminating stories of Voodoo-related criminal activity and sponsoring advertisements for Hoodoo–Conjure services in their pages. Interestingly, the circulation of sensational Voodoo subjects by American media coincided with the events of the Occupation and its brutal repression of black resistance in Haiti. Yet, as many blacks in the US looked to the founding history of Haiti as a template for African American greatness, portrayals of Africana religions colored by the racist imaginary issued forth in a variety of forms. While black newspapers were of the few arenas in which African American points of view were advanced with an eye toward supplying greater substance, balance, and nuance to their readers, they too, notes Cooper, contained “a contradictory mix of voodoo coverage” that “condemned backwardness and superstitions in the black community” while covering “sensational voodoo reports designed to entice readers.” Nevertheless, we see that it was in their emerging roles as social critics, political commentators, and humorists that African American newspaper writers and comics artists would provide new possibilities for thinking about and representing black religions in their totality.

18 2. Representation from the Inside

We now turn to representations of black religion by African American writers, artists, and other comics creators in the 20th century. By the 1930s, the combination of an emerging consumer class and the expansion of black newspapers created a demand for more relatable themes for the reading public. Artists and illustrators sought syndication for their cartoons and comics in order to bring a greater variety of perspectives to their depiction of black subjects and to counter degrading imagery that appeared in the mainstream press. Black comics in the first half of the 20th century developed in concert with the independent black press, and the historical contributions of African American editorial cartoonists to the development of the form should not be underestimated. “Black cartoonists,” writes cartoon historian Tim Jackson, committed to rebutting racist imagery of black people, and took “emphatic control of their self-image.” Here, we see the ways that African American comics artists also issued positive representations of black religiosity that counterbalanced many of the images that circulated in American popular culture. Twentieth century black newspaper cartoon and comics artists drew upon what Angela Nelson calls a “black repertoire” in their depiction of religious characters and scenarios, articulating the political, ideological, and aspirational values of their readers (

Figure 9).

19 One unusual newspaper comic in this era that centered on black religiosity and the black church was

Deacon Jones by Ike “Sam” P. Reynolds, columnist and local scribe of black Atlanta in the 1930s.

Deacon Jones was published in the

Atlanta Daily World from 1931–1932. Reynolds was well known for his reporting of local neighborhood happenings in and around the Auburn Avenue district, the thriving epicenter of black business and home to the renowned Ebenezer Baptist Church, an anchor of the African American religious community. Reynolds, who also wrote a gossip column called “Sam on the Avenue”, instilled the homiletic voice and humor of the traditional black preacher into his comic, with sketches and inside jokes from the pulpit directed at the portly Deacon, whose witty and sometimes profane commentaries appeared daily in the newspaper with a single panel gag strip, and with a longer cartoon on Sunday.

20As rare as

Deacon Jones was as a religion-themed newspaper comic strip, the appearance of black women in 20th century comics with religion topics was even more uncommon. Their absence may be attributed to the insidiousness of racialized gender stereotypes, an overemphasis on renditions of masculinity in comics, and the lengthy, troubling history of black women’s exploitation with sexually objectifying images. Nevertheless, two comics serve as bookends to other examples in this arena: first, a four-page comics feature on the life of Sojourner Truth, which appeared in a 1945 issue of

Wonder Woman called “Wonder Women of History”. The product of an intersectional collaboration between the black artist Alfonso Greene and feminist icon Alice Marble, the short graphic biography depicts the abolitionist and preacher as a devoted slave mother, evangelical convert, and ardent women’s rights advocate whose righteous dedication to her cause proved the “fighting spirit” she shared with other female subjects in the comic book series. In stark contrast, nearly 30 years later, the first syndicated newspaper strip with an African American female character in a title role debuted in the

Chicago Tribune, a romantic soap opera called

Friday Foster. The weekly comic, about the life, loves, and adventures of a single African American career girl, presented a limited story arc in which Friday, a photographer’s assistant-turned-model, squared off against a “Hoodoo Doctor” gang kingpin and cult leader in the heady urban jungle of Harlem, New York. This episode repackaged graphic Voodoo themes with 1970s blaxploitation aesthetics and other period references. The

Friday Foster newspaper comic strip enjoyed a four-year run and later took on a second life as a one-shot Dell comic book and a feature film before it was discontinued in 1975. Although these two publications present somewhat nominal portrayals of black religion, atypical as they were, their significance lies in their advancement of spaces for the future presence of black women in comics.

21Although religion remained a rock-solid institution in black American life, comics with a specific theological focus or spiritual orientation were hard to come by in the black secular press. Of course, black newspapers highlighted pertinent religious subjects, as with the signature works of the artist Ahmed Samuel Milai of the

Pittsburgh Courier (1937–1950), whose cartoons for

Your History and

Facts about the Negro occasionally juxtaposed religious themes with notable persons of achievement from the annals of African American history (

Figure 10). As comics became more deeply embedded within the fabric of American popular culture, black writers and artists over the decades strove to capture multiple dimensions of the African American experience by valorizing religious leaders and celebrities as exemplary figures and creating comic books and cartoon biographies of religiously significant personalities, such as Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali, and Malcolm X. African American religion was also presented in the comics as a catalyst for galvanizing nonviolent political activism, as seen in

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a 1956 single issue comic book by the Fellowship of Reconciliation and published by the cartoon studio of Al Capp (of

Lil Abner fame), which was distributed in schools and churches throughout the South. The 16-page comic also provided inspiration for the 2015 award-winning graphic novel trilogy by Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin,

March.

22While newspaper artists offered many meaningful contributions to the project of black representation, none treated religion more consistently than the illustrator Eugene Majied, editorial cartoonist for one of the most widely circulated African American newspaper weeklies in the 20th century,

Muhammad Speaks. Majied, who began his career as an artist at the

Chicago Defender in 1961, brought a sensibility to his work that instilled theological precepts from the Nation of Islam and foregrounded black Muslim religion in order to provide meaningful and positive self-images of African Americans. Moreover, while many of his cartoons were tempered with strong doses of racial political opinion, their subject matter dealt almost entirely with themes of religious uplift, black history, and matters of spiritual import that were infrequently addressed in secular newspaper comics. With incisive satire and penetrating analysis of current events, Majied’s cartoons reflected his strongly held convictions on the redemptive teachings of Elijah Muhammad as they related to black self-reliance, racial discrimination in the United States, and economic empowerment. His comics appeared in

Muhammad Speaks from 1960 to 1975.

23From the 1970s onward, black writers and artists harnessed the comics medium to support particular various theological agendas, to celebrate African American faith traditions, and to reinterpret traditional religious beliefs in light of a shared cultural heritage. One of the most prolific black comics illustrators from this period was the African American artist Fred Carter, whose work delivered a fundamentalist message of conservative Christian doctrine in an array of widely read pamphlets, tracts, and comic books by the Jack T. Chick Publications Company. Carter, an uncredited artist for the California-based publisher from 1975 to 1980, was known for his vivid oil-paint images which dramatized the horrors of sin, the judgment of the wicked, and the glory of spiritual conversion with distinctive graphics and lavish colors. His notable works for the Jack Chick studio included “Soul Story” and “The Sissy”, and the Christian hero-duo series “The Crusaders.” While illustrating numerous publications for the Jack Chick studio, Carter focused on creating content pertaining to African Americans and later redesigned Chick’s persuasive missionary publications using only images of black people for tracts which focused on issues such as crime, drugs, abortion, and the presence of competing religions like Islam and African diaspora traditions. A Pentecostal minister, Carter also illustrated a race-specific bible for Nia Publishing/Urban Spirit Ministries called

The Children of Color Bible, in which he reworked Old and New Testament stories into brightly rendered images of black- and brown-skinned characters with the original biblical narratives.

24In contrast with the prolific but sometimes controversial work of Jack Chick, other religious comics publishers made black representational inroads by adding storylines that were attuned to African American experiences. An example of this genre is the comic book

Up from Harlem from Spire, an imprint of the Christian publisher Fleming H. Revell (1974), a company dedicated to creating educational comics with an evangelical theological slant.

Up from Harlem is an account of the life story of the African American street-gang member turned preacher Tom Skinner, whose stirring biography was one of several titles published in Spire’s extensive series of illustrated stories about celebrity Christians, ministers, and missionaries. The comic, which adopted the unmistakable idioms of the “Soul” era, relayed a dramatic account of Skinner’s unlikely religious conversion and rescue from the social ills of poverty and inner-city gangs. Skinner, depicted in the comic as a real-life black “street prophet”, would go on to become a charismatic motivational preacher whose passionate witness and radical critique of social and racial injustice made him one of the most prominent African American Christians on the white evangelical crusade and missionary circuit in the 1970s.

Up from Harlem is one in a genre of publications that privileged the Christian viewpoint while focusing on the pathologies of urban African American culture, promoting the need for spiritual transformation among black people as a primary evangelical endeavor.

25In the final quarter of the 20th century, dedicated artists and writers adapted the modern conventions of comics storytelling in works that accorded complex characterizations of black religion in narratives of fantastic, superhuman characters and godlike heroes that spoke explicitly to themes of Africana spirituality and racial identity. With the introduction of African and African American superhero characters in mainstream comic books in the late 1960s, graphic Voodoo would be deployed once again, but now with an alternative, positive take on race and religion. A Marvel superhero by the name of

Brother Voodoo first appeared in the 1973 comics series

Strange Tales in a supporting role as a supernatural agent and protector of justice. Later, he would be featured in his own series as one of a leading generation of “black power” superheroes (

Figure 11). Brother Voodoo personified conventional styles of superhero masculinity and enacted comics horror tropes while complicating questions of racial and religious authenticity in his role as an Africana religions practitioner. This time, it was

Vodou, not Voodoo, that was reformulated as a weapon of choice in an arsenal of enhanced abilities for Jericho Drumm, a repatriated Haitian, in his secret identity as a mild-mannered and rational black psychologist. Brother Voodoo wielded a cache of superpowers loosely associated with Haitian

Vodou, including the deities known as

loa, the ritual technology of spirit possession, and the artifacts of magical protection and defense called

wanga. Although the character engaged in supernatural warfare against zombies, evil bokors, demons, and stock graphic Voodoo villains, the comic drew from an extensive lexicon of Africana cultural styles that transformed him from a mystical sorcerer with an obscure pedigree into a consummate down-to-earth action hero with a historical black diasporic religious lineage.

26The 1980s and 90s inaugurated shifts in the work of comics writers and artists of the post-civil rights, post-black power generations, and institutionalized a more diverse readership of the comics themselves. A decisive period in mainstream comics production, unstable economic trends, and the declining sales of newsstand comic books led to an increase in direct marketing and a subsequent turn by artists and writers to more mature, violent, and psychologically driven narratives. Concurrent with these trends, the establishment of independent black comics had a massive impact on the medium itself, leading to a re-envisioning of black representation, with respect to themes of race, religion, and spirituality. A signal event was the 1993 founding of Milestone Media, a publishing collective of African American artists and writers that tapped crossover markets in an appeal to diverse audiences all the while initiating conversations about racial representation went beyond the black/white binary.

27 Yet, while Milestone opened up opportunities for the presence of new black characters and themes, neither religion nor spirituality was of great significance to their conceptualizing of African American subjects. Milestone’s culminating success was their achievement of greater ethnic representation in the comics industry and the recognition of the need for black comics creators to control the licensing, distribution, and publication of their products; it fell to independent black comics publishers, drawing impetus from cultural movements such as Afrocentrism and black nationalism, to put forth relevant religious subject matter. For instance, Onli Studios, founded by Chicago-based artist Turtel Onli, as well as the Association of Black Comic Book Publishers (also known as ANIA), a consortium of four Black-owned comic companies, promoted comics that merged ancient myths, black diaspora imagery, and Afrocentric themes with conventional crime and superhero narratives. In most of these comic books, spiritual, esoteric, and mystical symbols and themes formed the center of their vision of black culture. Insofar as these contemporary writers and artists considered mythic blackness and the Sacred as dual lenses with which to create stories and images, they utilized a variety of resources, including iconographic imagery derived from Egyptian and Khemetic motifs, technologically complex tropes from science fiction, and traditional theological frameworks from indigenous African faiths. Onli, also known as the father of the “Black Age of Comics”, wrote, illustrated, and published a spectacular universe of comic book titles that employed black and Africana spiritual frameworks. Onli said that an “African American aesthetic” imbued his work with purpose and meaning as it drew inspiration from African American arts activism of the 1970s (in movements such as

BAM). His spiritual and artistic sensibilities converged in the publication of his 1981 comic

NOG,

Protector of the Pyramides, the story of a powerful entity from a race of immortal beings whose mission was revealed to be cosmic guardian of the planetary outpost Nuba (Nubia). Similar themes would be taken up by other independent black comics in the latter decades of the twentieth century, including, notably, the work of Roger Barnes, whose

Heru,

Son of Ausar (1993) brought ancient stories of the Nile Valley to life in tales of primal beings, demigods, and goddesses that waged epic battles against earthly oppressors, presenting new mythologies of powerful black heroic defenders of the righteous against corrupt invaders and alien malefactors (

Figure 12).

28By creatively adopting African-centered metaphysics and cosmologies in their world-making practices, latter twentieth century black comic writers and illustrators anticipated the black arts and culture movement known as

Afrofuturism. In emphasizing the speculative and the technological in service to Africana identity and liberation, Afrofuturism re-envisions the past in ways that reach beyond the present histories of black people in the West.

29 Comics Afrofuturism, as defined by communications scholar Reynaldo Anderson, is an aesthetic orientation that conceives of alternate realities, utopian and dystopian scenarios, and scientific archetypes in imagined narratives of the future for black people. Strongly mythic in its expressions, Afrofuturism “reinvents a visionary discourse related to the diasporic experience [that is] impacted by technological transformation,” Anderson writes, but “remains connected to an African humanistic past.”

30 Religiously inspired Afrofuturism, in various manifestations, draws from indigenous African religions, biblical prophecy, and ancient esoteric literature as resources to explore topics like time travel, astronomy, space exploration, and the integration of machine and human consciousness, centering characters and themes that speak to black resistance and liberation. By reformulating the mythic past and reconstructing the present through speculative narratives, independent black comics creators extended the very notion of “religion” beyond traditional conceptualizations and reclaimed Africana spiritual sources as central to the representation of black religions in US popular culture.

3. Conclusions

We complete this discussion having come full circle, “looking at the past to retrieve what was lost, and reclaiming the present”, as the wisdom sayings of the Akan Sankofa philosophers affirm. From early images of black religion in twentieth century comics to the present day—with the extraordinary 2018 comic book-based film Black Panther opening up new domains of Afrofuturist representation—black American religions and Africana spiritualities were transformed from a waning trajectory of negative images, stereotypes, and distortions that once dominated comics art and narrative. Even now, black and Africana spiritual themes resonate with the latest generation of comics consumers, whose relationship to race and religion appears to be far less sectarian and more religiously expansive than any that came before them. The comics of the past century offer an array of valuable lessons as we consider the treatment of black religion as subject matter in US popular culture. Comic books, cartoons, animation, and newspaper strips conveyed harmful assumptions and racist ideas in their treatment of black and Africana religions, but comics were also used as a corrective, offering truer and more authentic perspectives. This investigation of black religion and comics, while limited, shows how comics articulated understandings of blackness, race, and Africana spiritualities that both supported and contested the views of the dominant society. What conclusions may be drawn regarding the significance of black religions and their depiction in comics? Firstly, it is worth underscoring that, as the comic developed as a multi-faceted form in the twentieth century, so did the breadth of styles by which black religion was illustrated. From the early caricature and satirizing of African American church performances, black folk traditions, and Africana practices in cartoons and animation, to the contrasting presentation of religious themes as viable subject material by the black press and mainstream comic books, depictions of black religion were shaped by perceptions of their creators and their readers, even as the expansion of the comics medium would be ultimately industry-defined. The rise of Graphic Voodoo in the early twentieth century as an imaginary construction and false depiction of black religious and spiritual otherness is an example of the power of outsider representations that has had considerable cultural impact, as it was later adopted, appropriated, and disseminated both by insiders and others, becoming embedded within comics discourses even in the present day. Notwithstanding their commercialized aspects, comics centering on blackness and spirituality advanced over the decades as increasingly visible presentations of racial identity, becoming more salient in US popular culture. In response to these trends, black artists, writers, and creators in particular have developed more elaborate, complex, and authentic depictions of black religiosity and spirituality through comics storylines, characters, and images. It may be possible to consider comics as one of many forms of religious definition and expression—as facilitating new and imaginative spiritual practices of meaning-making through narrative, art, and social commentary that focus on traditional and non-traditional spiritual sources, persons, and subjects. Historically, black religious representation in comics originated as one-sided, created and offered as a spectacle to be viewed from the outside, looking in; in large part, the work of black artists and writers in the 20th century exemplified the struggle to correct and take control of the same so as to provide images and narratives with an insider’s vision. It remains to be seen in what new directions comics and black religions will flow in as they extend into the 21st century, but it is clear that, for comics creators and their readers, the future is present.