Mobilizing Shakti: Hindu Goddesses and Campaigns Against Gender-Based Violence

Abstract

:This statement addresses the complexities of the woman-as-goddess equation and argues that the status of human women, and their association with the shakti of divine females, is contextually shifting.By virtue of their common feminine nature, women are in some contexts regarded as special manifestations of the Goddess, sharing in her powers. Thus, the Goddess can perhaps be viewed as a mythic model for Hindu women. [...] Nevertheless, some feminists and scholars of religion have argued that the existence of the Hindu Goddess has not appeared outwardly to have benefitted women’s position in Indian society. The question of the relationship between Indian (primarily Hindu, but including Buddhist and Jain) goddesses and women in multifaceted and complex, frequently leading to contradictory answers, depending upon how the question is framed and who is doing the asking–and answering”.

Shandilya explains that, alongside the Sanskritic Hindu names, media narratives and chosen images continued to isolate aspects of her story that reinforced a middle class identity (her education, her light-skin), and her innocent nature.5 Shandilya critically analyzes how these narratives actually contributed to a Brahminization of Pandey’s identity, feeding into right-wing Hindu discourses about the protection of the chaste Hindu woman (Shandilya 2015). Subsequently, she argues that these representations actually result in the marginalization of Dalit women in legal and social reform (Shandilya 2015).6 As both the Abused Goddesses and the Priya’s Shakti campaigns also employ normative Hindu imagery in an attempt to address violence against all types of Indian women, it is necessary to consider the ways that the ‘every woman’ in Indian media is often depicted with a very specific Hindu identity.“In the absence of information about the rape victim’s identity, her story struck a chord with protestors because what happened to her could have happened to any of the protestors: her story represented the perils faced by ‘everywoman’ in India. While the notion of ‘everywoman’ served as a potential tool for solidarity, bringing together disparate activist groups as well as citizens from all walks of life to the protest, the category was co-opted to mean a Hindu, upper-caste, middle-class woman.

1. Campaign Distribution and Public Responses

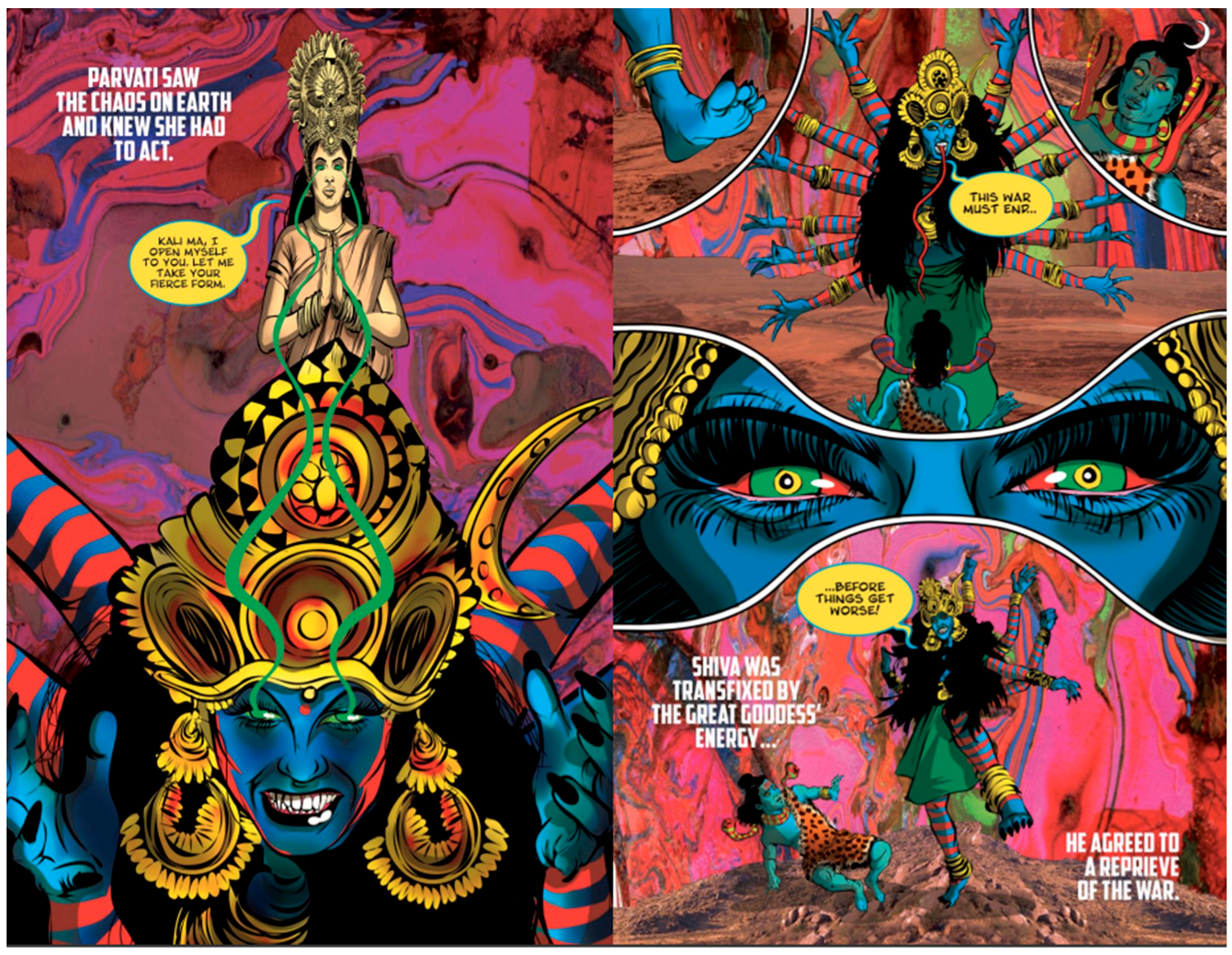

Concerning the murals, Devineni has stated, “We want to make this an iconic image, a reinterpretation of Durga, the ultimate feminist goddess” (Rao 2015, p. 1). The comic book campaign has received many positive accolades across various media channels, both domestic and international, and in 2015 UN Women named Priya “a gender-equality champion” (UN Women 2015, p. 1).Devineni hopes to spread the parallel between Durga and Priya on the streets of India. Working with a non-profit community organization, he enlisted the skills of Bollywood sign painters who live and work in Dharavi, the sprawling, self-sufficient slum inside Mumbai. On walls inside the slum, they produced the comic’s key image: Priya seated atop her own tiger, with a beatific smile not unlike Durga’s. Because of their proximity to the works, the painters—all of whom are men—act as local “representatives” of the cause, Devineni says, fielding questions from local passersby and seeing that the paintings stay untouched.

Similarly, in an interview with Al Jazeera, a Hindu activist of the Universal Society of Hinduism accused the campaign of the “trivialization of highly revered goddesses” (Tilak 2013, p. 1). Both of these responses emphasize the sacrilegious nature of the depiction of beaten goddesses; they imply that through this depiction, the ultimate divine power of the goddess is belittled.It is known that non-Hindus too, are perpetuators of atrocities against women in India. However, this ad campaign specifically blames the Hindu society for the atrocities. To get their message across, the ad-makers have depicted Hindu Deities in a disrespectful manner. This reeks of sheer anti-Hindu bias!

This statement draws our attention to the way that this campaign may fail to represent particular types of women. In general, each of these feminist responses present the argument that this process of deification strips women of the ability to have shifting opinions and flaws and it could be equally as damaging as portraying them as sex objects. For as Praneta Jha observes, Trapping women into images of a supposed ideal is one of the oldest strategies of patriarchy—and if we do not fit the image, it is deemed alright to ‘punish’ and violate us (Jha 2013, p. 1).The deification of prominent and powerful women from fields of movies, music and politics stems from a goddess-worshipping culture13…This is a comfortable image for men and women, not necessarily a feminist strategy. A brand of feminism that is consumer driven and the deification of women as a goddess who is chaste, virginal, and domesticated and clothed, sweeps under the carpet the poor women of those who don’t dress in traditional Hindu attire.

2. Internet, Media, and Representation

Additionally, in their analysis of racism and digital media, Lisa Nakamura and Peter A. Chow White state:First, the Internet is both a representational space and a representation of space. In terms of accessibility and usage it is patently clear that vast discrepancies exist in terms of gender, education and wealth and between a wired core and a less wired periphery. Secondly, the internet has become increasingly commericalised and privatised, transforming the universality of the medium. Both these trends threaten at best to reduce the progressive potential of the internet and at worst to reinforce existing structural inequalities within the global political economy.

While Abbott’s statement encourages us to consider digital media as another representation of already existing offline social hierarchies, Nakamura and White outline how digital media can serve to perpetuate forms of exclusion even further.Digital media technology creates and hosts the social networks, virtual worlds, online communities, new (plat)forms of economic and social exclusion, and both new and old styles of race as code, interaction, and image.

3. Abused Goddesses: Portraying the Conventional, Neglecting the Marginal

I do not include this statement to debate its historical veracity, nor to propose that Savithribai Phule be mobilized in these campaigns in the place of Saraswati. Instead, this statement offers a glimpse at how Dalit experience may interact with the symbol of Saraswati. The statement exposes how, for Dalits, the goddess Saraswati holds in her body a particular image of patriarchy that could not serve as inspiration for the masses. Subsequently, in this passage Ilaiah also associates the god Brahma with the Brahmin community and therefore the god is reprehended for Brahmin exploitation of Dalits, and Saraswati is equally held accountable as his wife.The first woman who worked to provide education for all women is Savithribai Phule, wife of Mahatma Phule21 in the mid-nineteenth century. To our Dalitbahujan mind, there is no way in which Saraswathi can be compared to Savithribai Phule. In Savithribai Phule one finds real feminist assertion. She took up independent positions and even rejected several suggestions made by Jyotirao Phule. Saraswathi, the Goddess, never did that. Her husband, Brahma, is a Brahmin in all respects—in colour, in costumes–and also in the alienation from all productive work. He was responsible for manipulating the producers—the Dalitbahujanas–into becoming slaves of his caste/class. Though [Saraswathi] was said to be the source of education, she never represented the case of Brahmin women who had themselves been denied education, and of course she never thought of the Dalitbahujan women. She herself remains a tool in the hands of Brahma. She becomes delicate because Brahma wants her to be delicate. She is portrayed as an expert in the strictly defined female activities of serving Brahma or playing the veena–always to amuse Brahma”.

In this passage, Ilaiah directly attributes Dalit oppression to the actions of Hindu gods and goddesses in Hindu mythology. Additionally, he highlights the direct connection that devotees are able to have with the Dalitbahujan goddesses/gods in contrast with the Brahmanical gods who often require specialized intermediaries, which further entrenches hierarchical relationships between caste groups. Ilaiah’s critique forces us to consider the ways that the goddesses mobilized in this campaign might ostracize low-caste women, a problem that has been labelled as the ‘Brahminization of the women’s movement’. Indeed Vasanth Kannabiran and Kalpana Kannabiran note that the campaign:The cultural, economic and political ethos of these Goddesses/Gods is entirely different from Hindu hegemonic Gods and Goddesses. The Dalitbahujan Goddesses/Gods22 are culturally rooted in production, protection and procreation...There is little or no distance between the Gods and Goddesses and people…To whatever extent it exists, and contact is needed, the route between the deity and people is direct. Barriers like language, sloka or mantra are not erected…The Hindu Gods are basically war heroes and mostly from wars conducted against Dalitbahujans in order to create a society where exploitation and inequality are part of the very structure that creates and maintains the caste system.

A challenge is issued here for the ways that images of Hindu goddesses and their Shakti potentially marginalize Dalit women.…raised the question of whether the feminist movement itself has been subsumed within a dominant, upper-caste identity that has become complicit in consolidating majoritarian hegemony by virtue of ignoring differences and excluding dalit and minority consciousness. The contradictory deployment of dominant Hindu icons such as Durga and Kali as empowering symbols and images reflects this majoritarian positioning of a radical movement that has these very symbols in recognition of its own alienation from the cultural needs of the people.

This example highlights an instance of a Dalit recognition of the stereotypical nature of normative markers of status, and it additionally offers an example of response and action undertaken by Dalit women in rejection of these stereotypes.Ambedkar asks the dalit women to give up their excessive metal jewellery, and dress patterns that were both public markers of brahmanical caste and gender codes. Giving these up was at once an assertion against the brahmanical and intra-caste patriarchies that deny women the right to exit.

4. Priya’s Shakti: Depicting Violence, Questioning Agency

- Speak without shame,

- And stand with me.

- Bring about the change

- You want to see.

- Like Savitri27 who outwitted death,

- Like the women who helped India gain independence,

- And continue to vote their conscience,

- And the women who have taken on the struggle.

Here Chandra is linking the discourse at work in the ACK series with a larger discourse of Hindu secularism (masked as ‘Indian secularism’) at work in much right-wing political rhetoric today.ACK’s patriotism selectively drew from a reified Hindu past, and could at best claim a trans-regional Hindu purview based on its down-playing of caste and class divisions, yet it aspired for something more. ACK sought to project a secularism, which was defined along Hindu lines. This Hindu secularism is not viable, both because ‘its mode of toleration has historically included absorption, subjugation and marginalization of religious minorities’ (Tharamangalam) and because its expanse is so large that it threatens to lose sight of itself unless it is defined against some ‘other’. This ‘other’ conventionally takes the form of Muslims and Dalits.

5. Conclusions

How does one begin to acknowledge many forms of violence faced by women in identity-based terms? Failure to engage adequately with the complex issue of identity in the context of violence against women was hideously highlighted in the Gujarat carnage of 2002. Scores of women were brutally raped and sexually assaulted in myriad ways because they were Muslim, not just because they were women.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, Jason P. 2001. Democracy@Internet.asia? The Challenges to the Emancipatory Potential of the Net: Lessons from China and Malaysia. Third World Quarterly 22: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnes, Flavia. 1995. Redefining the Agenda of the Women’s Movement within a Secular Framework. In Women in Right Wing Movements: Indian Experiences. Edited by Tanika Sarkar and Urvashi Butalia. London: Zed Books, pp. 136–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ansair, Humaira. 2014. Priya’s Shakti: A Comic on Rape that is More Than a Book. Hindustan Times. December 14. Available online: www.hindustantimes/books/priya-s-shakti-a-comic-on-rape-that-is-more-than-a-book/story-OwQ1KfGvRiHQmkzkzjiYJqN.html (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Banerjee, Sumanta. 2009. Bogey of the Bawdy: Changing Concept of ‘Obscenity’ in 19th Century Bengali Culture. Economic & Political Weekly 22: 1197–206. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. 2018. Dark is Divine: What Colour are Indian Gods and Goddesses? BBC News. January 21. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-42637998 (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Biernacki, Lorelai. 2007. Renowned Goddess of Desire: Women, Sex, and Speech in Tantra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, Brinda. 2013. No More Goddesses, Please Bring in the Sluts. Open Magazine. September 11. Available online: www.openthemagazine.com/article/arts-letters/no-more-goddesses-please-bring-the-sluts.com (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Brown, Cheever Mackenzie. 1990. The Triumph of the Goddess: The Canonical Models and Theological Visions of the Devi-Bhagavata Purana. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoza, Kavitha, and Radhika E. Parameswaran. 2009. Immortal Comic Books, Epidermal Politics: Representations of Gender and Colorism in India. Journal of Children and Media 3: 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Rise of the Network Society. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, Nandini. 2008. The Classic Popular: Amar Chitra Katha, 1967–2007. New Delhi: Yoda Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chauduri, Maitrayee. 2015. National and Global Media Discourse after the Savage Death of ‘Nirbhaya’: Instant Access and Unequal Knowledge. In Studying Youth, Media, and Gender in Post-Liberalisation India. Edited by Nadja-Christina Schneider and Fritzi-Marie Titzmann. Berlin: Frank and Timme, pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Deo, Nandini. 2016. Mobilizing Religion and Gender in India: The Role of Activism. Oxon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Devineni, Ram. 2015. I Stand with Priya. TedXCoventGardenWomen Video, 9:29. July 15. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UuGR0xcyTZE (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Dickson, Ariel. 2019. In Discussion with the Author. Online, March 20. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Gabriele. 2003. Dalit Movement and Women’s Movements. In Gender & Caste. Edited by Anupama Rao. New Delhi: Kali for Women, pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Erndl, Kathleen. 2000. A Trance Healing Session with Mataji. In Tantra in Practice. Edited by David Gordon White. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Erndl, Kathleen M., and Alf Hiltebeitel. 2000. Introduction: Writing Goddesses, Goddesses Writing, and Other Scholarly Concerns. In Is the Goddess a Feminist? Politics of South Asian Goddesses. Edited by Kathleen M. Erndl and Alf Hiltebeitel. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Guru, Gopal. 1995. Dalit Women Talk Differently. Economic & Political Weekly 30: 2548–550. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, John Stratton. 1995. The Saints Subdued: Domestic Virtue and National Integration in Amar Chitra Katha. In Media and the Transformation of Religion in South Asia. Edited by Lawrence A. Babb and Susan S. Wadley. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 107–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hindu Janajagruti Samiti. 2013. Protest: ‘Abused Goddesses’ Campaign Condemning Domestic Violence Denigrate Hindu Deities. Available online: www.hindujagruti.org/news/17352_abused-goddesses-campaign-denigrate-hindu-deities.html (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Humes, Cynthia. 2003. Is the Devi Mahatmya a Feminist Scripture? In Is the Goddess a Feminist? Politics of South Asian Goddesses. Edited by Kathleen M. Erndl and Alf Hiltebeitel. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 123–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ilaiah, Kancha. 1996. Why I Am Not a Hindu: A Sudra Critique of Hindutva Philosophy, Culture, and Political Economy. Calcutta: Samya. [Google Scholar]

- Jha, Praneta. 2013. Abused or Not, Women Are Not Goddesses. Hindustan Times. September 10. Available online: www.Hindustantimes.com/art-and-culture/abused-or-not-women-are-not-goddesses/story-crcegadEHUagpZBtNg3VYP.html (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Kannabiran, Kalpana, and Vasanth Kannabiran. 1997. Looking at Ourselves: The Women’s Movement in Hyderabad. In Feminist Geneologies, Colonial Legacies, Democratic Futures. Edited by M. Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Talpade Mohanty. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 214–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsley, David. 1986. Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine in Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, Anja. 2004. You Don’t Understand, We are at War! Refashioning Durga in the Service of Hindu Nationalism. Contemporary South Asia 3: 373–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manas, Puhup. 2015. Scars of a Culture. Intertext 23: 50. [Google Scholar]

- McLain, Karline. 2008. Holy Superheroine: A Comic Book Interpretation of the Devi-Mahatmya Scripture. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 71: 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain Karline. 2009. India’s Immortal Comic Books: Gods, Kings, and Other Heroes. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNally, Victoria. 2014. New Superhero Comic Confronts India’s Rape Culture Head-On. The Mary Sue. December 11. Available online: https://www.themarysue.com/india-comic-priya-shakti/ (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- Nakamura, Lisa, and Peter A. Chow White. 2012. Race after the Internet. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, Farah. 2010. This Thing Called Justice: Engaging with Laws on Violence Against Women in India. In Nine Degrees of Justice: New Perspectives on Violence against Women in India. Edited by Bishakha Datta. New Delhi: Zubaan. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, Geeta. 2014. India’s New Comic ‘Super Hero’: Priya, the Rape Survivor. BBC News. December 8. Available online: www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-30288173 (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Pinney, Christopher. 2004. Photos of the Gods: The Printed Image and Political Struggle in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett, Frances. 1995. The World of Amar Chitra Katha. In Media and the Transformation of Religion in South Asia. Edited by Lawrence A. Babb and Susan S. Wadley. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 76–106. [Google Scholar]

- Priya’s Shakti. 2013. NGO Partner Apne Aap Women Worldwide. Available online: http:www.priyashakti.com/apne_aap/ (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi. 2010. The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Anupama. 2009. The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Mallika. 2015. Here’s Why the Biggest Slum in India is Honoring a Fictional Rape Victim. The Huffington Post. May 26. Available online: www.huffingtonpost.ca/entry/priyas-shakti-street-art_n_7294470 (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Rege, Sharmila. 2006. Writing Caste/Writing Gender: Reading Dalit Women’s Testimonios. New Delhi: Zubaan. [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold, Howard. 1992. Virtual Reality: The Revolutionary Technology of Computer-Generated Artificial Worlds and How It Promises to Transform Society. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Vaisha. 2013. Goddess under Attack. The Hindu. September 15. Available online: thehindu.com/features/the-yin-thing/goddess-under-attack/article512905.ece (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Sarkar, Tanika. 2001. Hindu Wife, Hindu Nation: Community, Religion, and Cultural Nationalism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shandilya, Krupa. 2015. Nirbhaya’s Body: The Politics of Protest in the Aftermath of the 2012 Delhi Gang Rape. Gender & History 27: 465–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sherma, Rita DasGupta. 2000. ‘Sa Ham—I Am She’: Woman as Goddess. In Is the Goddess a Feminist? Politics of South Asian Goddesses. Edited by Kathleen M. Erndl and Alf Hiltebeitel. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 24–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sunder Rajan, Rajeswari. 2000. Real and Imagined Goddesses: A Debate. In Is the Goddess a Feminist? Politics of South Asian Goddesses. Edited by Kathleen M. Erndl and Alf Hiltebeitel. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 269–84. [Google Scholar]

- Suri, Pradeep Kumar, Anurga Tiruwa, and Rajan Yadav. 2014. Going Viral: An Effective Strategy for Marketing. In Research and Sustainable Business. Edited by Mukesh Kumar Barua and Ziller Rahman. New Delhi: Excel India Publishers, pp. 598–603. [Google Scholar]

- Tawa Lama, Stephanie. 2001. The Hindu Goddess and Women’s Political Representation in South Asia: Symbolic Resource or Feminine Mystique? International Review of Sociology 11: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teltumbde, Anand. 2013. Delhi Gang Rape Case: Some Uncomfortable Questions. Economic & Political Weekly 48: 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tilak, Sudha G. 2013. Bruised Goddesses Hurt Indian Feminists. Aljazeera. October 10. Available online: www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/10/goddesses-hurt-indian-feminists-2013105104822923415.html (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- UN Women. 2015. Gender Equality Champions. Available online: Beijing20.unwomen.org/en/voices-and-profiles/champions#ram (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Urban, Hugh. 2003. Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics and Power in the Study of Religion. Berkeley: University of California press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Rita DasGupta Sherma notes that this identification is found in the Devi Mahatmya 11.4, but she also highlights that the identification was not emphasized in the Shakta tradition, and that it is only in Shakta-tantra that “the Goddess-woman identification is stressed, and women’s right to religious self-determination is affirmed” (Sherma 2000, p. 33). |

| 2 | |

| 3 | This emphasis on motherhood possibly contributes to the way that society heavily values women through their relational roles (mother, wife) rather than as individual women. The two campaigns I discuss remind both men and women of the value of the individual woman outside of her relationships. |

| 4 | Taproot India, the Mumbai-based ad agency which produced these images, states, “Hand-painted posters of Gods and Goddesses can be found in every place of work, worship and residence (in India). Hence, we recreated the hand-painted poster style to emotionally communicate to the target group” (Manas 2015, p. 50). |

| 5 | This idealized Indian womanhood became the symbol of the Indian nation in Nationalist politics pre-Independence (visually depicted by the goddess Bharatmata), and continues to this day in Hindu Nationalist rhetoric and imagery. In Nationalist political rhetoric, human women are often conflated with Bharatmata, as they are both depicted as bearers and protectors of tradition. While women are consigned to the role of the protectors of the nation, the Nationalist movement’s invocation of the goddess did, in some sense, legitimize women’s participation in activism in ways that had rarely been available to Indian women in the past. Stephanie Tawa Lama argues that the translation of political activism into religious terms transforms the nature of political activism, opening it up to women as well (Tawa Lama 2001). Debates concerning the empowering potential of the goddess continue today with a focus on Hindu Nationalist mobilizations of the goddess symbol to encourage female participation. For instance, scholars like Sarkar (2001) and Anja Kovacs (2004) have argued that these mobilizations do open up space for public participation and empowerment in some sense, but that it is a bounded notion of empowerment. Kovacs (2004) notes that while Hindu Nationalist women often gain status in their families and communities, in general, Hindutva diverts Indian women’s attention and wrath away from their own oppression towards a vilified ‘other, and in the end patriarchy prevails. |

| 6 | Anand Teltumbde has similarily questioned why atrocious rapes against Dalit women, such as that of Surekha and Priyanka Bhotmange in Khairlangi just days before the Nirbhaya incicdent, have gone unnoticed by progressives and the media despite Dalit protests (Teltumbde 2013). |

| 7 | I have surveyed references to these campaigns on online blogs, international newspapers, and English-language Indian newspapers. |

| 8 | In my personal communication with Ariel Dickson, the Lion’s Quest Program Specialist, Priya’s Shakti had a limited distribution in schools, while the comic’s sequel, Priya’s Mirr,r had a more extensive distribution. The gender-adapted Lion’s Quest Program which distributed these books is currently only in English and targeted specifically towards students age 11–12 (Dickson 2019). |

| 9 | Save Our Sisters (SOS) works to prevent the sex trafficking of young girls. |

| 10 | The original ScoopWhoop article is no longer available online, but there were a variety of comments on the Buzzfeed article ranging from “praiseworthy” to “blasphemous”, cf. (Jha 2013). |

| 11 | For an example of this type of praise, cf. (Jha 2013). |

| 12 | Additionally, to date, I am not aware of any coverage of this campaign in Indian language news media aside from English channels. |

| 13 | The deification of powerful women in media and politics can be clearly witnessed in the examples of Jayalalitha Jayaram, who served as the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu until 2016 and who was revered as Nadamadum (Walking Goddess) and Adi Parashakti (The Primordial Power), as well as the media conflations of Indira Gandhi with the goddess Durga in the 1980’s. |

| 14 | For examples of optimistic attitudes towards the democratization of the internet, cf. (Castells 1996) and (Rheingold 1992). |

| 15 | For examples, see interviews with Ram Devineni on the Priya’s Shakti Press webpage, c.f. (Priya’s Shakti 2013). |

| 16 | In her comments on an earlier draft, Patricia Dold highlights that as the Abused Goddesses campaign is now only available online, and only in English, it most likely has primarily reached a middle class audience. This risks the reinforcement of the middle class’s “claim to represent all other Hindu and Indian culture” (Dold 2019). |

| 17 | This style of calendar art was pioneered by Raja Ravi Varma during the colonial period. Christopher Pinney discusses how Ravi Varma’s images animated the new voice of the emerging nation imagined by Nationalists at the time (Pinney 2004). Therefore, this style of depiction has always been embedded with a form of Nationalist politics which has articulated a specific type of acceptable femininity. |

| 18 | The goddesses are depicted in the beautiful and lush background that is characteristic of calendar art (this perpetuates notions of the perfection of the god realm). The picturesque background drastically contrasts with the brutal marks of violence on the faces, and while this evidently emphasizes the shock value of this campaign, these backgrounds potentially also serve to glamourize violence in particular ways. |

| 19 | Perhaps through the shifted gaze onto the women in the side bars, the viewer is further confronted with the question of why the image of the beaten goddess induces shock differently from that of the sight of a beaten human woman (Dold 2019). |

| 20 | These three goddesses are commonly depicted together, as they are seen in many Shakta contexts as the counterpart to the trimurti of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. The Devi-Bhagavata Purana in particular identifies Maha-Lakshmi and Maha-Saraswati (along with Maha-Kali) as the three revelations of the power of Devi, the Great Goddess of the Devi-Mahatmya (Brown 1990). Dold highlights that this choice of goddess speaks to the creator’s choice to use images that would specifically resonate with a Hindu audience (Dold 2019). |

| 21 | Jyotirao Phule was a 19th century Indian social reformer and anti-caste activist who is considered a hero by the contemporary Dalit movement. |

| 22 | Ilaiah offers the examples of two South Indian goddesses: Pochamma, who demonstrates a gender-neutral, caste-neutral and class-neutral relationship to human beings, and Polimeramma, who guards entire villages from illness, irrespective of the class or caste makeup of that village (Ilaiah 1996). |

| 23 | It is not the goddess calling out for recognition of violence in the copy, instead a third-party narrator. |

| 24 | Radhika E. Parameswaran and Kavitha Cardoza offer the following examples of this dominant media culture: “Matrimonial classified advertisements in Indian newspapers specify routinely that prospective grooms prefer women with ‘‘fair’’ or ‘‘wheatish’’ complexions. A majority of the Indian female actors in Bollywood are light-skinned women, and the few dark-skinned women actors who have overcome the restrictive norms of skin color wear thick make-up to conceal their dark facial skin. Interweaving colorism into a seamless package of physical attributes, the faces of Indian models in advertisements are almost universally light-skinned with smooth complexions, shining black hair, and slim bodies. The most lucrative products in the Indian cosmetics sector since 1998, a decade after India’s initial incorporation into the global economy, are chemical and herbal products that promise to reduce darkness and preserve light skin by preventing further tanning” (Cardoza and Parameswaran 2009, p. 22). |

| 25 | As a counterpoint, recent years have seen the mobilization of several social media campaigns addressing the under-representation of dark skin in media including Dark is Beautiful and “unfairandlovely”. Furthermore, 2018 also saw the release of the photo campaign “Dark is Divine” that portrays gods and goddesses with dark skin in order to both provide an accurate depiction of the divine, and to challenge views that see fair skin as superior (BBC News 2018). |

| 26 | Additionally, Gabriele Dietrich highlights the difference in the way women from different castes are subjected to violence, and the difference in how their cases are received in court: “It is true that violence against women cuts across caste and class, especially in an urban context. However, the circumstances differ. Cases of dowry connected with torture and murder are more frequent among upper castes and it is probably not exaggerated to say that family violence among upper castes tends to be quite systematic. This type of systematised family violence occurs much less among backward castes and Dalits unless they have become economically prosperous and try to imitate upper caste values, which is rare […] However, they face the collective threat of physical harm from upper caste forces all the time […] At the same time, such violence is often taken as “normal” and rape cases tend to be compromised or cheaply compensated in an overall bargain to settle the caste issue” (Dietrich 2003, p. 58). Anupama Rao additionally highlights that verbal and physical violation of the female Dalit body is often used as a method of anti-Dalit violence enacted by upper-castes to protest the state’s legislation of Dalits as exceptional bodies (Rao 2009, p. 29). |

| 27 | Savitri is a famous female figure from the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata. Specifically, she is famous for outsmarting the god of death Yama in order to bring her husband Satyavan back from the dead. She is most prominently revered as the epitome of a faithful and dedicated wife, although feminists tend to emphasize her cunning and courageous behavior over her obedience. |

| 28 | Devineni explains that the tiger represents Priya’s fear (which is then transformed into her own form of Shakti when Parvati tells Priya she needs to look the tiger in the eye and turn fear into power) in a Tedx talk (Devineni 2015) (Figure 7). |

| 29 | David Kinsley notices that Parvati is primarily known in her role as ‘a wife’ and that she is not worshipped independently, in contrast to the goddess Durga (Kinsley 1986). |

| 30 | Several scholars have exposed the ways in which the symbol of Kali represents both the status of women in India during the Modern period, and the changing attitudes towards the diverse sectarian forms of religion found in the country, cf. (Humes 2003; Urban 2003; Banerjee 2009). Throughout the years, whether it is the sweetening of her image into that of a mother, the demonizing into that of the devilish whore, or the possessing that of the weakened and thirsty, the diverse re-imaginings of the goddess Kali expose the various constructions of ideal Indian femininity propagated by both the British and Indian reformers. Therefore, I consider this sanitized depiction of Kali as a continuation of this project. |

| 31 | Karline McLain also highlights how prominent Hindu nationalist politicians were quick to endorse the ACK series (McLain 2009). |

| 32 | Alongside these stories, animations highlighting statistics and resources concerning violence against women also appear throughout. |

| 33 | Nandini Deo also addresses the notion of ‘woman’ as a category: “The difficulty in mobilizing women qua women is that they are divided in exactly the same ways their societies are. Caste, class, religion, language, and ethnic cleavages in a society are mirrored among women. The experience of being a woman is never isolated from all the other characteristics of a person” (Deo 2016, p. 10). |

| 34 | This can be seen, for instance, when Priya’s family and community reject her in shame after she is assaulted. |

| 35 | For example, the popular cultures news blog The Mary Sue notes that the comic book offers a “deep understanding of the issue of sexual violence”, yet in its headline and body, the blog emphasizes specifically “India’s rape culture” without any mention of the ways that sexual violence and rape is a global issue, and women from many countries are able to access the pages and messages of this comic book (McNally 2014, p. 1). |

| 36 | For example, this narrative potentially ignores the notable successes of the Indian Women’s Movement and the way it has effectively influenced policy and law-making. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smears, A. Mobilizing Shakti: Hindu Goddesses and Campaigns Against Gender-Based Violence. Religions 2019, 10, 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060381

Smears A. Mobilizing Shakti: Hindu Goddesses and Campaigns Against Gender-Based Violence. Religions. 2019; 10(6):381. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060381

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmears, Ali. 2019. "Mobilizing Shakti: Hindu Goddesses and Campaigns Against Gender-Based Violence" Religions 10, no. 6: 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060381

APA StyleSmears, A. (2019). Mobilizing Shakti: Hindu Goddesses and Campaigns Against Gender-Based Violence. Religions, 10(6), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060381