Abstract

This paper focuses on the relationship between clothing and identity—specifically, on Islamic dress as shaping the identity of Dutch Muslim women. How do these Dutch Muslim women shape their identity in a way that it is both Dutch and Muslim? Do they mix Dutch parameters in their Muslim identity, while at the same time intersplicing Islamic principles in their Dutch sense of self? This study is based on two ethnographies conducted in the city of Amsterdam, the first occurring from September to October 2009, and the second took place in August 2018, which combines insights taken from in-depth interviews with Dutch Muslim women and observations in gatherings from Quranic and Religious studies, social gatherings and one-time events, as well as observations in stores for Islamic fashion and museums in Amsterdam. This study takes as its theme clothing and identity, and how Islamic clothing can be mobilized by Dutch Muslim women in service of identity formation. The study takes place in a context, the Netherlands, where Islam is largely considered by the populous as a religion that is oppressive and discriminatory to women. This paper argues that in the context of being Dutch and Muslim, through choice of clothing, these women express their agency: their ability to choose and act in social action, thus pushing the limits of archetypal Dutch identity while simultaneously stretching the meaning of Islam to craft their own identity, one that is influenced by themes of immigration, belongingness, ethnicity, religious knowledge and gender.

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on a vital issue in academia and civil society: the growing interest in Muslim populations in Europe, and the lives of Muslims in a non-Muslim world. Here, we present a unique perspective on this topic by focusing on the lives of Muslim women in the Netherlands, as manifested through their daily decisions regarding religious dress.

The issue of integration also presents tensions among Muslims (newly practicing born Muslims as well as converts, sometimes referred to as ‘New Muslims’) and Dutch society, which we will describe in this paper. Scholars of religion argue that various religious groups are currently engaged in questioning norms, ideologies, practices and gender roles that are widely accepted in their communities (Abu-Lughod 1998, 2002; Avishai 2008; El Or 2012; Mahmood 2001; Stadler 2009). For example, Avishai shows that in her ethnography, the women she studied may experience conservative religions as restricting, they are also liberated and empowered by their religion. Thus, their ‘compliance’ in religion may not be strategic at all, but rather a mode of conduct and being. Expanding on Butler’s notion of “doing gender” discussed also by West and Zimmerman (Butler 1990; West and Zimmerman 1987), Avishai’s focus is on the construction of religiosity by means of conceptualizing the agency of the women involved in her research as “doing religion.” “Doing religion” is in fact a performance of identity, and, in so far as this performativity can be viewed as a strategic undertaking, possibly done in the pursuit of religious goals (Avishai 2008). Furthermore, Shatdler, Elor, Mahmood and Abu Lughud also show in their studies how members of religious communities in Islam, Christianity and Judaism engage in integrating medieval and holy texts and ways of life with modern ideals and practices (Abu-Lughod 1998; Ammerman 1987, 2005; El Or 2006; Mahmood 2001; Stadler 2009). In this study, we inquire as to whether, and how, Muslim groups in the Netherlands struggle with these tensions in terms of being new (converts) or newly practicing (born Muslim, but embracing religion later in life) in their faith, and thus the practice of their religion in the context of being a Muslim in a non-Muslim country. This work will focus on Dutch Muslimas; native Dutch women who have chosen to embrace Islam at different stages of practice (often referred to as New Muslims) and born Muslim women who started to practice at a later stage of life also referred to as conversion, according to Rambo’s conversion model, (Rambo 1999) (often referred to as Newly Practicing Muslims) since these women often befriend each other and study together in women-only Quranic classes, workshops, Arabic language classes and many other gatherings (see also in (Hass 2011; Hass and Lutek 2018; Vroon 2014)).

Here, in this paper, we specifically focus on dress and covering as an active probe. It will be explained how these choices can be about fashion and anti-fashion (Tarlo and Moors 2013), the aesthetic of covering (Tarlo and Moors 2013; Moors 2013), through a theoretical framework of modesty (Boulanouar 2006; Moors 2013; Siraj 2011; Stephens 1972), and how through these choices, women express their (a) agency, which is their ability to choose and act in social action, (b) and their identity, as they push the limits of archetypal Dutch identity, while simultaneously stretching the meaning of Islam to craft their own image influenced by themes of immigration, belongingness, knowledge, ethnicity, religious knowledge, higher education and gender.

Here, it is important to understand: many capitalist societies are characterized by a belief that “to have is to be” (Dittmar 1992). Related to this is the idea that, in life, meaning, achievement and satisfaction are often judged in terms of what possessions have or have not been acquired (O’Cass 2004; Richins, 1994). Thus, possessions have come to serve as key symbols for personal qualities, attachments and interests, and, as Dittmar (Dittmar 1992) has said, “an individual’s identity is influenced by the symbolic meanings of his or her own material possessions, and the way in which s/he relates to those possessions” (Dittmar 1992). Such a reality valorizes our approach, solidifying the notion that in modern capitalist countries, such as the Netherlands, possessions, and specifically symbolic possessions such as clothing, function as component materials in the building of identity and self.

Here, it is worthwhile to dwell deeper into identity and self-building, by looking at the works of Entwistle and Wilson, and Tarlo. Entwistle and Wilson argue that clothes constitute the clear separation and boundary between the perceived self and the external world, or not self. Clothing is thus the boundary between the self and the not self (Entwistle and Wilson 2001). Tarlo also contributes to this argument by claiming (Tarlo 1996) that clothing has a unique and unusual role in perceptions and building of identity (Tarlo 1996). This includes questions which ask what clothes mean for the person who wears them, why individuals and groups choose to dress a certain way, etc. She argues answering such questions shows that clothes are central to a person’s identity. In her work, she places the question of “what to wear?” as a key question not only in perceiving the identity of the individual, but also as a methodological tool for understanding and investigating a particular culture. Deciding what to wear is one of the ways in which people try to manifest meaning and externalize themselves. According to Tarlo, the closeness of the clothes to the body in particular, showcases them as objects which have great capacity for symbolic expansion (Tarlo 1996).

1.1. Fashion, Anti-Fashion and Islamic Fashion

“O Prophet! Say to your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers that they let down upon them their over-garments; this will be more proper, that they may be known, and thus they will not be given trouble; and Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.”(Quran, chapter 33, verse 59, Shakir translation)

Across Europe, a cohort of young Muslim women is at the vanguard of new styles of modest fashion, combining mainstream trends with inventive forms of hijab and Islamic clothing (Bartels 2005; Lewis 2013; Moors 2007, 2013; Rambo and Bauman 2012; Tarlo 1996; Tarlo and Moors 2013; Van Nieuwkerk 2003a, 2003b, 2004). The same phenomena can also be seen specifically in the Netherlands (Bartels 2000; Moors 2007; Van Nieuwkerk 2003a, 2003b, 2004, 2014), Finland (Almila 2016); Sweden (Roald 2004, 2012), Scotland (Boulanouar 2006); Germany (Özyürek 2010, 2014) and France (Bowen 2007, 2010). As O’Cass (O’Cass 2004) has argued, these women developed a strong subjective perception of product knowledge and expertise in the product, strongly influenced by their involvement in fashion clothing, as modern fashionable Muslim women. However, unlike other celebrated instances of British street style, these style innovations are rarely recognized as such by the mainstream global fashion media. In popular discourse, the hijab is often seen as a controversial symbol, rarely as a piece of clothing (Bowen 2007, 2010; Tarlo and Moors 2013). Scholarly interest in Muslim fashions tends to focus on Muslims as consumers rather than as participants in the mainstream fashion industry, showing the construction of a false binary between the two (Lewis 2013).

In this context, Akou (Akou 2007) comments on the concepts of “ethnic dress” and “world fashion” along with the common perception that there is only one world fashion system dominated by the West. Although Paris is no longer the center of fashion, names such as Chanel, Dior, Vogue and Elle are still prominent in the minds of scholars and consumers alike. In the past, garments that were not directly connected to this Western fashion system tended to be labeled as “ethnic dress” or even “folk costume” (Akou 2007; Baizerman et al. 2008; Tarlo and Moors 2013). A new framework—based on micro cultures, cultures, and macro cultures—can allow us to recognize non-Western fashion systems that have a global reach. For example, Asian, African, and Islamic dress appeal to consumers in multiple nations and should not simply be considered through the Western lens of “ethnic dress” (Akou 2007). Important to note is that such a labelling is indeed deeply problematic. That some clothing is labelled as ethnic (which can be understood as a whitewashing euphemism for ‘other’ or “foreign”), while others are accepted as natural, highlights the troubling way Western society puts Islamic clothing in an imagined Western/Eastern binary, which in reality is an artificial sociological construction.

In recent years, Islamic businesses and consumers have also been building a new “world fashion,” distinct from Western fashion and often opposed to many Western stereotypes of what beauty is (Akou 2007; Tarlo and Moors 2013). Like Western-world fashion, which is based around specific cities, designers, publications (like Vogue and Elle), and even styles of garments (skirts, business suits, jeans, T-shirts)—no matter how much an author or designer might try to think outside of the box—certain aspects of Islamic dress are also privileged. The names of the garments (hijab, khirtmr, dishdash, smagh, khimar and many more) are usually discussed using their Arabic name. Arguments for and against wearing them refer to the Quran and Hadiths, the teachings of the Prophet Mohammed, with certain countries being known as a source of fashion trends. Akou (Akou 2007) analyzes the similarities between Islamic fashion websites as an example of a non-Western world fashion system. These sites, geared primarily toward Muslim women living outside of the Islamic world (including North America and Europe), give consumers several advantages over going to the local mall or even to the Muslim tailor in their neighborhood. On these sites, the styles and names of garments are similar if not identical to what Muslims wear in countries such as Turkey, Egypt, and Jordan. The clothing is always modest; and the businesses offer a shopping experience in tune with Muslim values and offer a wide range of choice. In addition to clothing for women and sometimes men and children, many of the sites offer quotes from the Quran, a “Hadith of the day” (comments on the message and lifestyle of the prophet Mohammed), discussion boards, and even advice on how to wrap a headscarf. In recent years, as the technology and speed of the Internet has improved, these websites have begun to play a vital role in spreading fashions between different parts of the Islamic world (Akou 2007). In this regard, it is important to stress meanings Muslim women give to modesty. Boulanouar’s ethnography revealed differences as well as similarities between wearers and non-wearers of the hijab. While the wearers regard the hijab as an embodiment of modesty, virtue and respect, the non-wearers sometimes consider it an unnecessary piece of clothing. However, despite their contrasting views on veiling, both groups of participants hold remarkably similar views on the importance of female modesty (Boulanouar 2006).

As Islam is a religion, yet also a way of life (din) and modesty is central to it, modesty in clothing is an obvious component. The discussion on clothing presented here focuses mainly on women’s clothing, and women’s clothing in the public sphere (i.e., clothing that is worn in the company of strangers). The public sphere is defined here as ‘in the company of strangers’ rather than ‘outside the home’, although often these two situations correspond. Consequently, the definitions of ‘public space’ and ‘private space’ in Islam differ from those in a Western paradigm (El Guindi 1999; Tavris 1993). There exist several requirements and prohibitions concerning clothing in Islamic teachings. Essentially, the awra’ (an Arabic term meaning ‘inviolate vulnerability’) must be covered, but the method or style of coverage varies greatly from country to country and person to person (Boulanouar 2006; El Guindi 1999). Below, we briefly introduce two key elements of modern Islamic clothing.

1.2. Hip in Hijab

“I put it on, I took it off … ‘Why did I wear a hijab?’… this was a question that I was asked a lot, and that I had also asked myself … I feel that I am doing this out of solidarity … solidarity with people who wear it and are attacked for it … the hijab indicates modesty and protection, but in my opinion it’s not just that … it’s a lot of other things that merge together…”(Leyla, 28 years old)

Recent decades have seen the growth and spread of debates about the visible presence of Islamic dress in the streets of the Netherlands, the UK, Germany, France and Scandinavia (Cesari 2005, 2009; Hass and Lutek 2018; Moors 2007, 2013; Tarlo and Moors 2013; Vroon 2014). Moors and Tarlo claim that these debates have intensified after 9/11, with a focus on the apparent rights and wrongs of covering, hijab and face veils, and whether their use is forced or chosen, and to what extend they might indicate the spread of Islamic fundamentalism or pose concerns for security (Moors 2013; Tarlo and Moors 2013). Furthermore, the scholars claim that most of these debates ignore the development and proliferation of what has become known, in Muslim circles and beyond, as Islamic fashion and how the emergence of such a phenomenon does not necessarily signal Muslim alienation from European or American cultural norms, as complex forms of critical and creative engagement with them (Bartkowski and Read 2003; Cesari 2005, 2009; Moors 2007; Tarlo and Moors 2013). Thus, taking a critical distance from the popular assumption that fashion is an exclusively Western or secular phenomenon allows us to understand that the complex dynamics of the fashion industry are in no way limited to the Western world. Rather, Islamic fashion engages with and contributes towards mainstream fashion in various ways, so Muslim critiques of fashion share much in common with critiques from secular and feminist sources (Mernissi 1987; Mernissi 1991; Moors 2013; Tarlo and Moors 2013). The hijab, a head covering worn by tens of millions of Muslim women in the world, is at the forefront of this debate, and will be returned to throughout this article.

1.3. The Overcoat (Pardösü)

One example of Islamic dress, besides the famous hijab, is the overcoat (pardösü in Turkish, with the original word coming from French, pardessus). Arzu Unal (Ünal 2013) explains what this single item of clothing can tell us about Turkish migrant experiences in the Netherlands. Through this particular dress, one can analyze changing styles of wearing overcoats and overcoat fashions among migrant women, originally from Turkey, and thus can explain what overcoat wearing means to different categories of women at different historical moments and in particular locations, such as the location of a new host country, such as the Netherlands. In order to probe this notion of categories, we will also apply the Bhabha’s concept of the “third space” later in the article. A genealogy of the overcoat reveals accounts of continuous engagements with piety and femininity through women’s social-spatial mobility in a transnational field and also of an object in transition. This is a genealogy of wearing overcoats from the first journeys of Anatolian women from small villages to the Netherlands in the 1970s, a few who came as workers, and most who came as fiancés and wives of guest workers (Besamusca and Verheul 2014; Cruz 2016; Ünal 2013). Here, we see European influences on the jilbab, through to the large collections of overcoats found in contemporary wardrobes of Turkish Dutch women. Appadurai (Appadurai 1986) would have argued that the overcoat is an object that can tell us a story, and in fact serves as an interlocutor in a historic or comparative study. The story this specific object can tell us is a story of migration and integration of ethnic and religious minorities in Europe, generation gaps between migrants and their children and grandchildren, changing styles, and similar to non-Islamic clothing: a quest for a retro-style (once again showing similarities between Islamic and non-Islamic clothing, and how such a distinction is truly artificial and generally problematic). We return to this powerfully informative fashion choice throughout our research.

2. Methods

This paper is part of a research project which analyses religious conversion among Dutch women, more specifically, Dutch women who have embraced Islam. The research project includes a multi-sited (Marcus 1995) ethnography conducted in the city of Amsterdam and its suburbs, taking place in two periods over one decade: the first occurring from September to October 2009 (focusing on born Muslims) and the second one occurring in August 2018 (focusing on converts). The Netherlands was specifically chosen thanks to the lived experience of the first author, who was raised in one of Amsterdam’s most vibrant and multicultural neighborhoods. Data were collected and analyzed using various qualitative methods. We conducted 22 in-depth interviews, and we participated in Quranic classes, gatherings, lectures and workshops. The ethnography combines insights taken from over twenty observations, including participant observations in gatherings for Quranic and Religious studies, observations in a Mosque located in a block of neighborhoods with a high percentage of immigrant and Muslim populations, as well as observations in Islamic dress shops in various neighborhoods in Amsterdam. A third source of data we used was cultural artifacts. We analyzed invitations to events, gatherings, distribution materials, photographs, posters, exhibitions in museums, websites and material culture (textile and clothing) as a source of information. Additionally, in order to obtain a deeper understanding of Islamic dress and culture, we also conducted museum ethnography in the Tropen Museum in Amsterdam, a museum full of world cultures, and in the Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem (See Appendix D), The Israel Museum in Jerusalem, Israel as well as in the archives (Rose Archive for textile and fashion) of the Shenkar Academy for engineering, art and design in Ramat Gan, Israel. This research was approved by the Ethics committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study and agreed to a taped interview. Interviews were held and transcribed in Dutch and were sent to all participants for review. Two participants returned the transcript and asked for corrections and edits. A total of 17 interviews were then translated into Hebrew for the master dissertation by the first author (which was written in Hebrew). In June 2018, the first author reopened the files and translated significant parts of the interviews from Dutch to English. In August 2018, another 5 interviews were added: these interviews were held in Dutch, transcribed in Dutch, and significant parts of each interview were translated into English and integrated in the ethnography. Of the participants, 9 were converted Muslimas and 13 were born Muslimas with different ethnic roots (mostly in Turkey and Morocco but also in Suriname, Somalia and more). Most reside in Amsterdam and in the suburbs of the city, and their ages range between 20 and 45. Of the participants, 7 were married or in a committed relationship (leading to marriage) during the ethnography, and the rest defined themselves as single. All participants presented in this manuscript are anonymous and their names have been changed accordingly.

2.1. Engaged Anthropology

Engaged anthropology was a central framework of this study. Engaged anthropology’s primary focus is on sharing the results of anthropological research with a wider audience, rather than only fellow anthropologists. Lamphere (Lamphere 2003) uses a rather broad definition of the term engaged anthropology and argues that, in this view, engaged anthropology possesses three characteristics: it reaches out to the public, it aims to establish ongoing partnerships with the community’s anthropologists, and it examines topics which have relevance to public policy (Lamphere 2003). We believe that this research topic has the potential to deliver insights to the public, to other Dutch Muslim women and men, other Dutch minorities, and even extend as far as policy makers and stakeholders in Dutch society. In the ethnography, it was often observed that the Dutch population is looking at these women through prejudices and stereotypes, seeing them as “Muslim,” “Moroccan,” or calling them “hoofddoekje” (little headscarf), contributing to the feeling of non-belonging, while objectifying them.

Here, it is important to note that those we interviewed and researched were also, following the mandates of engaged anthropology, integrated into the research process. Specifically, the written results of the interviews have been shared with the interlocutors, first by sending them the transcription of their interview and waiting for their comments. Then, in cases when they were interested, the analysis was shared with them. In this way, the interlocutors are not viewed as passive, but rather are actively engaged with us as a true part of the conversation.

2.2. Positionality

Through ethnography, the first author conducted fieldwork in the city she was born and raised in but focused on practices foreign to her. Coming from an ethnic and religious minority herself, the first author identified with the stories of women who have migrant parents. The first author’s life story is one of migration, from Israel to the Netherlands and from the Netherlands to Israel with roots in Eastern Europe, as a grandchild of Holocaust survivors. Positionality is a key feature for any social research. The first author’s gender, for instance, was an important aspect of her ability to execute this research. The Muslimas that she studied practice a strict separation of the sexes during their meetings, and therefore no men are allowed. In this regard, the first author qualifies as an insider, since she shares their gender, ethnicity, nationality and language. However, she does not share the religion of the participants, and that is one aspect where she sometimes felt to be an outsider (Van Nieuwkerk 2003a, 2004; Vroon 2007, 2014).

3. Discussion

3.1. The Beauty of Modesty

The concept of modesty is addressed in Islamic teachings from many angles. In physical terms, modesty is connected with the awra’, an Arabic term meaning ‘inviolate vulnerability’ (Boulanouar 2006; El Guindi 1999; Siraj 2011), or ‘what must be covered’ and consisting of the private body parts of a human being. For men, the awra’ is from the navel to the knee (or mid-thigh in some rulings). For women, the awra’ is more extensive and a more complicated matter entirely. A woman’s awra’, with respect to men outside her close family members and those forever ineligible for marriage to her, and non-Muslim women, consists of her entire body, with the exception of her face and hands (Boulanouar 2006).

The next quote, by one of the main informants in this study showcases a situation in which a converted Muslima expresses the desire to wear a hijab, while her spouse at that time, a born Muslim, encouraged her to think this decision over and not to make any hasty decisions.

“when I converted, I told my ex-husband, I will never wear a headscarf, because then people will never see my face … again … well, I think a few months after, when I had immersed myself more in my Islamic journey … I was more open to it, and I started wearing a headscarf. That was very special … after this I started seeing much more converted women wearing headscarves. At one point I also saw a Dutch woman with a headscarf here in my small town, and I really thought something like … wow … is that even possible, what I am seeing? I also thought something like: ‘if she can do it, I can do it too’

I started thinking a lot about it and I came to the conclusion that the reason for not doing it would be for my family and my friends and for the neighbors and, what they would say about it … then I decided that that is not who I live for … for what my family thinks and what the neighbors think and well … I actually decided fairly quickly then to also to wear a headscarf. In the beginning a shorter and smaller one, just starting slowly … and I remember that my husband then said, ‘Are you sure? Just wait a minute, don’t do it … first check if you are sure about it, so that you won’t tell me next week that I you want to take it off, because that is not the intention of the headscarf. It’s a decision, not a trial period.’

So you see … it is often assumed that women are forced by their husbands … but no, on the contrary, on the contrary … in my case he was the one who tried to stop me.”(Lydia, 36, Converted Muslima)

Another converted Muslima, who did not wear a hijab at the time of the interview, said:

“… The argument is of course that a headscarf is mandatory, uh … I also understand that completely, but to call it really mandatory, I do not know … I think clothing is much more important, I mean, you can wear a headscarf and then tight jeans, but I will not agree it’s completely modest, I find a tight ass jeans sexier than hair, so I think it is important to perhaps pay more attention to that, but then again, I think that everyone finds their own way in it … but in the Netherlands the consciousness of Muslims has grown …”(Annette, 28, Converted Muslima)

Another participant, a born Muslima, who now covers her hair, refers to the hijab as a religious symbol, whose wearers represent something:

“Covering your head is not just putting on a nice headscarf, it’s not a fashionable accessory—although it’s sometimes treated this way. Rather, it’s something that defines behavior. I, when I started wearing a headscarf, also began to behave differently, I started to dress more modestly, but it does not mean that I really became more modest, and less attention-grabbing. This is a personal feeling. Not everyone will agree with me. But in my view, this cover should symbolize protection and a lack of prominence, but this is not always the case.

In the Netherlands, as a Muslima you are more noticeable once you wear it. Everyone now knows you are a Muslim … and also, you will not get any attention from Dutch men on the street … no one will dare to ask you for your phone number … but it is not true that you are no longer prominent when you put the cover, in fact, you stand out for both groups of people, and you represent something … and for me it also has another meaning: ‘I want you to let me be who I am … Why do not people accept me as I am?’”(Kadisha, 26 years old)

The clothing of a Muslim then, seen through the lens of Islam and the current Western mode of dress could be viewed as coming from opposite perspectives. The stories of converted Muslima’s who were once attached to the Western mode of dress and who are now embracing the Islamic clothing mode emphasize this interesting point. Like Boulanouar argued: “All efforts at beautification and adornment are undertaken inside the home for the benefit of yourself and your family and loved ones; all efforts at coverage and modesty are for outside the home, and for the unsanctioned gaze of passers-by or anyone who comes into ‘your space’” (Boulanouar 2006, p. 154).

3.2. Building Identity through Style

“There is no one who says to me: ‘You have to take [the headscarf] off.’ My parents ask me to take it off and are afraid that I will not find a boyfriend or a husband when I wear a niqab. But to tell you the truth, I prefer not to find anyone. [I prefer] to be myself, with my niqab … and if a man cannot handle it, then I’ll be alone until I know someone that will accept me as I am …”(Asia, 22 years old)

The quote above is from a young woman from a Moroccan background who has rediscovered Islam and practices Islam differently than her parents. She changes her Islamic dress from a niqab (face veil) to a khimar (long hijab where only the face remains visible), this in spite of her parent’s disapproval. Van der Veer argues that the wearing of headscarves by Muslim women “is regarded as a total rejection of the Dutch way of life” (Van der Veer 1996, 2006). Another angle to look at this is analyzing the racial, phenotypical question of ‘Europeanness’, as in the case of native Dutch converted Muslimas. What happens if a blonde, blue-eyed Dutch woman decides to wear a headscarf? Does she confuse her peers as she passes through different identities and notions of belonging when she is Dutch and Muslim, yet not born into Islam? How are women like her changing the concept of ‘whiteness’ in a Christian-based society? (Essed and Trienekens 2008; Wekker 2016).

Romania proves an appealing case study regarding this question. Stoica argues that in the Romanian city where she conducted her ethnography, as there is no Islamic clothing available there, converts need to put together outfits by making use of what is locally available and accessible, combining various items of clothing in order to produce an overall modest appearance (Stoica 2013). In order to develop a suitable modest Islamic look, Muslim converts actively search for reliable sources of information and are continuously scrutinizing themselves and other Muslims (Stoica 2013). This can remind us of times where converted Muslimas choice of fashion was dependent on what was sold in the mosque or at the local tailor of a multi-cultural neighborhood in one of the bigger cities in the Netherlands (Hass 2011; Hass and Lutek 2018; Vroon 2007, 2014), unlike the present time, when more styles of Islamic clothing are available for purchase and ordering clothing online from all parts of the world has become a common practice. Furthermore, Stoica states that for Romanian converts, the biggest challenge they faced was to avoid the high degree of unwanted attention they experienced when wearing the hijab in public spaces. They feel that they are continuously in the spotlight and have to develop ways of responding to the reactions their styles of dress evoke: (Stoica 2013) in other words, always needing to justify their choices.

In the second half of the 20th century, marginalized groups such as women fought against the injustices that were practiced against them and built political movements in the foundations of their commonalities and shared experiences to work against injustice. They used identity politics as an organizing mode to transform stigmas and to fight for recognition within society. Here, identity politics aims to reclaim or transform previously stigmatized perceptions offered by a dominant culture (Crenshaw 1991; Vader 2011; Yuval-Davis 2006a, 2006b).

Identity politics is of relevance when discussing the position of Muslim women in Dutch society, since it can be used by Muslim women to challenge the image that is created of them. Dutch society often still perceives Muslim women as passive victims in need of rescue. Through the use of the politics of identity, Muslim women can use action to make themselves visible within society, and to create a public identity that moves beyond the stereotypes of a Muslim woman in a non-Muslim context.

Here, we focus on one pointed example: on 26 May 2010, the Dutch newspaper the Telegraaf published an article titled: ‘Muslim women defend themselves by being “Really Dutch”. “Echt Nederlands/Really Dutch” was a campaign released by the Muslim women’s organization Al Nisa, through which they fought against prejudices regarding Muslim women (see Appendix A). With this campaign, Al Nisa helped start a conversation around the public identity of Muslim women in the Netherlands, one that moves beyond the common prejudices and stereotypes of Muslim women in Dutch society.

The responses to the “Real Dutch” campaign were varied: some loved the idea, but also others claimed that “such women do not exist” or that “a real Dutch Muslim wouldn’t wear a headscarf” (Hass and Lutek 2018; Vader 2011). Yet, these posters have given Muslim women a face, showed variety in Dutch Muslim women (all four women come from diverse cultural backgrounds), and have given Muslim women in general a voice in the debate, something that usually had been absent. In one of the posters, a woman wears a hijab with a Dutch pattern and in the colors of the Dutch flag. The Dutch flag, a symbol of nationhood, and the hijab, a symbol of Muslim culture, are not only combined, but also made into one: the binary between the two disappears. In another poster, a Dutch looking girl who has no symbols of Muslim culture, such as a hijab, states she is going to the mosque, thus obviously being religious, but being religious not in a stereotyped way. She presents that she can be a practicing Muslim while keeping her appearance as she wishes. The posters, including two born Muslims and one converted Muslim, help to create a public identity for Muslim women that moves beyond the stereotypes, and beyond the image of Muslim women as passive and suppressed by their culture and religion. It presents women who have the capability to create their own identity, showing that they are able to take part in the debate about immigration and integration, and can show their own critique of Dutch politics (Vader 2011). They show that being Dutch and being Muslim is mutually inclusive rather than irreconcilable, because it is the Dutch inside the Muslima, and the Muslima inside the Dutch that can make all of this possible.

“My religion is my identity”(Asia, 22 years old)

Bartels shows how adopting an Islamic identity, which includes a choice to cover the head, is what helps young women who feel disinterested in the Netherlands to nonetheless fit in (Bartels 2005). A young woman who wears a headscarf and anchors this act with the words “this is my own personal choice” fits in Dutch society as an independent woman, free to choose her own way of life, detached from the group context of the broader ethnic community of which she is a part. Academic research shows that parents and family members encourage their daughters to continue to study, as long as they are religious and live according to Islam. They are seen as acquiring an education and are building their (professional) future. Yet, at the same time, prominent Muslim women are also not always accepted entirely in society: people sometimes distance themselves from them or ask them to make changes about themselves.

This reality is well explained by Kadisha, who remarks that being Muslim in her professional education environment proves a daily challenge, and limits her from feeling free to be herself:

“I see that in college, people see me and think, ‘Oh, she has a hijab … We should take some distance [from her].’ People do not talk to me about certain subjects … and this is very bad for me … You do not have to censor yourself with me … You can talk to me about almost everything … it makes me sad that people associate me with all these stereotypes … And because of these reactions it is hard for me to be completely myself …”.(Kadisha, 26 years old)

Veiling is a condensed symbol of embodying Islam and taking on a visible marker, making it clear for anyone to see that this female is a Muslim, and thus means publicly declaring a new identity. For many female converts, the stage of donning the hijab is a stage of “coming out” (Van Nieuwkerk 2014). It is a stage that marks them as the ‘other’, someone who is not completely/no longer Dutch/European, even though such a binary is problematic in the first place (Hass 2011), and it is often hard for the family to accept. Some converts found a solution by putting on an African-style head covering, instead of the hijab (Badran 2006; Badran 2013). After starting to wear the visible marker such as the hijab, many female converts feel two major changes in the way they are treated (Van Nieuwkerk 2014). At times, they are considered less intelligent and are perceived as strangers (Hass 2011; Hass and Lutek 2018; Van Nieuwkerk 2014) and therefore some have faced discrimination in the job market and in other societal institutions. The hijab is perceived as the most visible symptom of female degradation by non-Muslims, a condition that marks the World of Islam, but is, problematically perceived, as alien to the West (Van Nieuwkerk 2014). For many converts, becoming Muslim eventually entails changing many aspects of daily life and cultural practices that might conflict with their social environment. Galonnier shows how ‘white’ converts to Islam are anomalous individuals in a world where race and faith have become closely intertwined. She argues that while they disrupt classic understandings of whiteness and enter a setting, the Muslim community, where whiteness is neither unmarked nor dominant, white converts to Islam can be characterized as “non-normative whites.”

This is further proven by the fact that, just like their non-white sisters, white Muslims wear all Islamic styles, ranging from modest “Western Clothing” with a hijab or without, to niqabs and burqas, and everything in between. By altering their whiteness in such a visual manner, white converts to Islam develop a form of reflexivity that sheds light on the underlying assumptions attached to white skin in America and Europe (Galonnier 2015a, 2015b). In this regard, another study shows that in the USA, many argue that to understand Muslims, we must move our analysis “beyond black and white.” Husain argues that black and white Muslims are positioned as either black/white or as Muslim. This suggests that ‘Muslimness’ and religion more generally, shapes the construction of blackness and whiteness (Husain 2017).

Here, we see the core tension mentioned earlier, and through Islamic fashion, we see a modification and challenge to ‘whiteness’ in majority-Christian civil society, as Hass and Lutek have earlier argued (Hass and Lutek 2018).

Identity search, reflections on identity, critique on identity and the desire to shape a unique identity can be seen as another example of the agency of social actors in social interaction. Current literature and ethnography show rejection and acceptance of identities, which occurs simultaneously. This has been shown above, where interviewed women experience a simultaneous rejection in the Netherlands and in their countries of origin. In one, they are too Muslim, while in the other, too Dutch. Here, we see the painful intricacies of identity:

“… As a white woman, as a Muslim who has experienced multiple identities and also Islamophobic discourse in the media, I can talk back against a lot of these Islamophobic discourses … I did notice that in the beginning of my thesis, that I focused a lot on the gender aspect, but I became more aware of the race aspect … I was not so concerned with race before, but as a white Muslim you become aware of certain racial aspects and inequalities in terms of Islamophobia … and also in resistance and certain privileges …”(Marja, 37 years old, converted Muslima)

In the discourse about identity, we can see the racialization of Islam and the self-reference of converted Muslims as “white” Muslims. Golonnier and Husain argue that white converts to Islam develop a form of reflexivity that sheds light on the underlying assumptions attached to white skin in America and Europe (Galonnier 2015a, 2015b; Husain 2017). Regarding the certain privileges seen in the above quote by one of the participants in this study, Moosavi argues that upon converting to Islam, white converts’ whiteness is jeopardized, thus showing the precariousness of whiteness. Converts’ whiteness can cause them difficulties rather than benefits due to the unique context that they find themselves in. Unlike racist white supremacists, who portray white people as always the victims, this paper seeks a more balanced understanding of the complexity of whiteness as often but not always privileging (Moosavi 2011, 2015). Similar to Moosavi’s argument that whiteness is not always privileging, we will discuss a quote from a converted Muslima, who reflected on the days she was single and wanted to be introduced to a Muslim man:

“in this respect, I often have the feeling that I really do not belong anywhere anymore. I do not belong in the Moroccan community or the Turkish community … or whatever … because to them I am really Dutch … but I also no longer belong to the Dutch community, because then now I am a Muslim.”(Lydia, 36 years old, converted Muslima)

3.3. Agency

“… The desire to ‘free’ us from the hijab, to free us from Islam, is in my eyes oppression, because it implies that we are not mature enough or wise to choose what we think best …”(Asia, 22 years old)

There are no statistics kept about the rate of conversion to Islam in the Netherlands, since one does not have to register to convert, and one could convert in the privacy of their home. This is in contradiction to conversion to Judaism, which is documented through the synagogue and the specific Jewish community. In the Netherlands, practicing one’s religion is considered a private matter, so often religious affiliation is not documented. However, it is widely accepted that in Islam, there are more female converts than male (see more in (Vroon 2014)). The prominent incongruity between the larger numbers of female converts among a population that often considers Islam to be particularly ‘oppressive’ to women makes this a topic worthy of research because it teaches us something about gender, religion and agency in conservative religions.

The question to be asked here is what gender norms in Dutch society are these women either rejecting completely or modifying? Scholars of religious piety such as Saba Mahmood, and scholars of religious conversion to Islam in the West, such as Anne Sophie Roald and Anna Manson McGinty, found that women embraced non-liberal religious identities not just due to piety but also as rejections of other social models (Avishai 2008; Fader 2009; Mahmood 2001; Marranci 2008; Roald 2004, 2012). One possible rejection of a social model could be the concept of ‘whiteness’ in a Christian based society. Is the concept of ‘whiteness’ applicable to the Netherlands and mainland Europe (Essed and Trienekens 2008; Essed 2001)? Why have these women chosen a religion that is often portrayed in the media and among peers as regressive, both politically and philosophically, and especially concerning women’s rights? Muslim women in the West, including in the Netherlands, are regularly perceived as being oppressed (Abu-Lughod 2002; Vroon 2007, 2014). They are often portrayed as objects, rather than as actors capable of using Islam as a source of empowerment and agency (Abu-Lughod 2002; Vroon 2007) Following Ortner (Ortner 2006) and Vroon (Vroon 2007), we would describe agency as “how actors formulate needs and desires, plans and schemes, modes of working in and on the world.” For a lot of women, the choice to embrace a conservative religion is a way of finding peace and coming home. This has been shown in literature as being true for converts to Islam, and for converts turning to Orthodox models in Judaism (Benor 2012; Davidman 1991; Van Nieuwkerk 2014; Vroon 2014). Furthermore, another possible answer is that while some women may experience conservative religions as restricting, they are also liberated and empowered by their religion (Avishai 2008; Mahmood 2001).

The following quote from a participant in our study emphasizes that it is sometimes hard for family and peers to comprehend why a Dutch converted Muslima chose to cover her hair. It is often perceived as being an action that her (Muslim) spouse made her do. This example is of a woman who, to the surprise of her family, did not take of the headscarf even after she got divorced, an example of how this woman is “formulating her needs and desires, plans and schemes, modes of working in and on the world” (Ortner 2006).

“… and now that I am divorced, I also heard comments [such as]: “We were wondering when you would finally take off the headscarf … Then I think: wow, then you really have drastically misunderstood something … I have worn the headscarf for no one but for myself. And even if I would have been divorced for a hundred years, [the headscarf] will stay on as long as I stand behind it. So yes … he did not understand that (laughs) …”(Lydia, 36 years old, converted Muslima)

Bartels shows how adopting an Islamic identity, which includes a choice to cover the head, is what helps young women who feel disinterested in the Netherlands to nonetheless fit in (Bartels 2005). A young woman who wears a headscarf and anchors this act with the words “this is my own personal choice” fits in Dutch society as an independent woman, free to choose her own way of life, detached from the group context of the broader ethnic community of which she is a part. Ethnography shows that parents and family members encourage their daughters to continue to study, and, as long as they are religious and live according to Islam, there is no reason to worry that they will deviate from the right path. On the contrary, they acquire education and are building their (professional) future. Yet at the same time, prominent Muslim women are also not always accepted entirely in society: people sometimes take a distance from them or ask them to make changes about themselves. Some Muslim women take the decision to veil, to show the society that they are Muslim, part of the global Muslim Ummah.

Remy converted to Islam two years ago, she is currently a student at one of the universities in the Netherlands. This semester, she is also wearing a headscarf. Her headscarf does not necessarily look like a (traditional) hijab, but rather as an African headcover (Badran 2013) and could easily be assumed by people passing by her in the streets that she chooses this as a fashion statement, since one could not necessarily tell she is a Muslim.

“… (I starting wearing it) … to show people that I am a Muslim. You have to wear this in front of men who are strangers to you. I buy them in Amsterdam. In the [redacted] street. I get my inspiration from the Egyptian YouTuber Dina Tokyo. In one of her videos, she shows 25 ways to tie a turban …”(Remy, 22 years old, converted Muslima)

We will look into the story of Evelien, also a 22-year-old woman, who converted to Islam at age 17 and who is active on social media (as a blogger and vlogger on Instagram and YouTube), as well as on Dutch television and (online) newspapers and in her local Muslim community, as an active participant in her mosque. As Evelien explains it, she not only feels like coming home and finding peace after embracing Islam, she acquired a sense of belonging. Evelien covers her body almost completely, and only her face can still be seen. As she explains:

“My ass attracts more attention than my hair (laughs), so I decided to completely cover myself.”(Evelien, 22 years old, converted Muslima)

Most of the Muslim women had a period during which they did not wear a hijab, or at some point in their lives decided to give up wearing it. Dutch women who converted to Islam admit that before they converted to Islam, they also had negative perceptions of women covering their heads. They saw the hijab as inappropriate for all the stereotypes mentioned above: uneducated, uninspired, and submissive to the men in their family. This was evident in other ethnographies in the Netherlands as well (Bartels 2005; Van Nieuwkerk 2014; Vroon 2014). Here, we see that the wearing of the hijab reflects deeply personal decisions that can, in a Western context such as the Netherlands, work to actively mark a Muslima as living outside the expected norms of Western society. Yet for many Muslim women, who view their hijab as a divine command, a great incentive to wear the hijab is the recognition that this demarcation provides, insofar as everyone who wears it is shown as a Muslim and belonging to the Muslim nation. Some women also view the wearing of the headscarf as resistance to Dutch society, which does not always allow them to feel part of the national fold. Thus, it is a way to say: “you don’t accept me as fully Dutch, I will show you through my visual symbol that I am indeed not Dutch” (Hass and Lutek 2018).

“Putting on this head cover is on one side to identify with the Muslim community, and on the other hand, is a statement to wider society, to inform everyone that I am a Muslim …”(Yasmin, 25 years old)

In the ethnography, it was evident that the reason that second-generation women in the Netherlands wear the hijab, beyond the desire to follow Islamic law and divert undesirable male attention, is also to express themselves and their religious identity. Here, we see the breaking down of the dichotomy between Western/Eastern society, where women living in a Western country actively incorporate styles and fashions too often labelled as foreign into their daily lives. In this way, they integrate Western and Eastern perspectives together, and destroy the often-assumed binary between the two. For this reason, Vroon notes that the hijab and other coverings are significant for the agency of women who choose to cover (Vroon 2014). The choice is not easy, because sometimes women cannot wear the hijab in some places of work. Individuals who wish to show their commitment to their religious community sometimes encounter negative sanctions, such as expulsion from the school (see more: (Bowen 2007; Scott 2009)) termination of employment, or social mockery, because there are religious symbols (such as head covering) that highlight the differences between the minority group and the dominant group. Women are assumed to cover due to male pressure in their families, which may sometimes be the cause, but this is not always true. As this study argues and has shown, many women consciously choose to dress in Islamic style more prominently than their mothers do, and more than their families would like, a point that can suggest quite a bit about these women’s agency (Moors 2009, 2013; Tarlo and Moors 2013; Vroon 2014).

“Until you accept me as I am, I will continue to be in all the ways I can be myself. In my opinion, covering up is a very important part of my faith. Look, I do not do everything exactly according to the Islamic religious law, but I do try to do it clearly. Unfortunately, this is not always possible in Western lifestyle.”(Myriam, 25 years old)

This quote also shows the extent of the agency as the ability to choose and act in social action and could show an element of resistance in some cases, depending on context. The interviewee feels her society limits her ability to be who she is, and therefore her head covering reflects a great deal of identity building, of the inner individual that drives her to social action (Ortner 2006). Put differently, the hijab and Islamic dress (whether it is a hijab alone, or an overcoat with hijab) is not only an alternative fashion statement to what fashion is in the West, but also an identity builder itself (Tarlo and Moors 2013).

Additionally, some Muslim women express criticism of Muslim societies and view them as too traditional (Morocco) and criticize the conduct of countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran and Afghanistan. In the next quotes, we will see references to the country of origin of the parents as home, but a home that does not allow them to be themselves:

“In my country they do not let me be as Muslim as I want, [as they are] gossiping about me walking down the street with black veils …”(Asia, 22 years old)

Some women see the Netherlands as the place that allows them to be themselves:

“… Here in the Netherlands they allow me to be more of myself, despite the looks I get and racism. However, it is okay because they are not Muslims … but when a Muslim behaves to you in a way that is not nice because you want to wear something, no matter whether it is a mini skirt or a hijab, ghimar … that hurts …”(Jamila, 30 years old)

3.4. Agency, Dress, and Cover

In the previous sections, we argued how agency is embodied in these women’s lives and how identity is constructed. The current section will take a closer look at the issue of modest dress and covering, and how it is in fact a religious commandment. This thinking starts with the following quote taken directly from the Quran:

“Tell the believing men that they shall subdue their eyes (and not stare at the women), and to maintain their chastity. This is purer for them. GOD is fully cognizant of everything they do”(Quran, Sura 24: 30)

Even though religion and religious practice is considered a private matter, head coverings and hijabs, especially face veils, such as the burka and niqab, take the most public attention in the Netherlands. On the one hand, there is a demand to prohibit this kind of clothing, because it is considered to endanger the public (it is impossible to see who is under it), and is said to cause social unpleasantness when one does not see the face of the person opposite. It is also popularly perceived, based on the lived experience of interviewees we encountered, that these (face) veils are alien to Dutch society. In the current situation, there is agreement that there are cases in which a woman will not be able to cover her face: if she works in public service, provides service in a public setting and in cases where she needs to identify herself.

The Netherlands has approved a ban on wearing “face-covering clothing” including the burqa and niqab in some public settings. The limited prohibition will not block wearing of the hijab, which only covers a woman’s hair. It applies on public transport and in education institutions, health institutions such as hospitals and government buildings. The ban also covers other full-face covers such as ski masks and full-face helmets.

The former mayor of Amsterdam, Job Cohen, stated in 2008 that face-covered women would not receive unemployment benefits on the assumption that their unemployment was a direct result of the form of cover that makes it difficult to find work outside the Islamic context. The burkas and the various facial coverings are in a minority in Dutch society, but the issue is always reaching the headlines, likely because of the mismatch between this item of clothing and popular conceptions of Western life in a country such as the Netherlands. Yet, we cannot dismiss how, for the women interviewed, this clothing helps to build identity.

For the women who decide to embrace a Muslim lifestyle and identity, the hijab is a form of freedom and is not oppressive. As interviewee Fatima explained: “In my headscarf I have my freedom.” Thus, they argue that through the hijab they can feel that they are watching, and not just being watched. Muslim women have the feeling that the hijab frees them from the patterns of fashion and frees them from the myths of consumerist conceptions of beauty in Western society. Covering is a means of preventing sexual harassment, allowing women to go outside, work, and even allowing them to travel around areas where a woman without a hijab would not feel comfortable moving around. Covering is a means of gaining respect and elevation. Most importantly, covering is also a divine demand. Therefore, a Muslim woman who made the choice to wear a head cover does not need to be released, because she is already free. On the contrary, even more insulting to these women are the Western perceptions of “liberating women from their headscarves and the depressing patterns of Islam.” This idea arose in the conducted interviews:

“… I used to watch documentaries on television about women wearing headscarves, and they would say, ‘I’m very conscious of myself and my headscarf.’ And I always thought to myself: ‘what is she talking about?’ I was very naive and thought that they would accept me anyway, even if I wore a headscarf … But as I got older, I became very conscious of my choice to wear a long hijab, because it is a choice, a choice with many implications. Because you are treated differently, you are asked different questions, for example if someone without a head covering will talk to me differently from you because I wear a hijab. I’m an open person, just some people do not see it on the outside …”(Fatima, 23 years old)

3.5. Islamic Dress as Boundary Work

“Say to the believing women that: they should cast down their glances and guard their private parts (by being chaste) … and not display their beauty except what is apparent, and they should place their khumur over their bosoms …”(Quran, chapter 24, verse 30)

Scholars of religion argue that the religious women they have studied are doing boundary work, whether its Muslim business women in the Netherlands or Muslim women in the USA (Bartkowski and Read 2003; Essers and Benschop 2009). In general, religious actors are capable of using the repertoire of their faith traditions in strategic, creative and sometimes subversive ways to meet the practical demands of everyday life (Bartkowski and Read 2003a; Mahmood 2001). Sandiki et al. demonstrate that contemporary urban Muslim women navigate the boundaries of fashion and faith through their espousal of religion as a legitimate and alternative form of modernity (Sandikci and Ger 2009, 2011). Sandiki et al., similar to Miller, find cloth being used as an expression of interconnectivity of categories such as politics and religion, modernity and religion, rather than a separation of these categories (Bartkowski and Read 2003a; Miller and Küchler 2005; Sandikci and Ger 2009, 2011). For a lot of women seen in different ethnographies, there is no contradiction between the espousal of fashion and having collections of scarves used for veiling, overcoats and other Islamic dress that the mass market makes possible (Hass 2011a; Hass and Lutek 2018; Sandikci and Ger 2009, 2011; Van Nieuwkerk 2014; Vroon 2014). It is often claimed that women who are part of religious subcultures engage in boundary work that distinguishes them from mainstream values. They construct distinctive identities that selectively appropriate values from the cultural mainstream. In the case of Bartkowski and Read, that would be from mainstream American culture (Bartkowski and Read 2003a). In the European context, we would be talking about distinguishing from mainstream Dutch culture and mainstream Dutch values (Badran 2006; Essers and Benschop 2009; Hass 2011; Hass and Lutek 2018; Vader 2011; Van Nieuwkerk 2014; Vroon 2014).

Essers and Benschop add to this view with their findings of how Muslim female entrepreneurs of Moroccan and Turkish origin in the Netherlands construct their ethnic, gender and entrepreneurial identities in relation to their Muslim identity and as doing such they gain agency at the crossroads of gender, ethnicity and religion (Essers and Benschop 2009b). In addition, the hijab clearly marks Muslim women who wear it, and places unveiled Muslim women in the position of explaining why they do not (Bartkowski and Read 2003a; Mernissi 1987, 1991). The practice of veiling identifies a Muslim woman not just by her religious affiliation and gender convictions, but also underscores her distinctive ethnic and national identities (Bartkowski and Read 2003a; Essers and Benschop 2009b; Vroon 2014).

For these women, neither the accessibility nor availability of the dress is a problem, but rather how to conform to the commandment to be modest and avert the male gaze, while simultaneously embodying the Islamic commands of beauty and order. As Sandiki et al. show, the work of ‘interpretation’ is simultaneously verbal and material. They argue that these women can explain what they are doing and how it relates to their struggle to understand and interpret Quranic demands, but the most eloquent testimony is in their practice, what is termed their ‘beauty work:’ the interpretation constructed from the richness of practice that is often much more nuanced than anything they can say about their relationship to religious texts (Sandikci and Ger 2009, 2011). While an outsider might see a contradiction between the assumed materialism of mass consumption and religious spirituality, insiders argue the provision of new forms and materials is God’s blessing that enables them to resolve contradiction and allows them to act on cosmological imperatives.

Appadurai (Appadurai 1986) argued that desire and wish are the basis for the circulations of goods, commodities, and determining their value, since commodities can be defined as objects of economic value. The desire for luxury and the achievement of distant or exotic objects (such as authentic overcoats made in Turkey, or hijabs from cotton and luxury textiles from far away) is what drives the wheel of the capitalist trading since these goods are sold all over the world, whether in Muslim style clothing shops found in the streets of London, Paris, or Amsterdam, or online (Hass and Lutek 2018; Tarlo and Moors 2013; Van Nieuwkerk 2014; Vroon 2014). Appadurai explains that new cultural demands are accelerating new economies, and therefore the objects themselves should be treated as informants that provide the anthropologist with knowledge of the world, instead of relating to the object as anchoring the systems that created it (Appadurai 1986).

The Islamic dress in this example encapsulates the political that enables its existence, the social that determines it as merchandise (and not as a worthless object to be discarded) and gives it a monetary, aesthetic and moral value (the rarer the textile is, the more expensive the clothing will be). In addition, the overcoat or the hijab as an object is able to tell us a story: a story of nostalgia (the desire to wear a Turkish grandma-style overcoat, rather than the denim trenchcoated-style), a story of immigration, integration into a new society, and what it means to be a newcomer to a community, a story of conversion (to another religious group), a story of change (change of clothing due to conversion, or due to migration) and a story of roots elsewhere and a generational gap (on one hand trying to distance themselves from cultural customs by claiming a pure Islam, disassociated of cultural influences, while on the other hand being proud of one’s Bangladeshi or Turkish roots). This especially becomes stronger for some women when they chose the traditional ‘grandma’ overcoat over the modern interpretations’ some young (Muslim and non-Muslim) designers have regarding this specific Islamic dress.

When talking about clothes and objects being exported and imported, such as the Turkish overcoat travelling from Istanbul to Amsterdam (Ünal 2013), it is helpful to look at Elor’s work on the Soul of the Biblical Sandal (El Or 2012). Elor stresses that objects of travelers allow them to imagine themselves as nomads and thus allows them to be disconnected from infrastructures and institutions. As she argues, it is a way of spreading (old) stories about ourselves and sewing other stories underneath them. The Turkish migrant women brought the overcoat with them to the Netherlands in the 1970s, and this piece of clothing tells us a story. On the other hand, Islamic fashion itself also has influences from travelers, for example, the military influences the overcoat experienced when it became more tailored and dressier. The overcoat, as well as the hijab (worn together or separately), build an identity that is foremost a Muslim identity, yet also a global Muslim identity, hinting at the global character of the Islamic Ummah, since this choice of clothing entails a Muslim identity that exists in a pluralist society (in our case in the Netherlands). Tarlo states that clothing can hide identity and can reflect identity and cultural fidelity (Tarlo 1996). As she sees it, clothes have a unique and unusual role in the perception of an identity that depends on the person who wears them, as she explains in the context of identity shaping in contemporary India. Thus, the ability to store the object and pass it from one generation to the next is to challenge existing reality, to disconnect and declare, “I am not from here,” but also to reflect loyalty and belonging to the culture of origin and testify “I am from there.” The following quotes demonstrate this:

“Look, here in the Netherlands they will always see me as a Moroccan, a Muslim, with a hijab. I do not really belong … But when you are there, you are treated as Dutch because you live in the Netherlands … and they are right … I am really Dutch, I was born here … My Dutch is much better than my Arabic. But what annoys me is that everyone here thinks that life here in Holland is perfect … that it is the land of opportunity, you are allowed to work here, to make money … it is true … but people do not really know much about it. It’s true, you learn, you work, you get somewhere in your life, but they do not know what it’s like to live with the feeling that you do not really belong to the place …”(Selma, 25 years old)

“[I was told by a Dutch person:] ‘when you put on a head scarf, you put on a symbol of oppression, and you have no ability to express yourself and your opinions.’ Then after [this person] saw a Dutch woman in a very Western-style, fashionable dress, and she thought she was freer and more individualistic than I was …”(Fatima, 23 years old)

Despite these stereotypes, many women feel less objectified and less oppressed when dressing modestly. Dutch Muslims, especially those new to Islam, are convinced that there is an egalitarian relationship between men and women in Islam and society as a whole. Educated in the Netherlands, the young women emphasize the equality of opportunities between men and women, and they sharpen it, while giving examples of pure Islam, which is not influenced by cultural practices, such as the primary Islam of the Prophet Muhammad. Women do not see themselves as oppressed, and on the contrary, they perceive themselves as liberated and equal to their partners and other men in society.

3.6. The Aesthetic of Covering

“At that moment their eyes were opened, and they suddenly felt shame at their nakedness. So, they sewed fig leaves together to cover themselves.”(Genesis 3: 7)

Moors brings a convenient starting point of discussing the fashion–Islam nexus, through the eight-page article ‘Hip with the Headscarf’ which appeared in the 1999 weekend edition of an upscale Dutch daily, De Volkskrant magazine. This article started with the observation that “more and more women with headscarves wear fashionable styles of dress and lots of makeup” (Moors 2013). Next to portraying a number of young women wearing such fashionable styles, the article also presented the points of view of expert commentators. Some, such as a Moroccan Dutch politician for the Dutch Labor Party, who wears a headscarf herself, emphasized the growing self-confidence of these young women. Including herself in the category, she commented: “We are really stylish, we read Cosmopolitan and buy our clothing at H&M …” She also commented, “Young Muslim women develop their own style, hip and attractive … they have guts…and they are saying ‘I wear a headscarf because I am a Muslim, but I am living in the Netherlands’ (Tarlo and Moors 2013; Moors 2013).

Here, it is important to remember that, while in the Netherlands (as elsewhere), a shift towards more fashionable Islamic dress has occurred in the course of the last decade, a small number of women have adopted abayas, khimar and similar styles of covered dress that are sober and distinctively non-fashionable, and may even be in some cases considered anti-fashion since these women distance themselves from the highly fashionable layered styles of mixing and matching mainstream items, and from the highly fashionable abayas that have emerged in the Gulf states. Labelling their styles simply as anti-fashion does not do justice to the complexities of their position. They do criticize fashionable Islamic dressing styles with theological reasoning, but in spite of their long, dark-colored covering, they simultaneously talk extensively about the beauty of such forms of covering, that includes the feel of the fabric and the feel of the cut and thus not only the visual register. These approaches enable them to wear a broad range of styles underneath, including highly fashionable styles, but they choose who to reveal those styles to (husbands, family and female friends) and some do enjoy the range of possibilities these covers provide them with. The following participant, who wore a long hijab and modest wide clothing, states that after wearing Islamic clothing, she does not feel like she is part of the Dutch national fold:

“… I am still Dutch, but I am actually no longer Dutch … I am no longer a member … I am no longer a member of Dutch culture. I have my own little subculture. I was a bit shocked recently that a lot of girls were converting, but as a sort of a resistance subculture … which was punk culture a few years ago. As a kind of transgression against society … and then you look for the ‘worst thing’ and that is apparently Islam right now …”

She then addresses the Niqab as a specific Islamic clothing that she personally would not think of wearing:

“… so then you just walk around with a Niqab at 16, 17, 18 years old, and say that you are converted … and that are you actually the punker from ten years ago … and some of them have zero knowledge, really nothing at all and they ask me why I don’t wear a niqab … in my head I answer: ‘and why do you actually wear one?’ You don’t even know how to do Dauwa, it turned out later. That really shocked me … I feel that if I dress like that, then I have to live by it. I think that’s somehow hypocritical in my eyes [to do otherwise] … I have to earn that somehow. If you then suddenly wear a niqab with zero knowledge, but then, for example, sit outside in the dark with your girlfriend in the pitch dark or go and get groceries after nine in the evening, with a niqab, then I think, then you have not yet fully understood something. I see it last quite often. Indeed, it is often very young girls who convert and immediately wear khimar or immediately wear niqab. Personally, I think that’s just a piece of clothing”.(Lydia, 36. Converted Muslima)

Thus, Western perceptions and representations of veiled Muslim women are not always simply about Muslim women themselves. Rather than representing Muslim women, these images fulfil a different function: they provide the negative mirror in which Western constructions of identity and gender can be positively reflected. It is by means of the projection of gender oppression onto Islam, and its naturalization to the bodies of veiled women, that such mirroring takes place. Al-Saji argues that this constitutes a form of racialization (Al-Saji 2010).

4. Hashtag #Modesty

One Saturday morning, the first author opened the Dutch ELLE issue for February 2018. While she browsed the pages with this spring’s colors and most fashionable must haves, she came across an interesting article by Raja Felgata, a Dutch Moroccan journalist, blogger and founder of The Colorful 100 (in Dutch de Kleurrijke 100), a project emphasizing the cultural diversity in the Netherlands. Felgata appeared on Dutch television, wrote columns and is an Instagram blogger. Her article in Elle introduced six very fashionable Dutch Muslim women who all had one thing in common: they wanted to feel fashionable while staying true to their religious and cultural background. This meant for some being hip with the hijab, while for others (who did not cover their hair) this meant wearing modest fashionable dress. Modesty was also different for each of the Instagram personas: some showed non-revealing long loose-fitting clothing, others had Instagram accounts with tight clothes and pants, but nothing revealing, others had off-the-shoulder dresses and shirts, yet still considered modest, because of their wideness and long textiles. Some of the women claimed they started blogging because they felt a lack of representation among white models dressed in (Western) clothing that they as Muslims would never choose, so they wanted to create Instagram accounts for women with their cultural and religious background. Others stated they opened their accounts because they love fashion. One woman claimed her Instagram account is one stepping-stone in showing the world that the (Dutch) Muslim woman is not oppressed, like media and some politicians would like us to believe. Some women had a very professional Instagram profile with only professional pictures, while others revealed their everyday life as a Dutch Muslim woman, mother, spouse, employee and fashionista. All had in common the hashtags about modest clothing, that provided them with many followers. This ELLE article is a summary of this work. It showed in two pages the diversity of Dutch women (Moroccan, Ganesa, Turkish, Afghan and a converted Dutch Muslima), some who have been chosen to present famous brands such as Dolce and Gabbana. These women have key important messages for other women: fashion is global, modest clothing can be beautiful, the hijab (which is their own personal choice) can be a fashionable accessory, and the fashion industry should include more diversity.

One of the participants in this study is a successful Instagram blogger and vlogger, as well as a persona on Dutch television and in (online) newspapers in her local Muslim community and, lastly, an active participant in her mosque. We will call her R (a pseudonym). She is a Dutch Muslima, who converted to Islam a few years ago. Her stage of “coming out” (Van Nieuwkerk 2014) contained not only the wearing of a head cover in her everyday life, thus showing everyone that she is a Muslim now, but also coming out through social media (Instagram, Facebook and Twitter) and through more traditional channels of media (television programs and documentary films).

We argue that her Instagram profile stands out from many others: the first reason being it is connected directly to her Islamic dress. While other Dutch Muslima’s blog about modest fashion and the beauty of cover, or as what Moors would call the aesthetic of covering (Moors 2013), most are dressed in a ‘Western’ dress style, wearing the modest exemplars of Western brands such as H&M, Zara, Mango, COS or Massimo Dutti, as well as the more expensive and exclusive brands such as Vivienne Westwood or even Versace, some with a hijab, others without, but primarily hash-tagging with #modest fashion. Yet R uploads mostly photographs of herself in long robes and Islamic dress, often khimars in all kinds of different colors. Another reason is linked to the personal messages she sends her followers, while she shares the challenges of life in a text under her pictures. According to her, that is one of the reasons why she has many followers.

“… There are not many Muslim women with a headscarf and a long dress who post photos online … My biggest message to my followers is that nobody is perfect, even though it sometimes it appears like that on social media …”(R, Dutch converted Muslima, 25 years old)

Her pictures and posts contain the hashtags #hijab, #muslima, #modest, #modesty, #modestclothing, #Islam, #modestfashion, #modeststreetfashion, #convert, #jilbab, #khimar and many more, and thus attract more and more followers on a global scale.

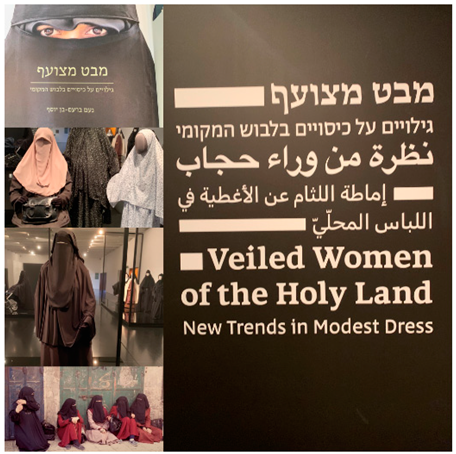

Another source of information for the discussion of modesty was an exhibition taking place exactly at the writing of this manuscript: “Veiled women of the Holy Land, New Trends in Modest Dress”, curated by No’am Bar’am Ben-Yossef (see Appendix B).

In Israel, in the past two decades, it has become increasingly common to see Jewish and Muslim women alike covering their entire body with several layers of shawls, wraps, and veils in adherence to strict laws of religion and modesty. From a distance, it is difficult to tell them apart, and some also recall Greek and Russian Orthodox nuns. To gain insight into the rationales behind this trend, women from the different religious groups were interviewed, yet the topic remains fraught with contradictions: do the multiple layers covering the woman’s body protect her or do they reflect centuries of oppression? Is this yearning for modesty a reaction to the lay women’s permissive dress code? What feelings does it arouse in us? And what forces lie behind it? The exhibition presents the attire of each group, photographs and texts, and a video work by art director and consultant Ari Teperberg offering a glimpse in the women’s private world, a Christian woman who became a Nun, a Jewish woman who turned to Orthodoxy and a Muslim woman who started to wear Niqab, in spite of objections from her family and friends. Together, through video art, they invite viewers to grapple with these questions—and answer them in their own personal way, while showing the viewer their clothes and headcovers, sometimes so different, yet sometimes so similar in the three Abrahamic religions. (See more about a recent debate in Israel about the right of a (religious Jewish) woman to cover her hair in the public sphere in Appendix E).

5. Conclusions—Classy and Modest, Hip in Hijab