1. Introduction

In the context of our work, we want to emphasize how different “masks” and faces of religion play multiple (social) functions—from providing a reference framework for the interpretation of the realities of life and the world around us through setting personal goals to forming social and political relationships between groups—and as such. Under certain circumstances, they can serve as fertile ground for distance and closeness toward the non-members of their own (ethnic, religious, cultural) groups (

Hunsberger and Jackson 2005). Accordingly, we can say that different dimensions of religiosity may have different impacts on the development of distance and prejudice toward

others and toward minorities.

This role of religion as a “mask” and “cover”, as in the case of the Former Yugoslavia, can still be seen in the Western world today, in the way that religion comes to the surface with ancient identities, opponent of the enemies. In this sense, religious self-identification and religious practice, within a ceremony or a cult, become one of the most effective factors of socio-cultural differences within religious distance (

Marinović Jerolimov 2008).

It is also important to emphasize that, along with (non)religiosity, prejudice toward the Other can be influenced by traumatic experiences from childhood, insufficient intercultural education, upbringing in single families, life attitudes, and (non)existence of contacts with minority groups of a particular society (

Allport and Kramer 1946). Thus, there are a number of factors that should serve as control variables in the research.

Religious self-identification belongs to the dimension of religious belief, which implies a set of individuals’ attitudes toward a higher being or power, understood as transcendent or mysterious. It can also denote the complexity of dogmas or religious truths, accepted as a necessity of clinging to a transcendental principle that can be perceived as a personal being, as an inherent force or power, as the order and unity of everything created (

Acquaviva and Pace 1996).

The dimension of religious practice, although underwhelmed by numerous and fiery discussions, has been thought out by Allport in his differentiation between internal and external religion. He distinguishes a practical believer who uses the acts of faith to express his/her loyalty to his/her own social group from a believer who finds the opportunity to live his/her own faith in practice (

Acquaviva and Pace 1996). Thus, self-identification (cross, rosary) and religious rituals (church attendance, pilgrimages) may be the integrating resources and unifiers of the national collective.

We have accessed the empirical data collection within a multiple theoretical framework. The first part analyzes social distance in the socio-historical cultural context and intertwined realationship between religion and nation in Croatia and its product—political instrumentalization of religion i.e., political Catholicism, while the second deals with theory of social distance and religious factors of social distance.

1.1. Social Distance and Context of Social Integration

The concept of social distance has been designed by Emory Bogardus and has been around since the 1920s as a simple yet effective research tool for studying intergroup/interpersonal relationships (

Parrillo and Donoghue 2013) and the degrees of understanding/acceptance and intimacy that characterize (pre)social relationships (

Bogardus 1925). Although social circumstances have changed over time, and thus theoretical and methodological assumptions of sociological research have also changed, “Bogardus scale of social distance remains a relevant research tool, as evidenced by a number of recent papers on this topic, published both in the US and in other countries” (

Parrillo and Donoghue 2013, p. 598).

In general, when social distance is examined, the relationships and attitudes of members of one (ethnic, religious, racial, etc.) social group, perceived by the respondents as theirs, are examined and compared to the members of another social group perceived as the Other. By offering explanations of distance toward other/outer groups,

Bogardus (

1925) points out that they are mostly associated with fear. Namely, the most common causes of distance are traditional beliefs and acceptance of public opinion, unpleasant personal experiences from childhood and unpleasant experiences into adulthood. In addition, Bogardus points out that individuals often incorrectly generalize the activities of several members of the group that they have personally encountered to the whole group.

Distance values are affected by the cultural aspects and differences between “foreigners” and the local population. In the circumstances in which “natives” feel more vulnerable or think their (social, economic, health) status is questioned, the value of social distance increases (

Bogardus 1926). It is therefore expected that, in the period of refugee/migrant crises and the growing number of asylum seekers in the territory of the Republic of Croatia, a social distance from Muslims will arise. Namely,

Parrillo and Donoghue (

2013) state that external influences or circumstances under which research is conducted strongly influence the degree of distance that members of a particular group/society express in a certain period. Thus, for example, after the Second World War, the US citizens expressed low acceptance values for Germans and Japanese while, on the other hand, during the Cold War, their place was occupied by the Russians. Likewise, after September 11, 2001, the greatest distance was expressed toward the Arab population and to the Muslims in general (

Parrillo and Donoghue 2013).

When defining the key determinants of distance values,

Parrillo and Donoghue (

2013) point out the similarity of groups/individuals or at least their perception. Any researcher who examines attitudes toward other groups and its members should keep in mind Aristotle’s observation that people love and accept “similar to themselves—people of their race, age ⋯ those with whom they are on the same level” (

Parrillo and Donoghue 2013). However, the authors emphasize that the perception of similarity is often a more significant determinant at distance representation than real similarity. Allport’s claims are similar to the above-mentioned. He emphasizes that contact between groups can reduce prejudices, but only if groups (1) have the same status, (2) share common goals, (3) cooperate, and, finally, if they (4) receive support and benefits from authorities (

Parrillo and Donoghue 2013).

Although it should be kept in mind that there is often a difference between attitudes expressed in research and concrete actions in practice (

Parrillo and Donoghue 2013), the concept of social distance is useful because it enables the explanation/prediction of human behavior by examining attitudes that “drive human to activity and action and direct an individual to an emotional, value and active relationship with people and phenomena” (

Mrnjaus 2013, p. 312). One of the key features is group categorization or possession of a group identity through which an individual develops a relationship with a related (religious, sexual, racial, age) group (

Mrnjaus 2013). We will try to figure out what role, in the whole story of group identity and (non)acceptance of others, is played by religion and religiosity.

When analyzing this relationship, we will rely on the paper by

Dugandžija (

1986), who points out that the examination of relations between religion and nations is justified in many ways; namely, although religious life is not only based on nationality, the tendency of linking these two phenomena has always been stronger than the tendency to divide the two terms. Linking, the author emphasizes, goes so far as to make expressions like “the Catholic nation”, “the Orthodox nation”, the “Muslim nation”, etc. The possibility and simplicity of replacing the nationality and its products with religion, as well as religion with the nation, according to Dugandzija, is the result of the ease of adopting the same functions.

The mentioned national and religious homogenization of the Croatian population during the war of 1990s reflected on the generation of a value system still present among a number of Croatian citizens, which implies the identification and firm intertwining of both the national and the religious as well as the Croatian and the Catholic. The aforementioned processes have gradually “prepared” the space for the emergence of

political religion—a secular mechanism that arbitrarily chooses within a religious field and chooses only the aspects of religion which can be used in secular (ideological, political, economic) conflicts with others (

Berdica 2014).

Šarčević (

2011, p. 448) emphasizes that contemporary political Catholicism has its socio-psychological reason in the mechanism of biological and social defense: once as a struggle for social power and domination, and secondly as a cohesive force for biological survival before the threat of disappearance. With such a perception of religion goes the claim that religion acts as a policy of identity. This term Enzo Pace uses in his book

Why Religions Enter War?

Pace lists five basic principles of identity politics (

Pace 2009):

Political identities are social, but also political movements.

Identity becomes something that is unquestionable, sacred and unchangeable.

Identity serves to strengthen social activity.

Religion, using rituals and symbols, indirectly generates the space within which (national) identities are perceived to be endangered by the enemies.

That in the efforts to preserve the endangered identity conflicts with the enemy represent the battle of the Good against the Force.

It is clear, and even

Pace (

2009) himself claims that, in Croatia, it has happened just as described above. Religion for Croats has become a means of struggle, and turned into a means of construction, or more precisely preserving and reconstructing the national identity of the people themselves.

At the same time, behind the curtains of the public, there are new sanctities and sacred places for those who have carried out the double masquerade of every ideology: trade and the media become a mask and a substitute for religion and politics. Hence, Croatian political Catholicism is justified by a cohesive force for biological survival as the most appropriate response to the confrontation with Islam and Orthodoxy on the mixed geographic area (

Šarčević 2011, p. 449).

Fundamentalism—political Catholicism opposes secularization in the form of Catholic fundamentalism. It does not allow theological pluralism (

Mardešić 2007, p. 30) or a dialogue with non-believers outside the Church and believers within the Church.

Dualism—political Catholicism necessarily includes religious dualism which ethically divides the world on good and evil (

Mardešić 2005, pp. 46–47). Evil moves beyond itself, beyond us Christians/Catholics, and places it far from us, into the Other.

Resentment—political Catholicism marks the fall in the undemocratic past (

Mardešić 2007, p. 851) and the abomination. Young people tend to live in the time of their predecessors—in some ancient centuries and times, ’devoted’ to unforgettable, forgiveness and reconciliation.

Integrism—in the unstable times, times of the fall of the regime and transition, pluralism, fragmentation of ideas and movements, integrism is offered as a hard, collective response and the cohesive power of the endangered (

Mardešić 2007, pp. 172–73). Croatian-Catholic integrism insists less on Christian teaching, theology, and much more on the ritual and symbols that serve as the integrating tools and the unions of the national collective.

Stereotypes and demonizing metaphors—political Catholicism as well as any ideology does not endorse scientific argumentation but uses phrases, slogans and stereotypes. For the purpose of Catholic integrism, sacred texts are used and they are overly synchronously interpreted. History is full of mythological images of ourselves as victims and full of demonizing metaphors and images of others.

Anti-Communism—one of the main components of the current Croatian political Catholicism is anti-communism manipulated by various traders and perpetrators.

Pre-council Catholicism—political Catholics do not accept the Council or make it very selective. The Church (in Croatia) is a prehistoric entity today, and political Catholicism overcomes the conceptual Christianity, and the tradition overcomes modernity.

In this sense, our important subject of the research refers to the religiosity that insists less on Christian teaching, theology, and much more on the rituals and symbols which had been internalized through specific religious self-identification and Church attendance.

Determining the logic of acting politics toward religion in a way that: “arbitrarily chooses within a religious field only what uses in secular clashes—ideological, political and economic—against others, we call political religion or religious politics” (

Mardešić 2002, p. 49). Therefore, in the interpretation of the obtained results on distances and prejudices against Muslims, as well as acts of terrorists and extremists, the phenomenon of political religion should certainly be taken into consideration.

Since social distance is closely related to the broader socio-political situation, it is not necessary to over-emphasize the influence of the current geopolitical situation in the Middle East and the omnipresence of “Islamic terrorism” in daily media life of the West as well as of the Republic of Croatia. These phenomena certainly can (and probably they have already done it) create the environment and the overall socio-political context for developing negative attitudes toward Muslims and Islam in the West as well as its satellite countries (which Croatia certainly is).

1.2. Self—Identification and Religious—Practice in the Context of Social Integration

The social context of religious life in Croatia is manifested mostly through two periods; the period from the Second Vatican Council to 1990, marked by the dominant socialist-Marxist paradigm, which has pushed religion into the domain of privacy; and the second period from 1990 until today, marked by the birth of the national state, the Homeland War and the transition of Croatian society from the socialist to parliamentary and democratic one (

Kovačević et al. 2016).

With the end of the war and the transformation of the system, Croatia did not only come to political or economic changes, but also to a large number of religious changes, within different dimensions and aspects of religion as such. The role of religion and the Church in Croatia has changed completely. As in most post-communist states, their presence in public life is no longer “invisible” as in communism.

Marinović Jerolimov (

2009) points out that the main framework of change is the opening up of the leading social structures, and the very society, toward the Church and religion, followed by institutional solutions to the relationship between the state and the Church, as well as national and religious homogenization (in the 1990s, 30 percent more citizens declared being religious).

Therefore, we can conclude that Croatia shows a dominant process of strengthening traditional church religion and religiosity (especially Catholics) that contain a certain national and political identification (

Marinović Jerolimov 2009). One of the fundamental social issues that emerges after the war and the transition of 1990s is to what extent the ethnic and national prejudices within the prevailing Croatian nation are spread, i.e., to what extent Croatian citizens are aware of the fact that even after the Homeland War Croatian society is multiethnic and there are members of other religious groups and communities (

Malenica 2007).

Multiethnicity of the Croatian society are certainly enriched by Muslims who have lived for centuries in the areas of today’s Republic of Croatia.

Markešić and Rihtar (

2016) point out that for historical reasons (the Ottoman occupation), Muslims, as well as their religion, have for a long time been perceived as something strange for this region, for the people, and their religion. Muslims, the authors continue, were not perceived or acknowledged as a separate equivalent religious or national community. However, thanks to the change of historical circumstances (military and political defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the fall of Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the aspiration of European peoples for free expression of religion and national affiliation), Islam was recognized in 1916 as a ‘state’ religion, equivalent to other religions in countries of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, and thus of Croatia (

Markešić and Rihtar 2016).

An insight into the situation 100 years later offers us an analysis of the results of the Pilar Barometer of Croatian society (

Markešić and Rihtar 2016). The conducted research has shown that about eight percent of the Croatian population is particularly interested in Islam (or inclined to learn more actively about it), with the majority of the public (58 percent) receiving information about Islam through mass media. Family, in addition to religious institutions, is in this regard the least important factor. Most of the respondents could not opt for the question of immigration of Muslims from distant countries while more than half of the respondents perceive Islam as peaceful religion and do not perceive Muslims as a threat. However, Islam is not considered a part of Croatian culture and tradition. The threat is somewhat more felt by a right-oriented part of the public, who, alongside the more religious respondents, less than other respondents see Islam as an integral part of Croatian culture and tradition (

Markešić and Rihtar 2016).

Furthermore, aforementioned research was conducted during spring 2015, or around half a year before the arrival of the refugee wave in Croatia. Since our research was carried out during the migration and refugee crisis that have been shaking Europe (and thus also Croatia) and since the research was done during the increasingly frequent terrorist attacks in European cities, we were interested in attitudes and opinions about Muslims under changed circumstances, i.e., whether and to what extent there is an impact of religion self-identification and church attendance on social distance shown toward them.

We can assume that in our case the religious factors will be important in forming students’ attitudes toward Muslims. This is also supported by the results of social research studies conducted on Croatian territory—a greater distance is expressed by more religious respondents, convinced believers (who accept everything that their religion teaches), those who regularly attend church (

Marinović Jerolimov 2008) and respondents of Croatian nationality and Catholic religious beliefs (

Blažević Simić 2011).

The reason for the continuous confirmation of this pattern of respondents in social distance research should be sought in aforementioned social and political context in which the Republic of Croatia has been in the past 25–30 years. The Homeland War and the accompanying homogenization of Croatian population, both political and religious, have created a kind of national and religious cultural pattern that is still present in Croatian society. In the words of Jukic, we can say that this is about the political ideology of religion, which in history “is so much proven and confirmed that only the blind man cannot see it” (

Jukić 1997a).

One of the foundations of current civilization division (between Christians and Muslims) can, among other things, be sought in religion or its particular features. Namely, religion has a significant role in the formation of prejudices toward minorities (

Jeong 2017) and, as such, it is along with nationality a relevant factor in researching discrimination of members of other/outer groups (

Hunsberger and Jackson 2005).

Many authors tried to find an explanation for this, at first glance, unusual and illogical interplay. Frenkel-Brunswik and Sanford point out that individuals who exhibit a high level of prejudice have been educated in a way that they are subjected to external, institutional authorities, which later implies a certain type of hostile attitude toward groups that do not obey the same institutional authority (

Allport and Kramer 1946). However, it should be borne in mind that the mere presence of religious teaching in a family or church, i.e., the exposure of an individual to religious education and teaching does not lead itself to increased tolerance and openness, but only to certain forms and perceptions of the religious (those emphasizing the openness and acceptance of the Other) can do that (

Allport and Kramer 1946).

- (1)

Personal religious orientations represent sources of meaning.

- (2)

Motivational aspects of personal religious orientation.

- (3)

Religion represents a framework for accepting individual and social values.

- (4)

Religion can act as a means of group identification and group conflict.

Likewise, prejudices may also be conditioned by other (non-religious) factors. For example, if a cognitive aspect is observed, individuals can use prejudices as mental shortcuts or explanations that help them process new information and form attitudes (

Jeong 2017).

The past Western papers, as we have already seen, show contradictory results; therefore, it is possible to conclude that religiosity reduces prejudice and increases tolerance and acceptance of other communities (

Hunsberger and Jackson 2005), but also it is more likely that more religious individuals will be less tolerant or have more prejudice toward minority groups (

Allport and Kramer 1946;

Batson et al. 1993). The reasons for such contradictory results can also be found in the methodology of researches which often use only one or two dimensions of religiosity as an independent variable, which can lead to incomplete and inadequate generalizations. Nevertheless, regardless of the diversity of results, the fact is that group religious identification can provide individuals with a framework of meaning within which they will form their attitudes and opinions (

Jeong 2017).

As the title suggests, our paper addresses the influence of two dimensions of religiosity (religious self-identification and religious practice) on social distance toward Muslims. In this sense, we have tried to investigate how much religious self-identification is a factor of social integration (

Jukić 1999), or an attempt to conform to one’s own social group; and how much in life practice, finds the opportunity to live its own faith.

2. Methods

Religious self-identification of respondents is measured by the continuum of six offered categories—I am a convinced believer and accept all that my religion teaches; I am religious, though I do not accept all that my religion teaches; I think a lot about it, but I am not sure whether I believe or not; I am indifferent toward religion; I am not religious, although I have nothing against religion; I am not religious and I am opponent to religion—each respondent classifying herself/himself in one of them.

The scale of religious self-identification has been used since the 1960s by the Institute for Social Research in Zagreb. In the first research of religiosity in the Zagreb region in 1968, B. Bosnjak and S. Bahtijarevic took the scale over from the Center for the Study of Religion at the “High School for Sociology, Political Science and Journalism” in Ljubljana. The reasons for the use were comparative; namely, such a scale made it possible to distinguish also the levels within the category of religious and category of non-religious subjects as well as those in-between these two types of relationship to religion (uncertain and indifferent ones) (

Bezinović et al. 2005).

The second studied independent variable of religious practice can be taken as an indicator of the degree of belonging to a particular religious group, but it should be observed separately because there are typologies of practical believers with a low sense of belonging to the community (in many churches of modern society, both Catholic and Lutheran) (

Acquaviva and Pace 1996). It was included in this research in order to gain insight into the frequency of attending church or religious ceremonies.

Based on previous research (

Blažević Simić 2011;

Malenica 2007;

Marinović Jerolimov 2008), we assumed that religious distance is widespread in terms of religious self-identification and religious practice of respondents, in which (1) convicted believers and (2) those who regularly attend religious practices will show greater distance to Muslims and Islam.

2.1. Questionnaire, Procedures and Participants

For our research measuring instrument, we chose a survey questionnaire, which is often used in sociology as a tool for collecting and analyzing the views and opinions of a large number of respondents.

The questionnaire consisted of 29 questions, mostly closed type, and besides the standard questions and possible answers, the Bogardus social distance scale and Likert scale were used for individual variables (with the range of answers 1—I completely disagree to 5—I completely agree). The concept of social distance refers to a continuum that moves from intimate relationships through indifferent to hostile ones while the scale consists of seven classifications and the respondents indicate one that they consider to be appropriate to their position.

As far as the distance toward social groups is concerned, the continuum begins with the classification of readiness to have a close relationship through marriage, which represents the most intimate degree of closeness, and ends with the classification of exclusion from the state that represents the highest degree of distance toward that group. Generally, in surveys using this scale, it is assumed that the scale is evenly graded so that respondents, marking one of the seven offered responses, accept all other responses that are less intimate than the indicated response in terms of the degree of closeness.

However, we decided to use a modified Bogardus scale consisting of nine assertions. In fact, it was a synthesis of Bogardus and Likert scales with the offered answers from 1 (I completely disagree) to 5 (I completely agree). Therefore, each classification is separate and each of them shows the degree of agreement. We have based our criticisms on three cognitions of the Bogardus scale: (1) assumption of equal intervals between the points of the scale, (2) assumption that each point is necessarily above the other preceding it, and (3) the fact that we can only test the reliability with the awkward test–re-test technique. Our revisions were an attempt to increase the reliability and sensitivity of the scale itself, though, by accepting some of the items listed, respondents do not necessarily have to accept all other items included in the same scale. Although this modification so far has not been applied in sociological methodology (and, hence, it is not accepted as valid and reliable), in this way, it is possible to measure values for each social distance indicator separately, avoiding discussion of the equal intervals between the scale points. In addition, it gave the respondents possibility to express an attitude for each statement separately without being forced to accept or reject it absolutely.

For the purpose of this paper, a probabilistic, stratified sample of 286 respondents (n = 286) was identified, all of whom are students of the University of Split, although it would be interesting to see data for the entire population of Split or Croatia in the near future. In our case, the control stratums in the sample were represented by a certain study orientation of our students so that the sample was divided into four categories: students of social sciences, humanities, natural sciences and technical sciences. This suited the individual goals and hypotheses of our paper.

As far as sample structure is concerned, 39 percent of men and 60 percent of women participated in the study, while 1 percent of respondents did not answer this question. The sample was stratified by the type of study orientation, so that following students participated in the study: students of humanities (24.5 percent), social sciences (27 percent), natural sciences (25 percent) and technical sciences (23.5 percent).

Most of them were second-year students (40 percent) and third-year students (39.5 percent). The highest percentage of the respondents said their mothers (guardians) finished a secondary vocational school (54.5 percent) or had a higher education or university degree (22 percent), while 54 percent of respondents indicated that their fathers finished a secondary vocational school. Additionally, 14.5 percent of respondents said their fathers had a higher and 20.5 percent high education degree. In the categories of the poorest household by monthly income (less than HRK 2000), there are 4.5 percent of respondents in total, while the other categories are more evenly represented. Nevertheless, as expected, the highest percentage (35.5 percent) of respondents are classified into the middle category (HRK 6000.01–10,000).

Furthermore, the sample consists of mostly Catholics (81.5 percent), while no respondent declared herself/himself an Orthodox, Muslim or Jewish, the three most represented religious groups in Croatia. Still, 3 percent of respondents belonged to another religion but no one indicated which one. On the scale of religious self-identification, 38 percent of respondents are identified as convinced believers, while 35.5 percent of them are religious people who do not accept all that their religion teaches. Finally, 37 percent of respondents regularly (daily or weekly) go to church.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Regarding the relation to Muslims, the total score on social distance was measured by the responses to questions about hypothetical real-life situations. The highest total score on nine items on a five point Likert type scale could be 45 and the lowest could be 9. Data analysis was performed using RStudio (ver. 1.1.463, RStudio, Boston, MA, USA) and R language (

R Core Team 2013).

Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were expressed as the means and standard deviations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the differences in total social distance mean score among three different levels of religious church attendance and religious self-identification variables. The religious church attendance variable divided respondents into three groups: those of them who attend church daily or once a week; monthly or rarely; and those who never attend church. Previously, a religious self-identification variable divided respondents into three groups: believers, belong but do not believe, and others.

3. Results

The results indicate that as many as 17.5 percent of respondents would not accept Muslims as Croatian citizens. The same percentage applies to having Muslim neighbors, with a slightly higher percentage (18 percent) of the disapproval of a Muslim boss at respondents’ work. The highest rates of disagreement were obtained for questions of accepting Muslims in their families through marrying them or letting their children marry them (46.5 percent), leading the country (38 percent), having Muslims as relatives through marriage of family members (31 percent) and having Muslim teachers of their children (47 percent).

On the other hand, the smallest distance was obtained in terms of accepting Muslims for socializing (15 percent) and as colleagues at work (11 percent). Thus, almost half of the respondents do not accept marriage with another person if the person is a Muslim, or only a quarter of the respondents (26.5 percent) is ready for it, and the same percentage of respondents cannot assess whether they would accept the marriage or not. Acceptance of Muslim relatives is fairly more pronounced, but, still, almost one third of respondents (31 percent) disagree with this option. On the other hand, almost one third of the respondents would not allow (17.5 percent) or did not know if they would allow (13.5 percent) Muslims to be citizens of Croatia. Still, here we would like to emphasize that these results about accepting marriage with Muslims are not necessarily the result of anti-Muslim sentiments. It is probably that highly religious people of all religions prefer family marriages within their own religious cohort. Thus, that reality is possibly a factor in total social distance scores.

In the second step, we made an analysis of social distance toward Muslims according to two important variables: church attendance and religious self-identification. There were differences in responses and acceptance of Muslims in real-life situations according to questions on social distance scale.

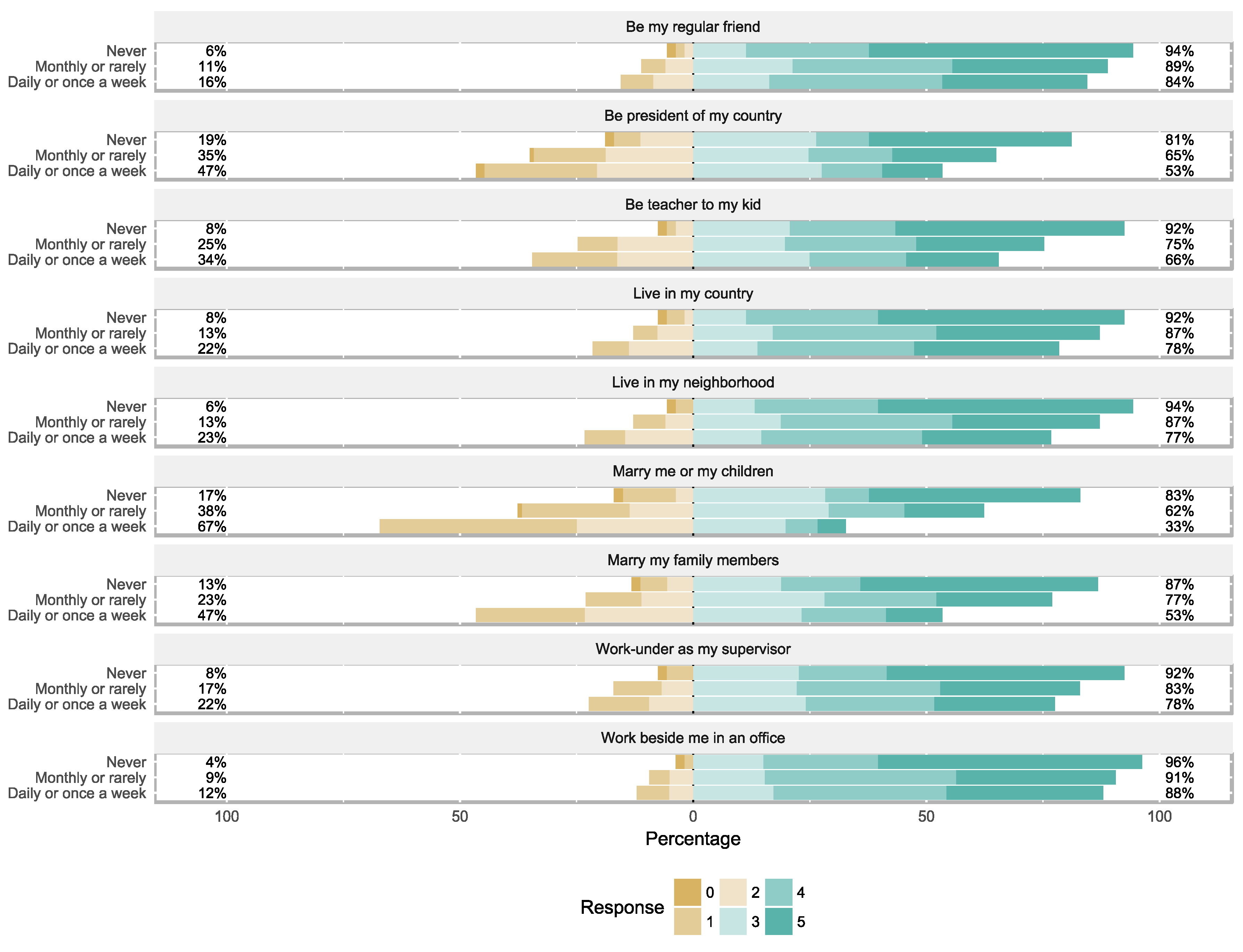

Figure 1 shows that more than 80 percent of students who never attend church accept Muslims in each situation in real-life. For example, 92 percent of them accept that Muslims could teach their children while 83 percent accept that Muslims could be members of their families. On the other hand, only 33 percent of respondents who attend church daily or once a week accept a Muslim as a family member and 66 percent of them accept that Muslims could teach their children.

The second important variable in the research was religious self-identification.

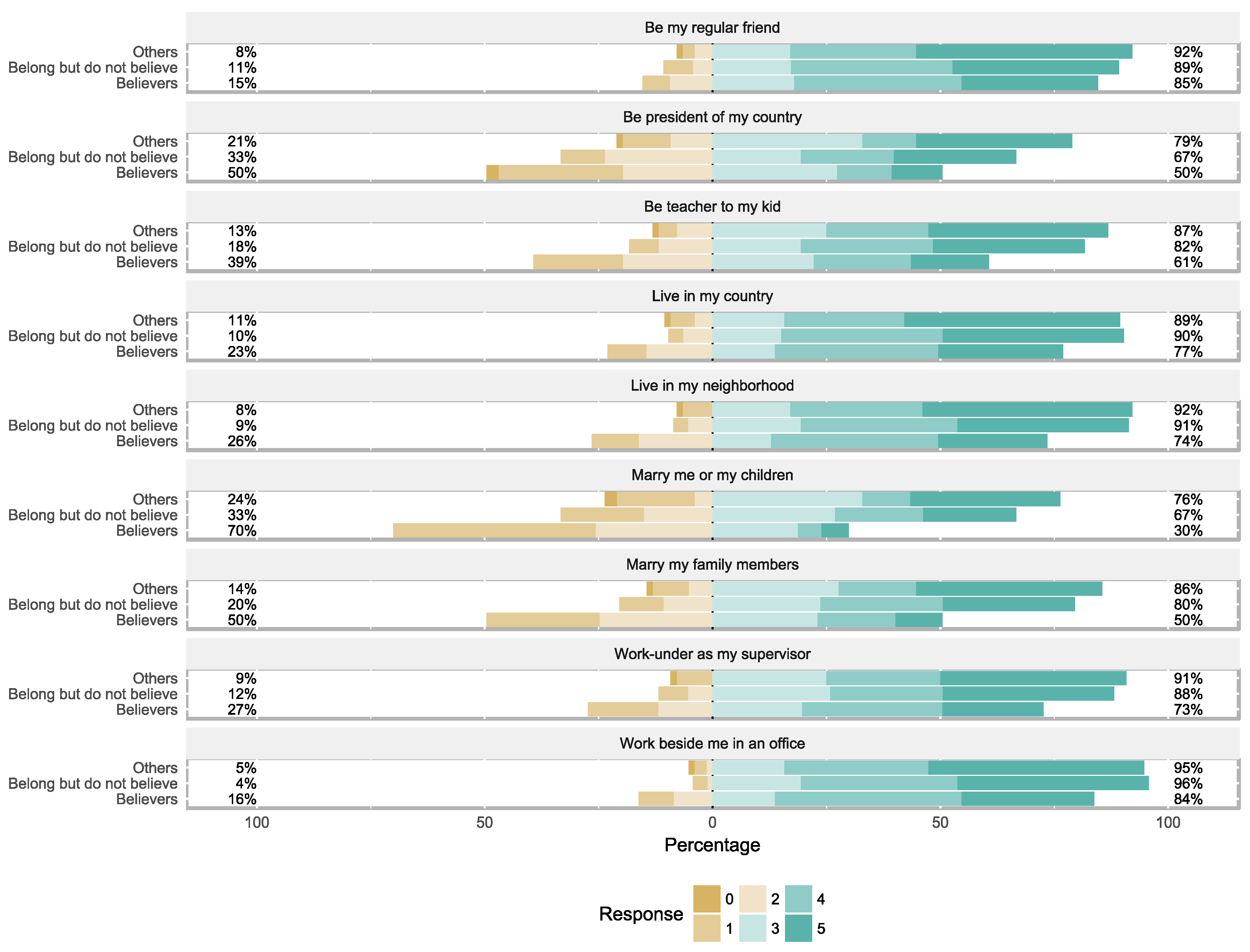

Figure 2 shows that at least 76 percent of respondents who are not believers accept the Muslims in any real-life situation. For example, 92 percent of them accept that Muslims could be their friends while 87 percent accept that Muslims could teach their children and 76 percent that Muslims could be their life partner or married to their children.

The results are quite different in respondents who are believers or respondents who belong but do not believe. Believers accept Muslims in 30 percent of cases as life partners or in marriage with their children while 50% of them would accept Muslims to marry with their family members and 61% accept that Muslims could teach their children.

These results were the reason for significant difference in total score on social distance, which was expressed as a sum of responses on each situation. There were statistically significant differences between religious self-identification groups (F = 14.14,

p < 0.001).

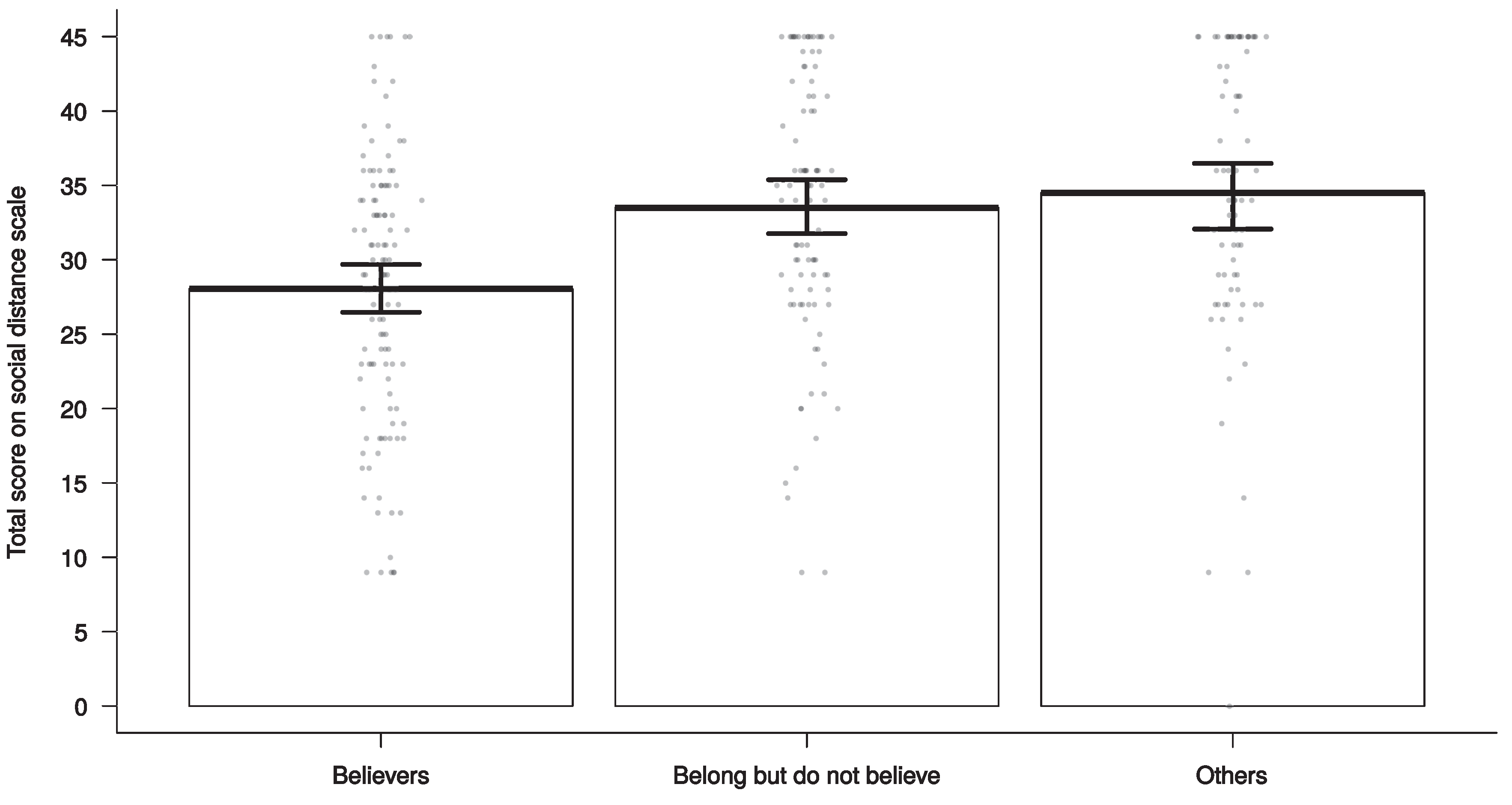

Figure 3 shows that believers showed statistically significant difference (

p < 0.01) in social distance mean score (28.1) in comparison to respondents who belong but do not believe (33.5) and others (34.5).

There were also significant impacts of religious service attendance on social distances toward Muslims.

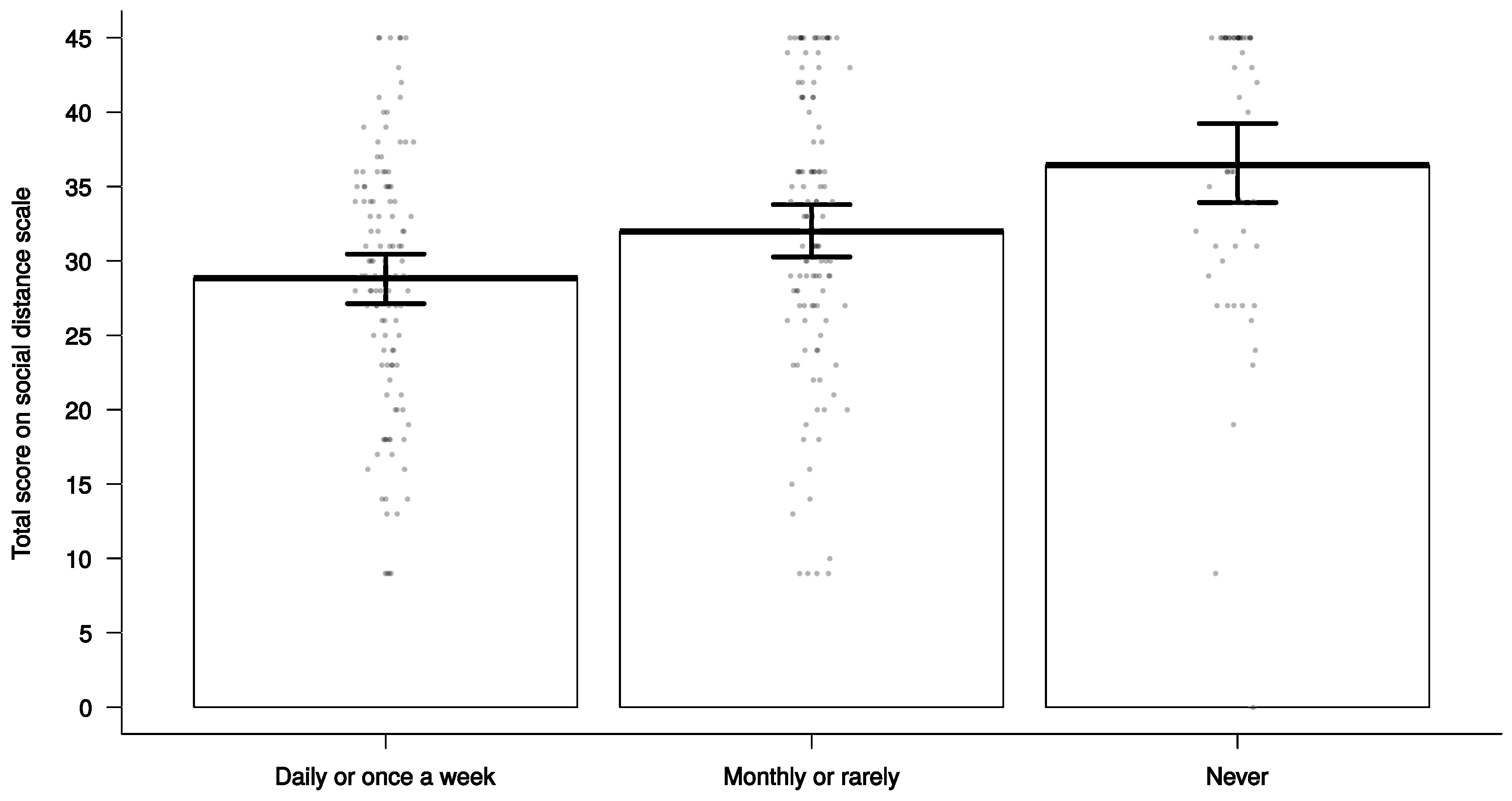

Figure 4 shows that respondents who go to church daily or once a week have a lower level of social distance mean score (28.8) compared to respondents who attend church monthly or rarely (32) and those who never attend church (36.4).

Similar to the ANOVA results on the self-identification variable, there was a statistically significant difference among these scores (F = 12.14, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis shows that respondents who attend church daily or once a week statistically significantly differ from those who attend church monthly or rarely and those who never attend church.

4. Discussion

At the beginning of the discussion, it is necessary to point out that the obtained results on the one side can be understood on the descriptive level and on the other side within the differences in social distance values in regard to mentioned predictors (religious self-identification and religious practice). Therefore, we consider that the analysis of our results needs to be divided into two levels: the first focuses on (1) understanding of the descriptive data of the distance toward Muslims, while the other is directed on (2) social distance differences in regard to the two observed dimensions of religiosity (religious self-identification and religious practice).

The first one we consider as more under the influence of global context that implies the influence of the socio-historical situation of Europe and Western civilization, while the other has more been influenced by local context and the associated social phenomena and processes arose from complex interactions and interrelationships in the latter 30 years in Croatia and former Yugoslavia. Thus, the first level relates to the relevance of the data obtained and analyzes in the European context while the second relates to the national context, which is related to the social and political situation in the Republic of Croatia, and the implications that our results have within it.

Of course, we must not lose sight of the fact that this national context is a part of a wider European context, so it is impossible to strictly specify and isolate it from the continental and even the global context. On the other hand, the socio-political situation in the Republic of Croatia is of particular importance for European context not only because it (since 2013) is one of the members of the European Union, but also because Croatia, given its geographic position and border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, has an important strategic role. The importance of this role is not only manifested in political or economic aspects, but also in the socio-cultural one. For this reason, we would like to offer this research as a small, but significant, scientific contribution to the current social problem.

Comparing results with already existing research (

Allport and Kramer 1946;

Batson et al. 1993;

Beatty and Walter 1984;

Blažević Simić 2011;

Jeong 2017;

Malenica 2007), we can see how the pattern of respondents showing a greater distance has been confirmed. The reason for the continued validation of this pattern in social distance research can be explained by analyzing certain features of religion, but taking into account the social and political context in which the Republic of Croatia has been in the past 25–30 years. Thus, after reading the results, there are two questions which are being set up:

(1) Why are the values of the distance (at the descriptive level) such as they are?

Firstly, we have to emphasize that it is not possible to scientifically determine the limits and percentages of significance of the descriptive datas. For example, it can not be asserted with certainty whether 30% of students, who do not accept Muslims as citizens of the Republic of Croatia (or they do not know if they would accept them), is a large or small percentage—scientifically significant or not, worrying or encouraging. However, we can conclude that this is something that should be considered, especially because it is about the student population. Students are certainly a valuable source of information, not only for the current situation but also for predicting the future. We are of the opinion that the stated values of the distance are primarily due to the current global geopolitical situation and related migrations that certainly affect student attitudes. Of course, here it is not just about the last few years and waves of migration, but the long lasting process of immigrating the Arab population to the West. Theory of cultural differentialism (

Ritzer 2006) certainly helps in understanding the situation because it emphasizes the irreconcilable differences between the two cultures. It is also a long-standing process of stereotyping Islam, Muslims and Arab culture through production and reception of Western media content. Of course, this has a significant impact on the meaning construction and generating attitudes of the Croatian population, which is a political, economic and cultural part of Western civilization. Therefore, it is hard to expect that the anti-Muslim trend, which has long been present in the West, bypasses Croatian citizens, especially students which are, to a large extent, part of the global digital platform and social networks, and thus part of global social trends.

On the other side, it is understandable that the periods of crisis (and Croatia was again/is still in such a period) lead to uncertainty and an unforeseeable future, creating fear and discomfort among the majority of the population, especially among young people. Namely, if we objectively look at the circumstances of Croatian reality over the last 30 years, we see that modern generations of young people mature in significantly more risky conditions, marked with processes and consequences of globalization, an increasing demand for professional mobility and flexibility and the development of information and communication technology (

Ilišin et al. 2013).

Furthermore,

Ilišin et al. (

2013) point out that (post)modernization processes transform and break down the well-known forms of social reproduction, which force young people into a more uncertain and more difficult search for identity and individual strategies of social integration. If we add the transitional context, the risks that young people face are further expanded, in comparison to young people from developed countries and compared with younger generations of youth in the socialist society.

Thus, growing up in this unique socio-historical period is characterized by a double transition: first, young people pass through the universal transitional period from youth to adulthood and, secondly, this process takes place in a society that is in the process of social transformation itself. Therefore, it should be emphasized that their socialization takes place in conditions where the institutions, processes and social norms used to direct the transition to adulthood have disappeared, or they themselves are thoroughly transformed (

Ilišin and Radin 2007). Since Croatian society belongs to the category of (post)transitional societies which are affected by the processes of globalization, the Croatian population of young people, under the direct influence of these processes, feels insecurity and the lack of a positive perspective, which is why they need protection so as not to acquire the collective sense of helplessness and lethargy (

Stefančić 2010). However, since this protection, as well as the strategy, is lacking in society, the young feel insecure, in certain situations even scared of the future. This fear, which is a reflection of existential material endangerment, is manifested in the young being not receptive and showing the distance toward strangers and the Other. It is also understandable that the aforementioned socio-historical moment is such that the distance toward the Other in general is unlikely to equal the distance toward Muslims, but it was one of the reasons for carrying out this research and dealing with this topic—to achieve not only scientific but also make a social contribution by pulling out the data which are necessary to make further strategies and actions on one of the most current European themes today.

(2) Why do respondents who declare themselves as convicted believers (accept everything that Christianity teaches) and those who regularly attend religious rituals show greater distance toward Muslims?

This is actually the key question and the most interesting issue of our work. It is a question that can not be answered only by considering a global context and the already existing explanations of the complex interrelations of Christians and Muslims in Europe. It is necessary to dive deeper into the local context and to take into account the social developments within the Republic of Croatia for the last 30 years. To understand this context, we need a theory of political religion or political Catholicism that explains the interweaving of religious and political/national. We are of the opinion that Croatian political Catholicism spoken by Mardešić (

Jukić 1997a;

Mardešić 2002,

2007) is one of the most appropriate theoretical frameworks for understanding our results. Those results raise the question of whether institutional religiosity generates such a value, perceptual and ideological pattern that, inter alia, manifests by expressing prejudice, the rejection of the Other and the unwillingness to accept a different one. Convicted believers and regular attendants significantly statistically reject Muslims more than those who do not declare themselves as such (religious who do not accept all that their faith teaches and nonbelievers) as well as those who do not attend regularly religious ceremonies. This is actually the outcome of manipulation and instrumentalization of religious content and learning for secular (political, ideological, economic) purposes. It is about achieving personal and group benefits of certain interest groups and social structures that have abused their own social positions and roles in a complex socio-historical situation—the fall and the change of system, transition, transformation and, worst of all, the bloody war and its associated atmosphere of fear and closure. This is exactly what Mardesic (

Jukić 1997a;

Mardešić 2002,

2007) speaks of when he lists key features of Croatian political Catholicism—the emergence of fundamentalism, self-closure, and generating distrust, the emergence of integrism as a collective response to the existential vulnerability of one’s own social group, the reproduction of mythology of one’s own past and nation and the stereotyping of the Other, the manifestation of the anti-communist attitudes that have become one of the greatest links of the new nationalist political elite and high religious officials. Furthermore, it is interesting to see Mardešić’s view from a religious or theological Christian perspective, pointing out that one of the features of political Catholicism is Christian inadequacy and inadequate understanding of Jesus’ doctrine. Causes for that author finds in pre-council Christianity that does not accept the legacy of the Second Vatican Council and its corresponding proclamation about accepting and opening the world, science, diversity and modernity in general.

Thus, the Homeland War and the accompanying homogenization of Croatian population, both politically and religiously, have created a kind of national-religious cultural pattern that is still present in Croatian society. As

Marinović Jerolimov (

2009) points out, Croatia shows the dominant process of strengthening traditional church religion and religiosity (especially Catholicism) that contains a certain national-political identification. Croatian constitutional changes during the 1990s, as in most post-communist states, increase the presence of religion in public life. The main framework of changes in this period is the opening up of the leading social structures, and the society itself, toward the Church and religion, followed by institutional solutions of the relationship between the state and the Church, as well as national and religious homogenization (in the 1990s, 30 percent more citizens declared themselves as being religious) (

Marinović Jerolimov 2009).

In Croatian Catholicism, the religiosity has been ideologically, therefore politically instrumentalized for the purpose of national emancipation and integration, so the process of national unity takes place by religious key (

Jukić 1988, p. 76). That is why it does not have to be quite unbelievable that convinced believers (in our case, Catholics), who should fully accept the teachings of Jesus Christ, are connected with ethnocentrism, xenophobia or racism. Certain papers written so far (

Allport and Kramer 1946;

Batson et al. 1993;

Beatty and Walter 1984;

Blažević Simić 2011;

Jeong 2017;

Malenica 2007) also point to such connection.

However,

Dugandžija (

1986) states that such created relationships should not be interpreted exclusively by intentionally motivated mechanisms but may also be related to some spontaneous manifestations in society. Namely, if we take into account that religion has to satisfy (alongside the individual) set of social functions to be widely accepted, it becomes understandable that it can also substitute the national which often becomes insufficient to itself (

Dugandžija 1986). National life, the author continues, in its specific part has the need to relate to those religious contents that help national survival and development, while religion, on the other hand, can hardly be imagined without relying on national development because it facilitates the maintenance of religion based on its realistic assumptions (

Dugandžija 1986). The impact of religious self-identification and Church attendance on the social distance to Muslims shows the structure of a strong and historically understandable connection, but, in the same way, it warns on the specific dangers arising from this relationship. That is why it is necessary to distinguish the elementary difference between these two aspects because each of their identification leads to the creation of social distance toward Muslims based on prejudices that precede the politicization of religion.

Those prejudices make the Other become suspicious of the bad things in a certain society caused by completely different reasons and features, which leads to stereotypes toward the Other and the different. Therefore, the researched question addressing the relationship with Muslims should be viewed as a problem of relationship with the Other. It is a problem that is present in both Croatia and Europe because as society we still do not accept and do not realize that the Other is different and can have and has different opinions, values, culture and customs.

The results of the research also could be improved by introducing better multicultural education into the curriculum of the Croatian educational system and asking for the potential need to implement (paradigmatical) reforms, in which the key emphasis should be placed on the model and efficiency of the system as well as on the satisfaction of the participants who are key factors. In doing so, efficiency should not be determined (solely) by economic parameters and market laws, but primarily by the humanistic efforts that should direct children on their way to adulthood. A necessary option here is the introduction of new subjects and models of education. It is a necessary to change the paradigm, the approach to the Other.

One of the concepts that should certainly be considered is the concept of transculturalism; a concept that has theoretically overcome the problem of ineffectiveness of multiculturalism, which, given the limitation of individual state-nation, only reproduced the existing state (

Labus 2013). The basic idea of transculturalism is not to undo but to overcome the source and to overcome the established frameworks, giving each person the freedom to be. We are of the opinion that these paradigmatic changes in the educational model would enable us to take into account the contrasts and different horizons as the preconditions for displaying the Other.

The approach of transculturalism offers a completely different view of the concept and the essence of culture.

Labus (

2013) points out that culture is being problematized by the philosophy based on the ontological foundation of human freedom, whereby the only authentic relationship with culture is a creative relation. Transculturality, therefore, helps culture return to its essence—creativity—and transcends all the limits of traditional racial, national and gender limitations of culture; it is “in its universal extension the assumption of the human world” (

Labus 2013, p. 47).

The discussion of transculturality is crucial for human relationships, encounters of cultures, and ultimately the establishment of dialogue as a means of potential reconciliation of different attitudes. If we apply the discussion of transculturality to the relationship between Christians and Muslims, we can notice that, in practice, we are far away from the ideals invoked through this concept. Openness, co-operation, and dialogue with other cultures seem to be too big a bite for today’s Europe, which is increasingly being closed in itself due to the current events.

Rogić (

2017) in his recent review pointed out that this limitation can not be accepted partly because it is, both symbolically and literally, an introduction to the controversial, war-like state. However, Rogić continues, it should be taken into account that after the great immigration wave of the 1960s, European immigration countries saw the formation of comparative societies that strengthen the processes of disintegration in the societies of immigration. To this end, Rogić cites a research by Putnam who analyzed the effects of immigration in a large number of local communities in the United States. The results have shown that great immigration weakens internal trust among members and that such communities find it much more difficult to articulate their common interests and goals. It is therefore essential to understand the complexity of current reality and not to allow “key issues to be covered with ’optimistic’ stereotypes that prevent any critical discussion” (

Rogić 2017).

Moreover, our critical discussion and re-thinking under current social circumstances should also address the often used concepts of democracy, equality and freedom of the individual. We believe that the scientific community should discuss what their meanings are today and what they imply because there seems to be too many different (and contradictory) interpretations and understandings. Freedom as such is a responsibility (and in some way a paradox), and that is something that everyone should first accept; “if I need to be completely free, other people have to accept it, even if my intentions do not agree with their wishes. Thus, the freedom to realize my wishes always reflects on the situation of other people, and this is then reflected on me and on my moral conscience. ⋯ Freedom is general or non-existent; it is always associated with the necessity to compromise—absolute freedom, which simultaneously reconciles both sides, is impossible” (

Bauman 2013).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we want to mention once again that different dimensions of religiosity may have different impacts on social phenomena and thus on the development of distance. Studies have shown that traumatic childhood experiences, insufficient intercultural education, upbringing in single-parent families, life attitudes, (non)existence of contact with minority groups of a particular society may also influence prejudices toward others (

Allport and Kramer 1946). Thus, there are a number of factors that should serve as control variables in the research. Therefore, here, we want once more to emphasize that in our work the influence of religiosity as such has not been investigated, nor its spiritual, experiential or intellectual dimension, nor its consequential influence on individual and social morality. We should bear in mind that mere adherence to religious teachings (i.e., subjective, personal appraisal of it) as well as the continuity of religious practice could become a form without content, especially when they are not accompanied by experiential, intellectual and consequential processes.

As a result, we are aware of the limitations and disadvantages of our own work. This primarily applies to the method and instrument used in the research of such a demanding phenomenon as well as the sample itself. However, the research conducted can be seen as a kind of pilot project, and the results obtained can serve as a basis for further (qualitative) research and as an overview of the situation related to the social distance of students in Split toward Muslims. On the other side, our findings could be of great use to policy makers. Regardless of whether EU macro-policies or micro-policies at the national level are concerned, the form of application should be the same; it should include a series of actions and new research “from above” as this is ultimately one of the tasks of policy-makers—to monitor, analyze and understand the developmental processes of a given society and, in accordance with the results and knowledge gained, to plan and implement developmental strategies that will direct the already present processes.

Finally, we are aware of the difficulties and the problems that lie ahead because of multiple—social, cultural, political, religious and value—intergroup differences. Likewise, we are aware that this paper is by no means a complete or completed whole, but marks the beginning of a search for answers, both to those issues that were defined before conducting the research as well as to the issues this paper has generated in its results and conclusions.

Ultimately, we hope that our research will enrich the literature in the field of sociology of religion and religious (Christian and Muslim) dialogue, help break the stereotypical perceptions and prejudices as well as political instrumentalization of religiosity, not only in the context of distance toward Muslims but also to the Other in general. This is of great importance for all of Europe, but especially for its southeast region.