Stoic Theology: Revealing or Redundant?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Stoic Philosophy and Religious Belief

[The Stoics say] that god is the mind of the world, and that the world is the body of god. (Lactantius, Divine Institutes VII.3 = SVF II. 1041)

The way our bodies are influenced by surrounding bodies is one of the mysteries of human existence, but one that provides the glue that holds entire societies together. We occupy nodes within a tight network that connects all of us in both body and mind.

2. Environmental Ethics in Stoicism

“Now I turn to address you people whose self-indulgence extends as widely as those other people’s greed. I ask you: how long will this go on? Every lake is overhung with your roofs! Every river is bordered by your buildings! Wherever one finds gushing streams of hot water, new pleasure houses will be started. Wherever a shore curves into a bay, you will instantly lay down foundations. Not satisfied with any ground that you have not altered, you will bring the sea into it! Your houses gleam everywhere, sometimes situated on mountains to give a great view of land and sea, sometimes built on flat land to the height of mountains. Yet when you have done so much enormous building, you still have only one body apiece, and that a puny one. What good are numerous bedrooms? You can only lie in one of them. Any place you do not occupy is not really yours.—Seneca’s Letters on Ethics to Lucilius, Letter 89.20.(translated by Graver and Long 2015)

The Anthropocene is a reminder that the Holocene, during which complex human societies have developed, has been a stable, accommodating environment and is the only state of the Earth System that we know for sure can support contemporary society

3. Stoic Theology: A Modern Debate

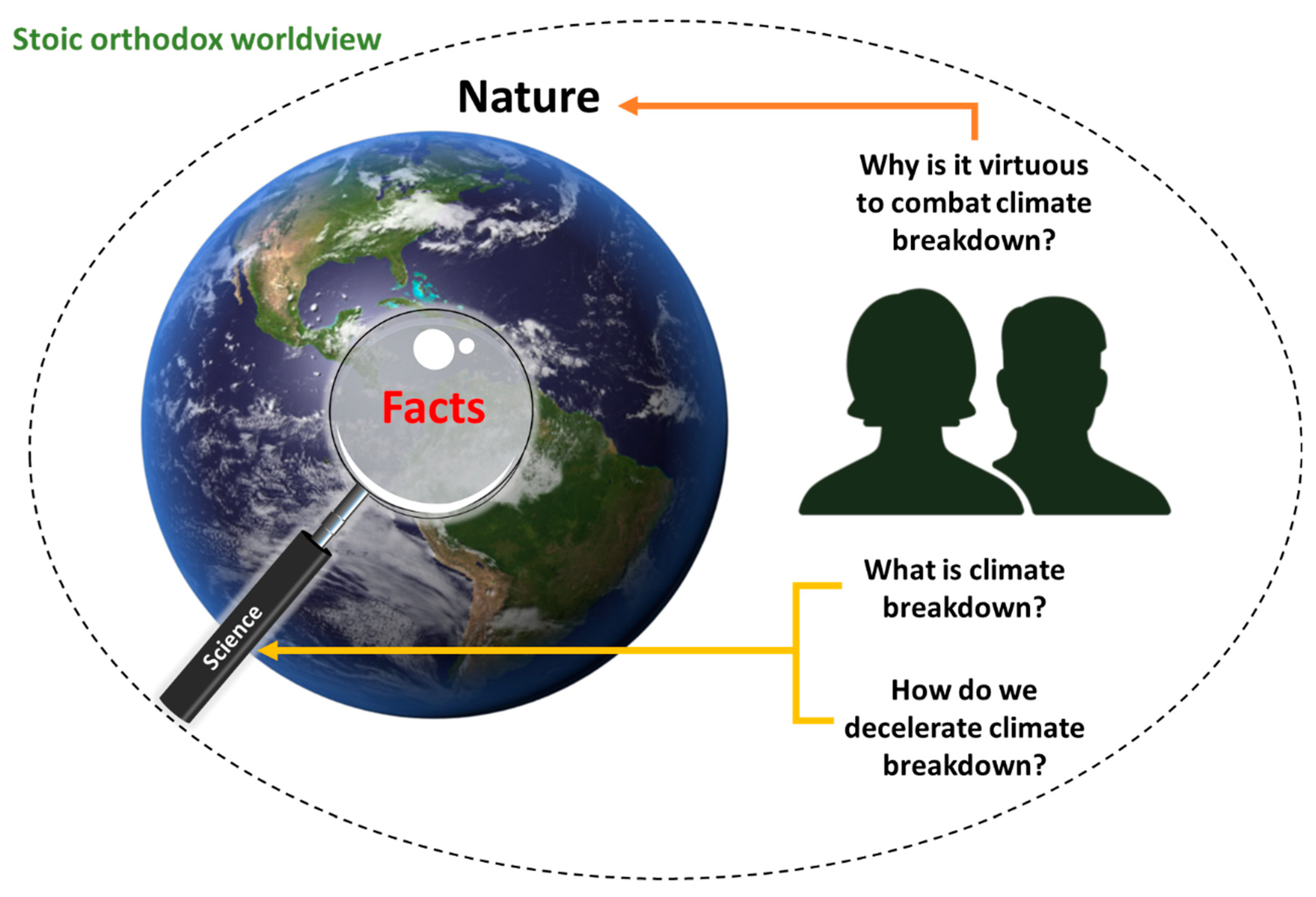

3.1. The Orthodox View

Nor can anyone judge truly of things good and evil, save by a knowledge of the whole plan of nature and even of the life of the gods.

Stoics viewed Nature as benevolent—conducive to human life. Death, disease, and natural disasters are not punishments from an angry God; they are simply the natural unfolding of events within a web of causes, often outside of our control. Stoics accept that the cosmos is as it should be and they face challenging events as opportunities for growth rather than considering them harmful. This is neither resignation nor retreat from the realities of human existence. Stoics strive to do all we can to save lives, cure disease, and understand and mitigate natural and man-made disasters.

3.2. The Heterodox View

Following nature means following the facts. It means getting the facts about the physical and social world we inhabit, and the facts about our situation in it—our own powers, relationships, limitations, possibilities, motives, intentions, and endeavours—before we deliberate about normative matters. It means facing those facts—accepting them for exactly what they are, no more and no less—before we draw normative conclusions from them. It means doing ethics from the facts—constructing normative propositions a posteriori. It means adjusting those normative propositions to fit changes in the facts.

The idea of mind independent moral truths is rejected as incoherent since ethics is the study of human prescriptive actions. Conversely, relativism is also a no starter because there are objective facts about human nature and the human condition that constrain our ethical choices.

If I am convinced that virtue is sufficient for happiness, then when I acquire the cosmic perspective I acquire the thought that this is not just an ethical thesis, but one underwritten by the nature of the universe. But what actual difference can this make? It cannot alter the content of the thought that virtue suffices for happiness, for I understood that before if I understood the ethical theory. Nor is it easy to see how the cosmic perspective can give me any new motive to be virtuous; if I understood and lived by the ethical theory, I already had sufficient motive to be virtuous, and if awareness of the cosmic perspective adds any motivation then I did not already have a properly ethical perspective before.

I do not wish to involve myself in too large a question, and to discuss the treatment of slaves, towards whom we Romans are excessively haughty, cruel, and insulting. But this is the kernel of my advice: Treat your inferiors as you would be treated by your betters. In addition, as often as you reflect how much power you have over a slave, remember that your master has just as much power over you.—Seneca, Moral letters to Lucilius, Letter 47, Chapter 4

4. Stoic Theology: Implications for Environmental Ethics

5. Final Remarks

[We should] get the facts about the physical and social world we inhabit, and the facts about our situation in it—our own powers, relationships, limitations, possibilities, motives, intentions, and endeavours—before we deliberate about normative matters.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Algra, Keimpe. 2003. Stoic theology. In The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics. Edited by Brad Inwood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Annas, Julia. 1995. The Morality of Happiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Annas, John. 2007. Ethics in stoic philosophy. Phronesis 52: 58–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzly, Dirk. 2003. Stoic pantheism. Sophia 42: 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Lawrence C. 1998. A New Stoicism, 1st ed. Princeton University Press: Princeton. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Lawrence C. 2017. A New Stoicism: Revised Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, Marcelo. 2009. Does Cosmic Nature Matter? In God and Cosmos in Stoicism. Edited by Ricardo Salles. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Butman, Jeremy. 2019. Personal Correspondence, January 11. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Christine A., and Ailsa E. Millen. 2008. Studying cumulative cultural evolution in the laboratory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 363: 3529–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, James. n.d. How does the Cosmogony of the Stoics relate to their Theology and Ethics?

- De Waal, Frans. 2010. The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society. New York: Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Devall, Bill. 1995. The Ecological Self. In The Deep Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology. Edited by Alan Drengson and Yuichi Inoue. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dragona-Monachou, Myrto. 1976. The Stoic Arguments for the Existence and the Providence of the Gods. Athens: National and Capodistrian University of Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, Marcus, Laurent CM Lebreton, Henry S. Carson, Martin Thiel, Charles J. Moore, Jose C. Borerro, Francois Galgani, Peter G. Ryan, and Julia Reisser. 2014. Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans: More than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PLoS ONE 9: e111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. 2016. State of the World’s Forests 2016. Forests and Agriculture: Land-Use Challenges and Opportunities. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. 2018. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018: Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Chris. 2016. The Path of the Prokopton—The Discipline of Desire. Available online: http://www.traditionalstoicism.com/the-path-of-the-prokopton-the-discipline-of-desire/ (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Gadotti, Moacir. 2008a. Education for sustainability: A critical contribution to the Decade of Education for Sustainable development. Green Theory and Praxis: The Journal of Ecopedagogy 4: 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadotti, Moacir. 2008b. Education for Sustainable Development: What We Need to Learn to Save the Planet. Sâo Paulo: Instituto Paulo Freire. [Google Scholar]

- Gadotti, Moacir, and Carlos Alberto Torres. 2009. Paulo Freire: Education for development. Development and Change 40: 1255–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Christopher. 2014a. Stoicism and the Environment. In Stoicism Today: Selected Writings. Edited by Patrick Ussher. Exeter: Stoicism Today Project. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Christopher. 2014b. What is Stoic Virtue? In Stoicism Today: Selected Writings. Edited by Patrick Ussher. Exeter: Stoicism Today Project. [Google Scholar]

- Graver, Margaret, and Anthony A. Long. 2015. Seneca: Letters on Ethics: To Lucilius. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haberl, Helmut, K. Heinz Erb, Fridolin Krausmann, Veronika Gaube, Alberte Bondeau, Christoph Plutzar, Simone Gingrich, Wolfgang Lucht, and Marina Fischer-Kowalski. 2007. Quantifying and mapping the human appropriation of net primary production in earth’s terrestrial ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 104: 12942–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hume, David. 2006. An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Illich, Ivan. 1983. Deschooling Society, 1st ed. Harper Colophon: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Inwood, Brad, ed. 2003. The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics, Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, Brad, and Lloyd P. Gerson. 1997. Hellenistic Philosophy: Introductory Readings. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2018. Summary for Policymakers. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, William B. 2008. A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jambeck, Jenna R., Roland Geyer, Chris Wilcox, Theodore R. Siegler, Miriam Perryman, Anthony Andrady, Ramani Narayan, and Kara Lavender Law. 2015. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 347: 768–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedan, Christoph. 2009. Stoic Virtues: Chrysippus and the Religious Character of Stoic Ethics. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Karafit, Steve. 2018. 67: Taking Stoicism Beyond The Self with Kai Whiting in The Sunday Stoic Podcast. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HB1zYYJwBP8&t=1s (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Konstantakos, Leonidas. 2014. Would a Stoic Save the Elephants? In Stoicism Today: Selected Writings. Edited by Patrick Ussher. Exeter: Stoicism Today Project. [Google Scholar]

- Lagrée, Jacqueline. 2016. Justus Lipsius and Neostoicism. In The Routledge Handbook of the Stoic Tradition. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 683–734. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Melissa S. 2012. Eco-Republic: What the Ancients Can Teach Us about Ethics, Virtue, and Sustainable Living. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- LeBon, Tim. 2014. The Argument Against: In Praise of Modern Stoicism. Modern Stoicism. Available online: https://modernstoicism.com/the-debate-do-you-need-god-to-be-a-stoic/ (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- LeBon, Tim. 2018. 6 Years of Stoic Weeks: Have we Learnt so far? Available online: http://www.timlebon.com/Stoic%20Week%202018%20Research%201.0.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Lenart, Bartlomiej. 2010. Enlightened self-interest: In search of the ecological self (A synthesis of Stoicism and ecosophy). Praxis 2: 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, Jeremy. 2017. The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning. New York: Prometheus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold, Aldo. 2014. The land ethic. In The Ecological Design and Planning Reader. Edited by Forster O. Ndubisi. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 108–21. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Michael P. 1994. Pantheism, ethics and ecology. Environmental Values 3: 121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Simon L., and Mark A. Maslin. 2015. Defining the anthropocene. Nature 519: 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Simon L., and Mark A. Maslin. 2018. The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Anthony A. 1968. The Stoic concept of evil. The Philosophical Quarterly 18: 329–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Anthony A., ed. 1996a. Stoic Eudaimonism. In Stoic Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Anthony A. 1996b. Stoic Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Anthony A. 2002. Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Anthony A. 2003. Stoicism in the Philosophical Tradition. In The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics, Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Edited by Brad Inwood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 365–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Anthony A. 2018. Stoicisms Ancient and Modern. Modern Stoicism. Available online: https://modernstoicism.com/stoicisms-ancient-and-modern-by-tony-a-a-long/ (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Long, Anthony A., and David N. Sedley. 1987. The Hellenistic Philosophers: Volume 1, Translations of the Principal Sources with Philosophical Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Greg. 2018. Stoic Fellowship—Current Members 8th November 2018. Personal Correspondence. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock, James E. 1990. Hands up for the Gaia hypothesis. Nature 344: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, Christian. 2016. Stoicism and the Scottish Enlightenment. In The Routledge Handbook of the Stoic Tradition. Edited by John Sellars. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, pp. 254–69. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, George E. 1959. Principia Ethica: (1903). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naess, Arne. 1973. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A summary. Inquiry 16: 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, Arne. 1995. Self-realization. An ecological approach to being in the world. In The Deep Ecology Movement: An Introductory Anthology. Edited by Alan Drengson and Yuichi Inoue. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Daniel W., Andrew L. Fanning, William F. Lamb, and Julia K. Steinberger. 2018. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability 1: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, Huw Parri. 1971. Concepts of Deity. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci, Massimo. 2017a. Becker’s A New Stoicism, II: The Way Things Stand, Part 1. How to Be a Stoic. Available online: https://howtobeastoic.wordpress.com/2017/09/29/beckers-a-new-stoicism-ii-the-way-things-stand-part-1/ (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Pigliucci, Massimo. 2017b. How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life. London: Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci, Massimo. 2017c. What Do I Disagree about with the Ancient Stoics? How to Be a Stoic. Available online: https://howtobeastoic.wordpress.com/2017/12/26/what-do-i-disagree-about-with-the-ancient-stoics/ (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Pigliucci, Massimo. 2018. The Growing Pains of the Stoic Movement. How to Be a Stoic. Available online: https://howtobeastoic.wordpress.com/2018/06/05/the-growing-pains-of-the-stoic-movement/ (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Protopapadakis, Evangelos. 2012. The Stoic Notion of Cosmic Sympathy in Contemporary Environmental Ethics. Antiquity, Modern World and Reception of Ancient Culture, The Serbian Society for Ancient Studies, Belgrade 2012: 290–305. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, Kate. 2017. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Donald. 2017. Did Stoicism Condemn Slavery? Available online: https://donaldrobertson.name/2017/11/05/did-stoicism-condemn-slavery/ (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Rockström, Johan, Will L. Steffen, Kevin Noone, Åsa Persson, F. Stuart Chapin III, Eric Lambin, Timothy M. Lenton, Marten Scheffer, Carl Folke, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, and et al. 2009. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society 14: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosling, Hans. 2010. The Magic Washing Machine. Available online: https://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_and_the_magic_washing_machine (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Sadler, Greg. 2018. Is Stoicism a Religion?—Answers to Common Questions (Stoicism). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sBJOTSFrelA (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Sellars, John. 2006. Stoicism. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, John. 2014. Which Stoicism? In Stoicism Today: Selected Writings. Edited by Patrick Ussher. Exeter: Stoicism Today Project. [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz, Piotr. 2017. Interview with Piotr Stankiewicz. Modern Stoicism. Available online: https://modernstoicism.com/interview-with-piotr-stankiewicz/ (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Steffen, Will, Paul J. Crutzen, and John R. McNeill. 2007. The Anthropocene: Are humans now overwhelming the great forces of nature. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 36: 614–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, Will, Åsa Persson, Lisa Deutsch, Jan Zalasiewicz, Mark Williams, Katherine Richardson, Carole Crumley, Paul Crutzen, Carl Folke, Line Gordon, and et al. 2011. The Anthropocene: From global change to planetary stewardship. Ambio 40: 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, Will, Katherine Richardson, Johan Rockström, Sarah E. Cornell, Ingo Fetzer, Elena M. Bennett, Reinette Biggs, Stephen R. Carpenter, Wim de Vries, Cynthia A. de Wit, and et al. 2015. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347: 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, William O. 1994. Stoic Naturalism, Rationalism, and Ecology. Environmental Ethics 16: 275–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, William O. 2011. Marcus Aurelius: A Guide for the Perplexed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Striker, Gisela. 1996. Following Nature. In Essays on Hellenistic Epistemology and Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 221–80. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, Wilf, Enric Sala, Sean Tracey, Reg Watson, and Daniel Pauly. 2010. The spatial expansion and ecological footprint of fisheries (1950 to present). PLoS ONE 5: e15143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Paul W. 2011. Respect for Nature: A Theory of Environmental Ethics, 25th ed. Princeton University Press: Princeton. [Google Scholar]

- Thunberg, Greta. 2018. School strike for climate—Save the world by changing the rules. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EAmmUIEsN9A (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- UN. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, Kai, and Leonidas Konstantakos. 2018. Stoicism and sustainability. Modern Stoicism. Available online: https://modernstoicism.com/stoicism-and-sustainability-by-kai-whiting-and-leonidas-konstantakos/ (accessed on 7 December 2018).

- Whiting, Kai, Leonidas Konstantakos, Angeles Carrasco, and Luis Carmona. 2018a. Sustainable Development, Wellbeing and Material Consumption: A Stoic Perspective. Sustainability 10: 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, Kai, Leonidas Konstantakos, Greg Misiaszek, Edward Simpson, and Luis Carmona. 2018b. Education for the Sustainable Global Citizen: What Can We Learn from Stoic Philosophy and Freirean Environmental Pedagogies? Education Sciences 8: 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, Kai, Leonidas Konstantakos, Greg Sadler, and Christopher Gill. 2018c. Were Neanderthals Rational? A Stoic Approach. Humanities 7: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. 2018. Living Planet Report–2018: Aiming Higher. Gland: World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Whiting, K.; Konstantakos, L. Stoic Theology: Revealing or Redundant? Religions 2019, 10, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030193

Whiting K, Konstantakos L. Stoic Theology: Revealing or Redundant? Religions. 2019; 10(3):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030193

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhiting, Kai, and Leonidas Konstantakos. 2019. "Stoic Theology: Revealing or Redundant?" Religions 10, no. 3: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030193

APA StyleWhiting, K., & Konstantakos, L. (2019). Stoic Theology: Revealing or Redundant? Religions, 10(3), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030193