Psychological Study of Perceived Religious Discrimination and Its Consequences for a Muslim Population

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

- A scale measuring the perception of religious discrimination in the news media. To our knowledge, there was no scale that specifically measured the perception of religious discrimination in images broadcasted by the news media. That is why we designed this tool by drawing on items developed by Kunst and his colleagues (Kunst et al. 2013; Kunst et al. 2012). Our scale consists of 6 items (e.g., “In the media, Islam is often presented as a threat to French culture”). Three items were put in the negative form so as not to induce bias in participants’ responses (“French media do not portray Muslims as dangerous people”). Participants were asked to rate them on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Thus, a high score on this scale indicates a strong perception of religious discrimination in the news media. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.70.

- An identification scale for the Muslim group consisting of 6 items from Verkuyten’s research (2007). Item 2, “I strongly identify with Muslims”, is an example of these items. This is a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.90.

- The individual self-esteem scale of Rosenberg (1965, quoted by Vallières and Vallerand 1990). A French version of this scale was validated by Vallières and Vallerand (1990). This tool consists of 10 items and participants were invited to answer on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Item 2, “I think I have a number of qualities”, is an example of these items. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for this study is 0.74.

- A perceived stress scale (PSS 10) by Cohen et al. (1983). It was validated in French by Bellinghausen et al. (2009). This tool consists of 10 items including 4 negative items. The participants were asked to evaluate each proposal on its frequency of occurrence during the last month. Item 3, “Last month, how often did you feel nervous and stressed?” is an example of these items. Participants used a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (often). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.89.

- Sociodemographic variables: participants were asked to indicate their religion so that we could make sure that we would only integrate participants who self-identified as Muslims. Age, gender, and place of birth of participants were also taken.

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Operational Hypotheses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

3.3. The Mediating Role of Identification with the Muslim Group in the Relationship between Perceived Religious Discrimination and Individual Variables

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amiraux, Valérie. 2003. Pourquoi parler de discrimination religieuse? Réflexion à partir de la situation des musulmans en France. Confluences Méditerranée 48: 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asal, Houda. 2014. Islamophobie: La fabrique d’un nouveau concept. Etat des lieux de la recherche. Sociologie 5: 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinghausen, Lisa, Julie Collange, Marion Botella, Jean-Luc Emery, and Éric Albert. 2009. Validation factorielle de l’échelle française de stress perçu en milieu professionnel. Santé publique 4: 365–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, David, and Ginette Herman. 2007. Chapitre 3: Au cœur des groupes de bas statut: la stigmatisation. In Travail, chômage et stigmatisation. Edited by Ginette Herman. Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur, pp. 99–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, David, Eleonore Seron, Vincent Yzerbyt, and Ginette Herman. 2006. Perceived Group and Personal Discrimination: Differential Effects on Personal Self-Esteem. European Journal of Social Psychology 36: 773–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, David, Maximilien van Cleempoel, Julie Collange, and Ginette Herman. 2012. Quand le statut du groupe modère les types de discrimination et leurs effets. L’Année Psychologique 113: 575–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscombe, Nyla R., Michael Thomas Schmitt, and Richard Harvey. 1999. Perceiving Pervasive Discrimination Among African Americans: Implications for Group Identification and Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 135–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, James E., and Richard N. Lalonde. 2001. Social Identification and Gender-Related Ideology in Women and Men. British Journal of Social Psychology 40: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Rodney, Norman B. Anderson, Vernessa R. Clark, and David R. Williams. 1999. Racism as a Stressor for African Americans. A Biopsychosocial Model 54: 805–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Sheldon, Tom Kamarck, and Robin Mermelstein. 1983. A global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24: 385–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collectif Contre l’Islamophobie en France. 2016. Rapport 2016. Available online: http://www.islamophobie.net/sites/default/files/Rapport-CCIF-2016.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Commission Fédérale contre le Racisme. 2006. Les relations avec la minorité musulmane en Suisse. Available online: https://www.edi.admin.ch/ekr/dokumentation/00109/index.html (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Commission Nationale Consultative des Droits de l’Homme. 2016. La lutte contre le racisme, l’antisémitisme et la xénophobie. Paris: La documentation française. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, Jennifer, and Brenda Major. 1989. Social Stigma ans Self-Esteem: The Self-Protective Properties of Stigma. Psychological Review 96: 608–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltombe, Thomas. 2005. L’islam imaginaire: la construction médiatique de l’islamophobie en France, 1975–2005. Paris: La Découverte. [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Center on Racism and Xenophobia. 2006. Les musulmans au sein de l’Union Européenne. Available online: http://eumc.europa.eu/ (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Every, Danielle, and Richard Perry. 2014. The Relationship between Perceived Religious Discrimination and Self-Esteem for Muslim Australians. Australian Journal of Psychology 66: 241–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, Vincent. 2012. La « question musulmane » en France au prisme des sciences sociales. Cahiers d’études africaines 206/ 207: 351–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, Azadeh, and Ayşe Çiftçi. 2010. Religiosity and Self-Esteem of Muslim Immigrants to the United States: The Moderating Role of Perceived Discrimination. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjat, Abdellali, and Marwan Mohamm. 2016. Islamophobie: Comment les élites françaises fabriquent le «problème musulman». Paris: La Découverte. First published 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. 2015. Available online: http://www.ipsos.fr/decrypter-societe/2015-01-29-apres-attentats-clarifications-qui-ont-fait-baisser-tensions-sur-l-islam (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Jasperse, Marieke, Colleen Ward, and Paul E. Jose. 2012. Identity, Perceived Religious Discrimination, and Psychological Well-Being in Muslim Immigrant Women. Applied Psychology: An International Review 61: 250–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, Jolanda, Russell Spears, and Antony S. R. Manstead. 1996. Intergroup Norms and Intergroup Discrimination: Distinctive Self-Categorization and Social Identity Effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71: 1222–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jetten, Jolanda, Nyla R. Branscombe, Michael T. Schmitt, and Russell Spears. 2001. Rebels with a Cause: Group Identification as a response to perceived discrimination from the mainstream. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27: 120–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, Nancy, and Stephen Sidney. 1996. Racial Discrimination and Blood Pressure: The CARDIA study of Young Black and White Adults. American Journal of Public Health 86: 1370–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunst, Jonas R., Hajra Tajamal, David L. Sam, and Pål Ulleberga. 2012. Coping with Islamophobia: The Effects of Religious Stigma on Muslim Minorities’ Identity Formation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36: 518–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, Jonas R., David L. Sam, and Pål Ulleberga. 2013. Perceived Islamophobia: Scale development and validation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 37: 225–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, Jonas R., Talieh Sadeghi, Hajra Tahir, David Sam, and Lotte Thomsen. 2016. The Vicious Circle of Religious Prejudice: Islamophobia Makes the Acculturation Attitudes of Majority and Minority Members Clash. European Journal of Social Psychology 46: 249–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagacé, Martine, and Francine Tougas. 2006. Les répercussions de la privation relative personnelle sur l’estime de soi. Les Cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie sociale 1: 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liogier, Raphaël. 2015. Entretien conduit par Haoues Séniguer, « Islamophobie »: Construction et implications. Confluences Méditerranée 95: 143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, Brenda, and Laurie T. O’Brien. 2005. The Social Psychology of Stigma. Annual Review of Psychology 56: 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, Smeeta. 2007. “Saving” Muslim Women and Fighting Muslim Men: Analysis of Representations in the New York Times. Global Media Journal 6: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, Samuel, and Violet Kaspar. 2003. Perceived Discrimination and Depression: Moderating Effects of Coping, Acculturation, and Ethnic Support. Racial/Ethnic Bias and Health 93: 232–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parini, Lorena, Matteo Gianni, and Gaëtan Clavien. 2012. La transversalité du genre: l’Islam et les musulmans dans la presse suisse francophone. Cahier du Genre 52: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, Elizabeth. 2011. Change and Continuity in the Representation of British Muslims Before and After 9/11: The UK Context. Global Media Journal 4: 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, Tom, and Ed Snape. 2006. The Consequences of Perceived Age Discrimination Amongst Older Police Officers: Is Social Support a Buffer? British Journal of Management 17: 167–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Amir. 2007. Media, Racism and Islamophobia: The Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Media. Sociology Compass 1: 443–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Clea. 2010. Systemic Discrimination as a Barrier for Immigrant Teachers. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education 4: 235–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, Michael T., and Nyla R. Branscombe. 2002. The Meaning and Consequences of Perceived Discrimination in Disadvantaged and Privileged Social Groups. European Review of Social Psychology 12: 167–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, Michael T., Nyla R. Branscombe, and Tom Postmes. 2003. Women’s Emotional Response to the Pervasiveness of Gender Discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology 33: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, Michael T., Nyla R. Branscombe, Tom Postmes, and Amber Garcia. 2014. The Consequences of Perceived Discrimination for Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin 140: 921–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, Lori Anderson, Jennifer S. Carmichael, Lauren V. Blackwell, Jeanette N. Cleveland, and George C. Thornton III. 2010. Perceptions of Discrimination and Justice Among Employees with Disabilities. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 22: 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Runnymede Trust. 1997. Islamophobia a Challenge for All of Us. Available online: http://www.runnymedetrust.org/publications/17/32.html (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Vallières, Evelyne F., and Robert J. Vallerand. 1990. Traduction et Validation française-canadienne de l’échelle de l’estime de soi de Rosenberg. International Journal of Psychology 25: 305–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2007. Religious Group Identification and Inter-Religious Relations: A Study Among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 10: 341–57. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyten, Maykel, and Ali Aslan Yildiz. 2007. National (Dis)identification and Ethnic and Religious Identity: A study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33: 1448–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, Bernard, and Mary Kite. 2013. Psychologie des préjugés et des discriminations. Belgique: De Boeck. [Google Scholar]

- Yavari-D’Hellencourt, Nouchine. 2000. « Diabolisation » et « Normalisation » de l’Islam. Une analyse du discours télévisuel en France. In Médias et religion en miroir. Edited by P. Bréchon. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ysseldyk, Renate, Kimberly Matheson, and Hymie Anisman. 2010. Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion from a Social Identity Perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Discrimination | - | 0.342 ** | 0.167 | −0.137 |

| 2. Identification | - | - | 0.069 | −0.459 ** |

| 3. Self-Esteem | - | - | - | −0.116 |

| 4. Perceived Stress | - | - | - | - |

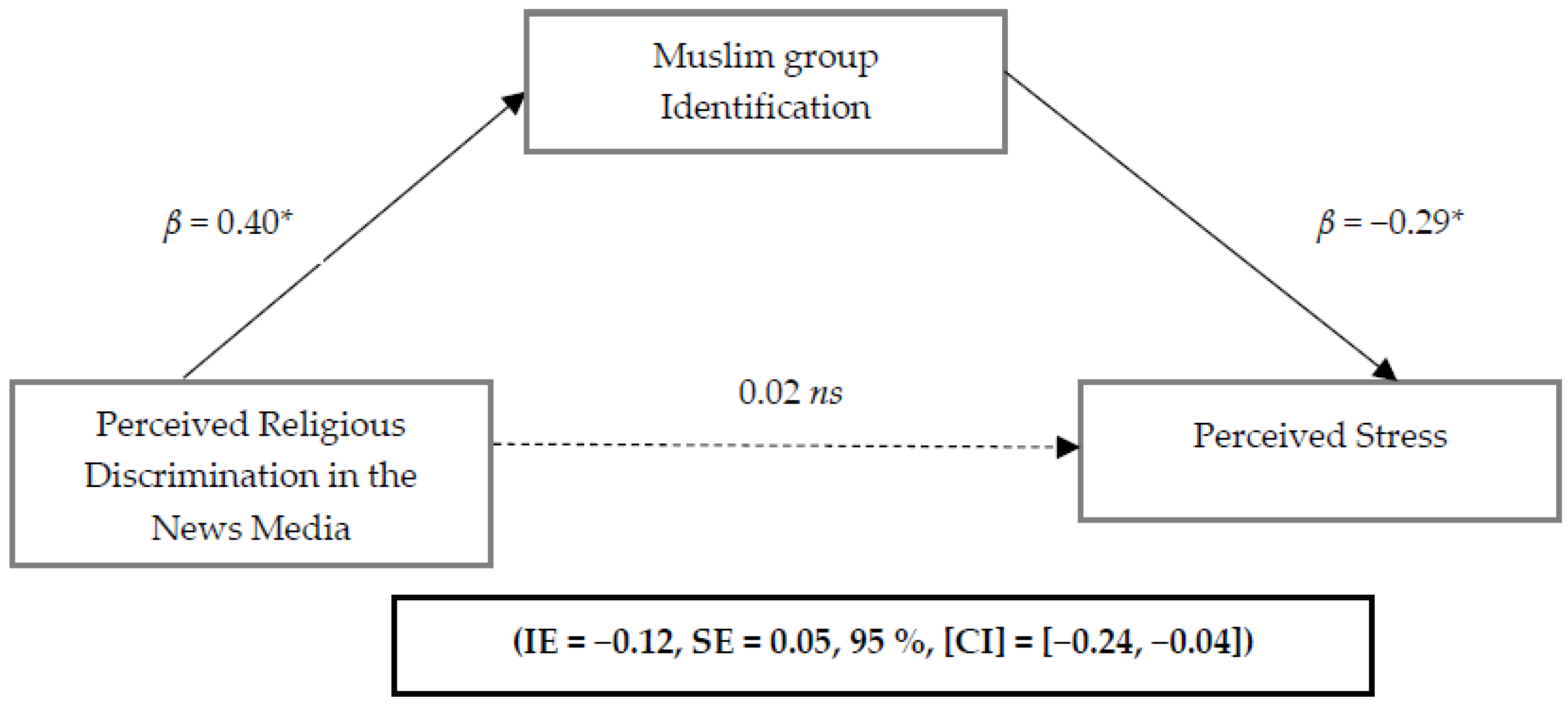

| Bêta | Standard Error | t | p | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 3.69 | 0.72 | 5.15 | 0.001 | 2.26 | 5.11 |

| ZDiscrimination | 0.40 | 0.12 | 3.37 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.64 |

| Model Summary | F(1, 86) = 11.38, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.12, R = 34 | |||||

| Bêta | Standard Error | t | p | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 4.24 | 0.49 | 8.67 | 0.001 | 3.27 | 5.21 |

| ZIdentification | −0.29 | 0.06 | −4.57 | 0.001 | −0.42 | −0.17 |

| ZDiscrimination | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.82 | −0.13 | 0.17 |

| Model Summary | F(2, 85) = 11.39, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.21, R = 46 | |||||

| Effect | Standard Error | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.16 |

| Indirect effect | −0.12 | 0.05 | −0.24 | −0.04 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ameline, A.; Ndobo, A.; Roussiau, N. Psychological Study of Perceived Religious Discrimination and Its Consequences for a Muslim Population. Religions 2019, 10, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030144

Ameline A, Ndobo A, Roussiau N. Psychological Study of Perceived Religious Discrimination and Its Consequences for a Muslim Population. Religions. 2019; 10(3):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030144

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmeline, Anaïs, André Ndobo, and Nicolas Roussiau. 2019. "Psychological Study of Perceived Religious Discrimination and Its Consequences for a Muslim Population" Religions 10, no. 3: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030144

APA StyleAmeline, A., Ndobo, A., & Roussiau, N. (2019). Psychological Study of Perceived Religious Discrimination and Its Consequences for a Muslim Population. Religions, 10(3), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10030144