1. Introduction

In 1875, two Kiowa men, Chê̱thā̀idè (White Horse) and Zó̱tâm (Driftwood), found themselves more than a thousand miles from home and locked indefinitely inside a military prison. Their circumstances stood in stark contrast to their earlier life. White Horse was born in 1847, a time when Kiowas still lived freely on the southern part of the Great Plains (

Petersen 1971, pp. 111–26). His people had political alliances with the Comanche, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. They prospered and boasted some of the largest horse herds on the plains. Kiowas raided for plunder south into Texas and central Mexico and west into New Mexico and Colorado. They played a key role in Indian trade networks that stretched across the vast middle of the United States.

1 Zó̱tâm was born a few years later in 1853 (

Petersen 1971, pp. 171–90). Kiowas still flourished, but they were on the brink of incredible change. That year, Kiowa leaders signed a treaty with American officials. The treaty allowed American traders and explorers to pass through Kiowa lands. It called on Kiowas to curtail their raids into Texas and Mexico. And in one of the treaty’s final provisions, Kiowas agreed to the possibility of the future establishment of a reservation. In 1868, that came to be. Kiowas were among many Native nations up and down the plains who ceded lands in return for peace, cash annuities, and supplies for decades to come. While Kiowas and other Native peoples understood these treaties as a loss, they also hoped to continue their way of life on reservations lands, which while reduced, might still be able to sustain their traditions of hunting and trading and life as an independent people.

But Americans signed these treaties with a different intent. While their desires surely focused on Kiowa lands, I focus here on Americans’ ideas about Native people and what they needed. By 1868, American Protestant reformers had firm ideas about who Indians were and what was required for their survival (

Liebersohn 2016). At the time, Native peoples on the plains lived nomadically. Their food came from hunting and not the more dependable realm of farming. According to reformers, their clothes lacked modesty. Their men were indolent. The women were captured in drudgery. Their children ran wild. Their heathen religion was beyond the pale. Native need was immense. It was material and spiritual. Being Kiowa or a member of any other Plains Indian people was to signify need itself (

Ryan 2003).

By 1875, Chê̱thā̀idè and Zó̱tâm were caught up in a cycle of racialized need and benevolent reformers’ effort to address it. To be sure, they were already living it to some degree. Since 1868, they had lived on a reservation. They interacted with an administrator who not only represented the federal government, but also the Society of Friends, or Quakers. This reservation administrator, or agent, warned them to stay inside reservation boundaries and stop following the buffalo herds. He encouraged them to farm and build wooden houses. He started a school with a Quaker teacher. He brought in a doctor and told Kiowas to avoid their traditional healers. He organized meetings for Christian worship on Sundays. These were the elements of the “white man’s road”.

2 Tensions between Kiowas, their allies, and the Americans grew. In 1874, some of these Native men decided to take up arms and push the Americans out of their lands. Chê̱thā̀idè and Zó̱tâm joined them (

Haley 1985). After months of fighting, the U.S. army suppressed the pan-Indian effort and arrested the Native men involved. Officials decided that at least some of the fighters must face punishment. Like other stories of Native people incarcerated after armed uprisings, Chê̱thā̀idè and Zó̱tâm and were among 72 Plains Indian prisoners of war transported across the country to a military prison called Fort Marion (

Lookingbill 2006).

This prison—the practices inside it and the rhetoric about it—displayed the awesome power white elites had in naming Indian need and articulating its particular correction. Captain Richard Henry Pratt, a veteran of both the Civil War and some of the Indian wars, took charge of the Plains Indian prisoners headed for Fort Marion (

Pratt 2003). He accompanied the men on the trip to the fort. Once there, Pratt decided to run his prison a differently. In the past, Native incarceration mostly functioned to hold prisoners in place, usually until they could be transported by force to a new region or until some sort of physical punishment would be exacted. Pratt, like Protestant reformers involved in the nation’s first prisons, decided to design incarceration at Fort Marion so as to transform his charges. He required the Indians inmates to undergo the cultural transformation that been sought after, but unrealized, on reservations (

Graber 2018, pp. 126–35).

He started on the day of arrival. Pratt directed guards to remove the Indian men’s traditional clothes and replace them with military style uniforms. He also required haircuts. Pratt directed the Native men to perform daily marching drills similar to those performed in military training. Life at the Fort Marion prison also included classes, chapel, periods of labor, and outings into the community. Local women taught the prisoners to read and write. Pratt preached in the chapel. The inmates worked a variety of odd jobs, carrying luggage for tourists, picking oranges, and digging wells (

Pratt 2003).

Americans traveling to Saint Augustine for the mild weather also visited the prison. They had only praise for what they saw inside. Their praise reflected the rhetoric of racialized need developed decades earlier. Lizzie Champney, a travel writer and visitor to Fort Marion, described the Indian men as “the most bloodthirsty of their race”, “savages in dress, in behavior, and in instinct” (

Champney 1876). In a letter to the editors of the

New York Daily Tribune, Episcopal bishop and reformer, Henry Whipple, called the inmates “sullen, revengeful, full of hate” (

Pratt 2003, p. 163). The famous abolitionist and novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe told her readers that the Indian men had been sent to Fort Marion for being the “wildest, most dangerous, and most untamable of the tribes” (

Stowe 1877). According to these visitors, who were also prominent Christian reformers, Native men were incapable of peaceful living. Their need was immense.

That need, according to these observers, was addressed at Fort Marion. Captain Pratt accomplished a tremendous transformation. Champney observed that the Native inmates sang hymns, said the Lord’s Prayer, and practiced temperance. She delighted that “noble Christian ladies” worked diligently to educate them (

Champney 1876). Stowe marveled that the Native men were no longer “savages”. They wore uniforms, kept their barracks clean, attended prayer meetings, and earned money by working. Stowe claimed inmates had “use of a new set of faculties” (

Stowe 1877).

Despite their efforts to paint a vivid picture of life at Fort Marion, Champney, Whipple, and Stowe never featured words spoken by inmates. They also avoided the terms “prison” or “prisoners” in their descriptions. They, along with other benevolent reformers, extolled Captain Pratt’s experiment at Fort Marion while avoiding any mention of the site as a prison and its occupants as residing there against their will. Take, for example, a conversation recorded at an 1877 Quaker meeting on Indian affairs. The committee praised the good reports coming out of Fort Marion. They were pleased to hear that Native men had two hours of classes, including Bible lessons, every day. They also approved of the manual labor regime. Unlike many other writings on Fort Marion, the Quaker leaders acknowledged the situation as an example of “confinement,” but insisted, “there is little to no suffering” (

Associated Executive Committee of Friends of Indian Affairs 1872–1882).

There was one person, at least, who called Fort Marion what it was: a military prison. That person was Richard Henry Pratt. Although Pratt maintained relationships with some of the most prominent Christian reformers in the country, he was a military man at heart. Because he worked with army colleagues who called for the extermination of Native people, Pratt had no need to avoid reference to the role force and coercion played in his prison experiment. He acknowledged it during his time running Fort Marion and later when he reflected back on it for his memoir (

Pratt 2003).

Coercion was part of daily life at Fort Marion. He required cultural transformation and used force to make it happen. It started with clothes. When guards distributed military uniforms, the Native men apparently took liberties to alter them. Some cut up the pants in order to create Plains-style leggings. Pratt had none of it. He recalled the incident in his memoir. He wrote that the Indian men who tried to make leggings received “immediate correction” (

Pratt 2003, p. 118).

Pratt had one his most dramatic challenges from Chê̱thā̀idè, one of the Kiowa prisoners mentioned above. Chê̱thā̀idè, along with a few other Kiowa men, planned an escape from Fort Marion. The plot included a request by Chê̱thā̀idè to leave the prison in order to pray on a nearby hillside. Pratt heard rumors of the plot and confronted the other Kiowa prisoners, who admitted to the plan, including their vow to die rather than remain in prison. Pratt sent officers with bayonets to apprehend Chê̱thā̀idè. Pratt then chained him inside the guardhouse and drugged him. The other prisoners initially thought Pratt had killed him. While Chê̱thā̀idè eventually woke from his drugged slumber, he was shackled and confined for more than a month. No one else tried to escape Fort Marion (

Pratt 2003, pp. 147–51).

Pratt openly reported on the disciplinary issues he faced and his use of force to deal with them. Indeed, he argued that force was necessary to address the particular needs of Indians in their “savage” state. In an article about him published years later, the writer described Pratt’s approach to “wild Indians” in need of “preliminary training” before they could be “passed into the mild hands of the missionary teacher” (

Will the Indian Stay Civilized? n.d.). “Routine teaching”, the writer continued, “did not do the regenerative work for these once fierce savages. It was the influence of a clear-headed, strong man with power at his back and Christian sympathy in his heart.” Pratt’s prison regime presumed that “savage” Indians required “preliminary training.” They needed a strong man in a secure environment to use his power. Native people needed prison. Only there could missionaries later bring them the Christian gospel and Anglo-American civilization.

Even as Pratt named Indians’ particular need and emphasized that the “savage” race required coercive handling, Christian boosters of Fort Marion proclaimed their praise. Some Quakers reflected on Pratt’s program of preliminary training and concluded that the army captain’s work among Native people was “a labor of love” and “nothing short of the mighty transforming power of God could have brought about so great a change” (

Miles to Pratt 1878). Other benevolent reformers were equally generous with their praise. A New York reformer referred to the Native inmates as Pratt’s “flock” and described them as “prodigal” sons that had been “found” (

Burnham to Pratt 1879;

Burnham 1878). Bishop Whipple argued that even the “most savage men” “can be reached by discipline, kindness, and Christian teaching” (

Pratt 2003, p. 164). Reflecting on the transformation wrought at Fort Marion, Whipple concluded that Pratt had provided the Indian men with “in its best sense, a Christian school.”

The same Protestant reformers cheered Pratt on when he decided to follow-up his Fort Marion experiment with a Native American boarding school organized along similar principles. In 1879, Pratt opened the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and traveled the country to enroll Native children and youth. Similar to Fort Marion, Pratt required his students to undergo cultural transformation: American clothes, haircuts, labor and English-speaking. When children resisted this regime, they faced corporal punishment (

Adams 1995).

2. The Sanctification of Native Incarceration

America’s first experiments with incarceration—starting in the 1790s and growing into the 1830s and 1840s—corresponded with what has been called the Age of Benevolence. The leading citizens who built and ministered within New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts prisons engaged in a host of other reforming activities, creating what scholars have often called the Benevolent Empire (

Cayton 2010). They started Sunday schools, served as agents for the American Bible Society, promoted colonization for African Americans, and organized campaigns for the relief of the poor. They were tirelessly involved in the nation’s first prisons, sites they lobbied for, designed, and sometimes administered with the goal of reforming inmates through a highly mediated period of incarceration (

Graber 2011).

The Christian reformers that populated the Benevolent Empire were busy people. They performed a remarkable amount of public service to address the great need they saw around them. Literary scholar Susan Ryan has called us to pay careful attention to the “need” benevolent reformers recognized in others and addressed through their activism. She argues that benevolence proved to be a site in which elite Americans worked out national, as well as racial identities (

Ryan 2003, pp. 1–5). Donors were true citizens in their ability to sustain themselves and also provide for others. Recipients, on the other hand, revealed their inability to make it in this geographically and economically expanding new nation. They were people in need (

Ryan 2003, pp. 5–8).

Ryan has shown how benevolent reformers came to see need not just in the individuals they assisted, but in entire groups of people. According to them, she writes, “the categories of blackness, Indianness, and Irishness…came to signify need itself” (

Ryan 2003, p. 1) In this way, elite Americans “raced” need, ascribing essential difference to the populations whose situations they sought to relieve. The result was an enduring distance. Black need and Indian need made these populations different from self-sufficient white Americans. But this ascribed need also resulted in enduring ties. White Americans felt duty-bound to address the need exhibited in racial others (

Ryan 2003, p. 5).

While Ryan did not address prisons or punishment directly, her analysis of how need came to be raced can help us understand the connection between Christianity, race, and mass incarceration. It makes sense of why benevolent reformers praised not only Pratt’s prison at Fort Marion, but also the Carlisle school and other off-reservation boarding institutions for Native children. Ryan showed how antebellum reformers came to view certain racial and ethnic groups as typifying need. This construction of need tied reformers to these particular populations, but also authorized unequal power relationships and coercive interventions. Pratt openly named the raced form of need that he and others associated with American Indians. Left to their own devices on the plains, Native peoples would carry on their doomed way of life. Pratt was forthright about what sort of response this need required. It required force and coercion. It demanded constraints on freedom.

Protestant reformers, on the other hand, accepted the circumstances and power relationships that Pratt described, but never acknowledged them openly. Consider the Quaker committee members who insisted that no suffering occurred at Fort Marion. Rather than dwelling on how ideas of need shaped power relationships, they instead emphasized need as the basis for their sentimental bonds with Native people. They extolled the “noble Christian ladies” who taught classes to the Indian men. They referred to Pratt as a shepherd with a flock. They understood the “power” Pratt exhibited as a “strong man” as an example of the “mighty transforming power of God.” In doing so, Pratt’s prison became an ordinary classroom. A warden became a doting father. Officials who threatened with weapons and punished with drugs and solitary confinement became associated with the very work of God. Pratt claimed that Native people needed prison. Reformers accepted his claim, avoided discussion of the prison’s dehumanizing aspects, and then asserted that Fort Marion was God’s way of working with needy American Indians.

Understanding how need came to be raced, how force was required to address that need, and how Christian benevolent reformers tiptoed around the realities of coercion, helps us understand contemporary American prisons. As Winnifred Sullivan and Tanya Erzen have shown, the dominant model for Christian interaction with incarcerated people is conservative Protestant FBMs or faith-based ministries (

Sullivan 2009;

Erzen 2017). These scholarly works, along with my own experiences in prison ministries, convince me that FBMs speak the same language about incarcerated people and what they need. They tell stories about prisoners (who are disproportionally black and brown) that emphasize incarcerated peoples’ sorry state prior to incarceration and involvement in faith-based ministries. They focus on the things FBMs make available: counseling, education, support, and connection. They praise prison staff who accommodate FBM programs. They testify to lives transformed and attribute the change to God’s power realized through these programs. According to narratives circulated by FBMs, prisons are sites for needy (and racialized) groups of people to experience God’s amazing work. FBMs are the new Richard Pratt. Present-day prisons are the new Fort Marion.

3. Drawing Other Worlds at Fort Marion

Neither Pratt nor the benevolent reformers who supported him included Native prisoners’ own expressions in their publications, but not because they were unaware of them. Indeed, white officials and visitors to Fort Marion noticed and encouraged Native prisoners’ steady output of drawings. Works by Chê̱thā̀idè (White Horse) and Zó̱tâm (Driftwood) offer useful examples. At Fort Marion, they confronted a regime designed to address what leading Americans considered to be their particular needs. They underwent Pratt’s “preliminary training”. They responded in several ways, including Chê̱thā̀idè’s escape plot. They also drew. Their artistic production addressed the racialized renderings of their need, their “preliminary training” through incarceration, and offered up an alternative vision of what it meant to be Kiowa.

As noted earlier, Chê̱thā̀idè and Zó̱tâm were born into the Kiowa nation at a time of flourishing. They were raised among men who displayed their accomplishments in myriad visual forms. They depicted battles and visions on tipi covers (

Ewers 1978). They adorned their bodies with colors, objects, and weapons given to them in dreams and other supernatural encounters (

Greene 1997;

McCoy 2003). When they got to Fort Marion, they used the materials around them to recall their lives in a state of freedom. Kiowas and other Native prisoners from the southern Plains drew hundreds of pictures during their three-year incarceration (

Berlo 1996;

Petersen 1971;

Szabo 1993;

Wong 1989).

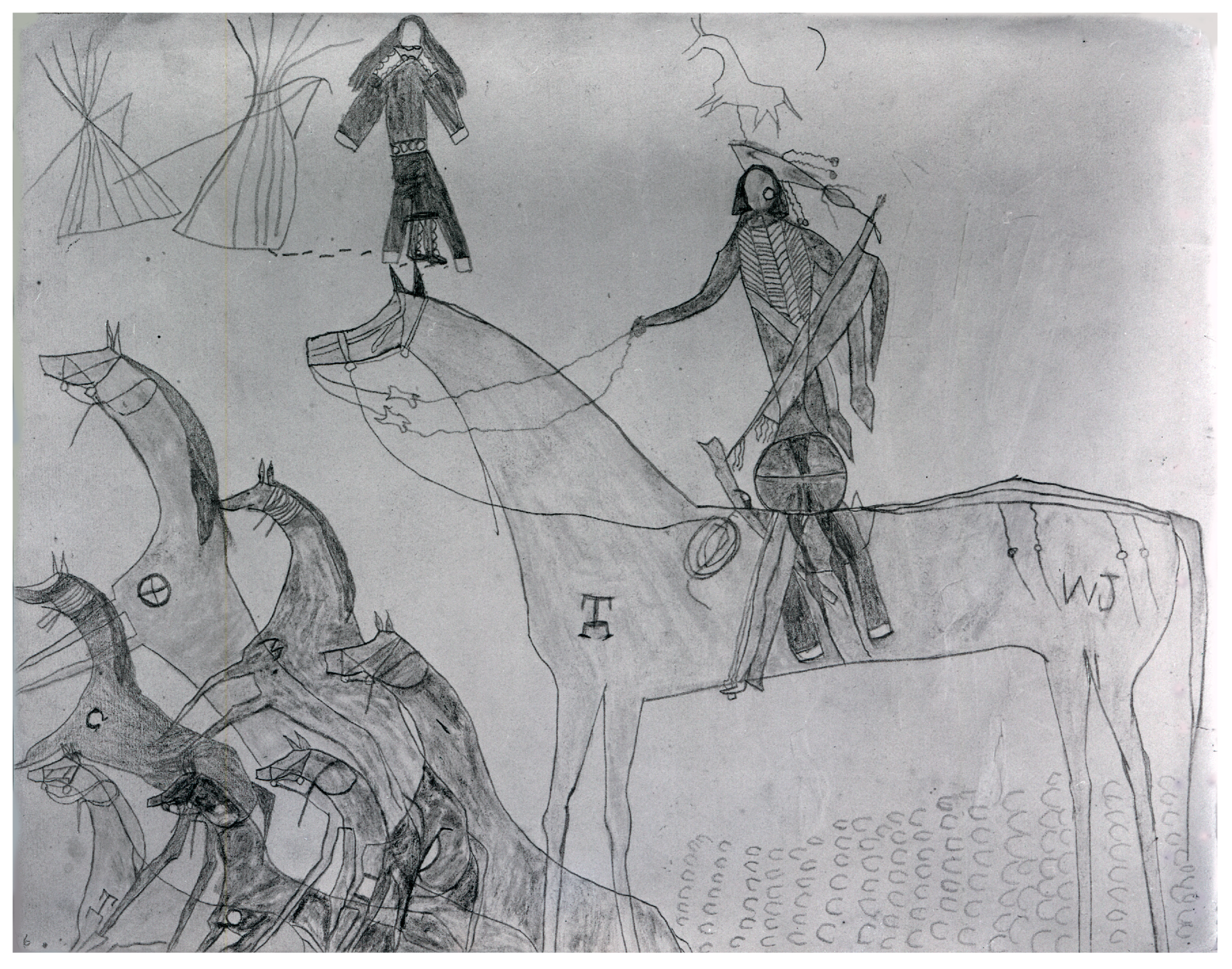

Chê̱thā̀idè, for instance, drew pictures of himself as a warrior and raider. (

Figure 1) Above the male figure is what art historians call a name glyph. The glyph is a white horse, denoting Chê̱thā̀idè’s name and identifying him as the subject of the picture. In his drawings, Chê̱thā̀idè depicted himself in moments of strength, as in this drawing in which he captures many ponies. In another, he draws himself as the owner of a powerful shield. (

Figure 2) Attached at his hip, the shield includes a geometric design, likely received in a vision or inherited from another powerful leader. In Kiowa culture, decorated shields were understood to be imbued with sacred power. In the next example, he leads other men out on an expedition, most likely a raid for animal resources or to battle. (

Figure 3) And lastly, he stands with other prominent leaders to give a speech. (

Figure 4) If Pratt and benevolent reformers understood him to be a potent symbol of racialized need, Chê̱thā̀idè depicted himself as a man of dignity and power.

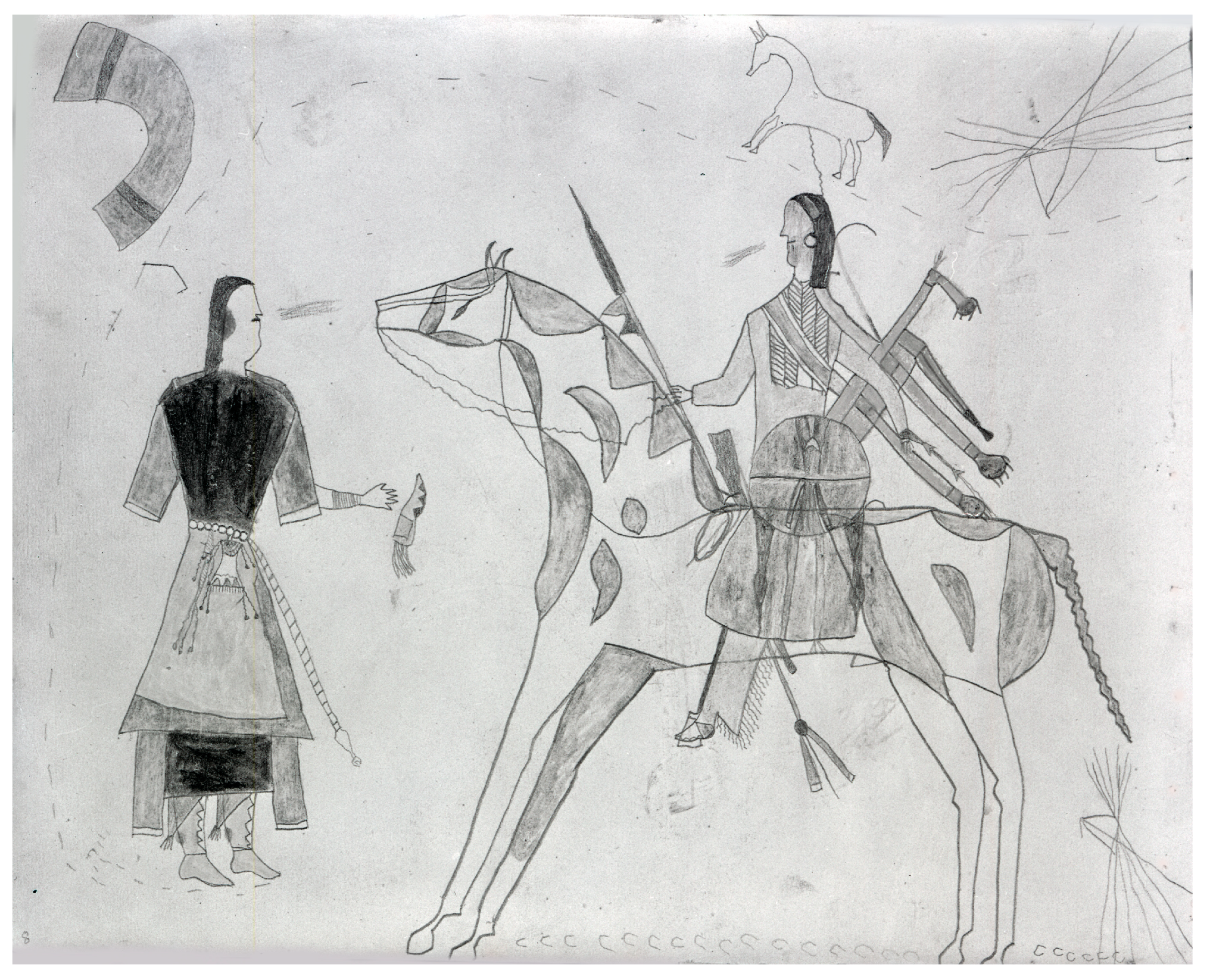

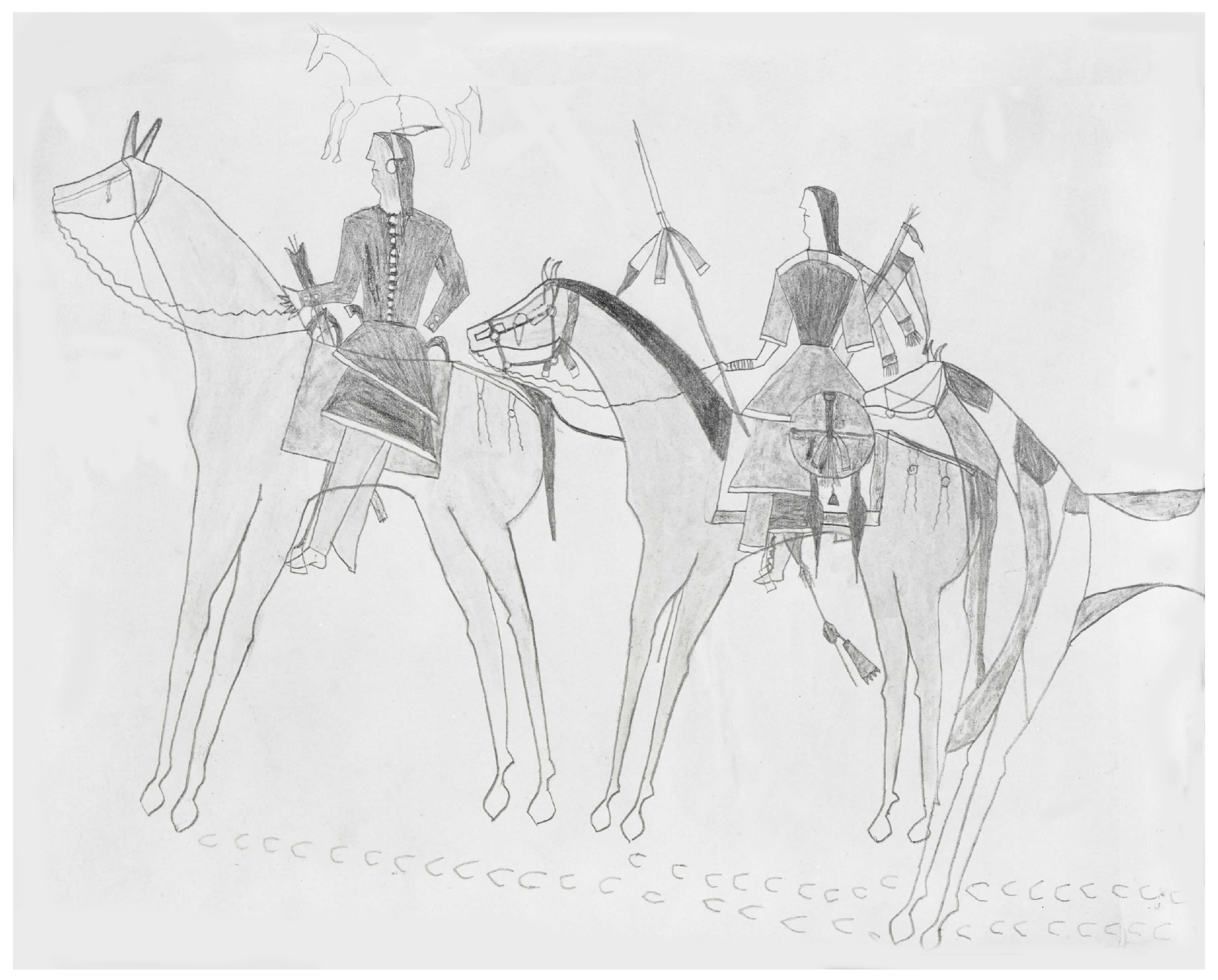

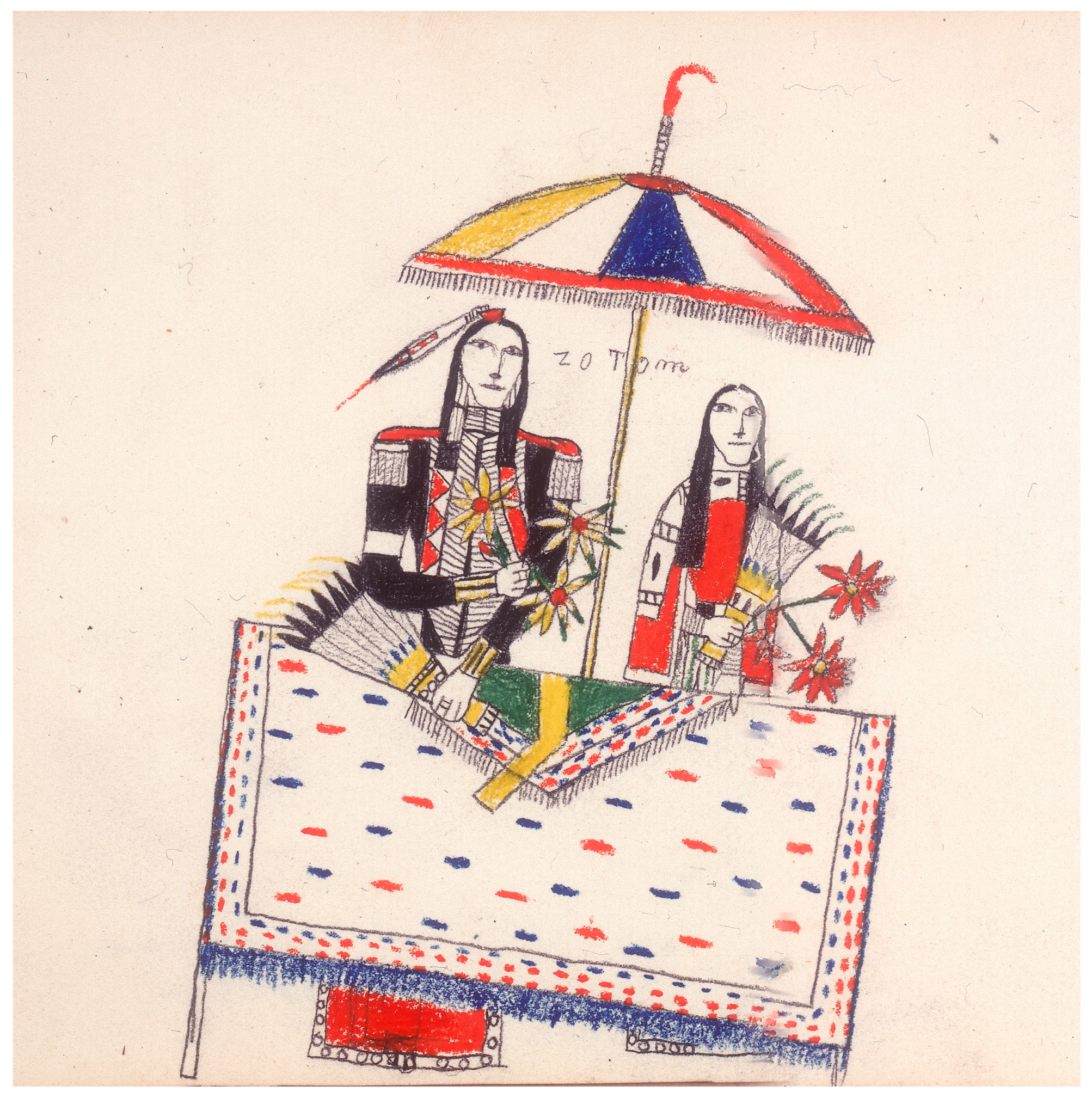

Zó̱tâm also represented powerful Kiowa men in images of hunting, diplomacy, and war. After learning to write at Fort Marion, Zó̱tâm used an Anglicized version of his name to identify himself in his drawings. He drew himself engaged in meeting an American army official during important negotiations in 1871. (

Figure 5) His images also depicted his family life prior to incarceration, including this drawing of himself and his wife. (

Figure 6) Like Chê̱thā̀idè, Zó̱tâm produced pictures in which he presented himself as a strong man and leader of his family and nation.

3 Unlike Chê̱thā̀idè, Zó̱tâm also depicted life at Fort Marion. The contrasts with life in freedom could not be greater. He drew Indian prisoners adorned in American uniforms being forced to practice military drills. (

Figure 7) In other drawings, he noted prison guards carrying weapons and monitoring the Native men’s movements. He also depicted the local women who taught language classes to the prisoners. (

Figure 8) Again, the uniforms stand in stark contrast to the individualized adornment featured in drawings about pre-prison life. Zó̱tâm also drew chapel services in which inmates crammed together and listened to their warden, Captain Pratt, preach sermons on Sundays. (

Figure 9).

Chê̱thā̀idè and Zó̱tâm, along with other southern Plains Indian men incarcerated at Fort Marion, created images depicting the reality Pratt described. The imprisoned artists detailed their cultural transformation through “preliminary training.” They showed how coercion and threat functioned as part of the process. They revealed the forced labor, high walls, and loaded guns that facilitated Pratt’s vision. The artists and their work show us how Bishop Whipple and his fellow reformers were wrong. This was not just a Christian school. These were not just meetings for prayer. By racializing need and obscuring the workings of power, benevolent reformers made prison for some people inevitable and desirable. They gave racialized incarceration the Lord’s sanction.