Moon, Rain, Womb, Mercy The Imagery of The Shrine Model from Tell el-Far‛ah North—Biblical Tirzah For Othmar Keel

Abstract

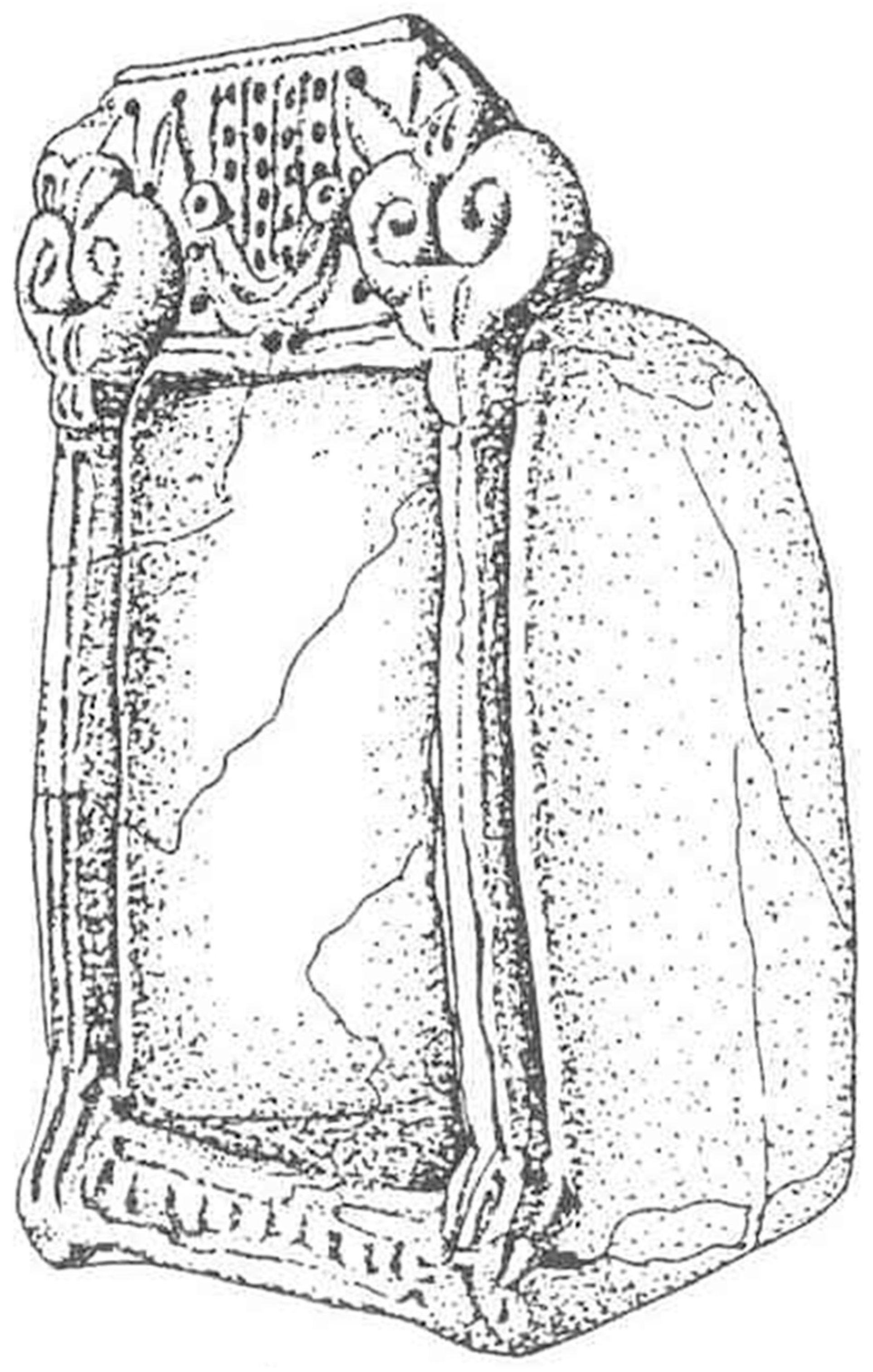

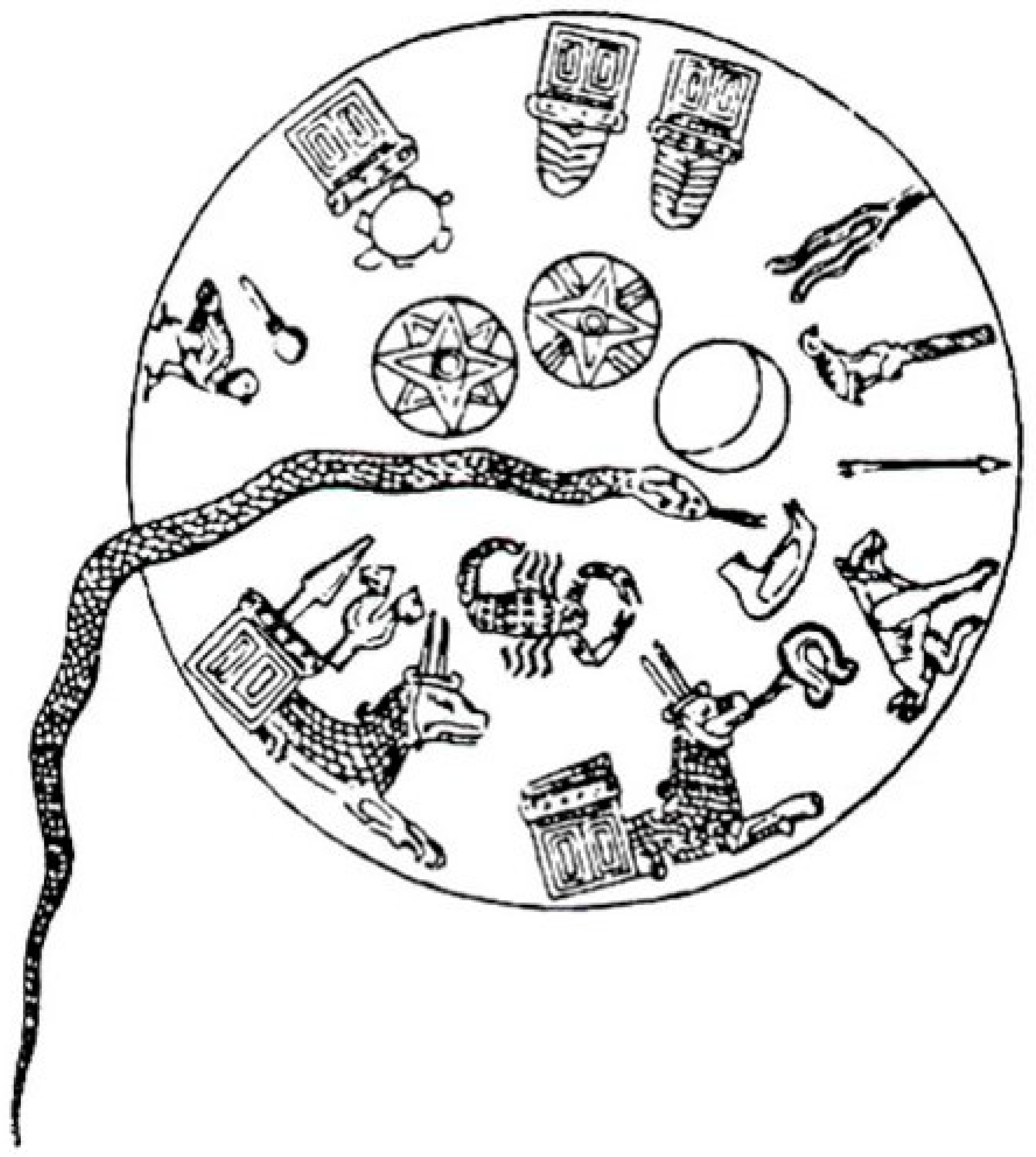

:1. Previous Interpretations

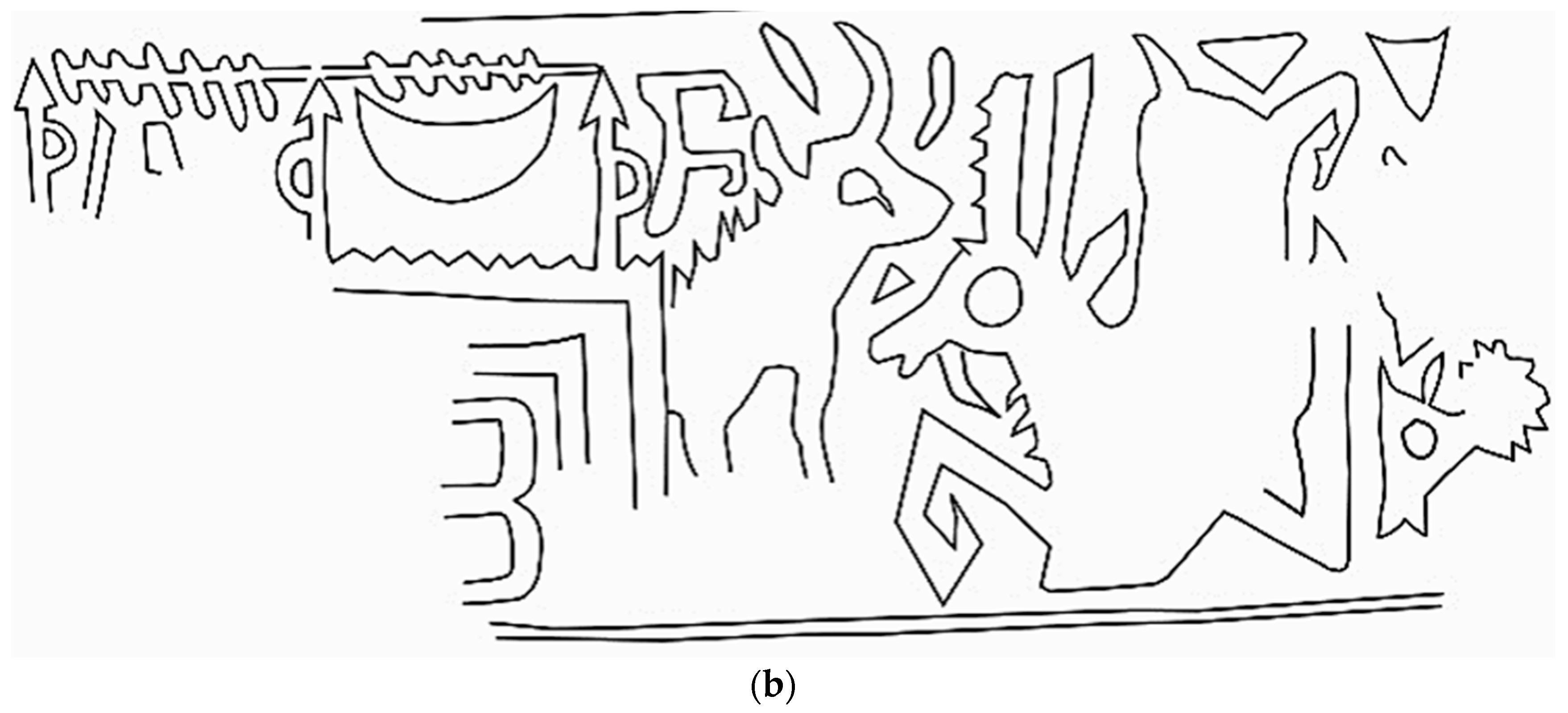

2. Suggested Reading of Motifs

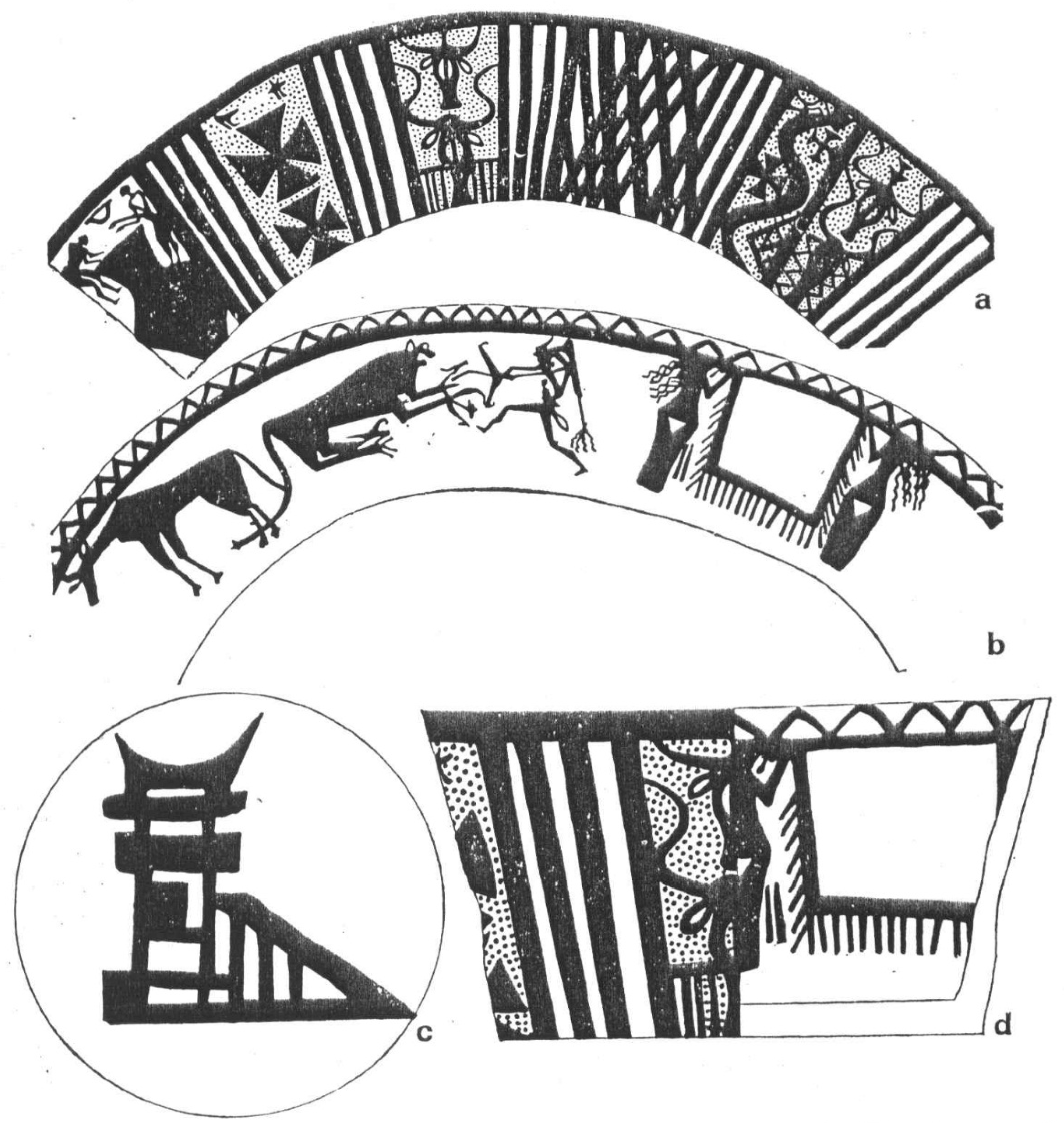

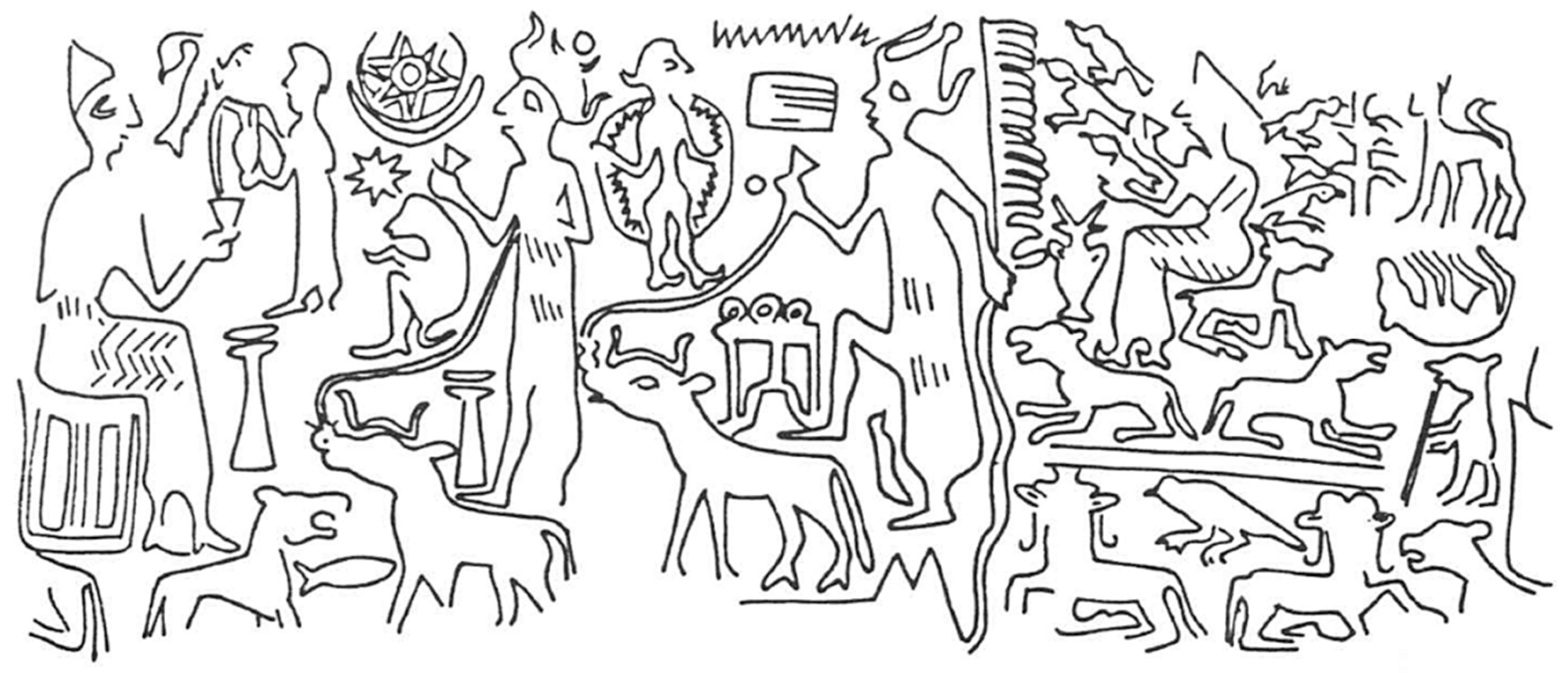

2.1. Rain Imagery in the Ancient Near East

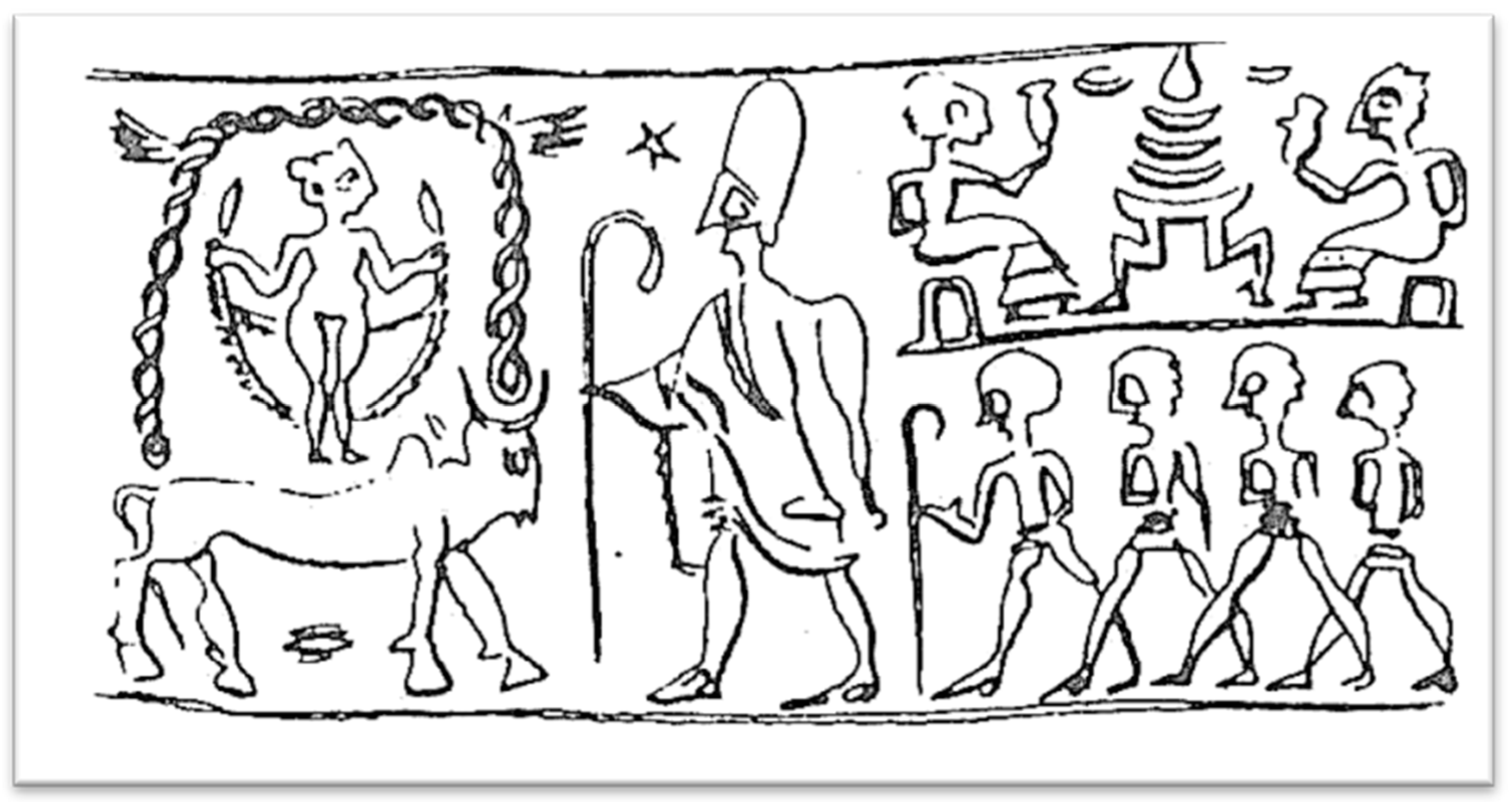

2.2. Moon Imagery, Womb and Compassion

3. The Tell el-Far‛ah Shrine Model: Meaning and Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amiet, Pierre. 1960. Le temple ailé. Revue d’Assyriologie 54: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Attinger, Pascal. 1993. Eléments de linguistique sumérienne. La Construction de du11/e/di “dire”. OBO Sonderband. Fribourg: Editions universitaire. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Bartelmus, Rüdiger. 2001. Šāmajim—Himmel. Semantische unde traditionsgeschichtliche Aspekte. In Das Biblische Weltbild und Seine Altorientalischen Kontexte. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 32. Edited by Bernd Janowski and Beate Ego. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 87–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Josef, Robert K. Englund, and Manfred Krebernik. 1998. Mesopotamien—Späturuk Zeit und Frühdynastische Zeit Annährungen 1. OBO 160/1. Edited by Pascal Attinger and Markus Wäfler. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Pirhiya. 2002. Imagery and Representation. Studies in the Art and Iconography of Ancient Palestine: Collected Essays. Edited by Nadav Naʼaman, Uza Zevulun and Irit Ziffer. Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University Occasional Publications 3. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Berkheij-Dol, J. 2012. Sacred or Prophane? Identifying Cultic Places in the Early Iron Age Southern Levant. A Study on the Pillared Courtyard-Building of Tel Kinrot and Its Shrine Model. Ph.D. dissertation, Protestant Theological University Kampen, Kampen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Bernett, Monika, and Othmar Keel. 1998. Mond, Stier und Kult am Stadtor. OBO 161. Freiburg: Universitäverlag, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Dominique. 2001. Emar IV Les Sceaux: Mission archéologique de Meskéné-Emar Recherces au pays d’Aštata. (OBO SA 20). Fribourg: Editions Universitaires, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Jeremy, and Anthony Green. 1992. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer, Rainer Michael. 1965. Die Entwicklung der Glyptik während der Akkad-Zeit. Untersuchungen zur Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 4. Berlin: der Gruyter & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner-Traut, Emma. 1970. Das Muttermilchkrüglein: Ammen mit Stillumhang und Mondamulett. WdO 5: 145–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chambon, Alain. 1984. Tell el-Far‛ah I: L’âge du Fer. “Mémoire” no 31. Paris: Éditions recherché sur les Civilisations. [Google Scholar]

- Collon, Dominique. 1975. The Seal Impressions from Tell Atchana (Alalakh). AOAT 27. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchner Verlag and Verlag Butzon & Bercker Kevelaer. [Google Scholar]

- Collon, Dominique. 1987. First Impressions. Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Collon, Dominique. 1992. The Near Eastern Moon God. In Natural Phenomena. Their Meaning, Depiction and Description in the Ancient Near East. Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen Verhandelingen, Afd. Letterkunde, Nieuwe Reeks, deel 152. Edited by Diederik J. W. Meijer. Amsterdam, Oxford and New York: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Edward M. 2015. Dictionary of Qumran Aramaic. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Couto-Ferreira, Maria Erica. 2014. She Will Give Birth Easily: Therapeutic Approaches to Chilbirth in 1st Millennium BCE Cuneiform Sources. Dynamics 34: 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalley, Stephanie, and Beatrice Teissier. 1992. Tablets from the Vicinity of Emar and Elsewhere. Iraq 54: 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasen, Veronique. 2003. Les amulettes d’enfants dans le monde gréco-romain. Latomus 62: 275–89. [Google Scholar]

- Daviau, P. M. Michele. 2008. Ceramic Architectural Models from Transjordan and the Syrian Tradition. In Proceedings of the 4th ICAANE, Berlin 2004. Edited by Hartmut Kühne, Rainer Maria Czichon and Florian Janoscha Kreppner. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 294–308. [Google Scholar]

- Del Olmo Lete, Gregorio, and Joaquín Sanmartín. 2003. A Dictionary of the Ugaritic Language. Translated by W. G. E. Watson. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Delougaz, Pierre. 1968. Animals Emerging from a Hut. JNES 27: 184–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, William G. 2016. Archaeology and Ancient Israelite Iconography: Did Yahweh Have a Face? In Proceedings of the 2nd ICAANE Copenhagen 2000. Edited by Ingolf Thuesen. Bologna and Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Donner, Herbert, and Wolfgang Röllig. 2002. Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften 1. 5., erweiterte und überarbeitete Auflage. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Erbele, Dorothea. 1999. Gender Trouble in the Old Testament. Three Models of the Relation between Sex and Gender. SJOT 13: 131–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fales, Mario, and Roswitha Del Fabbro. 2017. Mankind and the Gods in Mesopotamia. In Signs before the Alphabet. Journey to Mesopotamia at the Origins of Writing. Edited by Adriano Favaro. Exhibition Catalogue, Palazzo Lorendan, Venice. Venice: Giunti Editore, pp. 141–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Daniel E. 2000. Time at Emar. The Cultic Calendar and the Rituals from the Diviner’s House. Mesopotamian Civilizations 11. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort, Henri. 1944. A Note on the Lady of Birth. JNES 3: 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, Yosef. 2018. Chasing Away Lions and Weaving: The Longue Durée of Talmudic Gender Icons. In Sources and Interpretations in Ancient Judaism. Studies for Tal Ilan at Sixty. Edited by Meron Piotrowski, Geoffrey Herman and Saskia Dönitz. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Golani, Amir. 2013. Jewelry from the Iron Age II Levant. OBO SA 34. Fribourg: Academic Press, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Goldwasser, Orly, and Colette Grinevald. 2012. What Are “Deteminatives” Good For? In Lexical Semantics in Ancient Egyptian. Edited by Eitan Grossman, Stéphane Polis and Jean Winand. Lingua Aegyptia Studia Monographica 9. Hamburg: Wiedmayer, pp. 17–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hijara, Ismail, R. N. I. B. Hubbard, and J. P. N. Watson. 1980. Arpachiyah, 1976. Iraq 42: 131–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, Wayne. 2012. Sunday in Mesopotamia. In Living the Lunar Calendar. Edited by Jonathan Ben-Dov, Wayne Horowitz and John M. Steele. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hunger, Hermann. 2009. Schaltmonat. Reallexikon der Assyriologie 12: 130–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, David. 2016. The Crescent-Lunate Motif in the Jewelry of the Bronze and Iron Ages Ancient Near East. In Proceedings, 9th ICAANE I, Basel 2014. Edited by Rolf L. Stucky, Oskar Kaelin and Hans-Peter Mathys. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 137–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. 1976. The Treasures of Darkness. A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. 1987. The Harps that Once … Sumerian Poetry in Translation. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jasmin, Michaël. 2013. Tell el-Far‛ah (N). In The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Archaeology. Edited by Daniel M. Master. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Jastrow, Marcus. 1903. A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature I. London: Luzac & Co., New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Jenni, Ernst, and Claus Westermann. 1976. Theologisches Handwörterbuch zum Alten Testament II. Müncehn: Kaisreverlag, Zürich: Theologischer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, Thomas Muir. 1977. Ḥarsūsi Lexicon. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor, Helene J., and Pinhas Delougaz. 1996. Choga Mish I The First Five Seasons of Excavations 1961–1971 Part 2: Plates. Oriental Institute Publications 101. Edited by Abbas Alizadeh. Chicago: The oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Hava. 2016. Portable Shrine Models. Ancient Architectural Clay Models from the Levant. BAR International Series 2791. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, Othmar. 1980. Das Böcklein in der Milch seiner Mutter und Verwandtes. OBO 33. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

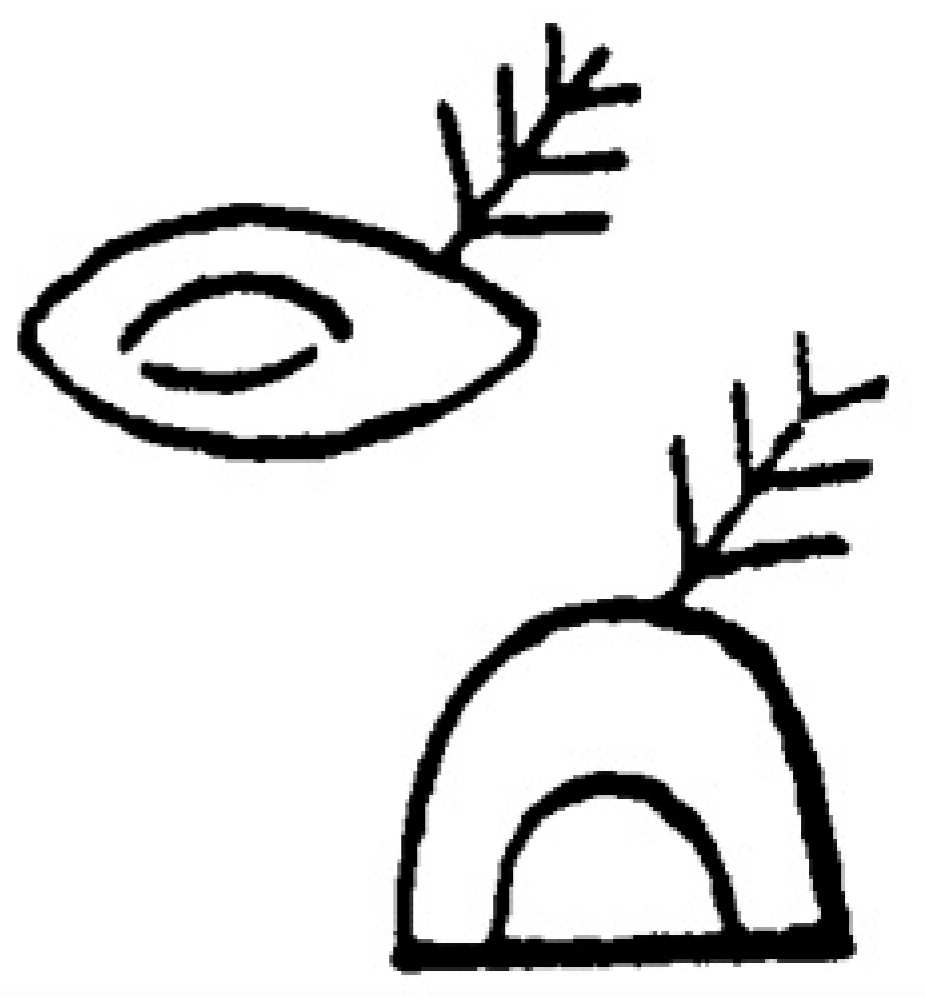

- Keel, Othmar. 1989. Die Ω-Gruppe. Ein mittelbronzezeitlicher Stempelsiegel-Typ mit erhabenem Relief aus Anatolien, Nordsyrien und Palästina. In Studien zu den Stempelsiegeln aus Palästina/Israel II. OBO 88. Edited by Othmar Keel, Hildi Keel-Leu and Silvia Schroer. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 39–87. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, Othmar. 2010. Corpus der Stempelsiegel-Amulette aus Palästina/Israel von den Anfängen bis zur Perserzeit III: Von Tell el-Far‛ah Nord bus Tell el-Fir. OBO SA 31. Fribourg: Academic Press, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, Othmar, and Chr Uehlinger. 1992. Göttinen, Götter und Gottessymbole. Neue Erkentnisse zur Religionsgeschichte Kanaans und Israels aufgrund bislang unerschlossener ikonographischer Quellen. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman, Assaf. 2018. Comments on the Archaeology and History of Tell el-Far‛ah North (Biblical Tirzah) in the Iron Age IIA. Semitica 60: 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz. 2015. Clay Shrine Model. In Yavneh II: The ‘Temple Hill’ Repository Pit. OBO SA 36. Edited by Raz Kletter, Irit Ziffer and Wolfgang Zwickel. Fribourg: Academic Press, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Koehl, Robert B. 2016. The Ambiguity of the Minoan Mind. In Metaphysis. Ritual, Myth and Symbolism in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 15th International Aegean Conference, Vienna, 2014. Aegeum 39. Edited by Eva Alram-Stern, Fritz Blakolmer, Sigrid Deger-Jalkotzy, Robert Laffineur and Jörg Weilhartner. Leuven and Liege: Peeters, pp. 469–78. [Google Scholar]

- Krebernik, Manfred. 1995. Mondgott. A. Reallexikon der Assyriologie 8: 360–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Wilfred G. 1985. Trees, Snakes and Gods in Ancient Syria and Anatolia. BSOAS 48: 435–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Wilfred G. 1987. Devotion: The Language of Religion and Love. In Figurative Language in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Murray Mindlin, Markham J. Geller and John E. Wansbrough. London: Routledge, pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Leinwand, Nancy. 1992. Regional Characteristics in the Styles and Iconography of the Seal Impressions of Level II at Kültepe. JANES 21: 141–72. [Google Scholar]

- Leslau, Wolf. 1991. Comparative Dictionary of Ge‛ez. Classical Ethiopic. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Baruch A. 2002. ‘Seed’ versus ‘Womb’: Expressions of Male Dominance in Biblical Israel. In Sex and Gender in the Ancient Near East. Proceedings of the XLVIIe Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. Edited by Simo Parpola and Robert M. Whiting. Helsinki: Helsinki Institue for Asian and African Studies University of Helsinki, pp. 337–43. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Christl. 2014. Körperlich und emotionale Aspekte JHWHs aus der Genderperspektive. In Göttliche Körper—Göttliche Gefühle: Was leisten anthropomorphe und anthrpopathische Götterkonzepte im Alten Orient und im Alten Testament. OBO 270. Edited by Andreas Wagner. Fribourg: Academic Press, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 171–89. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, Donald M. 1990. Principles of Composition in Near Eastern Glyptic of the Later Second Millennium B.C. OBO SA 8. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Opificius, Ruth. 1984. Die geflügelte Sonne. Himmels- und Regendarstellungen im alten Vorderasien. UF 16: 189–236. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 2015. Religious Practices and Cult Objects during the Iron Age II at Tell Reḥov and their Implications regarding the religion in Northern Israel. HeBAI 4: 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mazar, Amihai. 2016. Discoveries from the early Monarchic period at Tel Reḥov. In It Is the Land of Honey. Discoveries from Tel Reḥov, the Early Days of the Israelite Monarchy. Exhibition Catalogue. Edited by Irit Ziffer. Tel Aviv: MUSA, Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv, pp. 9e–68e. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Béatrice. 2002. Les “maquettes architecturales” du Proche-Orinet ancien. Mésopotamie, Syrie, Palestine du III au millieu du Ier millénaire avant J.-C. I. Bibliothèque Archaeologique et Historique 160. Beyrouth: Institut Français d’archéologie du Proche-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Na’aman, Nadav. 2007. Royal Inscriptions versus Prophetic Story: Mesha’s Rebellion according to Biblical and Moabite Historiography. In Ahab Agonistes. The Rise and Fall of the Omri Dynasty. Library of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 421. Edited by Lester L. Grabbe. London and New York: T & T Clark, pp. 145–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ornan, Tallay. 2001. The Bull and its Two Masters: Moon and Storm Deities in Relation to the Bull in the Ancient Near East. IEJ 51: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ornan, Tallay. 2007. Labor pangs: The Revadim plaque type. In Images as Sources. Studies on Ancient Near Eastern Artefacts and the Bible Inspired by the Work of Othmar Keel. OBO Special Volume. Edited by Susanne Bickel, Silvia Schroer, René Schurte and Christoph Uehlinger. Fribourg: Academic Press, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 215–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ornan, Tallay, Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah, and Benjamin Sass. 2017. A Governor of the City Seal Impression from the Western Wall Plaza Excavations in Jerusalem. Qadmoniot 50: 100–3. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, Adelheid. 2016. Much more than just a Decorative Element: The Guilloche as Symbol of Fertility. In Mille et une Empreints. Un Alsacien en Orient. Mélanges en l’honneur du 65e anniversaire de Dominique Beyer. Subartu XXXVI. Edited by Julie Patrier, Philippe H. Quenet and Pascal Butterlin. Tournhout: Brepols, pp. 379–93. [Google Scholar]

- Özgüç, Nimet. 1965. The Anatolian Group of Cylinder Seal Impressions from Kültepe. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. [Google Scholar]

- Özgüç, Nimet. 1987. Samsat Mühürleri. Belleten 51: 429–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pardee, Dennis. 2002. Ritual and Cult at Ugarit. Writings from the Ancient World 10. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, Holly. 2012. Glyptic Art of Konar Sandal South, Observations on the Relative and Absolute Chronology in the Third Millennium BCE. In Nāmvarnāmeh. Papers in Honor of Massoud Azarnoush. Edited by Hamid Fahimi and Karim Alizadeh. Tehran: Iran Negar, pp. 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rendsburg, Gary A. 1983. Hebrew RḤM = “Rain”. VT XXXIII: 357–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rendsburg, Gary A. 2009. Israelian Hebrew Features in Deuteronomy 33. In Mishneh Todah. Studies in Deuteronomy and Its Cultural Environment in Honor of Jeffrey H. Tigay. Edited by Nili Sacher Fox, David A. Glatt-Gilad and Michael J. Williams. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 167–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rochberg, Francesca. 1996. Personifications and Metaphors in Babylonian Celestial Omina. JAOS 116: 475–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochberg, Francesca. 2010a. In the Path of the Moon. Babylonian Celestial Divination and Its Legacy. Studies in Ancient Magic and Divination 6. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

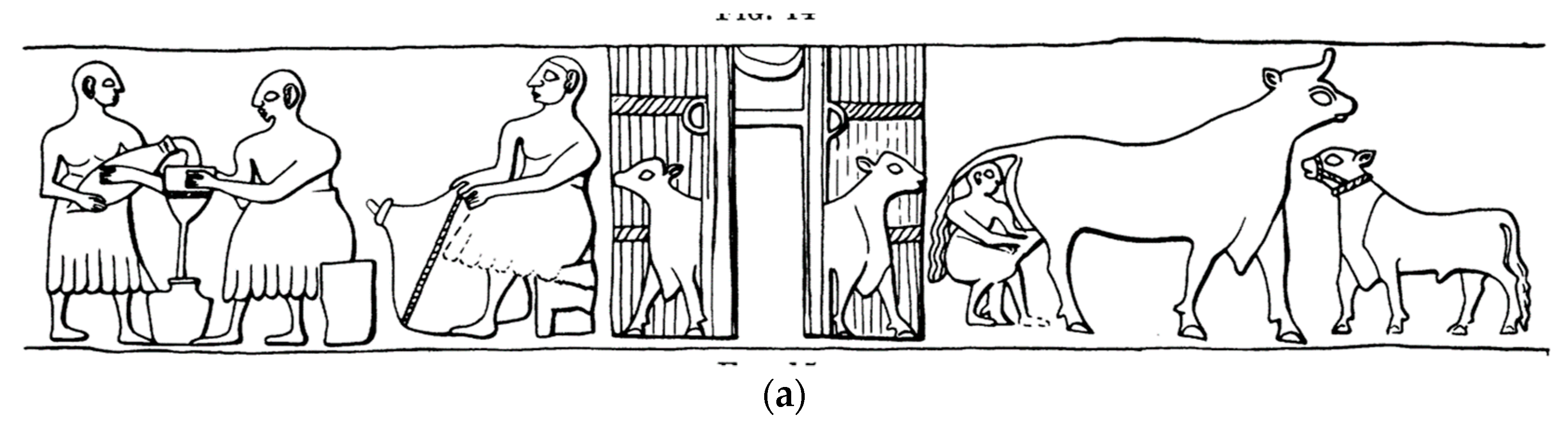

- Rochberg, Francesca. 2010b. Sheep and Cattle, Cows and Calves: The Sumero-Akkadian Astral Gods as Livestock. In Opening the Tablet Box. Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Benjamin R. Foster. Culture and History in the Ancient Near East 42. Edited by Sarah Melville and Alice Slotsky. Leiden: Brill, pp. 347–459. [Google Scholar]

- Rochberg, Francesca. 2016. Before Nature. Cuneiform Knowledge and the History of Science. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schroer, Silvia. 2018. Die Ikonographie Palästina/Israels und der Alte Orient 4: Die Eisenzeit bis zum begin der achäminidischen Herrschaft. Basel: Schwab. [Google Scholar]

- Schwemer, Daniel. 2006. Šāla. A. Philologisch. Reallexikon der Assyriologie 11: 565–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schwemer, Daniel. 2008. The Storm Gods of the Ancient Near East: Summary, Synthesis, Recent Studies. Part 1. JANES 7: 121–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, Ursula. 1989. Die altbabylonische Kudurru-Reliefs. Symbole Mesopotamischer Gottheiten. OBO 87. Freiburg: Universitätsverlag, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Sharvit, Shimon. 1972. New Light on Eḥad Mi Yodea. Bar-Ilan Journal 9: 475–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg, Åke W., and Eugen S. J. Bergamann. 1969. The Sumerian Temple Hymns. Locust Valley: J. J. Augustin. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Mark S. 1997. The Baal Cycle. In Ugaritic Narrative Poetry. SBL Writings from the Ancient World 9. Edited by Simon B. Parker. Atlanta: Scholars Press, pp. 61–180. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Mark. 2006. The Rituals and Myths of the Feast of the Goodly Gods of KTU/CAT 1.23. SBL Resources for Biblical Studies 51. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, Michael. 1990. A Dictionary of Jewish Palestinian Aramaic in the Byzantine Period. Dictionary of the Talmud, Midrash and Targum II. Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, Michael. 2009. A Syriac Lexicon. Translation from the Latin, Correction, Expansion and Update of C. Brockelmann’s Lexicon Syriacum. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, Piscataway: Gorgias. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, John M. 2011. Making Sense of Time: Observational and Theoretical Calendars. In The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. Edited by Karen Radner and Eleanor Robson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 470–85. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Diana L. 1988. Mythologische Inhalte der Nuzi-Glyptik. In Hurriter und Hurritisch. Edited by Volkert Haas. Konstanzer Altorientalische Symposien II. Konstanz: Universitäts Verlag Konstanz GmBH, pp. 173–209. [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, Ulrike. 2017. Cows, Women and Wombs. Interrelations Between Text and Images from the Ancient Near East. In From the Four Corners of the Earth. Studies in the Iconography and Cultures of the Ancient Near East in Honour of F.A.M. Wiggermann. AOAT 441. Edited by David Kertai and Olivier Nieuwenhuyse. Münster: Ugarit Verlag, pp. 205–58. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkeller, Piotr. 2016. Nanna/Suen, the Shining Bowl. In Libiamo ne’ lieti calici. Ancient Near Eastern Studies Presented to Lucio Milano on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday by Pupils, Colleagues and Friends. AOAT 436. Edited by Paola Corò, Elena Devecchi, Nicla De Zorzi and Massimo Maiocchi. Münster: Ugarit, pp. 615–25. [Google Scholar]

- Stol, Marten. 1992. The Moon as Seen by the Babylonians. In Natural Phenomena. Their Meaning, Depiction and Description in the Ancient Near East. Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen Verhandelingen, Afd. Letterkunde, Nieuwe Reeks, deel 152. Edited by Diederik Jacobus Willem Meijer. Amsterdam, Oxford and New York: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, pp. 245–75. [Google Scholar]

- Stol, Marten. 2000. Birth in Babylonia and the Bible. Its Mediterranean Setting. Cuneiform Monographs 14. Groningen: Styx. [Google Scholar]

- Suter, Claudia E. 2000. Gudea’s Temple Building. The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler in Text and Image. Cuneiform Monographs 17. Groningen: Styx. [Google Scholar]

- Tal, Abraham. 2000. A Dictionary of Samaritan Aramaic. Leiden, Boston and Köln: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- van der Toorn, Karel. 1999. Goddesses in Early Israelite Religion. In Ancient Goddesses: The Myths and the Evidence. Edited by Lucy Goodison and Christine Morris. London: British Museum Press, pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- van der Toorn, Karel. 2002. The Use of Images in Israel and the Ancient Near East. In Sacred Time, Sacred Place. Archaeology and the Religion of Israel. Edited by Barry M. Gittlen. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

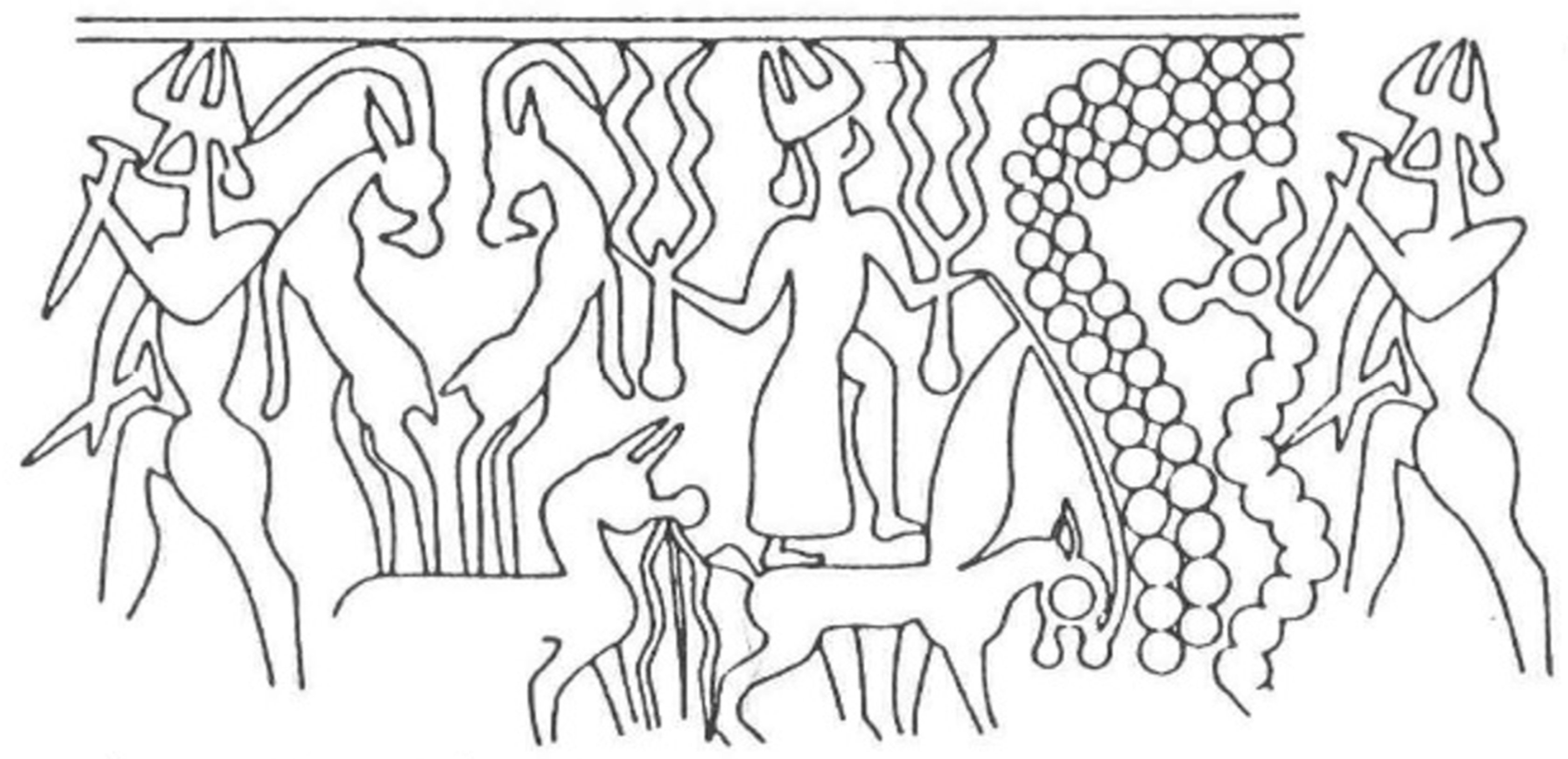

- van Loon, Maurits. 1990. The Naked Rain Goddess. In Resurrecting the Past. A Joint Tribute to Adnan Bounni. Uitgaven van het Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul 67. Edited by P. Matthiae, M. van Loon and H. Weiss. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, pp. 363–79. [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, Maurits. 1992. The Rainbow in Ancient Asian Iconography. In Natural Phenomena. Their Meaning, Depiction and Description in the Ancient Near East. Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen Verhandelingen, Afd. Letterkunde, Nieuwe Reeks, deel 152. Edited by Diederik Jacobus Willem Meijer. Amsterdam, Oxford, New York and Tokyo: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sceinces, pp. 149–68. [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis, Niek. 1991. A Cow of Sîn. Library of Oriental Texts 2. Groningen: Styx. [Google Scholar]

- Verderame, Lorenzo. 2014. The Halo of the Moon. In Divination in the Ancient Near East. A Workshop on Divination Conducted During the 54th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Würzburg, 2008. Edited by Jeanette Fincke. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wehr, Hans. 1980. A Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic. Beirut: Librarie du Liban, London: MacDonald & Evans Ltd. [Google Scholar]

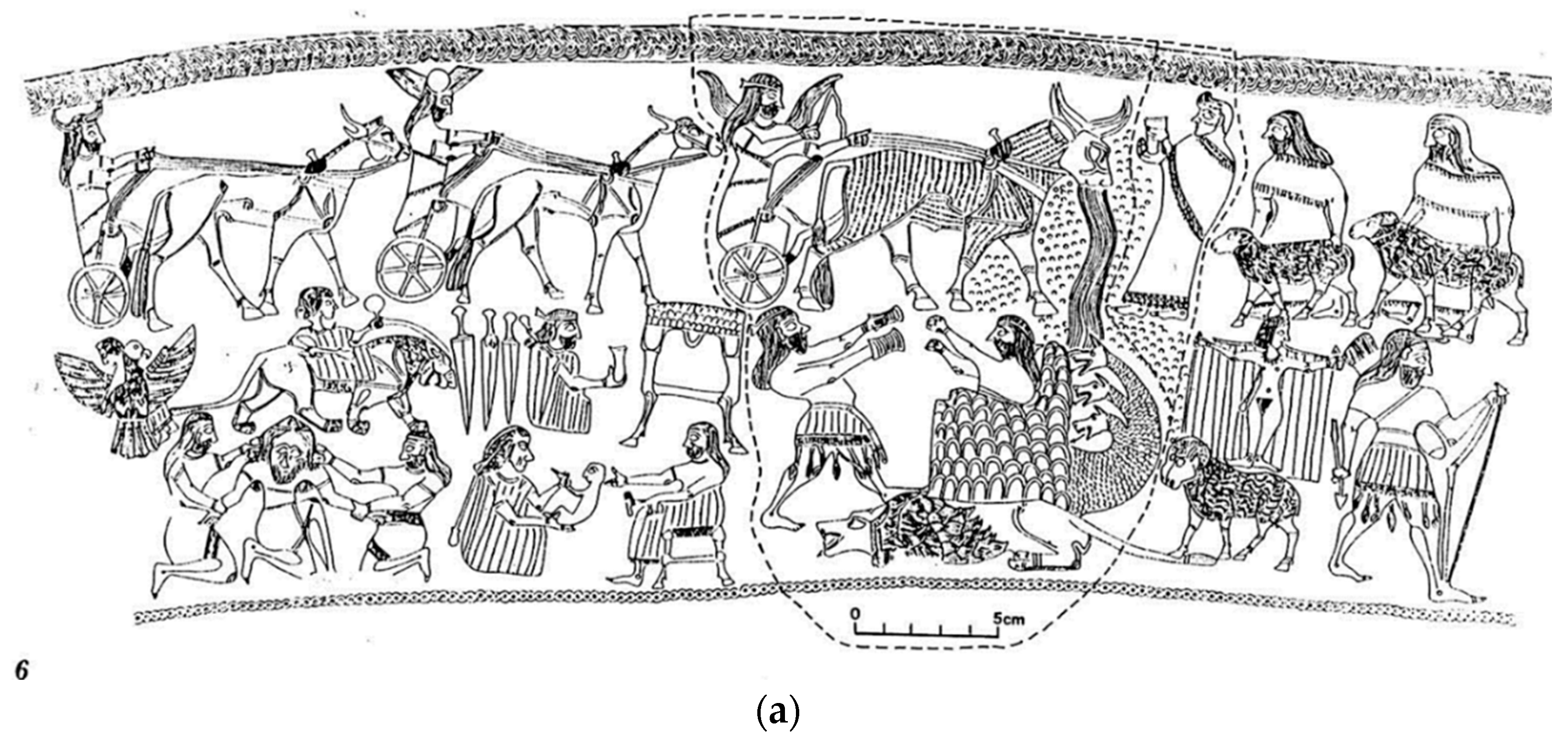

- Winter, Irene. 1989. The “Hasanlu Gold Bowl”: Thirty Years Later. Expedition 31: 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, C. Leonard. 1934. Ur Excavations II The Royal Cemetery Plates. Oxford: The University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zevit, Ziony. 2001. The Religions of Ancient Israel. A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches. London and New York: Continuuum. [Google Scholar]

- Ziffer, Irit. 1990. At That Time the Canaanites Were in the Land. Daily Life in Canaan in the Middle Bronze Age 2, 2000–1550 BCE. Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Ziffer, Irit, and Dina Shalem. 2015. “Receive my breast and suck from it, that you may live.” Towards the imagery of two ossuaries from the Chalcolithic Peqiʽin Cave. UF 46: 456–88. [Google Scholar]

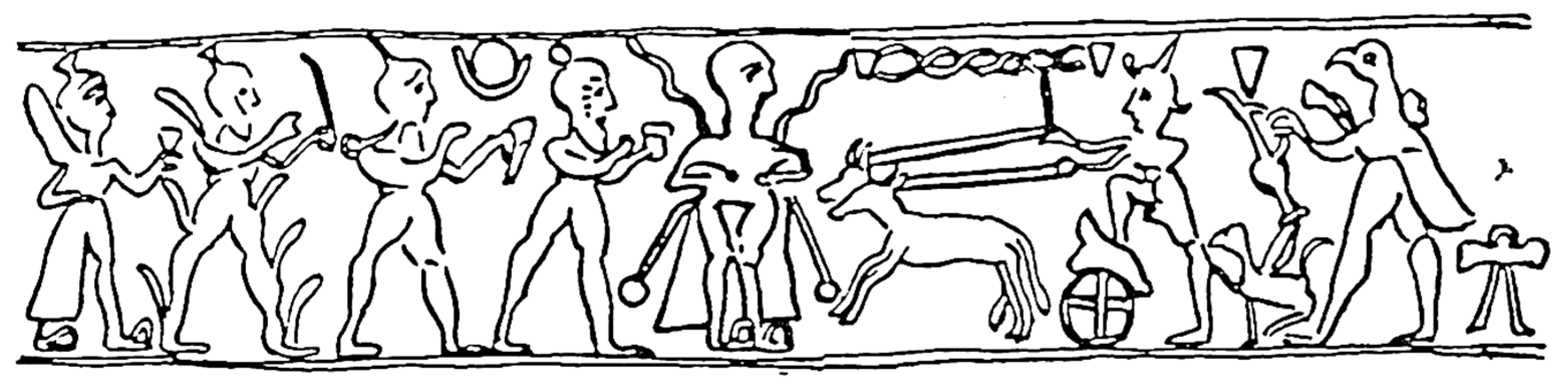

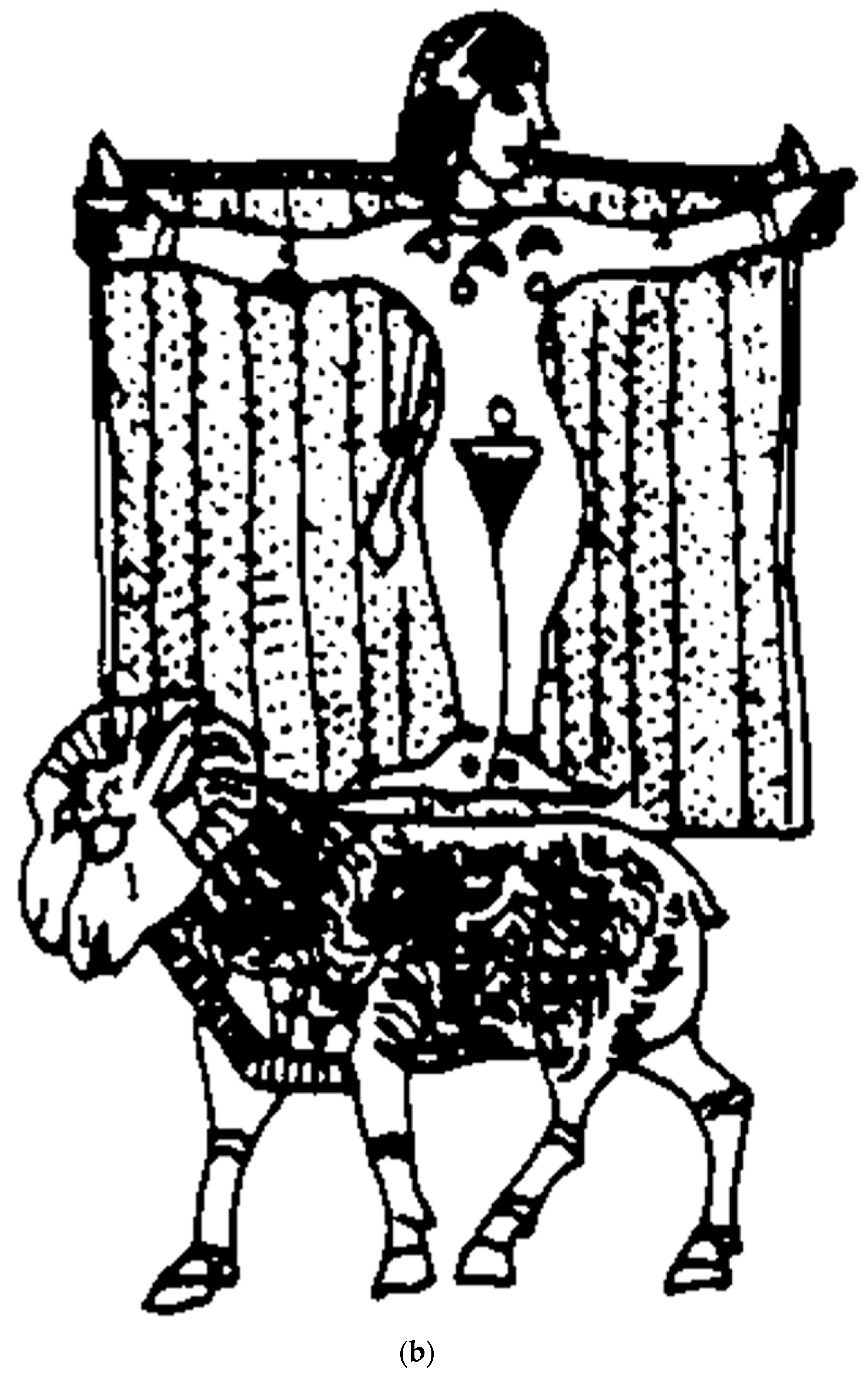

| 1 | (Garfinkel 2018), who regards the scene as the earliest representation of weaving with a loom. |

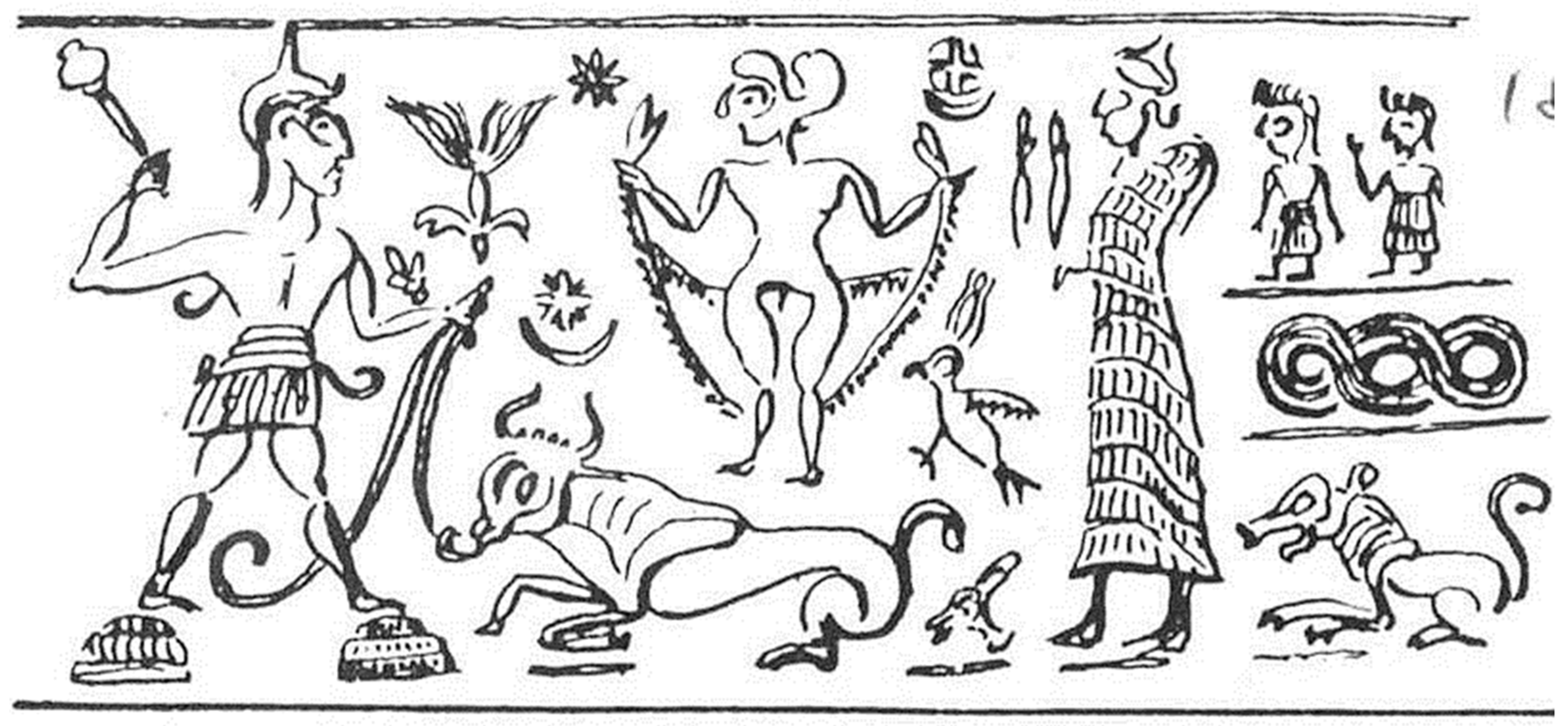

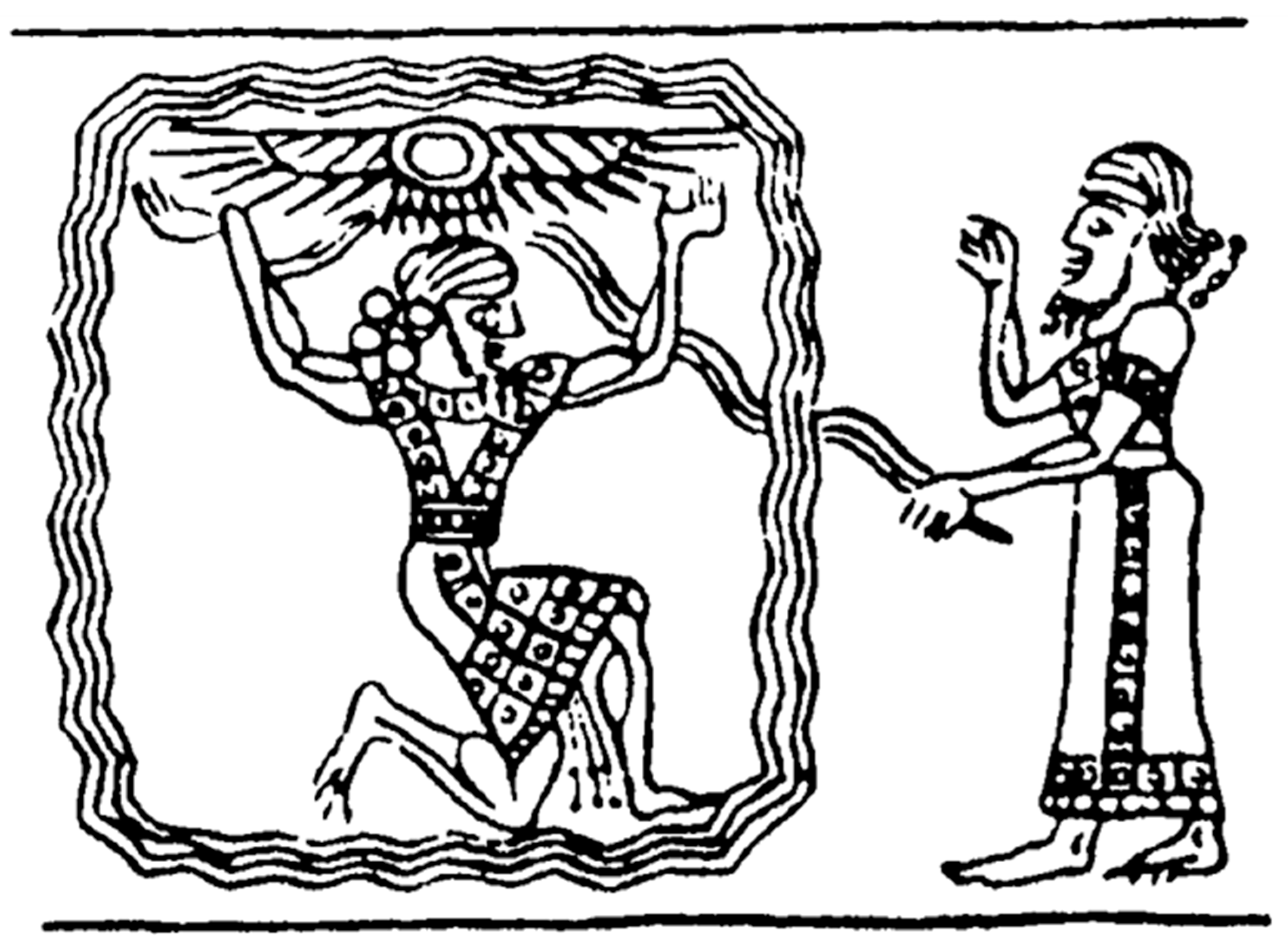

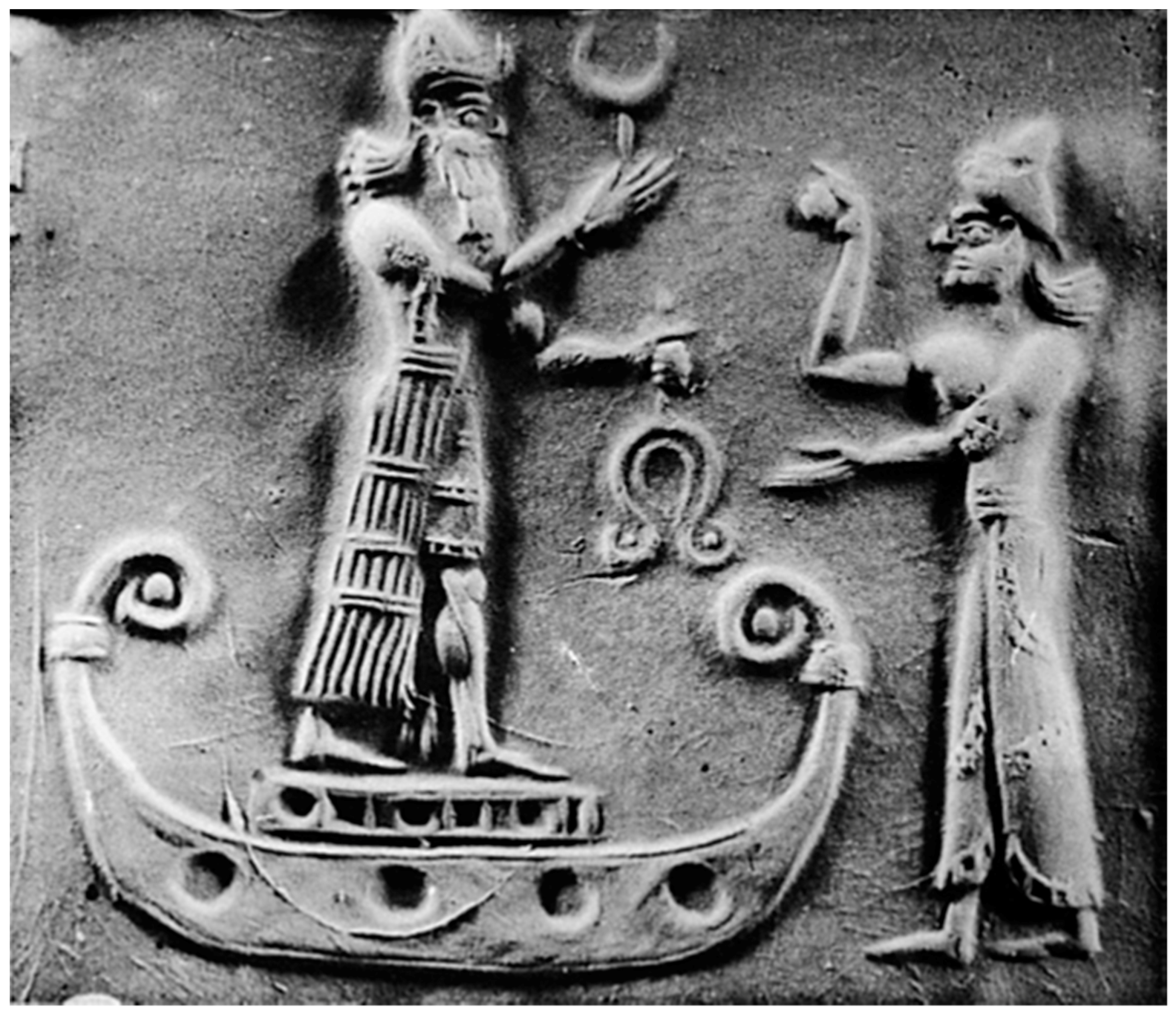

| 2 | (Black and Green 1992, pp. 110–11), Figure 89. Boehmer tends to interpret the whip as thunder, to van Loon the cracking of the whip signifies lightning, (van Loon 1990, p. 365). |

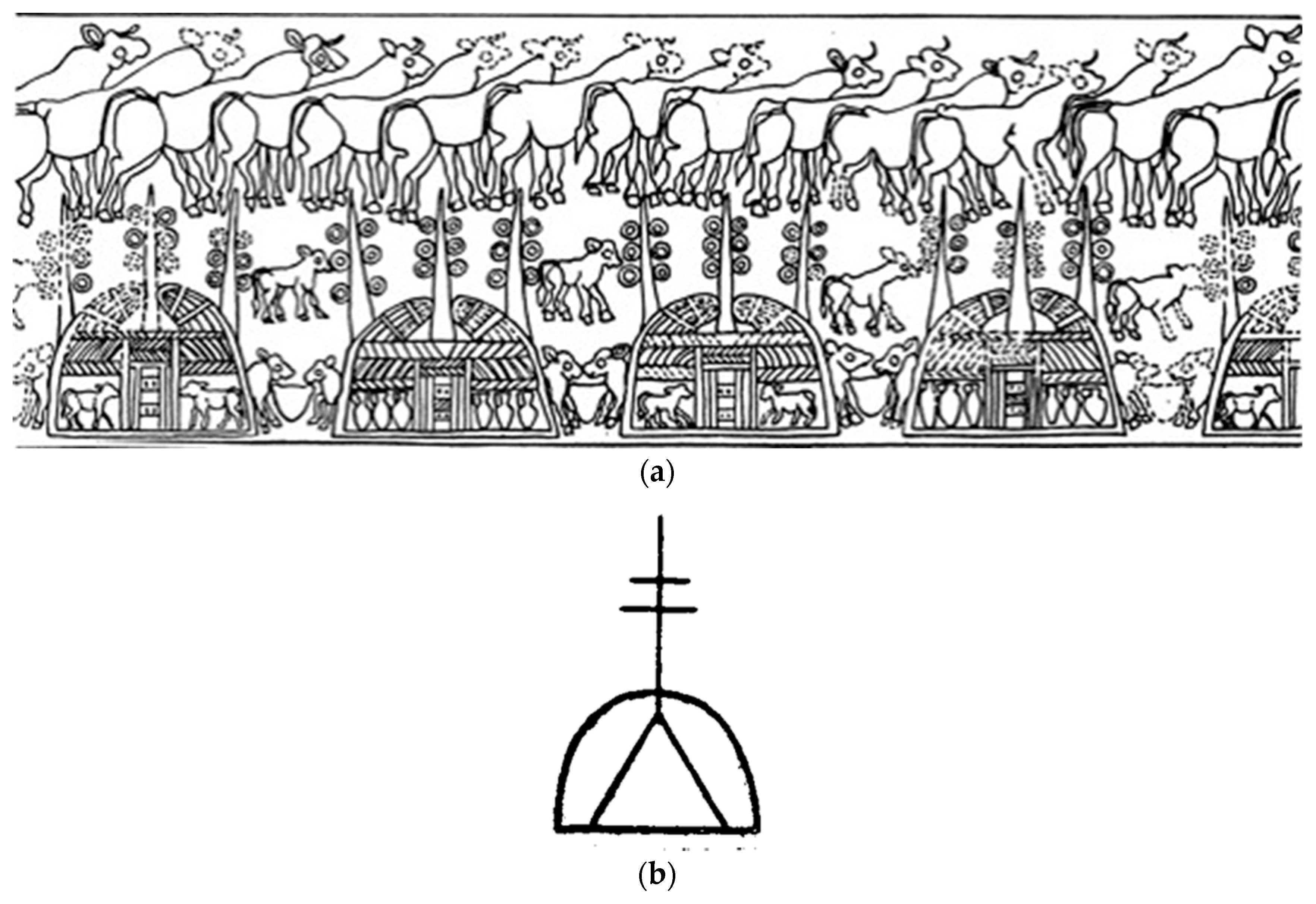

| 3 | |

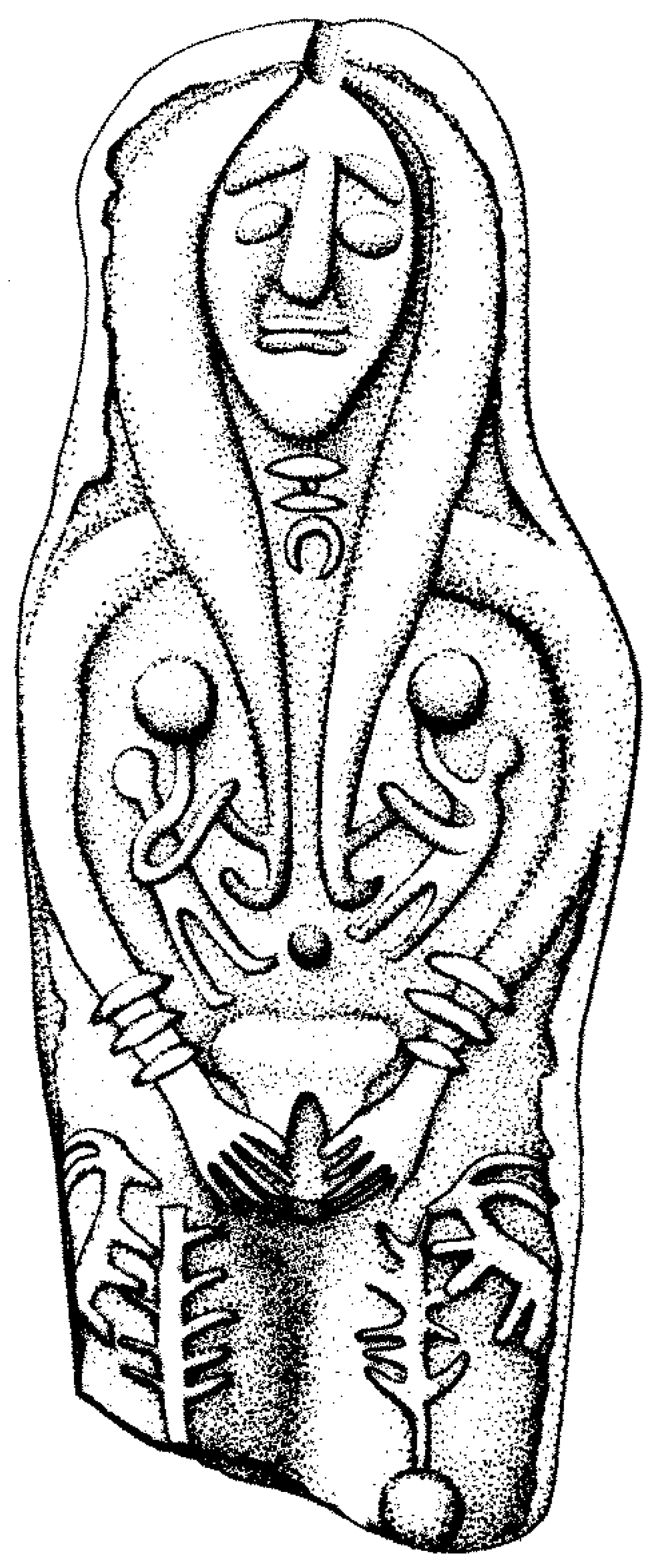

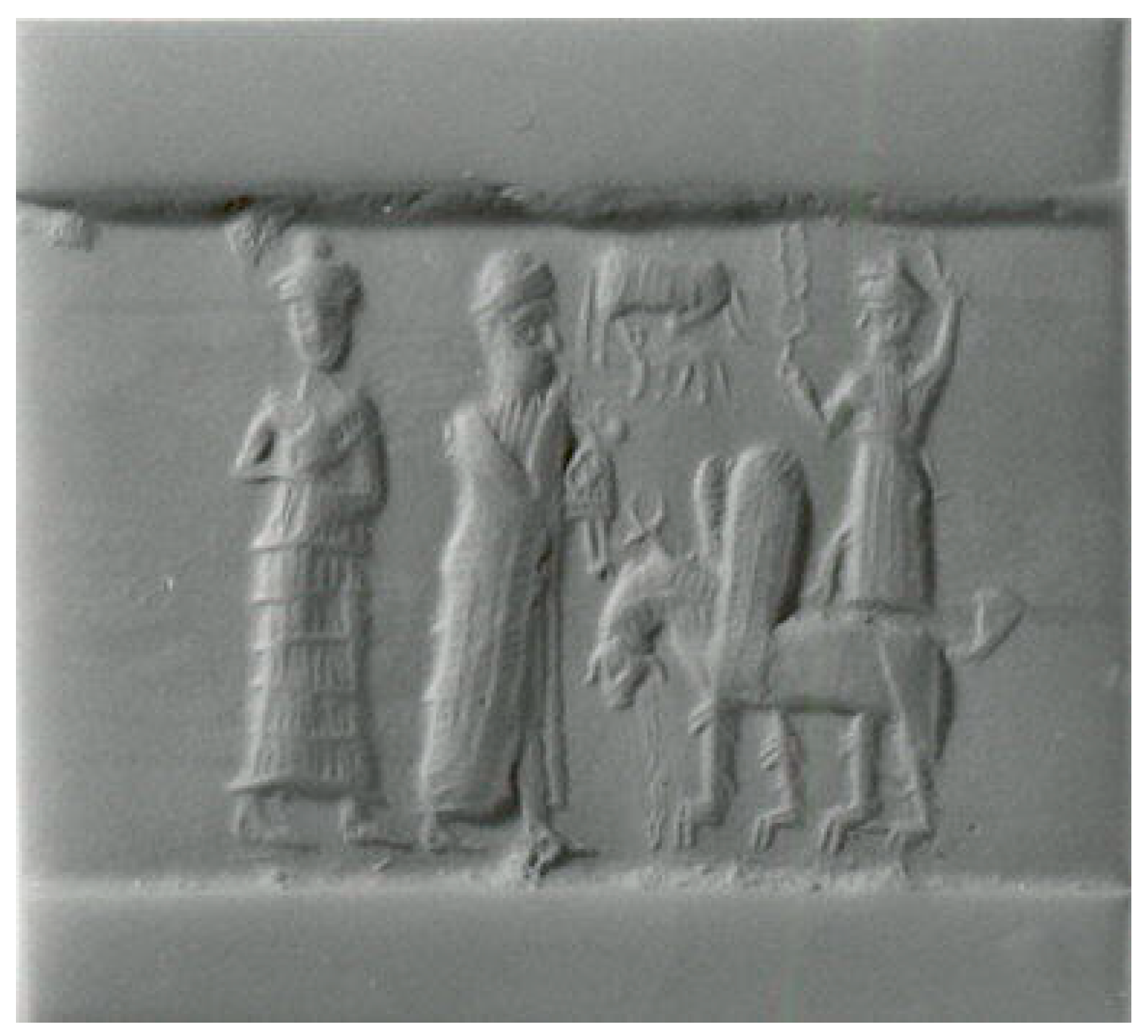

| 4 | |

| 5 | Compare the Urnamma stele upper register of both faces, showing flying goddesses pouring undulating streams of water from vases above the seated king, which Jacobsen construed as mythopoetic representations of the rain clouds ((Jacobsen 1987), p. 393 note 24; (Suter 2000): Figure 33a–f for the various reconstructions of the stele). The same goddess dives down on Gudea’s stele top in Berlin ST. 1–2 (Suter 2000): Figures 17, 19d, pl. B. |

| 6 | Undulated lines, possibly rain, appear behind a god on a bull on a Mitannian seal impression from (Beyer 2001, p. 227, no. E41). |

| 7 | For the moon god’s chariot functioning as a celestial visible effect, the halo, see (Rochberg 1996, pp. 479–82). |

| 8 | Compare Genesis 1: 15–17. |

| 9 | Compare Deuteronomy 28: 12; Jeremiah 10: 12–13, 51: 15–16; Psalms 135: 6–7. |

| 10 | Halos surrounding the sun and the moon can be an indication of rainstorms (Rochberg 2016, pp. 142, 187). |

| 11 | In the Sumerian tradition Nanna was the father of Inanna and Utu (Black and Green 1992, p. 182). |

| 12 | Compare the West Semitic root ירח used to designate “month” and “moon” (Rendsburg 2009, p. 170). |

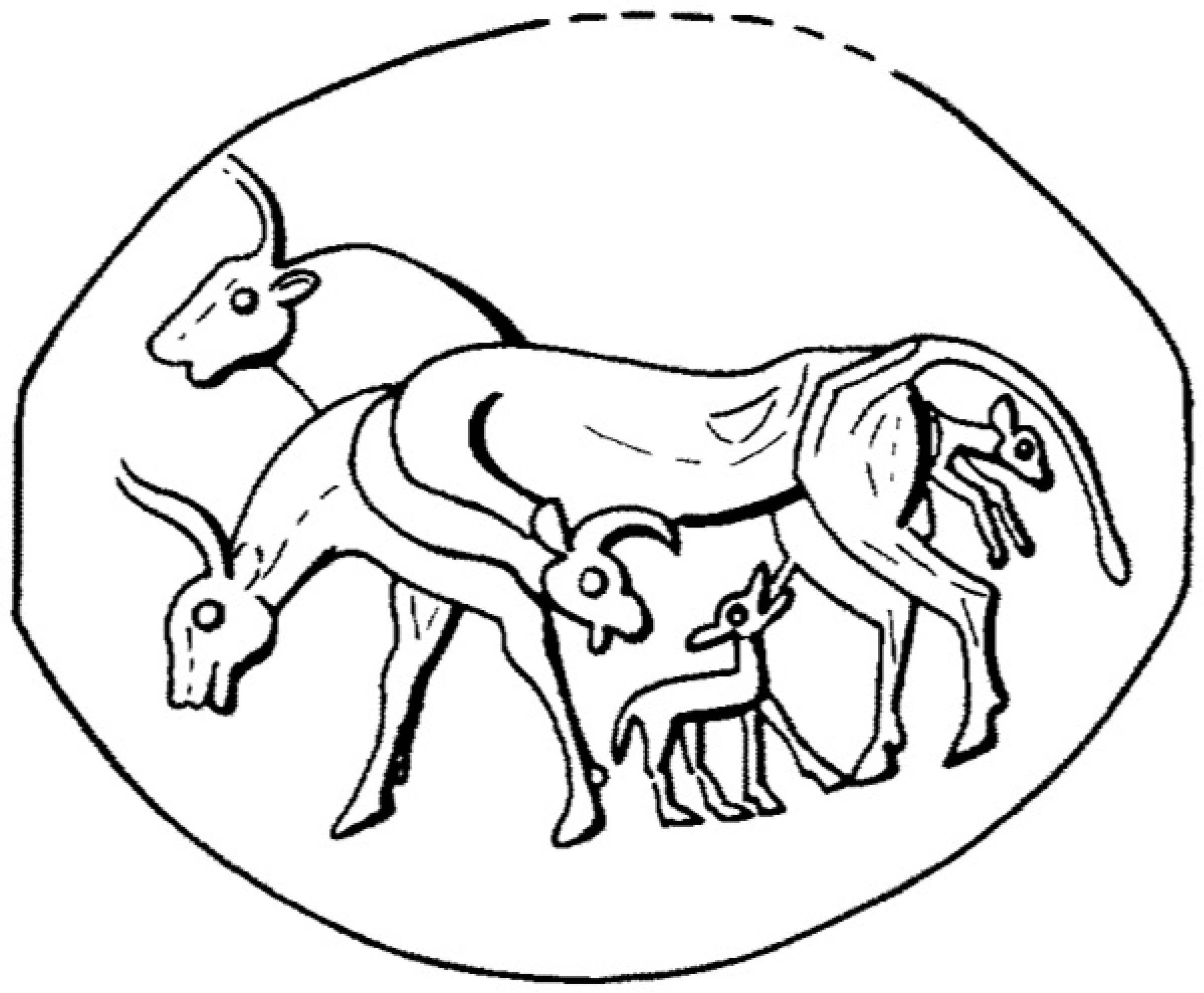

| 13 | At Emar, the god Šaggar had a significant role in promoting the welfare of the herds (Fleming 2000, pp. 156–57). It has been connected with Hebrew šeger (שֶׁגֶר) in the Aramean Ballam text from Deir ‛Alla (שגר ועשתר). In the Bible, שגר refers to the firstling of cattle drop and sheep flocks (שגר אלפיך ועשתרות צאנך), and parallels the issue of the human womb (רחם) (Exodus 13: 12) and (פרי בטן) (Deuteronomy 7:13, 28:4, 8,51). There may be a connection between the name Šaggar and the Sumerian logogram U4. SAKAR, Akkadian uskaru “lunar crescent” or Sin. Thus, it may refer to the moon metaphorically as a young bull. The same moon god appears at Ebla in the third millennium in a literary text as dSa-nu-ga-ru corresponding to I ITI “one month”/new moon" in a parallel text and is preceded by 2 SI, perhaps “two horns”, which reinforces the metaphor of the new moon as a young bull (Dalley and Teissier 1992, pp. 90–91). |

| 14 | In Mesopotamian love lyrics, inbu had sexual overtones “fruit, flower, sexual appeal” (Krebernik 1995, pp. 361, 366). |

| 15 | For New Kingdom feeding bottles in the shape of a woman wearing a crescent pendant, nursing a baby, or pressing her breast to collect the milk in a vessel, see (Brunner-Traut 1970: Figures 5 and 10). For crescent pendants worn by male figures in the Bronze and Iron Ages Near East, see (Ilan 2016). Iconography as well as archaeological finds confirm the use of crescent pendants by women, children and animals (as charms to promote harmonious growth) since ancient Egypt. In Greece, they go back to the Mycenaean period (Dasen 2003, p. 280); when buried with the dead, crescent pendants carried the hope of re-birth (Ziffer 1990, pp. 82*, 116). |

| 16 | Stol (1992, p. 249) concludes that the moon as bowl, boat and fruit represent the moon in all stages of growth, particularly the last one, which is the brightest. |

| 17 | (Sharvit 1972) on the oriental version (Genizah, Cochin and Singili, India) of “Eḥad mi yodea” song in the Passover Haggadah, employing the Aramaic term for the nine months of pregnancy. |

| 18 | Compare סהר “an enclosed place, especially the enclosure for cattle near a dwelling” (Jastrow 1903, p. 960). |

| 19 | The configuration of the crescent with the omega symbol has its antecedents in the art of the Middle Bronze Age in Babylonia and Syria (Keel 1989): Figures 34–36. Ulrike Steinert concludes that the omega symbol could stand for the womb and birth, a sign for divine mercy and good fortune, as well as an apotropaic sign (Steinert 2017, pp. 206–23). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ziffer, I. Moon, Rain, Womb, Mercy The Imagery of The Shrine Model from Tell el-Far‛ah North—Biblical Tirzah For Othmar Keel. Religions 2019, 10, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10020136

Ziffer I. Moon, Rain, Womb, Mercy The Imagery of The Shrine Model from Tell el-Far‛ah North—Biblical Tirzah For Othmar Keel. Religions. 2019; 10(2):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10020136

Chicago/Turabian StyleZiffer, Irit. 2019. "Moon, Rain, Womb, Mercy The Imagery of The Shrine Model from Tell el-Far‛ah North—Biblical Tirzah For Othmar Keel" Religions 10, no. 2: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10020136

APA StyleZiffer, I. (2019). Moon, Rain, Womb, Mercy The Imagery of The Shrine Model from Tell el-Far‛ah North—Biblical Tirzah For Othmar Keel. Religions, 10(2), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10020136