1. Introduction

Since the end of the last century, religious sites across Europe have seen an unprecedented influx of secular visitors constituting religious sites as ‘contested’ places, where there are conflicts of interest over access and usage (see

Digance 2003, p. 114). The revitalized interest in ecclesiastical heritage and spirituality falls within the margins of the ‘post-secular’ era (

Vattimo 2005, p. 45), in which non-faith-based groups acknowledge the social and cultural role of religious heritage. Therefore, religious sites have had placed upon them multiple identities suggestive of their new ‘profane’ (for some scholars, religious tourism sparks a celebration of consumption and a sense of hedonism; see (

Knox 2014)) and ‘sacred’ profile. In this regard, Cohen coined the term ‘educational pilgrimage’ to denote a growing phenomenon in which visitors seek knowledge and spirituality which cannot be found at home, either as cultural education for the ‘exotic other’ or ‘for one’s own religious roots’ (

Cohen 2006, p. 80). Thus, the notion of secular needs at religious sites, which was seen initially as ‘unbecoming and obtrusive’, has been replaced by an extrovert policy approaching religious sites as places of cultural and educational regeneration (

Kurmanaliyeva et al. 2014;

Curtis 2016). In this context, interpretation has taken on an important role in communicating the meanings of the place, building connections between visitors’ prior knowledge and the new information being presented (

Hughes et al. 2013). This article considers the field of religious tourism education as the main subject of its study.

Through the pervasive reality of secularisation, Christian churches have undergone a cultural transformation. In this way, spiritual/religious value is venerated alongside the historical, communal and aesthetic endowment. This new cultural reality, which would have been anathema (and probably still is) to earlier generations of clergy, raises difficulties in forming holistic interpretations to a heterogenous group of visitors, who often are at variant with institutional faith. Secular and religious management practices are encompassed under two distinct ontological standpoints. The first is expressed through the notion of ‘heritagization’, the process in which a pre-existing site with alternative uses and values, acquire new functions and is venerated for different values. The second defends churches as places of worship, against aestheticization, in which ‘tourists regard much of what they encounter in terms of the beautiful, the uplifting, the edifying’ (

Stausberg 2011, p. 12) and museumification, the preservation of the site to a particular timeframe (

Di Giovine and Garcia-Fuentes 2016, p. 13). Thus, European ecclesiastical heritage is shaped by morphogenetic (adaptability, development, change) and morphostatic (preservation and introversion) strategies (see (

Archer 1995) on social morphogenesis).

As Di Giovine and Garcia-Fuentes have argued, the ‘heritagization’ process has its roots in museological practice, which entails a process of recontextualizing a site from its original use to a historic object, subject to objectification and bureaucratization (

Di Giovine and Garcia-Fuentes 2016, p. 11). The hybrid (sacred and secular) identity of religious sites today raises various tensions between stakeholders over the management of religious sites (see

Shackley 2002,

2005). Religious sites are contested over access and usage between visitors and host communities that unbalance the ‘religious ecosystems’ challenging the symbolism of the place (

Shackley 2002;

Digance 2003;

Collins-Kreiner and Gatrell 2006;

Rivera et al 2009;

Kurmanaliyeva et al. 2014). The multiplicity of voices exerting control over the meanings of churches and their cosmological understandings is the focus of this article (see

Di Giovine and Garcia-Fuentes 2016). Throughout the article, the terms ontology and ontological perspectivism have been employed to help elaborate on this issue. Ontology is concerned with the nature of social realities (see

Bryman 2012). In this article, it is utilized to contextualize two distinct viewpoints over the nature of religious heritage. The first is expressed through an eternal and fixed reality (the religious viewpoint), and the second, a nature which is subject to new social and cultural frames of reference (the secular stakeholder viewpoint). Ontological perspectivism, on the other hand, is where ontology is manifested and demonstrated through practices, strategies and policies that comprise stakeholders’ vision. The notion of a hybrid religious space aiming to meet the expectations of a grown multilayer pilgrimage has attracted more attention in the field of anthropology (see

Turner and Turner 1978) rather than museum studies. This article examines the extent to which ontological plurality influences heritage practices at religious settings and in particular the way ecclesiastical heritage is negotiated and presented to visitors.

2. Faith: The Intangible Aspect of Religious Heritage

For some anthropologists, religious tourism has replaced faith-based pilgrimage. As Stausberg indicated, social theory has already acknowledged the structural replacement of the pre-modern/pre-industrial religious structure with tourism (

Stausberg 2011, p. 19). The investigation of the ‘the multi-layered meaning of pilgrimage’ has become a key instrument in understanding the multiplicity of motivations, attitudes and behaviours in religious tourism (

Graham and Murray 1997, p. 401). The debate over the nature of pilgrimage is summarized under convergence and divergence approaches (see

Cohen 1992). The first, de-differentiates the two actors, understanding tourists as a ‘modern pilgrim group’ travelling to fulfil their psychological needs (see

Knox 2014;

Collins-Kreiner 2010;

Damari and Mansfeld 2016). On the contrary, the divergent theories approach the tourist experience as ‘inauthentic’, interested in tangible evidence and events, arguing that tourism lacks the fundamental motivation of pilgrimage experience, the intrinsic emotional connection with the holy place (

Orekat 2016;

Eade 1992;

Fleischer 2000;

Singh 2009). Within the margins of modern religious tourism, a more complex search for multi-faceted spirituality (

Curtis 2016, p. 18) has emerged, coupled with an ‘aesthetic obsession with authenticity’ (

Bremer 2006, p. 32). In this context, the current article shifts the interest towards the concept of ‘religious tourism education’, examining the strategies underpinning the presentation of the tangible and intangible aspects of religious heritage.

Cultural heritage encompasses a tangible and an intangible dimension. Regarding ecclesiastical heritage, if the tangible aspect is represented through the stained glass, the frescos and the wooden reredos, then faith, religious practices theology, ritual, creeds, shared worldviews and mythologies occupies the intangible dimension. According to the Quebecois declaration of ICOMOS regarding the preservation of the spirit of the place, the intangible dimension of the past ‘gives meaning, value, emotion and mystery to a place’ and with the tangible aspect, they mutually constitute the spirit of the place (

ICOMOS 2008, p. 2). The last is composed of multiple meanings; it is subject to change and it belongs to multiple groups (

ICOMOS 2008). As will be shown later, the secularization of the current interpretations which are encountered at religious sites, place a disproportionate emphasis on the secular cultural values of the religious assets. Thus, the selective presentation of religious heritage to visitors runs the risk to trivialize and compromise, ‘the very object of portrayal’ (see

Dann and Seaton 2001, p. 20). This raises concerns on what place the Christian faith occupies in the cultural maps of contemporary European societies.

3. The Scope of the Research/Methodology

The need for this article was conceived after a number of research trips to European churches in the context of the author’s PhD research. During these trips, the author was intrigued about the frequency and the context in which religious connotations are contextualized and presented in churches. A meaningful interpretation aims to reveal meanings and relationships, rather than simply communicate factual information (see

Tilden 1957). Although few scholars have acknowledged the ‘secularization’ of interpretation at religious sites (such as

Voase 2007), this research aims to investigate the source of this phenomenon. In this line of thought, this article investigates why certain interpretational strategies are preferred over others at Christian churches. Thus, this article shifts its interest towards museological practices, investigating why postmodern interpretative strategies that advocating for critical engagement and polysemy have not earned ground in religious settings. In this regard, the article examines the converging and diverging points between the cultural paradigms advocated by ‘New museology’ and some Christian denominations. This comparative analysis aims to investigate the applicability of the dominant postmodern cultural paradigm to provide interpretative strategies which tell stories about faith in religious contexts. This article draws upon the author’s fieldwork at ten Anglican Churches, two Catholic Churches and a cluster of ten Orthodox churches between 2017 and 2019. For this study, it was of interest to investigate a number of primary sources, such as guidebooks available at the churches, supplemented by audio guides, in situ labels, panels and interactive displays (where available). The selected literature represents the official interpretation and it was chosen due to its authorization by the church in an attempt to determine the agenda and the sensitivities of the last.

The interpretations were examined following a thematic analysis aiming to elucidate broader assumptions and underlying ideas underpinning the interpretive strategies articulated in religious tourism literature. ‘Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data in relation to the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set’ (

Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 6). The research followed a deductive approach. This approach was selected to help answer the question of how popular the postmodern cultural paradigm is in religious tourism education. Thus, the research was interested in finding what strategies are recruited to initiate religious references in the tourist literature and how polysemic and provocative interpretations, welcoming critical and active engagement, played out across the data. The research was unfolded in four stages.

In phase one, various data of analysis were coded, such as ‘Jacob saw a ladder between heaven and earth, with angels ascending and descending’, ‘in the windows the biblical ‘types of the sacrament of baptism can be seen’, ‘…in the crowning pediment, God the Father giving his blessing’, ‘to be a pilgrim was to have a dual citizenship’. During phase two, several codes were produced in an attempt to organise the data in a meaningful way. The codes are related to the research question, indicating how religious references are introduced to the reader through the text, such as ‘identification’, ‘illustrative’ ‘inclusive’, ‘analytical’, ‘multiple interpretations-polysemy’, ‘critical active engagement/challenging/provocative’, ‘relative’, ‘absolute’, ‘factual’, ‘consensus’ and ‘absence of religious references’. During the third stage of analysis, the codes were combined together, producing the following three recurrent themes: Theme 1—‘Deficiency of religious references’ refers to the interpretations preferring historical facts, devoid of intangible spiritual aspects, providing some identification for the holy scenes (such as the topic of the theme or who is presented in it). Theme 2—‘Modernist interpretational strategy’ refers to the presentation of religious information in a linear transmission model, in which a strong curatorial voice aims to inform instead of challenge. This paradigm has an illustrative character aiming to elaborate on certain scenes utilizing facts or biblical references. Theme 3—‘Postmodern interpretational strategy’ refers to interpretation which utilizes religious references in an engaging why to spark further interest and provoke the reader to consider religion in its broader spiritual, social and cultural context. These three themes were not the only prevalent themes across the data, but they also represent an important element of the way religious connotations are distributed in the tourist literature at religious sites. During the fourth stage, the research follows a latent analysis, aiming to investigate what conditions, give rise to each theme and what norms guide interpretational practices at religious sites. Thus, through an interdisciplinary approach, the research aims to examine ‘the underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualisations–and ideologies-that are theorised as shaping or informing the semantic content of the data’ (

Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 13).

4. Balancing Materiality and Spirituality

The postmodern cultural paradigm aims to generate ‘holistic’ interpretations to spark visitors’ cognitive and emotive aspects. This chapter discusses how these strategies have been expressed in religious settings. The educational programs encountered in the Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches vary in terms of their holistic approaches, depth of meaning and visitors’ engagement. A closer look into the interpretations presented by Anglican churches in the United Kingdom, Catholic churches in Spain and the United Kingdom, as well as Cypriot Byzantine Orthodox churches, reveal variations in the way these three denominations espouse their museological strategies.

According to Historic England, spiritual value ‘reflects past or present-day perceptions of the spirit of place and it includes the sense of inspiration and wonder that can arise from personal contact’ (

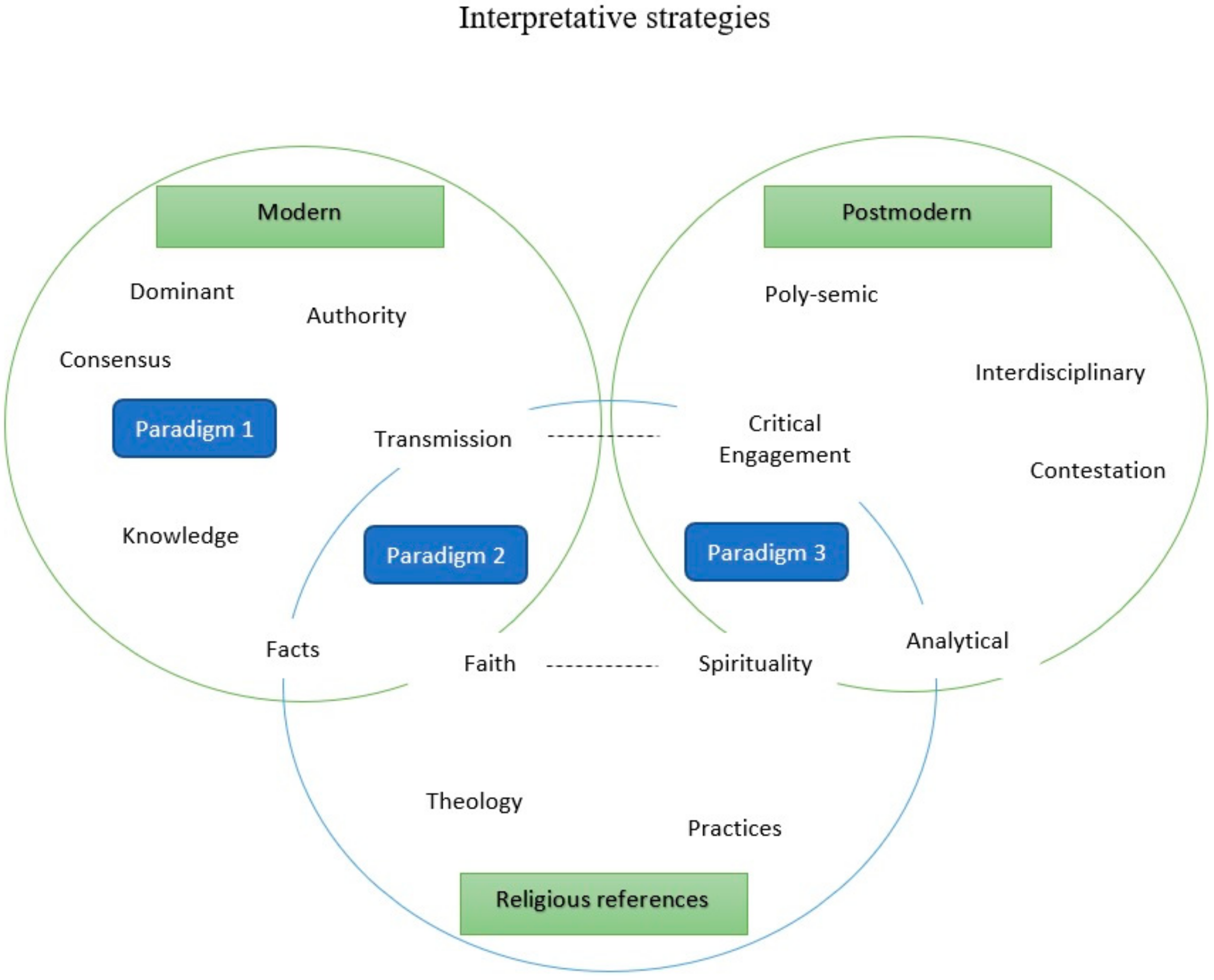

Historic England 2008, p. 32). Although this description mirrors the essence of New Museology in creating personalised interpretations, the same cannot be said for its application. The thematic analysis of the interpretations revealed three themes reflecting, to a large extent, overlapping interpretational paradigms. The first two paradigms follow the ‘modernist version’ of interpretation characterised by linear narratives of a dominant curatorial voice aimed at transmitting information and achieving consensus. The third paradigm executes tentative steps in adapting the ‘postmodern version’ of interpretation (see

Figure 1). While the first rejects theological connotations, putting religious material culture under the veil of a secular metanarrative, the second and the third paradigms utilise religious connotations in a manner proportionate to the preferred, modern or postmodern interpretive strategy, respectively. The presentation of religious connotations does not necessarily suggest a transition from the modern interpretative framework to the postmodern. As will be explained, the transition from the second to the third paradigm requires an ontological shift (from modern to postmodern), in which the meanings of the place are negotiated under a new cultural ideology reflecting the current plural and relative sociocultural frame of reference. The following analysis demonstrates how different churches utilize the aforementioned paradigms to narrate their stories. It should be treated as a case study aiming to explore the ambiguous relationship between secular education and religious space and to establish causal relationships (see

Gray 2009), and it should not be generalised to all types of denominations everywhere.

5. First Paradigm-Deficiency of Religious References

The modern interpretative strategy tends to prevail in religious tourism education and seems to be the prominent model of interpretation across Christian Churches. In this model, religious information (scriptural, theological, liturgical, etc.) is almost entirely absent from the educational programs. On the one hand, the fear of indoctrinating non-religious visitors prevents the elaboration on the theological semiology and deeper meaning. On the other, it runs the risk of secularising the place, as ‘true believers’ do not like their faith to be challenged (

Olsen 2003). This model calls for linear narratives prioritising historical facts over a holistic analysis of religious material culture. The dominant curatorial voice substitutes polysemy (the capacity of having multiple meanings) and critical engagement in favour of linear (didactic) transmission fostering a consensus of ideas. In this paradigm, religious references are either absent or are expressed as a reference of identification for the presented figures. Characteristic examples include the painted Byzantine churches in Cyprus, which place emphasis on the typological classification of Byzantine architecture, such as the unique rural style of steep-pitched wooden roofs (

UNESCO n.d.). Although this characteristic is unique, the interpretation fails to provoke the visitor by elaborating on issues such as the mingling of the practical, environmental, and spiritual reasons behind the architecture, or even current and future preservation strategies. Furthermore, the interpretations neglect to reveal the mystical otherness or grasp the deeper symbolism of religious art. For example, the interpretation omits to elaborate on issues regarding the coexistence of Orthodox and Latin churches. A historical paradox is that Orthodoxy adapted Latin iconographic elements despite the efforts of the Latin church to impose dogmatic beliefs and liturgical practices on the island (

Chotzakoglou 2018, p. 205). Consequently, the visitor may fail to comprehend the historical tensions as well as the ontological nature of Byzantine art which presents the world as an enigma with symbolically and metaphorically connected scenes (

Kazhdan 1991). This strategy raises concerns over the capacity of the linear modern narrative to provoke both the cognitive and affective aspects of religious tourism (

Thouki 2018, p. 2095). However, we should note that there is no clear-cut distinction between the paradigms, rather, there are tendencies. Although, the general norm in Orthodoxy is to avoid any religious references, as the in-situ interpretations indicate, the guidebooks present some religious connotations in an explanatory and illustrative manner, as exemplified in the second interpretive paradigm:

‘At about the same time the complex was transformed into a monastery with the construction of two wings of monks’ cells, on either site of the courtyard…most of the murals in the main church date to the 13th century and are dominated by the Pantocrator (all powerful God) fresco in the cavity of the dome. In addition to the four evangelists, the twelve apostles and several prophets and scenes from Scriptures…’

(Monastery of Agios Ioannis Lambadistis Cyprus, in situ panel)

‘The painter who worked at Podithou was strongly influenced by Renaissance art as many painters of that period, whose work is collectively known as the Italo-Byzantine style. Its main characteristics are the choice of vivid colours and the three-dimensional treatment of the subjects.

(Church of Panagia of Podithou Cyprus, in situ panel)

Cleary of a Eucharistic character, it is painted in the area next to the prothesis, where the bloodless Holy Eucharist, is prepared at every Christian Orthodox Liturgy [p. 45]… Joseph is shown seated on rocks… according to tradition, the devil taunted Joseph as to how it was possible for Mary, a virgin, to have given birth [p. 53]… there is an association between St Kyriaki and Sunday (Greek: Kyriaki), which is sanctified for Christians as the day on which Christ was resurrected and through His resurrection came the salvation of the human race [p. 86].

The censoring of theology from religious tourism education is not an endemic phenomenon. As Richard Voase argued, the secular-natured interpretations encountered in Anglican churches (endorsing the aesthetic value of the place) may restrict visitors’ ability to engage emotionally with the spirit of the place, undermining the sense of human connectedness (

Voase 2007). Many churches in the United Kingdom treat the theological background of religious heritage as a redundant attribute. The interpretations encountered in the majority of Anglican churches in England and Wales reveal that the marriage of postmodern strategies with religion is a daunting task even in places where Christianity is declining.

Lichfield Cathedral is a characteristic example of where the interpretation neglects to reveal the deeper meanings of religious art, such as the case of the enigmatic carving of Green Man, a pagan ornamentation which has been incorporated into Christian iconography. Lichfield Cathedral dates to the 13th century and it is well-known among archaeologists for its three 200-foot spires and the elaborate stonework including 113 statues (

Lichfield Guidebook 2014;

Crook and Brown 2002, p. 72). Among the rich carvings, the figure of Green Man was chosen to decorate some of the capitals of the columns. Green man is an anthropomorphic figure surrounded or made by vegetation (foliage). This decorative motif dates back to classical pagan antiquity, showing a close interreference between man and nature. Some believe that Dionysus, as the patron of nature and vegetation, is its archetypical form (see the ‘Enigma of Green Man’). Nevertheless, the motif of a Green Man has often been integrated into the western Christian iconography. This is significant to the history of early Christian art as it shows one facet of the transition from the pagan to the Christian world. However, when a contemporary heritage tourist enters the Cathedral, the tourist literature does not discuss the cross-cultural meaning of this pagan ornamentation, and (or) how old pagan beliefs were adapted and reconsolidated with Christianity. Is it a symbol of fertility, death and rebirth, life and nature or evil, associating Green Man as a demon (

Mastin 2011)? The purpose of interpretation is to ‘inspire and provoke people to broaden their horizon’ (

Beck and Cable 2002, p 39). Therefore, the absence of a provocative dialogue between interpretation and the reader downplays visitors’ critical engagement and self-knowledge. According to hermeneutic theorists, self-knowledge is the outcome of a constructive dialogue in which the learner should be given the opportunity to understand and interpret the otherness (

Rux 2007;

Aldridge 2011,

2018;

Wright 1997,

1998).

Similarly, Llandaff Cathedral in Cardiff avoids explaining why ‘The Fall of Man’ and the ‘Annunciation of the Virgin Mary’ have been chosen as the preferred imagery to decorate the font where an important point of the Christian journey, baptism (

Llandaff Guidebook 2014), takes place. In the same vein, the new interpretation of St. Cadoc’s Church in Llancarfan (South Wales) gives a descriptive account of the recently uncovered fresco of the ‘seven sins’, making no attempt to elaborate on the meaning of sin in the medieval period (

Thouki 2018, p. 2094). Additionally, a number of churches, such as St Mary’s parish church in Staindrop (Co. Durham) and St. Woolos Cathedral in Newport (Wales), neglect to elaborate on their architectural and pictorial art, such as the association of the rare moulted trefoil niches within the Holy Trinity and the spiritual advantage of someone buried (effigies, sarcophagus, tomb niches) in a consecrated ground (see Christian Burial in

Catholic Encyclopaedia n.d.) respectively.

A typical Green Man carving shows a face appearing from foliage, in the Chapter House carving, which is unusual some of this oy is also included, and a few meters away is a Green Woman. Other Green Men can be found in different parts of the Cathedral [p. 9].

The effigy set into the north wall of the Teilo Chapel is of Lady Audley, who died in 1409… the stained glass in the east window is by… and depicts Christ the Kind, with Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist on the right, and Elizabeth, with the boy John the Baptist on the left [p. 11].

The niche houses the mutilated remains of an alabaster monument to the memory of … a knight of the Holy Sepulchre, died in 1491 [p. 35] … The symbolism of these carvings speaks to modern commentators of either the story of Noah’s flood of the Baptism of Jesus, and so of Baptism generally [p. 36].

6. Second Paradigm-Modernist Interpretational Strategy

Nevertheless, the number of churches utilising religious information to enrich visitors’ educational programs is growing. Although in this paradigm, religious references are still scarce, they are mostly utilized as the ‘illustrative component’ of religious art. Some examples can be found in the York Minister guidebook, elaborating on the diachronic importance of ‘pilgrimage’ and its symbolic stonework and woodwork respectively, yet Catholic and Orthodox churches execute tentative steps in this direction. In particular, the Roman Catholic church of St James in London utilises biblical verses to explain the symbolic selection of prophets to accompany the Virgin Mary on wooden reredos. Similarly, both the audio tour and the guidebook of the Granada Cathedral in Spain inform the reader how various scenes are allocated within the fabric of the church. Additionally, they elaborate on the symbolism of the pictorial art such as the pomegranate held by the Virgin Mary, the symbol of Granada.

The colours of the Altar cloths, or frontals, here as elsewhere in the Minster, are changed according to the season in the Church’s year, they vary from richly embroidered white and gold for festivals such as Christmas and Easter to solemn blues and purples for the penitential seasons of Advent and Lent [p. 43]… St Nickolas is the patron saint of, among others, children, sailors and pawnbrokers. He is also ‘Santa Claus’, and for that reason the kneelers who the verses of the song ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’ [p. 54].

The cross indeed in God’s mystic answer to the perennial questions of pain, injustice loss and death, for there God Himself endured the worst that men could do to Him and offered His free, loving forgiveness [p. 7]…congregation can see and share in the ceremony [baptism], when a new soul is received into the congregation of Christ’s flock’ and singed with the cross as a ark of God’s loving acceptance [p. 9].

Above the black and gold grille… is the image of the hart, which refers to the words of Psalm 41–Like as the hart desireth the water brooks, so longeth my soul after thee, O God’ [p. 31]… wonderful reredos… this contains a series of Marian symbols–the vine, the rose and the lily…beneath this images of Old Testament characters who prefigured and prophesized the Virgin Mary… Daniel and the mountain (Daniel was able to interpret a dream of Nebuchadnezzar, in which a great statue was broken into pieces by a little shone, which grew into a mountain. This symbolized the Messiah born of a Virgin [p. 36].

Next the small oil painting of ‘Our lady of Forgiveness’ alluding -as the title itself indicates- to the subject of forgiveness, makes it possible for the protection of the pilgrim apostle in this defence of the faith to turn into victory as the centre of the attic, thanks to th central anonymous image of the Virgin Mary [p. 70].

Although religious information is presented in the interpretations, as the second paradigm indicates, these examples retain the ‘factual’ and ‘absolute’ conceptual framework of modern strategies. Conversely, the third paradigm reflects an attempt by religious sites to adapt the postmodern cultural paradigm by reaching out to new audiences. Postmodern strategies utilise theology not just as an ‘illustrative’ component of religious art but as an emotive and cognitive stimulant. On this account, the postmodern paradigm advocates for a shift from the inward-looking theme of faith to the inclusive concept of spirituality and forms the interpretational strategy of linear transmission towards critical engagement

7. Third Paradigm-Postmodern Interpretational Strategy

The advent of postmodern strategy in religious tourism education is evident in some Anglican churches, some of which are situated in the multicultural and multifaith environment of London. St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey welcome all visitors to be a part of a universal spirituality which transcends the narrower Christian values, reaching for polysemy and inclusiveness ‘aiming to serve all people, irrespective of their status or faith’ (

St Paul’s Cathedral Guidebook 2017, p. 3). This development signals a gradual transition from the concept of faith to the concept of spirituality (see

Figure 1). As Wade Clark Roof explains, the term faith has been broadened from its doctrinal base to refer ‘to the presence of the human spirit of soul, and the human quest for meaning and experiential wholeness’ (

Wade 2003, p. 138). In this manner, the postmodern religious space aims for a constructive learning environment favouring integrated (tangible and intangible) interpretive themes. The Westminster Abbey audio guide, for example, makes a specific reference to Charles Darwin, who is buried in the Abbey, although his influential theory on human evolution has deeply troubled religion. Additionally, the Abbey is presented as the ‘jewellery of the commonwealth’, a place where leaders of former colonies (such as Nelson Mandela) are commemorated (see also

Westminster Abbey Guidebook 2013). In this regard, London cathedrals become the ‘nation’s temples’ where British society embrace and recontextualise its past. Lastly, the interpretation provokes the visitor to imagine the space as a place of reflection and inspiration. This is in line with a general turn in many Protestant churches after the 1970s which was affected by a conservative evangelical revival in the margins of ‘charismatic spirituality’ emphasizing the experience of spiritual gifts, faith healing and new unstructured services instead of traditional forms (

Bray 2007). Likewise, the new interactive display of Worcester Cathedral speaks of pilgrimage as both sacred and secular. The interpretation argues for a ‘dual citizenship’ in which the individual lives according to God’s guidelines without comprising their adventurous spirit. Additionally, the interpretation stimulates all the senses, describing how the importance of light defines the interior of the Cathedral, something addressed in Durham Cathedral as well. In the same spirit, All Saints Parish Church in Backwell Derbyshire makes provocative statements on how the teaching of the church affects the society diachronically. In the following examples, we observe a transmission from a narrative of consensus to analytical interpretations which challenge, provoke and spark contestations.

A pilgrimage can be anything from an organized trip with a group to a spontaneous and private experience in response to a special place. It offers time and space to stand back and explore our own lives and thoughts, taking time out of the ‘ordinary’ to reflect upon our ‘journey’ through life, something many people find helpful and easier when they visit a place like this.

(Worchester Cathedral England, Interactive Display)

The medieval emphasis on the virtue of almsgiving or on acts of humility as penance implied a divine bias towards the poor and humble. A Bakewell parishioner in the Middle Ages, however impressed by rank or wealth, would have taken it for granted that, were Christ to come again on earth, he would be a beggar not a nobleman [p. 5].

The consecrated bread that Christians believe is the body of Jesus, shared at services of Holy Communion [p. 14]… the painting travelled the world… it was considered an important painting with a strong spiritual message – to be seen by many and achieved celebrity status. It claims a place of recognition for Judaism and Islam in the light that shines from Jesus Christ. The start of David and the Islamic crescent moon can be seen on the left side of the lamp that Jesus holds [p. 22].

(St. Paul Cathedral London, guidebook 2011)

It is evident in the aforementioned examples that the interpretations depart from the modernist style following a linear-didactic transmission of information to a postmodern interpretative strategy, favouring critical engagement and inclusivity. In particular, the interpretations spark visitors’ cognitive and emotive components by creating a constructive dialogue between the visitor and the exhibition. The interpretation addresses intriguing ideas aiming to ‘hook’ the reader into engaging with the universal notions of ‘spirituality’ and ‘self-realization’. Conclusively, the main distinction between the second paradigm and the third is the way they unfold their narratives. The difference comes down to interpretational methodology and in particular, how religious stories are presented to visitors. As R. Voase explains, narratives consist of two parts: the ‘story’ (content) and the ‘discourse’ (interpretational methodology). Discourse is the part of the narrative responsible for the way a story unfolds and develops (

Voase 2007). In this line of thought, stories found in religious heritage may include religious connotations, as paradigms 2 and 3 suggest. However, the way they unfold, following a modern (where the strong curatorial voice limits visitors’ critical engagement with the interpretation) or postmodern interpretational methodology, draws a dividing line between the two.

It is worth discussing these result in conjunction with the religious and secular cultural paradigms advocated by the three denominations and New Museology respectively. Thus, the following chapters aim to investigate the broader cultural framework in which heritage is assembled, negotiated and presented. By examining the converging and diverging points between the theoretical underpinning of New Museology and the ‘religious cultural paradigm’ (encompassing religious cosmological understanding), it aims to analyse why religious bodies appear to be more inclined to reject or embrace certain interpretative strategies.

8. New Museology

During the dawn of New Museology towards the end of 1990s, museums placed particular emphasis on public engagement and community involvement, creating engaged spaces to facilitate their funding and validity. As McCall and Gray states, New Museology introduced a new philosophy changing how museums engage with their societies and communities. Thus, the museum transitioned from a building-based institution, that was a collection-focused and upheld community truth as cultural authority so as to ‘civilize’ and ‘discipline’ its visitors, to an inclusive institution aiming to tackle discrimination, oriented towards a more visitor orientated ethos. Thus, terminologies such ‘cultural empowerment’, ‘social re-definition’, ‘dialogue’ and ‘emotion’ were introduced (

McCall and Gray 2014). In this context, particular emphasis was given to the educational role of museums, as well as natural and cultural heritage sites. These new practices were grounded in what has been loosely termed as ‘communication and educational theories’. These theories are aiming to replace the transmission modes of communication, from seeing audiences as passive receivers to a transactional model, in which visitors and curators engage in a mutually beneficial dialogue (

Mason 2006, p. 201,

Jeffery-Clay 1998). In this regard, the emphasis has been shifted to visitors and how they construct meaning based on their personal, cultural and political background (

Greenhill 1994). Among other influential theories, such as Piaget’s educational constructivism, New Museology has been influenced by the philosophical branch of hermeneutics. The work of Wilhelm Dilthey and Hans-Georg Gadamer, who advocated that meaning is always context dependent and holistic, has been recruited by ‘New museology’ to unlock visitors’ meaning-making mechanisms (

Greenhill 1994). In particular Gadamer and Martin Heidegger, achieved an ontological turn in hermeneutics by placing the emphasis on the importance of our past traditions and current sociocultural interaction in order to shape our interpretative horizon (

Ablett and Dyer 2009). Hence, prejudice/bias/pre-understandings become particularly significant in bridging what people already know with the given meanings of the site. In other words, the philosophical approach over hermeneutics has become the bedrock in forming relevant and holistic interpretations, bringing together visitors’ cognitive and emotive pre-occupations with the exhibited artefacts.

In our era, the reciprocal relationship between cultural heritage tourism and heritage is framed under the postmodern cultural paradigm. Postmodernism refers to a cultural paradigm with certain set of principles and standards arguing for a world which is irreducibly and irrevocably pluralistic (

Bauman 1992). According to Bauman, this world comprises an infinite number of narratives and meaning-generating individuals all autonomously geared with ‘their own facilities of truth validation’ (p. 35). This is marked by the ‘delegitimization’ of grand narratives and emphasis on communication, diversity and plurality, against grand narratives and the parochial acceptance of validity and objectivity (

Yuan 2019). This premise infiltrated heritage practices characterised by a great heterogeneity, aiming at criticizing and detotalizing the modernist conceptualization of truth and reality. The aim has been to form a polyvocal, inclusive, variable and tentative postmodern cultural space (

Heller 2006;

Hutcheon 1994). Along these lines, the difference between the modern and the postmodern cultural ideology lies in Bauman’s dichotomy between the interpreter, aiming for heterogeneity and cross-cultural enrichment of tradition, and legislator, someone who makes authoritative statements utilising a superior knowledge, the modern. This distinction signals a tradition between the modern and the postmodern ideological paradigms (see

Bauman 1992).

The aforementioned theoretical framework has been used in conjunction with Freeman Tilden’s notions of holistic, relevant and revelatory interpretation (

Ablett and Dyer 2009;

Tilden 1957). Tilden disengaged the notions of information and interpretation, explaining that ‘information, as such, is not interpretation, interpretation is revelation based upon information’ (

Tilden 1957). This combination formed a solid and influential framework of plural, polyvocal and inclusive strategies, aimed at stimulating the cognitive and emotive component of visitors, creating a symbolic dialogue between the interpretation and the reader (

Serrell 1996;

Uzzell and Ballantyne 1998;

Bitgood 2000;

Beck and Cable 2002). (

McCall and Gray 2014) concluded that although New Museology and the discussion associated with it has been useful tool for practitioners, the implementation of its ideology ‘has had less practical effect than the museology literature might anticipate’ (p. 31). The first comes down to the competing tensions between managers and curators within the margins of an ambiguous bureaucratized museum. The second is linked to the values and the personal assessment of museum staff to influence the implementation of museum policies (

McCall and Gray 2014). Similar observations and concerns are raised in this article indicating the decisive role of stakeholders and their personal values/ontologies, to apply the principles of New Museology in religious settings.

Although an increasing number of publications investigate visitors’ needs and expectations at religious sites in general, research neglects to investigate and incorporate stakeholders’ ontological perspectivism. In an attempt to unlock visitors’ meaning-making mechanisms, research has concentrated on various aspects, such as the influential role of religious affiliation in shaping visitors’ expectations and needs (

Božic et al. 2016). Moreover, most of the research was focused on visitations patterns and pilgrimage routes (

Fleischer 2000), the interplay of religious affiliation with behavioural patterns (

Öter and Çetinkaya 2016) demographics (

Irimias et al. 2016) as well as the feeling of national/cultural ownership (

Tucker and Carnegie 2014). Other studies concentrate on other influential mechanisms such as how visitors’ psychological profile and the feeling of immersion influence their perceptive mechanisms (

Francis et al. 2008;

Francis 2013;

Othman et al. 2013;

Nyaupane et al. 2015), while others examined identity-related motives (explorers, facilitators, professional, experience seekers, etc.) (see

Hughes et al. 2013). Although the aforementioned studies form a solid and informative body of literature regarding visitors’ pre-understandings, this article is concerned with the applicability of their recommendations. For instance, Hughes et al. advocated for ‘balanced interpretations that explain the religious as well as the secular aspects’ (p. 219), while Francis et al. argued for interpretation which will ‘spark the imagination and stimulate unanswered questions (

Francis et al. 2008, p. 14) and Bozic et al. argued for a new interpretations which will present the ‘historical and cultural values of the site for secular tourists, as well as presentation of the religious sense of the place’ (

Božic et al. 2016, p. 43). Such recommendations tend to overlook the decisive power that stakeholders have in how religious heritage is presented as well as the reluctancy of the Church to adopt more secular strategies of communication, such as the inclusive, poly-vocal and integrated (tangible and intangible) interpretational strategies advocated by the aforementioned studies.

9. From Pre-Modernity to Postmodernity, Adaptations and Rejections

Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Protestantism have divided the religious map of Europe since the 16th century, with each bearing particular historical, national and cultural roots within their regions. Since the Enlightenment, each denomination has developed its own adaptative mechanisms to defend its tradition over the intellectual developments of secular world. The question this article raises is whether the ‘ethics’ of the postmodern cultural paradigm advocated by ‘New Museology’ are considered suitable, by religious bodies, to present ecclesiastical heritage. Despite initial difficulties, Protestants and Catholics have come to terms with modernity. Although there are multiple interpretations among them (such as the Radical Orthodoxy movement criticizing the ‘site-lining of theology’ from the current secular culture, and arguing for the reintroduction of theology in public discourse (

Grumett 2011)), they have accepted and adapted their basic postulations of religious freedom, tolerance, and even liberal secular values as individual human rights within a plural society (

Makrides 2012, p. 250). Roman Catholics (especially after the Second Vatican council), even argued for a reconciliation between religion and the modern world (

MacCulloch 2009). Orthodoxy on the other hand, followed a different path characterized by inward-looking and persistence to ritual tradition, ‘cast by the west as oriental due to its unfamiliar ancient practices’ (

Kaldellis 2007, p. 3). For Orthodoxy, modernism undermines traditional values and the institutions underpinning them, expressing discontent over religious pluralism and whatever jeopardises fundamental Christian values (

Makrides 2012, p. 260).

The religious stance on postmodernity moves in the same way. Some scholars have suggested that postmodernism coupled with post-secularism, which advocates for tolerance and multivocality, could help religion to regain the spiritual ground that it has lost among believers. In this sense, ‘religious rationality’ is allowed to escape from the deterministic singular rationality of modernity and reclaim its spiritual place in a world turning its back to scientific, rationality and modern metanarratives (

Makrides 2012;

Freeman 2012). Although this premise holds ground among certain ‘postmodern theological schools’, arguing for a marriage of the two in a way that ‘Christianity would teach postmodernity about its own humanist commitment’ (

Riggs 2003, p. 143), postmodernity is a cultural paradigm which is often approached with scepticism and apprehension among Christian denominations. For religion, relative ontologies, social constructivism, and postmodern standpoints ‘would unacceptably pluralise knowledge into a multiplicity of incommensurable positions, vanquishing the unity of knowledge and the concept of grounded truth’ (

Gironi 2012, p. 27).

In particular, Catholicism in general does not appear to be ready to renew or reform its traditions in the postmodern spirit, but to perfect their existing structures under the guidance of Jesus Christ (

Asselin 1997, p. 25). In the same wave, Orthodoxy raises considerable concerns over the ontological compatibility of such relativist theoretical frameworks with its religious teachings. The relativistic and plural attitude of postmodernity is irreconcilable with the normative and doctrinal truth of Orthodox theology, asserting that ‘postmodernism heralds the end of truth, and that it undermines the Christian faith’ (

Walker 2010, p. 1). If modernism displaces God as the supernatural monarch, postmodernity deconstructs and recreates the traditional language, structures, and symbols of faith in a manner which espouses the original meanings in favour of a ‘plethora of pseudo-realities’ (

Walker 2010). Protestantism, on the other hand, espousing the ideals of humanism and critical judgment, has embraced Christian and ancient secular philosophy, empowering the individual to be critical and think for themselves (

Riggs 2003). This critical and personal approach to God is still evident in Anglican society in which secularization has taken hold since 1960s. In this context, religious education was transformed into ethics or the study of the world’s religions while by 2000, Anglican churches had become pluralistic both in doctrinal and ethical matters (

Bray 2007).

Protestantism lost confidence in the dogmatic depiction of the readings of the Bible, embracing hermeneutic philosophy for greater or lesser degree of sophistication’ (

Webster 1998, p. 307). But, hermeneutics has been vigorously challenged by Orthodox theologians, both as a method of interpreting biblical texts and a worldview. In particular, Orthodoxy is reluctant in its biblical criticism (in the custom of hermeneutical theology) asserting that the true meaning of the Bible is intelligible to the readers from different periods (

Radford 1991). Additionally, it rejects the premise that religious texts are historical entities, approaching them as testimonials of the revealed truth, transmitting the thoughts of their authors (

Bestebreurtje 2014). Similarly, from an existential and philosophical standpoint, the concepts of ‘heritagisation’, ‘museumification’ and ‘desacralisation’ seem to be alien to the Orthodox Christian cultural paradigm. Thus, the complete secularisation of an Orthodox temple is an unacceptable practice. The sacred art demands veneration, love and devotion to function as a sacrament (

Kenna 1985, p. 359;

McGuckin 2008, p. 273). It is evident that the rejection of hermeneutics, as an essential theoretical underpinning of the postmodern cultural paradigm and New Museology, reflects the aversion of Orthodoxy towards postmodernist strategies aimed at recontextualizing the meanings of religious sites to meet visitors ‘secular needs’.

10. Recognition and Reconciliation

Religious tourism education is a growing practice witnessed in western Christianity, while the Orthodox east executes tentative steps in constituting churches as places of educational regeneration in the broader context of social enculturation. In this context, the Protestant and Catholic churches execute considerable efforts in this direction, aiming at consolidating churches as welcoming heterogenous audiences. Anglican churches place considerable emphasis on launching learning programs in which ‘people will learn about and grow in Christian faith’ (see

York Minister Plan n.d.). As in the United Kingdom, non-statutory guidance of religious education in schools argues religious education ‘must be balanced promoting the spiritual, moral, cultural, mental and physical development of pupils and of society’ (

Department for Children, Schools and Families 2010, p. 4) in an attempt to marry the modernist/didactic with the postmodernist/constructivist frames in some ways. Equally, Cerezales informed us of how the Catholic Church acknowledges the power of religious art to enlighten visitors, reconstructing the connection between the authentic message of religious art and the visitors, which has been lost within the margins of secularization (

Cerezales 2011, p. 352). Additionally, in the Greek Orthodox world (Greece and Cyprus) the number of churches and monasteries hosting exhibitions, galleries and displays portraying the Byzantine past is growing. However, as the data demonstrate, the way meanings are negotiated and presented suggests that the reality of religious tourism education, has been received with several levels of resistance among the three denominations.

The three interpretive paradigms encountered in European Christian churches demonstrate how these denominations can adjust their tradition to the current curatorial practices. Examples from the first and second interpretative paradigms can be found in all three denominations, as the decision regarding the strategy of the interpretation (and in general public outreach) remains at the discretion of the local diocese. It is not unusual that because of the rigid hierarchical management structures of churches, site managers (comprised of professional clergy usually not trained in tourism) rely on ecclesiastical management structures largely unaffected by modern management trends (

Olsen 2009). However, the research revealed that examples of the postmodern third paradigm are to be found predominantly in the Anglican churches of the United Kingdom. On the contrary, Orthodox churches, emphasizing the sanctity of the place, favour the first interpretive paradigm, while Catholic churches, which seem more content with the concept of heritagization, occupy the second paradigm. Conclusively, interpretative strategies encountered in Christian churches reveal a reciprocal relationship between religious tradition and the current postmodern curatorial practices. In this model, it is evident that the conservatism of a Christian denomination in adapting the New Museological practices is the result of how congenial a denomination is towards the ‘ethics’ of the dominant postmodern cultural paradigm. Thus, the more a denomination shows evidence of adaptability to the postmodern cultural paradigm, claiming for polysemy and plurality, (such as the Anglican churches of Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s Cathedral) the more flexible it appears to be in experimenting with New Museological practices in conveying the intended messages.

A possible explanation for their aforementioned causality may be the difficulty of postmodern curatorial practices to gain ground in religious settings. Overall, there seems to be some evidence to indicate that the difficulty of framing religious connotations under the engaging and holistic postmodern cultural paradigm is the result of an ontological plurality at play. On the one hand, the postmodern cultural paradigm envisages a world in which religious heritage is reinterpreted and recontextualized in the broader contemporary social and cultural frame of reference. This is a conscious strategy aiming to meet the constantly changing needs of present day visitors or in Beck and Cable‘s words, ‘interpreters must relate the subject to the lives of the audience’ (

Beck and Cable 2002, p. 8). On the other hand, most Christian denominations are sceptical over such endeavours, postulating for a space with eternal and unchangeable meanings. Thus, it is important to consider the compatibility of ‘New Museology’ advocating for multiple narratives and polysemy with that of religious realism. As A. Moore noted, ‘doctrinal outlooks of particular religions will require their realism to be defended in ways appropriate to their own particular ontological commitments’ (

Moore 2003, p. 7). This leads us to what Harrison characterized as ontological plurality, ‘that different forms of heritage practices enact different realities and hence work to assemble different futures’ (

Harrison 2015, p. 24). As a result, Orthodox and Catholic churches appear to embrace what Jennifer Gardon Smith described as ‘high culture’ (a strategy in which the visitor in not a co-participant in meaning making), emphasizing the authenticity, pedagogy and the enduring and verifiable nature of the presented object (

Smith 1999).

Religious tourism studies ought to shift the attention from visitors, as key components in shaping religious tourism education, to the cultural and social structures underlying heritagization. It is only by expanding the interpretative communities at play, those ‘using common interpretive strategies’ (

Greenhill 1994, p. 13), and acknowledging their perspectives that the various forces shaping the collective phenomenon of heritagization will be unveiled. The dialogue between heterogenous groups, such as church and secular bodies (ranging from enterprises to local, national and international institutions), will be fostered by developing new forms of heritage that ‘model such connectivity of ontologies’ while considering the various ontological fields and visions for the future (

Harrison 2015, p. 24). As Bryman stated, ‘social ontology cannot be divorced from issues concerning the contact of social research’ (

Bryman 2012, p. 34). By acknowledging the ontological perspectivism at play, various perspectives which have been passed over unnoticed in the fast-growing secularization of religious sites will be revealed. For instance, Orthodoxy‘s preferable ‘modernist’ linear interpretations of privileging facts over polysemy should not simply be regarded as an obsolete ‘modernist’ heritage practice favouring historical and archaeological facts, but rather as a defensive mechanism against the thread of the commodification of their sacraments (see

Uzzell and Ballantyne 1998;

Carnegie 2009). Holy icons are non-verbal religious and symbolic forms of communication which retain their sanctity through worshippers’ veneration. During the process of heritagization of a religious space, this direct and immediate relationship with the worshiper is broken (

Kokosalakis 1995). Hence. any heritage practice which materializes, aestheticizes and subjectifies the Byzantine pictorial art, runs the risk of desacralizing the holiness of the place.

Although some strategies advocated by New Museology have infiltrated Protestant churches in their long transformation since the Reformation, the data demonstrate that ‘New Museology’ does not seem to have reconciled fully with Christianity. Religious sites aiming to present a holistic experience to visitors, utilizing religious connotations, should demonstrate that they convey multiple narratives and are diverse and empathetic towards other perspectives. Although the road towards revelatory interpretations (presenting both the tangible and intangible nature of ecclesiastical heritage) at religious sites is open, critical active engagement has not yet been reached. As Di Giovine and Garcia-Fuentes have noted, heritagization is inherently a political act, a process in which secular and aesthetic aspects of religious relics are privileged over the spiritual (

Di Giovine and Garcia-Fuentes 2016). Although this article embraces the engaging and stimulating strategies of a postmodern cultural paradigm, it also acknowledges that it envisages a cultural ideology which is variant with religion. Consequently, this article is sceptical about the capacity of museum theory, framed under the postmodern cultural paradigm, including a wide range of expectations and beliefs, to propose an interpretational paradigm which will reintroduce faith (as the intangible aspect of ecclesiastical heritage) in public discourse. Similar scepticism regarding the applicability of New Museology has been noted in secular context. As Smith stated, ‘heritage is used to construct, reconstruct and negotiate a range of identities and social and cultural values and meanings in the present’ (

Smith 2006, p. 3). In this context, it is important for the research to shift the attention to stakeholders and to understand how religion as an institution envisages the future of religious and heritage sites, the preservation of their identities, and the public discourse over religion, either as a system of belief or a cultural tradition. As Kurmanaliyeva et al. stated, churches as a common cultural landscape, shared between religion and tourism, call for a mutually beneficial dialogue (

Kurmanaliyeva et al. 2014). In this line of thought, this article calls for a new interpretational paradigm which will acknowledge the power of stakeholders to shape the spiritual and cultural profile of religious sites while it promulgates religious tourism education to be informative, relevant and engaging to heterogenous groups.