Dai Identity in the Chinese Ecological Civilization: Negotiating Culture, Environment, and Development in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Political and Theoretical Considerations

3. Research among Ethnic Minority Dai in Xishuangbanna

4. Ethnic Rankings and Ideological Landscapes

Thus, whereas ethnic minorities and their land use practices were previously denigrated as uncivilized and environmentally harmful, their contemporary branding is much more positive. At the same time, the ethnic minorities remain the objects of civilizing campaigns in the form of well-intentioned conservation initiatives. Throughout my fieldwork, I met passionate researchers and officials committed to working with local communities and teaching villagers how to protect the environment. State-funded research projects and conservation initiatives in China and Southeast Asia have been meticulously conducted to explore intercropping and other agroforestry techniques in monoculture rubber plantations as a means of reducing environmental and economic risks (e.g., Commercon 2016; Min et al. 2017; Penot et al. 2017; Dove 2018), but in Xishuangbanna, ethnicity has been identified as one of the “[m]ajor factors of adoption” (Min et al. 2017, p. 223) for these improved cultivation practices among smallholder rubber farmers. Agroforestry, meanwhile, has long been practiced by ethnic minority farmers in Xishuangbanna before and throughout the advent of rubber (Saint-Pierre 1991). Thus, although the content of the Eco-Civilization dogma has ostensibly altered narratives surrounding ethnic minorities, the embedded power dynamics between the central state as the civilizing center and rural ethnic minorities as peripheral peoples remain unchanged. Furthermore, as the following sections will also illustrate, initiatives and institutions inspired by Eco-Civilization often neglect to treat ethnic minorities as the experts of their own cultures, nor do they trust ethnic minority traditions in the hands of ethnic minorities themselves.Over thousands of years, traditional multifunctional agriculture, originally maintained by village and small household farming, was able to develop and apply what are essentially systems of eco-environmental sustainability. This has been gradually recognized as important, not because of modern education or mainstream institutions, but because of the challenges of global warming in adversely affecting yields and incidents of low food safety and quality. Most developing countries and regions in Asia, like rural China, have regional agriculture that can be congruent with the characteristics of nature of heterogeneity and diversity that will be essential for an ecological civilization.

5. Holy Hill Eco-Tourism and the Development Catch-22

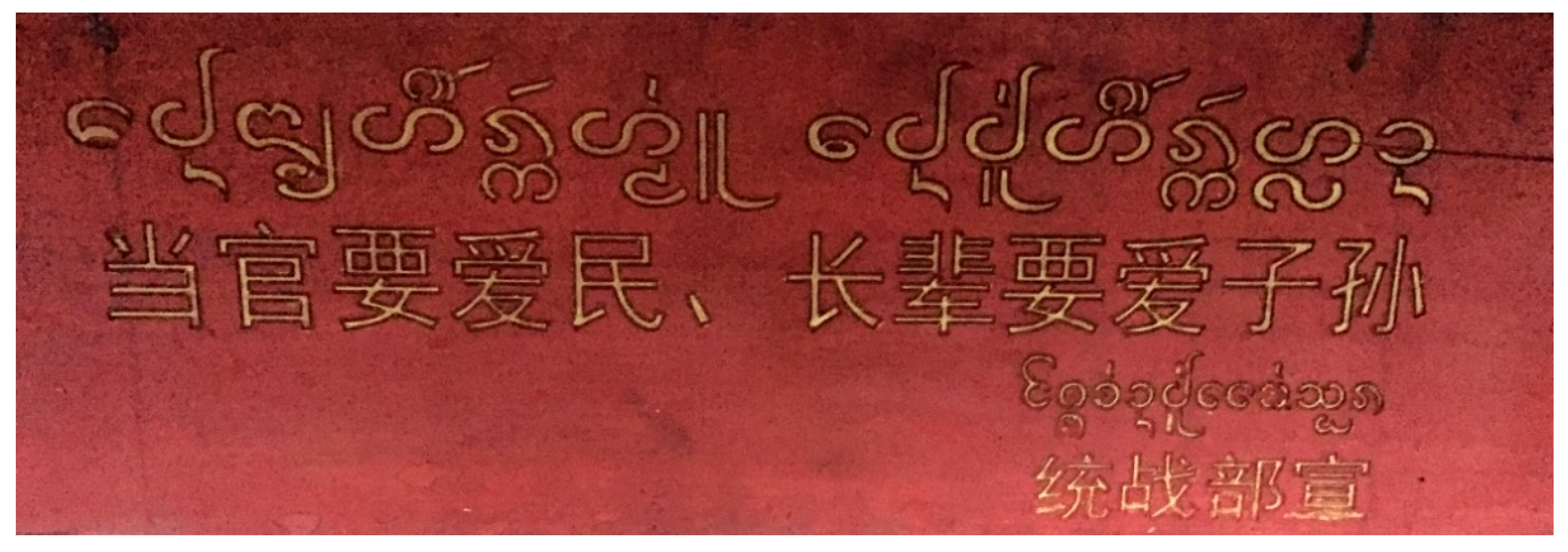

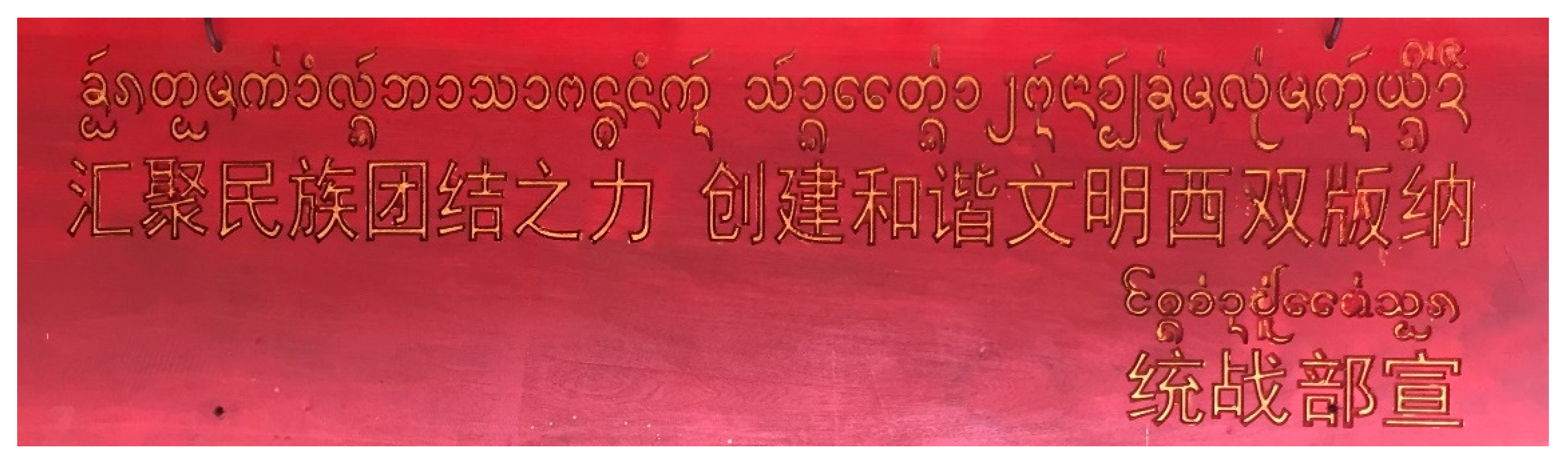

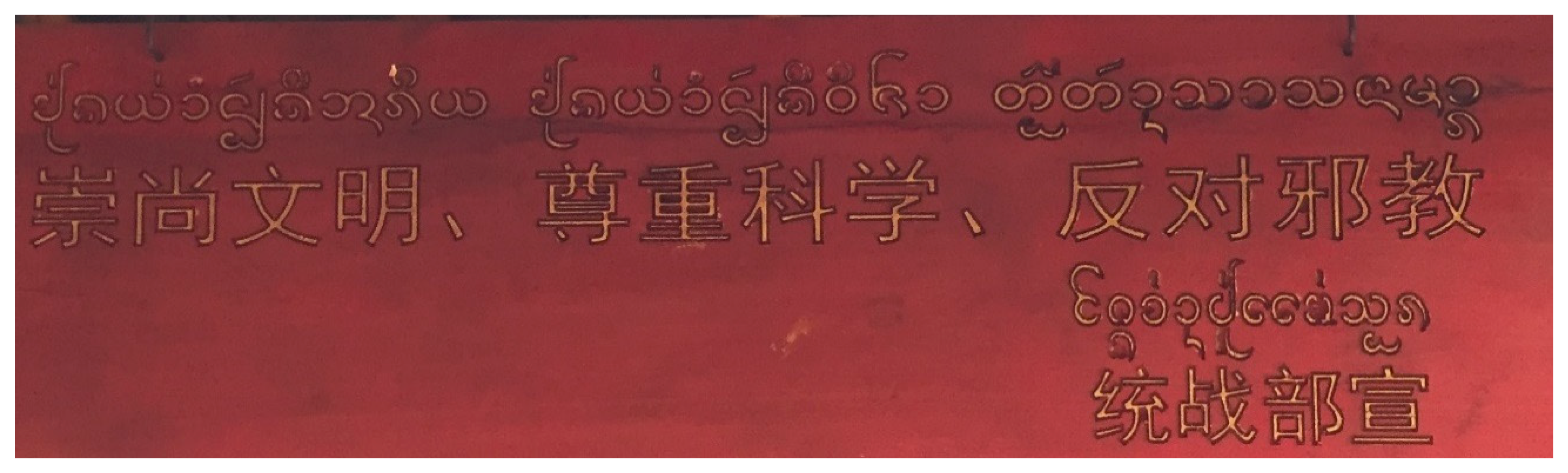

6. Eco-Civilization in Public Signage and Parent-Child Dynamics

it not only demonstrates the inferiority of peripheral peoples, but also certifies their civilizability, and thus legitimates not just domination but the particular kind of domination we call a civilizing project. … since children are by definition both inferior and educable, the peripheral peoples represented as childlike are both inferior and civilizable, and it becomes the task of the center to civilize them.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahlers, Anna L., and Yongdong Shen. 2018. Breathe Easy? Local Nuances of Authoritarian Environmentalism in China’s Battle against Air Pollution. China Quarterly 234: 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnost, Ann. 2004. The Corporeal Politics of Quality (Suzhi). Public Culture 16: 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Lauren, Michael Dove, Dana Graef, Alder Keleman, David Kneas, Sarah Osterhoudt, and Jeffrey Stoike. 2013. Whose Diversity Counts? The Politics and Paradoxes of Modern Diversity. Sustainability 5: 2495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, Steven. 2001. The Compromise of Liberal Environmentalism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, Thomas. 2008. Worry for the Dai Nation: Sipsongpannā, Chinese Modernity, and the Problems of Buddhist Modernism. The Journal of Asian Studies 67: 107–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Min, Hu Huabin, Yong Tang, and Xianhui Fu. 2000. Human Dimension of Tropical Forest in Xishuangbanna, SW China. In 2000 Seminar on Ecosystem Research and Sustainable Management. Seoul: Korea Long-Term Ecological Research Network. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Huafang, Zhuangfang Yi, Dietrich Schmidt-Vogt, Antje Ahrends, Philip Beckschäfer, Christoph Kleinn, Sailesh Ranjitkar, and Jianchu Xu. 2016. Pushing the Limits: The Pattern and Dynamics of Rubber Monoculture Expansion in Xishuangbanna, SW China. PLoS ONE 11: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commercon, Francis. 2016. Local Knowledge for Restoration in a Rubber-Dominated Landscape in SW China. Available online: http://blog.worldagroforestry.org/index.php/2016/01/26/local-knowledge-for-restoration-in-a-rubber-dominated-landscape-in-china/ (accessed on 8 September 2016).

- Conklin, Harold C. 1954. An Ethnoecological Approach to Shifting Agriculture. Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences II 17: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, Harold C. 1957. Hanunóo Agriculture: A Report on an Integral System of Shifting Cultivation in the Philippines. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, William. 1995. The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. Environmental History 1: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle, Helen F. Siu, and Donald S. Sutton, eds. 2006. Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Sara L. M. 2005. Song and Silence: Ethnic Revival on China’s Southwest Borders. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delman, Jørgen. 2018. Ecological Civilization Politics and Governance in Hangzhou: New Pathways to Green Urban Development? Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 16: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dove, Michael R. 1983. Theories of Swidden Agriculture, and the Political Economy of Ignorance. Agroforestry Systems 1: 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, Michael R. 2018. Rubber versus Forest on Contested Asian Land. Nature Plants 4: 321–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duara, Prasenjit. 2001. The Discourse of Civilization and Pan-Asianism. Journal of World History 12: 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duara, Prasenjit. 2014. The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian Traditions and a Sustainable Future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dynon, Nicholas. 2008. ‘Four Civilizations’ and the Evolution of Post-Mao Chinese Socialist Ideology. China Journal 60: 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Grant. 2000. Transformation of Jinghong, Xishuangbanna, PRC. In Where China Meets Southeast Asia: Social and Cultural Change in the Border Regions. Edited by Grant Evans, Christopher Hutton and Kuah Khun Eng. New York: St. Martin’s Press, pp. 162–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Lishi. 2010. A Study of the Long Forest Culture of the Dai People. Kunming: Yunnan Minzu Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Giersch, C. Patterson. 2006. Asian Borderland: The Transformation of Qing China’s Yunnan Frontier. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gladney, Dru C. 2004. Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Huijun, and Christine Padoch. 1995. Patterns and Management of Agroforestry Systems in Yunnan: An Approach to Upland Rural Development. Global Environmental Change 5: 273–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Huijin, Christine Padoch, Kevin Coffey, Chen Aiguo, and Fu Yongneng. 2002. Economic Development, Land Use and Biodiversity Change in the Tropical Mountains of Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, Southwest China. Environmental Science & Policy 5: 471–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Mette Halskov. 1999. Lessons in Being Chinese: Minority Education and Ethnic Identity in Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Mette Halskov. 2005. Frontier People: Han Settlers in Minority Areas of China. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Mette Halskov, and Zhaohui Liu. 2018. Air Pollution and Grassroots Echoes of ‘Ecological Civilization’ in Rural China. China Quarterly 234: 320–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Mette Halskov, Hongtao Li, and Rune Svarverud. 2018. Ecological Civilization: Interpreting the Chinese Past, Projecting the Global Future. Global Environmental Change 53: 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, Stevan. 1995a. Civilizing Projects and the Reaction to Them. In Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers. Edited by Stevan Harrell. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, Stevan, ed. 1995b. Cultural Encounters on China Ethnic Frontiers. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Paul G., and Graeme Lang, eds. 2015. Routledge Handbook of Environment and Society in Asia. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, Kiyoshi. 2000. Cultural Revival and Ethnicity: The Case of the Tai Lüe in the Sipsong Panna, Yunnan Province. In Dynamics of Ethnic Cultures Across National Boundaries in Southwestern China and Mainland Southeast Asia: Relations, Societies and Languages. Edited by Yukio Hayashi and Guangyuan Yang. Chiang Mai: Ming Muang Publishing House, pp. 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway, Michael J. 2013. Environmental Winds: Making the Global in Southwest China. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Flora Lu. 2005. The Catch-22 of Conservation: Indigenous Peoples, Biologists, and Cultural Change. Human Ecology 33: 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Shih-Chung. 1995. On the Dynamics of Tai/Dai-Lue Ethnicity: An Ethnohistorical Analysis. In Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontier. Edited by Stevan Harrell. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 301–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Huabin, Wenjun Liu, and Min Cao. 2008. Impact of Land Use and Land Cover Changes on Ecosystem Services in Menglun, Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 146: 147–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, Charles F. 1992. Who Are the Lue? Revisited: Ethnic Identity in Laos, Thailand, and China. In Working Paper, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for International Studies. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for International Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, Charles F. 1995. Who Are the Tai? Reflections on the Invention of Identities. In Ethnic Identity: Creation, Conflict and Accommodation, 3rd ed. Edited by Lola Romanucci-Ross and George A. De Vos. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 130–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kostka, Genia, and Jonas Nahm. 2017. Central-Local Relations: Recentralization and Environmental Governance in China. China Quarterly 231: 567–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z. T., and H. Zhang. 1987. A Herpetological Report of Xishuangbanna. In Proceedings of Synthetical Investigation of Xishuangbanna Nature Reserves. Kunming: Yunnan Science and Technology Press, pp. 350–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lélé, Sharachchandra M. 1991. Sustainable Development: A Critical Review. World Development 19: 607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Hongmei, T. Mitchell Aide, Youxin Ma, Wenjun Liu, and Min Cao. 2007. Demand for Rubber Is Causing the Loss of High Diversity Rain Forest in SW China. Biodiversity and Conservation 16: 1731–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzinger, Ralph A. 2000. Other Chinas: The Yao and the Politics of National Belonging. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Hongmao, Zaifu Xu, Youkai Xu, and Jinxiu Wang. 2002. Practice of Conserving Plant Diversity through Traditional Beliefs: A Case Study in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Biodiversity and Conservation 11: 705–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, Susan K. 2009. Communist Multiculturalism: Ethnic Revival in Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Shi, Jikun Huang, Junfei Bai, and Hermann Waibel. 2017. Adoption of Intercropping among Smallholder Rubber Farmers in Xishuangbanna, China. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 15: 223–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Xiao Xue, Hua Zhu, Yong Jiang Zhang, J. W. Ferry Slik, and Jing Xin Liu. 2011. Traditional Forest Management Has Limited Impact on Plant Diversity and Composition in a Tropical Seasonal Rainforest in SW China. Biological Conservation 144: 1832–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullaney, Thomas S. 2010. Coming to Terms with the Nation: Ethnic Classification in Modern China. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Norman, Russell A. Mittermeier, Cristina G. Mittermeier, Gustavo A. B. da Fonseca, and Jennifer Kent. 2000. Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities. Nature 403: 853–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, James P. F. 2014. What Does Eco-Civilisation 生态文明 Mean? The China Story Journal 4: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Shengji. 1985. Preliminary Study of Ethnobotany in Xishuang Banna, People’s Republic of China. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 13: 121–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Shengji. 1993. Managing for Biological Diversity in Temple Yards and Holy Hills: The Traditional Practices of the Xishuangbanna Dai Community, Southwestern China. In Ethics, Religion, and Biodiversity: Relations between Conservation and Cultural Values. Edited by Lawrence S. Hamilton and Helen F. Takeuchi. Cambridge: White Horse Press, pp. 112–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Shengji. 2010. The Road to the Future? The Biocultural Values of the Holy Hill Forests of Yunnan Province, China. In Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture. Edited by Bas Verschuuren. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, pp. 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, Shengji, and Jianchu Xu. 1997. Biodiversity and Sustainability in Swidden Agroecosystems: Problems and Opportunities (a Synthesis). In Collected Research Papers on Biodiversity in Swidden Agroecosystems in Xishuangbanna. Edited by Shengji Pei. Kunming: Yunnan Education Publishing House, pp. 173–77. [Google Scholar]

- Penot, Eric, Bénédicte Chambon, and Gede Wibawa. 2017. History of Rubber Agroforestry Systems Development in Indonesia and Thailand as Alternatives for Sustainable Agriculture and Income Stability. International Proceedings of IRC 2017 1: 497–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Jane. 2009. Where the Rubber Meets the Garden. Nature 457: 246–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, Pavit. 2005. Xishuangbanna Biodiversity Conservation Corridors Project. People’s Republic of China: Pilot Site Project Profile. Bangkok: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Reuse, Gaetan. 2010. Secularization of Sacred Space: An Analysis of Dai Farmers Planting Rubber Trees on Holy Hills in Xishuangbanna. Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, Yunnan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Pierre, C. 1991. Evolution of Agroforestry in the Xishuangbanna Region of Tropical China. Agroforestry Systems 13: 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, Jon. 2015. Ecological Civilization: Proceedings, International Conference on Ecological Civilization and Environmental Reporting. Beijing: Yale Center Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, Louisa. 1997. Gender and Internal Orientalism in China. Modern China 23: 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Judith. 2001. Mao’s War against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Qingji. 2013. Study on New Urbanization Based on Ecological Civilization. Urban Planning Forum 206: 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sissons, Jeffrey. 2005. First Peoples: Indigenous Cultures and Their Futures. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, Mark David. 1999. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Richard. 2008. Beijing Olympics: ‘Ethnic’ Children Revealed as Fakes in Opening Ceremony. The Telegraph, August 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon, Janet C. 2004. Post-Socialist Property Rights for Akha in China: What Is at Stake? Conservation & Society 2: 137–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon, Janet C. 2010. Governing Minorities and Development in Xishuangbanna, China: Akha and Dai Rubber Farmers as Entrepreneurs. Geoforum 41: 318–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, Janet C., and Nicholas Menzies. 2006. Ideological Landscapes: Rubber in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, 1950 to 2007. Asian Geographer 25: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, Janet C., Nicholas K. Menzies, and Noah Schillo. 2014. Ecological Governance of Rubber in Xishuangbanna, China. Conservation and Society 12: 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, Stig. 2003. Parasites or Civilisers: The Legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party in Rural Areas. China: An International Journal 1: 200–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, Stig. 2009. Revisiting a Dramatic Triangle: The State, Villagers, and Social Activists in Chinese Rural Reconstruction Projects. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 38: 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsing, Anna. 1999. Becoming a Tribal Elder, and Other Green Development Fantasies. In Transforming the Indonesian Uplands: Marginality, Power, and Production. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, pp. 159–202. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. 2016. Green is Gold: The Strategy and Actions of China’s Ecological Civilization. Nairobi: UNEP. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Gungwu. 1984. The Chinese Urge to Civilize: Reflections on Change. Journal of Asian History 18: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Fayun, and Qiwu Duan. 1996. Helping Local People Establish an Ecological Model Village. Yunnan Daily Report, March 11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T., and B. Jin. 1987. Mammals in Xishuangbanna Area and a Brief Survey of Its Fauna. In Proceedings of Synthetical Investigation of Xishuangbanna Nature Reserves. Edited by Y. Xu, H. Jiang and F. Quan. Kunming: Yunnan Science and Technology Press, pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhijun, and Stephen S. Young. 2003. Differences in Bird Diversity between Two Swidden Agricultural Sites in Mountainous Terrain, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China. Biological Conservation 110: 231–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Gungwu, and Yongnian Zheng. 2000. Reform, Legitimacy, and Dilemmas: China’s Politics and Society. Singapore: Singapore University Press and World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Tiejun, Kinchi Lau, Cunwang Cheng, Huili He, and Jiansheng Qiu. 2012. Ecological Civilization, Indigenous Culture, and Rural Reconstruction in China. Monthly Review 63: 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Zhaolu, Hongmao Liu, and Linyun Liu. 2001. Rubber Cultivation and Sustainable Development in Xishuangbanna, China. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 8: 337–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jianchu. 2006. The Political, Social, and Ecological Transformation of a Landscape. Mountain Research and Development 26: 254–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jianchu, Shengji Pei, and Sanyang Chen. 1997. Indigenous Swidden Agroecosystems in Mengsong Hani Community. In Collected Research Papers on Biodiversity in Swidden Agroecosystems in Xishuangbanna. Kunming: Yunnan Education Press, pp. 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Jianchu, Jefferson Fox, Lu Xing, Nancy Podger, Stephen Leisz, and Ai Xihui. 1999. Effects of Swidden Cultivation, State Policies, and Customary Institutions on Land Cover in a Hani Village, Yunnan, China. Mountain Research and Development 19: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jianchu, Erzi T. Ma, Duojie Tashi, Fu Yongshou, Lu Zhi, and David Melick. 2005. Integrating Sacred Knowledge for Conservation Culture and Land Scape in Southwest China. Ecology and Society 10: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., T. Xie, Y. Duan, W. Xu, and H. Zhu. 1987. On Birds from Xishuangbanna. In Proceedings of Synthetical Investigation of Xishuangbanna Nature Reserves. Edited by Y. Xu, H. Jiang and F. Quan. Kunming: Yunnan Science and Technology Press, pp. 326–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Emily T. 2013. Taming Tibet: Landscape Transformation and the Gift of Chinese Development. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Emily T., and Christopher R. Coggins, eds. 2014. Mapping Shangrila: Contested Landscapes in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Shaoting. 2001. People and Forests: Yunnan Swidden Agriculture in Human-Ecological Perspective. Kunming: Yunnan Education Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Lily. 2012. Dai Holy Hills: Potential Sanctuaries of Botanical Biodiversity in Xishuangbanna, SW China. New Haven: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Lily. 2018a. Problematizing Ideas of Purity and Timelessness in the Conservation Narratives of Sacred Groves in Xishuangbanna, China. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 12: 172–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Lily. 2018b. Transformations of Indigenous Identity and Changing Meanings of Sacred Nature in Xishuangbanna, China. Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, New Haven. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Lily, and Gaetan Reuse. 2016. Holy Hills: Sanctuaries of Biodiversity in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. In Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and Practice in Protected Areas and Conservation. Edited by Bas Verschuuren and Naoya Furuta. London: Routledge, pp. 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Lily, Deepti Chatti, Chris Hebdon, and Michael R. Dove. 2017. The Political Ecology of Knowledge and Ignorance. Brown Journal of World Affairs 23: 159–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jianhou, and Min Cao. 1995. Tropical Forest Vegetation of Xishuangbanna, SW China and Its Secondary Changes, with Special Reference to Some Problems in Local Nature Conservation. Biological Conservation 73: 229–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jia-Qi, Richard T. Corlett, and Deli Zhai. 2019. After the Rubber Boom: Good News and Bad News for Biodiversity in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, China. Regional Environmental Change 19: 1713–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., Z. F. Xu, H. Wang, and B. G. Li. 2004. Tropical Rain Forest Fragmentation and Its Ecological and Species Diversity Changes in Southern Yunnan. Biodiversity and Conservation 13: 1355–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., H. Wang, and S. S. Zhou. 2010. Species Diversity, Floristic Composition and Physiognomy Changes in a Rainforest Remnant in Southern Yunnan, China after 48 Years. Journal of Tropical Forest Science 22: 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, Alan D., Jefferson M. Fox, and Jianchu Xu. 2009. The Rubber Juggernaut. Science 324: 1024–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Shih-chung Hsieh describes the 1951 meeting in which Dai group representatives met in Beijing to discuss the Mandarin Chinese name for their people: “The representatives of Dehong suggested using Tai 泰 (as their name for themselves still is pronounced), but the Xishuangbanna members wanted to adopt a word with the sound dai. Finally, to settle the quarrel, Prime Minister Zhou Enlai synthesized the character 泰 and the radical 人 (which means “people”) to create Dai 傣” (Hsieh 1995, p. 319). |

| 4 | “Tai” is not to be confused with “Thai,” which usually refers to Tai-speaking peoples in Thailand or citizens of Thailand. |

| 5 | In particular, Dai includes Tai Lue, who span Xishuangbanna and other Southeast Asian countries, and Tai Neua, from the Dehong region of western Yunnan province. These groups did not share the same premodern genealogies or writing systems, and their spoken languages and writing systems, though linguistically related, are not mutually comprehensible (Keyes 1992; Hsieh 1995; Davis 2005). |

| 6 | This territory was divided into twelve (sipsong in Dai language) political entities called panna (pan means thousand and na means rice paddy in Dai language; the panna political territory is based on the idea of “one thousand rice paddies”)—hence the name “Sipsongpanna” (Reuse 2010). However, Dai interlocuters have often remarked to me that only eight of the original twelve panna territories are part of China’s Xishuangbanna—the remainder of which comprise parts of Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand—which has led to a joke among some Dai people that Xishuangbanna ought to be named “Baetbanna” (baet meaning eight in Dai language). |

| 7 | The rest would be on Hainan Island, the only other location with tropical climate in China. |

| 8 | These sentiments are not ubiquitous and continue to change among Dai rubber producers, particularly as Dai smallholder farms become more economically successful and state rubber farms stagnate (see Sturgeon 2010). |

| 9 | Of course, Han migrants to Xishuangbanna are not a homogenous group. Hansen (2005) describes distinctions between state-organized Han migrants who arrived to Xishuangbanna during the Maoist era and independent Han migrant who came in the reform era in search of economic opportunities, as well as class differences within these groups. |

| 10 | This process was reminiscent of the creation of national parks in the USA in the late-1800s, beginning with the forcible removal of Native Americans from Yellowstone National Park to allow tourists and preservationists an unmarred experience of wilderness (Cronon 1995; Spence 1999). |

| 11 | It was later revealed that these children were not in fact from the various ethnic minority groups; they were Han children wearing costumes representing each ethnic minority (Spencer 2008). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, L. Dai Identity in the Chinese Ecological Civilization: Negotiating Culture, Environment, and Development in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Religions 2019, 10, 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10120646

Zeng L. Dai Identity in the Chinese Ecological Civilization: Negotiating Culture, Environment, and Development in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Religions. 2019; 10(12):646. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10120646

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Lily. 2019. "Dai Identity in the Chinese Ecological Civilization: Negotiating Culture, Environment, and Development in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China" Religions 10, no. 12: 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10120646

APA StyleZeng, L. (2019). Dai Identity in the Chinese Ecological Civilization: Negotiating Culture, Environment, and Development in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Religions, 10(12), 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10120646