4.1. Multiple Hues of Anger

While identifying various forms of anger, we want to emphasize the interactivity and fluidity among them—and between anger and other emotions. To this end, we employ a primary metaphor of a color spectrum [

Figure 1], which represents relationships among many hues. Hue specifies color, which is determined by a dominant wavelength of light. Blue is a different hue than orange. Yet even within blues there are multiple hues or shades: cobalt, sky blue, navy, and so on. Analogously, anger differs from joy, on any account. Yet even within anger there are different hues. The definition of hue includes the adjective ‘dominant’ because, in nature, light that comprises a given color is not monochromatic but is rather a mixture of wavelengths with a primary wavelength having more influence than the others on visual receptor cells. Similarly, people with emotional intelligence can identify a dominant emotion, even as they believe that they are experiencing a few others at the same time or shifting from one to another. A dominant emotion can be understood roughly as the way of being moved that commands most of a person’s attention and energy and, in many cases, best explains the way she behaves or, perhaps,

pictures herself behaving—if only the behavior in question were possible and permitted.

A widely recognized form of anger involves a desire for payback. However, one would not be warranted in assuming that the desire for payback is the central or most definitive form of anger. A group of people could be asked, for example, to pick out the standard color of blue or the bluest blue, among a variety of blues. Many of them would probably pick different hues. A given culture might identify one form of blue as normative, but some of its members might not assent to this judgment. And different cultures might be attached to different blues. Consider the brilliant (sea-colored) blue roofs on buildings in the Greek islands (

Shapka 2012) and compare the most common of those hues with the most prominent (sky-colored) hue in Argentina, which is actually called Argentinian blue (

Economist Staff 2017). It often makes sense, then, to refer to blues in the plural, and to say that blues comprise a wavelength spectrum from 450–495 nanometers, with 451 being just as blue as 494. Likewise, anger can take a variety of hues, which could be pointed to on a spectrum, none of which is, in principle, any less

anger than the others (

Schnell, forthcoming). One could refer to multiple hues of anger as

angers in order to disturb the idea that there exist a limited number of discrete forms of anger, some of which define the emotion better than others. However, for our purposes it is simpler to refer to

forms of anger, with the understanding that what we are doing is highlighting a few points on a spectrum of possible human experiences, and naming some common and distinguishing features of those experiences.

It is helpful to bring some voices from psychology into perspective. Ira J. Roseman analyzes anger by enumerating the multiple goals and functions that it can have. He refers to the “goals that people want to pursue when experiencing an emotion” as “emotivational goals” (

Roseman 2018, p. 148). With reference to other scholars, he specifies that “emotivational goals” can include “[removing] an obstruction (e.g., Frijda 1986; cf. Lench and Levine 2008), correcting some injustice (e.g., Averill 1982), or getting revenge (e.g., Aristotle 1966; Roseman 2011)” (

Roseman 2018, p. 148). Within any of these goals a person could potentially specify sub-goals. Referencing the research of Golwitzer et al., Roseman makes the point that a desire for revenge can aim more specifically at “(a) restoring status lost through victimization, and/or (b) obtaining reason to believe the offensive conduct will not be repeated (Gollwitzer et al. 2011)” (

Roseman 2018, p. 149).

Anger can have different goals, and thus feel differently, depending also on the person toward whom it is directed. Roseman observes that anger felt toward a loved one, such as a child or a parent, is rarely about revenge. He writes, “although revenge may sometimes be desired in parent-child anger, there are many cases in which it seems to play no part. If a parent is angry at a child for not cleaning his room, or a child at a parent for refusing to allow her to go to a party, the goal seems often to be influencing the target’s behavior (and if the behavior changes, anger is likely to diminish)” (

Roseman 2018, p. 149). It is in considering anger with respect to intimate relationships that it becomes clearest that “threatening [revenge] may not be integral to the goals of angry persons—making the target act (or not act) in a certain way seems more characteristic across instances” (

Roseman 2018, p. 149). That is to say, a more characteristic goals is that of “compelling another” to do or cease doing something (

Roseman 2018, p. 150). As we learn from Aquinas, some forms of anger involve a desire to

make an offender have a vivid experience of what it is like to have his will, including his free access to what he loves most, painfully constrained. However, there are other modes of wanting, in the face of an obstacle, to bend someone’s will or behavior toward our own interests. Part of the ‘heat’ of anger comes from the resistance to such bending that many persons put up.

In addition to addressing anger’s goals, Roseman compiles, from previous research, eight proposed functions of anger

Table 1—by functions, he means “correspond[ing] to the likely effect[s] of an emotion strategy in the type of situation which elicits that emotion” (

Roseman 2018, p. 152). He calls three of these functions general, and five of them specific (

Roseman 2018, pp. 152–53).

It is beneficial, here, to think of anger less as an object, such as a compass, whose needle points in one direction or another and functions to get a person to a desired location, and more as an experience that differs from other, similar experiences, depending on what the experience is centrally about, how it feels in one’s body, and what one most desires, in that embodied experience, to do.

We wish to highlight three hues of anger from a Thomistic perspective that considers the common good in light of historical misuses of power: payback-anger, protection-anger, and recognition-anger. Payback-anger has already been discussed, but let us make explicit what we mean by the term. On our view, payback-anger names a desire to rise up against a perceived offender and, by punishing him (or having someone else punish him), to compel him to pay a price for what he did. Payback-anger refers to a person’s desire to exact compensation from someone who caused her or someone else a wrongful injury—a desire that might simply feel like an impulse to pounce on the offender. As with other forms of anger, this desire is predominantly sensory in that it is evoked by sensory impressions and it is mediated by physiological changes. At the same time, even before such a desire arises, discursive thought is taking place, and thought occurs throughout the episode in ways that can be expected to make a difference to how a person feels—hence, the fluid relationship, noted previously, between a basic sense of inequity, which elicits predominantly sensory tending, and an increasingly intellectual judgment that this person has committed a wrong, which elicits a motion of the will geared toward righting the wrong.

Inasmuch as payback refers to the infliction of an evil as fair payment for an unjustified evil that a person inflicted on someone else, it is associated especially with the goal of retaliation, usually grounded in an appeal to

lex talionis. Yet the term can suggest, somewhat differently, a person or authority compelling an offender to return to a victim something important that he took from her. The image here is more of a good paid for a good taken, which tends to be associated with the goal of restitution. Granted, there can be evil involved even here in compelling a person to do something that he does not want to do. Payback can signify also a person freely giving to another what she believes the other is due—a kind of reparation, which includes not only the restoration of something taken, but also an offer to repair the relationship itself. Consider an example: A white member of the US community might be prepared to pay something desirable to the African American community for a theft that has long angered its members, including the historical exploitation of their bodies and labor in building a nation, access to whose full benefits many continue to be denied. The white person’s desire for reparation might not be motivated by her own anger per se. But it might be motivated by anger that she shares with African Americans, namely, a desire to compel white people to confront the history of racial oppression in the US and to recognize a duty to compensate for the horrors that their forebears inflicted, from which they themselves likely continue to benefit. The goal of this anger might be limited to restitution, but for some people it will also include the creation of new relationships between equals. It can admittedly be difficult to succeed in pressuring someone to make a free offer of civic friendship (

Cates 1996).

As noted above, we regard the desire to exact payback from an unwilling offender to be morally problematic inasmuch as it is tied to pleasing images of causing a fellow human being unwanted pain. Even if this desire is also a (more intellectual) desire for justice, and a person is pleased primarily at the possibility of justice, her being pleased with the image of inflicting pain is nonetheless regrettable. Perhaps it would be less regrettable if it were qualified by pain over the very need or the occasion to inflict pain. The desire for vengeance wrought through punishment is problematic partly because of its corrupting effects on the angry person’s character. It is all too easy for people who are pleased with another’s suffering to become comfortable with the act of inflicting pain or watching it be inflicted, and every day presents opportunities for the expression of dehumanizing callousness. The desire for vengeance wrought through punishment is problematic also because of the likelihood that it will exceed reasonable bounds and, moreover, propel a person or group to act in ways that are unproductive or mostly destructive. As Aquinas notes, a person is not in the best position to determine how much pain it is fair to inflict on an offender when she is already taking pleasure in the thought of that pain (

Aquinas 2012, I–II 48.3). This is not to say that a desire for payback that is accompanied by anticipatory pleasure cannot be justified, but only that it needs to be justified before a person could choose well to indulge it.

In assessing a particular case of such a desire, everything depends (for all agents involved) on the relevant particulars of the case, which can never adequately be specified in the abstract. Nevertheless, an example of a possibly justifiable payback-anger would be a desire to force someone, who appears to many people to care for no one but himself, to become painfully aware that he has done something wrong, and that his behavior will not be tolerated by the community—where an accompanying pleasure, if notable, concerns the restoration of the bonds of community on which everyone relies. This person will not be allowed to make an exception of himself. Payback-anger might, instead, be unjustifiable if, for example, it takes the form of a desire to slam someone down who is already suffering; if our desire is evoked by a minor slight; if it is much too intense for the circumstance and for our own good; if it is never satisfied or it grows inveterate; and so on. Aristotle’s apt image of an archer suggests that there are a lot of ways to miss the target completely when it comes to getting emotions right; relatively few ways to hit the target; and even fewer ways to hit the bull’s eye (

Aristotle 1985, 1094a23).

A second hue of anger worth highlighting is what we call

protection-anger. “If someone’s hurting my kid, I’m like a momma bear.” This familiar simile is born of the human interpretation of a bear’s act of rising up to protect her young when threatened, and trying to drive off the threat. Readers can view an example of this behavior in the following YouTube video (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcQomljKGNA). The mother bear has risen to action, roared her displeasure, and forced the intruding bear to back off. We expect most people to agree that the mother bear is not simply behaving angrily for effect; she desires to drive the other bear off and senses that, if she does not, her cubs will be injured. She does not want in her anger to hurt the other bear per se. Rather, she wants to compel him to leave her and her cubs alone, and she wants to deter him from coming back, sensing that she can best do this by threatening to inflict pain on him. Aquinas may implicitly identify this form of anger when he says that “[I]t is natural to everything to rise up against [and repel] things contrary and hurtful” (

Aquinas 2012, I–II 46.5, 48.2).

Shifting to the human situation, protection-anger, like other forms of anger, reveals a person’s vulnerability to harm. The person is either in imminent danger of a wrongful injury (which already, in a sense, counts as an injury to her security and sense of well-being) or she has been injured directly, and she senses, painfully, that she could be injured again if she does not do something to or against the offender. Many people’s desires to rise up against and compel the restraint of an offender’s ability to cause harm are not limited to themselves and their loved ones. Many people desire to protect strangers, including imprisoned criminals who, on their view, were wrongfully made extra-vulnerable by a lifetime of social harm and neglect, and are in greater danger than others of further injury. On a Thomistic view, this emotional extension is made via compassion (

misericordia), which has a basis in love, where love includes a bond of affection (

affectus) that makes it possible for one person to experience another person’s good (and also the evil that the other suffers) as partly her own (

Aquinas 2012, II–II 30.2; I–II 28.1 ad 2;

Cates 1997).

Like payback-anger, protection anger is not inherently good or bad. Again, the details of the circumstances matter, but a potentially justifiable form of such anger would be where a woman is angry at her abusive husband in a way that gives her the strength to leave him—and where her anger does not overly color her imagining and deliberating about how best to accomplish this end. Protection-anger can also take unjustifiable forms, as when a person is frequently, explosively angry and scares other people away in a tragic effort to make himself invulnerable to the sort of hurt that is an unavoidable feature of human love and intimacy. The desire is tragic because the person really does, on some level, want to be loved or at least shown affection.

A third hue of anger worth distinguishing is what we call

recognition-anger, which names a person’s desire to rise up against another person or group, which refuses to recognize her excellence, and somehow compel that recognition. Tarana Burke describes a teen, named Heaven, who was “filled with anger” at the way she was being treated by another person in her household, and who repeatedly sought Burke out for conversation and counsel. Burke writes,

Finally, later in the day she caught up with me and almost begged me to listen. I reluctantly conceded, and for the next several minutes this child, Heaven, struggled to tell me about her “stepdaddy”—rather, her mother’s boyfriend—who was doing all sorts of monstrous things to her developing body. I was horrified by her words, and the emotions welling inside of me ran the gamut.

I listened until I literally could not take it anymore, which turned out to be less than 5 min. Then, right in the middle of her sharing her pain with me, I cut her off and immediately directed her to another female counselor who could “help her better”.

I will never forget the look on her face.

I will never forget the look on her face because it haunts me. I think about her all of the time. The shock of being rejected, the pain of opening a wound only to have it abruptly forced closed again—it was all on her face. As much as I love children, as much as I cared about that child, I could not find the courage that she had found.

As much as I loved her, I could not muster the energy to tell her that I understood, that I connected, that I could feel her pain. I couldn’t help her release her shame or impress upon her that nothing that happened to her was her fault. I could not find the strength to say out loud the words that were ringing in my head over and over again as she tried to tell me what she had endured.

I watched her walk away from me as she tried to recapture her secrets and tuck them back into their hiding place. I watched her put her mask back on and go back into the world like she was all alone and I couldn’t even bring myself to whisper…me too.

Burke uses two short words to say, ‘I see you.’ More than that, she says, ‘I see you so much, I see myself.’ She is brought face to face with her own pain, buried somewhere beneath the “gamut,” which is now added to the pain that she already feels for Heaven, and she is awakened to her own anger to match the anger of Heaven. She experiences anger, not only at the fact that both of them have suffered sexual abuse, but also at the realization that countless women, throughout history and around the world have suffered similar abuse—much of it death-dealing. As the woman who initiated the ‘me too’ movement, Burke invites other women and humane men to awaken to their anger as well. One could say that Burke’s anger became partly a desire to create a tidal wave of women-centered power that was strong enough to compel every sexually abusive or enabling man to stand before her, Heaven, and every other woman, and experience the profound moral claim that her humanity makes on them. A person might not be realistic in embracing such a desire. It is very difficult to evoke genuine respect from masses of people who simply do not care about girls and women as persons—especially those who ignore responsible internet media. However, her desire can nonetheless become increasingly rational as she thinks about the way in which a lot of little changes can add up to big changes, if she learns from experience about what works and what does not, and if the ideal outcome that she desires is consistent with the judgment that respect for human dignity is a moral duty and a requirement of virtue.

Recognition-anger can easily overlap with pay-back anger, but it is different in that the person who experiences recognition-anger might not want to cause the other pain in order to exact payment for his wrongful attitudes and behavior. In addition, a person might desire to force an offender to respect her, but not in a way that returns the two of them to a previous status quo. Rather, she might desire to force the other to respect her for the first time, creating a more equitable playing field that has never existed before. Similarly, recognition-anger can easily overlap with protection-anger, but the person who experiences recognition-anger wants more than to drive an offender off, to secure her and others’ safety. She wants to enter into a different relationship with her offender. Granted, a person who feels this sort of anger might have been so abused that she hardly knows what being respected feels like; she hardly knows what a better relationship would look like. But she probably ‘knows’ in her gut, in her anger, that it feels better than constant erasure and degradation.

Like the others, recognition anger can be morally justifiable or unjustifiable. An example of a possibly good form of it would be a surge of self-confidence and power, in a victim, in the form of a desire to grab a misogynistic man by the scruff of the neck and force him, not simply to look at her, but to ‘see’ her for her excellence (

Flescher, forthcoming). As with other examples, the claim is not that acting in the desired way would be morally justified, but only that the desire to act in that way might be justifiable inasmuch as it is a reflection of a person’s rightful love for herself and other vulnerable humans. Nor is the claim that a person does well to stoke such anger in order to continue to feel empowered relative to people who shamelessly disrespect her; that would soon become injurious to her, rob her of love and joy in life, and effectively make her the other’s slave. The point is simply that such a desire

can be reasonable, under certain conditions; what she desires can be something that is good for her, in that moment, and good for the rest of the community.

An example of a more problematic form of recognition-anger would be the desire to force someone to take us seriously, but in a way that we do not deserve to be taken seriously. For example, without being fully aware of it, a person might desire that someone regard her as being at the center of his universe. She might tell herself that she wants simply to be regarded and treated as uniquely special by someone who has expressed his love for her; but a closer look reveals that what she really wants is to be regarded as a god—so that she never has to share her partner’s affection with anyone else, and she can maintain the illusion of being safe from the loss of his love. In such a case, the person is probably disposed to become angry whenever her beloved wants to do anything but submit to her narcissistic fantasy and her drive to compel.

In summary of this section, we have identified three forms of anger that are worth being able to distinguish inasmuch as distinguishing them helps a person to refine her ability to identify what she really wants and subject her actual desires to useful moral assessment, as needed. In connection to previous parts of the essay all of these forms have some features in common. They are all responses to perceived, unwarranted slights to some aspect of our excellence—some property of ourselves, or other people in our range of concern, that is important to us. All of these responses involve a desire to rise up against and compel another person’s will or behavior, but for somewhat different ends. Pay-back anger names a person’s desire to make a perceived offender suffer unwanted pain for the pain he previously caused her. This desire can be elaborated as a desire to impress on him that he will not be allowed to act as though he were above the norms of the group. He will follow the rules or be taken out. Protection-anger names a desire to make someone back off from us or our loved one, get out of our ‘face,’ and leave us in peace or at least feeling safe from further encroachments on our space from him. And recognition-anger names a desire to make someone acknowledge our equal human dignity or the dignity of others for whom we care. It might extend to include a desire to make someone acknowledge additional qualities that are expressions of our dignity. Note again that, in specifying these three forms, we are not implying that they are the only forms worth identifying. Rather, they should be viewed as a suggestive selection—a few points on a spectrum. This selection allows us to show that a lot of important experiences, of people in very different social contexts and positions, would be occluded or discounted if the latter two forms of anger were reduced to payback-anger.

4.2. Fluidity of Anger

Calling again on the metaphor of the color wheel, multiple blues [

Figure 2] can be distinguished for different purposes. For example, a painter might need to make fine distinctions in ordering and mixing his paints. Yet these hues are not actually singular and discrete. Blues occur along continuous spectra that spread incrementally in multiple directions at once. Similarly, although we have specified some different forms of anger, experiences of them should be viewed as porous. Each of them can easily overlap or flow into and out of another as the details of situations change. Each anger-term can be a useful construction inasmuch as it allows us to refer to something significant that happens to us, between us and others, and between other people who care about happiness and are disturbed when their path to happiness is thoughtlessly or deliberately blocked. Yet each term can mislead inasmuch as its contingency is not recognized.

When it comes to describing experiences of anger, many people’s efforts are limited not only by cultural habits, including anger-scripts, but also by biases, protective defenses, self-deception, physiological makeup, social location, and other factors. Their efforts are conditioned by the ways that they have or have not been encouraged to know themselves and to understand other people’s perspectives. Thus, a person’s self-descriptions ought not simply to be taken for granted as adequate to the experiences that they are intended to highlight. At the same time, a person’s self-descriptions ought not simply to be discounted. Our efforts in this essay are similarly limited, reflective of the experiences of people who have written about anger and spoken of it in their communities—people from whom we have learned and with whose experiences we have sought to identify through the practice of empathy. To acknowledge the contingency of our descriptions does not imply that our scholarly efforts are without merit. It only means that talking about emotions and assessing their roles in human communities is more complex than it might at first appear. One set of nomenclature, one theoretical framework, one branch of moral discourse does not fit all. But the more approaches with which one becomes familiar, the more flexible one can become in being able to home in on certain experiences and assess what is going on ‘there.’

Anger moves not only intra-emotionally (among multiple forms of anger), but also inter-emotionally (among emotions) [

Figure 3]. Anger is capable of morphing into any number of other emotions. To put it differently, sensory

appetitus flows from one form to another in response to the ways in which people register the significance of events. We noted this flow with reference to Aquinas’s general theory of emotion. Let’s consider a more concrete example here. Consider a religious leader who is made to stand trial before his national religious body for being in a life-long, monogamous same-sex marriage. He is angry, and in his anger he wants at least three things that he can identify. He wants to compel the members of the board, and the church itself, to face up to their discriminatory attitudes and behaviors—to recognize them as unjust. He wants also to compel them to ‘get off his case’ so he can be safe from their demonstrated power to harm him. And he wants to compel them to ‘see’ him as a unique person, with many excellences, rather than as a locus of disturbing sexual behavior.

Let’s say this man meets with the governing body prior to or at the trial, and its members are gradually convinced by his words, his ethical formation, his model marital love, and his exemplary ministry, that they are in the wrong. Suppose they exonerate him and turn their efforts decisively toward changing church policy. The leader’s initial hope that the board would relent, which was part of his original anger, emerges as a hope reflecting the impression that has overcome a big part of the obstacle. Or suppose instead that the man presents his best case, ethically and theologically, and he is publicly supported by other church leaders, textual scholars, and character witnesses from around the country. Yet he has the distinct impression that the members of the board are not listening—that they have already made up their minds. They appear to treat him, not as a person, but rather as a negative example and an object lesson for others. The board stays its course, recommends disciplinary action, or revokes his authority. In that case, the leader’s anger might be crushed by a stronger power that wants to force him to change, and his anger might give way to sadness or even despair. If his anger persists, the leader might instead withdraw into a cave and think obsessively about what begins to feel more and more like a humiliation carried out by heartless people. His anger might flow into hatred.

It is not only that anger can flow into neighboring emotions; neighboring emotions can also flow into anger. Suppose when the leader is called to stand trial, he is initially sad because he has no hope that the board will recommend a change in rules. But then he is visited by a friend who says “That’s just wrong. Present your case! Our religious text supports you. It is their rules that are heretical.” His sorrow, linked to hope, emerges now as anger. It is not lost on him that this anger serves as a tie that binds him to his religious community, at least for the time being.

Fischer and Roseman (

2007) determined that, for their research subjects, anger was more likely to lead to reconciliation than was hatred. Roseman comments that “This finding could be interpreted as indicating that one of the emotivational goals of anger [unlike contempt] is to maintain a relationship with the target of the emotion (e.g., de Vos et al. 2016)” (

Roseman 2018, p. 150).

It can be helpful to think of a given experience of anger as part of an emotional suite. Emotions often come bundled together, with each emotion comprising a different angle on one or more scenes or different aspects of the same situation, and each can take a turn, slipping or surging into the more dominant position in a person’s awareness. Instead of envisioning a linear flow from one form of anger to another, or to a different emotion altogether, we imagine an undulating force of

appetitus that moves irregularly, pushing and pulling in multiple directions, often at the same time. As this image suggests, there is something unstable about emotions that arise, change us, and then recede, giving way to other emotions or relative emotional calm. And yet the instability need not be regarded as a problem. Consider for a moment your skin. It appears intact and stable. Yet in reality it is always sloughing and renewing; human skin completely turns over every few weeks or months depending on a person’s age, with the healthiest, most stable skin reconstituting at an express pace. Skin is maximally stable when and because it turns over. Dry, dead, blocked surface cells are shed to accommodate more vital cells rising from deeper layers of skin. By analogy, emotional stability depends on processes of emotional change and renewal, characterized by emergence, possible prominence, death (by way of cessation), turnover, and regeneration. Much of this process simply happens to us, rather than being wrought by us. But it is something of which a mature person can become more aware. A person can practice being at ease with constant interior change in the context of constant exterior change. This being-at-ease in the unfolding of her own reality is characterized by Aquinas as a form of love (

amor) (

Aquinas 2012, I-II 27.1).

4.3. Saturation Levels of Anger

Anger is almost always informed by thought, whether that thought happens to be rational or irrational. Particular episodes of anger are preceded by thoughts about the world, one’s situation, one’s relationships, and one’s nearness to happiness. These thoughts can influence how a situation strikes a person on a sensory level. If a person repeatedly brings sound thinking to bear on emotional aspects of her experience, good habits are likely to develop, which will make it easier for her generally to get anger right, if not in the initial moment of upsurge, then in subsequent moments. Regarding the influence of rational thought and reflection, the color metaphor remains helpful.

Color saturation refers to the intensity or purity of a color. A saturation scale shows gradients [

Figure 4]. High saturation indicates the most intense form of a given hue, and low saturation or desaturation indicates a less intense form of the same hue. By analogy, a high-saturation anger might be understood as one that is relatively impulsive and opaque, and a low-saturation anger might be understood as one that is more reflective and transparent to its human subject.

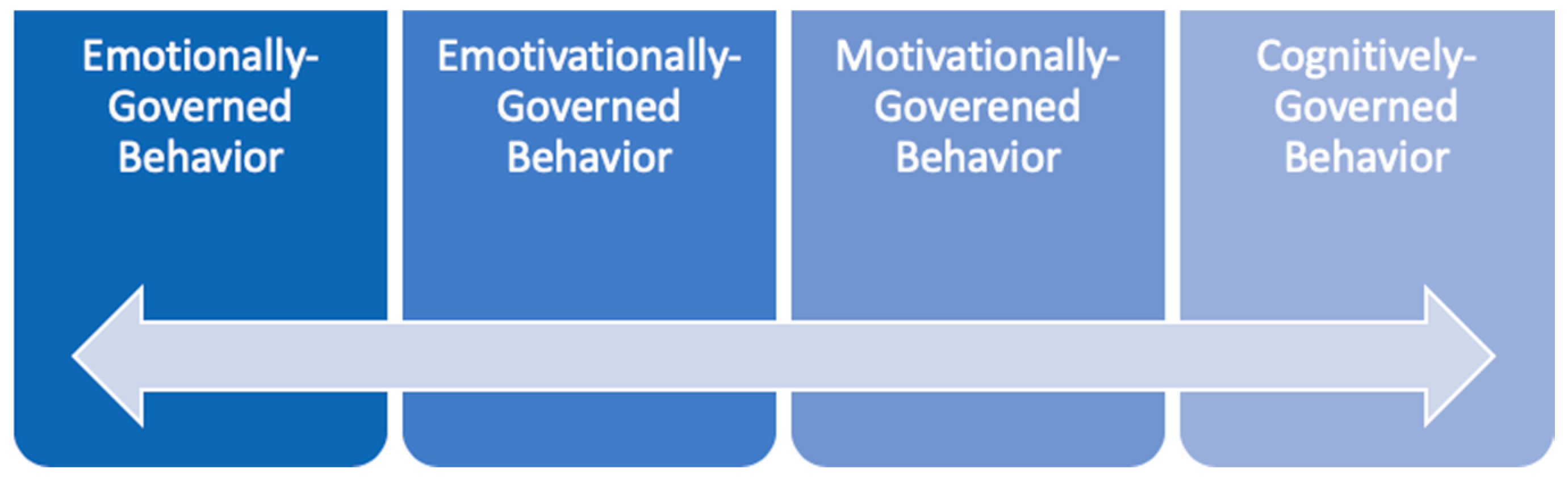

Roseman discusses how rational thought can inform

behaviors that are expressive of anger. He identifies four points of saturation on a gradient scale: emotionally-governed behavior, emotivationally-governed behavior, motivationally-governed behavior, and cognitively-governed behavior [

Figure 5]. On his view, emotionally-governed behavior “is often more impulsive, involving greater reliance on relatively pre-specified patterns of action readiness (e.g., yelling or hitting in anger, freezing or running in fear)” (

Roseman 2018, p. 156). These behavioral responses are more preset and have more instantaneous control over behavior than the rest of the spectrum. We can correlate what Roseman refers to as emotionally-governed behavior with the basic experience of anger itself—the impulse to ‘rise up against and compel.’ Further along the scale, emotivationally-governed behavior is more reasoned than emotionally-governed behavior. It is less impulsive than behavior that is governed by innate tendencies, but more impulsive than behavior that is governed by greater reflection.

17 Along the same lines, motivationally-governed behavior “is often more deliberative (though much ‘deliberation’ may occur unconsciously), as executive functions process whether particular responses will result in rewarding or aversive consequences and may compare the relative efficacy of different instrumental actions” (

Roseman 2018, p. 156). Again, we can correlate what Roseman refers to as emotivationally and motivationally governed behavior with what happens when an initial impulse becomes overlaid with thought and is conditioned by the further clarification of thought. Roseman only alludes to cognitively-governed (which he calls “non-affective”) behavior as a continuation of the spectrum. We would say that, should there come a point on this continuum where a person has lost track of the emotion she previously experienced—if her interior sensory operations give way to a predominance of intellectual activity about the same object—then she is better characterized as acting from a motion of the will, caused mainly by her own thoughts, such that her behavior is mostly the result of choice.

We are concerned in this paper, not with behavioral expressions of anger, but with anger as a form of desire, although it is fascinating to think about the ways in which an agent’s action can feed back into the way she feels. Limiting ourselves to three points on a saturation spectrum, we offer somewhat fuller descriptions of various experiences of anger. The first point could represent anger that is most basic, sensory, and immediate—only weakly informed by the self-consciousness and reflection that allow a person to grasp that she is not identical to her anger. If a person reflects on this anger at all, she perhaps has an impression that her anger is driving her.

A position midway along the continuum could represent anger that flows into and out of various levels of engagement with a person’s intellectual powers. The core impulse is emerging in one or another more determinate form, and the person is aware that she is the subject of her own anger and of much else besides. There is a limited awareness that she can make aspects of her experience objects for thought.

It is interesting to note that, on Roseman’s view, the anger-comprising goal of causing an offender pain in order to force him to change—more precisely, the behavior that expresses this desire—lies midway along his saturation spectrum. He writes, “Perhaps harm-seeking should be understood as an intermediate goal of anger—a means to making the target change behavior and deterring similar instances of harm (Fessler 2010)” (

Roseman 2018, p. 148). Roseman’s comment suggests that, as a person’s anger becomes more subject to critical thought, the person is more capable of asking herself what she really or ultimately wants in her anger, and she is better able to work with her desires in light of moral goals.

Toward the end of the spectrum, a person is much more aware of and potentially more truthful about the multiple causes and conditions of her anger. Advanced critical reflection allows a person, under certain circumstances, to become more conscious and discerning about the ways in which her anger is formed by social and cultural conventions and by other influences that comprise so much of the soup within which a human life-form comes to awareness of itself in relationship to other entities. In experiencing a relatively unsaturated form of anger, a person is likely to be aware of herself, not only as a human subject, but also as an agent who is responsible for exercising reason and self-determination with respect to her experience and toward the world within which she is nested. A person is likely to realize that she has the capacity to be a factor influencing the way her life unfolds, even as she experiences the effects of factors over which she has little or no control.

To summarize this section, we have argued that anger can come in multiple hues or shades, not all of which involve a desire to make someone suffer in just payment for committing a wrongful slight. It can be helpful to draw conceptual boundaries between some of these hues for the sake of achieving greater clarity and purchase on aspects of one’s emotional life. And yet such boundaries ought to be regarded as porous, and emotions as quite fluid. One form of anger can easily drift into another, and back again, or an agent can deliberately cause an emotional drift as a situation changes and she also changes. Anger can operate as part of a suite of emotions, the members of which engage in frequent interplay. We find it helpful to consider that all emotions are connected as forms of appetitus or tending that orient us in relation to other objects and subjects in our profoundly interconnected and interactive world. Emotion concepts can be thought of as potentially capturing a segment of experience within a sea of appetitive change, which is tied to everything else that is going on in the universe. Finally, anger can arise and persist in forms that are more or less saturated and opaque, more or less unsaturated and transparent to the subject herself.