Abstract

This study examines the multidimensionality of spirituality by comparing the applicability of two models—the five-dimensional model of religiosity by Huber that we have extended with a sixth dimension of ethics and the three-dimensional spirituality model by Bucher. This qualitative study applied a semi-structured interview guideline of spirituality to a stratified sample of N = 48 secular individuals in Switzerland. To test these two models, frequency, valence, and contingency analysis of Mayring’s qualitative content analysis were used. It could be shown that Bucher’s three-dimensional model covers only about half of the spirituality codes in the interviews; it is especially applicable for implicit and salient spiritual aspects in general, as well as for spiritual experience in specific. In contrast, the extended six-dimensional model by Huber could be applied to almost all of the spirituality-relevant codes. Therefore, in principle, the scope of this six-dimensional model can be expanded to spirituality. The results are discussed in the context of future development of a multidimensional spirituality scale that is based on Huber’s Centrality of Religiosity by extending the religiosity concept to spirituality without mutually excluding these concepts from each other.

1. Introduction

The term ‘spirituality’ and individuals’ self-description as ‘spiritual’ have found growing popularity in public discourse during the last few years, inspiring the social-scientific research of religion and religiosity accordingly. Especially in Western democratic countries, individuals increasingly detach themselves from institutional forms of religion, while continuing to call themselves spiritual (Hood et al. 2009; Houtman and Aupers 2007). In social-scientific research, this often resulted in the tendency to contrast religiosity as institutional, rigid, and negatively connoted with spirituality as individual, flexible, and positively connoted or even to a replacement of religiosity with spirituality (see Zinnbauer et al. 1997; Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). Later approaches conceptualize religiosity and spirituality as overlapping constructs without pitting the constructs against each other (Yamane 1998; Zinnbauer et al. 1997). This is especially due to the scientific result that most individuals identify themselves as “religious and spiritual” (Streib and Hood 2016). Some social scientists consider the overlap to be so large that they reject spirituality as a separate concept and continue working with the term religiosity (Streib and Hood 2011). A critical objection against this latter approach is that a growing proportion of individuals consider themselves to be ‘spiritual, but not religious’ or to be ‘more spiritual than religious’ (Carey 2018; Stausberg 2015; Tong and Yang 2018). Such a self-description can express a protest against or a rejection of a religious tradition and can, therefore, take on a rebellious nature (Chandler 2008; Hackbarth-Johnson and Rötting 2019; Hood 2003; Vincett and Woodhead 2016).

Spirituality has been a much-studied phenomenon in the field of psychology and sociology of religion over the past two decades, however it lacks conceptual, structural, and functional clarity and, for these reasons, is a rather uncomfortable subject for social scientists (Johnstone et al. 2012; Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). Thus, the conceptualization of spirituality is an open and frequently discussed question. This does not only refer to the relationship between religiosity and spirituality, but also to the inner structure of spirituality and its psychological functions. While some researchers refer to spirituality as a personality dimension (Emmons 1999; Piedmont 1999), others consider spirituality to be an intelligence dimension (King and DeCicco 2009) or a more general cognitive orientation (MacDonald 2000), and yet others conceptualize spirituality as an attitude towards purpose and meaning of life (see Koenig 2008). In recent years, emic approaches have been attracting scientific attention in the way that spirituality is defined by study participants (Altmeyer et al. 2015; Berghuijs et al. 2013; Eisenmann et al. 2016; Keller et al. 2013; Steensland et al. 2018) with inconsistent results depending on the religious-cultural background of the respondents that urge for meta-analytic studies.

From our psychological perspective, everyday lived spirituality, especially of those individuals who define themselves as non-religious or atheist, is more significant than querying subjective semantics of spirituality. Therefore, our study follows a different approach as it wants to shed light on the structure of spirituality by applying two already existing multidimensional theories of religiosity (Huber and Huber 2012) and spirituality (Bucher 2014) to in-depth interviews conducted among a sample of non-religious or atheist adults. According to the best of our knowledge, neither model has been applied to qualitative interview data yet. As our sample of non-religious individuals goes far beyond the definition of spirituality as a part of religiosity (e.g., Pargament 1999; Wulff 1997), we agree with the majority of current research that spirituality is the broader concept that can, but does not necessarily have to include religious elements (e.g., James 1902; Stifoss-Hansen 1999; see Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005).

An additional challenge in research on spirituality and its relationship to religiosity is that both can take on explicit or implicit forms (Luckmann 1967; Schnell 2009). Vincett and Woodhead (2016) outline that spirituality takes on social forms that make a spiritual lifestyle more implicit since the 2010s than ever before. They state that spirituality “becomes increasingly mainstream, […] fused with many manifestations of popular culture, and established in a range of social spheres, including healthcare and education” (p. 342). Therefore, individuals are becoming increasingly unaware of spirituality in their own lives, such as mind/body/spirit practices and underlying beliefs (e.g., alternative healing; see Chandler 2008). Consequentially, we combine an emic (explicit) and an etic (implicit) approach when defining spirituality and religiosity: If an individual refers to a religious tradition and is at the same time aware of the religious-traditional connotation, we define the utterance as explicitly religious. If the person is not aware of his/her reference to a religious tradition or denies such a reference (e.g., ‘This has nothing to do with religion’), we define the utterance as implicitly religious. Explicit spirituality is again emically defined, whereas implicit spirituality is etically defined by using Tillich’s (1957) concept of ultimate concern, which is reflected in Yinger’s (1970) functional definition of religion and in Bailey’s (2001) definition of implicit religion. In differentiation to proximate concerns that focus on our close demands and goals in life (e.g., having children, making a career), ultimate concerns include a spiritual component of self-transcendence: either towards the current status of the own self (e.g., expansion of self), towards the material world (e.g., emphasizing connectedness to humans, animals, or nature), or towards an immaterial sphere (e.g., emphasizing connectedness to a transcendent being). Working with such a broad definition of spirituality allows us to classify individuals who are religiously institutionalized as well as individuals who clearly distance themselves from religious institutions into multiple dimensions of spirituality rather than pitting religiosity and spirituality against each other (see Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). At the same time, we react to the criticism against the concept of implicit religiosity/spirituality (e.g., Pollack and Pickel 2007) by introducing the criterion of ultimate concerns that resists the tendency of implicit spirituality to bogart all life aspects as spiritual.

1.1. First Model: Huber’s Centrality of Religiosity—Applicable to Spirituality?

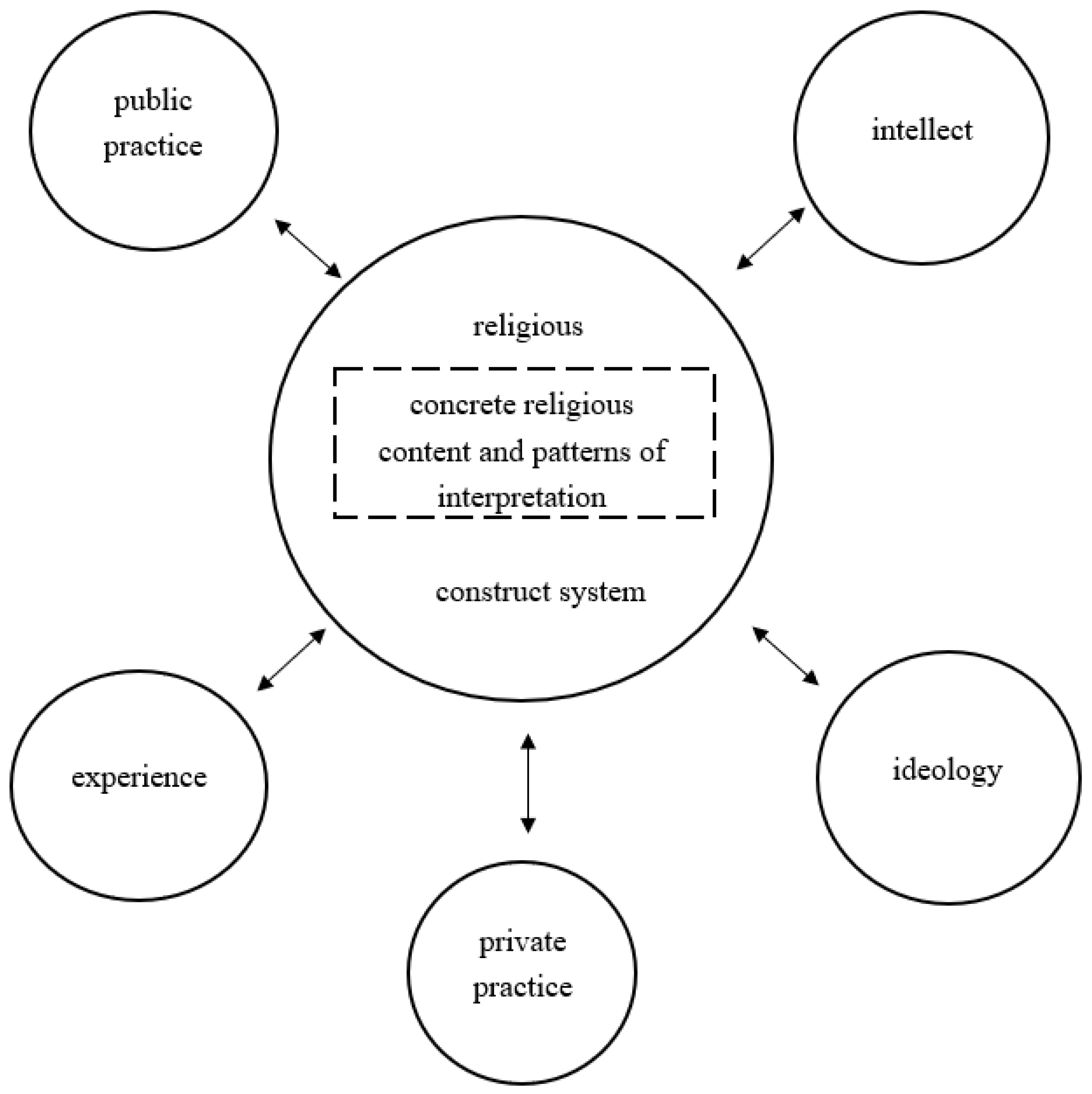

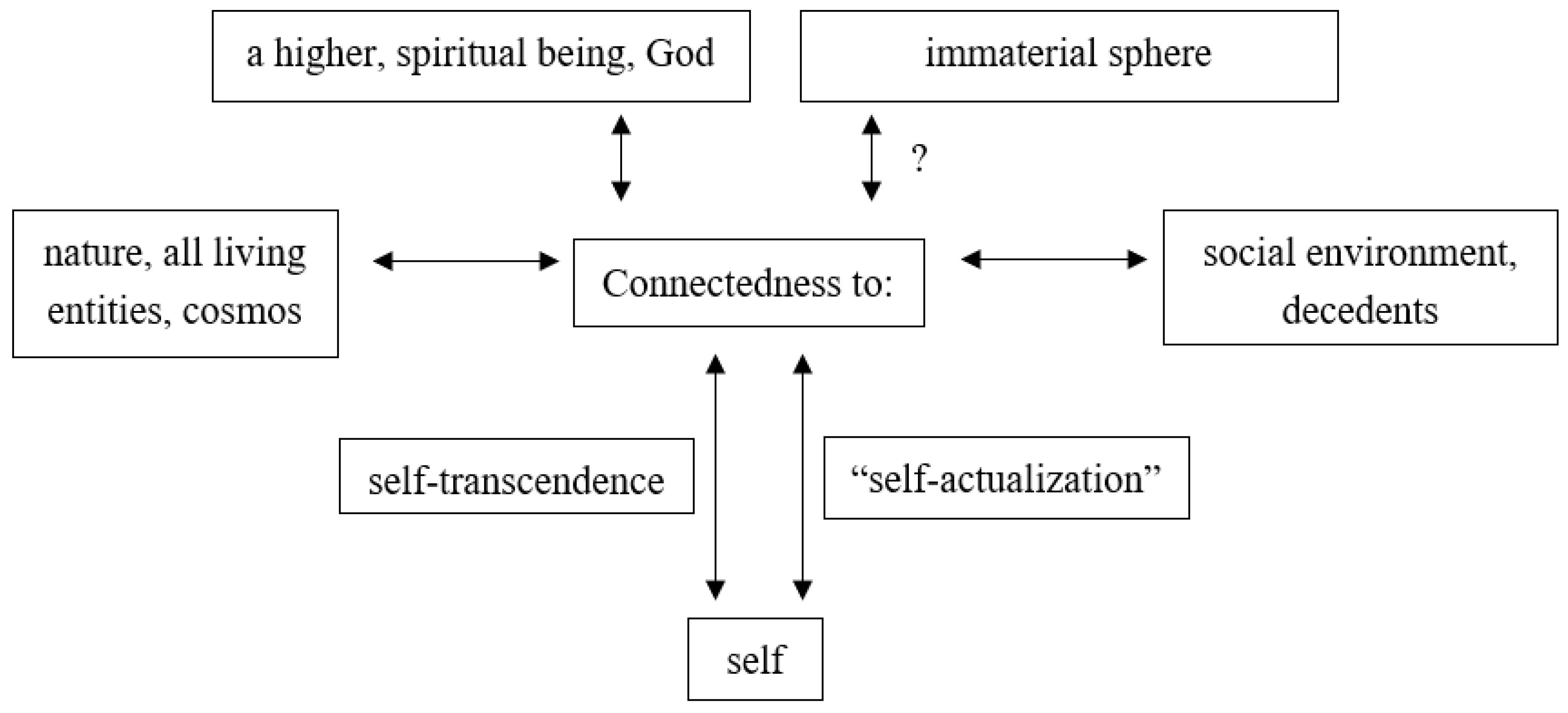

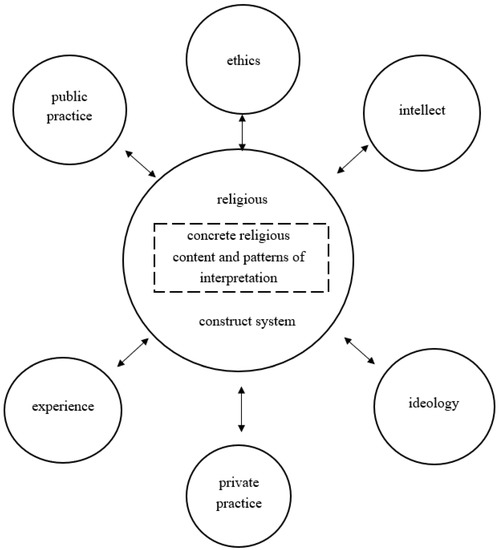

Our approach to spirituality as encompassing religiosity should be reflected in the application and a possible extension of a significant multidimensional model of religiosity to spirituality. Religiosity has been conceptualized and operationalized as a multidimensional construct in the social sciences since the 1960s (Grom 2009; Hill and Hood 1999). Following this line of research, (Huber 2003, 2009; Huber and Huber 2012) developed the model of religiosity from which the internationally accepted and worldwide used ‘Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS)’ was derived1. This interdisciplinary model combines two highly significant theories of religiosity: First, the sociological theory of Stark and Glock (1968), which distinguishes five relatively autonomous dimensions of religiosity: public practice (e.g., church service), private practice (e.g., prayer), intellect (e.g., religious knowledge), experience (e.g., feeling God’s presence), and ideology (e.g., belief in God). As stressed by Huber (2003), these dimensions simultaneously encompass the whole spectrum of psychological basic modes: cognition, beliefs, perceptions, emotions, and behaviors that might be an explanation as to why Stark and Glock proved its intercultural and interreligious validity. Secondly, Huber uses the psychological theory of intrinsic religiosity (to be religious for its own sake) and extrinsic religiosity (to be religious for social or personal comfort) by Allport and Ross (1967). In Huber’s model, the five dimensions of Stark and Glock are conceptualized according to their intrinsic importance and salience in the individual’s life (low, medium, high); the sum of this intrinsic importance of all five dimensions is called centrality of religiosity in the individual’s personality (not religious, religious, highly religious). Figure 1 summarizes Huber’s model.

Figure 1.

The model of religiosity by Huber. Based on Religiosität: Messverfahren und Studien zu Gesundheit und Lebensbewältigung (p. 88) by C. Zwingmann & H. Moosbrugger (Eds.), 2004, Münster: Waxmann. © by Waxmann.

In order to apply Huber’s approach to spirituality, we want to add the ethical/consequential dimension to this model. This dimension was part of the multidimensional model by Glock (1962). However, it was later excluded by Stark and Glock (1968) and Huber (2003). Which values and ethical beliefs people who define themselves as ‘spiritual, but not religious’ or ‘rather spiritual than religious’ consider important in their lives is controversially discussed (Chandler 2008; Comte-Sponville 2009). Some approaches regard an ethical dimension to be the center of the spirituality concept (e.g., Carey 2018; Eisenmann et al. 2016), while others locate it at the margins of it (e.g., Berghuijs et al. 2013; Steensland et al. 2018). We want to raise the question if non-religious or atheist individuals report an orientation toward values in their everyday lives that can be explicitly reported or etically defined as spiritual.

1.2. Second Model: Bucher’s Three-Dimensional Model of Spirituality

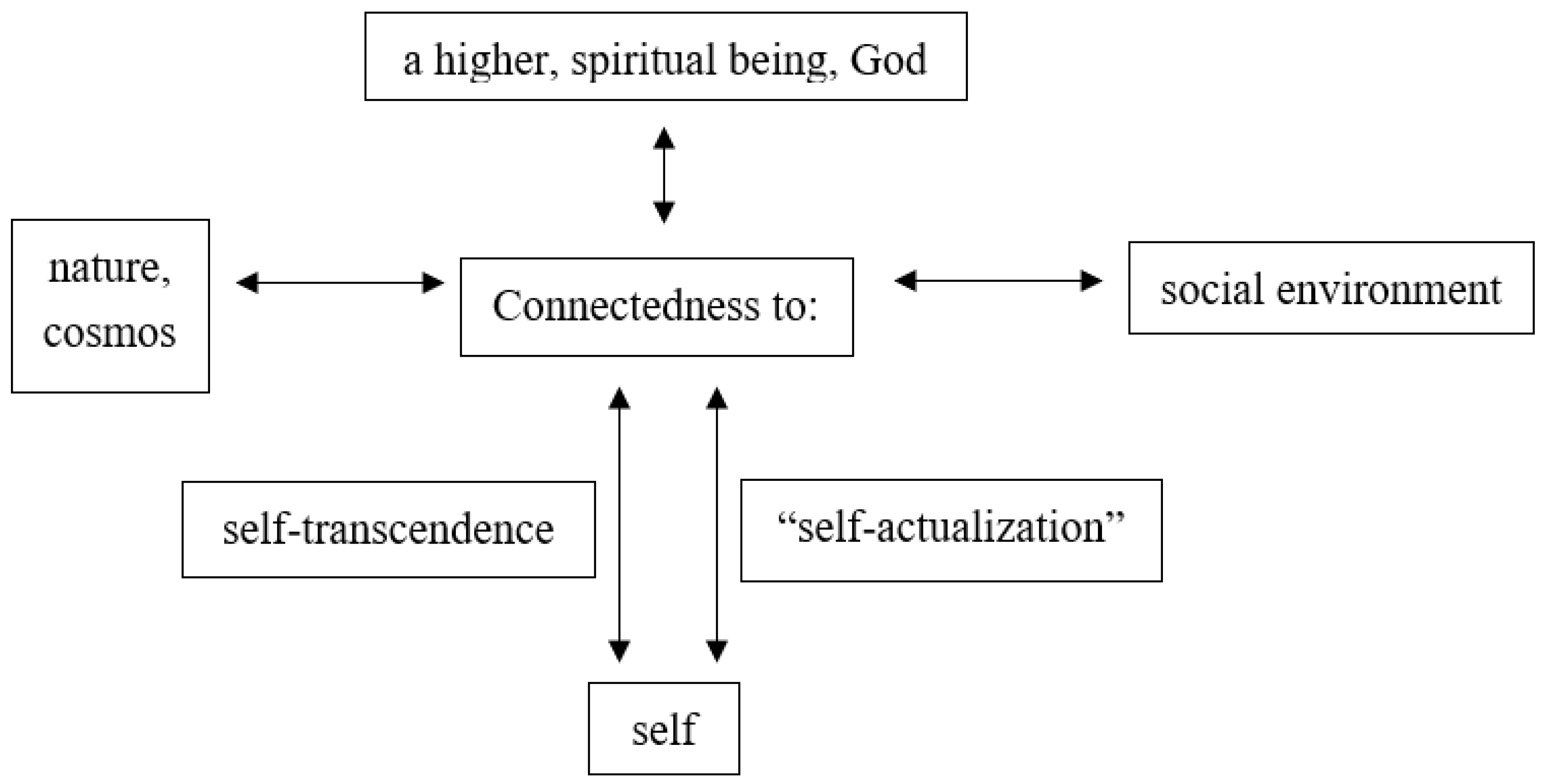

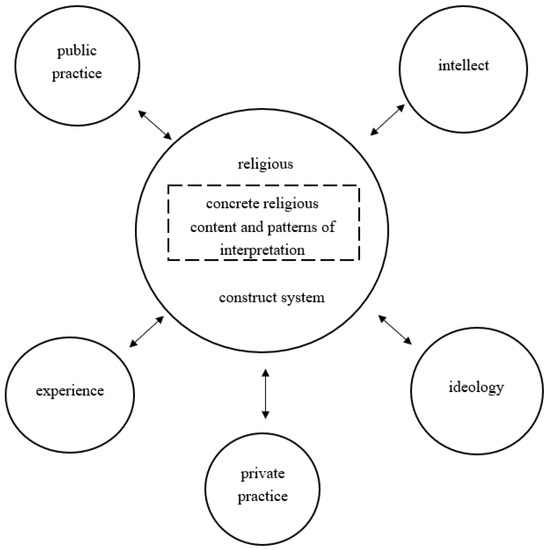

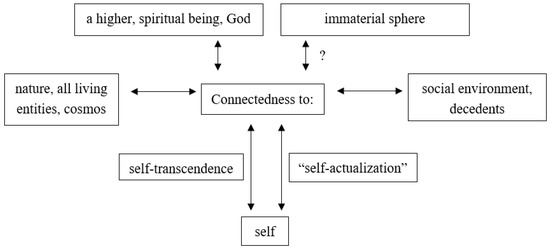

Inspired by conceptual considerations (Hill et al. 2000) and analyses of the importance of spirituality in the general population (Skrzypińska 2014), multidimensional concepts of spirituality are increasingly introduced into the discussion (e.g., Büssing 2017; Johnstone et al. 2012; Zwingmann and Klein 2012). Bucher (2014) proposed one of the most relevant multidimensional concepts of spirituality in recent years. Bucher does not only use a comprehensive range of relevant qualitative empirical results on spiritual experience to induce his model but also claims that his model is particularly adaptable to qualitative research on spirituality, wherefore it plays a central role in the present study. The core of spirituality is connectedness, which is the feeling of unity with oneself, with the immanent environment, or with a transcendent sphere. Therefore, Bucher defines three dimensions of spirituality:

- connectedness to transcendence (vertical dimension; subdimensions: to a higher spiritual being/God),

- connectedness to immanence (horizontal dimension; subdimensions: to the universe, nature, social environment, greater whole), and

- connectedness to self (depth dimension; subdimensions: connectedness to self, body).

The benefit of this broad definition of spirituality is the incorporation of more secular forms of spirituality (see Schnell 2009), i.e., the horizontal and the depth dimensions of connectedness. Therefore, Bucher does not only use the prominent two dimensions of vertical and horizontal spirituality (e.g., Piedmont 2004; Steensland et al. 2018; Streib and Hood 2016) but also adds a third depth dimension. He even defines self-transcendence as the ability of humans to go beyond themselves, which is a precondition to feel connected on a horizontal and vertical dimension, and as a result to expand and actualize the own self. Figure 2 summarizes Bucher’s model.

Figure 2.

The model of spirituality as connectedness by Bucher. Based on Spiritualität (p. 40) by A. Bucher, 2014, Weinheim: Beltz. © by Beltz.

2. Study Aims

The present study aims at further clarification of the multidimensional construct of spirituality by applying two established models of religiosity and spirituality to qualitative interview data: the model of religiosity by Huber (2003); (Huber and Huber 2012) and the model of spirituality by Bucher (2014). Moreover, we ask if Huber’s and Bucher’s multidimensional models should be extended by adding additional (sub-)dimensions by induction from the empirical data.

Specifically, the research questions for the extended model by Huber are the following:

- Do the six dimensions of religiosity—public and private practice, intellect, experience, ethics, and ideology—cover the utterances and the personal significance of spirituality in individuals’ lives?

- Can these six dimensions of religiosity and/or their subdimensions be extended by inductions from the empirical material?Analogously, we raise the following research questions regarding Bucher’s model:

- Do the three dimensions of spirituality by Bucher—vertical, horizontal, and depth dimension—cover the utterances and the personal significance of spirituality in individuals’ lives?

- Can these three dimensions of spirituality and/or their subdimensions be extended by inductions from the empirical material?

Beyond the criteria to test the applicability of both models to spirituality in its life-related aspects, the criterion of parsimony is of importance, in which Bucher’s model has the upper hand, as it is the less complex model with only three instead of six dimensions.

3. Method

3.1. Procedure and Sample

With specific attention to the findings that spirituality is becoming increasingly implicit (Luckmann 1967; Schnell 2009; Vincett and Woodhead 2016) we want to focus on a sample of seculars—i.e., individuals who consider themselves non-religious or atheists—and apply an interview to them that asks about spirituality directly or indirectly. The here presented data is a part of the mixed-method research project on seculars in Switzerland2. It uses the quantitative data of the Religion Monitor from 2013, which was collected among a representative sample (N = 1003) that represents all three language areas of Switzerland (German, French, Italian). During the applied telephone interview in November and December 2012 using a standardized questionnaire on religiosity (Pickel 2013), n = 341 participants define themselves as nonreligious or atheist and were categorized as ‘seculars’—nevertheless, they can be religiously affiliated or unaffiliated. Among them, n = 113 agreed to an additional face-to-face interview and from those a stratified sample according to age, gender, language, and religious affiliation of n = 83 participants was randomly drawn.

The current study is based on the German-speaking subsample (n = 48). Thereby, we simplified the analyses by keeping the variables of language and culture constant. The following socio-demographic and socio-religious data of our subsample is derived from the earlier questionnaire study. The age of the sample ranges from 18 to 83 years old (M = 51.46, SD = 14.32), a majority of 72.9% are male. Regarding marital status, half of the sample reports to be married or to live with a partner, 20.8% do not, while the rest left the question unanswered. Our sample is highly educated: 64.6% have a university or college degree, 12.5% have an A-level, and only 22.9% hold a secondary or upper secondary education as their highest qualification. Moreover, the self-assessed economic situation is above the scale average (scale ranges from 1–4, higher scores indicate higher economic status) with M = 3.19 (SD = 0.53). Regarding socio-religious variables, a majority of 52.1% report that they are religiously non-affiliated. 43.8% were religiously socialized during their childhood, 31.3% report that they were at least partly religiously socialized, and the rest was non-religiously socialized. In summary: our sample reflects a typical European ‘secular’ sample as it is predominantly male, highly educated, and of high economic status (Keller et al. 2013). Additionally, on average the sample scores higher on spirituality (M = 2.13, SD = 1.20) than on religiosity (M = 1.63, SD = 0.96; both answer scales range from 1–5) and can consequentially be labeled as ‘more spiritual than religious’.

A semi-structured interview guideline was applied to this sample by trained interviewers that asked about the following aspects related to three main topics of the interviews:

- religiosity (religious socialization; religious education of own children; exchange of religious ideas with others/partner; Is there anything religious in your life? What do you think about prayer? Do you make use of religious offers?);

- spirituality (Is there anything spiritual in your life? What do you think about meditation?; Do you feel connected to a greater whole? alternative healing); and

- meaning of life (Do you find meaning in your life? Did you ever experience a meaning crisis? Have you experienced any significant life changes during the last five years?).

These in-depth interviews lasted between 28 and 233 min (average: 77 min).

3.2. Data Analysis

According to Barton and Lazarsfeld (1979), the main aim of qualitative research is a classification or dimensioning of empirical material related to a certain phenomenon. As our goal is to examine multidimensional approaches of spirituality, we apply Mayring’s (2014) qualitative content analysis to the transcribed interviews with the support of MAXQDA software. Content analysis is defined as a systematic (i.e., according to explicit rules), theory-based analysis of fixed communication material that is able to reveal not only manifest but also latent semantics. A system of categories is central for qualitative content analysis that assigns categories to text passages in an interpretative way. Therefore, categories must be precisely defined, transformed into coding rules, explained by anchor examples, and differentiated from similar categories. These categories are deduced from one or several theoretical models, which guide the research questions and the analysis, but the whole procedure allows explicitly inductive category formations. This is of significance since a qualitative-inductive approach is appreciated as an outstanding opportunity for research on conceptualization of spirituality (Hood et al. 2009; Miller and Worthington 2013; Streib and Hood 2011). Mayring defines three sub-techniques of qualitative content analysis:

- frequency analysis (“to count certain elements in the material and compare them in their frequency with the occurrence of other elements”, (Mayring 2014, p. 22));

- valence analysis (“procedures which accord a value to certain textual components on an assessment scale of two or more gradations”, ibid., p. 26); and

- contingency analysis (to examine whether particular categories occur with particular frequency in the same context with the target to “extract from the material a structure of text elements associated with one another”, ibid., p. 27).

In our study, the model of religiosity by Huber (Huber and Huber 2012) and the model of spirituality by Bucher (2014) are the theoretical foundation from which the analytical categories are deduced. Moreover, our research aims ask for the extension of the models, which allows for the induction of additional dimensions that might not be covered by the models yet.

Every meaningful proposition in the interviews that meets our previously introduced definition of explicit and implicit spirituality and religiosity is coded in a four-step process:

- A code of one of the six dimensions by Huber is applied; if not applicable, a new dimension should be formed; the numbers of the given codes are counted and compared with each other (frequency analysis);

- Every code derived from Huber is given a code of the individual importance/salience (not important–ambivalent–important: valence analysis, related to the six dimensions: contingency analysis);

- A code of one of the three dimensions by Bucher is applied; if not applicable, a new dimension should be formed; the numbers of the given codes are counted and compared with each other (frequency analysis);

- In order to compare both tested models, we examine whether dimensions of Huber and the dimensions of Bucher are contingent—i.e., whether they are connected with each other (contingency analysis).

The definitions of our deduced categories of analysis, including coding rules and anchor examples, are displayed in the comprehensive coding guideline in Appendix A.

Every step of the coding procedure (for an overview of the step-by-step model see (Mayring 2014, p. 61)) was discussed in an interdisciplinary research team consisting of psychologists and sociologists of religion, religious scholars, and theologians. These team discussions of text parts and whole cases concluded after each round with (preliminary) category definitions, rules of differentiation to similar categories, and anchor examples. This intersubjective approach did not only solve discrepancies of categorization but also incorporated definitions of categories and related coding rules that were induced from the empirical material into the coding guideline. After a first trial whereby 10 cases were encoded, the coding guidelines were revised for the first time, applied again to the previously coded cases and new cases, and whenever necessary, revised by the researcher team again. During the whole coding procedure, we went through this back-and-forth process four times. The induced categories, called generic codes, can be also found in Appendix A.

4. Results

4.1. Testing Huber’s Model: Frequency Analysis

All K = 1625 given codes of implicit or explicit spirituality and religiosity were completely absorbed by the six dimensions by Huber (2003). Except for religious experience, subdimensions were formed within every dimension, which are displayed with their frequencies in Table 1.

Table 1.

Of the frequency analysis of dimensions and subdimensions of spirituality according to Huber’s model (K = 1625).

The dimension of ‘public practices’ (covering 11.69% of the total codes) includes rites of passage, religious service, holiday celebrations, and public meditation. The rest category ‘others’ contains all public practices that were reported less than 5% within the public practice dimension (those were occult/esoteric practices, art, donating, pilgrimage, prayer, exorcism, confession, alternative healing, blessing rituals).

Similarly, ‘private practices’ (covering 9.60% of the total codes) can most often be observed in prayer, meditation, and alternative healing practices. Private practices under the 5% cut-off value within this dimension were grouped into ‘others’ (consisting of wishing, mourning rituals, spiritual care, visiting energy places, occult/esoteric practices, art, mandala painting, make the cross sign, lighting a candle, actions in nature, mind-spirit training, everyday rituals).

The dimension ‘intellect’ reflects almost one-fifth of the given codes and its subdimensions primarily cover specific information channels of spirituality (e.g., discussions, books/TV, formal education), but also unspecific general interest in religion(s). Additionally, three subdimensions could be uncovered that represent central cognitive challenges with a spiritual connotation, i.e., questioning the meaning of life (without a definite answer), theodicy (the question of why there is evil in the world), and reflexivity (reasoning about own spiritual convictions with regard to their plausibility and logical consistency, see (Huber 2009)). The subdimension ‘others’ reflects the codes that were reported less than 5% within the intellectual dimension, which were public debates and questioning of alternative healing practices (regardless of their practice).

The dimension of spiritual ‘experience’ covers about 8% of the total codes and was not divided into subdimensions as such experiences are independent of their post-hoc interpretations since they share an identical structure (Hood 2003).

In the ‘ethical dimension’, which consists of the smallest share of total codes with 4.92%, the four most frequently reported subdimensions were ‘love your neighbor’, tolerance/sympathy, sustainability towards nature, and truthfulness/honesty. Other ethics cover less than 5% of the codes within this dimension and were grouped into the subdimension ‘others’ (consisting of thankfulness, altruism, justice, responsibility, loyalty/trust).

The most comprehensive dimension is ‘ideology’, covering almost half of the given codes. It consists of 19 subdimensions, which reflect attitudes and beliefs related to

- all other five dimensions (belief in private practice such as meditation; belief in public practice such as religious service; attitude towards intellectual approaches such as formal education; attitude towards ethics; the desire for experience, see Appendix A);

- all big world religions (Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, religions in general);

- central topoi (meaning of life, life after death, destiny, higher spiritual being, human being/teleology, society, natural environment, religioid ideologies such as esotericism).

In Table 1, the most commonly reported ideology subdimensions are displayed, while the subdimensions that were reported less than 5% in this dimension are summarized in the subdimension ‘others’.

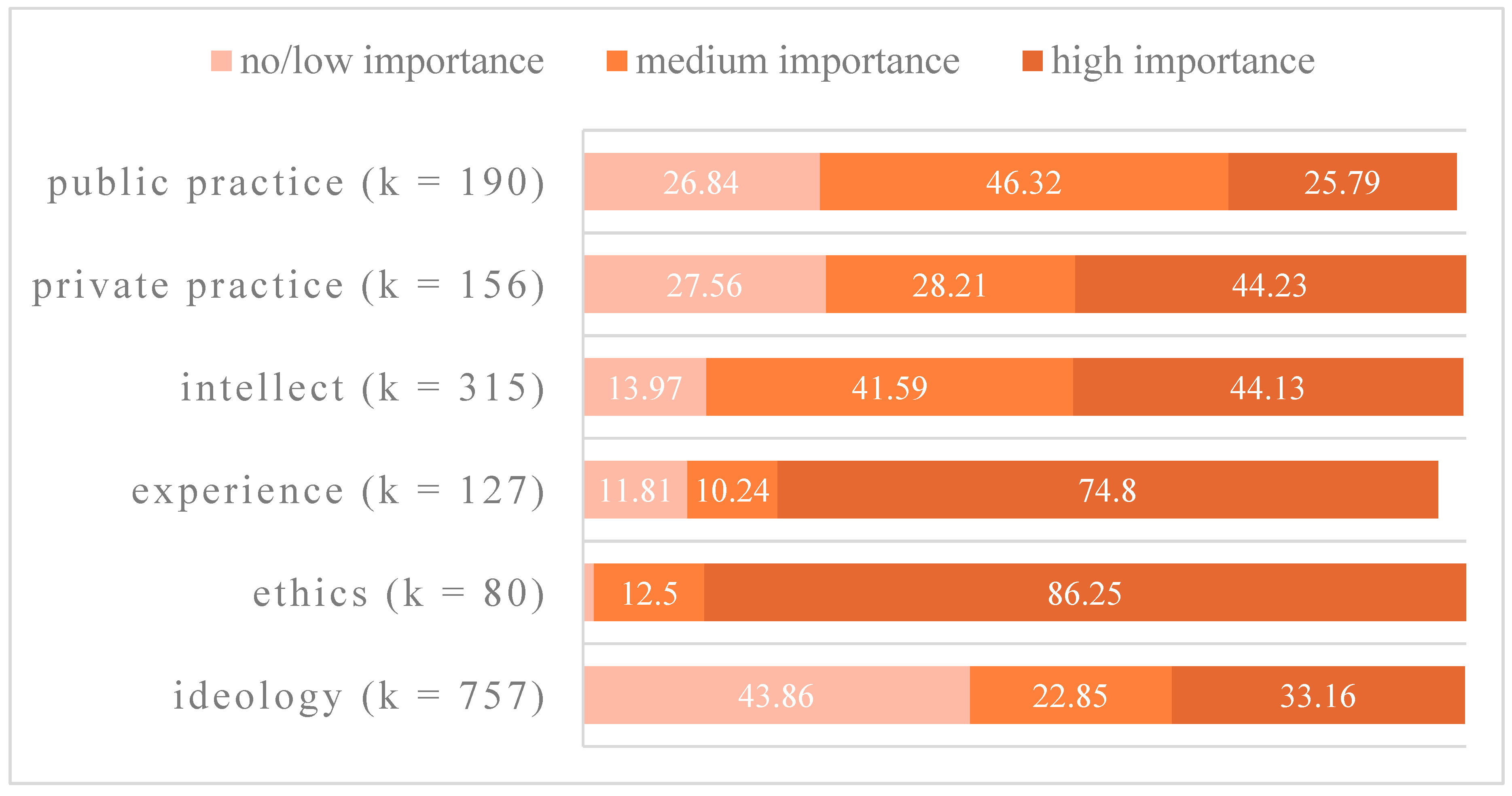

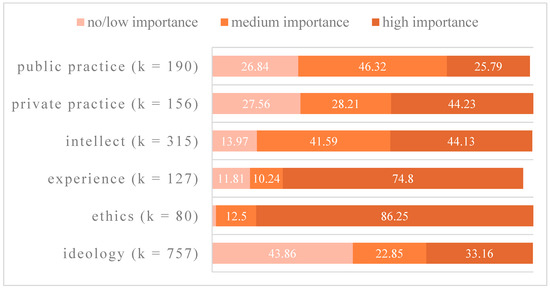

4.2. Testing Huber’s Model: Valence and Contingency Analysis

After this frequency analysis, the text propositions on spirituality were coded a second time in a valence analysis according to their individual importance/salience according to Huber and Huber (2012). Only four text propositions (0.25%) could not be coded as no/low, medium, or high importance according to the coding guideline (Appendix A), which was due to missing information in the interview data regarding the participant’s individual motivation, importance, or evaluation (e.g., “I am baptized”; “he told us something about their religious celebrations”).

Figure 3 represents the results of this analysis that tests whether the dimensions of spirituality of the first frequency analysis are contingent with the individual importance of the single dimensions. While participants report relatively high importance when they address ‘ethics’ (86.25%) and ‘experience’ (74.80%), the dimensions of ‘private practice‘ and ‘intellect’ are still evaluated as important but with a higher share of medium importance (28.21% and 41.59%, respectively). While the weight shifts to medium importance in the ‘public practice’ dimension (46.32%), the evaluations of not/low important are highest in the ‘ideology’ dimension (43.86%). Although the ideology dimension is reported with the highest quantity in the earlier frequency analysis, it is of relatively low importance for the participants. On the contrary, experience and especially ethics, which covered the lowest share of codes in the frequency analysis, show the highest importance rates.

Figure 3.

Results of the contingency analysis, displaying relative frequencies of the three levels of importance to the dimensions. Note. Public practice k = 2 n.a., intellect k = 1 n.a., ideology k = 1 n.a. Ethics are reported with a no/low importance in only 1.25% of the codes.

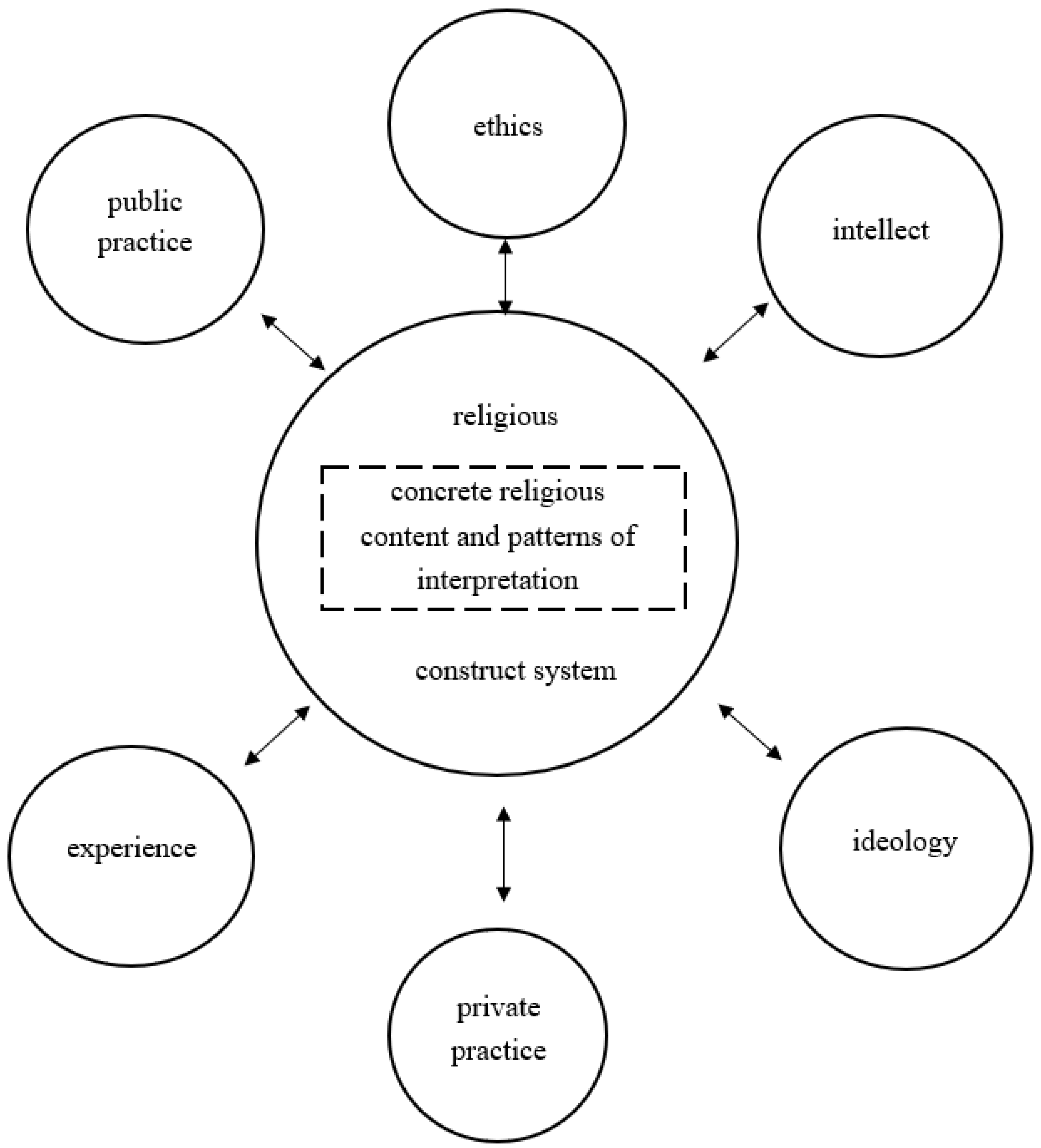

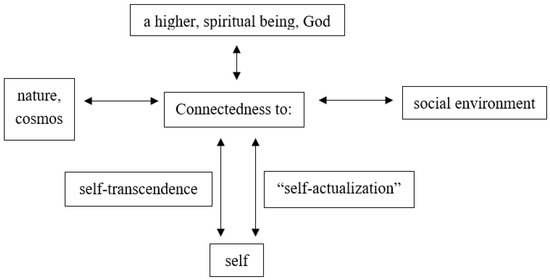

The extension of Huber’s model of religiosity to spirituality by adding the sixth dimension of spiritual ethics is displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The extended model of religiosity by Huber. Based on Religiosität: Messverfahren und Studien zu Gesundheit und Lebensbewältigung (p. 88) by C. Zwingmann & H. Moosbrugger (Eds.), 2004, Münster: Waxmann. © by Waxmann.

4.3. Testing Bucher’s Model: Frequency and Contingency Analysis

Table 2 represents the results of the frequency analysis of the dimensions and subdimensions of spirituality according to Bucher’s (2014) model. Although we added three subdimensions by inductive category building (Mayring 2014; see Appendix A), which are connectedness to an immaterial sphere (preliminarily categorized to vertical connectedness), to all living entities, and to decedents (both categorized to horizontal connectedness), the full model could only cover 48% of the codes (K = 1625).

Table 2.

Of the frequency analysis of dimensions and subdimensions of spirituality according to Bucher’s model (K = 1625).

‘Vertical connectedness’ makes up the greatest share with more than half of the connectedness codes, including connectedness to a higher spiritual being/God as the most often mentioned subdimension of connectedness. ‘Horizontal connectedness’ makes up a share of one-third of the connectedness codes, while the ‘depth dimension of connectedness’ shows the smallest frequency with only about 14% of the connectedness codes. The extension of Bucher’s model of spirituality by adding three subdimensions is displayed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The extended model of spirituality as connectedness by Bucher. Based on Spiritualität (p. 40) by A. Bucher, 2014, Weinheim: Beltz. © by Beltz.

As Bucher’s model can only capture half of the spirituality codes that were given to our previously introduced definition of explicit and implicit spirituality (including religiosity), we ask in a last step, whether Bucher’s dimensions are contingent to some of Huber’s dimensions and contingent to spiritual/religious codes as well as implicit/explicit codes. Table 3 shows the results of this contingency analysis. The central column of this symmetric table displays the number of all given codes. While the left part summarized the absolute number of the given codes related to Huber’s model as well as the implicit/explicit religious/spiritual codes, the right side of Table 3 displays the number of given codes to Bucher’s model related to the codes on the left side. The right side of the table is the focus of this contingency analysis and we start to explain it from rear to front. The last column shows that ‘public practice’ (22.63%), ‘intellect’ (23.49%), and ‘ideology’ (48.22%) are reflected in less than 49% of Bucher’s three dimensions. When we have a look at the second column from the front, public practice, intellect, and ideology are at the same time the three dimensions that are strongly affiliated with religious traditions by the participants.

Table 3.

Contingency analysis of Bucher’s model and Huber’s model.

The other three dimensions—private practice, experience, and ethics—are not as strongly linked to religious traditions by the participants and are reflected by Bucher’s model in more than 60% of the codes (last column). Interestingly, the experiential dimension is almost completely covered by Bucher’s connectedness dimensions. This tendency of the connectedness model to reflect spirituality codes better than religiosity codes is supported by the second last column that displays that the codes covered by Bucher’s model encompass more than 84% of the spirituality codes. The same tendency accelerates when it comes to implicit spirituality (see the third last column): all these codes are covered by Bucher’s three dimensions. There is however one minor exception (private practice–religious–explicit, 81.01%). The fourth-last column consistently shows that Bucher’s model is more applicable the higher the individual importance is—it does not catch rejecting answers by the participants as well as Huber’s model.

5. Discussion

The current study was conducted with the aim to examine the multidimensionality of spirituality by comparing the applicability of two different models of religiosity and spirituality—the model by Huber (2003); (Huber and Huber 2012) and the model by Bucher (2014)—to comprehensive qualitative interview data. According to significant researchers in that field, qualitative methods are the method of choice when it comes to examining multidimensionality (Barton and Lazarsfeld 1979), especially of spirituality (e.g., Hood et al. 2009; Miller and Worthington 2013). In our study, the used semi-structured interview guideline strongly focused on spirituality and was applied to a stratified sample of N = 48 secular individuals in Switzerland. In order to test the two models, frequency, valence, and contingency analysis of Mayring’s (2014) qualitative content analysis were conducted. Besides the criterion of applicability, the criterion of parsimony was also taken into account, in which the three-dimensional model by Bucher has an advantage compared to the six-dimensional approach of Huber.

Despite the criterion of parsimony, Bucher’s three-dimensional model of spirituality covers only around half of the given codes in our study, whereas Huber’s model extended with the ethical dimension covers almost all given codes: the six dimensions reflect the given codes completely, the individual importance is a 99.75% match with the given codes. The results of four text propositions, which do not show any personal valence at all, reflect a methodological problem of data collection (the interviewer failed to ask the participants about the evaluation of spiritual aspects) and not a drawback of Huber’s model itself.

Interestingly, within the multidimensionality of spirituality Huber’s dimensions ideology and intellect are in the foreground, which can be interpreted as a strong cognitive weight of the concept of spirituality (Koenig 2008; MacDonald 2000). On the contrary, this could also reflect a methodological shortcoming as interviews trigger mainly cognitively and less behaviorally or emotionally-laden utterances by the participants. Whether spirituality is mainly located on the cognitive level should be proven in a future questionnaire or experimental studies. Thereto related, ideology was evaluated as the least important among all dimensions by our secular sample. On the other hand, ethics, which was the least frequently reported dimension, was simultaneously the dimension of the highest individual importance. This result of a low frequency and high importance at the same time could clarify prevailing contradicting views on spiritual ethics (Carey 2018; Chandler 2008; Eisenmann et al. 2016 versus Berghuijs et al. 2013; Steensland et al. 2018). Consequently, the concurrent consideration of frequency and importance, which lies at the heart of Huber’s Centrality concept and scale, is of significant interest to spirituality research.

Bucher’s model had to be extended during inductive coding: the subdimensions of immaterial sphere (preliminary vertical), all living entities, and decedents (both horizontal) were not well captured by the initial subdimensions that Bucher suggested (see Figure 5). Regarding the connection to an immanent sphere, which includes “the imagination of a world ‘behind’” (Streib and Hood 2016, p. 12), e.g., paranormal or esoteric aspects, and alternative healing, its preliminary location on the vertical level remains questionable. Besides the more traditional utterances about the afterlife or spiritual helpers such as saints that point to a vertical connection, many participants reported a parallel dimension (e.g., residence for the dead, ghosts, angels), energies that are located in this world (e.g., healing), or experiences of synchronicity, which could be located on a horizontal level, too. Therefore, more research is necessary related to this newly formed subdimension of connectedness to a transempirical sphere, especially nowadays as mind-body-practices, which are a significant part of this form of connectedness are becoming more and more mainstream (Chandler 2008; Vincett and Woodhead 2016).

A remarkable result here is, that within Bucher’s model the highest emphasize is on vertical connectedness, especially to a higher spiritual being/God, and on horizontal connectedness, especially to others. Hence, our data rebuts the claim that spirituality is highly focused on the self or even an egocentric form of religiosity (e.g., Hackbarth-Johnson and Rötting 2019; see Carey 2018; Chandler 2008) but rather reflects a feeling of being connected to a divine being and fellow humans. This is supported by results from earlier studies that found that a vertical connection to a higher spiritual being remains important within the spirituality concept (Piedmont 2004; Steensland et al. 2018).

The results of the last contingency analysis that tries to relate both models with each other, revealed that Bucher’s approach is especially applicable to spirituality codes that do not refer to a religious tradition. This reflects that Bucher’s model latently follows the hypothesis that religion and spirituality exclude each other, which should be avoided according to later inclusive approaches (see Yamane 1998; Zinnbauer et al. 1997; Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). Moreover, Bucher’s model covers the experience dimension almost completely, which is at the same time the dimension on which Bucher heavily relied when conceptualizing his model. Surprisingly, implicit spirituality is completely reflected by Bucher’s model. This finding strongly supports our initial definition of implicit spirituality by using Tillich’s (1957) concept of ultimate concern (see Yinger 1970; Bailey 2001). Additionally, it shows that this three-dimensional approach of connectedness could become important in future studies, which take up highly topical research desiderata when focusing on implicit forms of spirituality (Vincett and Woodhead 2016). Finally, Bucher’s approach is more applicable the higher the individual importance/salience of a dimension is, i.e., the model of connectedness is not very applicable to negative replies by participants, in contrast to Huber’s model.

In conclusion, the results support that Huber’s (2003); (Huber and Huber 2012) multidimensional model of religiosity can be used to examine spirituality as well, which supports the approach of spirituality including religiosity (Stifoss-Hansen 1999; see Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005). The results of the present study can give a conceptual direction of spirituality (and can therefore shed light on the ongoing conceptual considerations, e.g., Hill et al. 2000; Johnstone et al. 2012; Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005), which can also lay the foundation for the construction of a multidimensional spirituality scale. Building upon our empirical results, we suggest the development of a ‘Centrality of Religiosity and Spirituality Scale (CRSS)’ for future studies. This could be possible by enriching the CRS with some new items.

In a further step, the here-presented variable-centered approach should be supplemented by a person-centered approach, which examines the stability of the dimensions of spirituality among a secular sample in a longitudinal design. Currently, the remaining participants of our sample are being re-interviewed with a similar interview guideline. A comprehensive analysis of this data is going to take place in 2020. The question for long-term effects of different dimensions of spirituality among secular individuals who report spirituality as relevant in their lives is highly disputed (Pollack and Rosta 2017) and it would be interesting to test the hypothesis that this is only a “step on the path between religion and non-religion” (Marshall and Olson 2018, p. 503).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; Data curation, S.D.; Formal analysis, S.D.; Funding acquisition, S.D. and S.H.; Investigation, S.D.; Methodology, S.D.; Project administration, S.H.; Software, S.H.; Supervision, S.H.; Visualization, S.D.; Writing—original draft, S.D.; Writing—review & editing, S.D. and S.H.

Funding

We thank Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) for funding this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Coding guideline: Deduced categories of analysis, definitions, and anchor examples.

Table A1.

Coding guideline: Deduced categories of analysis, definitions, and anchor examples.

| Category | Definition/Coding Rule Is Coded When the Participant Expresses… | Anchor Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions of religiosity * | ||

| Public practice | a religious/spiritual practice in public space (observable from outside). Is not coded if the practice takes place with or without others in private (then: private practice): Is not coded when person reports attitude towards a public practice (then: ideology). If participant also reports a religious/spiritual experience, then experience is coded, too. | “every day we had these spiritual sessions with lying down and visualizing in another world, focusing on kidney functions, listening to heart sounds”; “in common prayers: It makes me very quickly very uncomfortable” |

| Private practice | a religious/spiritual practice in private space (not observable from outside). Is not coded if the practice takes place with or without others in public (then: public practice); is not coded when person reports attitude towards a private practice (then: ideology). If participant also reports a religious/spiritual experience, then experience is coded, too. | “well, daily prayer or something like that is unnatural to me now, what I would not do it now on my own”; “That I do that, say, with mindfulness. That is a certain kind of meditation” |

| Intellect | processes or results of intellectual activities that are related to religion/spirituality. It is not coded when the belief in these results is emphasized (then: ideology). Is not coded if participant reports an attitude towards an intellectual approach (then: ideology). | “Then the Jehovah’s Witnesses come by regularly. I always discuss with them a bit”; “I read esoteric books”; “Churches were for me the most beautiful monuments in a city. That’s why I like to go in there. You visit churches, that’s part of the cultural program” |

| Experience | a religious/spiritual experience. Is not coded when participants desires such an experience (then: ideology). | “That was probably the moment when I stayed on the brakes. And then a bearded African came out of the bush […] and said ‘God has saved you’”; “I actually experience deep meaning in crises. Something is happening there, where you can go beyond” |

| Ethics | religious/spiritual values that are important in his/her life. Is not coded when participants report an attitude towards a value (then: ideology). | “I think I can love my neighbor even if I’m not religious. I will not take that away from me”; “With a lot of respect for the animals […] They apologize to every animal they kill, and treat them with love. […] I just buy meat from a good livestock farm” |

| Ideology | an attitude towards, (un)belief in, or pattern of plausibility related to a religious/spiritual issue. | “I think there’s something higher that people have grasped”; “And that’s why I believe that religion is a big problem. And I am hostile to religion”; “as soon as I scratch something, something happens. Action reaction. And that is not for nothing, that does not come out of nothing. That somehow needs a reason” |

| Importance * | ||

| no/low | that the previously reported dimension is not important/salient to the individual, and/or is rejected by the participant, and/or participant was forced to it. | “Because it’s just very attached to Buddhism and then that didn’t fit to me again”; “We had the death of my mother. I do not think she is in heaven now”; “No, it was never prayed. Nothing like that” |

| medium | that the previously reported dimension is of medium or ambivalent important/salience, and/or is extrinsically motivated; and/or does not trigger behavior outside the religious/spiritual frame, and/or was important in the past but is currently not important anymore. | “It’s just these things where you go when someone invites you. But I do not do it on my own.”; “I have been to India twice and maybe you meet a special person who somehow sets you in motion. And you think, yes, somehow. It’s probably not black and white”; “We got married in the church. Simply because it is so customary” |

| high | that the previously reported dimension is highly important/salient to the individual, and/or is intrinsically motivated; and/or triggers behavior outside the religious/spiritual frame. | “We’re actually talking about religion a lot”; “After all, meditation would be that you are actually careful in everyday life”; “That’s also what I’m interested in and that’s where my projects are” |

| Dimensions of spirituality ** | ||

| Vertical connectedness | ||

| to higher spiritual being/God | that the previously reported dimension is connected to God, the divine, or another higher spiritual being. | “I have handed it over, given to the Lord God, prayed about it, and now I can still enjoy every day”; “I say there must be a higher force somewhere, but for me that is not a cloud with the old man with a white beard” |

| to immaterial sphere (generic) | that the previously reported dimension is connected to an immanent sphere, such as the afterlife, saints, transempirical relations (paranormal, esoteric, alternative healing); is not coded when a higher spiritual being is emphasized (then: connectedness to higher spiritual being) | “So when it comes to pendulum dowsing it’s just that way, you have to have a question. […] And the pendulum then gives me the answer”; “I also made a lot of laying on of hands with me”; “I look at the calendar, then it was exactly two years after this event. And there I was shocked. That’s when I started shaking” |

| Horizontal connectedness | ||

| to universe | that the previously reported dimension is connected to the universe or outer space; is not coded, when nature in general is emphasized (then: connectedness to nature). | “When I’m in the dark […] and see the stars, you get into such a state. […] That’s my spirituality”; “it’s not enough for me to just sense and recognize my connection and interconnectedness with the universe if I do not become active in it” |

| to nature | that the previously reported dimension is connected to nature: Is not coded, when universe is emphasized (then: connectedness to universe); is not coded, when living entities in general are emphasized (then: connectedness to all living beings). | “nature most likely. I am very fond of nature. That’s a bit of my spirituality”; “Then you can have that feeling too. In great nature. In that sense you can say that it is a spiritual experience”; “a morning walk, in the morning at six in a snowy forest, then suddenly the sun comes through the branches, then that’s another moment, which I call spiritual” |

| to other humans | that the previously reported dimension is connected to fellow human beings that is beyond utilitarianism (e.g., trust, love your neighbor, responsibility, against social conventions, define own identity via other humans, give meaning of life). Is not coded, when nature in general is emphasized (then: connectedness to nature); is not coded when it is connected to decedents (then: connectedness to decedent) or to humanity as a whole (then: connectedness to living entities). | “On our last trip to India, suddenly there were all these many people. I was overwhelmed, or. And we all belong together”; “just my husband, that you can feel so connected to a human that you can have someone who can be so close to you and where you can go together like this” |

| to a greater whole | that the previously reported dimension is connected to a general greater whole/an all-embracing entity; is not coded, when universe, nature, or other humans are explicitly emphasized (then: connectedness to universe, nature, or other humans); is not coded when higher spiritual being is emphasized (then: connectedness to higher spiritual being/God) | “Simply connectedness with the greater whole of which we are part”; “Tears came to my eyes: For a brief moment, I realized that we are part of somehow a whole” |

| to all living entities (generic) | that the previously reported dimensions is connected to all living entities, such as humanity, fauna, flora, and/or the planet; is not coded when only the universe, the nature, other humans, or an unspecific greater whole is emphasized (then: connectedness to universe/nature/other humans/greater whole). | “It’s very important, for example, to realize that every dachshund on the street is just as happy as I am. And also has the right to be happy”; “Whether tree or horse, ultimately it is the life that is in all of us. It connects us and at the same time it demands a responsible and sustainable coexistence” |

| to decedents (generic) | that the previously reported dimension is connected to deceased fellow humans; is not coded when a connection to a saint is expressed (then: connectedness with immaterial sphere). | “I do not have to go to church. I possess what I have in my heart. I think about my father, my mother, almost every day”; “I’m quite honest now: when I’m alone, I often talk to my deceased parents” |

| Depth dimension of connectedness | ||

| to self | that the previously reported dimension is connected to the own self/soul/inner entity and/or expresses self-actualization or self-transcendence. Is not coded when a bodily connectedness is emphasized (then: connectedness to body). | “I believe that every person has […] something divine inside [...] And I want that for me, that I can find a way, that I can be like that, that I am at one with myself”; “For me, [Buddhism] is […] centered on one’s own person, when it comes to personal enlightenment. So, on the one hand, it is the responsibility of the individual to work on oneself and find one’s own way” |

| to body | that the previously reported dimension is connected to the own body; is not coded when a more non-physical connection to the own self is emphasized (then: connectedness to self). | “I feel what I have to eat, my body tells me, I’m in an exchange with my body”; “Then hiking, fasting, taking nature in […] I could feel my heart. I felt a warmth in my body. [Spirituality] takes place very much between my spirit [..] and my organs” |

Note. * All definitions follow Huber and Huber (2012). ** Definitions follow Bucher (2014), except of generic codes, which were induced from the empirical data.

References

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altmeyer, Stefan, Constantin Klein, Barbara Keller, Christopher F. Silver, Ralph W. Hood, and Heinz Streib. 2015. Subjective definitions of spirituality and religion: an exploratory study in Germany and the US. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 20: 526–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Edward. 2001. Implicit Religion in Contemporary Society. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, Allen H., and Paul F. Lazarsfeld. 1979. Einige Funktionen von qualitativer Analyse in der Sozialforschung [Some funtions of qualitative analysis in social research]. In Qualitative Sozialforschung. Edited by Christel Hopf and Elmar Weingarten. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, pp. 41–89. [Google Scholar]

- Berghuijs, Joantine, Jos Pieper, and Cok Bakker. 2013. Conceptions of spirituality among the Dutch population. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 35: 369–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, Anton A. 2014. Psychologie der Spiritualität, 2nd ed. The Psychology of Spirituality. Beltz: Weinheim. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt. 2017. Measures of Spirituality/Religiosity: Description of concepts and validation of instruments. Religions 8: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, Jeremiah. 2018. Spiritual, but not religious? On the nature of spirituality and its relation to religion. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 83: 261–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, Siobhan. 2008. The social ethic of religiously unaffiliated spirituality. Religion Compass 2: 240–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte-Sponville, André. 2009. The Book of Atheist Spirituality: An Elegant Argument for Spirituality without God. London: Transworld. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, Clemens, Constantin Klein, Anne Swhajor-Biesemann, Uwe Drexelius, Barbara Keller, and Heinz Streib. 2016. Dimensions of "spirituality": The semantics of subjective definitions. In Semantics and Psychology of Spirituality. Edited by Heinz Streib and Ralph W. Hood. Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 125–51. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, Robert A. 1999. The Psychology of Ultimate Concerns: Motivation and Spirituality in Personality. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the study of religious commitment. Religious Education 57: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grom, Bernhard. 2009. Religionspsychologie. The Psychology of Religion. München: Kösel. [Google Scholar]

- Hackbarth-Johnson, Christian, and Martin Rötting. 2019. Einleitung [Introduction]. In Zukunft der Spiritualität. Edited by Martin Rötting and Christian Hackbarth-Johnson. Sankt Ottilien: EOS, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Peter C., and Ralph W. Hood, eds. 1999. Measures of Religiosity. Birmingham: Religious Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Peter C., Kenneth I. Pargament, Ralph W. Hood, Michael E. McCullough Jr., James P. Swyers, David. B. Larson, and Brian J. Zinnbauer. 2000. Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Ralph W. 2003. The relationship between religion and spirituality. In Defining Religion. Investigating the Boundaries between the Sacred and Secular. Edited by Arthur L. Greil and David G. Bromley. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 241–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Ralph W., Peter C. Hill, and Bernard Spilka. 2009. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach, 4th ed. Guilford Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Houtman, Dick, and Stef Aupers. 2007. The spiritual turn and the decline of tradition: The spread of post-Christian spirituality in 14 Western countries, 1981–2000. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan. 2003. Zentralität und Inhalt: Ein neues multidimensionales Messmodell der Religiosität. Centrality and Content: A new multidimensional measurement model of religiosity. Opladen: Leske + Budrich. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2009. Religion Monitor 2008: Structuring Principles, Operational Constructs, Interpretive Strategies. In What the World Believes: Analysis and Commentary on the Religion Monitor 2008. Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, William. 1902. The Varieties of Religious Experience. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, Brick, Guy McCormack, Dong Pil Yoon, and Marian L. Smith. 2012. Convergent/divergent validity of the brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality: Empirical support for emotional connectedness as a “spiritual” construct. Journal of Religion and Health 51: 529–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, Barbara, Constantin Klein, Anne Swhajor-Biesemann, Christopher F. Silver, Ralph Hood, and Heinz Streib. 2013. The semantics of ‘spirituality’ and related self-identifications: A comparative study in Germany and the USA. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 35: 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, David B., and Teresa L. DeCicco. 2009. A viable model and self-report measure of spiritual intelligence. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 28: 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold. G. 2008. Concerns about measuring “spirituality” in research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196: 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckmann, Thomas. 1967. The Invisible Religion: The Problem of Religion in Modern Society. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, Douglas A. 2000. Spirituality: Description, measurement, and relation to the five factor model of personality. Journal of Personality 68: 153–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, Joey, and Daniel V. A. Olson. 2018. Is ‘spiritual but not religious’ a replacement for religion or just one step on the path between religion and non-religion? Review of Religious Research 60: 503–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Miller, Andrea J., and Everett L. Worthington Jr. 2013. Connection between personality and religion and spirituality. In The Psychology of Religion and Spirituality for Clinicians. Edited by Jamie D. Aten, Kari A. O’Grady and Everett L. Worthington. New York: Routledge, pp. 115–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1999. The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and no. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickel, Gert. 2013. Religionsmonitor-Verstehen was Verbindet: Religiosität im Internationalen Vergleich [Religionsmonitor–to Understand What Connects: Religiosity in International Comparison]. Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/GP_Religionsmonitor_verstehen_was_verbindet_Religioesitaet_im_internationalen_Vergleich.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 1999. Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? Spiritual transcendence and the five-factor model. Journal of Personality 67: 985–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 2004. Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments. Baltimore: Technical Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, Detlef, and Gert Pickel. 2007. Religious individualization or secularization? Testing hypotheses of religious change–the case of Eastern and Western Germany. The British Journal of Sociology 58: 603–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, Detlef, and Gergely Rosta. 2017. Religion and Modernity: An International Comparison. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2009. Implizite Religiosität: Zur Psychologie des Lebenssinns. Implicit Religiosity: Psychology of the Meaning of Life. Lengerich: Pabst. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypińska, Katarzyna. 2014. The threefold nature of spirituality (TNS) in a psychological cognitive framework. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 36: 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and Charles Y. Glock. 1968. American Piety: The Nature of Religious Commitment. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stausberg, Michael. 2015. The psychology of religion/spirituality and the study of religion. Religion Brain & Behavior 5: 147–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensland, Brian, Xiaoyun Wang, and Lauren Chism Schmidt. 2018. Spirituality: What Does it Mean and to Whom? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57: 450–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stifoss-Hansen, Hans. 1999. Religion and spirituality: What a European ear hears. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 9: 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streib, Heinz, and Ralph W. Hood. 2011. “Spirituality” as privatized experience-oriented religion: Empirical and conceptual perspectives. Implicit Religion 14: 433–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streib, Heinz, and Ralph W. Hood. 2016. Understanding “Spirituality”: Conceptual considerations. In Semantics and Psychology of Spirituality. Edited by Heinz Streib and Ralph W. Hood. Berlin: Springer, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tillich, Paul. 1957. Dynamics of Faith. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Yunping, and Fenggang Yang. 2018. Internal diversity among “spiritual but not religious” adolescents in the United States: A person-centered examination using Latent Class Analysis. Review of Religious Research 60: 435–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincett, Giselle, and Linda Woodhead. 2016. Spirituality. In Religions in the Modern World. Edited by Linda Woodhead. London: Routledge, pp. 323–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wulff, David M. 1997. The Psychology of Religion, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, David. 1998. Spirituality. In Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Edited by William H. Swatos. Walnut Creek: AltaMira, p. 492. [Google Scholar]

- Yinger, J. Milton. 1970. The Scientific Study of Religion. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2005. Religiousness and spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian. J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Brenda Cole, Mark S. Rye, and Eric M. Butfer. 1997. Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 36: 549–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, Christian, and Constantin Klein. 2012. Deutschsprachige Fragebögen zur Messung von Religiosität/Spiritualität: Stellenwert, Klassifikation und Auswahlkriterien [Measuring Religiosity/Spirituality: Theoretical Differentiations and Categorization of Instruments]. Spiritual Care 3: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | see http://p3.snf.ch/Project-156241 [26/08/2019]. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).