Structures of Organisation and Loci of Authority in a Glocal Islamic Movement: The Tablighi Jama’at in Britain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. A Quiet Revolution: The Spiritual Soft Power of a Global Islamic Movement

1.2. A Historical Précis of TJ in Britain

1.3. A Methodological Excursus

2. Dewsbury as A Central Hub

- -

- “To make provisions for the religious education of Muslim adults and children;

- -

- To arrange and hold religious gatherings;

- -

- To establish mosque and religious education schools;

- -

- To attempt to create understanding of the Muslim religious issues amongst government institutions6;

- -

- To make arrangements for groups of persons to visit mosques in the United Kingdom and overseas for the purpose of religious learning and spiritual self-rectification.”

“So what happened was, Hafiz sahib, initially … he worked for a few weeks in Preston … Because the work was in Preston, a factory called Courtaulds … So Hafiz sahib and Ishaq Patel8—two of the … founders of Tabligh in this country, they got a job in Courtaulds … then because of the incident in Courtaulds [they were refused time off to offer their Friday prayers] they left and went to Nuneaton. There was no markaz established in Dewsbury at that time, and even though there was a community of Muslims there, Gujarati Muslims, they didn’t have an alim (religious scholar), they didn’t have a hafiz (somebody who has memorised the Qur’an). But they’d heard about Hafiz Patel, so they said this person in Nuneaton, why don’t we bring him over? So they actually sort of head-hunted him to come to Dewsbury, and that’s how it all [began] … He was the imam there and then established the markaz there, so that’s how Dewsbury became a foundation … Allah’s will that it happened in Dewsbury.”9

3. TJ and the Local Mosques

3.1. Accessing Mosques of Different Denominational Affiliations

3.2. TJ Maraakiz and the Authority of the Sunna

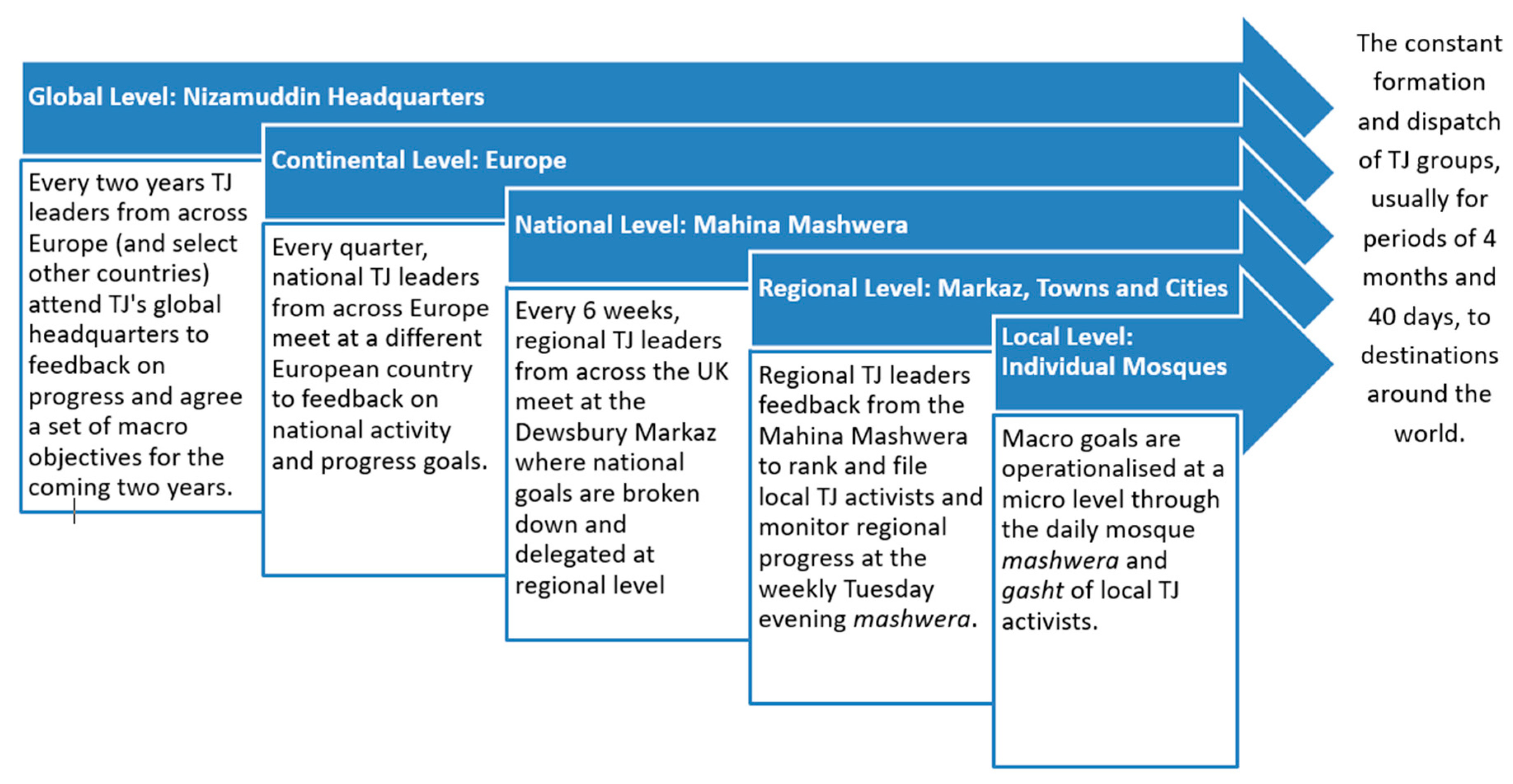

4. Ministering the Nation: Regional and Local Divisions of TJ

5. The Functioning of a Regional Markaz

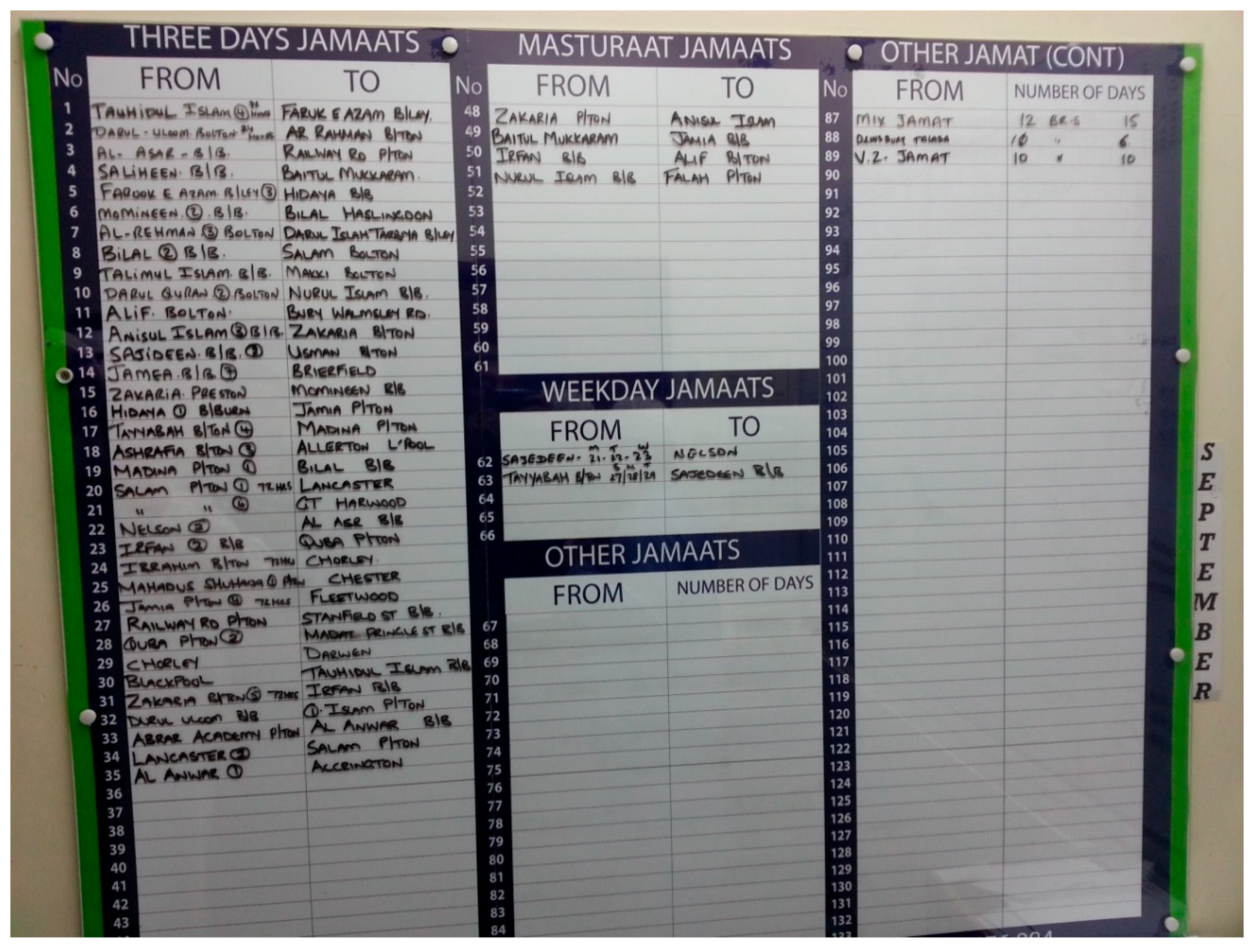

- There are 35 men’s jama’ats (usually between 8–15 members each) expected that weekend and four ladies’ groups (usually comprising 4–6 husband-wife couples each);19

- Of the men’s jama’ats, five are ready for the full 72 hours (Thursday to Sunday evening), while the majority are for the weekend only (Friday to Sunday evening), and one is only for 24 hours;

- Two weekday jama’ats are also expected (usually consisting of taxi drivers and restaurant workers who find it difficult to join the normal groups due to their occupational commitments over the weekend);

- All the above refer to the weekly 2–3-day TJ outings to be formed, organised and dispatched within the halqa. Additionally, three groups (under the heading ‘Other Jamaats’) are visiting mosques in Lancashire from outside the halqa. These comprise the following:

- A “mixed group” (i.e., the individual members hail from different parts of the UK) of 12 people that is probably out for 40 days in total and is spending 15 days in this halqa;

- A 10-strong group of ‘Dewsbury talaba’ (i.e., students of the Dewsbury Dar al-Ulum) that is visiting the halqa for 6 days;

- ‘V.Z. Jamat’—i.e., a foreign TJ group from Venezuela visiting the halqa (via Dewsbury, of course) for 10 days and probably in the UK for 40 days in total.

6. On the Interface of the Local and Global: TJ’s “Glocal” Activism

“It was really the next level and masha’Allah, you know, I met so many people from around the world and I did meet committed people so it was a real kind of, the performance bar was increased, you know, you saw people who were giving so many hours a day and they were very devoted to the teachings of Islam and yeah, it was a really good environment to be in … it felt like a genuine, I mean basically the layout was almost like a business plan which is: this is what we want to achieve, these are the outcomes that we want to achieve, these are the kind of performance indicators, you know, it was like a very clear business plan. How people can benefit from the religion of Islam and how the Muslims can be a source of benefit for mankind and serve mankind and be a source of good for mankind. And again, that resonated with me, and it seemed like a very clear game plan which I’ve heard lots of other groups of people but I never saw a very practical, clear plan as this.”

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, Mumtaz. 1991. Islamic Fundamentalism in South Asia: The Jama’at-Islami and the Tablighi Jama’at of South Asia. In Fundamentalisms Observed. Edited by Martin E. Marty and Scott R. Appleby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Abdul-Azim. 2019. Conceptualising Mosque Diversity. Journal of Muslims in Europe 8: 138–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Jan Ashik. 2012. Islamic Revivalism Encounters the Modern World: A Study of the Tablighi Jama’at. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Amrullah, Eva F. 2011. Seeking sanctuary in ‘the age of disorder’: Women in contemporary Tablighi Jamā’at. Contemporary Islam 5: 135–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balci, Bayram. 2015. The rise of the Jama’at al Tabligh in Kyrgyzstan: The revival of Islamic ties between the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia? Central Asian Survey 31: 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, Jonathan, and Sophie Gilliat-Ray. 2010. A mosque too far? Islam and the limits of British multiculturalism. In Mosques in Europe: Why A Solution Has Become A Problem. Edited by Allievi Stefano. London: Alliance Publishing Trust—Network of European Foundations. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, Jonathan, and Philip Lewis. 2012. The Pattern of Islamic Reform in Britain: The Deobandis Between Intra-Muslim Sectarianism and Engagement with Wider Society. In Producing Islamic Knowledge: Transmission and Dissemination in Western Europe. Edited by van Bruinessen and Stefano Martin. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, Innes. 2014. Medina in Birmingham, Najaf in Brent: Inside British Islam. London: C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, Amanda. 1999. The Ethnographic Self: Fieldwork and the Representation of Identity. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- DeHanas, D. N., and Z. P. Pieri. 2011. Olympic Proportions: The Expanding Scalar Politics of the London ‘Olympics Mega-Mosque’ Controversy. Sociology 45: 798–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhorat, Muhammad Saleem. 2018. Hafiz Muhammad Patel Sahib. Riyadul Jannah 27. [Google Scholar]

- Geaves, Ron. 1996. Sectarian Influences Within Islam in Britain with Reference to the Concepts of ‘ummah’ and ‘community’. Edited by Kim Knott. Leeds: University of Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, Abdus Sattar. 2018. Global leadership split in Tablighi Jamaat echoes in San Francisco Bay Area. Available online: https://countercurrents.org/2018/10/global-leadership-split-in-tablighi-jamaat-echoes-in-san-francisco-bay-area (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Gilliat-Ray, Sophie. 2006. Educating the Ulama: Centres of Islamic religious training in Britain. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 17: 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, Katja M. 2009. The politics of names: Rethinking the methodological and ethical significance of naming people, organizations, and places. Qualitative Research 9: 411–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Sadek. 2011. British Muslim Young People: Facts, Features and Religious Trends. Religion, State and Society 39: 247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Sadek. 2015. Sufis, Salafis and Islamists: The Contested Ground of British Islamic Activism. London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, Martyn, and Paul Atkinson. 2007. Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 3rd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Sajid. 2018. A House Divided. Dawn. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1391624 (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Janson, Marloes. 2014. Islam, Youth and Modernity in the Gambia: The Tablighi Jama’at, The International African Library. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Arsalan. 2016. Islam and Pious Sociality: The Ethics of Hierarchy in the Tablighi Jamaat in Pakistan. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Anthropology 60: 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, John. 2002. Tablighi Jamaat and the Deobandi mosques in Britain. In Global Religious Movements in Regional Context. Edited by John Wolffe. Bath: Ashgate Publishing Ltd in Association with The Open University. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnvall, Catarina, and Ted Svensson. 2017. Ontological security and the limits to a common world: Subaltern pasts and the inner-worldliness of the Tablighi Jama’at. Postcolonial Studies 20: 333–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Philip. 1994. Islamic Britain: Religion, Politics and Identity among British Muslims. London: I.B.Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, Danny. 2012. The Islamic Republic of Dewsbury. Batley: The Press News Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Luck, Taylor. 2015. The Mysterious Islamic Movement Quietly Sweeping the Middle East. Available online: http://www.csmonitor.com/World/2015/1206/The-mysterious-Islamic-movement-quietly-sweeping-the-Middle-East (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Madden, Raymond. 2010. Being Ethnographic. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Mandaville, Peter. 2001. Transnational Muslim Politics: Reimagining the Umma. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mandaville, Peter. 2010. Muslim Networks and Movements in Western Europe. Washington, DC: The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. [Google Scholar]

- Masud, Muhammad Khalid, ed. 2000. Travellers In Faith: Studies of the Tablighi Jama’at as a Transnational Islamic Movement for Faith Renewal. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, Barbara. 1994. Remaking Ourselves: Islamic Self-Fashioning in a Global Movement of Spiritual Renewal. In Accounting for Fundamentalisms: The Dynamic Character of Movements. Edited by Martin E. Marty and Scott R. Appleby. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mogra, Imran. 2014. The Tablighi Jama’at in the UK. In Islamic Movements of Europe: Public Religion and Islamophobia in the Modern World. Edited by Frank Peter and Rafael Ortega. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, Farish. A. 2012. Islam on the Move: The Tablighi Jama’at in Southeast Asia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, Zacharias. 2012a. The Contentious Politics of Socio-Political Engagement: The Transformation of the Tablighi Jamaat in London. Ph.D. thesis, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, Zacharias. 2012b. Tablighi Jamaat—Handy Books on Religion in World Affairs. London: Lapido Media. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, Zacharias. 2015. Tablighi Jamaat and the Quest for the London Mega Mosque: Continuity and Change. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Reetz, Dietrich. 2003. Keeping Busy on the Path of Allah: The Self-Organisation (Intizam) of the Tablighi Jama’at. In Islam in Contemporary South Asia. Edited by D. Bredi. Rome: Oriente Moderno. [Google Scholar]

- Reetz, Dietrich. 2008. The Faith Bureacracy of the Tablighi Jama’at: An Insight into their System of Self-organization. In Colonialism, Modernity, and Religious Identities: Religious Reform Movements in South Asia. Edited by Gwilym Beckerlegge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reetz, Dietrich. 2009. Tablighi Jama’at. In The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Islamic World. Edited by John Esposito. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sardar, Ziauddin. 2004. Desperately Seeking Paradise: Journeys of a Sceptical Muslim. London: Granta Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer, Abdallah, ed. 2018. The 10th Anniversary Edition, The World’s 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2019. Amman: The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Martin. 2016. ‘At least 5000’ mourners turn up to funeral of respected Muslim leader in Yorkshire town. The Mirror. Available online: http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/at-least-5000-mourners-turn-7404184 (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Siddiqi, Bulbul. 2018. Becoming ‘Good Muslim’: the Tablighi Jamaat in the UK and Bangladesh. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sikand, Yoginder S. 1998a. The origins and Development of Tablighi-Jama’at (1920–2000): A Cross-Country Comparative Study. Ph.D. thesis, University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Sikand, Yoginder S. 1998b. The origins and growth of the Tablighi Jamaat in Britain. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 9: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikand, Yoginder S. 2002. The Origins and Development of Tablighi-Jama’at (1920–2000): A Cross-Country Comparative Study. Hyderabad: Orient Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Jenny. 2015. Understanding and Engaging with the Tablighi Jamaat. Lausanne Global Analysis 4. Available online: https://www.lausanne.org/content/lga/2015-11/understanding-and-engaging-with-the-tablighi-jamaat (accessed on 21 June 2019).

- Timol, Riyaz. 2015. Religious Travel and the Tablighī Jamā‘at: Modalities of Expansion in Britain and Beyond. In Muslims in the UK and Europe I. Edited by Yasir Suleiman. Cambridge: Centre of Islamic Studies, University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Timol, Riyaz. 2016. Obituary: Hafiz Patel (1926–2016)—‘A Spiritual Giant in an Age of Dwarfs’. Available online: http://www.onreligion.co.uk/blogs/obituary-hafiz-patel-a-spiritual-giant-in-an-age-of-dwarfs/ (accessed on 28 February 2016).

- Timol, Riyaz. 2017. Spiritual Wayfarers in a Secular Age: The Tablighi Jama’at in Modern Britain. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Janson’s (2014) analysis of TJ’s support base in The Gambia similarly identifies a core constituency of English-speaking, secular-educated youth. This challenges Sikand’s dated assumption, based largely on the impassioned invectives of Gloucester-based pamphleteer Ebrahim Rangooni and the opinions of Hizb ut-Tahrir spokesperson Farid Kassim, that “The Tablighi Jama’at has very little presence among Muslim students in British schools and colleges” (Sikand 1998b, pp. 185–86). |

| 2 | Hamid’s important book Sufis, Salafis and Islamists does not mention TJ once, while his paper British Muslim Young People: Facts, Features and Religious Trends erroneously states that “The seminary in Bury in North-West England is…the international headquarters of the international Tablighi Jamaat missionary movement” (Hamid 2011, p. 256). |

| 3 | See, for instance, https://www.okhlatimes.com/tablighi-jamaat-members-clash-markaz/ (accessed 21 June 2019). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Reproduced from the Annual Report filed with the Charity Commission for the year ending 31 December, 2014: http://apps.charitycommission.gov.uk/Showcharity/RegisterOfCharities/CharityWithPartB.aspx?RegisteredCharityNumber=505732&SubsidiaryNumber=0 (accessed 21 June 2019). |

| 6 | Although a stated aim, in practice it appears that the British branch of the Tablighi Jama’at has preferred to eschew all but necessary contact with government throughout its history. This becomes all the more apparent when their approach is contrasted with other organisations such as the Muslim Council of Britain for example. |

| 7 | For more on Hafiz Patel, see the series of articles penned by the respected Leicester-based Deobandi scholar Maulana Muhammad Saleem Dhorat (2018). Although the Sufi roots of the Tablighi Jama’at are undeniable, the extent to which it can be considered a Sufi movement today is contested in the academic literature, and the movement has generally preferred to downplay public expressions of Sufism throughout its history. |

| 8 | This seems to be the same Ishaq Patel reluctantly interviewed by Ron Geaves (1996, pp. 171–77) during his visit to Dewsbury Markaz in 1993. |

| 9 | Sikand (1998b, p. 180) has essentially the same account, although he makes no mention of the stint in Preston and has Hafiz Patel moving to Dewsbury from Coventry rather than Nuneaton. All respondents I interviewed have been anonymised to protect their identity. |

| 10 | See www.MuslimsInBritain.org (accessed 21 June 2019). The statistics are derived from a downloadable PDF report compiled on 16 September 2017: http://www.muslimsinbritain.org/resources/masjid_report.pdf. |

| 11 | Although TJ is officially banned in the Kingdom, I was informed by the group it has a discreet yet robust presence—as is the case in several Middle Eastern countries (see the fascinating article published by the Christian Science Monitor: The mysterious Islamic movement quietly sweeping the Middle East (Luck 2015)). |

| 12 | However, according to Ahmed (2019, p. 150): “The members of the mosque leadership are equally from Pakistani and Middle-Eastern backgrounds, though its congregation is more diverse...” Having personally visited the mosque on several occasions, I think a more accurate descriptor would simply be “cosmopolitan”—which brings into sharp relief the problems inherent in ascribing labels to people, mosques or organisations that inevitably evolve over time, and the “dynamics of power inherent in the act of naming” (Guenther 2009, p. 412). |

| 13 | Such an arrangement does not exist in the “congregational polity” of many post-Reformation denominations. |

| 14 | With the Diocese in Europe, the total is 42; see https://www.churchofengland.org/about-us/dioceses.aspx (accessed 21 June 2019). |

| 15 | See http://catholicfaith.org.uk/Home/Ask-Find/Find-a-church (accessed 21 June 2019). |

| 16 | The reference is to Maulana Muhammad Sa’ad Kandhalwi, great-grandson of TJ’s founder, although of course this all refers to the situation before the schism outlined in Section 1.2. In recent years, Maulana Sa’ad’s authority has been increasingly contested, and rejected outright by some, in TJ circles, leading to the undermining of the authority of both the Dewsbury and Nizamuddin headquarters for many British Tablighis. However, as stated in Section 1.2, the content of this paper reflects the situation as it was during the period of my fieldwork over 2013–2015, and fresh fieldwork would be required to accurately map subsequent developments. |

| 17 | See: http://daruliftaa.com/blessed-effort-of-jamaah-al-tabligh (accessed 21 June 2019). |

| 18 | The bulk of Pieri’s (2012a, p. 39) participant observation consisted of attending the weekly Thursday night gatherings at London Markaz—“150 hours (roughly 55 separate sessions) over a period of 18 months were spent attending these talks, followed by further time socialising over a meal in the mosque afterwards”—where he observed that a more ethnically diverse crowd of up to 3000 would gather each week. |

| 19 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Timol, R. Structures of Organisation and Loci of Authority in a Glocal Islamic Movement: The Tablighi Jama’at in Britain. Religions 2019, 10, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100573

Timol R. Structures of Organisation and Loci of Authority in a Glocal Islamic Movement: The Tablighi Jama’at in Britain. Religions. 2019; 10(10):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100573

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimol, Riyaz. 2019. "Structures of Organisation and Loci of Authority in a Glocal Islamic Movement: The Tablighi Jama’at in Britain" Religions 10, no. 10: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100573

APA StyleTimol, R. (2019). Structures of Organisation and Loci of Authority in a Glocal Islamic Movement: The Tablighi Jama’at in Britain. Religions, 10(10), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100573