1. Introduction

Indonesia is the country with the largest Muslim majority population in the world. At the end of 2017, a population census noted that the country had 265 million inhabitants, with 87.2 percent being Muslim. The country became independent from Dutch Colonial rule in 1945. Indonesia became one of the nations that have grown steadily over the last several decades, despite experiencing revolution and conflict at the beginning of its independence. As a developing country, Indonesia seeks to develop the prosperity of its population, open up various industrial sectors, trade, and advanced agriculture for food security.

Besides having a wealth of biodiversity and being included in the State of Megadiversity (

Mittermeier and Mittermeier 1997), the country also has abundant mineral wealth, such as nickel, copper, and bauxite. This wealth is one of the cornerstones of exploitation and foreign and domestic investment. Indonesia is also rich in agriculture and plantations. The country is very dependent on natural products including natural forests and all forest resources that come from them and can become commodities. But biogeographic areas in this country such as Sundaland (Sumatra, Kalimantan and Java) and Wallacea (Sulawesi, Maluku and Nusa Tenggara) are categorized as hotspot areas, that is, areas that have high biodiversity and endemicity, but are threatened by excessive exploitation (

Mittermeier et al. 1999;

Myers et al. 2000).

The religion of Islam entered Indonesia and developed between the 7th and 13th centuries CE, which was proven by the existence of kings from the Indonesian kingdom who wrote and asked for instructions on the teachings of Islam and then embraced it.

1 After that, Islam developed in the archipelago and experienced a period of glory with sultans and small kingdoms oriented to the caliphate that developed, especially in the Ottoman Age.

Islamic rule developed in the 13th century and experienced a peak of the 15th century until the 18th century, when the period of European colonialization went on in several islands and controlled several kingdoms in the archipelago. After the era of independence, Indonesia declared itself as a nation state. The kingdoms in the archipelago joined together to become a unitary state: the Republic of Indonesia, which later became sovereign and independent in 1945.

The roots of Islam as a religion has been inherited for a very long time. Many classical texts on Islamic teachings, including fiqh books, were written in Arabic script but in the Malay language. The governmental system is including the prevailing government system was the kingdom or empire of Islam, where Islamic law was adopted as the law of the State and the king was always accompanied by the ulema, such as the Mufti. The Islamic Sultanate (Mamluk) in the Archipelago applied Islamic law, but this law was later replaced by Dutch colonial law. Religious teachings like those of

muamalah and worship, have long been guided by what is taught by scholars who have studied in the Middle East. In addition, in the 17–18th century, the development of Islam was supported by a network of Indonesian scholars, especially those from Southeast Asia, networking with teachers and colleagues in the Middle East (

Azra 1998), therefore, as a country growing in a culture with a Muslim majority population, Muslims in Indonesia really appreciate their scholars. Some religious organizations with very large followings, such as Muhammadiya, founded in 1912, and the Nahdatul Ulama (established in 1926), were founded by ulama as leaders. The advice of scholars, for Muslims in the archipelago, is a guideline that can direct them in their religious life, because the cleric is the authority in providing answers and guidance in practical matters of religion. A narration of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), said:

“Indeed, the ulama ‘are the heirs to the prophets. Indeed the prophets did not inherit the dinar or dirham. But they inherit knowledge. Whoever seizes it has taken a bountiful share indeed.”

Some of these scholars, then, not only became leaders in the community, but their advice and commands also became guidelines, especially in carrying out daily religious life. However, after experiencing independence from the Dutch colonial invaders, the State of Indonesia became a republic with all its dynamics wanting to achieve economic prosperity and social justice. The Indonesian government adheres to a secular modern democratic system, but on the other hand, this country has a State guideline called Pancasila which requires all its citizens to believe in God Almighty.

The Republic of Indonesia was formed as a nation-state that respected and gave a place to various religions and ethnic groups. Since its establishment in 1945, the founders of this country have agreed on this policy, making Indonesia a nation-state by adopting five principles (Pancasila) as a view of statehood. Therefore, in principle, following the rules handed down by God is an accepted practice in national life.

2. The Role of Majlis Ulama Indonesia

The development of a massive environmental movement throughout the world has brought to Indonesia a regular and active movement of efforts to manage its environment. In recent decades, the role of religion in environmental action activities has been seen to be important, even recommended (

Bhaghwat et al. 2011). Several studies have been carried out even in early 2000, with the publication of the Harvard

Religion and Ecology series, including the Islam and Ecology (

Foltz et al. 2003).

Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), is an assembly that provides a place for Indonesian ulama leaders and Muslim scholars. MUI has an important role to fill and provides answers that are motivational about the practicalities of Muslims in carrying out the teachings of the Islamic religion. Equally important, in each discovery, the MUI provides clues to their interpretation of the teachings of Islam. MUI is a non-governmental organization that was established to respond to the needs of Muslims in providing certainty of religious teachings and their implementation within the framework of a plural country like Indonesia.

Since the establishment of the MUI in 1975, it has been noted that the MUI, according to the intentions of its birth, was a forum for connecting the Islamic scholars, leaders and intellectuals from various groups among Muslims. One important role of the MUI is in providing fatwas for Muslims. Even though a fatwa in Indonesia is not a positive law and is not legally binding, a fatwa is believed to be very influential in its implementation in the community. Muslims still want to base their lives on religious beliefs, because, if someone follows the law that is based on God’s precepts in the World, then there will also be the demands of God in the hereafter. MUI fatwas become an important reference guide for the religious life of Muslims, especially in Indonesia. And the fatwa continues to be an important reference in religious life, including in matters of al mu’amalah (conducting buying and selling transactions and social activities), as well as being a moral foundation in social life.

Also, as a developing country, the fatwas sometimes form the basis for laws which are then determined by the State and can become a positive law adopted by the state. Besides, the MUI fatwa can be adopted as a source of inspirational law for the state, an expert to Indonesia national law, Indrayana says:

“… The MUI fatwa is only an aspirational law that can be transformed into a positive law if it is enacted in a statutory regulation or decided in a judicial ruling with permanent legal force, and eventually becomes jurisprudence.”

3

As a multicultural nation-state, Islamic law in Indonesia is not positive law, but a moral law that can inspire the best choices in carrying out daily activities, especially among Muslims. In short, the MUI fatwa can be classified as a source of material law and a non-binding source of law (

Suhartono 2018).

In its historical record, MUI was formed as an independent institution. In its independence, this institution established cooperation on a basis of with mutual respect and did not deviate from this vision, mission and function. It remains as originally intended, a forum for the scholarly network and leadership from various groups among Muslims.

It is said in its history

4 that the establishment of the MUI was also related to the awareness of the diversity of the Indonesian nation, is a unique feature that must be maintained, therefore it is also necessary to live side by side and work together among other national components for good and progress. In the end, MUI wants their role to be one of contributing and endeavouring to realize Islam as grace to all the universe.

MUI was founded to provide religious instructions and answers to the questions of Muslims. Although the fatwa is seen as a non-binding regulation for anyone who wants to obey it, as a doctrine derived from Islamic teachings, a fatwa is a guide for Muslims in seeking answers and certainty—especially about religious law—for their religious practice. The search for forms of implementation of sharia law has experienced different developments in various places, including good developments in Aceh (

Yasa 2015).

After more than 44 years, MUI’s very prominent role is in giving fatwas to Muslims.

La Jamaa (

2018), examining all fatwas issued by MUI from 1975 to 2011 produced 137 fatwas, and 50 decisions in total, aimed both at Muslims and the Indonesian government. The fatwa for the last 26 years has contributed positively to the transformation of contemporary Islamic law in Indonesia.

The confidence in the MUI fatwas, which were then followed by the community, then promoted the dynamics of Islamic Sharia instructions based on the Koran, that were later adopted as binding laws promulgated publicly as part of civil law in a modern state. Some examples are Law No. 1 of 1974 concerning Marriage Law; No. 10 of 1998 concerning Banking; Law No. 17 of 1999 concerning the Implementation of Hajj; Law No. 38 of 1999 concerning Management of Zakah; Law Number 41 of 2004 concerning Waqf, and Law No. 21 of 2008 concerning Sharia Banking. Also there is Law No. 44 of 2008 concerning Pornography; Law No. 50 of 2009 concerning Religious Courts; Law No. 33 of 2014 concerning Guaranteed Halal Products, and Law No. 34 of 2014 concerning Hajj Financial Management.

3. Environmental Conservation Fatwas

The request for fatwa is a way to guide Muslims in Indonesia in their lives who want to base their lives on religious law, which began in the 1980s. Engagement activities with ulama have also been carried out during President Soeharto’s efforts to bring development efforts closer to the community including sanitation and water issues in collaboration with UNICEF. Besides, there was also a fatwa on limiting population growth through the Family Planning Program (KB) as a result of the MUI National Conference in the 1980s. The fatwa later became the driving force behind the success of the National Family Planning Movement that was enacted by the government in 1982. The limitation on the number of children in the family planning program was not easily accepted by the community, especially Muslims, because this involved their beliefs. The fatwa support the development program by stated among other:

“Islamic teachings approve family planning for the health of children, and children, education of children to be healthy, intelligent and pious.”

5

However, when religious leaders were involved, the effort was supported (

Warwick 1986). This program was so successful, that President Soeharto was asked to address the UN Session to explain about his experiences in 1992.

Hence, almost no more Fatwas related to the environment were issued by the MUI. It was only after 2009 that the MUI issued a fatwa again related to the environment. Therefore, some environmental conservation NGOs have become aware of the success of this approach and conducted some facilitation to work together with the religious leaders (

Mangunjaya 2011). Some fatwas issued by MUI related to the environment are as follows:

Fatwa 30 October 1983 Regarding Populations, Health & Development

6Fatwa 2/2010 Recycling Water for ablutions

Fatwa 22/2011 Environmentally Friendly Mining

Fatwa 4/2014 The Protection of Wildlife for The Balance of The Ecosystem

Fatwa 47/2014 The fatwa on Wastes Management

Fatwa No. 1/MUNAS-IX/MUI/2015 The Utilization of Zakat Infaq Shadaqah and Waqf (ZISWAF) for the Construction of Community Water & Sanitation

Fatwa 30/2016 The law of burning and land and forest

The edicts for the environment and biodiversity conservation constitute a response to Muslims wishing to know the Islamic perspectives regarding the preservation of wildlife and nature as well as the environment. As an institution that has religious authority to provide religious advice to the community, the MUI, as stated in its organizational regulations, says that the Indonesian Ulema Council has the authority to issue fatwas on shari’ah issues in general, both in the areas of faith, sharia, social relations, morals, culture, and the environment, by always upholding the principles of truth and the purity of religious practice by Muslims in Indonesia. The statement was made in the MUI Organizational Regulation.

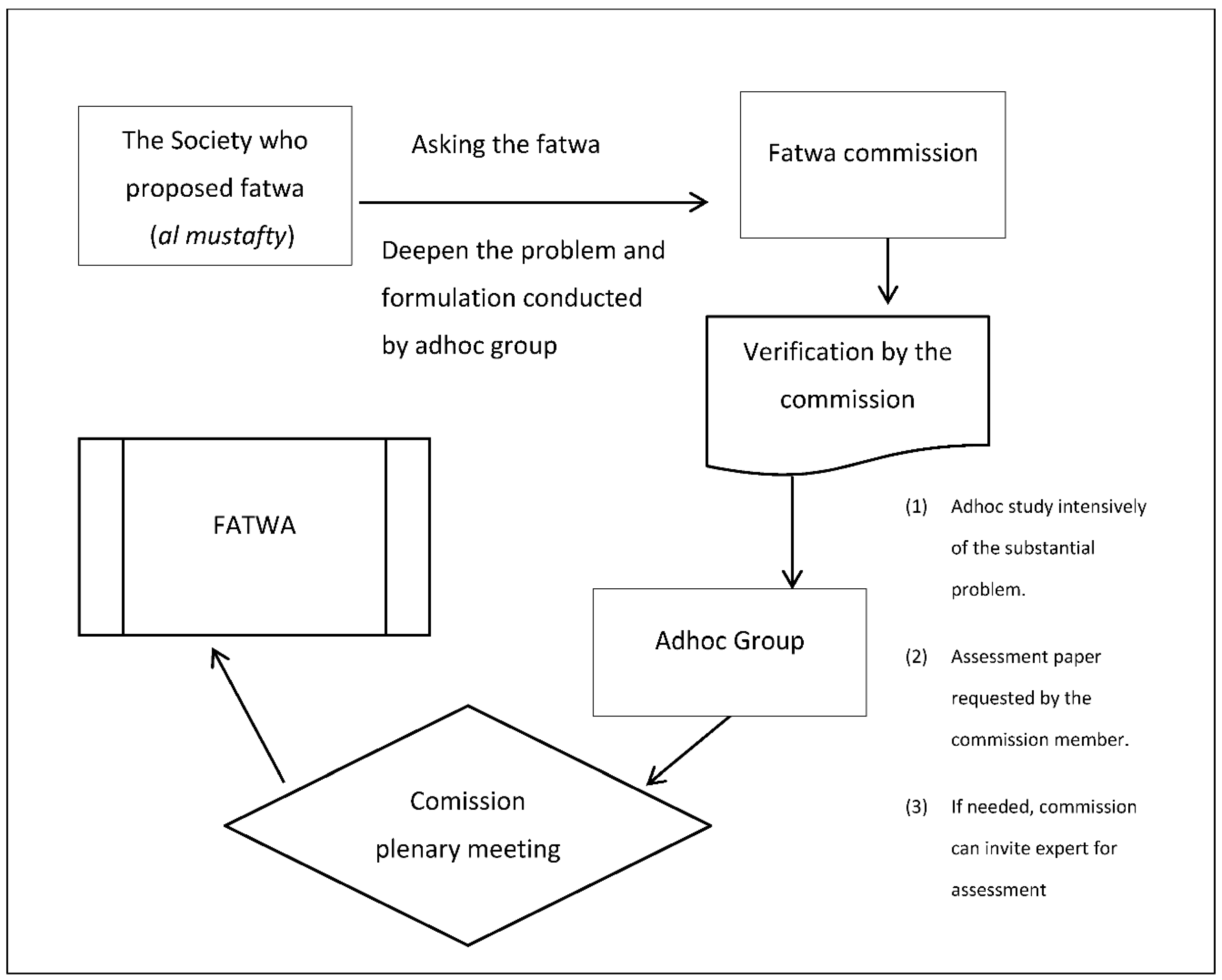

7The fatwa commission can carry out a process to determine the fatwa through several meetings and deliberations, because the fatwa is an answer

to requests or questions from the public;

to requests or questions from the government, institutions/organizations or MUI itself;

the development and findings related to religious problems that arise due to changes in society, advances in science and technology, culture and arts.

However the issuance of a fatwa is an attempt to get a view of how religion views an issue. Fatwas are discussed in Fatwa Commission hearings and issued with the signature of the fatwa commission and secretary of the fatwa commission (see

Figure 1).

The submission process in terms of fatwa submitted to MUI is shown in a recent official document published by PLHSDA-

Majelis Ulama Indonesia [MUI] (

2014) “Procedures for Determining and Applying Fatwas about the Environment and Management of Natural Resources.” It explains, by the way of introduction, that there are four kinds of “tasks and functions” involved in deriving a ruling (

Gade 2015):

the mustafti (the party seeking the fatwa);

the mufti (the author of the fatwa);

the issue to be determined; and,

the users of the fatwa or “related parties”.

The “framework” for developing and applying the fatwa includes a “workshop” to be attended by the mufti, the mustafti, as well as “experts in the area and personages from the society who will utilize the fatwa”. The goal at this stage of the process is to achieve a “comprehensive and holistic” formulation of the issue with an eye to an implementable solution, through “various sources of Islamic law” as well as “comparative study and/or field research.

In the process of releasing the fatwa, the stipulation of the fatwa, procedures, is stated in paragraphs 1 to 4 of Article 2. Paragraph 1 of the MUI Fatwa Guidelines stipulated in Decree of the MUI No. U-596/MUI/X/1997, such as the following: “Any fatwa must be based on Quran and the Prophet’s Sunnah, and

mu’tabarah8 guides, and must not be contrary to the common good. Paragraph 2 stipulates: in the event that those bases are not contained in the Quran and Sunnah as defined in paragraph 1 of Article 2, the fatwa decided should not conflict with

ijmā‘, mu‘tabar, qiyas (analogy), and other legal guides, such as

istiḥsān, Maslaḥah, Mursalah, and

Sadd al-Dhari’ah. Paragraph 3 states: before stipulating a fatwa, the opinions of the previous imams of the madhhab should be reviewed, both related to the legal guides and related to the guides used by those with dissenting opinions. Paragraph 4 states: the views of the relevant experts are to be considered when stipulating a fatwa.

4. Fatwa on the Conservation of Biodiversity

The Fatwa on endangered wildlife is an interesting example of a case involving religious teachings. Indonesia is known as a majority Muslim country which has a high wealth of flora and fauna. But more often these days, fears about the use of these resources such as the hunting and handling of wild animals have grown. Although Indonesia has more than 54 national parks, and various types of protected areas with various types of protected benefits, many protected animals are located outside conservation areas, for example 78% of the orangutan population are outside the area, and 60% protected species outside the area (

Wich et al. 2012). So, the existence of a conservation area does not guarantee the safety of certain species in their natural habitat because they are hunted or traded. Also, the conversion of natural habitats into plantations is also very extensive, such as land clearing for palm oil, cocoa, coffee and other commodities.

The emergence of Fatwa No. 4/2014, on the protection of endangered wildlife for the balance of the ecosystem is an attempt to find answers in overcoming the rampant illegal trade in protected animals and seeks to give empathy to every creature created by God, so that these creatures will not become extinct in nature and can carry out their function in protecting ecosystems for the benefit of humans.

This is an effort to actually find answers from the viewpoint of Islamic teachings, especially in responding to problems that may not have occurred in the centuries when Islamic Shari’a and Jurisprudence were applied. Islamic teachings provide a very important inheritance that has a positive impact on various types of endangered species that are protected, such as tigers, species of birds, reptiles, amphibians and primates, which are prohibited for consumption in Islamic teachings (

Al Banjari 1882). The ban has an impact on hunting because the community has no interest in eating these species (

Mangunjaya 2019). However, the complexity of the modern world, brings a new challenge, that the purpose of hunting now is not only for consumption, but the results can also be sold.

So the question arises: Is hunting animals that are forbidden as food also prohibited for sale? Because it is evident that many Muslims in the field hunt forbidden animals that are forbidden to eat, such as orangutans and tigers, but they sell them and get income from them. Requests have been submitted to the MUI, to consider the results of the MUI team’s activities in the field and several discussions and seminars to get clarity on the need for the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) Fatwa regarding: Protection and Preservation of tigers, rhinos, elephants, orangutans and other endangered species, especially in the effort to raise the awareness of Muslim communities where the pockets of habitat of endangered animals that have been damaged and threatened with extinction.

The crisis that threatens the existence of these species has become a concern of environmental experts, because in Indonesia, in particular, the exploitation of wild animals is increasing, due to the hobby (for example) by keeping birds in a cage, and many are also driven by economic needs. Hunting is also triggered by cultural factors in certain ethnic groups in Indonesia, due to the rampant trade in animals driven by economic activity (

Jepson and Ladle 2005). This crisis has caused scarcity in nature: certain species for example helmet hornbills, that had been ranked endangered, have now become critically endangered (

IUCN 2018).

In the country with the largest Muslim population in the world, then, the hope to provide awareness through Islamic teachings is an important effort. This was done considering the effectiveness of the movement that had been carried out by the previous government, in involving scholars through the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI):

Recognizing the importance of the role of ulama and its influence in guiding religious life that can be one of the keys to behavioral change in Indonesia, environmental activists made proposals to obtain a fatwa on the hunting and trading status of protected endangered species. This petition initiative was carried out by four institutions, namely: (1) Ministry of Environment and Forestry, (2) WWF Indonesia, (3) Fauna and Flora Internasional (FFI), (4) Forum Harimau Kita and (5) Center for Islamic Studies, Universitas Nasional (PPI-UNAS).

Starting with holding a dialogue and facilitation event organized by NGOs and PPI UNAS, in consultation with MUI PLH-SDA (

MUI 2016), the dialogue and meeting narrowed to the desire to obtain an MUI fatwa on animals—especially those that were protected and then traded. The letter was signed by the five institutions. In detail, the submission scheme can be seen in

Figure 1.

The Fatwa Commission then discusses and makes arguments based on the principles of fiqh and Islamic Sharia law on the subject in question. The Fatwa Commission in the MUI consists of 48 scholars who can gather to agree on the fatwa concept after going through debates and making important arguments and counter-arguments. In the process of making fatwas, especially in discussing contemporary issues, the MUI always consults with experts. They present experts to gain knowledge input in identifying problems. After there is identification and understanding of the problem, the muftis will look for the answers in the Qur’an. If there is an answer, it will be answered following what is in the verse in the Qur’an. If it is not in the Qur’an, it is sought in the Prophetic Sunnah (hadith), if it is not in the Sunnah, then the opinions of the ulama will be sought. Usually if it is included in the opinion of the ulema, then this is included in the area of conducting ijtihād (

Al Ayub 2019).

At a meeting to explore and identify the fatwa of protected endangered species. MUI presented several meetings with conservation experts, and dialogue was also held with the government and researchers. The MUI conducted field visits to ask the community about their conflict with wildlife, and what they really expect. The dialogue process for validating and deciding Fatwa No. 4/2014 took almost 10 months, was carried out from March 2013, and finalization and an official announcement were made in 2014.

The fatwa was written in a white paper with a supporting letter, totaling 15 pages, consisting of: remembering, weighing, paying attention and stipulating, containing a comprehensive discussion of Islamic principles towards all God’s creatures. The Fatwa for the Protection of Endangered Species for the Balance of Ecosystems No. 4/2014, provides important clauses:

Killing, harming, assaulting, hunting and/or engaging in other activities which threaten endangered species with extinction are forbidden, except for cases allowed under shariah, such as self-defense;

Illegal hunting and/or illegal trading of endangered species are haram (forbidden).

Besides, Fatwa No. 4. 2014 provides advice to other stakeholders to enforce this advice. The fatwa specifically mentions the importance of government involvement, parliament, businesses as well as religious and community leaders. For community leaders, for example, the fatwa message is to spread religious understanding on the need to maintain balanced ecosystems, especially by protecting endangered species; and to encourage creation of religious guidelines and the formation of “Environment Preachers” to establish public awareness on the need for environmental protection and conservation of endangered species.

According to the fatwa, every living organism has the right to sustain its life and may be used for human well-being. Hence, treating endangered species well by protecting and conserving them in order to ensure their well-being is mandatory.

The Islamic scholars emphasize that protecting and conserving endangered species shall occur by, among other things:

10Guaranteeing their primal needs, including food, shelter and the need to reproduce;

Not burdening them with loads (weight) beyond their capacities;

Not placing them in the vicinity of other animals which may harm them;

Conserving their habitats;

Preventing illegal hunting and the illegal wildlife trade;

Preventing human-wildlife conflict;

Maintaining animal welfare.

This fatwa was then disseminated in order to strengthen the activities of the protection of endangered species. Some conservation NGOs, in general, convey this fatwa to the Muslim communities on the sites where they work, both formally and informally. Eventually USAID documents related to the Biodiversity Handbook (

USAID 2015), appreciated MUI’s move to provide a fatwa on animal protection and said that the step represented the most advanced view in the Muslim world.

The issuance of this fatwa was enthusiastically welcomed by non-governmental organizations engaged in conservation. They also helped disseminate this fatwa, inviting imams and clerics to join together to campaign for the fatwa. The National University Center for Islamic Studies together with several NGOs and NGO partners implemented in the field, such as the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in Sumatra and Java, Fauna and Flora International (FFI) in Aceh, the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) in South Sumatra, International Animal Rescue Indonesia (IARI) in West Kalimantan etc.

The issuance of this fatwa later became a guideline for all scholars in the regions, especially those related to efforts to sensitize the public. With the existence of this fatwa, people increasingly now recognize that efforts to protect and preserve wildlife are part of Islamic teachings. Before that there was no straightforward explanation as to why animals were preserved, and why Muslims were encouraged to preserve them. “With this fatwa, our activities in the community in voicing about nature conservation including flora and fauna are getting louder. With our preachers, we implement the Islamic vision and mission for protection of the species, and community are aware to follow this”

11. Through the conservation preachers, we believe it will be easy to increase community understanding

12.

Fatwas are also expected to function as pre-emptive efforts in overcoming conflicts between animals and humans (

St. John et al. 2018). Non-governmental organizations and government activities are increasingly helped by the existence of this fatwa, especially in providing an understanding of the Islamic perspective on protected animals, also felt by Ujung Kulon National Park, which carries out activities by involving the preachers, by visiting village mosques especially during Ramadan. The national park staff conducted a get-together with the clerics conducting Ramadhan prayer (

tarawih) by traveling from mosque to mosque in the villages near Ujung Kulon National Park. By this means, hopefully the community surrounding the national park will be more aware of the importance of protecting its ecosystem.

Tjamin et al. (

2017) and

Mangunjaya et al. (

2018) observed there are increasing awareness among Muslims in Indonesia on their conservation intention for action after MUI released their edict. However, more effort should be conducted in the site particularly at the vicinity of conservation areas, particularly to involve their religious leaders.

5. The Fatwa on Burning Forest and Land

Forest fires are events that often occur in Indonesia. The cause of forest and land fires in Indonesia, was the work of several persons who were intentionally looking for profit. The biggest fire area in Sumatra is the Forest Production Area 51% and plantation 30%. So around 80% of the fires occur in the concession, and if this can be handled then the fire problem can be overcome.

In 2015, there were severe fires that hit Indonesia’s forests, especially on the islands of Kalimantan and Sumatra. The total area of forest and land fires reached 2.7 million ha with a total economic loss of 16.2 billion USD or 242 trillion rupiah. Losses incurred that can be assessed economically affected include flight activities, economic activities that were stopped due to fire and crop loss. On the other hand the number of victims of the Indonesian people who were exposed to smoke reached 40 million and 500 thousand developed acute respiratory infections (ISPA), which caused 19 deaths and more than 100,000 premature deaths (

The Guardian 2015). The impact of the haze also reached neighboring countries such as Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. Emergency status was declared by the government for six provinces, namely: Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, Central Kalimantan, West Kalimantan and South Kalimantan.

As a result of these fires, according to Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED) records, Indonesia’s CO

2 emissions increased to one billion tons, exceeding the annual emissions of Germany. During forest fires, Indonesia emits carbon emissions and pollutes the atmosphere with an average of 15–20 million tons of carbon per day, which exceeds 14 million tons of US daily emissions in support of factories and cars to run the economy (

Huijnen et al. 2016). The

World Bank (

2016), reported that Indonesia had an estimated loss of IDR 221 trillion, caused by the fire occurring from June to November that burned 2.6 million hectares of land and resulted in thick smoke and haze. These figures have not taken into account the losses in health and education. 37% of the 2.6 million hectares of land burned in 2015 was peatland. In fact, Peatland serves as a reservoir that can contain a huge amount of carbon.

The year 2015, indeed, was in the five-year cycle of El Niño, a regularly occurring weather anomaly, and because of complex series of climatic changes affecting the equatorial Pacific region including Indonesia, the El Niño in 2015, which according to experts was equal to the El Niño in 1998, it caused some months of drought, causing the forests in Kalimantan and Sumatra to be highly flammable. Fire could spread quickly and because there was also an interest in immediately clearing large tracts of plantations, by burning.

To tackle the disaster at the beginning of the fire of 2015, which was seen to be very severe, MUI issued

Tadzkirah or religious memorandum. This memorandum is a short letter, a circular disseminated to the public and says among other things:

First, the MUI called on people to repent and ask God for forgiveness from all kinds of immorality, abandon unjust behaviour, increase charity, and renounce hostility. Because of the prolonged drought that has hit this country could be a warning from Allah for our actions. Secondly, the MUI urges Muslims to perform Istisqa prayers (prayers for rain), preceded by fasting for 3 days, seeking for forgiveness (istighfar), polite behaviour and simple life. The Muslims were also asked to ask for prayer to be more pious, according to the Prophet Muhammad and his companions. And third, the MUI calls on the government to adopt a policy of strict and strategic measures that have implications for stopping or reducing damaging behaviour, given the adverse effects of a long drought, among others by enforcing laws that bind every arsonist and landowner that causes the danger of smoke,…

13

This memorandum was then followed up by the Muslims at the society, who conducted the

Istisqa prayer in the villages, where there was a long drought. In practice, people go out into the open to pray and pray

istisqa. Many areas conducted this prayer and eventually the raining was coming directly during they conducted prayer after months of drought and not raining.

14Because of the severity of the fires in 2015, which caused huge losses, the government of President Jokowi realized the importance of direct handling of the source of the problem of peat forest fires. Peat forest fires have repeatedly caused haze disasters, leading to protests from neighboring countries. Thus, at the beginning of his administration, President Joko Widodo established the Peat Restoration Agency with the ambition of restoring 2 million hectares of peatland in seven provinces, mainly those affected by peat forest fires. (

United Nation Development Program [UNDP] 2016). The Peatland Restoration Agency (BRG) was established by virtue of the Presidential Regulation No. 1 of 2016, signed by President Joko Widodo on 6 January 2016. BRG operates under and reports to the President. BRG is responsible for coordinating and facilitating, reporting to the President. It operates in seven priority provinces, namely Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, West Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan, South Kalimantan, and Papua. BRG’s target of peatland restoration is set to two million hectares, which must be accomplished within the working period, starting from 6 January 2016 to 31 December 2020 (

Badan Restorasi Gambut [BRG] 2019).

In its program, BRG takes comprehensive action in collaboration with various stakeholders. According to BRG, their institutions collaborate with seven regional governments, including the governments in Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, West Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan, South Kalimantan, and Papua provinces in completing the peatland restoration programs. The seven provinces are BRG’s priorities for the period of 2016–2020. Additionally, collaboration with 57 district or municipal governments in the seven provinces is also established. BRG, along with its partners, has facilitated 262 villages. The other efforts by BRG also strengthened the community group, up to 2018, they have engaged with 291 community groups to have organized freshwater fisheries, livestock farming, beekeeping, etc.

In 2016, the effort to prevent the burning the forest and land was requested in a letter by the Director General of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK), San Afri Awang, on 6 January 2016, who specifically requested a fatwa on the effort to prevent forest fires The Ministry of Environment and Forestry requested support to give endorsement that all Indonesian people carry out activities to prevent land and forest fires in Indonesia: because forest fires damage public health in a broad and uncontrolled way, and because forest fires place economic and social burdens on every affected person.

The next consideration requested was due to repeated land and forest fires every year that disrespected the right to healthy living for everyone. After a series of many meetings, MUI issued Fatwa No. 30/2016, concerning the Law on Forest and Land Burning (

Majelis Ulama Indonesia [MUI] 2016):

The burning of forests and land that can cause damage, pollution, harm to other persons, adverse health effects, and other harmful effects, is religiously forbidden (haram).

Facilitating, allowing, and/or deriving benefits from the burning of forests and land as referred to in item 1 is religiously forbidden (haram).

The issuance of this fatwa becomes an important motivation, that attempts to preserve the environment and as such has received wide attention. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry believes that efforts made by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, such as material law enforcement alone, are not enough and this Fatwa will bring important pressure from the moral side. Thus, the integration of approaches using religious fatwas can be an important part of efforts to tackle forest fires. This effort is also important because religious leaders are those who are respected in the community at the grassroots level (

Mangunjaya et al. 2018). Therefore, learning from the huge losses and fires, the government is making every effort to be proactive in efforts to prevent forest fires. However the effort to disseminate this fatwa becomes a challenge.

Socialization efforts were then carried out in several regions, and also partially carried out by the MUI together with related agencies. In addition, dissemination of the fatwa was carried out by the UNAS Center for Islamic Studies with BRG and MUI. The existence of the fatwa also encourages Muslims in particular to be more confident that they are carrying out land conservation as part of efforts to implement fatwas on the ground.

Although there has been no validation or research on whether this fatwa has an impact on reducing forest fires, at least the record of forest fires during the last three years after 2016 and efforts to implement this fatwa has been carried out, which has helped the community understand the prevention of burning land and forests. Abdul Rahim

15, a cleric who took part in this training in July 2018, stated that after his training, he spread the word regarding the fatwa through the mosque and the Muslim congregation (pengajian) to make “…the fatwa more informative to the villages that burning the land is prohibited by religion (haram) and to guard it are an obligation (wajib).”

Some research after 2015 shows a decrease in fire hotspots that occurred in Indonesia. Of course, this compliance effort is the result of integrated actions and policies, because dealing with forest fires is a complex problem and must be carried out with a multidisciplinary approach. No less important, in the face of forest and land fires, the government has acted more decisively. President Jokowi, gave the command so that the Commander-in-Chief (regional commander) deployed military troops, so that no fire could occur. In addition, the president will order the Chief of Police and Armed Forces Commander to move in his troops if they fail to put out fires in their area (

The Jakarta Post 2019).

In early August of 2019, when there were indications of a long dry season, President Jokowi gave instructions and gathered police chiefs and TNI commanders and instructed the Chief of Regional Police (Kapolda), Commander of the Kodam (Pangdam), Commander of Military Resort (Danrem), Commander of Kodim (Dandim) and the Head of the Resort Police (Kapolres) to work to help the Governor, Regent/Mayor and collaborate with the central government. To the Commander of the TNI, National Police Chief, BNPB, and BPB, Jokowi emphasized not to let the events get worse. The slightest fire must immediately be extinguished (

Ministry of Environment and Forestry [MOEF] 2019).

In this case, the moral support of the ulama in their efforts to prevent forest fires is very important and they are willing to help the government

16. In other words, this fatwa can be complementary to state regulations because it is increasingly clear that the legal status of forest burners is damaging and causing harm to humanity.

Panjaitan (

2018) noted a decrease in hotspots occurred during 2015–2017. Hotspots in 2015: 21,929 hotspots, to 2016: 3915 hotspots and in 2017: 2567 hotspots. In 2017, they were reduced (97%), the challenge then increased in 2018, to 4613.

Although it is clear that if the sentence is upheld, the sanctions stipulated by Law No. 41 of 1999 also Forestry (Article 78 paragraph 3) mean that perpetrators of forest fires are subject to 15 years of imprisonment and a maximum fine of Rp 5 billion. However, law enforcement is complex and expensive to implement. This paper is an illustration of the importance of involving Islamic religious leaders in participating in overcoming environmental challenges.

6. Conclusions

Islam still exists as an ongoing faith, because Muslims believe that the teachings of Islam must not only apply in the world but will be asked about in the hereafter. This belief is driving environmental action in Indonesia, and can be an entry into actions that are believed to change perceptions and behavior at the grassroots level. Nevertheless, religious elements are not the only element that can encourage the prevention of environmental damage; religious teachings such as this fatwa can be complementary to actions that are more environmentally friendly and care for nature, because changes and worldviews based on beliefs are the basis for changing behavior.

Substantially, there is no separation between aspects of religious beliefs and environmental care practices because Islam is inherently an environmental religion, e.g., the need for clean and good nature, such as uncontaminated ablution water for the legal (acceptance) of worship. There are indications when on the field that the fatwa can bring the Muslim community to a better understanding regarding the importance of nature conservation. Therefore, the approach through religion can be one of the important entries in making Muslim communities aware of environmental conservation.

Fatwas issued by MUI, as an institution that has the authority to provide answers to religious teachings to Muslims, especially in Indonesia, may become a model for other Muslims elsewhere who want the response of religious teachings to become guidelines on aspects of morality common to people and nations still also affected by the care of nature and its contents.