A Universal Parameter to Predict Subaerial Landslide Tsunamis?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

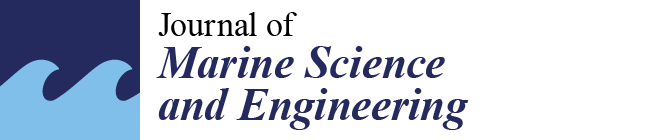

2. The Impulse Product Parameter

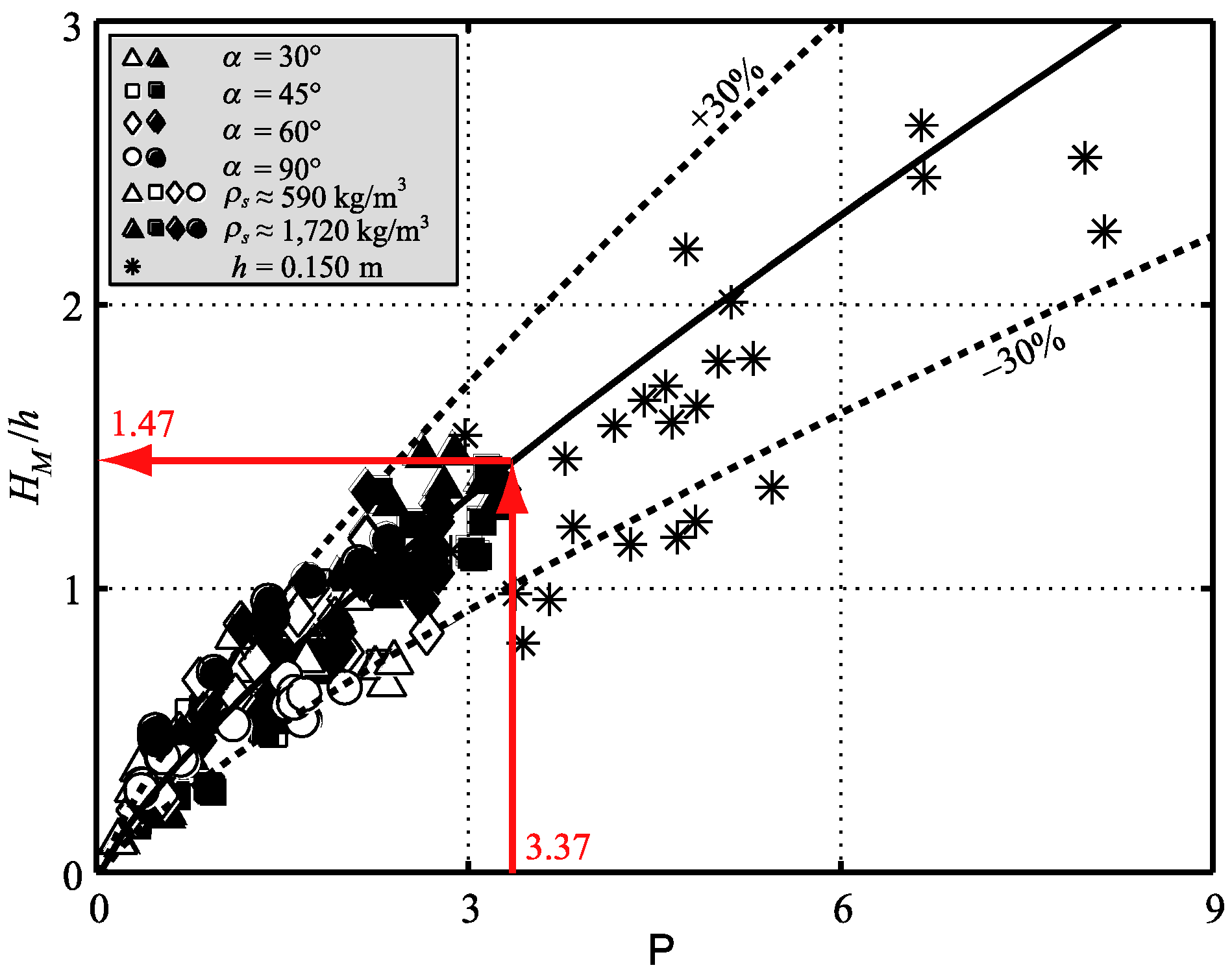

2.1. Derivation

, with bulk slide volume

, with bulk slide volume  , was with ρs1/4 found to be less pronounced in the data analysis than predicted in Equation (2).

, was with ρs1/4 found to be less pronounced in the data analysis than predicted in Equation (2).

/(sbs)]/Vs} (0.34 − 1.00) considering the transition type are relevant, with ts = characteristic time of submerged landslide motion.

/(sbs)]/Vs} (0.34 − 1.00) considering the transition type are relevant, with ts = characteristic time of submerged landslide motion.

| Wave parameter | Heller and Hager [26] | Heller and Spinneken [29] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slide type | granular | block | ||

| Maximum amplitude | aM = (4/9)P4/5h | (R2 = 0.88) | aM = (3/4)[PBΦTs1/2]9/1°h | (R2 = 0.88) |

| Streamwise distance at aM | xM = (11/2)P1/2h | (R2 = 0.23) | − | − |

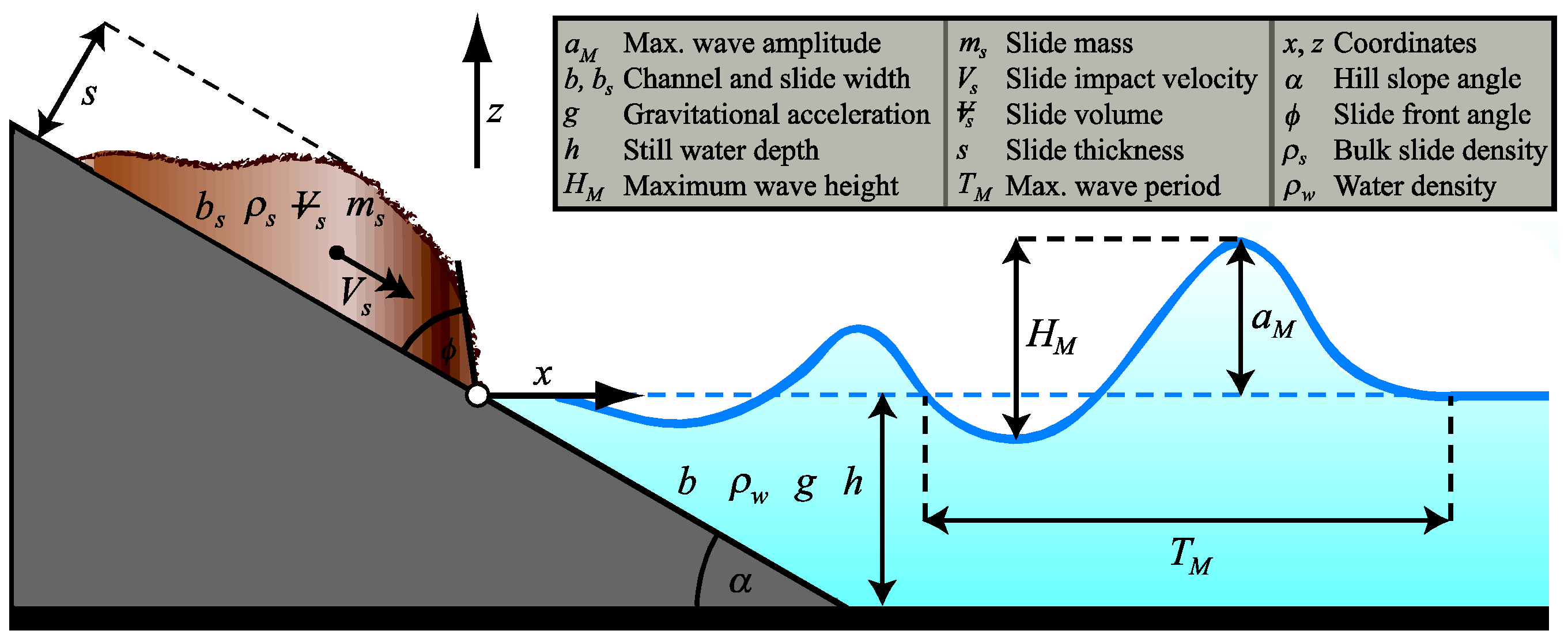

| Maximum height (Figure 2) | HM = (5/9)P4/5h | (R2 = 0.82) | HM = [PBΦTs1/4]9/1°h | (R2 = 0.93) |

| Maximum period | TM = 9P1/2(h/g)1/2 | (R2 = 0.33) | TM = (19/2)[PTs1/2]1/4(h/g)1/2 | (R2 = 0.24) |

| Amplitude evolution | a(x) = (3/5)[P(x/h)−1/3]4/5h | (R2 = 0.81) | a(x) = (11/10)[P(x/h)−1/3BΦTs3/4]9/1°h | (R2 = 0.85) |

| Height evolution | H(x) = (3/4)[P(x/h)−1/3]4/5h | (R2 = 0.80) | H(x) = (3/2)[P(x/h)−1/3BΦTs1/2]9/1°h | (R2 = 0.89) |

| Period evolution | T(x) = 9[P(x/h)5/4]1/4(h/g)1/2 | (R2 = 0.66) | T(x) = (13/2)[P(x/h)5/4Ts1/3]1/4(h/g)1/2 | (R2 = 0.53) |

2.2. Analytical Aspects

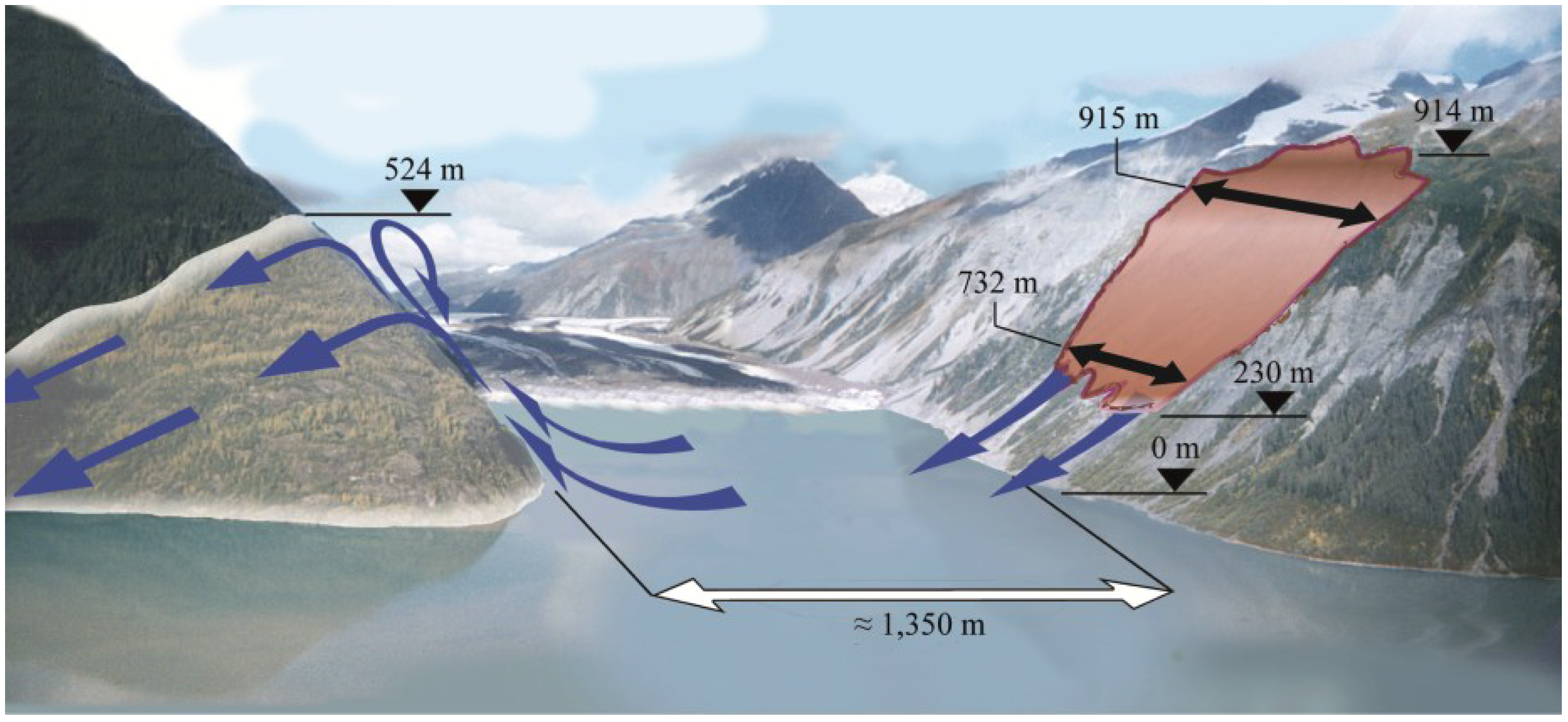

3. Real-World Applications

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Experimental Methodology

| Name | Symbol | Dimension | Heller and Hager [26] | Heller and Spinneken [29] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slide model type | − | − | granular | block |

| Channel width | b | (m) | 0.500 | 0.600 |

| Still water depth | h | (m) | 0.150–0.675 | 0.300, 0.600 |

| Slide thickness | s | (m) | 0.050–0.249 | 0.120 |

| Grain diameter | dg | (mm) | 2.0–8.0 | − |

| Streamwise distance | x | (m) | 0–8.90 | 0–17.7 |

| Slide impact velocity | Vs | (m/s) | 2.06–8.77 | 0.59–3.56 |

| Bulk slide volume |  | (m3) | 0.0167–0.0668 | 0.0373 |

| Bulk slide density | ρs | (kg/m3) | 590–1,720 | 1,534 |

| Slide mass | ms | (kg) | 10.09–113.30 | 57.23 |

| Slide width | bs | (m) | 0.500 | ~0.588, ~0.578, 0.526 |

| Slide front angle | φ | (°) | not systematic investigated | 30, 45, 60, 90 |

| Transition type | − | (−) | none | none and circular shaped |

| Hill slope angle | α | (°) | 30–90 | 45 |

| Slide Froude number | F | (−) | 0.86–6.83 | 0.34–2.07 |

| Relative slide thickness | S | (−) | 0.09–1.64 | 0.20–0.40 |

| Relative slide mass | M | (−) | 0.11–10.02 | 0.27–1.21 |

| Relative streamwise distance | x/h | (−) | 0–59 | 0–40 |

| Impulse product parameter | P | (−) | 0.17–8.13 | 0.16–1.19 |

| Number of tests | i | (−) | 434 | 144 |

References

- Miller, D.J. Giant Waves in Lituya Bay, Alaska; Geological Survey Professional Paper No. 354-C; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1960.

- Slingerland, R.L.; Voight, B. Occurrences, properties and predictive models of landslide-generated impulse waves. In Rockslides and Avalanches; Voight, B., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1979; Volume 2, pp. 317–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, S.N. Landslide tsunami. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 11201–11215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synolakis, C.E.; Bardet, J.-P.; Borrero, J.C.; Davies, H.L.; Okal, E.A.; Silver, E.A.; Sweet, S.; Tappin, D.R. The slump origin of the 1998 Papua New Guinea Tsunami. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 2002, 458, 763–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, D.G.; Harbitz, C.B.; Wynn, R.B.; Pedersen, G.; Løvholt, F. Submarine landslides: Processes, triggers and hazard prediction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2006, 364, 2009–2039. [Google Scholar]

- WCHL. Hydraulic Model Studies—Wave Action Generated by Slides into Mica Reservoir—British Columbia. Report; Western Canada Hydraulic Laboratories: Vancouver, Canada, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Løvholt, F.; Pedersen, G.; Gisler, G. Oceanic propagation of a potential tsunami from the La Palma Island. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113, C09026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, H.; Boes, R. Berechnung felsrutschinduzierter Impulswellen im Vierwaldstättersee. Wasser Energ. Luft 2010, 102, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, S.F.L.; Talling, P.J.; Vardy, M.E.; Heller, V.; Hühnerbach, V.; Urlaub, M.; Sarkar, S.; Masson, D.G.; Henstock, T.J.; Minshull, T.A.; et al. Combinations of volcanic-flank and seafloor-sediment failure offshore Montserrat, and their implications for tsunami generation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2012, 319–320, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, K.; Simpson, G.; Girardclos, S. Giant Lake Geneva tsunami in AD 563. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 756–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.N.; Day, S. Ritter Island Volcano—Lateral collapse and the tsunami of 1888. Geophys. J. Int. 2003, 154, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, J.J.; Kos, A.; Issa, N. Fluid motion generated by impact. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2003, 129, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quecedo, M.; Pastor, M.; Herreros, M.I. Numerical modeling of impulse wave generated by fast landslides. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2004, 59, 1633–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.L.-F.; Wu, T.-R.; Raichlen, F.; Synolakis, C.E.; Borrero, J.C. Runup and rundown generated by three-dimensional sliding masses. J. Fluid Mech. 2005, 536, 107–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynett, P.; Liu, P.L.-F. A numerical study of the run-up generated by three-dimensional landslides. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, C03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, H.F.; Higman, B. Lagrangian hydrocode simulations of the 1958 Lituya Bay tsunamigenic rockslide. Geochem. Geophy. Geosyst. 2007, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bascarini, C. Computational fluid dynamics modelling of landslide generated water waves. Landslides 2010, 7, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, S.M.; Morichon, D.; Grilli, S.; Glockner, S. Numerical simulation of waves generated by landslides using a multiple-fluid Navier-Stokes model. Coast. Eng. 2010, 57, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, S.M.; Harris, J.C.; Grilli, S.T.; Fabre, R. Numerical modeling of tsunami waves generated by the flank collapse of the Cumbre Viejo Volcano (La Palma, Canary Islands): Tsunami source and near field effects. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, C05030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Hager, W.H. Forecasting impulse waves in reservoirs. In Proceedings of 19th Congrès des Grands Barrages, Florence, Italy, 26–30 May 1997; pp. 993–1005.

- Walder, J.S.; Watts, P.; Sorensen, O.E.; Janssen, K. Tsunamis generated by subaerial mass flows. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H.M.; Hager, W.H.; Minor, H.-E. Near field characteristics of landslide generated impulse waves. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2004, 130, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizzo, A.; De Girolamo, P.; Petaccia, A. Forecasting impulse waves generated by subaerial landslides. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110, C12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweifel, A.; Hager, W.H.; Minor, H.-E. Plane impulse waves in reservoirs. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2006, 132, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enet, F.; Grilli, S.T. Experimental study of tsunami generation by three-dimensional rigid underwater landslides. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2007, 133, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, V.; Hager, W.H. Impulse product parameter in landslide generated impulse waves. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2010, 136, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, V.; Hager, W.H. Wave types of landslide generated impulse waves. Ocean Eng. 2011, 38, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, F.; Fritz, H.M. Physical modeling of tsunamis generated by three-dimensional deformable granular landslides. J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, C11015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, V.; Spinneken, J. Improved landslide-tsunami predictions: Effects of block model parameters and slide model. J. Geophys. Res. 2013, 118, 1489–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, H.J. Reichweite und Geschwindigkeit von Bergstürzen und Fliessschneelawinen. Rock Mech. 1976, 8, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, V.; Hager, W.H.; Minor, H.-E. Landslide generated impulse waves in reservoirs—Basics and computation. In VAW-Mitteilung 211; Boes, R., Ed.; Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, H.; Pfister, M.; Boes, R.; Perzlmaier, S.; Reindl, R. Impulswellen infolge Lawineneinstoss in den Speicher Kühtai. Wasserwirtschaft 2011, 101, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cannata, M.; Marzocchi, R.; Molinari, M.E. Modeling of landslide-generated tsunamis with GRASS. Trans. GIS 2012, 16, 191–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, H.; Winz, E.; Hager, W.H. Underwater landslide characteristics from 2D laboratory modeling. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2013, 139, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, I.J.; Montgomery, D.R. Landslide erosion coupled to tectonics and river incision. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, H.M.; Hager, W.H.; Minor, H.-E. Lituya Bay case: Rockslide impact and wave run-up. Sci. Tsunami Hazards 2001, 19, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.V.; Watts, G.M. Laboratory Investigation of the Vertical Rise of Solitary Wave on Impermeable Slopes; Technical Memo Report No. 33; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Beach Erosion Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1953.

- BGC. Mitchell Pit Landslide Generated Wave Modelling. Appendix 4-E; BGC Engineering Inc.: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, P. Tsunami features of solid block underwater landslide. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2000, 126, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bardet, J.-P.; Synolakis, C.E.; Davies, H.L.; Imamura, F.; Okal, E.A. Landslide tsunamis: Recent findings and research directions. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2003, 160, 1793–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi-Jilani, A.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B. Estimation of near-field characteristics of tsunami generation by submarine landslide. Ocean Eng. 2008, 35, 545–557. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, V.; Moalemi, M.; Kinnear, R.D.; Adams, R.A. Geometrical effects on landslide-generated tsunamis. J. Waterw. Port C-ASCE 2012, 138, 286–298. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, V.; Hager, W.H.; Minor, H.-E. Scale effects in subaerial landslide generated impulse waves. Exp. Fluids 2008, 44, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, R.G.; Häusler, G.; Herrmann, J.M. Laser triangulation: Fundamental uncertainty in distance measurement. Appl. Opt. 1994, 33, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, M.; Willert, C.E.; Kompenhans, J. Particle Image Velocimetry—A Practical Guide; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Heller, V.; Hager, W.H. A Universal Parameter to Predict Subaerial Landslide Tsunamis? J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2, 400-412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse2020400

Heller V, Hager WH. A Universal Parameter to Predict Subaerial Landslide Tsunamis? Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2014; 2(2):400-412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse2020400

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeller, Valentin, and Willi H. Hager. 2014. "A Universal Parameter to Predict Subaerial Landslide Tsunamis?" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2, no. 2: 400-412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse2020400

APA StyleHeller, V., & Hager, W. H. (2014). A Universal Parameter to Predict Subaerial Landslide Tsunamis? Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2(2), 400-412. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse2020400