A Multicomponent OBN Time-Shift Joint Correction Method Based on P-Wave Empirical Green’s Functions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Data

2.2. Preprocessing

3. Methods and Technical Workflow

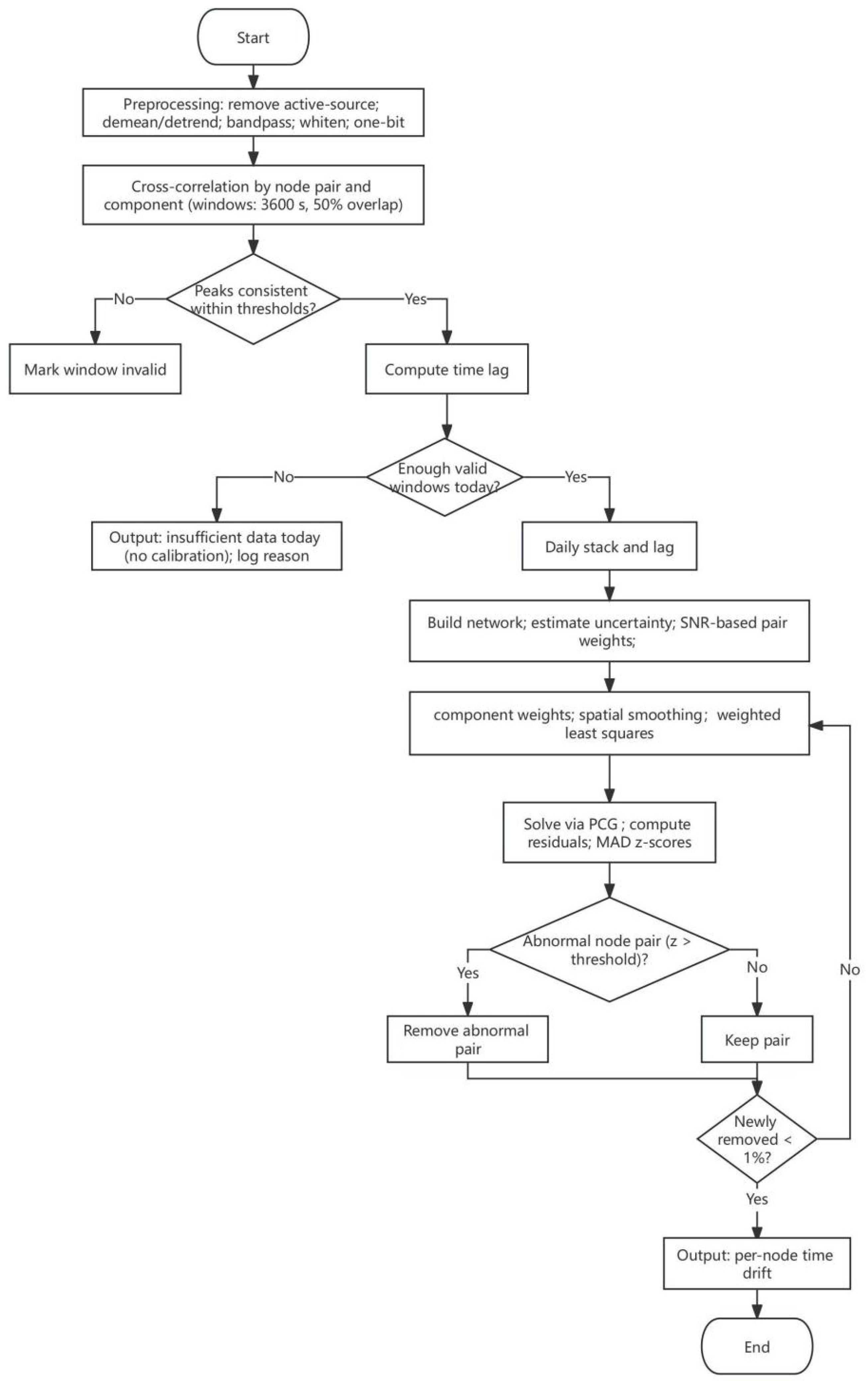

3.1. Technical Workflow

- (1)

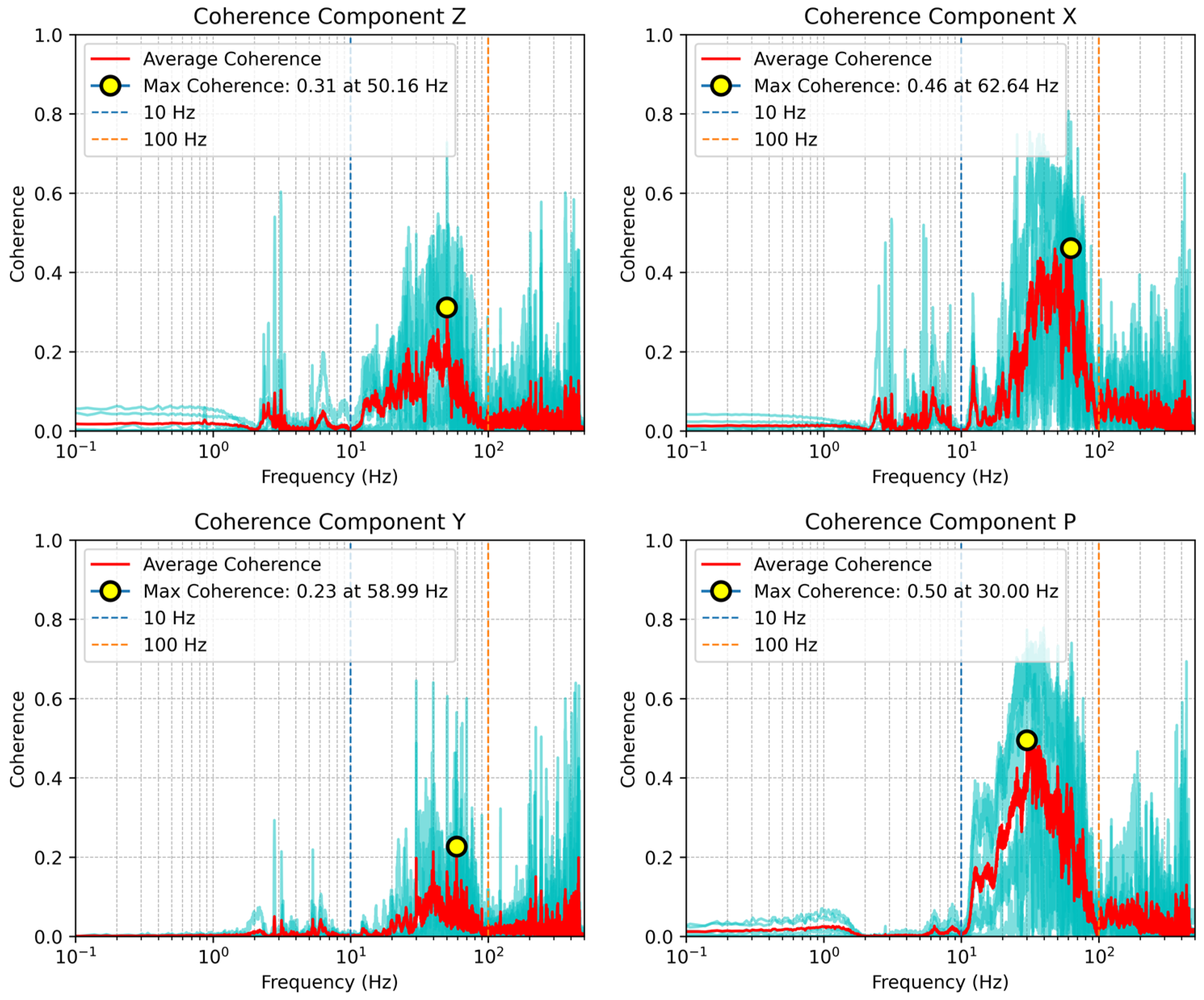

- Remove the mean and trend from seismic records; apply band-pass filtering between 10 and 100 Hz (as determined from PSD–coherence analysis); perform spectral whitening and one-bit normalization.

- (2)

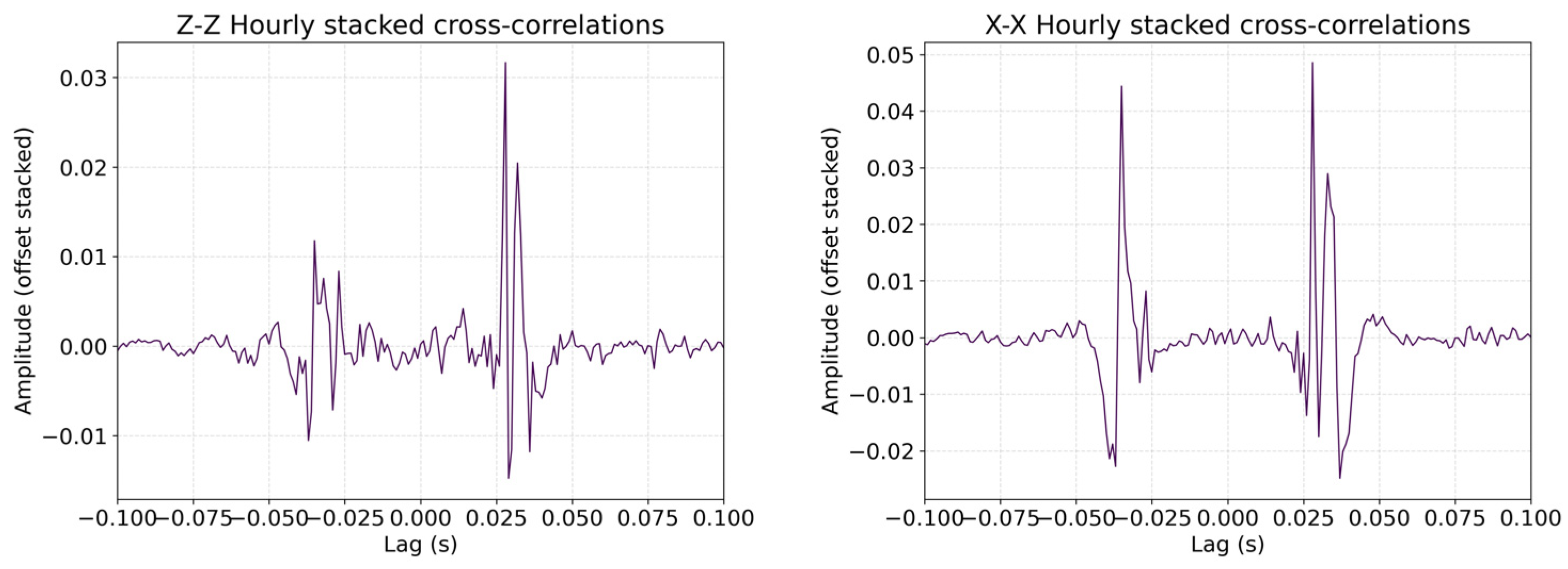

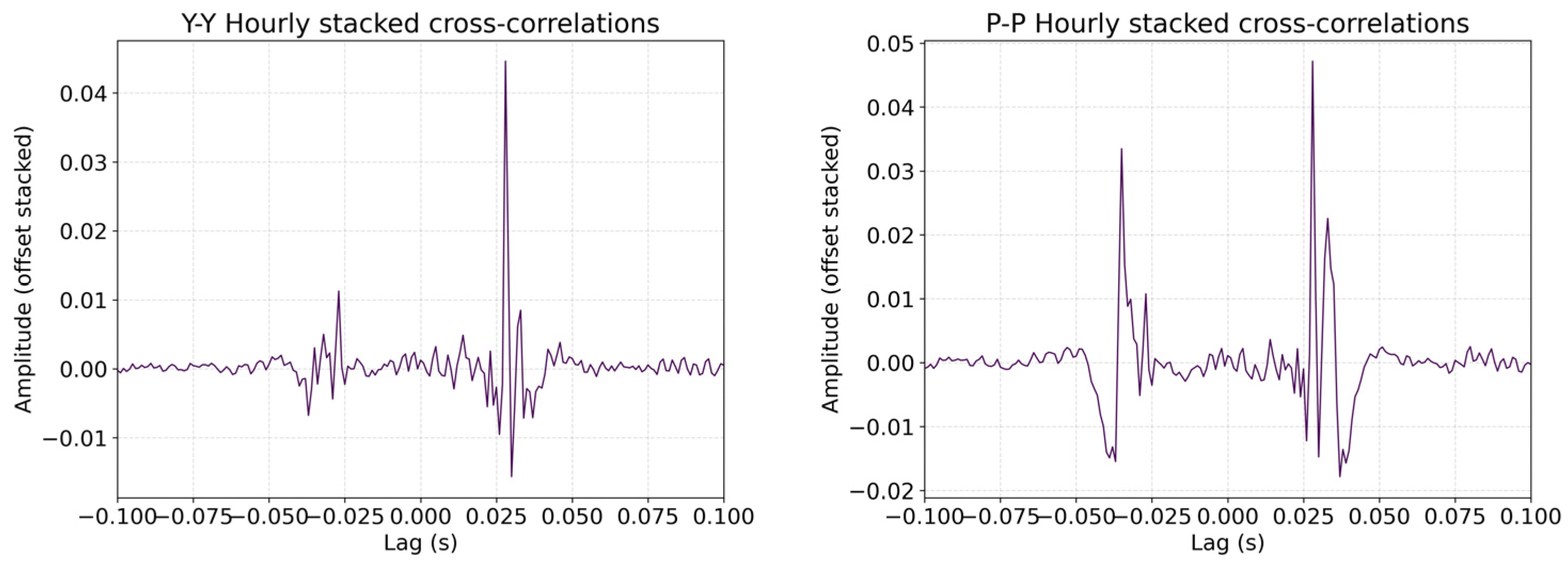

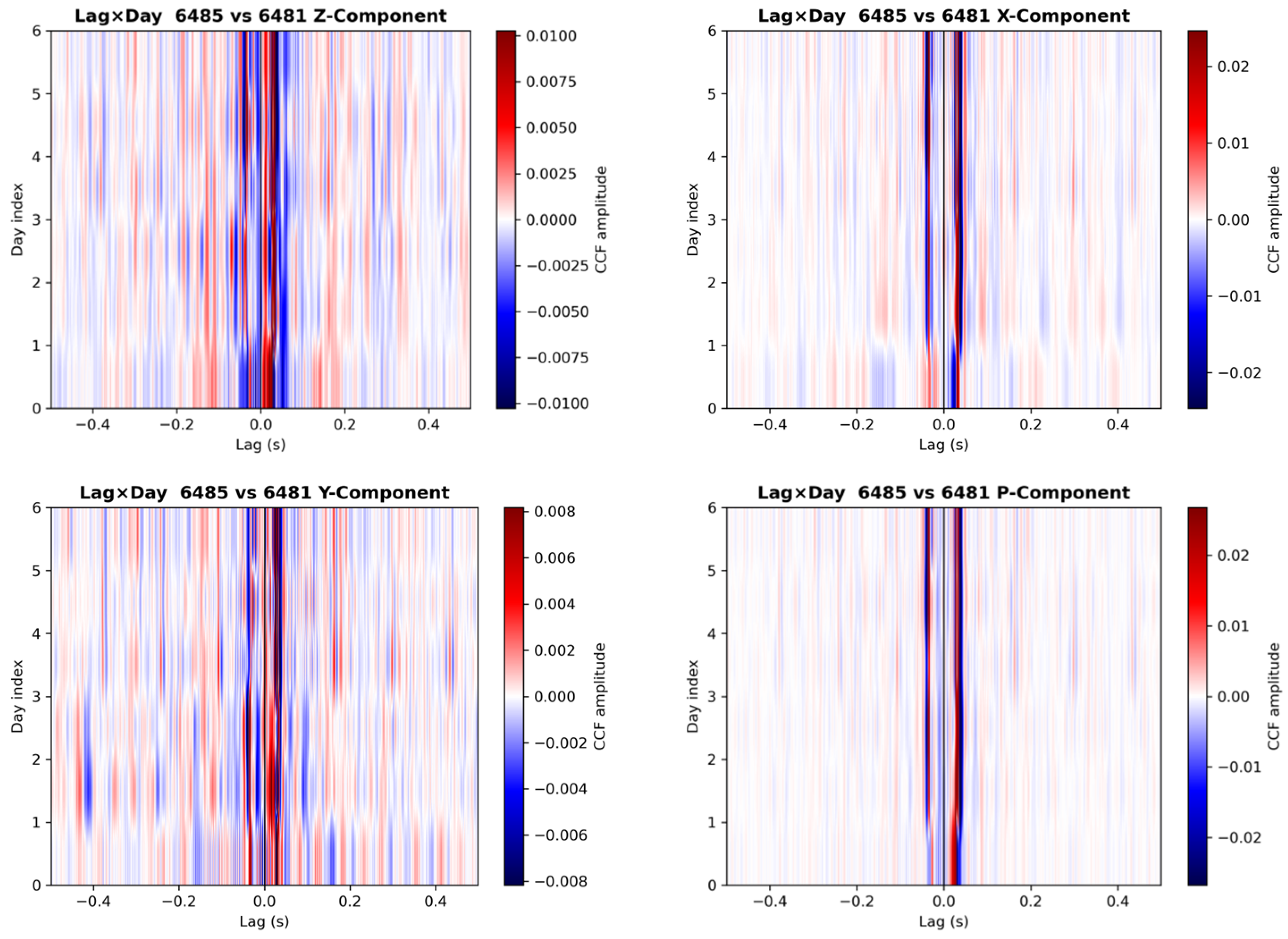

- Segment daily data into 3600 s windows with 50% overlap; for each window and each component, compute cross-correlations between adjacent node pairs and extract the time delays of the dominant peaks on both positive and negative branches.

- (3)

- If the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the branch peak fails to meet the criterion in Equation (1), that branch is deemed invalid; if the number of valid windows for a given day falls below the threshold, the day is regarded as invalid. The remaining valid windows are stacked to obtain the daily empirical Green’s function (EGF) and the observed P-wave time-delay difference.

- (4)

- Aggregate all valid adjacent node pairs of the day to form a system of observation equations; assign component weights according to SNR; construct second-order difference operators for each survey segment. Formulate the joint objective function and solve for the daily nodal time shifts using the preconditioned conjugate gradient method.

- (5)

- Outlier elimination is performed iteratively using a median-absolute-deviation (MAD)-based scale estimator and a z-score criterion; when the fraction of newly detected abnormal observations remains below 1% for two successive iterations, convergence is considered achieved and the iteration is terminated. If a continuous segment contains k consecutive invalid adjacent node pairs, or if the proportion of valid pairs falls below q%, the temporal continuity regularization term is strengthened to stabilize the solution. The overall technical workflow is illustrated in Figure 6.

3.2. Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.2. Discussion

- (1)

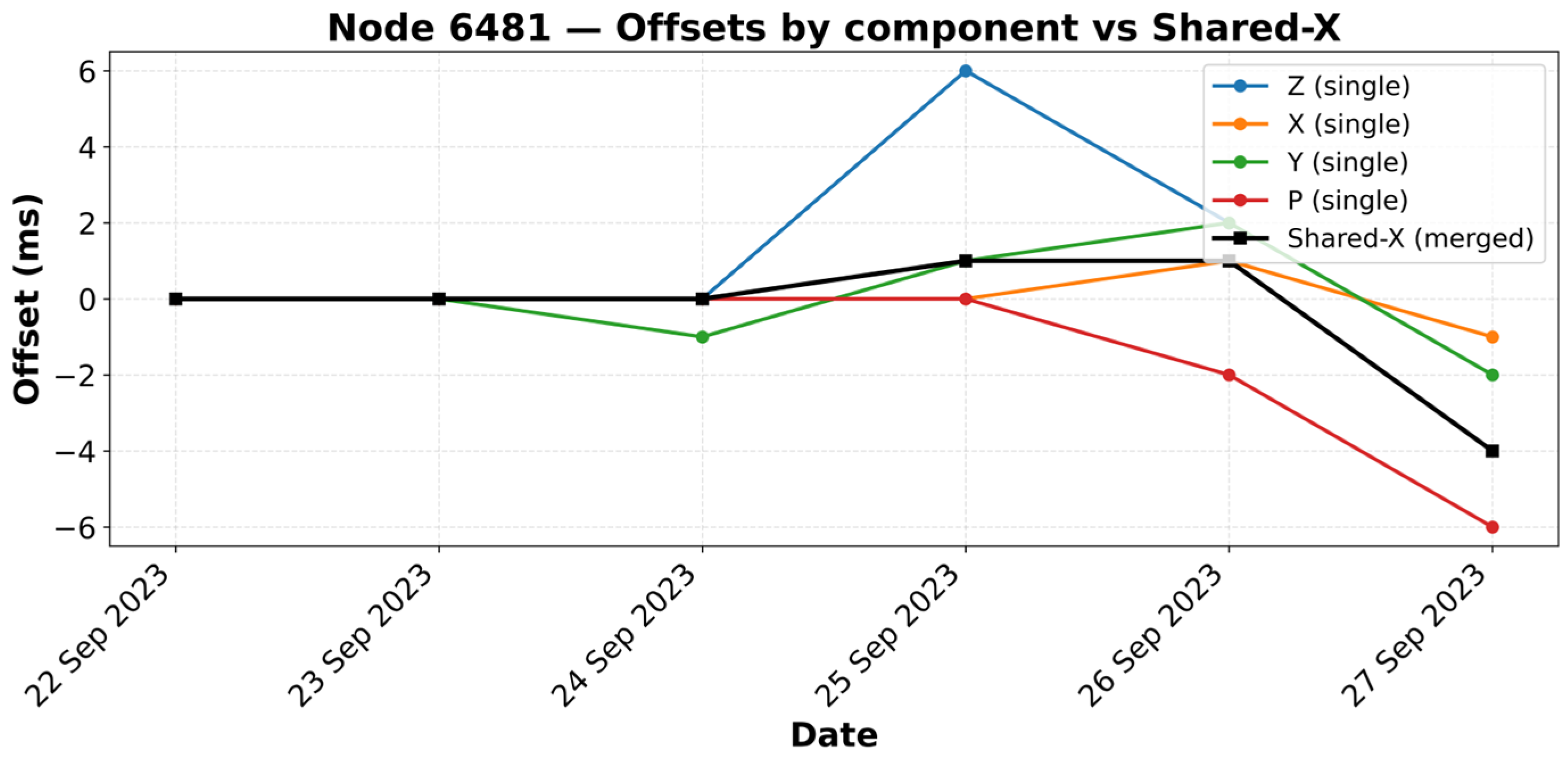

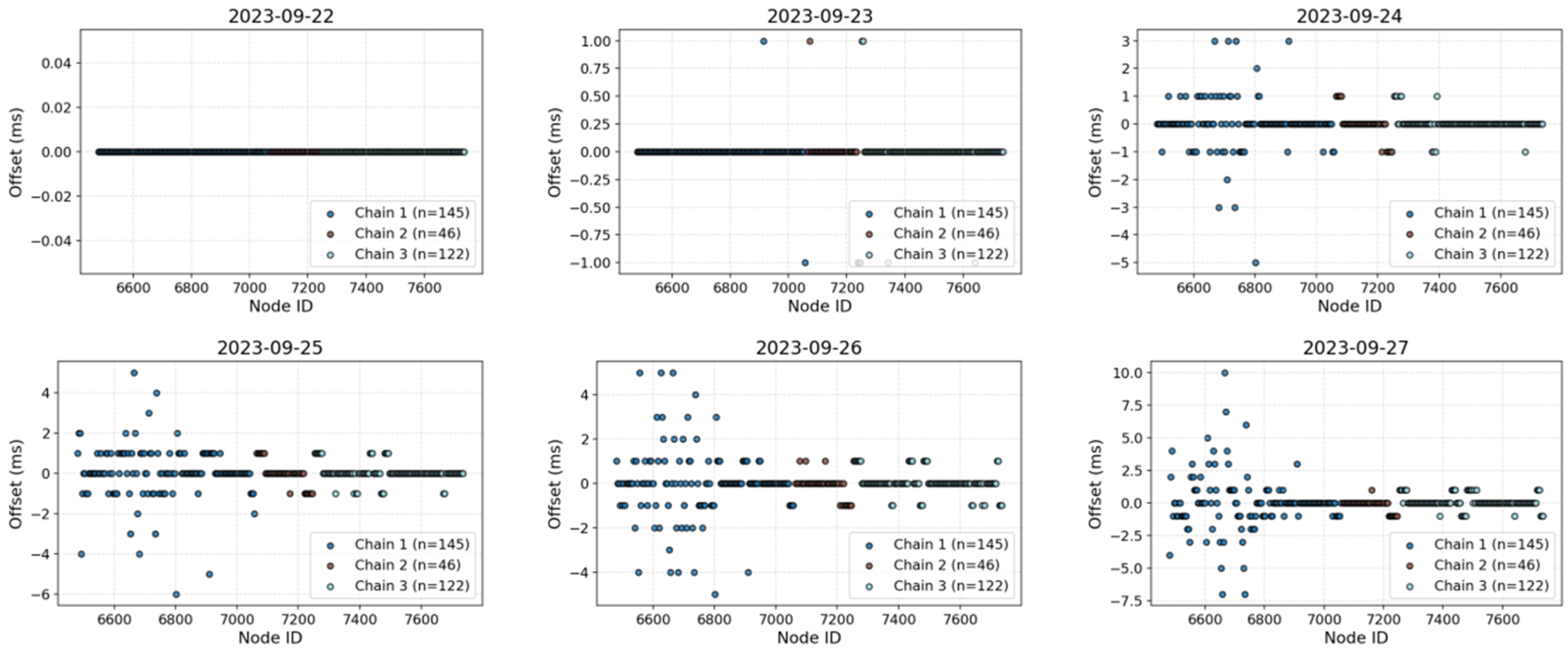

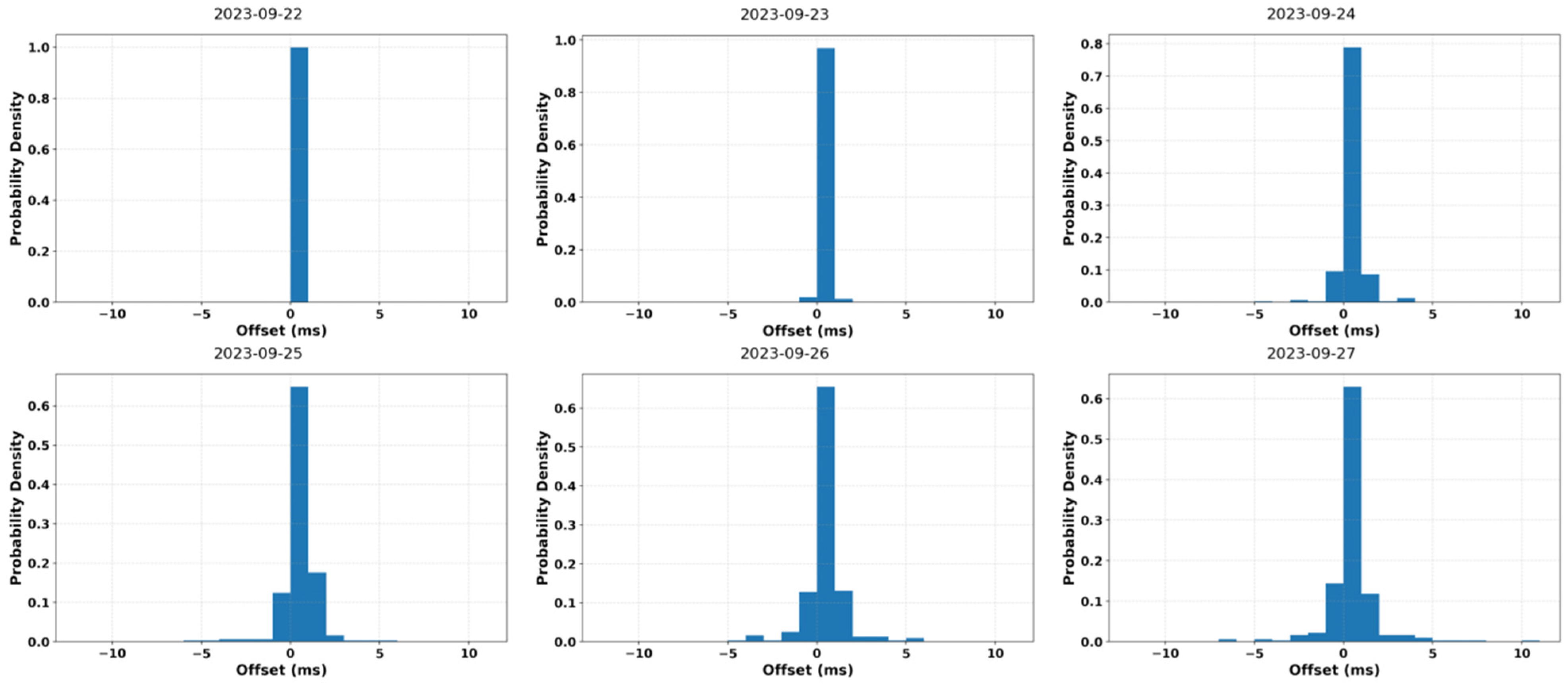

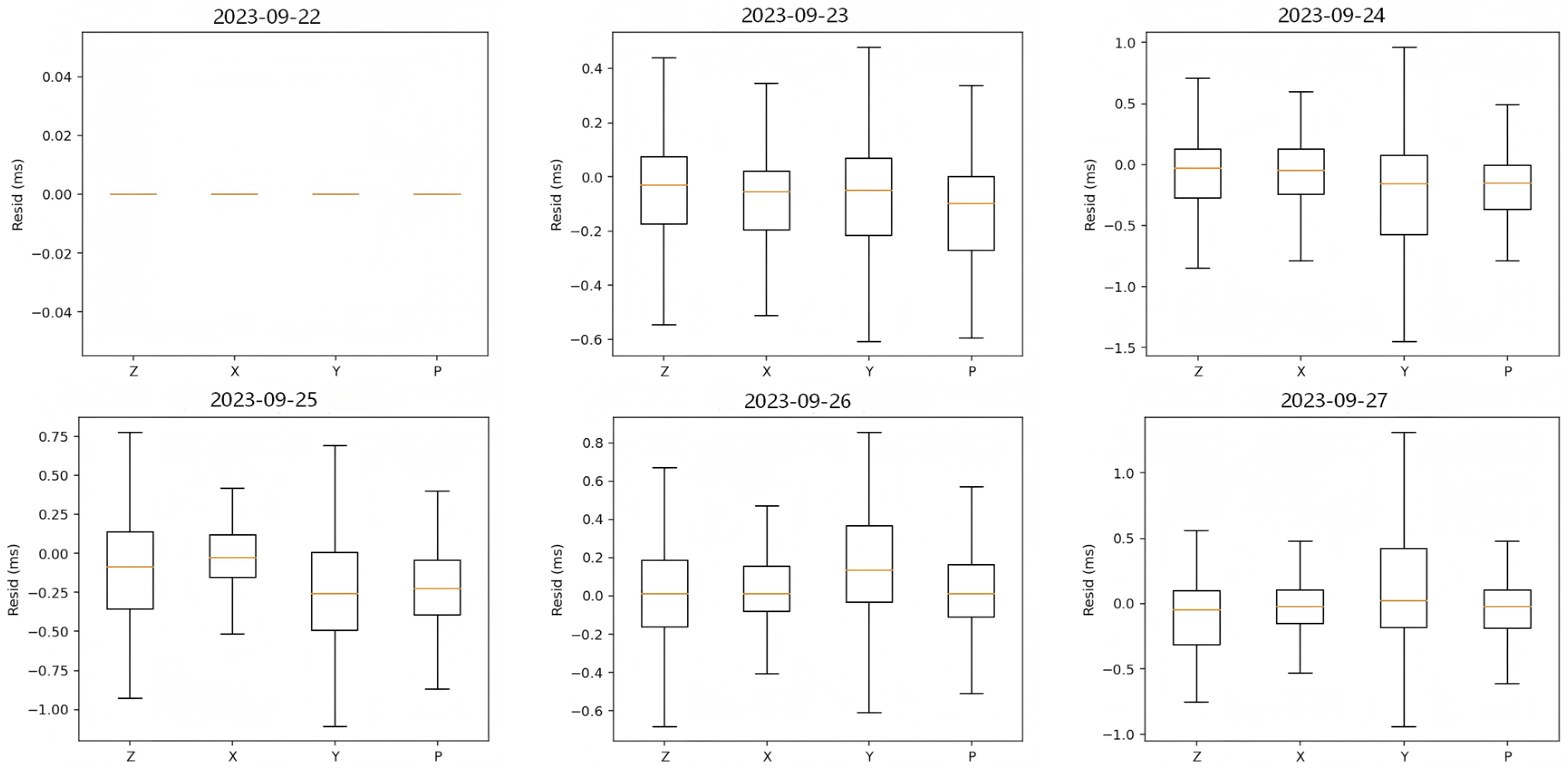

- Node-wise and array-wise drift behavior. Across 315 nodes over six days, daily drifts stay centered near 0 ms for ≥90% of nodes (≈±1–2 ms), but a subset shows gradual growth to 7–10 ms by day six—behavior that the method captures without over-smoothing. For a representative node (6481), single-component outliers (e.g., Z: +6 ms, P: −6 ms on particular days) are attenuated in the four-component fused solution, demonstrating the benefit of component fusion for robustness.

- (2)

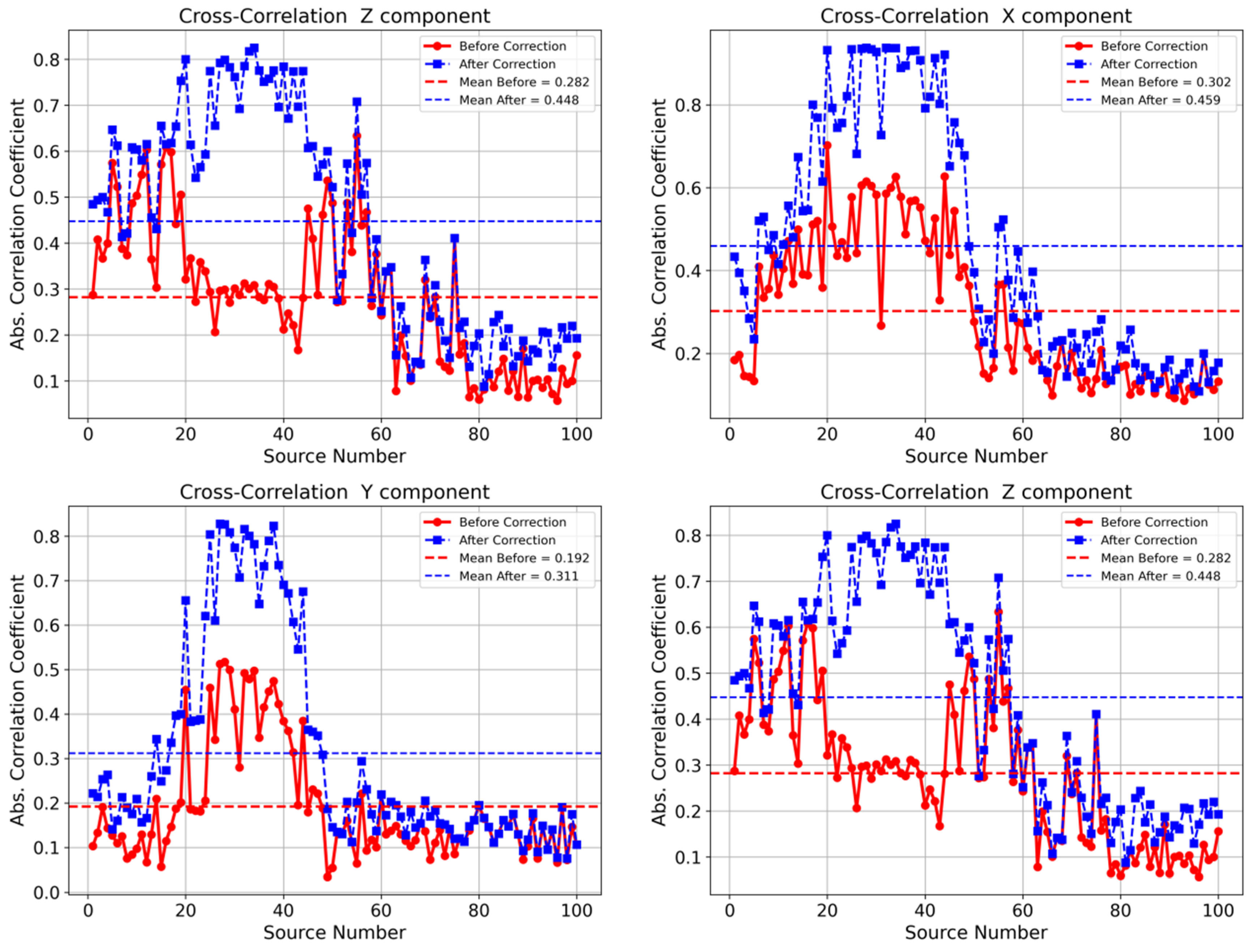

- Shot-gather correlation uplift. After applying fixed ms-level timing corrections implied by the inversion, cross-component correlation increases by about +0.12–+0.19 on average, with some shots improving by ≈+0.6, directly linking the time-shift solution to phase-alignment gains in active-source data.

- (1)

- Temporal scope. The evaluation covers six consecutive days; longer deployments may exhibit drift nonlinearity and step changes beyond those observed here, even after linear pre-correction.

- (2)

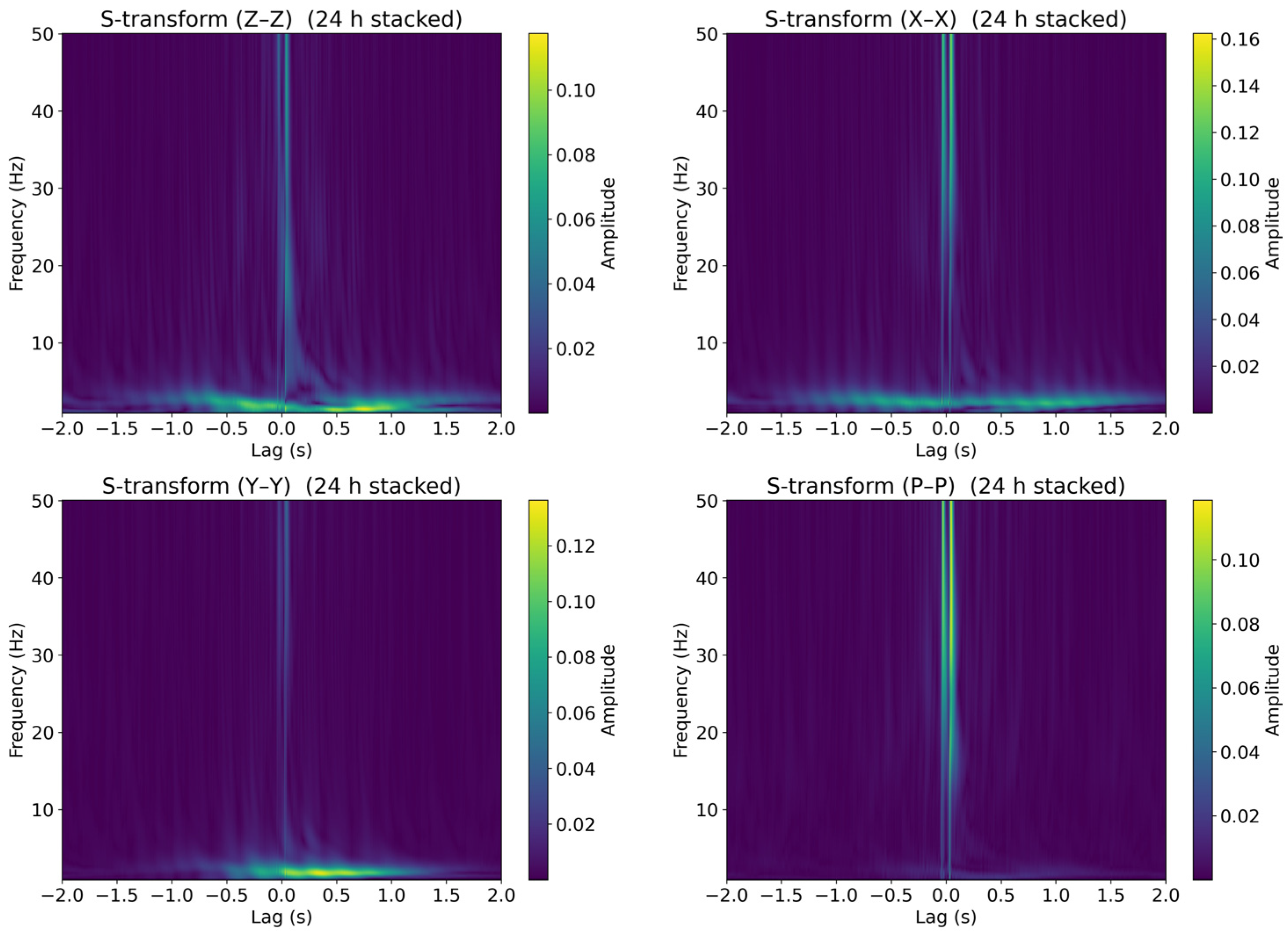

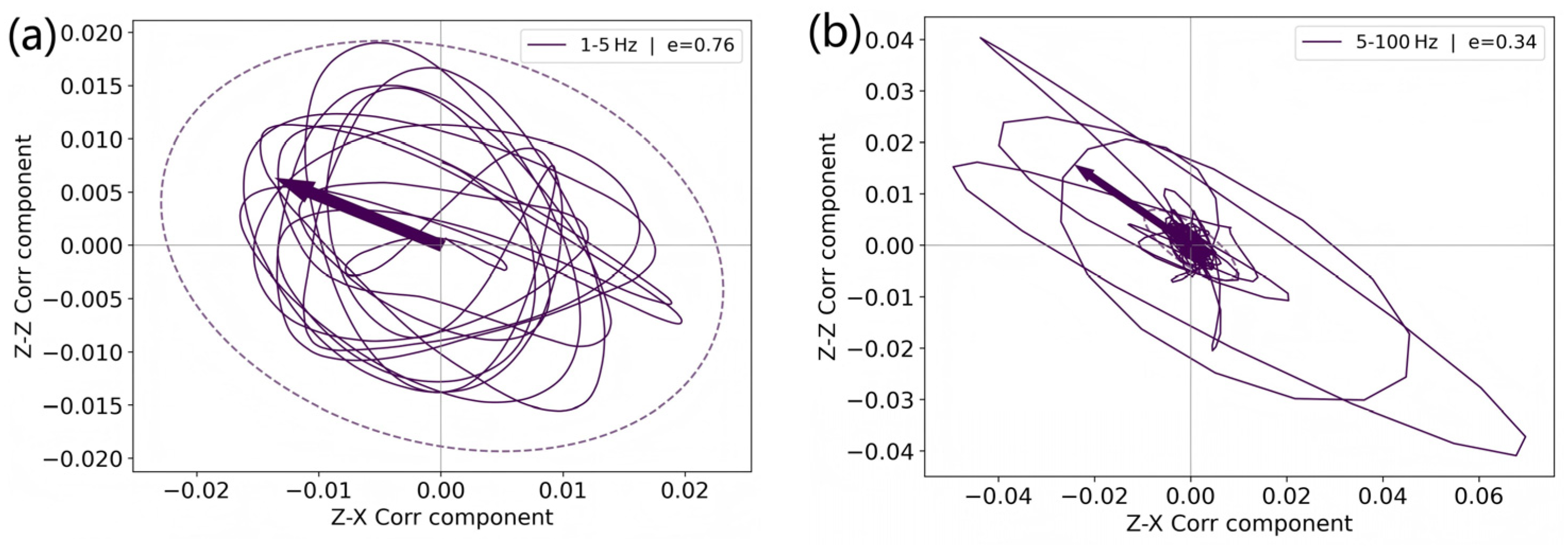

- Geometry and site specificity. The success of P-wave EGFs hinges on short inter-node spacing and the presence of a repeatable, narrow P arrival in ambient data; larger spacings or different seabed/ambient regimes may reduce P-wave SNR and alter optimal bands (10–100 Hz here).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Geng, J.; You, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hao, T.; Yao, Z. Separating Scholte Wave and Body Wave in OBN Data Using Wave-Equation Migration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5914213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Saygin, E. 3-D S Wave Imaging via Robust Neural Network Interpolation of 2-D Profiles From Wave-Equation Dispersion Inversion of Seismic Ambient Noise. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB024663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.J.; Shragge, J.; Danilouchkine, M.; Udengaard, C.; Gerritsen, S. Observations from the Seafloor: Ultra-Low-Frequency Ambient Ocean-Bottom Nodal Seismology at the Amendment Field. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 239, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Huang, Z.-L. Joint Reverse-Time Imaging Condition of Seismic Towed-Streamer and OBN Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 3007305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Shi, X.; Mao, W.; Alkhalifah, T.A.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Elastic Seismic Imaging Enhancement of Sparse 4C Ocean-Bottom Node Data Using Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5910214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y. Nonstationary Adaptive S-Wave Leakage Suppression of Ocean-Bottom Node Data. Geophysics 2024, 89, V605–V618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Du, Q.; Lv, W.; Wu, W.; Moser, T.J. Vector Decoupling-Based Elastic Reverse Time Migration for OBN Data in VTI Media. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5921410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.L.E.F.; Costa, F.T.; Karsou, A.; de Souza, A.; Capuzzo, F.; Moreira, R.M.; Lopez, J.; Cetale, M. Refraction FWI of a Circular Shot OBN Acquisition in the Brazilian Presalt Region. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5920518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, A.T.; Collins, J.A. Advancements in High-Performance Timing for Long Term Underwater Experiments: A Comparison of Chip Scale Atomic Clocks to Traditional Microprocessor-Compensated Crystal Oscillators. In Proceedings of the 2012 Oceans, Hampton Roads, VA, USA, 14–19 October 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, W.H.; Matias, L.; Stich, D.; Carrilho, F.; Jokat, W.; Monna, S.; IbenBrahim, A.; Mancilla, F.; Gutscher, M.-A.; Sallarès, V.; et al. Focal Mechanisms for Sub-Crustal Earthquakes in the Gulf of Cadiz from a Dense OBS Deployment. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L18309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzouz, O.; Pinheiro, L.; Herold, D. Correction of Ocean-Bottom Seismometer Random Clock Drift Artifacts. In Proceedings of the Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SEG) Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–23 October 2015; pp. 5634–5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeo, A.; Forsyth, D.W.; Weeraratne, D.S.; Nishida, K. Estimation of Azimuthal Anisotropy in the NW Pacific from Seismic Ambient Noise in Seafloor Records. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 199, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hable, S.; Sigloch, K.; Barruol, G.; Stähler, S.C.; Hadziioannou, C. Clock Errors in Land and Ocean Bottom Seismograms: High-Accuracy Estimates from Multiple-Component Noise Cross-Correlations. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 214, 2014–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loviknes, K.; Jeddi, Z.; Ottemöller, L.; Barreyre, T. When Clocks Are Not Working: OBS Time Correction. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2020, 91, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, B.; Woje, G. Ensuring Correct Clock Timing in Ocean Bottom Node Acquisition. In Proceedings of the SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting, Denver, CO, Canada, 1 January 2010; pp. 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, B.S.; Liu, Z.; Udengaard, C. Stabilizing Two-Term Clock-Drift Inversion in Ocean-Bottom Node Processing. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Meeting for Applied Geoscience & Energy, Houston, TX, USA, 17–20 August 2024; pp. 2696–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, W.; Zhao, M.H.; Qiu, X.L.; Li, J.B.; Ruan, A.G.; Li, S.J.; Zhang, J.Z. The Correction of Shot and OBS Position in the 3D Seismic Experiment of the SW Indian Ocean Ridge. Chin. J. Geophys. 2010, 53, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sens-Schönfelder, C. Synchronizing Seismic Networks with Ambient Noise. Geophys. J. Int. 2008, 174, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannemann, K.; Krüger, F.; Dahm, T. Measuring of Clock Drift Rates and Static Time Offsets of Ocean Bottom Stations by Means of Ambient Noise. Geophys. J. Int. 2014, 196, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouédard, P.; Seher, T.; McGuire, J.J.; Collins, J.A.; van der Hilst, R.D. Correction of Ocean-Bottom Seismometer Instrumental Clock Errors Using Ambient Seismic Noise. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2014, 104, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Su, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Qin, L. Deep Underground Observation of Rotational Motions Induced by M6.1 Hualien Earthquake. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 7509205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, G.; Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Jian, Y.; Wang, C. Deep Underground Observation Comparison of Rotational Seismometers. Chin. J. Geophys. 2022, 65, 4569–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weemstra, C.; de Laat, J.I.; Verdel, A.; Smets, P. Systematic Recovery of Instrumental Timing and Phase Errors Using Interferometric Surface-Waves Retrieved from Large-N Seismic Arrays. Geophys. J. Int. 2021, 224, 1028–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; Yao, Y.; Qiu, X. Analysis of Clock Drift Based on a Three-Dimensional Controlled-Source Ocean Bottom Seismometer Experiment. Geophys. Prospect. 2023, 72, 1312–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Zhu, G.; Zi, J.; Chen, H.; Yang, H. Evaluating and Correcting Short-Term Clock Drift in Data from Temporary Seismic Deployments. Earthq. Res. Adv. 2023, 3, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabieces, R.; Harris, K.; Ferreira, A.M.G.; Tsekhmistrenko, M.; Hicks, S.P.; Krüger, F.; Hannemann, K.; Schmidt-Aursch, M.C. Clock Drift Corrections for Large Aperture Ocean Bottom Seismometer Arrays: Application to the UPFLOW Array in the Mid-Atlantic Ocean. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 239, 1709–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, D.; Parisi, L.; Jónsson, S.; Jousset, P.; Werthmüller, D.; Weemstra, C. Ocean Bottom Seismometer Clock Correction Using Ambient Seismic Noise. Seismica 2024, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, B.M.; Yang, T.; Chen, Y.J.; Yao, H. Correction of OBS Clock Errors Using Scholte Waves Retrieved from Cross-Correlating Hydrophone Recordings. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 212, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, M.K.; Lin, F.-C.; Townend, J. Ambient Noise Cross-Correlation Observations of Fundamental and Higher-Mode Rayleigh Wave Propagation Governed by Basement Resonance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3556–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschi, L.; Weemstra, C. Stationary-Phase Integrals in the Cross Correlation of Ambient Noise. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 411–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, M.; Mordret, A.; Boué, P.; Brenguier, F.; Lecocq, T.; Courbis, R.; Hollis, D.; Campman, X.; Romijn, R.; Van der Veen, W. Ambient Noise Multimode Rayleigh and Love Wave Tomography to Determine the Shear Velocity Structure above the Groningen Gas Field. Geophys. J. Int. 2019, 218, 1781–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainan, C. Analysis and Prediction of the Evolution of Water Depth Topography in the Chengdao Sea Area of the Yellow River Delta; First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources: Qingdao, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, P.; Sabra, K.G.; Gerstoft, P.; Kuperman, W.A.; Fehler, M.C. P-Waves from Cross-Correlation of Seismic Noise. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L19303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonegawa, T.; Fukao, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Obana, K.; Kodaira, S.; Kaneda, Y. Ambient Seafloor Noise Excited by Earthquakes in the Nankai Subduction Zone. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Clayton, R.W.; Li, D. Higher-Mode Ambient-Noise Rayleigh Waves in Sedimentary Basins. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 206, 1634–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Thurber, C.H. Using Multicomponent Ambient Seismic Noise Cross-Correlations to Identify Higher-Mode Rayleigh Waves and Improve Dispersion Measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 222, 1590–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.C.; Yuan, H.M.; Liu, X.B.; Zhang, H. Dispersion of Scholte Wave under Horizontally Layered Viscoelastic Seabed. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 235, 1712–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, J.G. The Range of Existence of Rayleigh and Stoneley Waves. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Geophys. Suppl. 1947, 5, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Ajo-Franklin, J.B.; Lindsey, N.J.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, X. Space–Time Monitoring of Seafloor Velocity Changes Using Ambient Noise. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2023JB027953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viens, L.; Perton, M.; Spica, Z.J.; Nishida, K.; Yamada, T.; Shinohara, M. Understanding Surface Wave Modal Content for High-Resolution Imaging of Submarine Sediments with Distributed Acoustic Sensing. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 232, 1668–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seivane, H.; Schimmel, M.; Martí, D.; Sánchez-Pastor, P. Rayleigh Wave Ellipticity from Ambient Noise: A Practical Method for Monitoring Seismic Velocity Variations in the near-Surface. Eng. Geol. 2024, 343, 107768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonegawa, T.; Kimura, T.; Araki, E. Near-Field Body-Wave Extraction from Ambient Seafloor Noise in the Nankai Subduction Zone. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 8, 610993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Number of Effective Observations | Median Expected Delay (ms) | Median Error Before Correction (ms) | Median Error After Correction (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 116 | 50.103981 | 3.896019 | 2.103981 |

| Z | 116 | 50.103981 | 11.896019 | 9.896019 |

| X | 116 | 50.103981 | 7.103981 | 5.103981 |

| Y | 116 | 50.103981 | 4.896019 | 3.896019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, D.; Chen, B.; Cheng, L.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. A Multicomponent OBN Time-Shift Joint Correction Method Based on P-Wave Empirical Green’s Functions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010060

Jiang D, Chen B, Cheng L, Chen C, Li Y, Wang Y. A Multicomponent OBN Time-Shift Joint Correction Method Based on P-Wave Empirical Green’s Functions. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Dongxiao, Bingyu Chen, Lei Cheng, Chang Chen, Yingda Li, and Yun Wang. 2026. "A Multicomponent OBN Time-Shift Joint Correction Method Based on P-Wave Empirical Green’s Functions" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010060

APA StyleJiang, D., Chen, B., Cheng, L., Chen, C., Li, Y., & Wang, Y. (2026). A Multicomponent OBN Time-Shift Joint Correction Method Based on P-Wave Empirical Green’s Functions. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010060