Characteristics of Coastal Trapped Waves Generated by Typhoon ‘Soudelor’ in the Northwestern South China Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

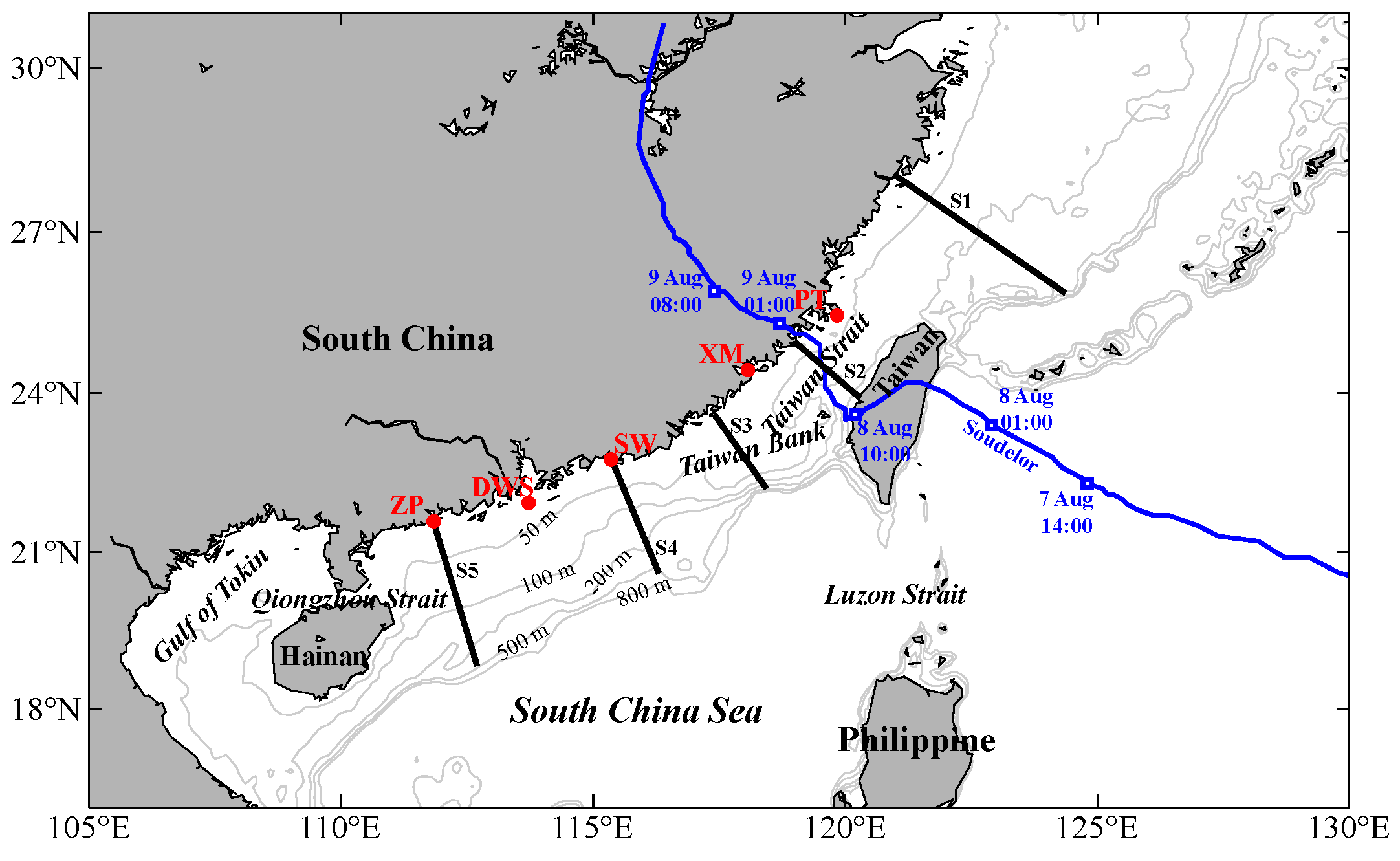

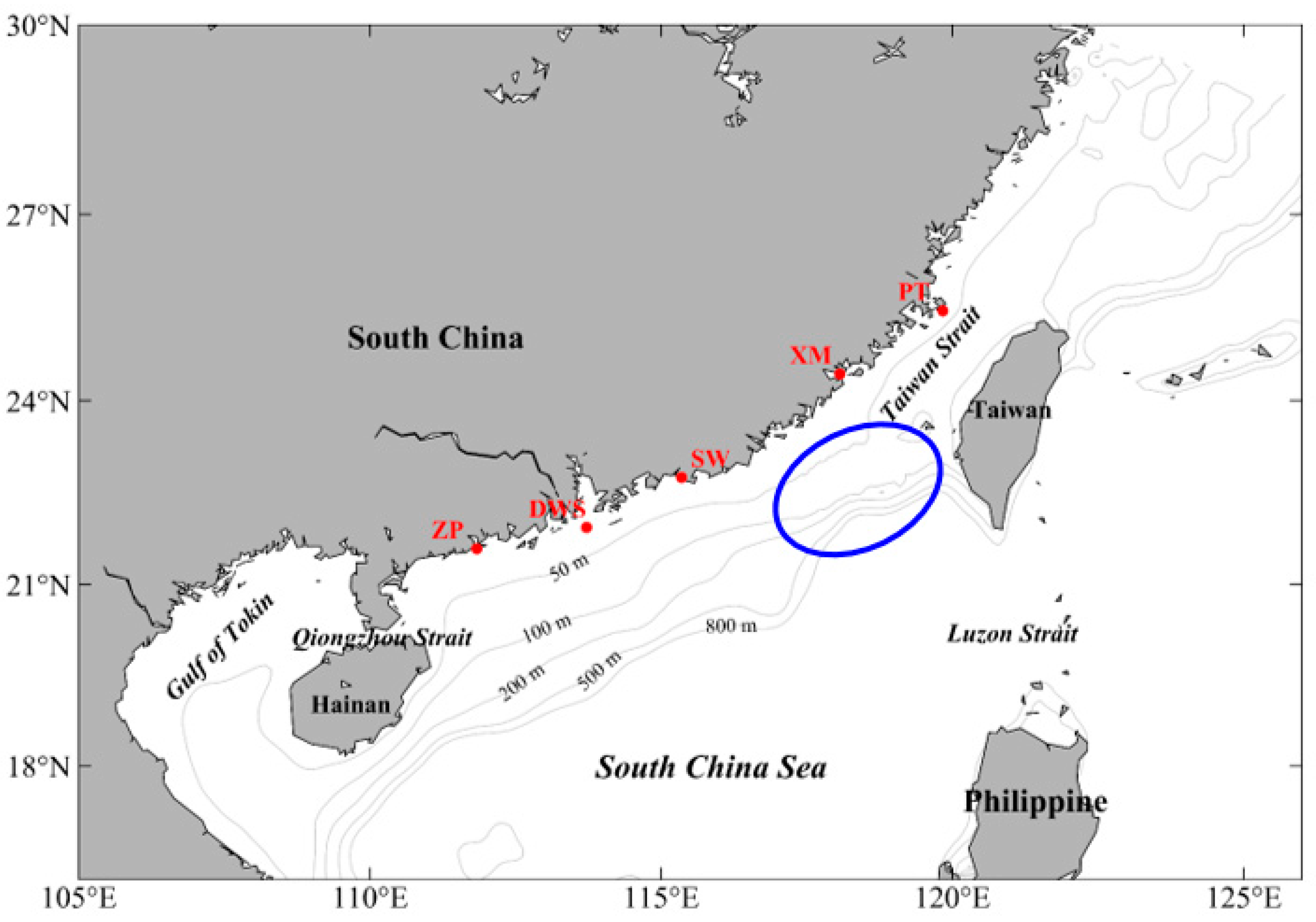

2.1. Observations

2.2. Sea Level, Current and Wind DATA Processing

2.3. Model Configuration

3. Results

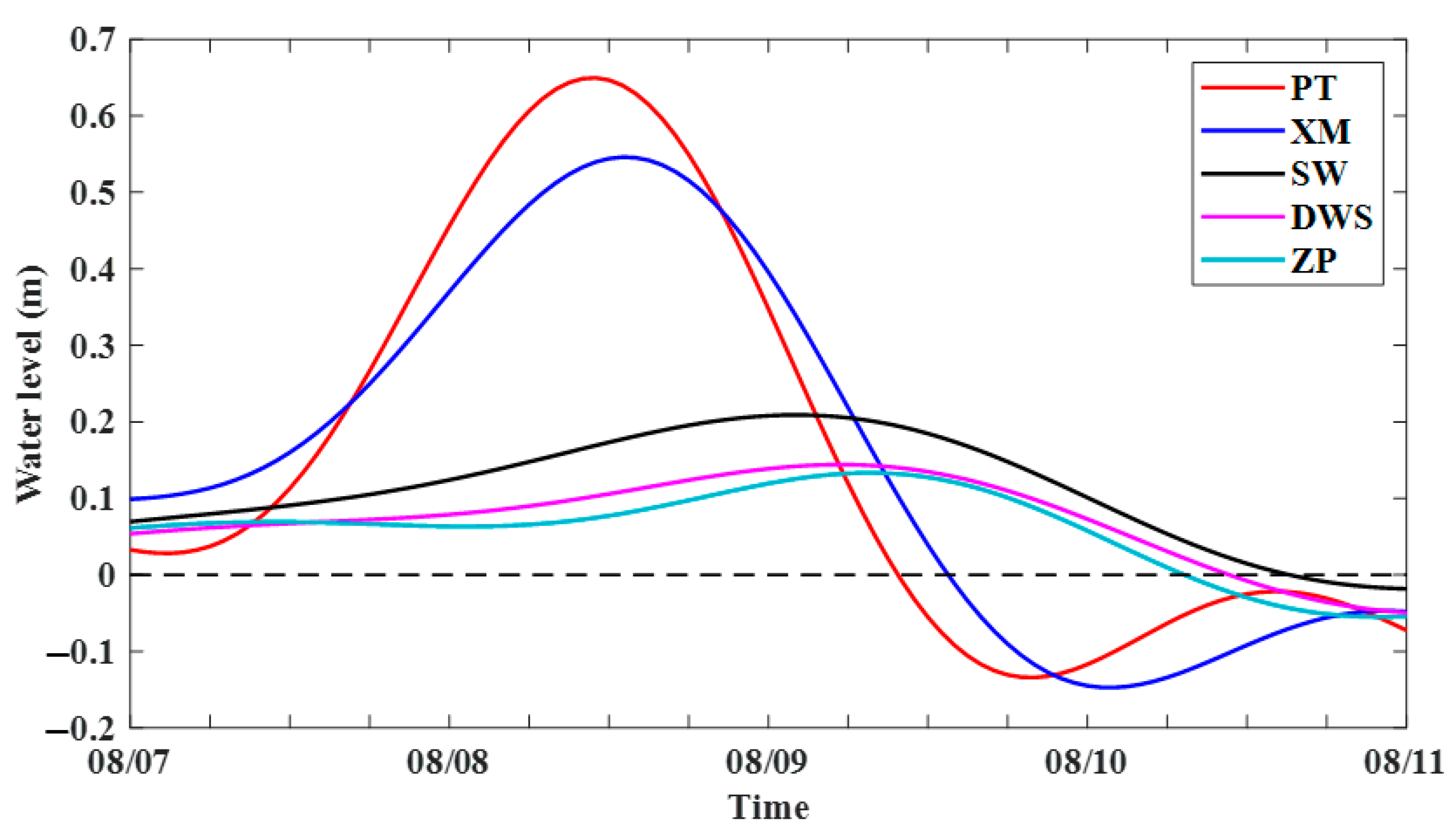

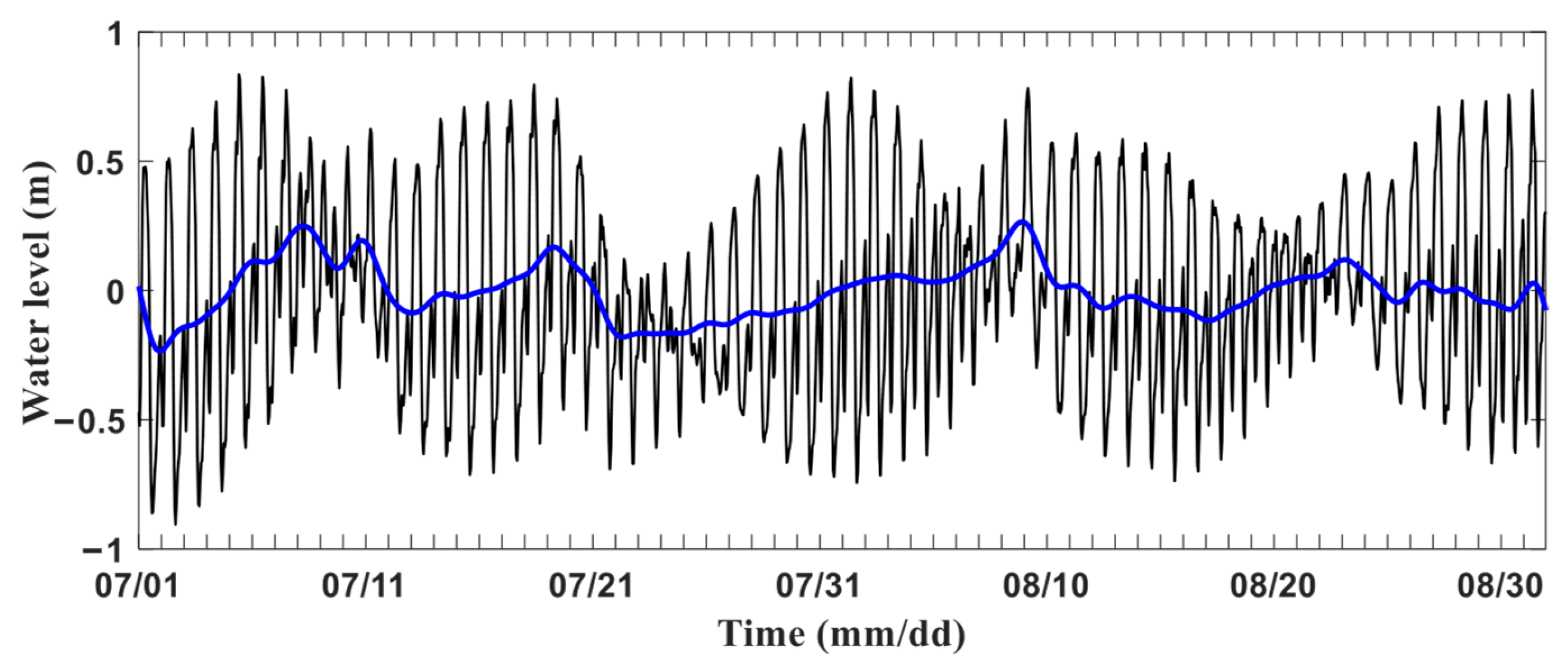

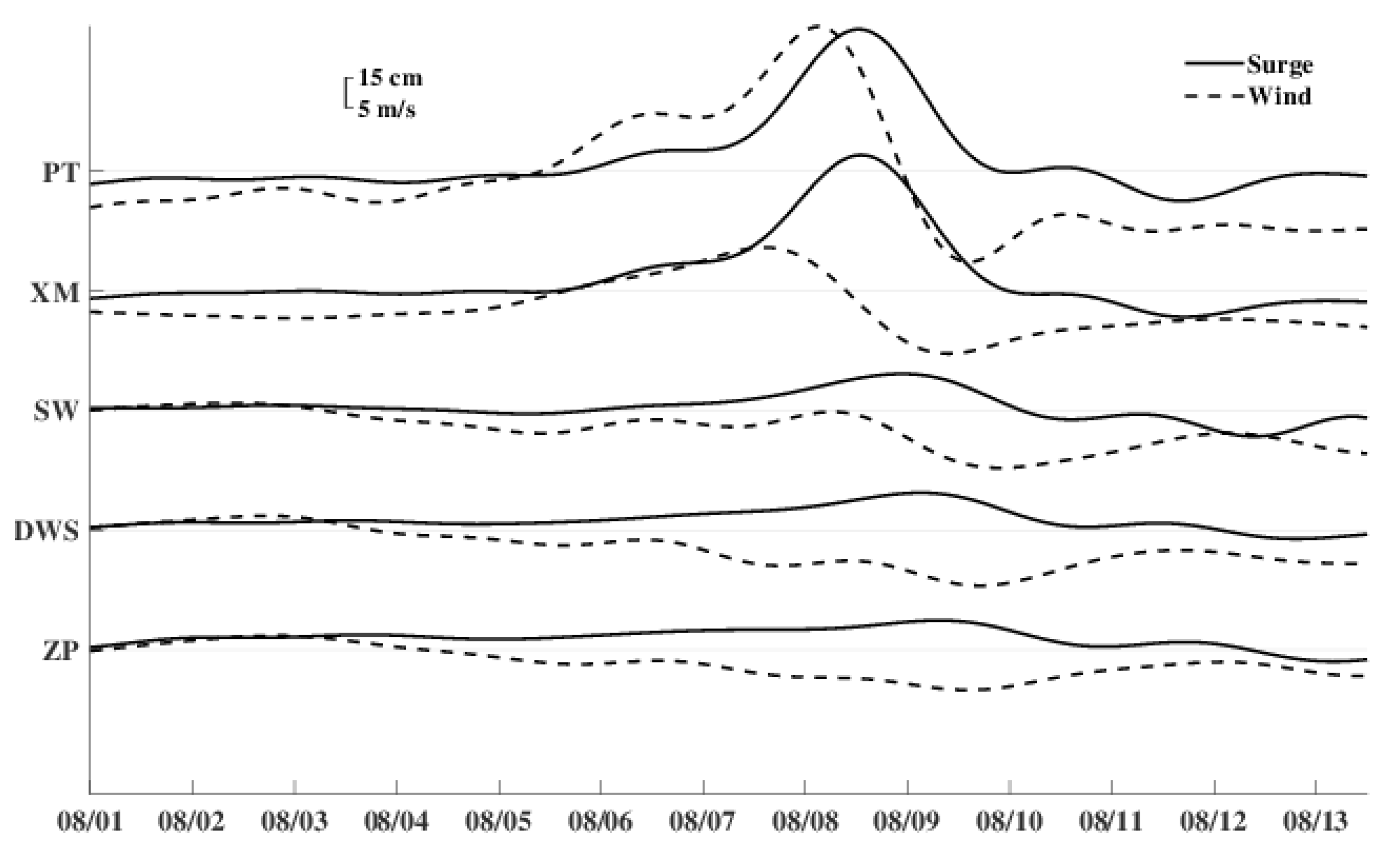

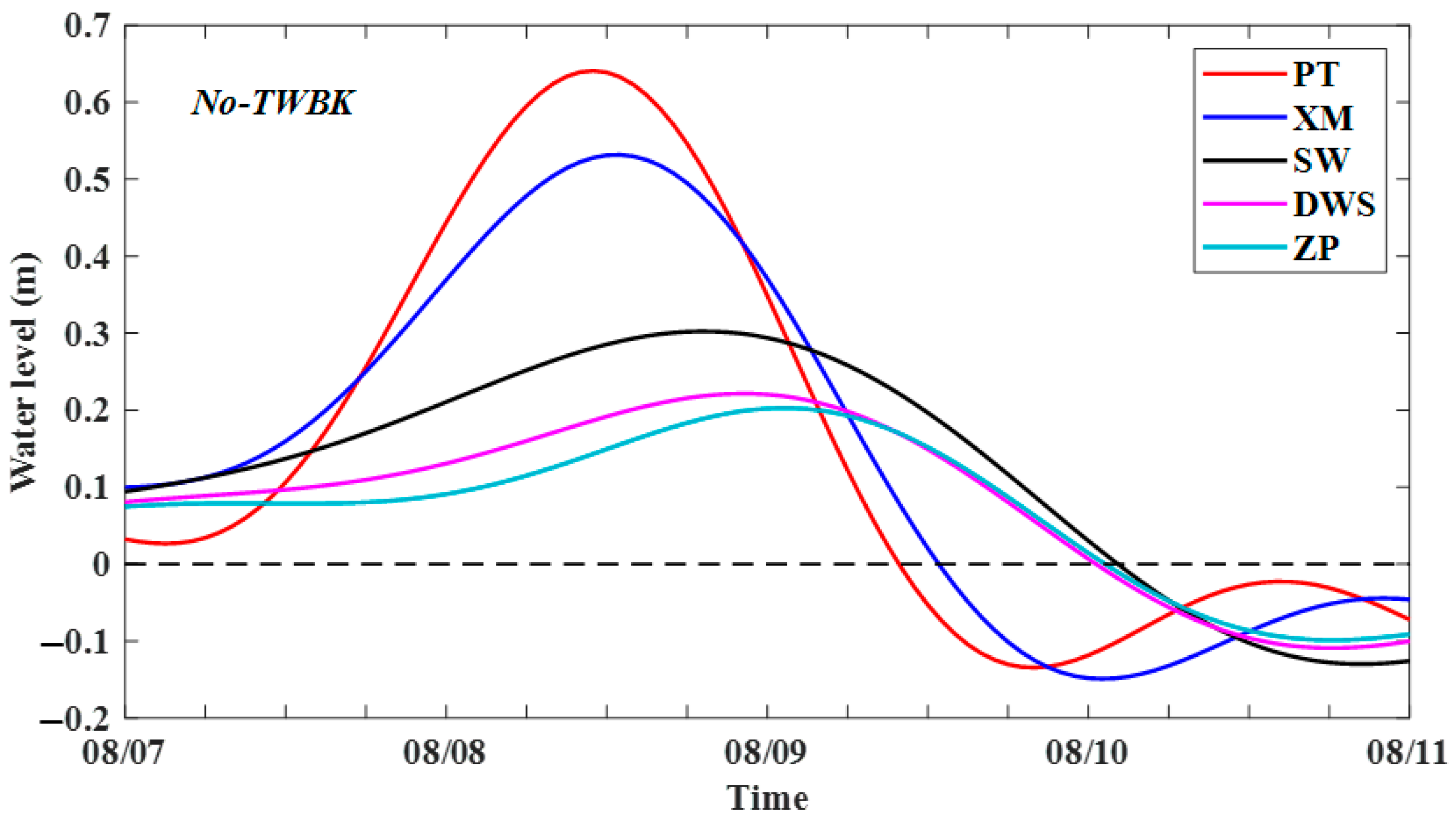

3.1. Correlation Analysis Between Sea Level and Wind

3.2. Phase Propagation Velocity of the CTW

| Stations | Distance (km) | Lags (h) | Vel (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT-XM | 210 | 2 | 29.2 |

| XM-SW | 335 | 13 | 7.2 |

| SW-DWS | 191 | 3 | 17.7 |

| DWS-ZP | 198 | 3 | 18.3 |

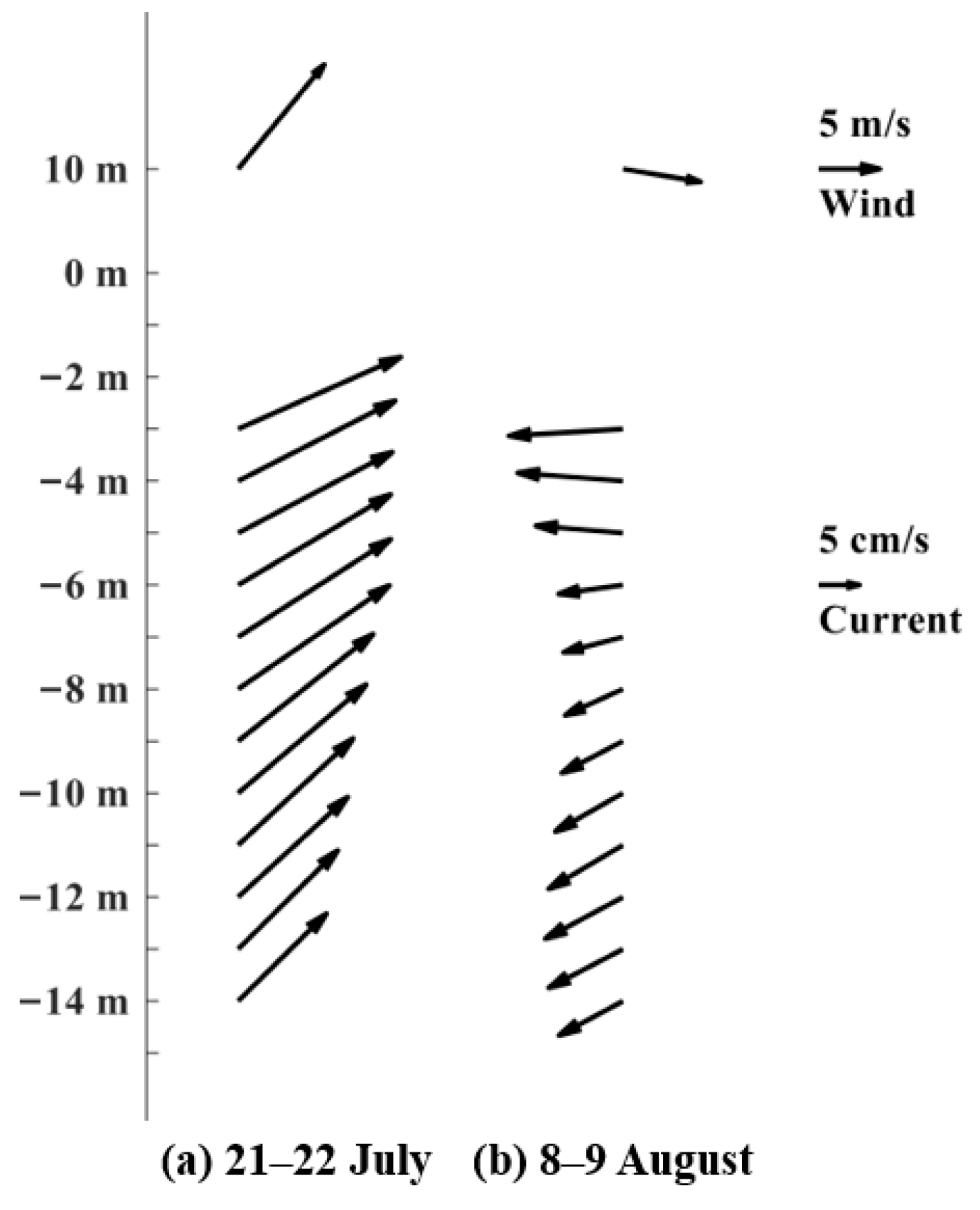

3.3. Current Characteristics at SW Station

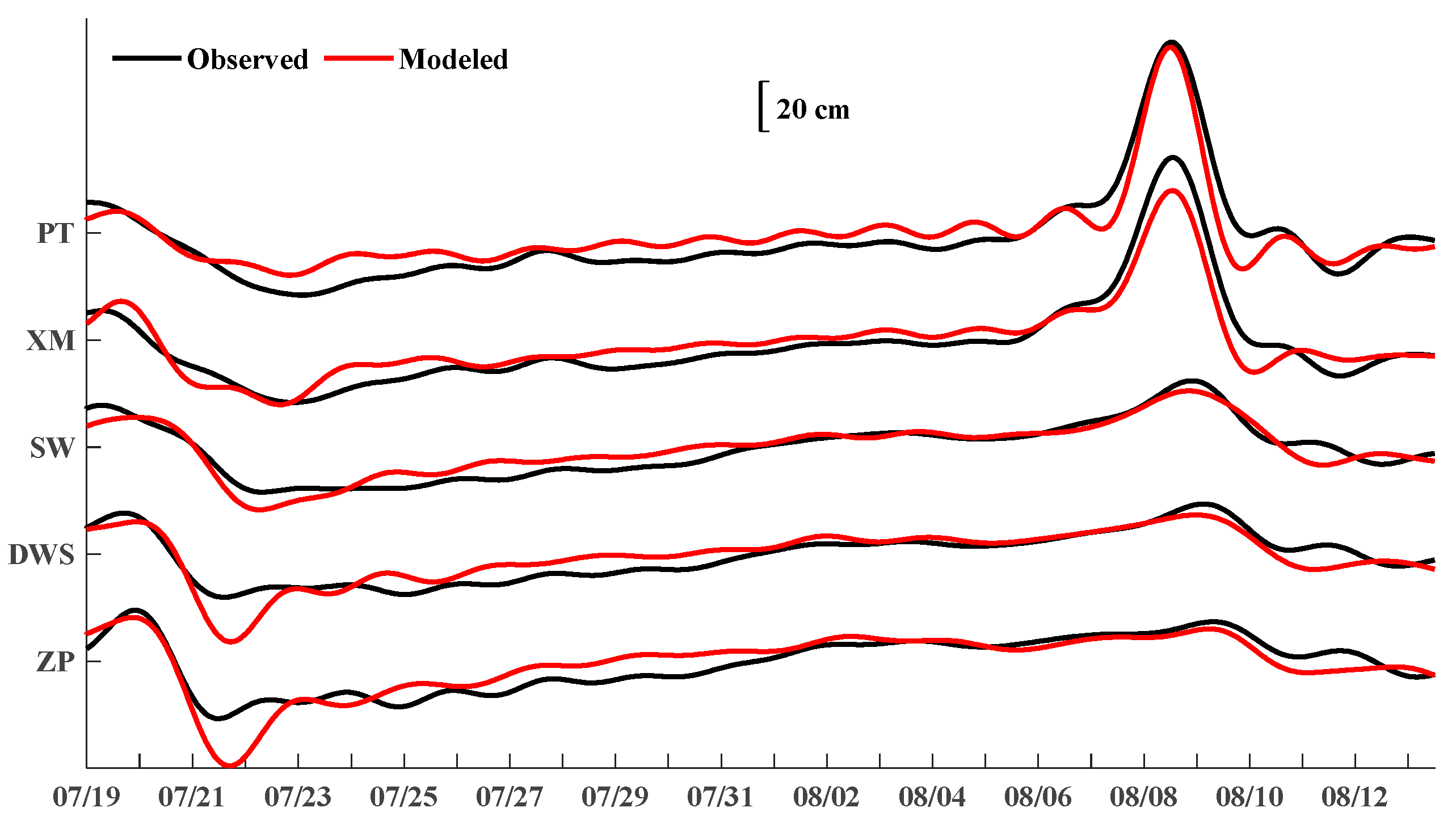

3.4. Model Validation

4. Discussions

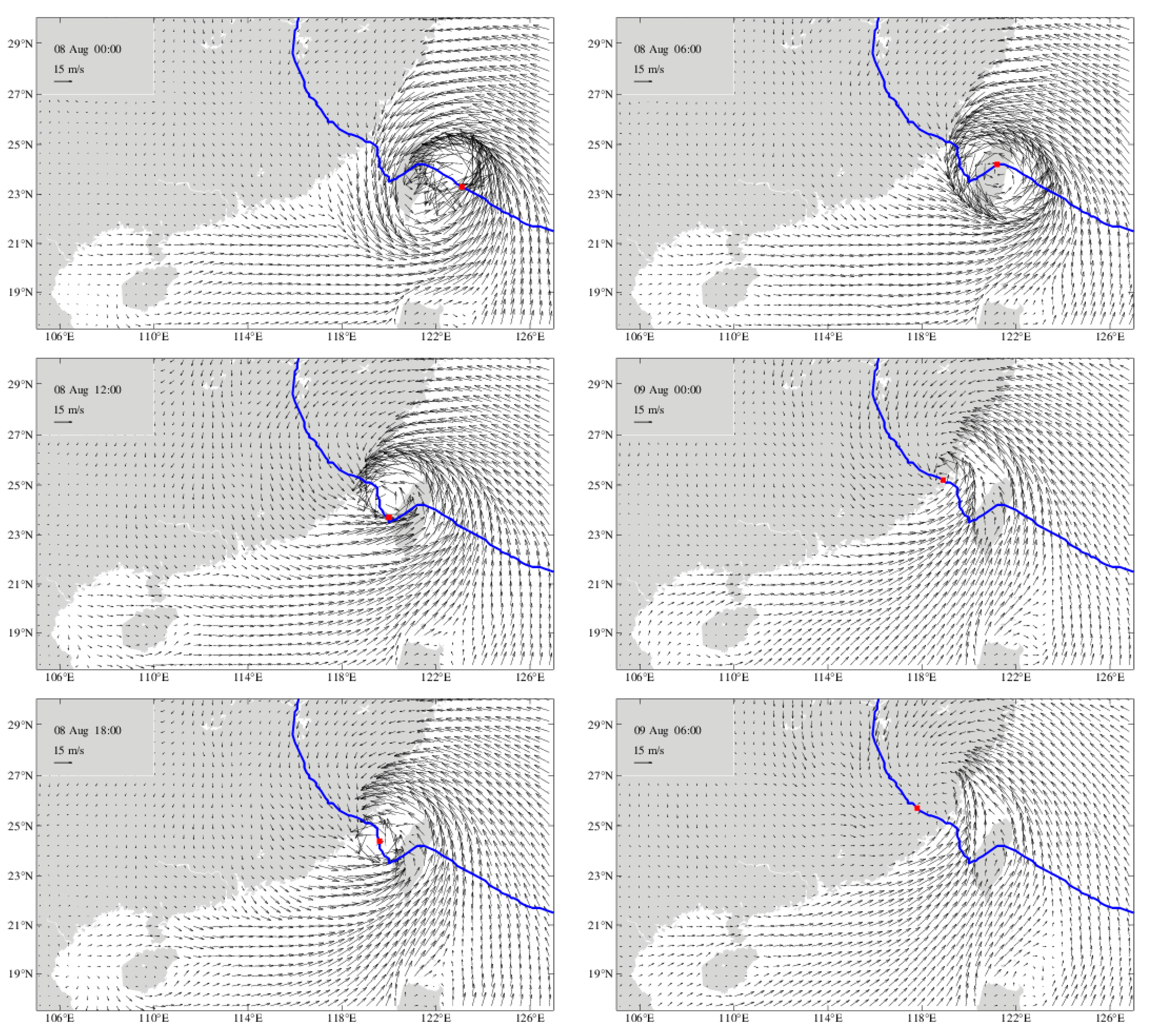

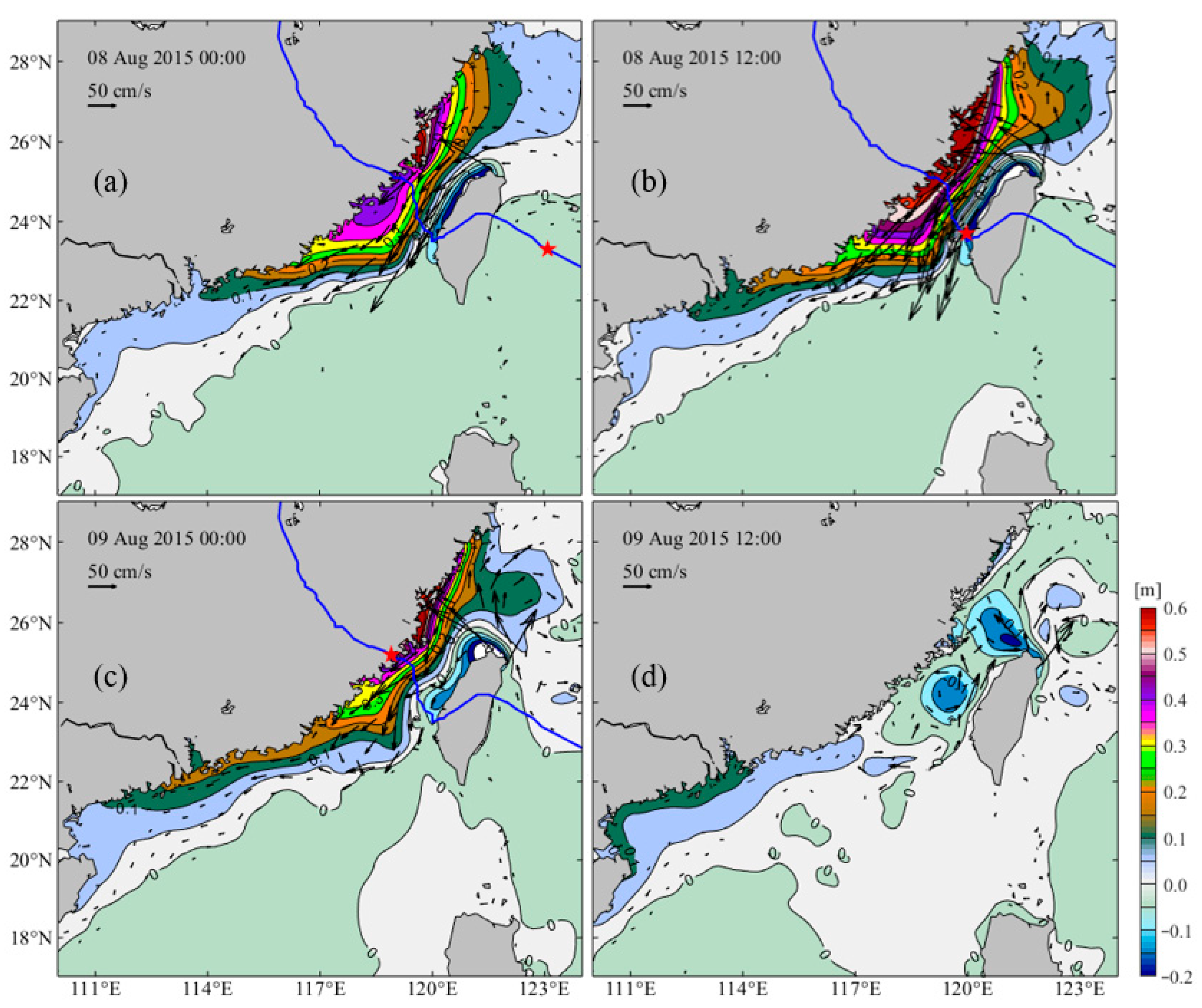

4.1. Propagation Process of the CTW Generated by Soudelor

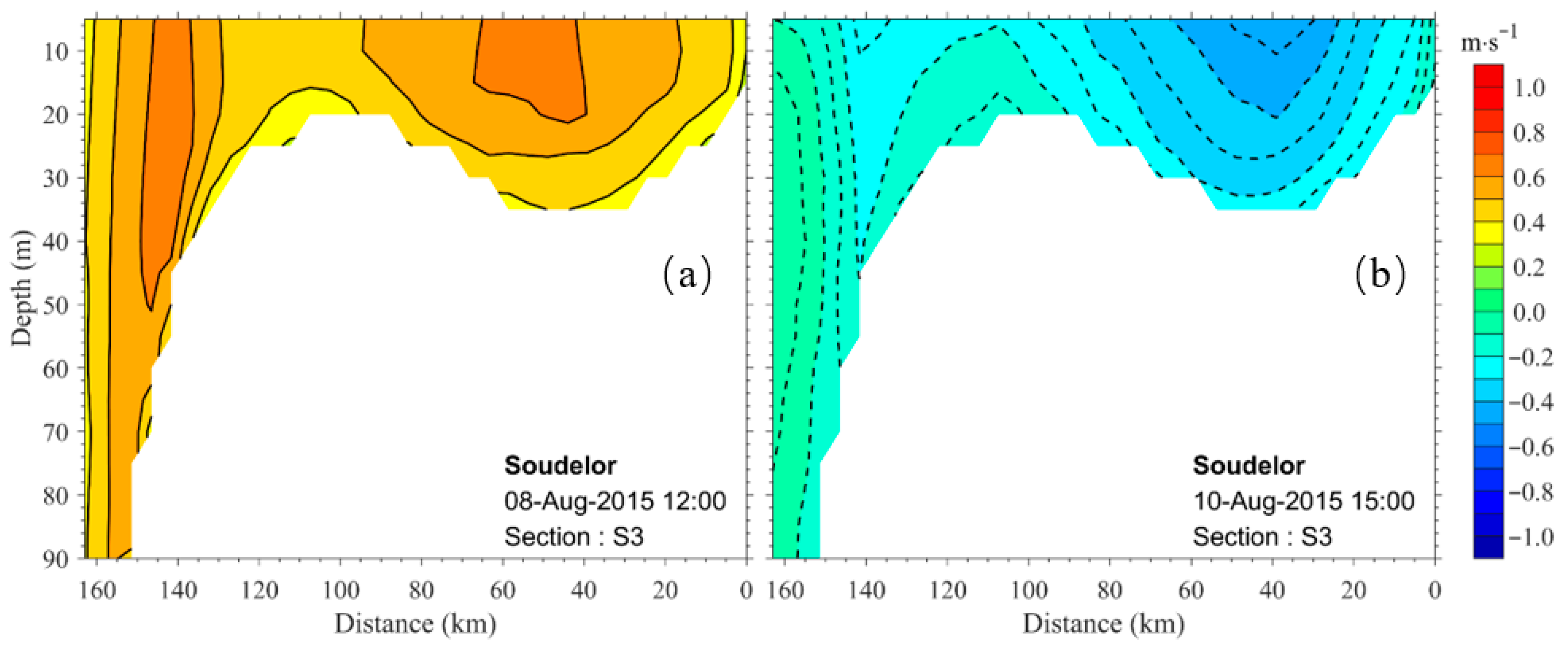

4.2. Spatiotemporal Variations of Current Structure at S3

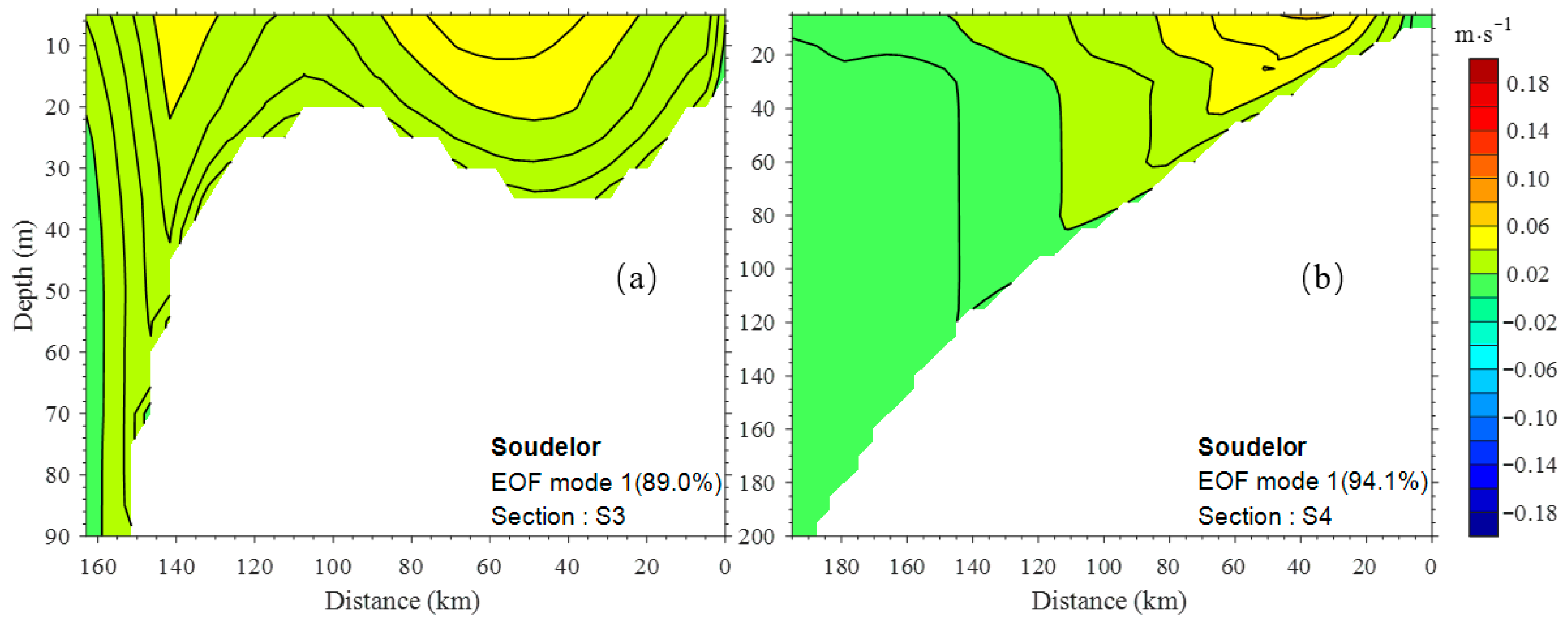

4.3. EOF Analysis of the S3 and S4

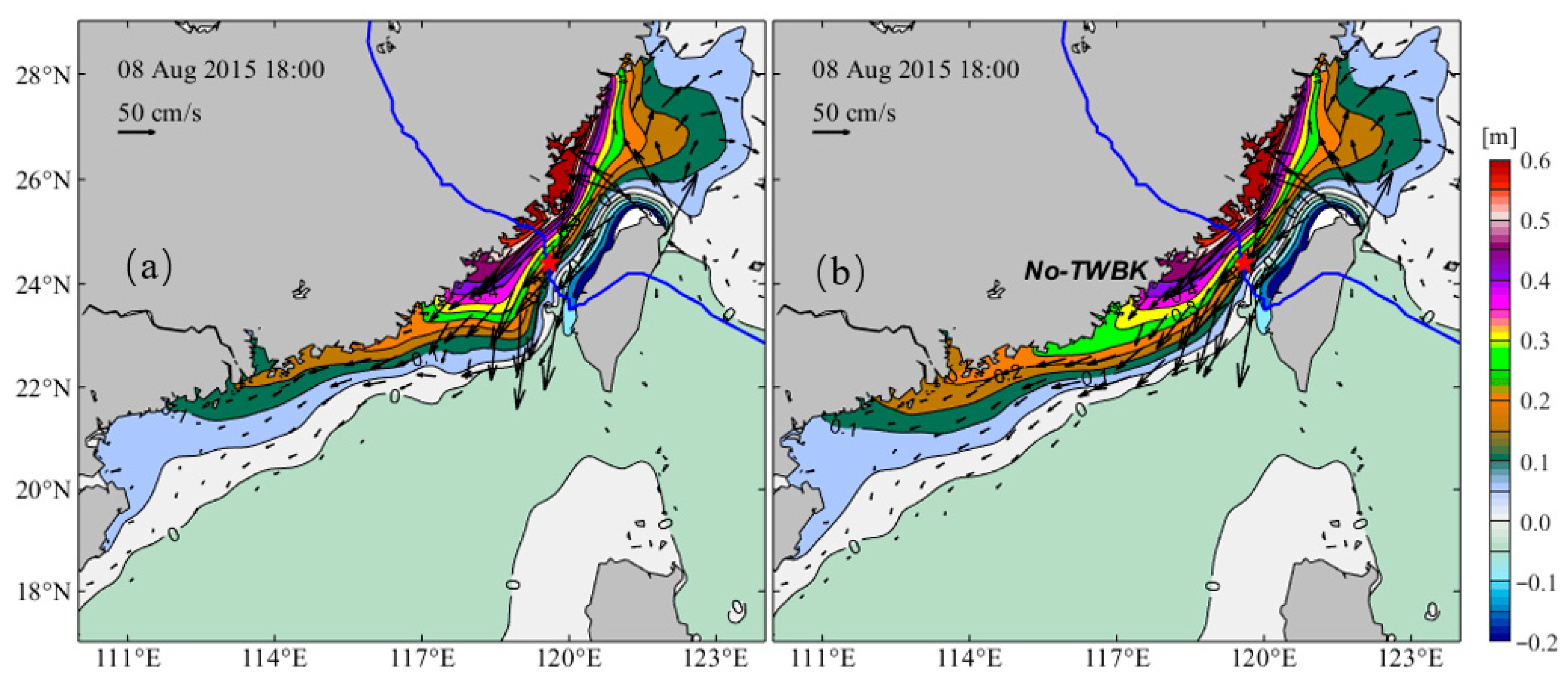

4.4. Impacts of the TWBK on the Phase Velocity of CTW

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mysak, L.A. Recent advances in shelf wave dynamics. Rev. Geophys. Space Phys. 1980, 18, 211–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankovsky, A.E. Large-scale edge waves generated by hurricane landfall. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2009, 114, C03014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huthnance, J.M. On trapped waves over a continental shelf. J. Fluid Mech. 1975, 69, 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huthnance, J.M. On coastal trapped waves: Analysis and numerical calculation by inverse iteration. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1978, 8, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.M.; Ogbuka, S. Coastal trapped waves: Normal modes, evolution equations, and topographic generation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2022, 52, 1835–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, R.; Pollmann, F.; Kelly, S.; Nikurashin, M. The lifecycle of topographically-generated internal waves. In Ocean Mixing: Drivers, Mechanisms and Impacts; Garabato, A.N., Meredith, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Hamon, B.V. The spectrums of mean sea level at Sydney, Coff’s Harbour, and Lord Howe Island. J. Geophys. Res. 1962, 67, 5147–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.N. A numerical study of sea level and current responses to Hurricane Frederic using a coastal ocean model for the Gulf of Mexico. J. Oceanogr. 1994, 50, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliot, M.; Pattiaratchi, C. Remote forcing of water levels by tropical cyclones in southwest Australia. Cont. Shelf Res. 2010, 30, 1549–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.P.; Qiao, F.L.; Zheng, Q.A. Coastal-trapped waves in the East China Sea observed by a mooring array in winter 2006. J. Oceanogr. 2013, 44, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.Y.; Pan, J.Y.; Guo, X.Y.; Zheng, Q.A. Introduction to the special section on regional environmental oceanography in the South China Sea and its adjacent areas (REO-SCS). J. Oceanogr. 2011, 67, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.Y.; Lau, T.K.; Chan, Y.W.; Cheung, P.; Lam, C.C.; Choy, C.W.; Chan, P.W. An observational analysis of Super Typhoon Yagi (2024) over the South China Sea. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2025, 137, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Dai, Y.F.; Chan, P.W.; Cheung, P.; Tang, J. Dual-aircraft joint observation of cloud microphysics of Typhoon Trami (2024) over the South China Sea. J. Meteorol. Res. 2025, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, D.S.; Chao, S.Y.; Wu, C.C.; Lin, I.I. Impacts of Typhoon Megi (2010) on the South China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. 2014, 119, 4474–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.C.; Tseng, R.S.; Centurioni, L.R. Typhoon-induced strong surface flows in the Taiwan Strait and Pacific. J. Oceanogr. 2010, 66, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Bao, X.W.; Shi, M.C. Characteristics of coastal trapped waves along the northern coast of the South China Sea during year 1990. Ocean Dyn. 2012, 62, 1259–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Zheng, Q.A.; Hu, J.Y.; Fan, Z.H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, T.; Zhu, B.L.; Xu, Y. Wavelet analysis of coastal trapped waves along the China coast generated by winter storms in 2008. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2015, 34, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.F.; Shi, H.Y.; Shi, M.C.; Guo, P.F.; Wu, L.Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, L. Model-simulated coastal trapped waves stimulated by typhoon in northwestern South China Sea. J. Ocean. Univ. China 2017, 16, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; He, T.; Zheng, Q.A.; Xu, Y.; Xie, L.L. Statistical analysis of dynamic behavior of continental shelf wave motions in the northern South China Sea. Ocean Sci. 2023, 19, 1545–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, Y.N.; Yu, X.L.; Gong, W.P. Seasonal variations of coastal trapped waves (CTWs)’ propagation in the south China sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 302, 108780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, E.H.; Brink, K.H. Coastal-trapped waves off the coast of South Africa: Generation, propagation and current structures. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1990, 20, 1206–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnay, E.; Kanamitsu, M.; Kistler, R.; Collins, W.; Deaven, D.; Gandin, L.; Iredell, M.; Saha, S.; White, G.; Woollen, J.; et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 1996, 77, 437–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Moorthi, S.; Wu, X.R.; Wang, J.D.; Nadiga, S.; Tripp, P.; Behringer, D.; Hou, Y.T.; Chuang, H.Y.; Iredell, M.; et al. The NCEP Climate Forecast System Version 2. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 2185–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowicz, R.; Beardsley, R.; Lentz, S. Classical tidal harmonic analysis including error estimates in MATLAB using T_TIDE. Comput. Geosci. 2002, 28, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, W.J.; Thomson, R.E. Data Analysis Methods in Physical Oceanography; Second and Revised Version; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Liu, H.; Beardsley, R.C. An unstructured, finite-volume, three-dimensional, primitive equation ocean model: Application to coastal ocean and estuaries. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2003, 20, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, G.L.; Yamada, T. Development of a turbulence closure model for geophysical fluid problem. Rev. Geophys. 1982, 20, 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations: I. The basic experiment. Mon. Weather Rev. 1963, 91, 99–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Shen, Y.M.; Guo, Y.K. Seasonal circulation and influence factors of the Bohai Sea: A numerical study based on Lagrangian particle tracking method. Ocean Dyn. 2010, 60, 1581–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Shen, Y.M. Development of an integrated model system to simulate transport and fate of oil spills in seas. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2010, 53, 2423–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesiello, P.; McWilliams, J.C.; Shchepetkin, A. Open boundary conditions for long-term integration of regional oceanic models. Ocean Model. 2001, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, K.H. Coastal-trapped waves and wind-driven currents over the continental shelf. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1991, 23, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, J.L.; Chapman, D.C. Scattering of continental shelf waves at a discontinuity in shelf width. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1987, 17, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, D.S.; Breaker, L.C.; Gemmill, W.H. A Proposed Definition for Vector Correlation in Geophysics: Theory and Application. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1993, 10, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denbo, D.W.; Allen, J.S. Rotary empirical orthogonal function analysis of currents near the Oregon coast. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1984, 14, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, A.H.; Fyfe, J.C.; Ambaum, M.H.P.; Stephenson, D.B.; North, G.R. Empirical orthogonal functions: The medium is the message. J. Clim. 2009, 22, 6501–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo-Urbina, J.M.; Arts, G.; Gräwe, U.; Clercx, H.J.H.; Gerkema, T.; Duran-Matute, M. Atmospherically driven seasonal and interannual variability in the Lagrangian transport time scales of a multiple-inlet coastal system. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2023, 128, e2022JC019522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.S. Continental shelf waves and alongshore variations in bottom topography and coastline. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1976, 6, 864–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, J.F. Coastal-trapped wave scattering into and out of straits and bays. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1991, 21, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, M.A. A comparison of long coastal-trapped wave theory with remote storm generated wave events in the Gulf of California. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1992, 22, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, O.; Shaffer, G. Wind-driven, coastal-trapped waves off the Island of Gotland, Baltic Sea. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1998, 28, 2117–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station | 2 to 12 August 2015 | |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation | Lags (h) | |

| PT | 0.89 | 13 |

| XM | 0.85 | 19 |

| SW | −0.85 | −38 |

| DWS | −0.84 | −21 |

| ZP | −0.68 | −26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, X.; Wu, L.; Xing, C.; Shi, M.; Guo, P. Characteristics of Coastal Trapped Waves Generated by Typhoon ‘Soudelor’ in the Northwestern South China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010004

Cao X, Wu L, Xing C, Shi M, Guo P. Characteristics of Coastal Trapped Waves Generated by Typhoon ‘Soudelor’ in the Northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Xuefeng, Lunyu Wu, Chuanxi Xing, Maochong Shi, and Peifang Guo. 2026. "Characteristics of Coastal Trapped Waves Generated by Typhoon ‘Soudelor’ in the Northwestern South China Sea" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010004

APA StyleCao, X., Wu, L., Xing, C., Shi, M., & Guo, P. (2026). Characteristics of Coastal Trapped Waves Generated by Typhoon ‘Soudelor’ in the Northwestern South China Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010004