Investigating the Genesis and Migration Mechanisms of Subsea Shallow Gas Using Carbon Isotopic and Lithological Constraints: A Case Study from Hangzhou Bay, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

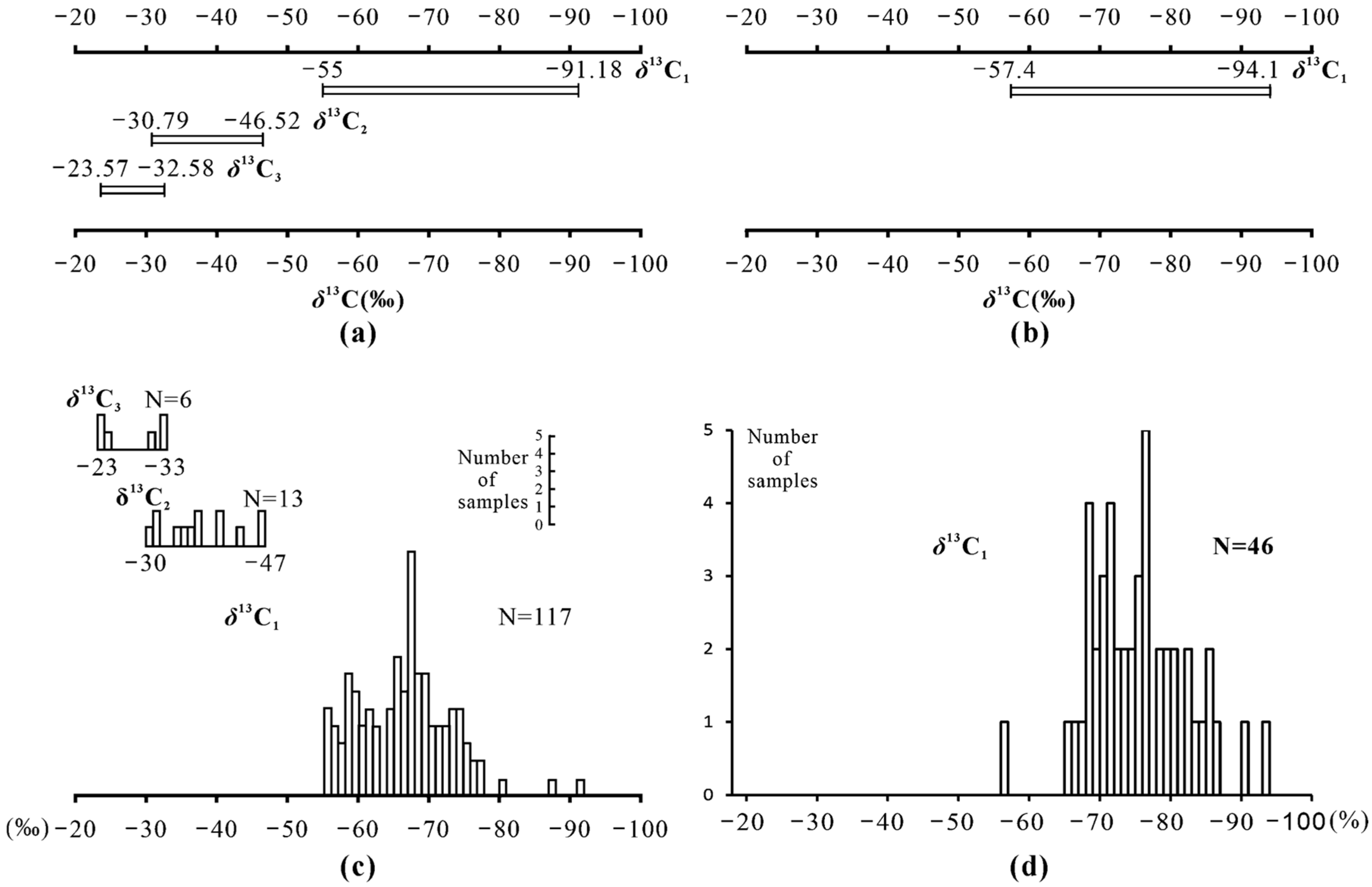

4.1. Isotopic and Chemical Composition of Shallow Gas

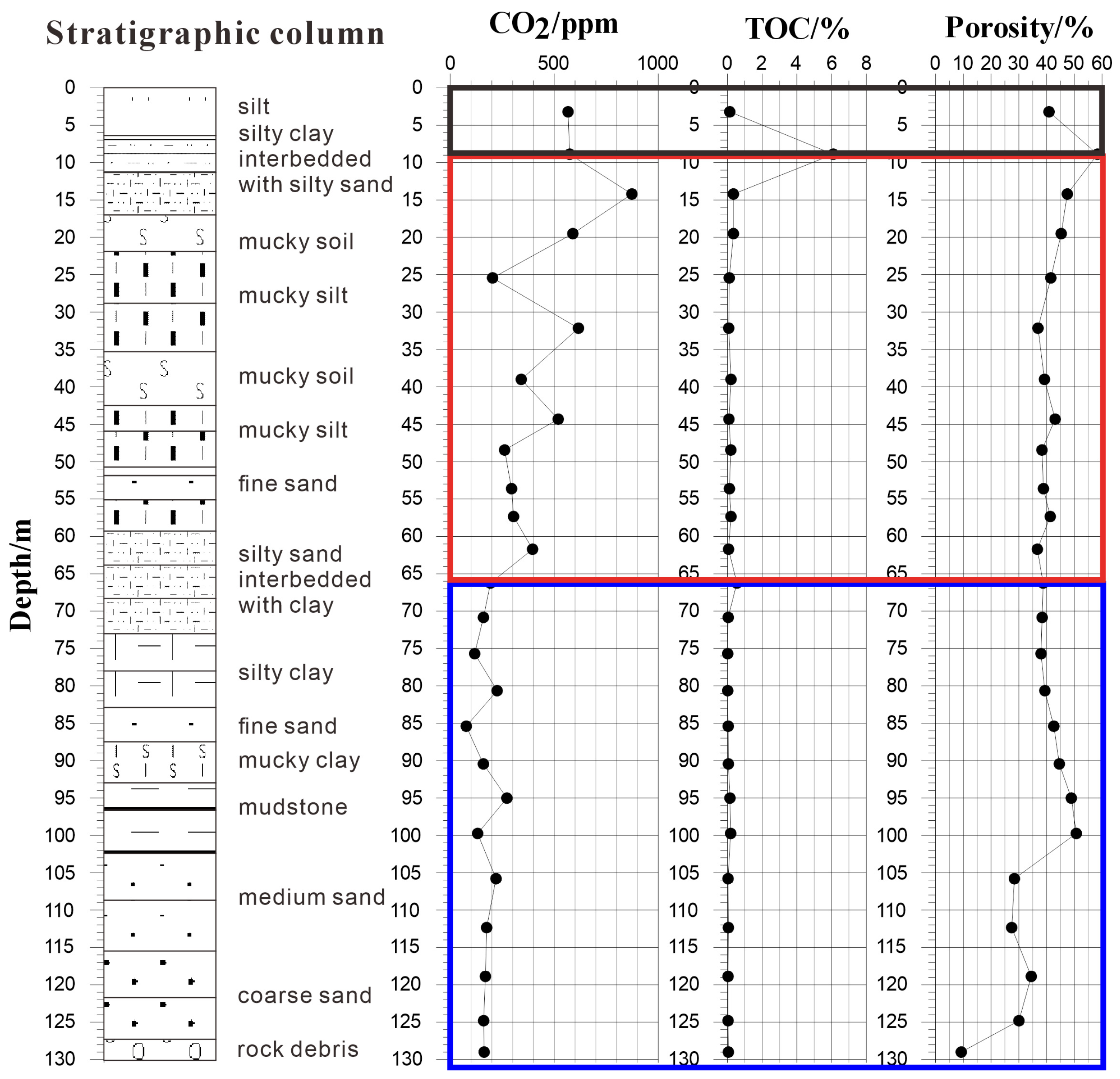

4.2. Vertical Distribution of Methane and Isotopes

4.3. Regression Analysis of Isotopes and Concentration

5. Discussion

5.1. Identification of Biogenic Gas Origin

5.2. Interpretation of Vertical Zonation and Migration Mechanisms

5.2.1. Disturbed Zone (0–6.40 m): Near-Surface Gas Dissipation

5.2.2. Active Zone (6.40–64.00 m): Mixing-Homogenization and Fractionation Windows

5.2.3. Residual Zone (64.00–96.85 m): Adsorptive Fractionation and Reservoir Depletion

5.3. Rethinking the Classical Rayleigh Fractionation Model and Methodological Innovation

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study confirms that the shallow gas in the study area is typical primary biogenic gas generated via CO2 reduction, consistent with the saline depositional environment of the marine–continental transition facies in Hangzhou Bay. Its vertical distribution exhibits a clear tripartite zonation controlled by lithology: a Disturbed Zone (0–6.40 m), an Active Zone (6.40–64.00 m), and a Residual Zone (64.00–96.85 m). The gas occurrence and fractionation mechanisms differ significantly among these zones: the Disturbed Zone is dominated by high-permeability silt where the absence of a seal leads to gas escape; the Active Zone is characterized by clayey soils that cause multi-source mixing and homogenization (δ13C-CH4 ≈ −75.6‰), with significant adsorptive fractionation in high-permeability sand layers increasing δ13C-CH4 to −57.4‰; and the Residual Zone follows adsorption–desorption-controlled Rayleigh fractionation (δ13C-CH4 decreasing from −75‰ to −94‰), indicating gas reservoir depletion. This demonstrates that lithology-controlled migration is a more fundamental governing factor than traditional Rayleigh fractionation in heterogeneous clay-rich sedimentary systems.

- (2)

- This study overcomes the limitations of the traditional Rayleigh fractionation model in heterogeneous systems by proposing a “zonal verification–mechanism tracing” analytical framework. A key innovation of this method is that, relying solely on δ13C-CH4 and CH4 concentration data, it accurately deciphers complex migration–fractionation mechanisms by identifying the mathematical artifact of high overall goodness-of-fit (R2 = 0.8049)—i.e., the statistical superposition of mixing-homogenization in the Active Zone and adsorption–desorption controlled Rayleigh fractionation in the Residual Zone. This provides a new lithology-constrained paradigm for interpreting gas migration in data-sparse engineering survey contexts, significantly reducing reliance on multi-parameter and high-density data.

- (3)

- In practical terms, this study provides direct support for shallow gas hazard assessment and resource exploration: ① The shallow Disturbed Zone poses a low engineering risk level due to persistent gas escape caused by the lack of an effective seal, preventing significant gas accumulation and making it non-threatening to submarine engineering construction; ② A diagnostic framework for identifying depleted biogenic gas reservoirs is established, based on the co-occurrence of low CH4 concentrations (<~1000 ppm) and a strong negative linear δ13C-CH4 gradient (R2 > 0.7) in the Residual Zone, optimizing the selection of exploration targets; ③ The proposed “zonal verification–mechanism tracing” framework can be extended to other low-data-density regions, enabling high-resolution mechanistic interpretation with limited data.

- (4)

- Future research should build on the lithology–isotope coupling analysis and tripartite zonation framework proposed in this study by integrating more diverse data—such as porewater geochemical indices, high-resolution seismic profiles, and microbial community data—to further validate and refine the universality and accuracy of this methodology. Its application can be expanded to preliminary submarine engineering investigations and risk assessments in other regions, offering a reliable reference for engineering decision-making under data-scarce conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VPDB | Vienna PeeDee Belemnite |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

References

- Ye, Y.C.; Chen, J.R.; Pan, G.F.; Liu, K. A Study of Formation Cause, Existing Characteristics of the Shallow Gas and Its Danger to Engineering. Donghai Mar. Sci. 2003, 21, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X.Y. Methane in Offshore Sediments. Earth 2023, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, P.; Orsi, T.; Richardson, M.; Anderson, A. Distribution of free gas in marine sediments: A global overview. Geo-Mar. Lett. 2001, 21, 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X.Y.; Yin, P.; Xie, Y.Q.; Cao, K.; Chou, J.D.; Li, M.N.; Li, X. Advancements in the Study of Shallow Gas in the Coastal Waters of China. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2024, 44, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.; Jiao, J.J.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, H.S.; Yin, Y.X. Distribution and Seismic Reflection Characteristics of Shallow Gas in Bohai Sea. Period. Ocean Univ. China (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 47, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, H.; Chiocci, F.L.; Berndt, C.; Çağatay, M.N.; Ferreira, T.; Fortes, C.J.E.M.; Gràcia, E.; González Vega, A.; Kopf, A.J.; Sørensen, M.B.; et al. Marine Geohazards: Safeguarding Society and the Blue Economy from a Hidden Threat; European Marine Board: Ostend, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, M.; Judd, A.G. Seabed Pockmarks and Seepages: Impact on Geology, Biology and the Marine Environment; Graham & Trotman: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen, T.; Murphy, S.; Loncke, L.; Henriet, J.-P. Very high-resolution seismic mapping of shallow gas in the Belgian coastal zone. Cont. Shelf Res. 2002, 22, 2291–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G.; Caccavale, M. New seismoacoustic data on shallow gas in Holocene marine shelf sediments, offshore from the Cilento Promontory (Southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, G. Seismo-stratigraphic data of the Gulf of Pozzuoli (Southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy): A review and their relationships with the new bradyseismic crisis. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.H.; Huang, Y.Q.; Zeng, H.X.; Kong, L.W. Engineering Geological Features and Shallow Gas Distribution in South Bank of Hangzhou Bay Bridge. Rock Soil Mech. 2002, 23 (Suppl. S1), 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.Q.; Wang, Y.; Lei, X.W.; Lai, X.H.; Chen, K.W. Engineering Geological Conditions and Shallow Gas Hazard Analysis of Jiayong Cross-sea High-speed Railway Bridge. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2022, 42, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.P.; Wang, Y.; Song, S.; Cheng, C.; Jia, P.F. Geological Occurrence Characteristics of Shallow Gas in Yangtze River Delta and Their Effect on Cross-river Tunnel. China Sci. 2024, 19, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, J.G.; Zhang, T.W.; Pang, Z.Y. Study on the Simulation of Shallow Gas Invasion and Blowout in Deep Water Drilling. Petrochem. Ind. Appl. 2023, 42, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, G. Submarine instability processes on the continental slope offshore of Campania (Southern Italy). GeoHazards 2025, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Yin, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Tyagi, M.; Sun, T.; Zhou, X. Field Data Analysis and Risk Assessment of Shallow Gas Hazards Based on Neural Networks During Industrial Deep-water Drilling. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 232, 109079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, A.; Knapp, J.H.; Sleeper, K.; Lutken, C.B.; Macelloni, L.; Knapp, C.C. Spatial Distribution of Gas Hydrates from High-resolution Seismic and Core Data, Woolsey Mound, Northern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2013, 44, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.J. Internal Structure Features and Simulation of Gas Migration Process of Gas-bearing Soil in the Chongming-Taicang River-Crossing Area. Master’s Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, M.; Svensen, H.; Forsberg, C.F.; Johansen, H.; Fichler, C.; Fosså, J.H.; Jonsson, R.; Rueslåtten, H. Complex pockmarks with carbonate-ridges off mid-Norway: Products of sediment degassing. Mar. Geol. 2005, 218, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, B.B.; Brooks, J.M.; Sackett, W.M. A Geochemical Model for Characterization of Hydrocarbon Gas Sources in Marine Sediments. In Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 2–5 May 1977; pp. 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Whiticar, M.J. Carbon and Hydrogen Isotope Systematics of Bacterial Formation and Oxidation of Methane. Chem. Geol. 1999, 161, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.X.; Chen, Y. Carbon Isotopic Characteristics and Identification Marks of Alkane Components in Biogas of China. Sci. China (Ser. B Chem. Life Sci. Earth Sci.) 1993, 23, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Fan, D.; Su, J.; Guo, X. Controls on shallow gas distribution, migration, and associated geohazards in the Yangtze subaqueous delta and the Hangzhou Bay. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Guo, X.J.; Wu, J.X. Progress in analysis and monitoring technology for gas migration in submarine sediments. Prog. Geophys. 2022, 37, 869–881. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.J.; Romanak, D.K.; Meckel, A.T. Assessment of shallow subsea hydrocarbons as a proxy for leakage at offshore geologic CO2 storage sites. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2018, 74, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z.M.; Jin, B.F.; Wang, X.D.; Lin, Y.S. The Development and Management of Quaternary Extra shallow Gas Reservoirs in Hangzhou Bay. Nat. Gas Ind. 1997, 17, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.X.; Yang, X.F.; Liu, Y.Y.; Lu, S.F.; Liu, W.P.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.B.; Zhang, X.T.; Zhang, W.T.; et al. Characteristics and geological implications of carbon isotope fractionation during deep shale gas production: A case study of the Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Silurian Longmaxi Formation in the Luzhou Block of Southern Sichuan Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2024, 44, 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.J. Study on Non-Linear Diffusion Mechanism and Flow Characteristics of Methane Isotope Gas in Porous Media. Master’s Thesis, Soochow University, Soochow, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.F.; Meng, K.; Huang, Y.G.; Wang, H.; Zheng, X.P.; Hu, W.W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.X.; He, M.Q.; Wang, B. Characteristics and geological significance of methane carbon isotope of released gas from Carboniferous Benxi coal rock in Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2025, 36, 1728–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Lord Rayleigh, O.M.F.R.S. On the Distillation of Binary Mixtures. Philos. Mag. 1902, 4, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C. Biogas Generation Conditions in Weihe Basin. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2021, 28, 614–619+630. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z.F.; Zhang, Z.X.; Liu, H.S. Contrast Between Traps at the Shallow Sub bottom Depth and the Seismic Reflection Features of Shallow Gas. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2009, 29, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, M.Y.; Liang, W.Y.; Wang, F.P. Methane Biotransformation in the Ocean and Its Effects on Climate Change. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2018, 48, 1568–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.A.; Sun, X.J.; Wang, J.P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L. Physical Simulating Experiment of Natural Gas Migration and Its Characteristics of Composition Differentiation and Carbon Isotope Fractionation. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2005, 27, 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.; Zhan, L.; Lu, H.; Hou, G. Structures in Shallow Marine Sediments Associated with Gas and Fluid Migration. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.F.; Tang, X.Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.Y. Distribution characteristics and fractionation mechanism of carbon isotope of coalbed methane. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2006, 49, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.B.; Lu, S.F.; Li, J.Q.; Zhang, P.F.; Wang, S.Y.; Feng, W.J.; Wei, Y.B. Carbon isotope fractionation during shale gas transport: Mechanism, characterization and significance. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2020, 50, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Num. | C1/ppm | C2/ppm | C3/ppm | C1/(C2 + C3) | δ13C1 (‰) | δ13C-CO2 (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1-2 | 6.1 | na | na | na | −72.9 | −17.5 |

| D1-5 | 5744.1 | na | na | na | −74.9 | −10.9 |

| D1-6 | 2914.2 | na | na | na | −68.7 | −20.6 |

| D2-2 | 3237.7 | 0.1 | 0.28 | 8520.26 | −79.6 | na |

| D2-3 | 2556.4 | 0.2 | na | 12,782.00 | −77.6 | −14.1 |

| D2-4 | 7425.7 | na | na | na | −66.6 | −11.0 |

| D2-5 | 1791.8 | na | na | na | −69.3 | −17.0 |

| D3-1 | 6205.1 | 0.8 | 7.86 | 716.52 | −85.3 | na |

| D3-2 | 3273.6 | na | na | na | −80.2 | na |

| D3-3 | 4133.2 | 0.1 | na | 41,332.00 | −83.0 | na |

| D3-7 | 2330.3 | na | na | na | −70.5 | −19.5 |

| D3-10 | 215.0 | na | na | na | −86.9 | −17.8 |

| D4-1 | 134.8 | 0.1 | na | 1348.00 | −87.7 | na |

| D4-2 | 175.5 | 0.4 | na | 438.75 | −83.5 | na |

| D4-5 | 6442.1 | na | na | na | −69.2 | na |

| D5-1 | 10.3 | na | na | na | na | −16.4 |

| D5-2 | 7589.2 | na | na | na | −77.1 | −14.9 |

| D5-3 | 6780.3 | na | na | na | −76.6 | −18.8 |

| D5-4 | 6314.1 | na | na | na | −77.1 | −11.7 |

| D5-6 | 16,940.0 | na | na | na | −76.2 | −6.1 |

| D5-7 | 5020.0 | 0.1 | 5.97 | 827.02 | −73.8 | na |

| D5-8 | 7267.2 | 0.1 | na | 72,672.00 | −75.1 | −15.8 |

| D5-9 | 3235.5 | 0.1 | na | 32,355.00 | −74.7 | na |

| D5-10 | 9655.7 | na | na | na | −57.4 | na |

| D5-11 | 4022.6 | na | na | na | −77.4 | na |

| D5-12 | 6205.7 | na | na | na | −76.2 | na |

| D5-13 | 975.3 | na | na | na | −80.2 | na |

| D5-14 | 935.4 | 0.1 | na | 9354.00 | −81.1 | na |

| D5-15 | 978.0 | 0.2 | na | 4890.00 | −79.6 | na |

| D5-16 | 1136.4 | 0.2 | na | 5682.00 | −84.4 | na |

| D5-17 | 801.6 | 0.5 | na | 1603.20 | −86.8 | na |

| D5-18 | 315.4 | na | na | na | −91.4 | na |

| D5-19 | 180.2 | 0.2 | na | 901.00 | −94.1 | na |

| D5-20 | 131.4 | na | na | na | na | na |

| D5-21 | 173.9 | na | na | na | na | na |

| D5-22 | 78.7 | 1.0 | na | na | na | na |

| D5-23 | 43.5 | na | na | na | na | na |

| D5-24 | 9.0 | na | na | na | na | na |

| D5-25 | 72.6 | 0.4 | na | 181.5 | na | na |

| Data Range | Fitting Region | Linear Fitting Equation | R2 | Fractionation Type Determination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0~130.40 m | Entire profile | y = 4.2546x − 112.98 | 0.8049 | Apparent overall correlation |

| 6.40~64.00 m | Active zone | y = 0.2193x − 77.559 | 0.0035 | No significant linear relationship |

| 64.00~96.85 m | Deep gas-poor zone | y = 5.3484x − 120.34 | 0.7997 | Strong linear correlation |

| Zone and Depth | Dominant Lithology | Key Geochemical Phenomenon | Proposed Migration/Fractionation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disturbed Zone 0~6.40 m | Silt | Sharp decrease in CH4 concentration. δ13C-CH4 not detected. | Gas escape due to high permeability and missing seal. Potential near-surface oxidation. |

| Active Zone 6.40~64.00 m | Silty clay (with a fine sand layer at 52.00–55.25 m) | δ13C-CH4 homogenization (~−75.6‰). Highly variable CH4 concentration. Anomalous enrichment (δ13C-CH4 = −57.4‰) within the fine sand layer. | Mixing-homogenization dominated by low-permeability clay. Anomaly Mechanism: Adsorption-fractionation window in the high-permeability sand layer. |

| Residual Zone 64.00~96.85 m | Silty-clay mixture | Strong linear δ13C-CH4 trend with depth (R2 = 0.92). Low CH4 concentration. | Rayleigh-type fractionation controlled by adsorption–desorption in a depleted, sealed reservoir. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, L.; Chen, Z.; Song, S.; Hu, T.; Lai, X. Investigating the Genesis and Migration Mechanisms of Subsea Shallow Gas Using Carbon Isotopic and Lithological Constraints: A Case Study from Hangzhou Bay, China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122372

Ji L, Chen Z, Song S, Hu T, Lai X. Investigating the Genesis and Migration Mechanisms of Subsea Shallow Gas Using Carbon Isotopic and Lithological Constraints: A Case Study from Hangzhou Bay, China. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122372

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Linqi, Zhongxuan Chen, Sheng Song, Taojun Hu, and Xianghua Lai. 2025. "Investigating the Genesis and Migration Mechanisms of Subsea Shallow Gas Using Carbon Isotopic and Lithological Constraints: A Case Study from Hangzhou Bay, China" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122372

APA StyleJi, L., Chen, Z., Song, S., Hu, T., & Lai, X. (2025). Investigating the Genesis and Migration Mechanisms of Subsea Shallow Gas Using Carbon Isotopic and Lithological Constraints: A Case Study from Hangzhou Bay, China. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122372