1. Introduction

In-service inspections and maintenance are important means to validate and recover the operational safety of infrastructures, assets, and vehicles. The need for in-service maintenance comes from inherent variabilities in environmental loads, modelling uncertainties, human errors in design and fabrication, discrepancies between as-built conditions and design, changes of operational modes, and others hazards that cannot be foreseen at the design stage. Although some of these factors can be considered in design via conservative safety factors, direct and indirect costs of conservative design usually outweigh its benefits. To reduce costs of conservative design, it is justified to adopt appropriate design factors and develop an in-service inspection programme that will validate operational safety and identify potential damages developed in service [

1].

Cracks are very common damages in welded structures that need to be inspected periodically and repaired if detected to ensure integrity of structures. Cracks are usually caused by cyclic fatigue loading under which cracks develop and grow until fracture occurs [

2,

3]. Crack propagation in fatigue-critical components can cause sudden rupture of the whole structural system, which represents a significant risk to safe operation and, in the event of occurrence, will have serious consequences, not only financially, but also environmentally and socially [

4].

Fatigue inspection and maintenance decision making is typically challenged by limited budgets for operational safety management and uncertain information about crack damage states in terms of location, occurrence time, extent, geometry, growth rate, etc., which are difficult to predict accurately due to sources of uncertainties in material properties, loads, modelling, etc. [

5,

6]. While inspection and maintenance can help increase operational safety and reduce risks, these benefits can be compromised by the uncertainties. The extent of risk mitigation is subjected to maintenance decisions such as inspection times, inspection method, repair criterions, and repair methods, which are further subjected to the uncertainties [

7]. The expected life cycle costs (LCCs, the sum of expected costs of inspection, repair, and failure) are also subjected to the uncertainties, as both the crack growth and inspection results are probabilistic at the inspection planning stage (i.e., at the beginning of service) [

8,

9]. Hence, maintenance decision-making models, which can consider various sources of uncertainties in a rational and consistent way, have the potential to reduce LCC while maintaining an acceptable risk level. Until recently, most studies on optimal maintenance decision making adopt the assumption that inspections are perfect, without considering inspection uncertainty explicitly [

10].

This paper addresses maintenance optimization by probabilistic modelling of crack growth and inspection quality. In practice, inspection accuracy and crack detection error are typically specified roughly in inspection instrument specifications, but without a statistical distribution to quantify the error. In this paper, focus is placed upon the uncertainty associated with inspection quality, and the quality of an inspection method is characterized by the detectable crack size

. Some standards provide guidelines on crack diagnostic uncertainty estimates, such as [

11]. Inspection uncertainty leads to probabilistic inspection results, which makes maintenance decision making difficult, together with probabilistic crack damage states. Reliability-based maintenance optimization approaches, with and without consideration of inspection uncertainty, have been developed taking into account corresponding PoD functions. The effects of inspection uncertainty on lifetime fatigue reliability have been presented, and based on this, a method to evaluate the effectiveness index of a planned inspection has been proposed.

2. Probabilistic Crack Growth

A fracture mechanics (FM) approach is employed for fatigue analysis. Fatigue failure is explained as the process of crack initiation, and crack growth until final fracture. The reason for this choice, i.e., as opposed to the S-N approach, is obvious. Herein, the damages that need to be inspected and controlled are fatigue cracks. An FM approach is suitable for crack growth prediction from an initial crack size to the finial critical crack size , while the objective of an S-N approach is to obtain a prediction on the overall fatigue life with a relatively high confidence level.

For welded structures, there are inevitable inclusions or initial flaws/cracks in materials introduced during the welding process, which decrease fatigue performance and shorten fatigue life. Due to the existence of initial flaws, it is often thought that the crack initiation stage is negligible compared with the crack growth stage. The relationship between crack growth rate and the stress intensity factor is given by the Paris law [

12,

13], formulated by Equations (1) and (2).

where

is time;

is crack size;

is number of cycles;

is the crack growth rate;

and

are material parameters;

is the stress intensity factor range;

is material fracture toughness;

is the threshold value for the stress intensity factor range;

is the geometry function; and

is the stress range.

If failure is defined by the crack depth reaching a critical size , then the crack growth life can be obtained by integration of Equation (1) from an initial crack size to

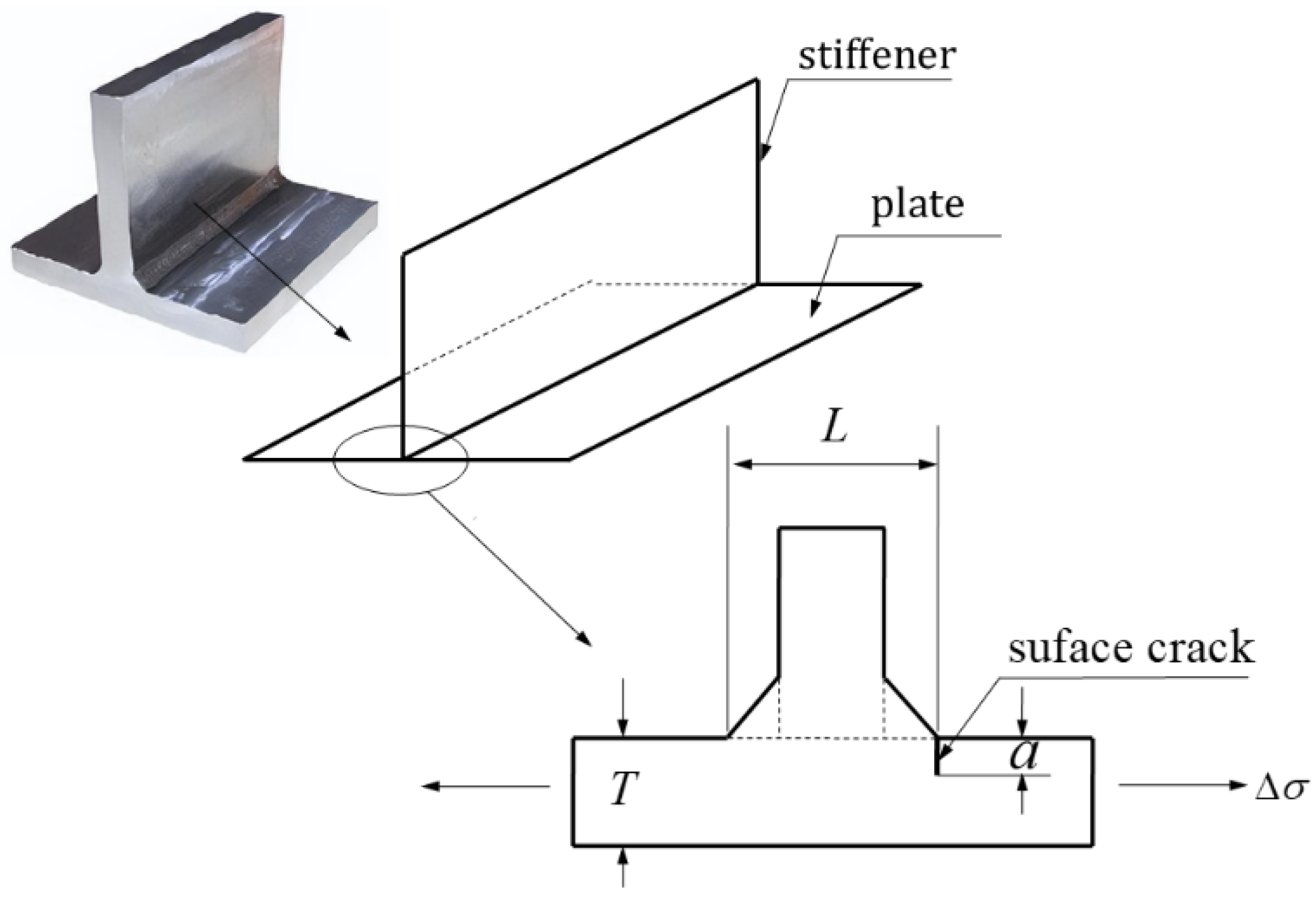

As an illustrative example, herein, a typical stiffened plate of a marine structure is examined (

Figure 1). The structure is typically found in offshore wind turbine platforms, offshore oil or gas platforms, ships, etc. Stiffeners are the most common structural components in ship structures, employed to increase the stability of plates of shells. However, crack initiation and growth along stiffeners are highly likely to occur during their lifetime due to the very large number of stiffeners in a ship. The integrity of the plate thus needs to be validated and recovered by periodical inspections and maintenance. The required service life

for the ship is typically 20 years. The frequency of wave loading is about 0.16 Hz, which is equal to approximately

cycles per year.

Fatigue resistance of the welded detail is given by an S-N curve given by Equation (3).

where

and

are the fatigue strength exponents,

and

are the fatigue strength coefficients, and

is the number of cycles exposed by the structural detail. The parameters for the S-N curve can be found in rules of ship classification societies. A fatigue design factor (FDF) of 8 is applied to a welded structural detail, which requires the maximal allowable equivalent stress range to be

. The plate thickness is

. The parameters are summarized in

Table 1.

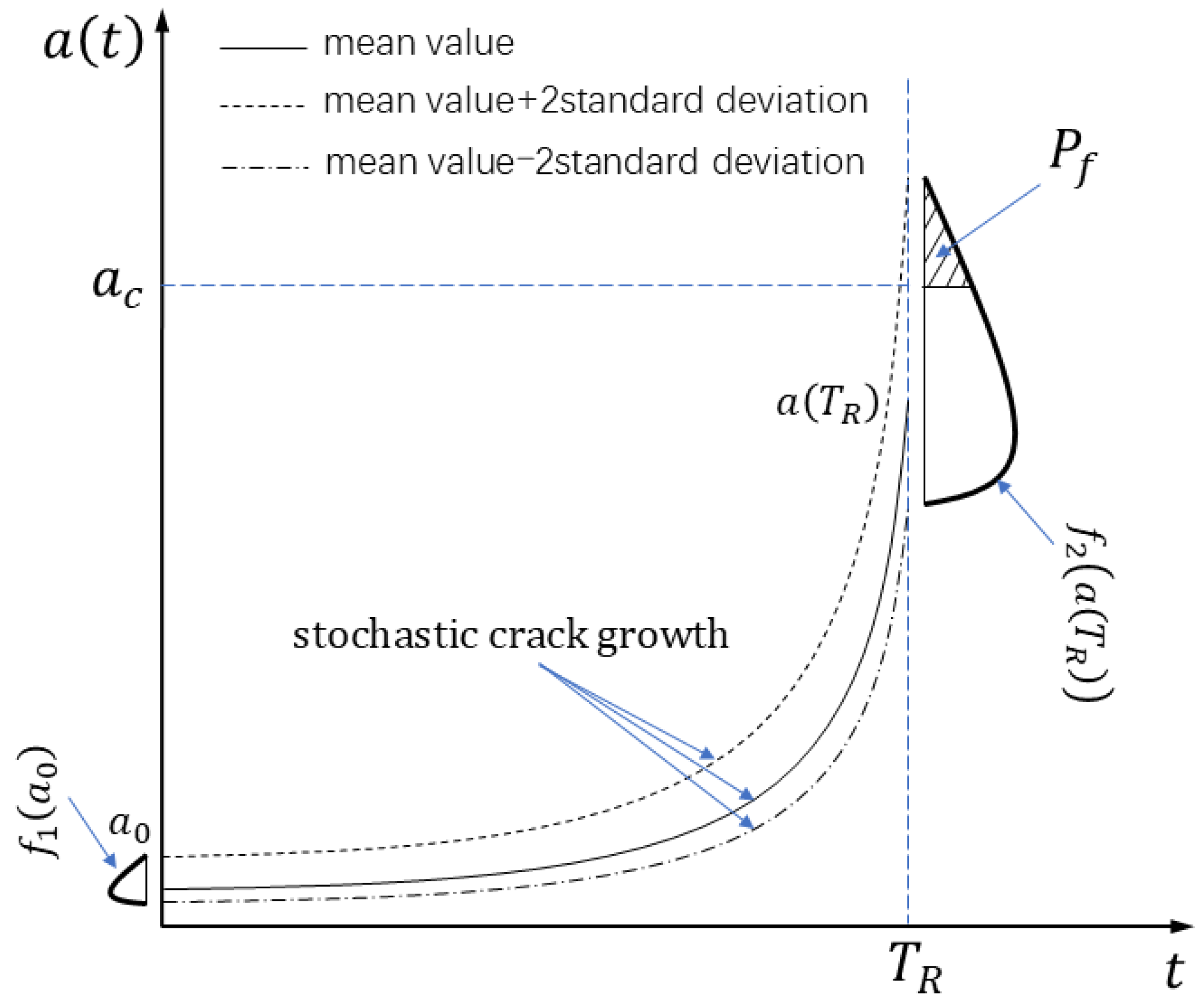

The crack growth prediction is subjected to several sources of uncertainty. It is believed that the accuracy of using the Paris law for crack growth prediction mainly depends on the accuracy of input parameters: initial crack size

, material parameter

, and stress range

Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of stochastic crack growth. In this paper, the initial crack size

and the crack growth rate

are modelled as variables. Uncertainties associated with the calculation of stress range

are modelled as an additional variable

The mean value and standard deviation (SD) for all variables are listed in

Table 2. The probability density function (PDF) of an exponential distribution and normal distribution can be found in a probability theory textbook [

14].

3. Maintenance Strategy

The adopted maintenance strategy is such that cracks detected by inspections will be repaired immediately, which is widely applied in engineering maintenance [

15,

16]. The repair method used in this paper is fixed, and out of the decision-making process. It is assumed that after repair, the crack size returns to its initial distribution. The latter is also widely adopted in the literature [

15,

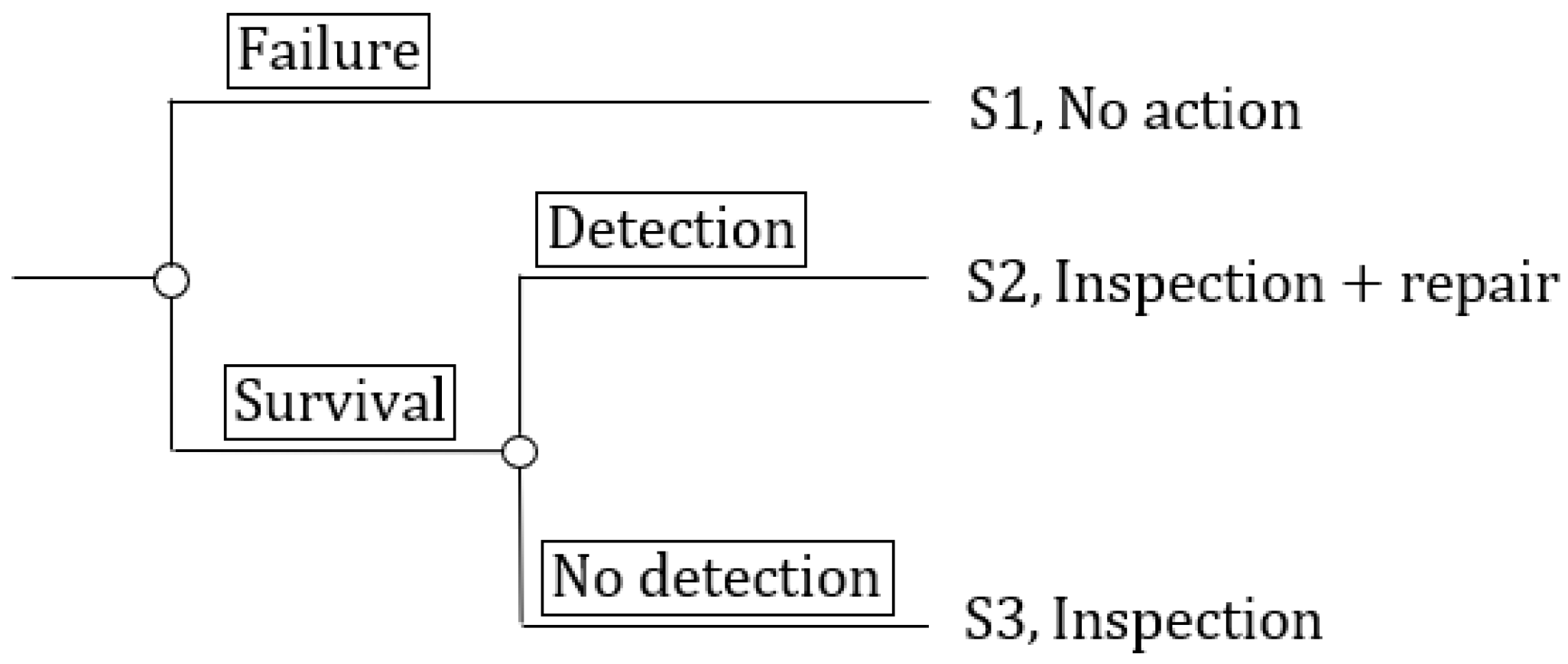

17]. This is a relatively reasonable assumption, as it considers the imperfect effect of repairing, i.e., there is still a failure probability associated with the repaired structure within the required service life. The decisions that need to be made include inspection methods and times in the lifetime, which affect lifetime fatigue reliability and expected LCC. Optimum inspection decisions are subjected to uncertain crack sizes and uncertain inspection results. Under the aforementioned maintenance strategy, there can be two possible inspection results: ‘detection’ and ‘no detection’. Therefore, at a planned inspection time, to be optimized, there can be three scenarios:

- -

S1: Failure has already occurred.

- -

S2: The structural detail has survived, and an inspection is carried out. Cracks are detected and repaired.

- -

S3: The structural detail has survived, and an inspection is carried out. There is no detection and thus no further action.

Figure 3 shows the decision tree analysis for one maintenance intervention. The small round circles in the figure are chance nodes. By decision tree analysis, the occurrence probability of each branch at the nodes can be calculated as well as the lifetime failure probability associated with each scenario.

4. Inspection Uncertainty

For maintenance, inspection actions are carried out to provide additional information on crack damage states, in addition to initial crack growth prediction with the Paris law, both of which form the basis for repair decision. As for fatigue crack detection, commonly adopted inspection methods are (close) visual inspection and NDT methods, e.g., liquid penetrant, ultrasonic, magnetic particle, and acoustic emission inspection methods.

Crack detection by NDT methods is inherently probabilistic, as there are many factors that can influence inspection results. Sometimes, existing cracks cannot be identified. Conversely, a positive indication may be false due to the absence of a crack. It is also often found that an existing crack can be detected by one inspector but can be missed by other inspectors. NDT results depend on the reliability of the specific instrument–human system. Generally, the following factors can influence the chance of crack detection:

- -

Crack characteristics (sizes, shape, location, etc.);

- -

The reliability of instrumentation;

- -

The environment where inspection is carried out;

- -

Inspection procedure;

- -

Human factors associated with the inspector.

To utilize information provided by inspection results, the reliability of the instrument–human system and confidence level on the inspection results must be adequately demonstrated in terms of the level of accuracy in which the inspection results can represent the true crack characteristics. The reliability of an inspection method is often characterized by a PoD curve. PoD is defined as the probability that a given crack of a fixed size can be detected by a given inspection method.

PoD curves for inspection methods are traditionally obtained by inspection experiments on structural details of a range of crack sizes. Based on inspection results, an appropriate function is assumed for the PoD curve, and parameters of the function are estimated by statistical methods. The confidence range on the PoD can also be specified based on estimated parameters. The experimental approach is typically very expensive and time-consuming as there are so many factors that can affect the probability of detection. Nowadays, simulation approaches are also developed to obtain PoD curves [

18,

19,

20]. In this paper, the exponential PoD function given by Equation (4) is employed. The function is the cumulative density function of an exponential distribution.

where

is crack size and

is the mean detectable crack size.

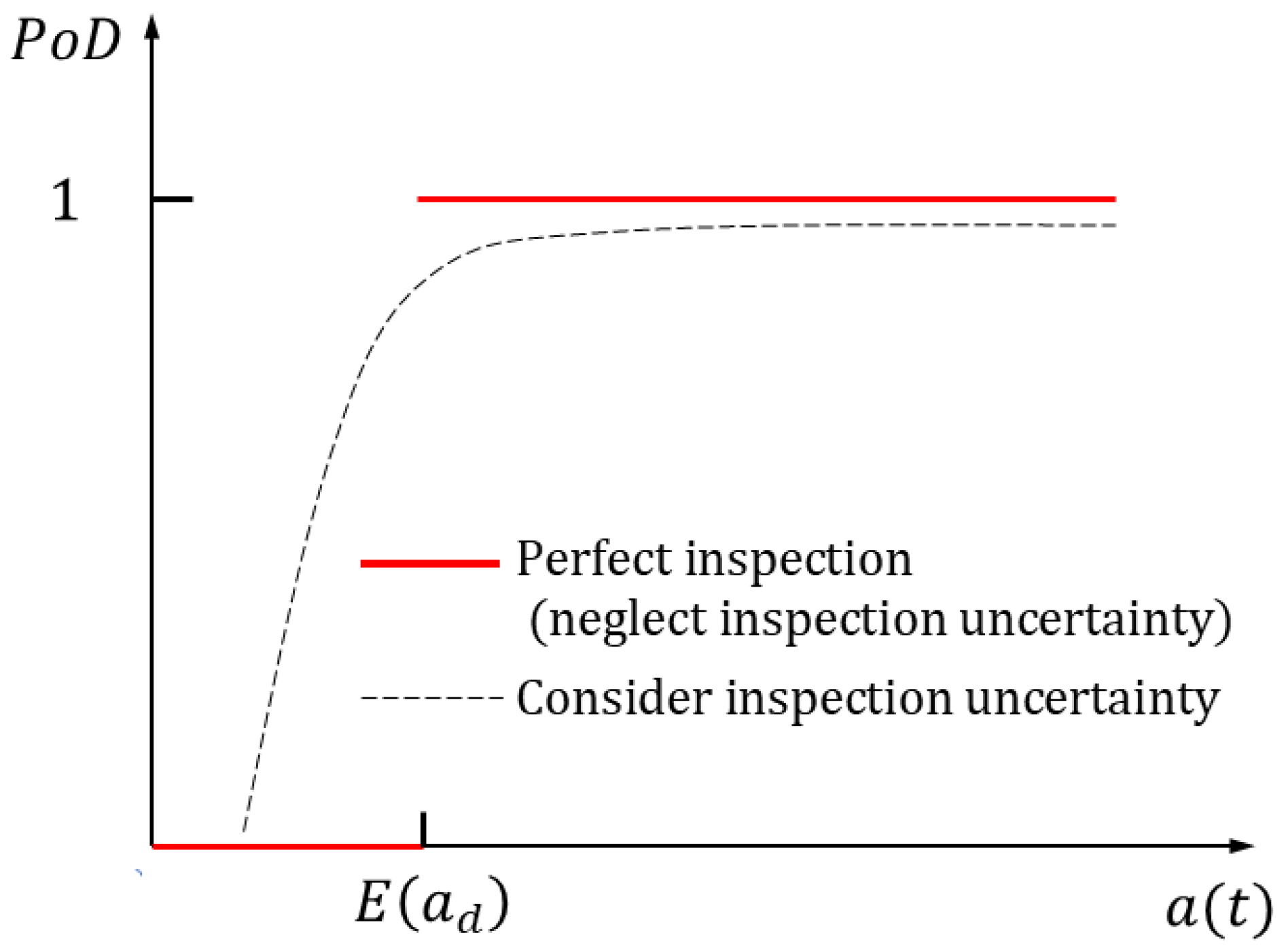

Using this function, uncertainties associated with inspection quality are taken into account by modelling the detectable crack size of an inspection method as a variable. The PoD function is actually the cumulative density function (CDF) of the variable .

To investigate the influence of inspection uncertainty on optimum maintenance decisions, comparative studies are carried out while considering and neglecting inspection uncertainty in maintenance optimization (two scenarios). Two different kinds of PoD functions are applied, as shown schematically in

Figure 4. The first is the above exponential PoD function (Equation (4)), which provides a means to consider inspection uncertainty by predicting a detection probability for any given crack size. The other PoD function is defined as below.

Equation (5) assumes that cracks equal to or larger than will be detected with a probability of 1, which means perfect detectability for those cracks. Equation (5) also implies that the detectable crack size of an inspection method is a constant value .

5. Fatigue Reliability

5.1. Initial Reliability

Herein, failure of the structural detail is defined as the occurrence of a through-thickness crack, i.e., the critical crack size is equal to plate thickness (Equation (6)).

The limit state function is given by Equation (7).

where

signifies fracture failure. The critical crack size

is set as equal to the plate thickness

, as failure is defined as the occurrence of a through-thickness crack. Failure probability

and reliability index

are given by Equations (8) and (9), respectively.

where

is the cumulative distribution function of a standard normal distribution and can be found in a probability theory textbook [

14].

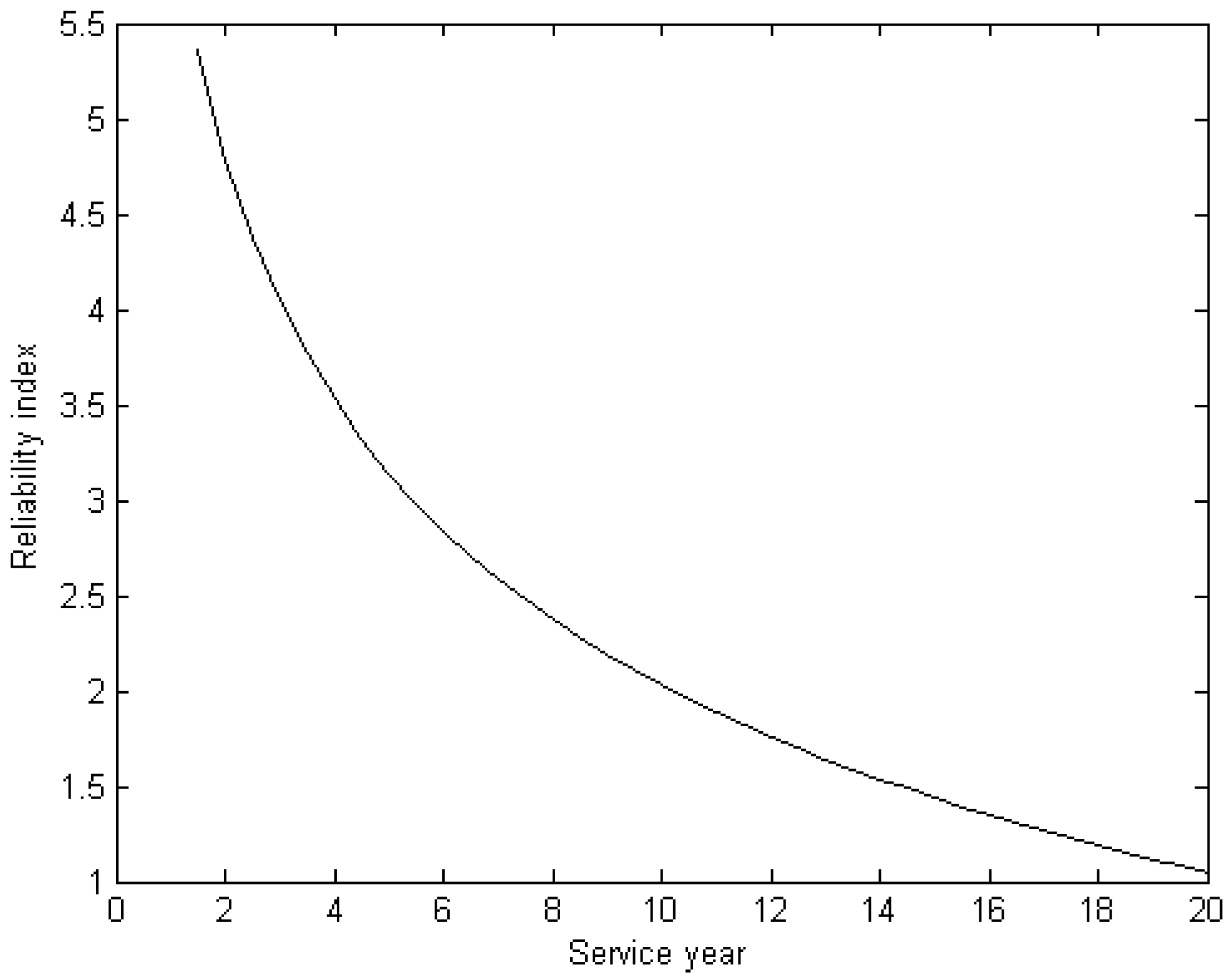

Based on Equation (7), the initial failure probability and reliability index without maintenance at each service year can be calculated by reliability methods. In this paper, Monte Carlo simulation is adopted. Each of the random variables in

Table 2 is simulated by

samples by a statistical toolbox, and then failure probability is calculated based on Equations (7) and (8). The reliability index is calculated by Equation (9). The decline in reliability index with service year is shown by

Figure 5. We check and believe that all generated data are correct and reliable. It can be seen that the reliability index at the end of the required service life (lifetime reliability index) is

. The reliability is low, and thus in-service inspection and maintenance actions are needed.

5.2. Reliability with Planned Maintenance

Planned maintenance helps increase lifetime fatigue reliability. Based on the decision tree analysis of

Figure 3, if cracks were detected, they are repaired in time, and lifetime failure probability will decrease. If the inspection result were no detection, lifetime failure probability would also decrease, taking the additional information of no detection into account. Based on

Figure 3, lifetime failure probability with one planned maintenance intervention can be calculated by Equation (10).

where

is the planed inspection time,

is the probability of scenario

occurring, and

is the failure probability condition that scenario

occurs.

Equation (11) gives the updated lifetime reliability index.

6. Effectiveness of Imperfect Inspection

Three inspection methods have been applied to investigate the effect of inspection quality: magnetic particle inspection (MPI), close visual inspection (CVI), and visual inspection (VI). The mean detectable crack size

for the inspection methods is based on Madsen et al. [

17] and Dong and Frangopol [

13]. With each inspection method, two PoD functions as described in

Section 4 have been adopted, and the max reliability indexes corresponding to the PoD functions have been derived. Equation (12) defines the effectiveness index of a planned inspection.

where

is the max lifetime reliability under the scenario ‘inspection uncertainty’, i.e., inspection uncertainty is considered by using Equation (4);

is the max lifetime reliability under the scenario ‘perfect inspection’, i.e., inspection uncertainty is not considered, and Equation (5) is used.

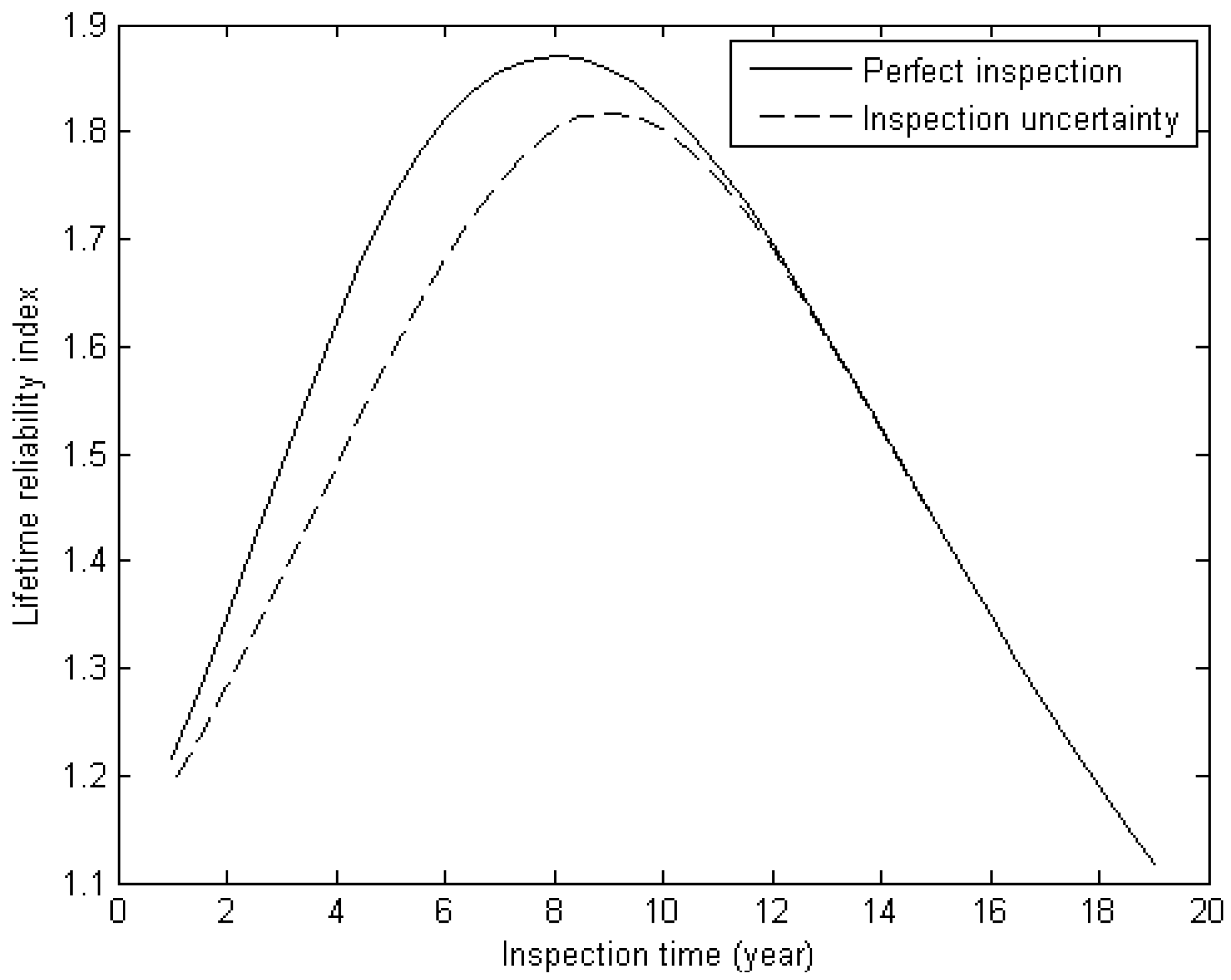

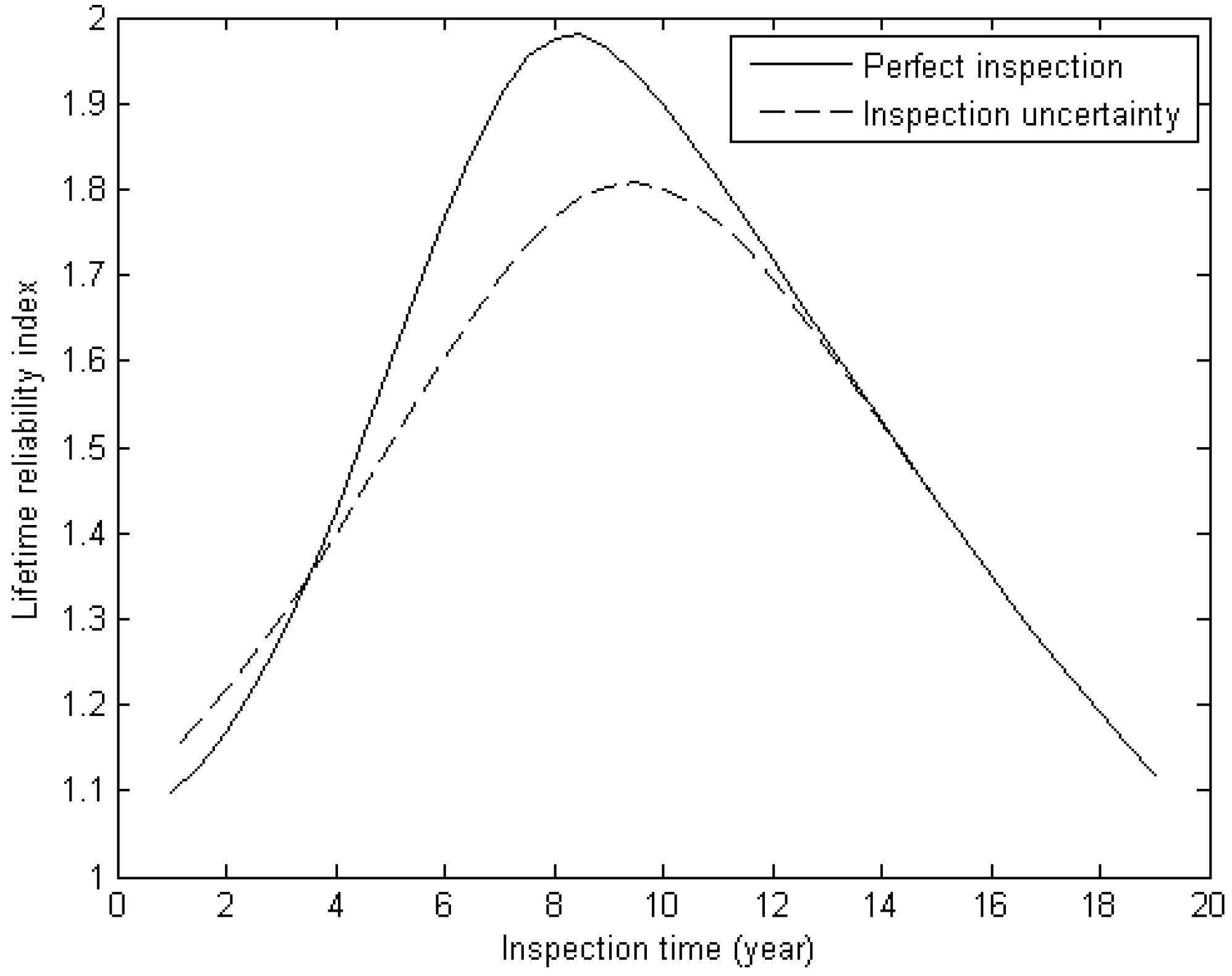

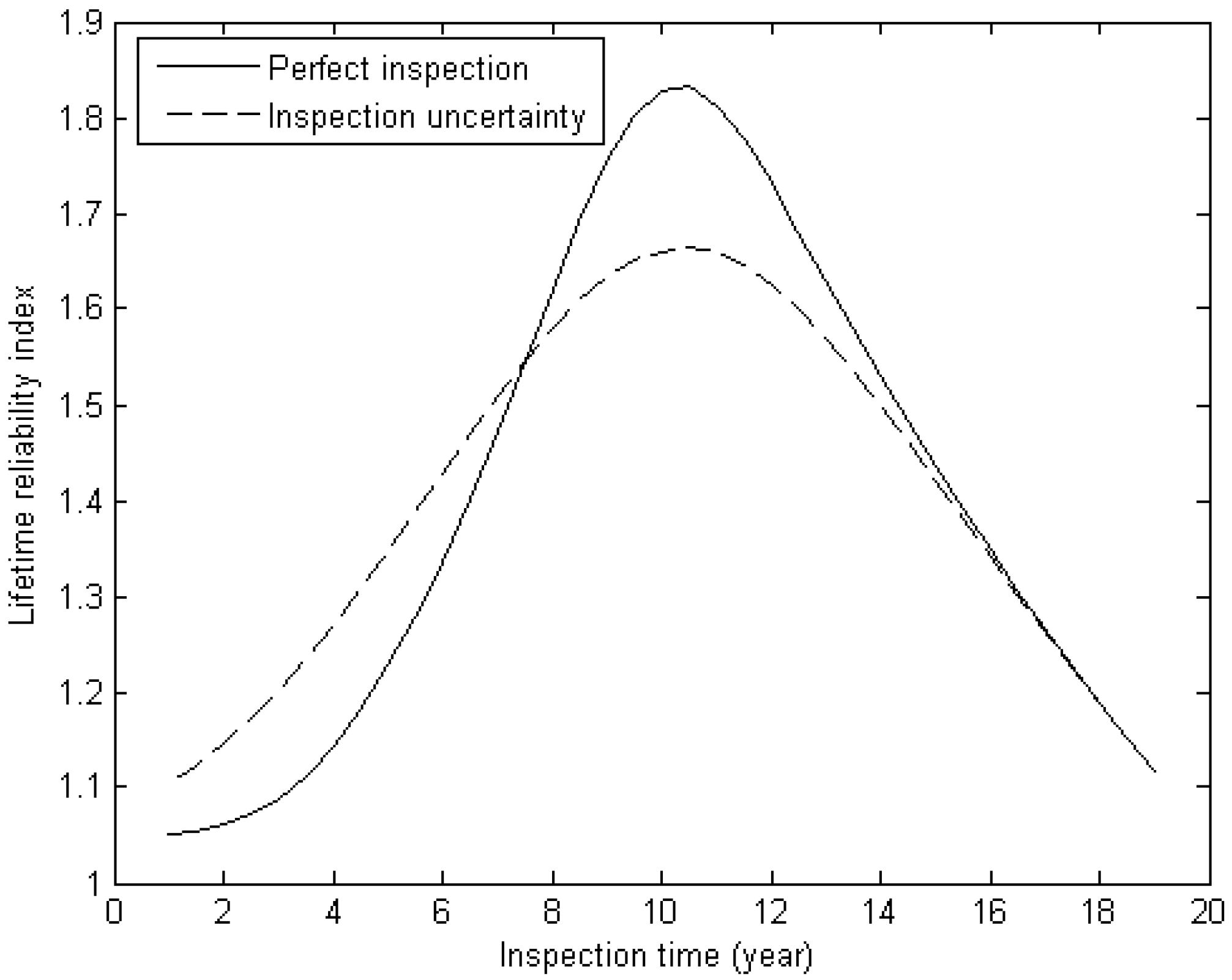

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 give the lifetime reliability index against planned inspection time for the three inspection methods under investigation.

Table 3 summarizes the results. In the table,

is mean value of the dateable crack size of an inspection method,

is the max reliability index while neglecting inspection uncertainty;

is the max reliability while considering inspection uncertainty; and

is the effectiveness index of a planned inspection. Based on the figures and table, it is concluded that the max lifetime reliability index (

and

) generally decreases when inspection uncertainty is considered for all the three inspection methods. However, if an inspection is scheduled at the late stage of service life, inspection uncertainty has little influence on the lifetime reliability index. The lifetime reliability index can be higher when inspection uncertainty is considered than neglected, if CVI or VI is adopted, and an inspection is scheduled at the early stage of service life. The effectiveness index of a planned inspection increases with the decrease in

. When considering inspection uncertainty, the effectiveness index of a planned inspection adopting MPI is higher than adopting CVI and VI.

7. Two Planned Inspections

In this section, effects of inspection uncertainty on reliability are investigated when two inspections are planned during the whole service life and with each interval.

Table 4 shows the results when the service life is 20 years and two inspections are planned to be implemented in the 7th and 14th year. It can be seen that compared with one inspection planned in

Table 3, the reliability level (

) increases when two inspections are planned, regardless of what inspection method is used. The inspection method effectiveness index (

) is equal to 0.987, 0.939, and 0.880 when MPI, CVI, and VI are employed, respectively. When two inspections are planned compared with one inspection, the effectiveness indexes of MPI and CVI increase while the effectiveness indexes of VI decrease. This means that we should pay attention to the effects of uncertainty associated with the inspection method with worse quality (such as VI) when more inspections are planned.

Table 5 shows results when the service life (

) is 15 years and two inspections are planned to be implemented in the 5th and 10th years (

,

).

Table 6 shows the results when the service life is 30 years and two inspections are planned to be implemented in the 10th and 20th years.

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 indicate that the effect of inspection interval on the effectiveness index is weak.

8. Life Cycle Costs and Repair Costs

In this section, the effects of inspection uncertainty on expected life cycle costs (

) and repair costs (

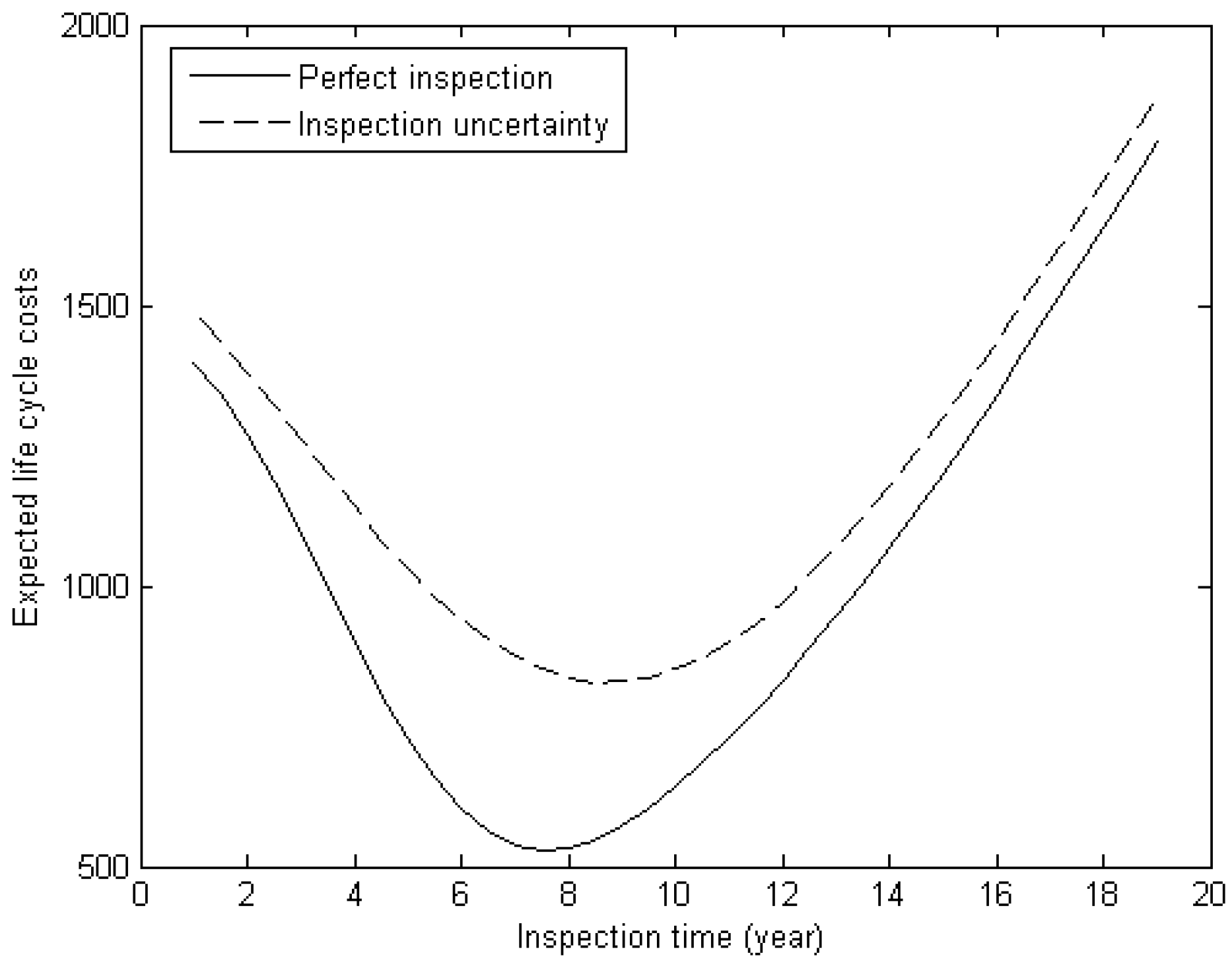

) are studied. It is considered that one inspection is planned during the whole service life and CVI is used. It is assumed that the costs of failure, one repair, and one inspection are 10,000, 1000, and 1 unit, respectively.

Figure 9 shows life cycle costs when inspection uncertainty is neglected or considered. It clearly shows that the effect of inspection uncertainty on expected life cycle costs is noticeable. Specifically, when actual inspection uncertainty is considered, expected life cycle costs increase significantly.

Table 7 shows the minimum expected life cycle costs and repair costs when the inspection is planned to be implemented at the optimal time. When actual inspection uncertainty is considered, the minimum expected life cycle costs and repair costs are 1.567 and 1.690 times what they would be if inspection uncertainty were neglected. The increase in life cycle costs is mainly due to the increase in repair costs, which is attributed to a higher probability of repair (

). In summary, the effects of inspection uncertainty on expected life cycle costs and maintenance costs are more noticeable compared to the reliability index.

9. Conclusions

Maintenance optimization is important, for engineering structures with a substantial number of fatigue-prone details and locations, in terms of increasing operational reliability and decreasing repair costs. The main challenge for maintenance decision making is uncertain damage states in service life. In this regard, in-service inspections are assigned to gather information on damage states. However, there is an unavoidable uncertainty associated with an inspection method, which may affect maintenance optimization.

Unlike most of the studies without considering inspection uncertainty [

10], in this paper, the influence of inspection uncertainty on reliability-based maintenance optimization has been studied by explicitly modelling the uncertainties associated with crack growth rate, initial crack size, stress calculation, and inspection quality. The novelty of this study lies in two aspects. On one hand, the inspection quality of an inspection method is characterized by the detectable crack size. A new PoD function has been proposed for perfect inspection quality, i.e., without a consideration of inspection uncertainty. The PoD function serves as a comparison to the PoD function that models the inspection quality as a variable. On the other hand, the effectiveness index of a planned inspection has been defined based on the max lifetime reliability index while considering and neglecting inspection uncertainty.

It has been shown that the max lifetime reliability index generally deceases when inspection uncertainty is considered. However, inspection uncertainty may have little influence on the lifetime reliability index, depending on the planned inspection time. The effectiveness index of a planned inspection increases with the decrease in the mean detectable crack size (). When actual inspection uncertainty is considered, expected life cycle costs and maintenance costs increase notably.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.Z.; Methodology, G.Z.; Software, G.Z.; Validation, G.Z., L.L. and J.L.; Formal analysis, G.Z.; Investigation, G.Z.; Resources, L.L.; Data curation, J.L.; Writing—original draft, G.Z.; Writing—review & editing, G.Z., L.L. and J.L.; Visualization, G.Z.; Supervision, G.Z.; Project administration, G.Z., L.L. and J.L.; Funding acquisition, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding from the Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (No. 2023A1515240057) and Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Bureau (No. JCYJ20240813094508012) is greatly appreciated.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moan, T. Life-cycle assessment of marine civil engineering structures. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2011, 7, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, T.; Yang, B.; Xiao, S.; Yang, G. Failure analysis of stress corrosion cracking in welded structures of aluminum alloy metro body traction beam in service. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 163, 108564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, W. Fatigue analysis of welded joints: State of development. Mar. Struct 2003, 16, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zou, G. A novel computational approach for assessing system reliability and damage detection delay: Application to fatigue deterioration in offshore structures. Ocean. Eng 2024, 297, 117023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, Y. Efficient risk-based inspection framework: Balancing safety and budgetary constraints. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe 2025, 253, 110519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondini, F.; Frangopol, D.M. Life-Cycle Performance of Deteriorating Structural Systems under Uncertainty: Review. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 142, F4016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventikos, N.P.; Sotiralis, P.; Drakakis, M. A dynamic model for the hull inspection of ships: The analysis and results. Ocean. Eng 2018, 151, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacconi, S.; Ierimonti, L.; Venanzi, I.; Ubertini, F. Life-cycle cost analysis of bridges subjected to fatigue damage. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2021, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Frangopol, D.M.; Soliman, M. Generalized Probabilistic Framework for Optimum Inspection and Maintenance Planning. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, B.; Scarf, P.A. A review on maintenance optimization. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 285, 805–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNVGL-RP-C210; Probabilistic Methods for Planning of Inspection for Fatigue Cracks in Offshore Structures. DNL GL Standard: Oslo, Norway, 2015.

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.; Shen, C.; Zhao, X.-L. Study on fatigue behavior of butt-welded high-strength steel connections with surface cracks. Thin Walled Struct. 2024, 200, 111888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Garbatov, Y.; Guedes Soares, C. Review on uncertainties in fatigue loads and fatigue life of ships and offshore structures. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 264, 112514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. Probability Theory; Courier Corporation: North Chelmsford, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, M.; Frangopol, D.M.; Mondoro, A. A probabilistic approach for optimizing inspection, monitoring, and maintenance actions against fatigue of critical ship details. Struct. Saf. 2016, 60, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdebenito, M.A.; Schuëller, G.I. Design of maintenance schedules for fatigue-prone metallic components using reliability-based optimization. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2010, 199, 2305–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.; Torhaug, R.; Cramer, E. Probability-based cost benefit analysis of fatigue design, inspection and maintenance. In Proceedings of the Marine Structural Inspection, Maintenance and Monitoring Symposium, Arlington, VA, USA, 18–19 March 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, M.; Wedgwood, F.; Burch, S. Modelling of NDT Reliability (POD) and applying corrections for human factors. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on NDT (ECNDT), Copenhagen, Denmark, 26–29 May 1998; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Volker, A.; Dijkstra, F.; Terpstra, S.; Heerings, H.; Lont, M. Modeling of NDE reliability: Development of a POD generator. In Proceedings of the 16th World Conference on Nondestructive Testing, Montreal, QC, Canada, 31 August–3 September 2004; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, M.; Burch, S.; Lilley, J. Review of models and simulators for NDT reliability (POD). Insight Non Destr. Test. Cond. Monit. 2009, 51, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A welded detail in a stiffened plate in a marine structure.

Figure 1.

A welded detail in a stiffened plate in a marine structure.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of stochastic crack growth and failure probability ( is the probability density function of ; is the probability density function of crack size at the end of the service life ; is the failure probability within the required service life ).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of stochastic crack growth and failure probability ( is the probability density function of ; is the probability density function of crack size at the end of the service life ; is the failure probability within the required service life ).

Figure 3.

Decision tree analysis for one maintenance intervention.

Figure 3.

Decision tree analysis for one maintenance intervention.

Figure 4.

Probability of detection (PoD) curves (‘Inspection uncertainty’ and ‘Perfect inspection’ mean that inspection uncertainty is considered and not considered, respectively).

Figure 4.

Probability of detection (PoD) curves (‘Inspection uncertainty’ and ‘Perfect inspection’ mean that inspection uncertainty is considered and not considered, respectively).

Figure 5.

Decline in reliability index with service year.

Figure 5.

Decline in reliability index with service year.

Figure 6.

Lifetime reliability index ( and ) against inspection time (MPI).

Figure 6.

Lifetime reliability index ( and ) against inspection time (MPI).

Figure 7.

Lifetime reliability index ( and ) against inspection time (CVI).

Figure 7.

Lifetime reliability index ( and ) against inspection time (CVI).

Figure 8.

Lifetime reliability index against inspection time (CI).

Figure 8.

Lifetime reliability index against inspection time (CI).

Figure 9.

Expected life cycle costs against inspection time.

Figure 9.

Expected life cycle costs against inspection time.

Table 1.

Design parameters for the welded detail.

Table 1.

Design parameters for the welded detail.

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|

| Year | 20 |

| Cycle | |

| - | 11.855 |

| - | 15.091 |

| mm | 25 |

| MPa | 17.28 |

| - | 3 |

| - | 5 |

Table 2.

Variables for reliability analysis (

is the detectable crack size of an inspection introduced in

Section 4).

Table 2.

Variables for reliability analysis (

is the detectable crack size of an inspection introduced in

Section 4).

| Variable | Distribution | Unit | Mean | SD |

|---|

| Exponential | mm | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Normal | - | −12.74 | 0.11 |

| Normal | - | 1.00 | 0.30 |

| Exponential | mm | | |

Table 3.

Effectiveness index of a planned inspection.

Table 3.

Effectiveness index of a planned inspection.

| Method | | | | |

|---|

| MPI | 0.89 mm | 1.871 | 1.818 | 0.972 |

| CVI | 2.00 mm | 1.979 | 1.807 | 0.913 |

| VI | 4.35 mm | 1.832 | 1.664 | 0.908 |

Table 4.

Effectiveness index of two planned inspections ( = 20, = 7, = 14).

Table 4.

Effectiveness index of two planned inspections ( = 20, = 7, = 14).

| Inspection Method | MPI | CVI | VI |

|---|

| 2.389 | 2.466 | 2.333 |

| 2.358 | 2.315 | 2.054 |

| 0.987 | 0.939 | 0.880 |

Table 5.

Effectiveness index of two planned inspections ( = 15, = 5, = 10).

Table 5.

Effectiveness index of two planned inspections ( = 15, = 5, = 10).

| Inspection Method | MPI | CVI | VI |

|---|

| 2.641 | 2.720 | 2.563 |

| 2.589 | 2.523 | 2.221 |

| 0.980 | 0.928 | 0.867 |

Table 6.

Effectiveness index of two planned inspections ( = 30, = 10, = 20).

Table 6.

Effectiveness index of two planned inspections ( = 30, = 10, = 20).

| Inspection Method | MPI | CVI | VI |

|---|

| 2.132 | 2.224 | 2.126 |

| 2.087 | 2.068 | 1.842 |

| 0.979 | 0.930 | 0.866 |

Table 7.

Effects of inspection uncertainty on expected life cycle costs and repair costs.

Table 7.

Effects of inspection uncertainty on expected life cycle costs and repair costs.

| Scenario | Perfect Inspection | Inspection Uncertainty | Ratio |

|---|

| 529.0 | 828.9 | 1.567 |

| 272.4 | 460.4 | 1.690 |

| 0.272 | 0.460 | 1.690 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).