Analysis of Critical Control Points of Post-Harvest Diseases in the Material Flow of Nam Dok Mai Mango Exported to Japan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

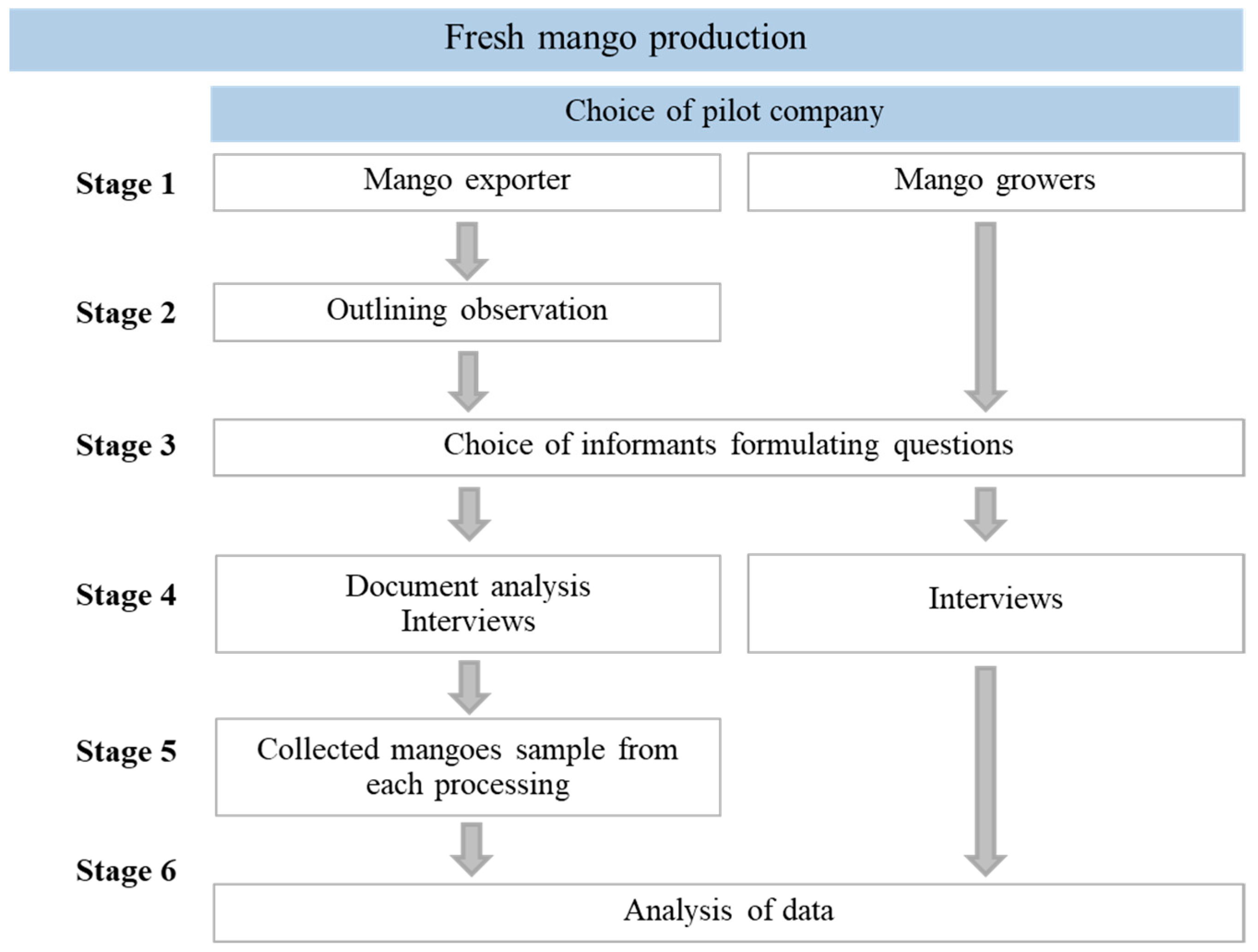

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Choices of Pilot Company (Stage 1)

2.2. Outlining Observation (Stage 2)

2.3. Choices of Informants and Formulating Questions (Stage 3)

2.4. Interviews and Document Analysis (Stage 4)

2.4.1. Mango Growers

2.4.2. Exporter

2.5. Collection of Mangoes for Disease Evaluation (Stage 5)

- a = number of all infected fruit in each treatment

- b = number of all fruit in each treatment

2.6. Analysis of Data (Stage 6)

3. Results and Discussion

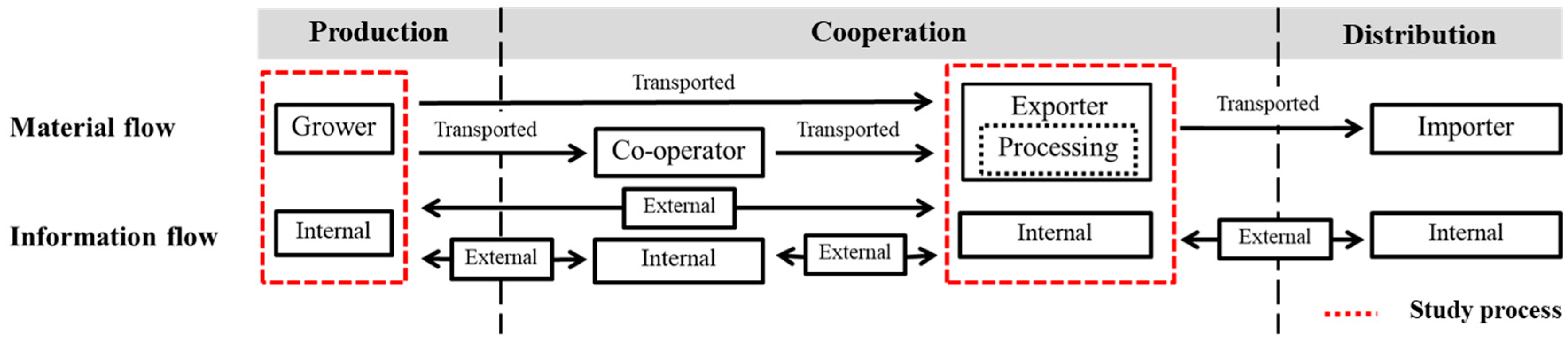

3.1. Supply Chains of ‘Nam Dok Mai’ Mango Exported from Thailand to Japan

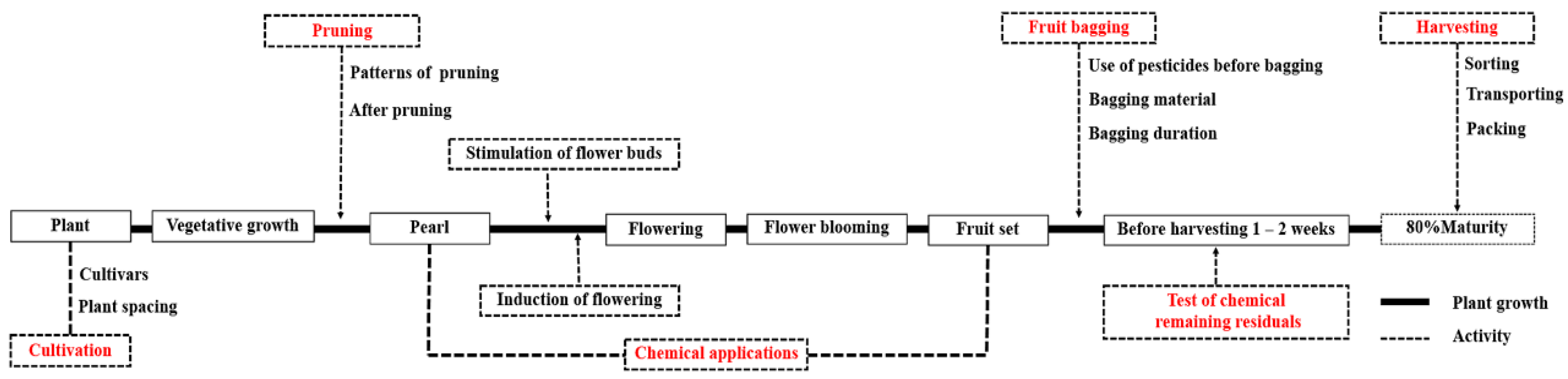

3.2. Mango Process Mapping and Disease Risk Assessment for Farms

- (a)

- Cultivation: Mango growers grew both sub-cultivars of ‘Nam Dok Mai’ mango, namely ‘Nam Dok Mai’ and ‘Nam Dok Mai’, for 80% of total planted mangoes while the remaining 20% were other varieties (Table 2). This implies that ‘Nam Dok Mai’ mango is the most favored one, although the production of mango for export has several compulsory requirements including GAP certification, the limitation of chemical residues, and the absence of defects (physical damage, insect and disease symptoms) and disorders. Thus, the production must follow good procedures of cultivation to produce high quality products. The typical price of ‘Nam Dok Mai’ mango in terms of the export standard is approximately 3–5 times higher than other cultivars, leading to high levels of interest from growers. However, in terms of sub-cultivars, ‘Nam Dok Mai Sithong‘ mango has been promoted to replace ‘Nam Dok Mai No. 4’ mango for export mainly due to its tolerance against anthracnose diseases [15]. The former is a new selection showing bright yellow fruit whereas the latter is an older cultivar with very good flavor. From our observation of mangoes from 5 different orchards in the Phetchabun province, it was seen that the percentage of infection for ripe ‘Nam Dok Mai No. 4’ mangoes was 73.3% while it was only 52.7% for ripe ‘Nam Dok Mai Sithong’ mangoes on day 11 of incubation (Table 3). This confirms the varying effect of the disease of the cultivars. Interestingly, there were 23–40% of ‘Nam Dok Mai No. 4’plants still planted in the farms, which were processed for export. This means that mango growers were not aware of the crucial factor of anthracnose disease infection. This is the first risk point in the material flow that could increase post-harvest disease incidence at the destination or during retail display.

- (b)

- Branch pruning: Pruning is a necessary first step in the management of flowering for the next season. It ensures not only a uniform flush of tree growth throughout the canopy but also the removal of the previous season’s flowering and fruiting panicles. In particular, dead or diseased wood is removed to decrease accumulated disease. After tip pruning, the diseased wood must be removed from the orchard and destroyed (GAP guide). All growers follow the branch pruning program strictly. However, 93.3% of growers did not remove tips and 66.3% did not remove fruit rot from the mango trees after pruning (Table 4) mainly due to a lack of labor. The tips were crumbed and propped under the tree instead. The diseases thus accumulate in the production field year after year and it becomes difficult to clean or eliminate the diseases during the next production year. This is the second crucial step for field production management in terms of induction risks of post-harvest diseases.

- (c)

- Chemical applications: Chemicals used to prevent diseases infections among mango trees and fruit were mostly applied during vegetative flushing (between the leaf pearl and fruit set stages) prior to fruit bagging. The fungicides used by mango growers included Prochloraz, Propinep, Mancozeb, and Azoxystrobin. Although the GAP guide suggests that chemicals be used when diseases or insects appear, chemicals were ordinarily used every 10–14 days as a precaution by most growers (Table 5). The interviews showed that more than 40% of growers did not wait until they found anthracnose disease damage but applied fungicides every 10 days. This implies that this process is important to prevent disease infection and accumulation. Nevertheless, excessive applications of chemicals increase the capital required for mango production.

- (d)

- Fruit bagging: This step is essential to protect fruit skin not only from physical damage but also from insect invasion and disease infection [18]. Furthermore, for ‘Nam Dok Mai No. 4’ mango, this process induces the yellow skin color [19]. All growers use the Shun Fong® bag (laminated bag with carbon paper inside and brown paper outside) for mango bagging for export. The appropriate duration to start bagging mangoes was between 45–55 days after flowering (DAF) for ‘Nam Dok Mai No. 4’ mango and between 60–70 DAF for ‘Nam Dok Mai Sithong’ mango. The GAP guide suggests bagging mangoes during 40–50 DAF in general. Of the growers, 80% followed the bagging process mostly 1 day after pesticide application (Table 5). After fruit bagging, growers significantly reduced chemical use and fungicides were applied only when disease damage was found. This is another crucial step to reduce fruit bruising and post-harvest disease infection. However, it is a cause for concern that above 30% of growers reused bagging material more than 2 times, which can lead to an accumulation of diseases.

- (e)

- Chemical residual checking: One or two weeks before harvesting, mangoes were randomly sampled by exporter staff to check for chemical residues. Chlorpyrifos must remain less than 0.05 mg·L−1 on fruit for it to qualify for Japanese markets. Once chemical residue levels were approved, the exporter staff then scheduled the harvest date of mangoes based on 80% of maturation time.

- (f)

- Harvesting: Mangoes in the Shun Fong® bag were harvested in the morning. The harvested fruit was transported to the grower’s packing house or to the co-operator’s premises and the paper bags were removed. If the bags were removed in the field, mangoes usually displayed defects such as scratches during transportation, which lead to anthracnose infection [20]. Mangoes without defects were sorted by the exporter staff. The selected fruit was covered with a foam net before being placed in plastic baskets and transported to the exporter’s packing house. Mangoes not meeting the standard were, on the other hand, sold to domestic markets.

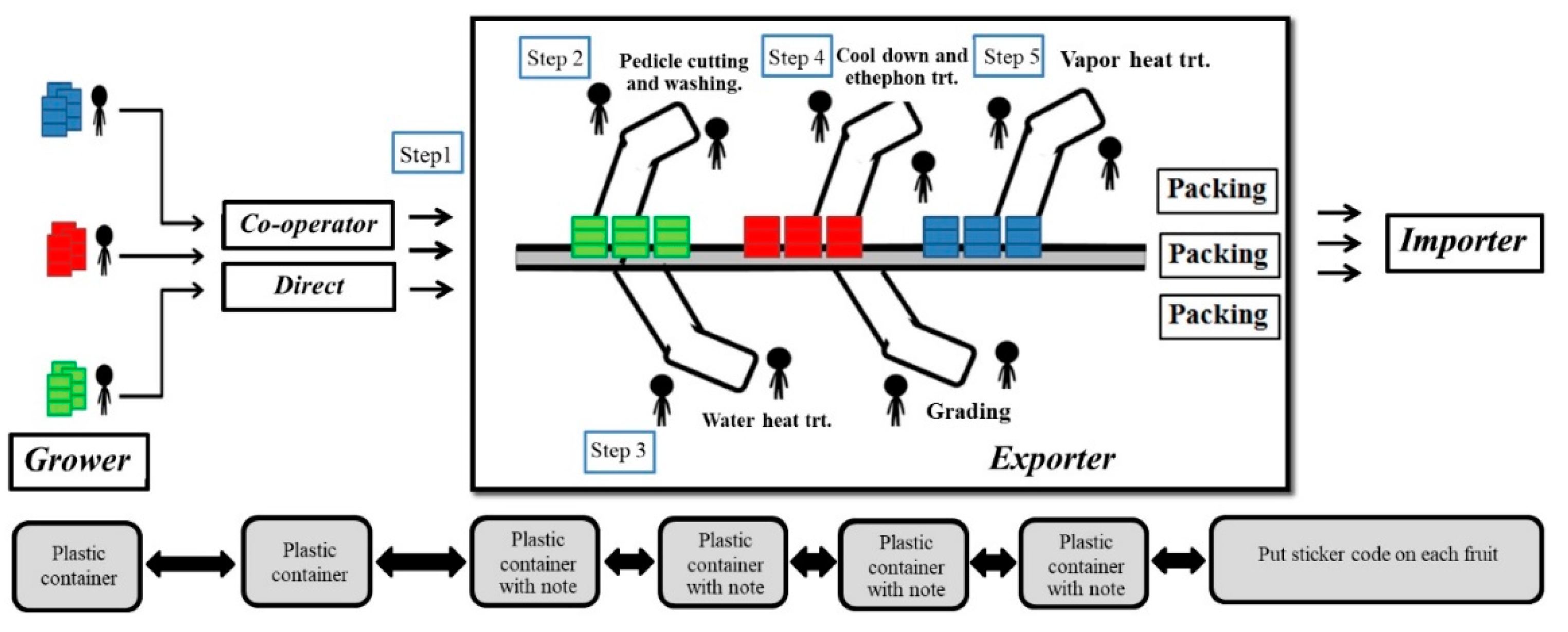

3.3. Mango Process Mapping in the Packing House of the Exporter

- (a)

- Mango grower’sorchard: ‘Nam Dok Mai’ mangoes are produced in Thailand all year round, starting in the east during November–April, Central Thailand during January–May, the north during May–June, the northeast during August–October, and the west during September–December. The exporter collected mangoes using two ways: direct transportation from growers and collection from co-operators. However, whether direct or indirect ways were used, the growers’ information and relevant codes were officially issued by the exporter staff. On the harvest date, the exporter staff were ready at farms to select, grade (280–450 g), pack, and transport mangoes to the packing house of the exporter. Mangoes were transported at night and generally arrived at the packing house early in the morning depending on the distance.

- (b)

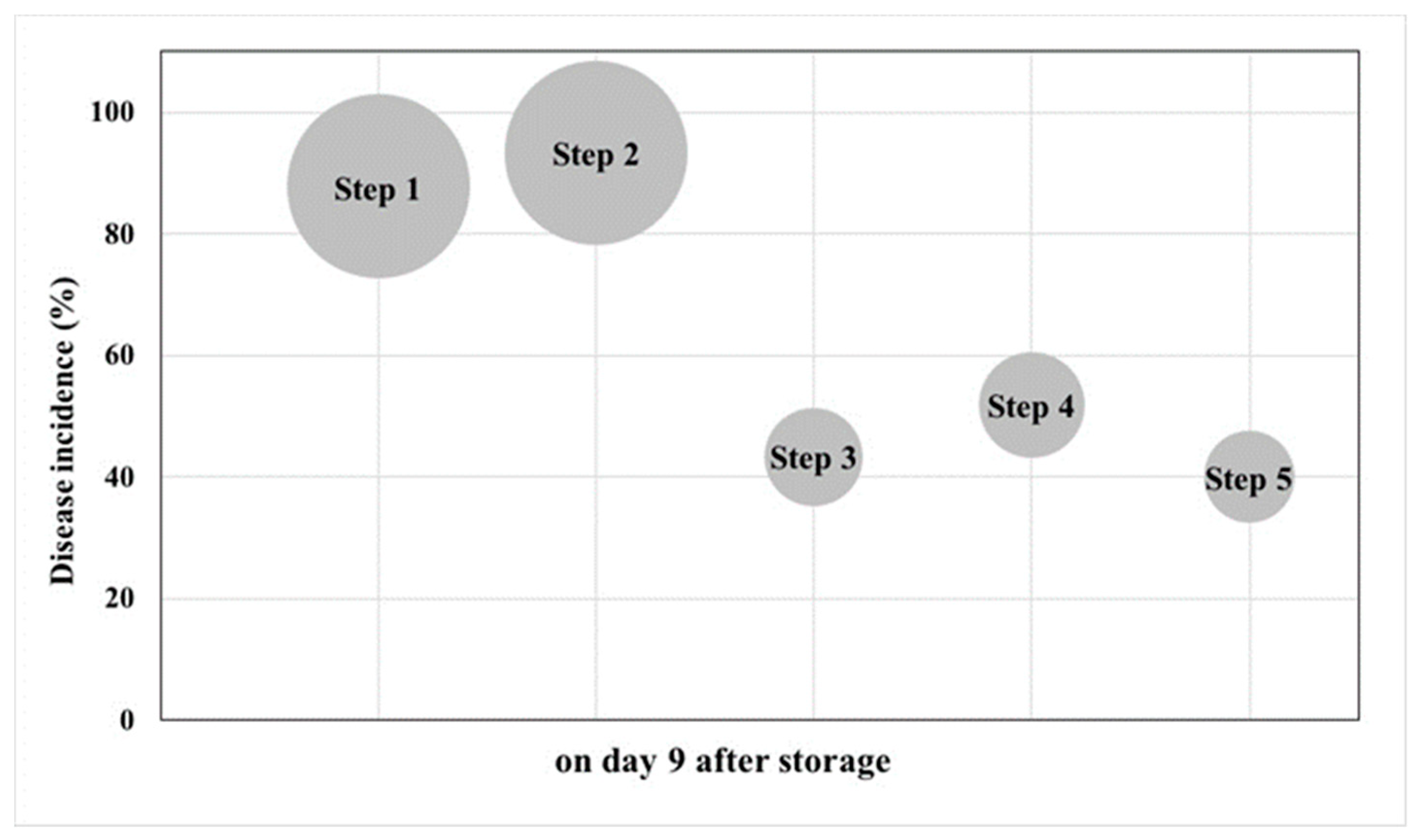

- Warehouse of exporter: Mangoes from different growers were separated using various colors of plastic containers, and paper notes with the name of the grower and received date were attached. The post-harvest handling of mango followed the method of “first in, first out” (Step 1). The process of mango handling began with cutting the pedicle and washing the fruit in a 200 mg·L−1 chlorine solution (Step 2). Mangoes were dipped in hot water at 50 °C for 3 min and left to cool down in the air (Step 3). Fruit was then dipped in 400 mg·L−1 ethephon (Step 4). After air drying, mangoes were graded and treated by vapor heat to increase the pulp temperature to 47 °C for 20 min, this was done by agricultural technical officers from both Thailand and Japan (Step 5). The treated fruit was packed with 3–5 kg per box. A sticker indicating the production date, grower code, and expiry date was put on each individual fruit. Before departure to the airport, the mangoes were randomly sampled for quality checking by agricultural technical officers from both Thailand and Japan’s Departments of Agriculture (DOA).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Office of Agricultural Economics. Thailand Foreign Agricultural Trade Statistics 2017; Office of Agricultural Economics: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Agricultural Economics. Agricultural Statistics of Thailand in 2015; Office of Agricultural Economics: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015; p. 110. [Google Scholar]

- Arauz, L.F. Mango anthracnose: Economic impact and current options for integrated management. Plant Dis. 2000, 84, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitkethley, R.; Conde, B. Mango anthracnose. North. Territ. Gov. 2007, 23, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, A.K. Anthracnose diseases of some common medicinally important fruit plants. Plant Med. Stud. 2016, 4, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, J.C.; Bugante, R.; Koomen, I.; Jeffries, P.; Jeger, M.J. Pre-and post-harvest control of mango anthracnose in the Philippines. Plant Pathol. 1991, 40, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekananthan, R.; Ravi, M.; Ramanathan, A.; Kumar, N.; Samiyappan, R. Pre-harvest application of a new biocontrol formulation induces resistance to post-harvest anthracnose and enhances fruit yield in mango. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2006, 45, 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.; Iram, S.; Rasool, A. Current status of mango pre and post-harvest diseases with respect to environmental factors. Int. J. Agron. Agric. Res. 2006, 8, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chomchalow, N.; Na Songkhla, P. Thai mango export: A slow-but-sustainable development. Assumpt. Univ. J. Technol. 2008, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Thai Agricultural Standard. Pesticide Residues: Maximum Residue Limits; TAS 9002-2008; National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives: Bangkok, Thailand, 2008; p. 44.

- Woods, E.J. Supply chain management: Understanding the concept and its implications in developing countries. In Agriproduct Supply Chain Management in Developing Countries; Johnson, G.I., Hofman, P.J., Eds.; ACIAR Proceedings: Canberra, Australia, 2004; No. 119; pp. 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Collin, R. Supply chain in new and emerging fruit industries: The management of quality as strategic tool. Acta Horticuturae 2003, 604, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolstorff, P.; Rosenbaum, R.G. Supply Chain Excellence: A Handbook for Dramatic Improvement Using the SCOR Model, 1st ed.; AMACOM, American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, P.; Aschan, M. Reference method for analyzing material flow, information flow and information loss in food supply chains. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwong, S. Postharvest Physiology and Quality Differences between ’Nam Dok Mai’ and ’Nam Dok Mai See Thong’ Mangoes during Storage. Master’s Thesis, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gaikwad, S.P.; Chalak, S.U.; Kamble, A.B. Effect of spacing on growth, yield and quality of mango. J. Krishi Vigyan 2017, 5, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.M.; Ahmad, E.; Bhagat, B.K.; Singh, D. Effect of planting space and pruning intensity in mango (Mangifera indica L.) cv. Amrapali. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa, H.; Manabe, K.; Esguerra, E.B. Bagging of fruit on the tree to control disease. Acta Horticulturae 1992, 321, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanawan, A.; Watanawan, C.; Jarunate, J. Bagging ‘Nam Dok Mai #4’ mango during development affects color and fruit quality. Acta Horticulturae 2008, 787, 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Sardsud, U.; Sardsud, V.; Singkaew, S. Postharvest loss assessment of mango cv. Nam Dok Mai. Postharvest Newsl. 2005, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Matulaprungsan, B.; Boonyaritthongchai, P.; Wongs-Aree, C.; Kanlayanarat, S.; Srisurapanon, V. Postharvest disease development in the supply chain in Thailand. Acta Horticulturae 2015, 1088, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntap, S. Postharvest Disease of Mangoes Caused by Stem End Rot Fungus (Botryodiplodia theobromae Pat.) and Its Control. Master’s Thesis, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Siripanich, J. Postharvest Physiology and Technology of Fruits and Vegetables; Kasetsart University Press: Bangkok, Thailand, 2001; 396p. [Google Scholar]

- Boonsiri, A.; Jingtair, S. How to Export Mangoes; Kasetsart University Press: Bangkok, Thailand, 2007; 37p. [Google Scholar]

- Esguerra, E.B.; Valerio-Traya, R.F.; Lizada, M.C.C. Efficacy of different heat treatment procedures in controlling diseases of mango fruits. Acta Horticulturae 2004, 645, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koslanund, R.; Khompeng, K.; Dejnumbunchachai, W. Hot water brushing: An alternative method for vapor heat treatment to reduce anthracnose disease of mango fruits. Agric. Sci. J. 2011, 42, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

| SCOR Item | Descriptor | Percentage of Growers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | ||

| 1. Sex | - Male | 75 | 75 | 76.9 |

| - Female | 25 | 25 | 23.1 | |

| 2. Age | - < 30 y | - | - | - |

| - 31–50 y | 50.1 | 81.2 | 76.9 | |

| - > 51 y | 49.9 | 18.8 | 23.1 | |

| 3. Education | - Primary school | 43.8 | 31.3 | 46.2 |

| - High school | 43.7 | 43.6 | 23 | |

| - Vocational school | 0 | 18.8 | 15.4 | |

| - Bachelor’s degree | 12.5 | 6.3 | 15.4 | |

| 4. Experience in mango growing | - < 5 y | 6.2 | 0 | 7.7 |

| - 6–10 y | 50 | 25 | 15.3 | |

| - 11–15 y | 18.8 | 43.8 | 30.8 | |

| - > 15 y | 25 | 31.2 | 46.2 | |

| 5. GAP certification | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 6. GAP experience | - < 3 y | 25 | 18.8 | 30.8 |

| - 4–8 y | 56.2 | 75 | 15.4 | |

| - > 8 y | 18.8 | 6.2 | 53.8 | |

| 7. Purchase Channel | - To collector at orchard | 0 | 0 | 6.7 |

| - To exporter at orchard | 37.5 | 43.8 | 53.8 | |

| - Transported to collecting group | 62.5 | 56.2 | 46.2 | |

| Mango Cultivar | Percentage of Plants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | |

| Nam Dok Mai No. 4 | 22.6 | 39.4 | 35.5 |

| Nam Dok Mai Sithong | 56.9 | 44.1 | 42.6 |

| Other cultivars | 20.5 | 16.5 | 21.9 |

| Location | Days after Storage | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | |

| Orchard 1 | ||||||

| Nam Dok Mai Sithong | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 40 |

| Nam Dok Mai No. 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53.3 | 86.7 |

| Orchard 2 | ||||||

| Nam Dok Mai Sithong | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 40 |

| Nam Dok Mai No. 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 100 |

| Orchard 3 | ||||||

| Nam Dok Mai Sithong | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 63.3 | 90 |

| Nam Dok Mai No. 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.3 | 26.7 | 70 |

| Orchard 4 | ||||||

| Nam Dok Mai Sithong | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Nam Dok Mai No. 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 |

| Orchard 5 | ||||||

| Nam Dok Mai Sithong | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 70 | 83.3 |

| Nam Dok Mai No. 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43.3 | 50 | 76.7 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.7 | 39.3 | 63 |

| SCOR Item | Descriptor | Percentage of Growers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | ||

| 1. Branch trimming | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 2. Trimmed branch management | - moved from the field | 0 | 12.5 | 7.7 |

| - kept in the field | 100 | 87.5 | 92.3 | |

| 3. Fallen fruit management | - moved from the field | 31.3 | 31.3 | 38.5 |

| - kept in the field | 68.7 | 68.7 | 61.5 | |

| 4. Irrigation | - practiced | 18.8 | 0 | 30.8 |

| - not practiced | 81.2 | 100 | 69.2 | |

| 5. Source of water | - ground water | 68.8 | 43.7 | 46.2 |

| - irrigation canal | 6.2 | 18.8 | 7.7 | |

| - both ground water and irrigation canal | 6.2 | 37.5 | 15.3 | |

| - not practiced | 18.8 | 0 | 30.8 | |

| 6. Fruit fly control | - chemical spray | 93.8 | 100 | 92.3 |

| - insect trap | 6.3 | 0 | 7.7 | |

| SCOR Item | Descriptor | Percentage of Growers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | ||

| 1. Frequency of pesticide application | ||||

| - every 7 days | - | - | - | |

| - every 10 days | 62.5 | 43.8 | 84.6 | |

| - every 14 days | 37.5 | 56.2 | 15.4 | |

| 2. Pesticide application before fruit bagging | ||||

| - less than 1 day | 68.8 | 68.8 | 61.5 | |

| - 1 day | 18.8 | 25 | 38.5 | |

| - 2 days | 12.4 | 6.2 | 0 | |

| 3. Recycling of bagging materials | ||||

| - Not reused | 6.3 | 6.3 | 0 | |

| - 2 times | 56.3 | 56.3 | 69.2 | |

| - 3 times | 37.4 | 37.4 | 30.8 | |

| SCOR Item | Descriptor | Percentage of Growers |

|---|---|---|

| Do you know “Trace-back System”? | -no | 97.93 |

| -yes | 2.07 | |

| Can you trace back your product to your field? | -unable | 71.97 |

| -able | 28.03 | |

| Field management recording | -always | 10.87 |

| -only when applying for the renewal of GAP | 89.13 |

| Problems | Percentage of Growers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | Average | |

| 1. Uncertainty of price | 12.5 | 31.3 | 38.5 | 26.7 |

| 2. Low quality of fruit | 12.5 | 37.5 | 15.4 | 22.2 |

| 3. No irrigation system | 25 | 43.8 | 30 | 33.3 |

| 4. Natural disasters | 100 | 81.3 | 84.6 | 88.9 |

| 5. Diseases and insects | 56.3 | 68.8 | 38.5 | 55.6 |

| 6. Labor shortage | 68.8 | 62.5 | 76.9 | 68.9 |

| 7. Chemical residue remaining | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matulaprungsan, B.; Wongs-Aree, C.; Penchaiya, P.; Boonyaritthongchai, P.; Srisurapanon, V.; Kanlayanarat, S. Analysis of Critical Control Points of Post-Harvest Diseases in the Material Flow of Nam Dok Mai Mango Exported to Japan. Agriculture 2019, 9, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9090200

Matulaprungsan B, Wongs-Aree C, Penchaiya P, Boonyaritthongchai P, Srisurapanon V, Kanlayanarat S. Analysis of Critical Control Points of Post-Harvest Diseases in the Material Flow of Nam Dok Mai Mango Exported to Japan. Agriculture. 2019; 9(9):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9090200

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatulaprungsan, Benjamaporn, Chalermchai Wongs-Aree, Pathompong Penchaiya, Panida Boonyaritthongchai, Viroat Srisurapanon, and Sirichai Kanlayanarat. 2019. "Analysis of Critical Control Points of Post-Harvest Diseases in the Material Flow of Nam Dok Mai Mango Exported to Japan" Agriculture 9, no. 9: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9090200

APA StyleMatulaprungsan, B., Wongs-Aree, C., Penchaiya, P., Boonyaritthongchai, P., Srisurapanon, V., & Kanlayanarat, S. (2019). Analysis of Critical Control Points of Post-Harvest Diseases in the Material Flow of Nam Dok Mai Mango Exported to Japan. Agriculture, 9(9), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9090200