Drivers of Farmers’ Adoption Intention for Soil Nutrient Analyzers: Roles of Awareness, Perceived Usefulness, and Ease of Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Information

1.2. Implementation of Soil Nutrient Analyzer

1.3. Background and Research Gap

1.4. Scope and Psychological Variables Selection

1.4.1. Scope of the Study

1.4.2. Psychological Variables Selection

2. Literature Review

2.1. Customer Perception Theory

2.2. Technology Adoption Model

2.3. Research Hypothesis Development

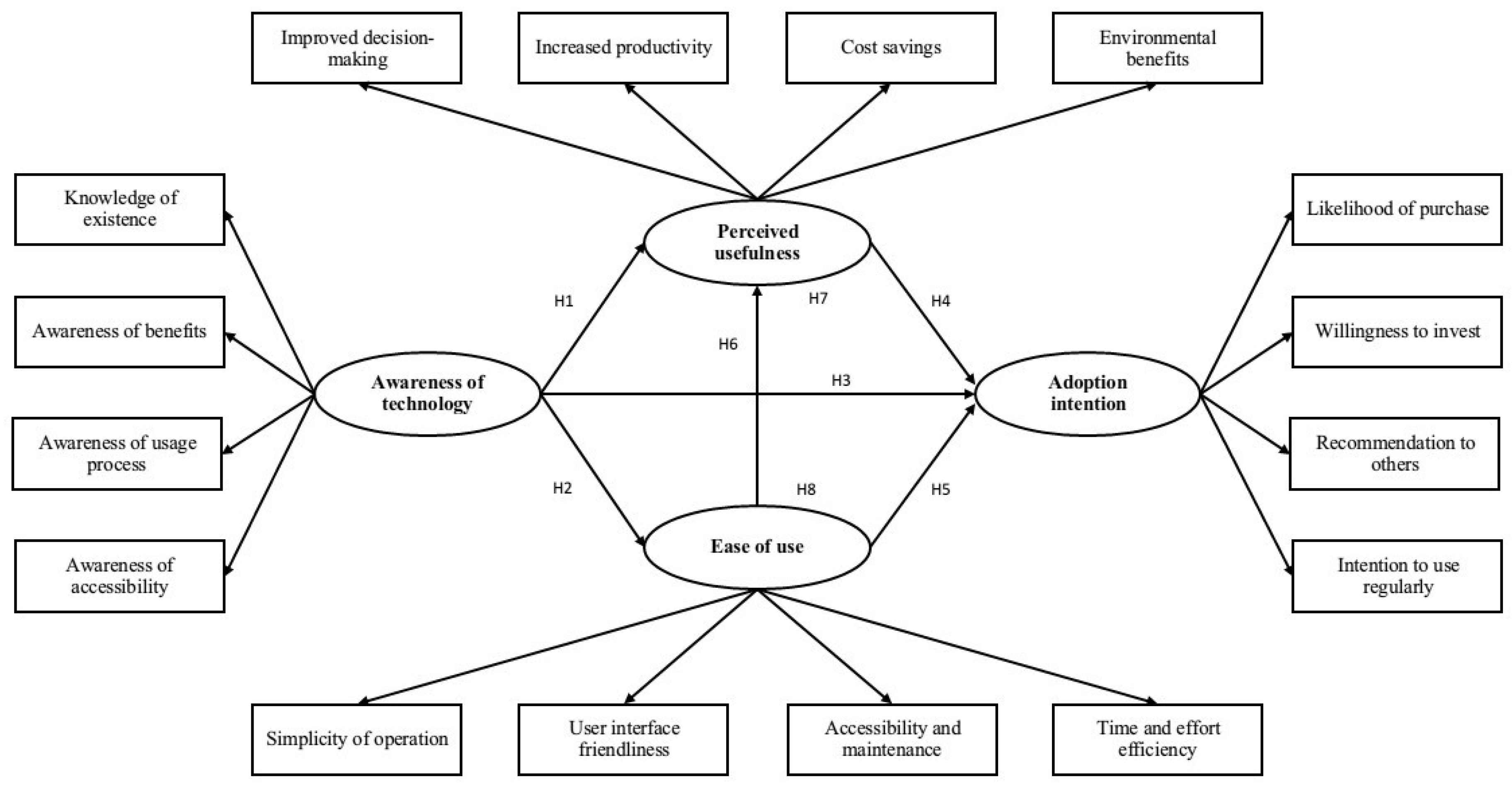

2.3.1. The Relationship Between Technology Awareness Factor and Perceived Usefulness Factor

2.3.2. The Relationship Between Technology Awareness Factor and Ease of Use Factor

2.3.3. The Relationship Between Technology Awareness Factor and Adoption Intention Factor

2.3.4. The Relationship Between Perceived Usefulness Factor and Adoption Intention Factor

2.3.5. The Relationship Between Ease of Use Factor and Adoption Intention Factor

2.3.6. The Relationship Between Ease of Use Factor and Perceived Usefulness Factor

2.3.7. The Relationship Between Awareness of Technology Factor and Adoption Intention Factor as Perceived Usefulness a Mediator Factor

2.3.8. The Relationship Between Awareness of Technology Factor and Adoption Intention Factor as Ease of Use a Mediator Factor

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Study Context

3.2. Sample Selection and Data Collection

3.3. Measurement Instruments and Variables

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information and Details of Using Soil Nutrient Analyzer

4.2. Validity and Reliability Results

Normality and Multicollinearity of the Data

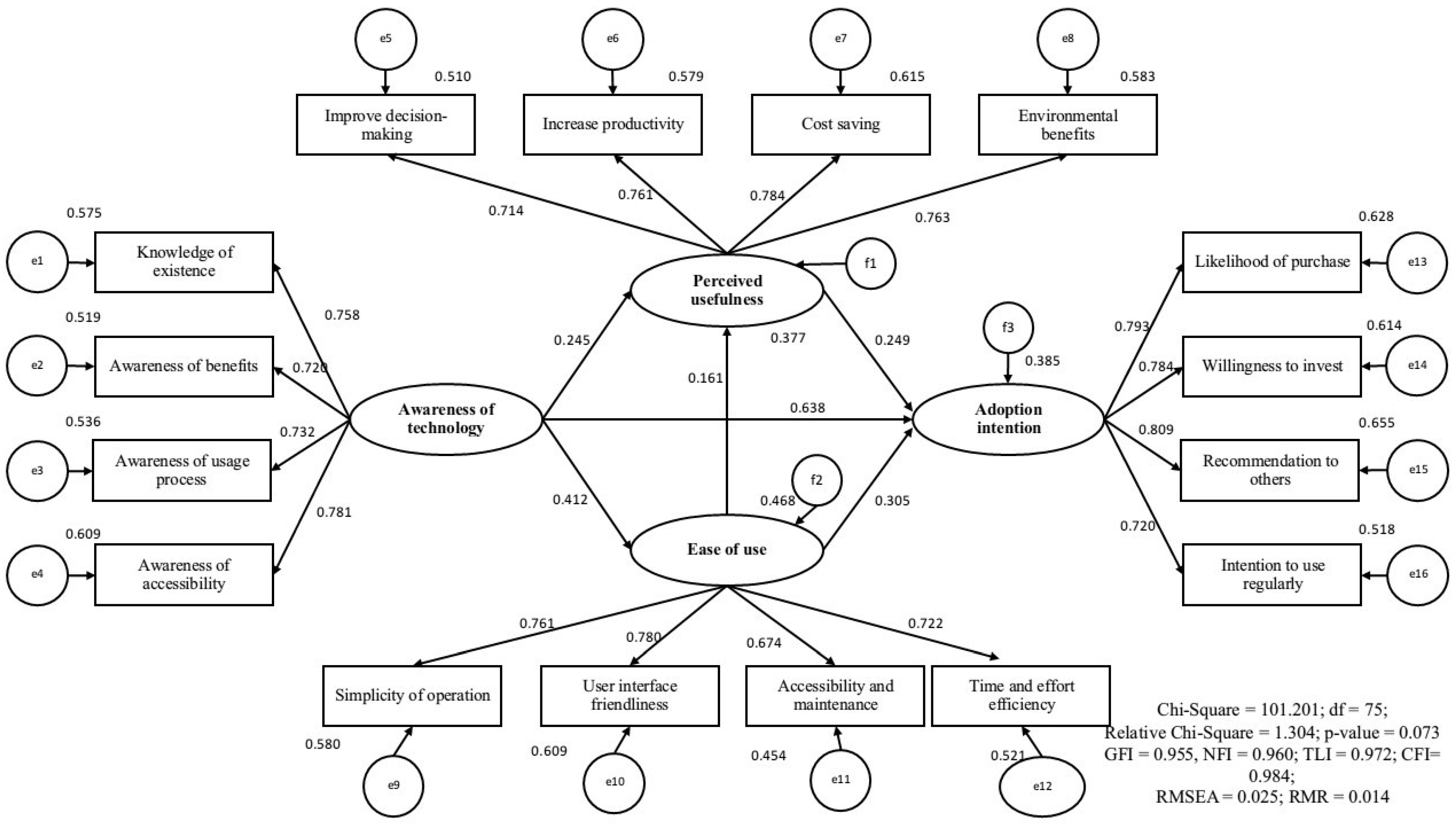

4.3. Findings Derived from the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis

4.4. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

Strength of Direct Effects in the Structural Model

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

6.2. Practical Implication

6.3. Research Limitations

6.4. Future Research Areas

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Christiaensen, L.; Martin, W. Agriculture, structural transformation and poverty reduction: Eight new insights. World Dev. 2018, 109, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, A. The Environmental Impacts of Overpopulation. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.; Nordin, S.M.; Rahman, I.; Noor, A. The effects of knowledge transfer on farmers decision making toward sustainable agriculture practices: In view of green fertilizer technology. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 15, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdoda, L.; Mdiya, L. Factors affecting the using information and communication technologies (ICTs) by livestock farmers in the Eastern Cape province. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2026017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najdenko, E.; Lorenz, F.; Dittert, K.; Olfs, H.-W. Rapid in-field soil analysis of plant-available nutrients and pH for precision agriculture—A review. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 3189–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Lyu, J.; Xue, Y. What Influences Farmers’ Adoption of Soil Testing and Formulated Fertilization Technology in Black Soil Areas? An Empirical Analysis Based on Logistic-ISM Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, M.N.; Lee, K.-H.; Karim, M.R.; Haque, M.A.; Bicamumakuba, E.; Dey, P.K.; Jang, Y.Y.; Chung, S.-O. Trends of Soil and Solution Nutrient Sensing for Open Field and Hydroponic Cultivation in Facilitated Smart Agriculture. Sensors 2025, 25, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyomi, Y. The Role of Soil Nutrient Analysis: Essential Component of Precision Agriculture. Agrotechnology 2024, 13, 394. [Google Scholar]

- Pandian, K.; Mustaffa, M.R.A.F.; Mahalingam, G.; Paramasivam, A.; John Prince, A.; Gajendiren, M.; Rafiqi Mohammad, A.R.; Varanasi, S.T. Synergistic conservation approaches for nurturing soil, food security and human health towards sustainable development goals. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, T.P.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Dougill, A.J.; Stringer, L.C. Benefits and barriers to the adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices in West Africa: A systematic review. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 2024, 3, e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Bhandari, N.; Maraseni, T.; Devkota, N.; Khanal, G.; Bhusal, B.; Basyal, D.; Paudel, U.; Danuwar, R. Technology in farming: Unleashing farmers’ behavioral intention for the adoption of agriculture 5.0. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.-S.; Cha, J.-E.; Jang, D.-H. A Study on the Acceptance of Innovative Technology by Young Farmers: Focusing on Young Farmers Who Grow Strawberries. Korean J. Agric. Manag. Policy 2022, 49, 212–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffaro, F.; Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Roccato, M.; Cavallo, E. Drivers of farmers’ intention to adopt technological innovations in Italy: The role of information sources, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.; Liu, L.; Zhao, J.; Kang, X.; Wang, W. Digital Technologies Adoption and Economic Benefits in Agriculture: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Al Mamun, A.; Masukujjaman, M.; Masud, M.M. Acceptance of new agricultural technology among small rural farmers. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z. Farmers’ adoption of smart agricultural technologies for black soil conservation and utilization in China: The driving factors and its mechanism. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1561633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, K.; Aashish, K.; Kumar Dwivedi, A. Antecedents of smart farming adoption to mitigate the digital divide—Extended innovation diffusion model. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, S.; Jamshidi, O.; Fozouni, Z. Cultivating knowledge: The adoption experience of learning management systems in agricultural higher education. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1551546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathiraja, M.A.; Wijesinghe, W.A.S.; Kumara, A.P. Smart Agro Soil Analyzer for Sustainable Farming. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Image Processing and Robotics (ICIPRoB), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 9–10 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tobiszewski, M.; Vakh, C. Analytical applications of smartphones for agricultural soil analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 3703–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigus, G.; Ketema, M.; Haji, J.; Sileshi, M. Determinants of adoption of urban agricultural practices in eastern Haraghe zone of Oromia region and Dire Dawa City administration, eastern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Liang, F.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, J. Factors influencing farmers’ adoption of eco-friendly fertilization technology in grain production: An integrated spatial–econometric analysis in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Peng, Q. Bridging the Digital Divide: Unraveling the Determinants of FinTech Adoption in Rural Communities. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241227770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, R. Study on the influence mechanism of adoption of smart agriculture technology behavior. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, M.; Keske, C. From profitability to trust: Factors shaping digital agriculture adoption. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1456991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Tian, M.; Nian, Y.; Ren, W.; Ma, H.; Liang, F. Farmers’ adoption of green prevention and control technology in China: Does information awareness matter? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzante, S.; Labarta, R.; Bilton, A. Adoption of agricultural technology in the developing world: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigezu, Y.A.; Mugera, A.; El-Shater, T.; Aw-Hassan, A.; Piggin, C.; Haddad, A.; Khalil, Y.; Loss, S. Enhancing adoption of agricultural technologies requiring high initial investment among smallholders. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 134, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wang, H.; Han, J. Understanding Ecological Agricultural Technology Adoption in China Using an Integrated Technology Acceptance Model—Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 927668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Cheng, K. What Drives the Adoption of Agricultural Green Production Technologies? An Extension of TAM in Agriculture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, P.B.; Pham, T.T.L.; Quynh, N.N.; Doanh, N.K. Farmers’ adoption and effects of three aspects of agricultural information systems in emerging economies: Microanalysis of household surveys. Inf. Dev. 2024, 02666669241247769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Pourdarbani, R.; Asgarnezhad Nouri, B. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Agricultural Automation Using Davis’s Acceptance Model (Case Study: Ardabil). Acta Technol. Agric. 2020, 23, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyasit, K.; Singhavara, M.; Srihirun, J.; Wangsathian, S.; Nonthapot, S. A study to assess the readiness of rice farmers to use agricultural technology for production in Nong Khai Province, Thailand. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Stud. 2024, 7, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, B. The influence of technology perceptions on farmers’ water-saving irrigation technology adoption behavior in the North China Plain. Water Policy 2024, 26, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, P.; Chen, K.; Wu, L. Factors affecting the willingness of agricultural green production from the perspective of farmers’ perceptions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J.; Wu, L.; Yin, S. Adoption behavior of green control techniques by family farms in China: Evidence from 676 family farms in Huang-huai-hai Plain. Crop Prot. 2017, 99, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbri, I.A.; Alias, M.R.M.; Fauzan, A.F.; Ismail, M.F.; Widjajanti, K.; Kurnianingrum, D.; Karmagatri, M. Awareness and Acceptance of the Internet of Things (IOT) among Agropreneurs. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 1712–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Liang, J.; Nian, Y.; Ma, H. Impact of Environmental Values and Information Awareness on the Adoption of Soil Testing and Formula Fertilization Technology by Farmers—A Case Study Considering Social Networks. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of Business Research Methods, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, UK, 2019; p. 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, UK, 1988; p. 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, A.; Guo, L.; Li, H. Understanding farmer cooperatives’ intention to adopt digital technology: Mediating effect of perceived ease of use and moderating effects of internet usage and training. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2025, 23, 2464523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontsa, N.V.; Mushunje, A.; Ngarava, S. Factors Influencing the Perceptions of Smallholder Farmers towards Adoption of Digital Technologies in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okai, G.; Agangiba, W.; Agangiba, M. Assessment of Farmers’ Acceptance of Intelligent Agriculture System Using Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2024, 186, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontsa, N.V.; Mushunje, A.; Ngarava, S.; Zhou, L. Awareness and Perception of Digital Technologies by Smallholder Farmers in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Agric. Ext. 2024, 52, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piot-Lepetit, I. Editorial: Strategies of digitalization and sustainability in agrifood value chains. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1565662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, E.D.; Sasaki, N.; Tsusaka, T.W.; Silpasuwanchai, C. Investigating farmers’ adoption of mobile Agri-Tech: A TAM-Based study of KaseChar in Eastern Thailand. Glob. Transit. 2025, 7, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidyan Far, S.; Rezaei-Moghaddam, K.; Shokri koochak, S. An integrated model for analyzing farmers’ behavioral intention towards the acceptance of environmental technologies. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, A.A.; Asadi, A.; Sardar Shahraki, H.; Dehghani Pour, M.; Naroui Rad, M.R. Farmers’ attitude and intention towards medicinal plants cultivation: Experiences from semi-arid areas of Iran. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 231, 105465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liow, G.; Yuan, S. E-commerce adoption among micro agri-business enterprise in Longsheng, China: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 972543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, Y.; Azmey, M.; Syed Ibrahim, S. E-Commerce Adoption Among Malaysian SMEs: Key Drivers and Business Performance Implications. IJRISS 2025, IX, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamondetdacha, R. Adoption of Mobile Applications in Agriculture among Farmers in Nan, Thailand. J. Digit. Commun. 2022, 6, 69–96. Available online: https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/NBTC_Journal/article/view/260371 (accessed on 4 February 2026).

- Wang, Y.-n.; Jin, L.; Mao, H. Farmer Cooperatives’ Intention to Adopt Agricultural Information Technology—Mediating Effects of Attitude. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L. Intelligent Hog Farming Adoption Choices Using the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Model: Perspectives from China’s New Agricultural Managers. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhang, S.; Wang, T.; Hu, J.; Ruan, J.; Ruan, J. Willingness and Influencing Factors of Pig Farmers to Adopt Internet of Things Technology in Food Traceability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengavut, V.; Jirasatthumb, N. Smallholder decision-making process in technology adoption intention: Implications for Dipterocarpus alatus in Northeastern Thailand. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Description (Farmer Perception Perspective) |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Technology Awareness → Perceived Usefulness | Higher awareness of soil nutrient analyzers enhances farmers’ perceptions of their usefulness in improving productivity and decision-making. |

| H2 | Technology Awareness → Ease of Use | Greater awareness leads farmers to perceive soil nutrient analyzers as easier to operate and understand. |

| H3 | Technology Awareness → Adoption Intention | Farmers with higher awareness show stronger intention to adopt soil nutrient analyzers. |

| H4 | Perceived Usefulness → Adoption Intention | When farmers perceive the technology as beneficial, their intention to adopt it increases. |

| H5 | Ease of Use → Adoption Intention | Technologies perceived as simple and user-friendly positively influence farmers’ adoption intention. |

| H6 | Ease of Use → Perceived Usefulness | Greater perceived ease of use enhances farmers’ perceptions of the technology’s usefulness. |

| H7 | Technology Awareness → Perceived Usefulness → Adoption Intention | Perceived usefulness mediates the relationship between technology awareness and adoption intention. |

| H8 | Technology Awareness → Ease of Use → Adoption Intention | Ease of use mediates the relationship between technology awareness and adoption intention. |

| Items | Details | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 168 | 43.1 |

| Female | 222 | 56.9 | |

| Age | 20–29 years | 30 | 7.7 |

| 30–39 years | 35 | 9.0 | |

| 40–49 years | 288 | 73.8 | |

| More than 49 years | 37 | 9.5 | |

| Monthly income (USD) | Less than 343 | 50 | 12.8 |

| 344–572 | 49 | 12.5 | |

| 573–800 | 242 | 62.0 | |

| More than 800 | 49 | 12.7 | |

| Planted crop | Durian | 124 | 31.8 |

| Orange | 133 | 34.1 | |

| Rice | 133 | 34.1 | |

| Sources of information about soil analyzer | Family | 70 | 17.9 |

| Friend | 160 | 41.1 | |

| Internet | 80 | 20.5 | |

| Others | 80 | 20.5 | |

| 1 Time | 216 | 55.3 | |

| Number of Using experience | 2 Times | 92 | 23.5 |

| More than 2 times | 82 | 21.2 |

| Construct | Variables | Factor Loading | CR | AVE | R2 | MSV | ASV | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of technology | Knowledge of existence | 0.630 | 0.836 | 0.560 | 0.565 | 0.433 | 0.321 | 0.826 |

| Awareness of benefits | 0.675 | 0.520 | ||||||

| Awareness of usage process | 0.676 | 0.544 | ||||||

| Awareness of accessibility | 0.651 | 0.612 | ||||||

| Perceived usefulness | Improve decision-making | 0.681 | 0.824 | 0.541 | 0.575 | 0.843 | ||

| Increased productivity | 0.678 | 0.607 | ||||||

| Cost saving | 0.670 | 0.542 | ||||||

| Environmental benefits | 0.691 | 0.522 | ||||||

| Ease of use | Simplicity of operation | 0.633 | 0.842 | 0.572 | 0.511 | 0.842 | ||

| User interface friendliness | 0.705 | 0.573 | ||||||

| Accessibility and maintenance | 0.706 | 0.517 | ||||||

| Time and effort efficiency | 0.672 | 0.577 | ||||||

| Adoption intention | Likelihood of purchase | 0.739 | 0.843 | 0.604 | 0.682 | 0.843 | ||

| Willingness to invest | 0.653 | 0.615 | ||||||

| Recommendation to others | 0.687 | 0.543 | ||||||

| Intention to use regularly | 0.670 | 0.612 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Path Coefficient | p-Value | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | AT → PU | 0.245 ** | 0.007 | Supported |

| H2 | AT → EU | 0.412 *** | <0.001 | Supported |

| H3 | AT → AI | 0.638 ** | 0.006 | Supported |

| H4 | PU → AI | 0.249 *** | <0.001 | Supported |

| H5 | EU → AI | 0.305 ** | 0.007 | Supported |

| H6 | EU → PU | 0.161 * | 0.005 | Supported |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | p-Value | Mediation | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H7 | AT → AI | 0.347 *** | 0.006 | Partial | Supported | |

| AT → PU → AI | 0.042 * | 0.035 | Supported | |||

| H8 | AT → AI | 0.307 ** | 0.003 | Partial | Supported | |

| AT → EU → AI | 0.071 * | 0.041 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Suvittawat, A. Drivers of Farmers’ Adoption Intention for Soil Nutrient Analyzers: Roles of Awareness, Perceived Usefulness, and Ease of Use. Agriculture 2026, 16, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030390

Suvittawat A. Drivers of Farmers’ Adoption Intention for Soil Nutrient Analyzers: Roles of Awareness, Perceived Usefulness, and Ease of Use. Agriculture. 2026; 16(3):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030390

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuvittawat, Adisak. 2026. "Drivers of Farmers’ Adoption Intention for Soil Nutrient Analyzers: Roles of Awareness, Perceived Usefulness, and Ease of Use" Agriculture 16, no. 3: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030390

APA StyleSuvittawat, A. (2026). Drivers of Farmers’ Adoption Intention for Soil Nutrient Analyzers: Roles of Awareness, Perceived Usefulness, and Ease of Use. Agriculture, 16(3), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030390