1. Introduction

Today, agriculture faces several challenges due to climate change, including soil degradation, the scarcity of natural resources, and an increasing population demand for fresh food at any time [

1]. Therefore, the rise of sustainable technological strategies, such as Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA), becomes significant in increasing the efficiency of food production with an effective use of key resources such as water and nutrients. As an example of these technologies, it is possible to cite vertical agriculture and advanced hydroponic cultivation [

2].

Hydroponics has been established as a key technique from CEA as a result of its efficient use of water, nutrients, and available space for cultivating. It has been proven that hydroponic systems not only reduce water consumption by around 90% in comparison to conventional agriculture but also significantly increase crop density by using vertical configurations, for example [

3].

With the use of hydroponic systems with controlled environments, several studies have demonstrated the efficiency of hydroponic systems in vegetables cultivation, as in the case of lettuce and spinach. In these studies, the efficient use of resources resulted in a significant yield. Additionally, the cultivated vegetables showed a better content of sugars, vitamin C, and minerals, and a low nitrate accumulation [

1,

4,

5]. Consequently, these types of systems have been extended to include hybrid configurations of vertical hydroponics and aeroponics to cultivate tubers such as radishes and turnips [

6]. Recent studies have shown that hydroponic systems have a good performance for cultivating Swiss chard (

Beta vulgaris var. cicla), where crops achieve excellent sizes and a rich nutritional content. Then, evaluating the impact of controlled environmental variables (e.g., controlled lighting systems) in Swiss chard growing and its nutritional quality becomes relevant in identifying the key factors that could aid in the production of crops with the highest quality [

7,

8].

Recently, the use of light spectrum treatments has been reported as a key factor in both the morphological and nutritional characteristics of vegetables, i.e., the light spectrum influences biomass, foliar area, growth, and the content of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. As an example, it is noteworthy that the use of a 1:1 red–blue light system with a lighting condition ranging between 100–200 µmol m

−2·s

−1 improves the yield and the mineral content in lettuce. Additionally, ref. [

9] has reported that the red–blue light spectra increase biomass; moreover, it was found that using green, purple, and far-red spectra modifies the physiological and nutritional parameters in the plant, resulting in a vitamin C increment. Similarly, ref. [

10] has concluded that mixing blue (450 nm), red (663 nm), and green (520 nm) light with a 1.25 ± 0.1 B435/R663 proportion with a low intensity of 60 µmol m

−2·s

−1 promotes higher yields and more antioxidative activity.

After these findings, the present study was designed to compare two different lighting treatments for cultivating green-leaf crops in a chamber with controlled environmental variables. Here, the use of full-spectrum LED systems was set to provide a constant Photosynthetic Photon Flux (PPF) at the canopy level. With these settings, the impact of different light spectra in both the morphological characteristics and nutritional quality of the crops was analyzed. Some studies have demonstrated that LED lighting systems with different light spectra arrays, including the use of white-light spectrum, can have an influence on green-leaf crops’ growth and yield [

11].

Usually, Swiss chard (

Beta vulgaris var. cicla) can be found in markets regularly throughout the year as it is widely consumed due to its valuable nutritional content, being beneficial for health as a result of its high content of antioxidants present in the form of dietetic fiber and Omega 3 [

12,

13]. Some studies have researched the effects of cultivating chards in hydroponics systems: ref. [

14] explored the effect of the nutrient solution flow in both the chards’ growth and nutritional quality; ref. [

7] incorporated selenium as part of the nutritional treatments to see its effect on the concentration of antioxidants and pigments; and, finally, ref. [

8] compared the yield and nitrate accumulation between a hydroponic and an aquaponic system. However, neither of these studies demonstrate the effect of using different LED lighting systems in chard cultivation, where the morphological characteristics and the nutritional quality of the chard could reflect a difference. Consequently, the present study explores this topic by evaluating different LED-based lighting systems and their impact in the morphology and nutritional quality of Swiss chard, as an efficient use of resources is implemented during the cultivation. Therefore, this work contributes to our knowledge by presenting the cultivation of Swiss chard with Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) hydroponic systems using artificial lighting, as has been studied in similar vegetables such as lettuce and spinach [

15].

The use of LED technology in both hydroponic systems and controlled environment chambers has become a key factor for stimulating vegetative growth and an efficient use of resources. Particularly, the use of LED lighting systems allows us to control both the spectral composition of light and light intensity; therefore, it is possible to have an influence on the plants’ physiology and in the productivity. For example, ref. [

10] demonstrates how specific light spectra improved the plants’ growth and the biomass accumulation for a vertical agriculture system.

In CEA systems, where natural light is non-existent, artificial lighting systems using LED technology becomes a key factor for stimulating plant growth by emitting an adequate light spectrum with the correct intensity, favoring photosynthesis [

1,

6]. In general, the blue, red, and green spectra stimulate photosynthesis, resulting in absorption by the chlorophyll pigments [

16]. Conversely, some studies using vertical hydroponic systems for cultivating lettuce (

Lactuca sativa L.) emphasize that the interaction between the red–white light spectra (RW), emitted with an intensity of 180 µmol m

−2·s

−1, not only benefits its growth but also its content on antioxidants [

17]. Also, the light spectrum can be selected based on the crop stage, for example, ref. [

18] proposes the use of red and blue spectra with an intensity of 200 µmol m

−2·s

−1 during the vegetative stage to improve the growth and to increment biomass. In fact, the lighting intensity and the light spectra have been found to impact not only on the growth and development of the plants, but also on their nutritional quality [

2,

4,

5].

The nutritional parameters evaluated in this study include carbohydrates, dietary fiber, proteins, water content, and both macro- and micronutrients. These parameters were selected based on their relevance for human health and their response to the influence of controlled environmental variables and artificial lighting systems for soilless cultivation systems. Previous studies [

2,

19] stand out the influence on the quality and biochemical characteristics of green-leaf crops by artificial lighting systems, where these studies used LED lighting systems with different light spectra regulating the vegetative growth, the metabolic profiles, and the nutritional content of the crops.

It has been demonstrated that the management of the canopy while cultivating green-leaf crops with controlled environments influences growth and foliar development. Some studies point out that pruning modifies the light absorption and the development of the cultivation [

20,

21]. Despite the fact that Swiss chard cultivation might include pruning periods, this work did not consider pruning during the cultivation cycle as the evaluation of LED lighting treatments during the chard’s natural growth cycle was the main purpose of the study.

Similarly to other studies reporting the results for green-leaf crops, to compare the nutritional quality of the harvested Swiss chards in this study, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s [

22] recommendations for Swiss chard were taken as a reference. Therefore, the results presented in this study can be compared with a recognized nutritional framework for easier interpretation.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study employs a green-wall hydroponic system using an NFT configuration. The system has three hydroponic horizontal layers installed along the inner walls of a growth chamber with two purposes: to maximize the available space to cultivate crops and to guarantee uniform lighting for the crops. Like other studies, this system arises as an alternative for CEA for sustainable production of green-leaf vegetables.

2.1. Growth Chamber

This study was developed with the growth chamber shown in

Figure 1. The experiment was conducted from 3 March to 5 April 2025. This chamber with dimensions of 3 m × 3 m × 2.3 m possesses environmental control including lighting, temperature, relative humidity, and CO

2 concentration. To guarantee the environmental conditions inside the chamber, the ceiling and walls were filled with polyurethane foam to cover a 7.62 cm thickness. In addition, the chamber was conditioned with a Mirage X32 mini split air conditioning system and two humidifiers VEVOR providing 560 mL/h; CO

2 concentration was manually controlled with mechanical ventilation and based on human activity inside the chamber. During the experiment, the environment inside the chamber was set to have an 18–20 °C room temperature with a relative humidity of 60 to 70%, a CO

2 concentration between 400 and 600 ppm, and a photosynthetic active radiation between 230 and 250 µmol·m

−2·s

−1.

The growth chamber has been equipped with a set of IoT monitoring modules to record the nutrient solution quality and the environmental variables of the chamber. In the first case, a water quality IoT monitoring module (Yoidesu YD-1000) was set for recording water temperature (i.e., nutrient solution temperature), pH level, electrical conductivity (EC), and the parts per million (ppm) of the nutrient solution. In the second case, the environmental variables being monitored were the room temperature, relative humidity, carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration, and photosynthetic photon flux (PPF). The recorded measurements of these variables were uploaded to the cloud every 5 min; these records had three purposes: to have a real-time monitoring framework, to record the environmental variables during the growth cycle for their analysis, and to supply the users with historical data of different cultivations. Additionally, a D56W video surveillance (equipped with camera and microphone) system was implemented for hearing and visual monitoring of the cultivation, as well as verifying the optimal functionality of the pumping system. To access real-time audio and video, the V380Pro® para iOS, version 2.2.31 application was used.

2.2. Green-Wall Hydroponic System

In

Figure 2, the hydroponic system of this study is presented. The system implements a Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) and is built with a three-layer horizontal framework, where each layer had two parallel grow channels. All the channels have a 2% tilt which helps not only to guarantee a continuous laminar flow of the nutrient solution, to secure both an adequate oxygenation of the radicular system and an optimal contact time between the root and the nutrient solution, but also to prevent radicular hypoxia and pathogenesis [

17]. The grow channels are made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and have a 2 in diameter with a length of 280 cm. With the purpose of allocating a plastic basket for crop placement, each channel had 14 holes with a 5 cm diameter and an 18.5 cm gap. As can be seen in contour A in

Figure 2, the three layers on the left side of the picture have the same lighting system in parallel to each grow channel, which corresponds to a full spectrum 4-foot 42 W Barina LED bar (model INWT80421265Ec, Zhongshan, Guangdong, China) with predominant red and blue light spectra. On the other hand, contour B in

Figure 2 shows a set of 70 W LED panel lighting systems (model Grow Light MUFURN, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) of adjustable full spectrum with a white, red, blue, and infrared/ultraviolet (IR/UV) light spectra mixture. In this case, each layer had 3 LED panels lighting both grow channels.

The irrigation system is a closed loop that begins at the 42 L nutrient solution tank (showed at bottom right in

Figure 2) from which the solution is pumped through a 10 mm hose to each channel with a hydraulic diaphragm pump. Then, the remanent nutrient solution flowing through the channels returns to the tank due to gravity force. The horizontal and modular layout of the system allows a high-density cultivation in limited spaces and better control of the microclimate around the plants [

23]. Thus, this layout was fundamental for evaluating the effects of different lighting conditions in the morphology and nutritional quality of plants.

The modular layout was installed in the interior walls of the growth chamber, allowing an efficient use of space for cultivation, a strategic placing for the lighting systems, and an adequate irrigation management of the nutrient solution. As a result of this modular characteristic of the proposed system, and considering its development for research purposes, it is possible to compare different variables during cultivation (e.g., characteristics of a specific nutrient solution, lighting conditions, and plant spacing) under the same controlled environment. Additionally, the layout allows a high-density cultivation in controlled environments, which becomes of great interest in green-leaf vegetables cultivation.

2.3. Experimental Treatments

This work evaluates the impact of two different full-spectrum LED lighting systems in the morphology and nutritional quality of chard crops. As mentioned before, the selected lamps for the growth chamber were Barina LED bar (model INWT80421265Ec) and LED panel lighting systems (model Grow Light MUFURN); these lighting systems were of interest for this work as they have a photosynthetic active range between 400 and 700 nm. The characteristics of each treatment are explained below:

Treatment 1 (T1): This treatment was applied with a set of 12 Barina LED bars, where a bar pair was parallel to one grow channel, as can be seen in the dashed rectangle A in

Figure 2. The bars were installed with a fixed pulley system to adjust the distance between the plant and the LED bar as the crop grows during the cultivation. A 230–250 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 PPF setpoint at the foliar system was established to adjust the LED bars’ height. Based on the manufacturer information, these LED bars have predominant peaks on the blue-light spectrum at 460 nm, and on the red-light spectrum at 650 nm with secondary emissions between 640 and 660 nm. It is important to note that these spectral bands are coincident with the absorption bands of chlorophyll a and b. The LED bars also emit a far-red-light spectrum at 730 nm, whose presence is important during the growth cycle for promoting vegetative development.

Treatment 2 (T2): This treatment was applied using a set of LED panel lighting systems with full-spectrum lighting for crops in vegetative stage. Here, 21 lamps were installed evenly in the three horizontal layouts, i.e., each level had 7 lamps above the grow channels (the dashed rectangle B in

Figure 2 illustrates this arrangement). Similarly to T1, a 230–250 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 PPF setpoint at the foliar system was established to adjust the panels’ height with the aid of a fixed pulley system. Based on the manufacturer information, these LED panels have predominant peaks on UV-A-light spectrum at 395 nm, blue-light spectrum at 465 nm, red-light spectrum at 620 nm, and far-red-light spectrum at 730 nm. In addition, the panels include white-light LEDs of 3000 K and 5000 K to provide all the light spectra that compose the visible spectrum.

2.4. Proposed Crop for Study

Swiss chard (

Beta vulgaris var. cicla) was selected for this study due to the duration of its short cultivation cycle and high nutritional content [

24]. Based on similar studies as in the case of [

7], chard seedlings, with three to four true leaves, were transplanted to the growth chamber 25 days after germination (DAG); each seedling was transplanted into a hydroponic basket, then placed in an available space of a grow channel. It is important to mention that these seedlings were previously germinated in a germination house for 25 days and irrigated with micro-sprinklers. The adequate number of days after germination for transplanting the crops and the duration of the experimental cultivation cycle were established based on the technical guides for cultivating Swiss chard with hydroponic systems and with the aid of farmers with expertise in this area.

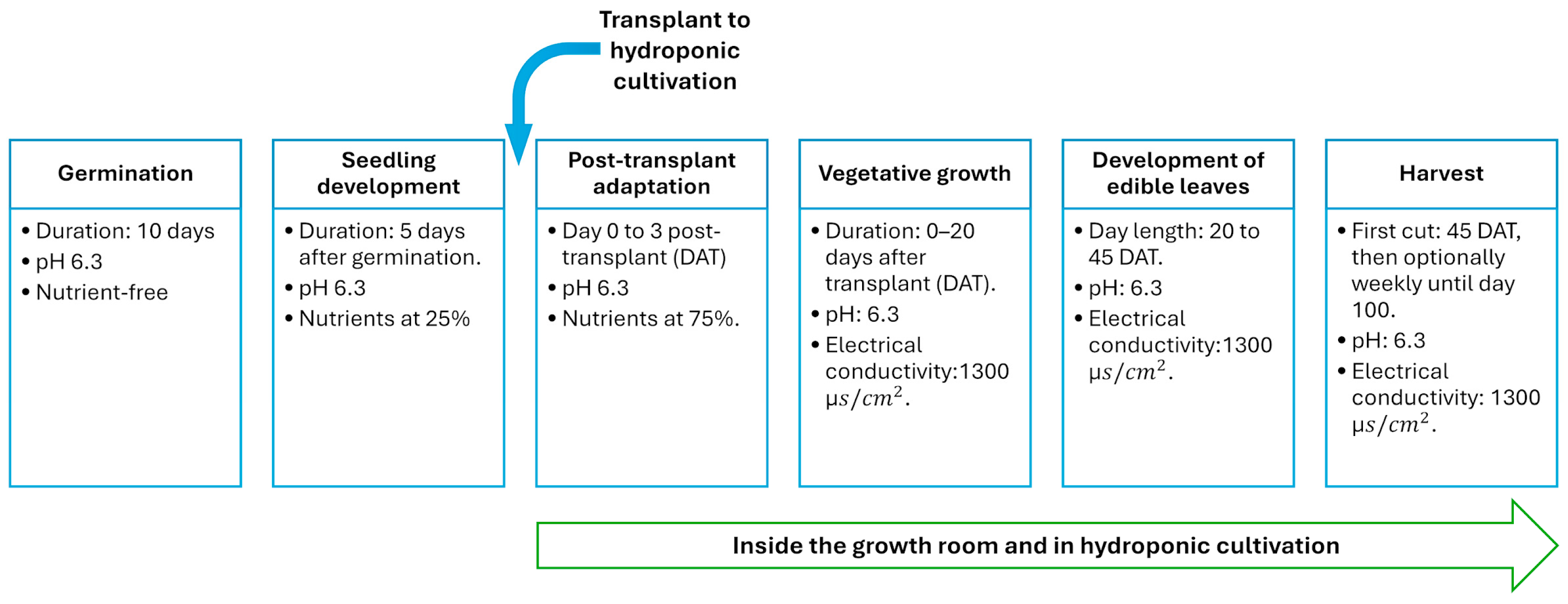

After the transplantation, the Swiss chard crops remained in cultivation for 31 more days inside the growth chamber with a controlled environment to accomplish a 56-day cultivation cycle since germination. During this period in the growth chamber, four phenological stages were defined (see

Figure 3): (1) post-transplanting adaptation, (2) vegetative growth, (3) leaves sprouting and growing, and (4) harvesting. Based on RIKOLTO, 2021 [

25], chard crops require a temperature between 18 and 20 °C with a relative humidity in the range of 60–70%, and a CO

2 concentration between 400 and 600 ppm to promote the growth of edible leaves. Additionally, the environmental control of the chamber imitated a photoperiod cycle of 14 h daylight and 10 h night with the purpose of allowing the plants to fulfill their photosynthetic and breathing cycles. These environmental conditions are resumed in

Table 1. On day 31 after the transplanting, the chard leaves were ready to be harvested.

A Steiner nutrient solution was used in this study, which was prepared based on the standardized condition of macro- and micronutrients for hydroponic cultivations with a 100% concentration. For this nutrient solution, the pH was adjusted to 6.3 ± 0.2 and electrical conductivity (EC) to 1.3 ± 0.05 mS·m

−1, values that are ideal for the absorption of nutrients by the Swiss chard (

Beta vulgaris var. cicla) and that promote its growth [

26]. It is important to mention that the preparation of the Steiner solution never considered the addition of any other agrochemical compound. During the cultivation cycle, the solution was irrigated with a constant flow of 1.8 L·s

−1, whose volume was adjusted every 5 days. The pH and EC values of the solution were regulated in a daily basis.

2.5. Performance and Efficiency Indicators

The cultivation density (D), volumetric density (Dm3), light use efficiency (LUE), and energy efficiency (EE, kg·kWh−1), as well as the water, nutrient solution, and acid consumption, were used to quantify the yield and the efficiency of the hydroponic system.

On a weekly basis, the volume of water and acid used to prepare nutrient solution was registered. In the same way, both the total volume of the prepared nutrient solution and the volume consumed by each lighting treatment was registered (liters per treatment), these values were used to calculate the solution consumption per plant. All the volume measurements were made manually and using calibrated recipients.

The cultivation density was calculated using Equation (1), where n represents the total number of cultivated plants and A is the area of the hydroponic system in m2. The density is determined as the number of cultivated plants per square meter.

Similarly, the volumetric density of the green-wall hydroponic system was calculated using the Equation (2), where n, again, represents the total number of cultivated plants, but V is the volume of the chamber in cubic meters. Therefore, the volume density represents the number of cultivated plants per cubic meter.

The LUE parameter was calculated as the relation between the accumulated dry biomass per square meter, and the active radiation received by each lighting treatment. Consequently, the LUE is measured in g·mol−1. In the case of the EE parameter, it was calculated as the relation between the fresh biomass per electric energy unit consumed (kg·kWh−1).

These indicators were a key factor in the comparison of yield, cultivation density, and the efficiency of the system against similar studies reporting hydroponic cultivations using controlled environments [

24,

25,

27,

28].

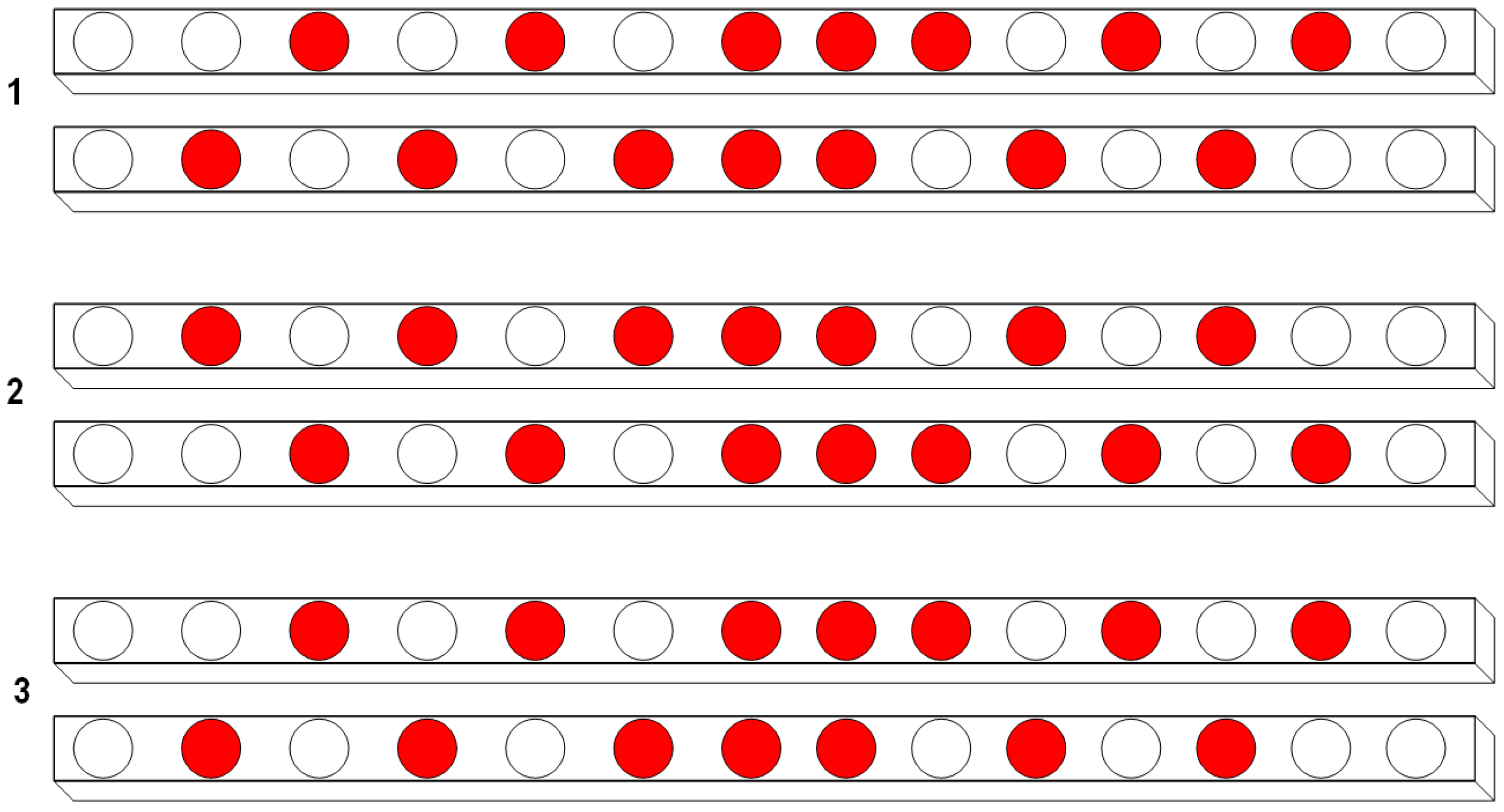

2.6. Experimental Design

A randomized experimental design was proposed for this study, considering 144 plants equally distributed in two different treatments (T1 and T2); i.e., each treatment had 72 repetitions. Based on the variance of the first measurements (calculated in transplanting day) and considering a combined sampling with a 95% confidence interval, it was found that a representative sample size for the study is

n = 42 per treatment. In

Figure 4, the spatial distribution of the selected plants (red circles) is shown for each horizontal layer of the hydroponic system. Here, the layer labeled as number 1 corresponds to the bottom layer, meanwhile the layer labeled as number 3 corresponds to the topmost layer in the hydroponic system.

During the cultivation cycle, both the physiological characteristics and growth were monitored on a 3-day basis. Particularly, these measurements were made as follows: the plants’ height was measured using a millimetric ruler, the number of leaves were counted by visual inspection, the foliar area was computed with the aid of an image processing application developed in MATLAB, (version R2022a, MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) the fresh weight was measured with a precision digital scale, and the chlorophyll was measured based on a non-destructive technique with a chlorophyll concentration meter Apogee MC-100 (Apogee Instruments, Logan, UT, USA).

At the end of the cultivation cycle (31 days after transplanting), all the Swiss chards were harvested and measured as explained in the previous paragraph. As additional information, in this stage of the experiment, the dry mass and nutritional content of the chards were obtained. In the first case, the dry mass was weighed after the chards were placed in a drying oven (model FE-131AD) set at a temperature of 72 °C for 48 h [

29]. To measure the nutritional content of the chards, three chards per treatment were randomly selected to quantify their content of macro- and micronutrients with analytical chemistry techniques commonly used for vegetable tissue [

30]. Particularly, the selected analysis for this study includes a proximal and mineral content analysis to evaluate the nutritional content of the chards. The humidity was extracted using a drying oven to perform a drying to constant weight, the protein and fat were determined with the Kjeldahl and Soxhlet methods, respectively, and the ashes were obtained with a calcination muffle furnace. The carbohydrates were calculated by difference, and the mineral content was determined by sample digestion using the standard analytical methods for plant tissue. Here, the evaluated parameters were the content of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and iron (Fe).

All the collected data for growth, biomass, and nutritional content was organized and processed in Microsoft Excel 2021. Before comparing the information of the treatments, a Shapiro–Wilk normality test was applied, as well as a variance homogeneity test. Later, the data was analyzed with a one-way ANOVA test and with a Tukey test (p < 0.05) to determine if there were significant differences between the two light treatments. A table containing the significant differences was created in Excel to help with the visualization of the results obtained.

3. Results

A photograph of the interior of the growth chamber is shown in

Figure 5. Here, it is possible to appreciate both lighting treatments being applied to the Swiss chard crops. On the left side of the photograph, we can see the red–blue-predominant full spectrum light treatment (T1). Meanwhile, on the right side, we can see the full-spectrum lighting system (T2) composed of the white, red, blue, and IR/UV spectra. The experimental setup inside the growth chamber shows the following: (A) the air conditioning system, (B) the hydroponic systems highlighted with a dashed line, (C) the humidifier, and (D) the pumps of the hydroponic system.

A close-up view of the lighting treatments is shown in

Figure 6, where (A) displays a group of chard crops being illuminated with treatment T1, while (B) corresponds to light treatment T2. To the naked eye, it is noticeable that treatment T1 favors both the shoot and the stem of the chards. However, with treatment T2, the chards achieve a uniform growth and develop wider leaves. Based on these behaviors in the light treatments, it is possible to assume that light has a direct influence on the morphological development of the chards. Although there was not a physical division between the two lighting treatments, the gap shared by both treatments was 200 cm. To discard any interference between the treatments, we also measured the PPF in each layer’s side, perpendicularly to the axis along the hydroponic channel. Here, it was verified that, as the distance increased, the PPF decayed; i.e., as in the middle of the channels in the corresponding layer, there was a PPF of 230 µmol·m

−2·s

−1, and this value decreased to 40 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 after moving off by 15 cm. Then, it is possible to confirm the non-existent interference between the proposed lighting treatments.

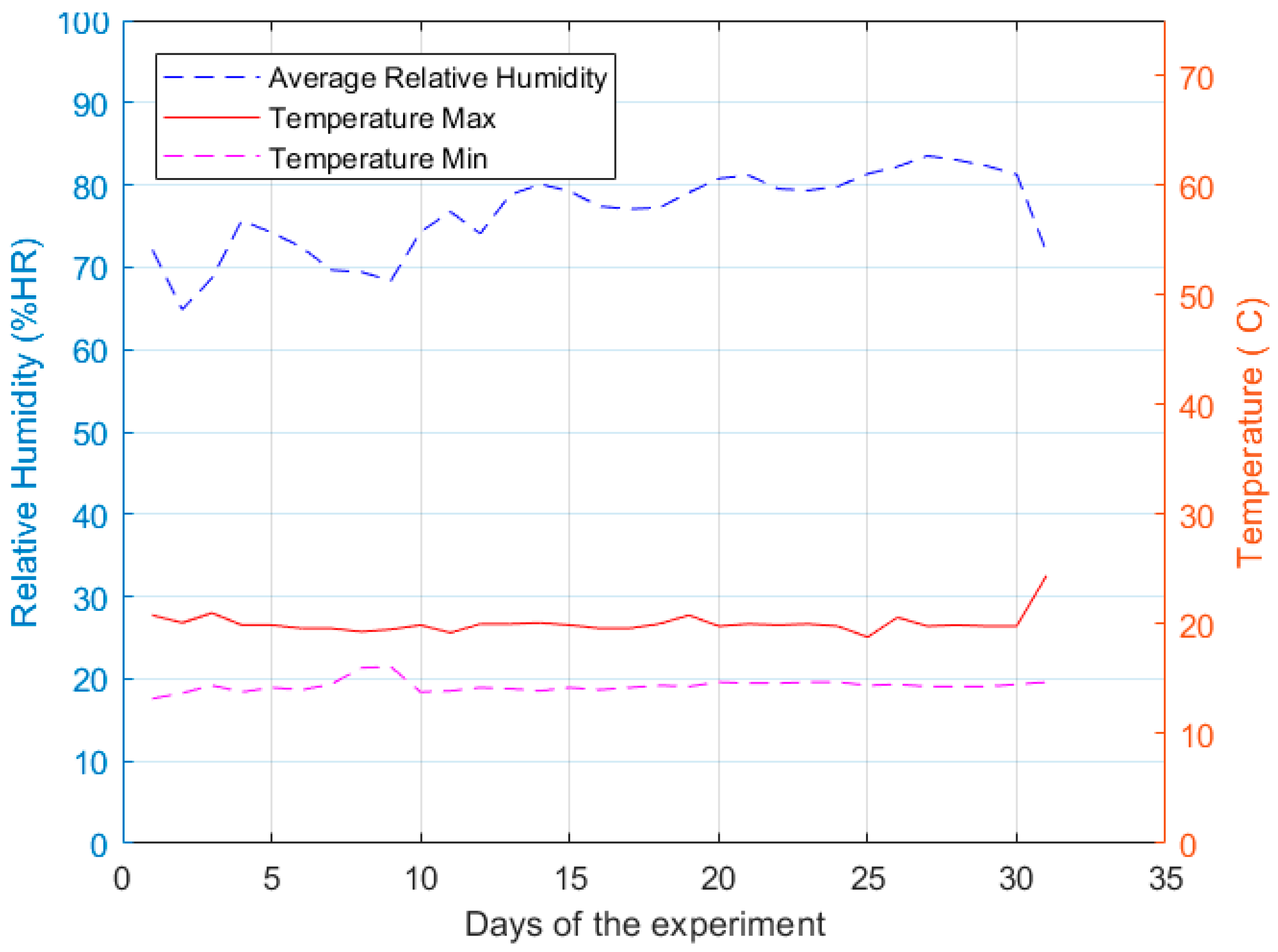

In

Figure 7, the behavior of the temperature and relative humidity inside the growth chamber are shown for the days that lasted the cultivation cycle. The growth chamber had an average temperature of 17 °C ± 2 °C, where the minimum temperature for the cultivation cycle per day is delimited with the dashed magenta line in

Figure 7, and the maximum temperature per day is delimited with a continuous red line in the same figure. On the other hand, the relative humidity had an average of 70% ± 5%, whose mean values per day are indicated with the dashed blue line in

Figure 7.

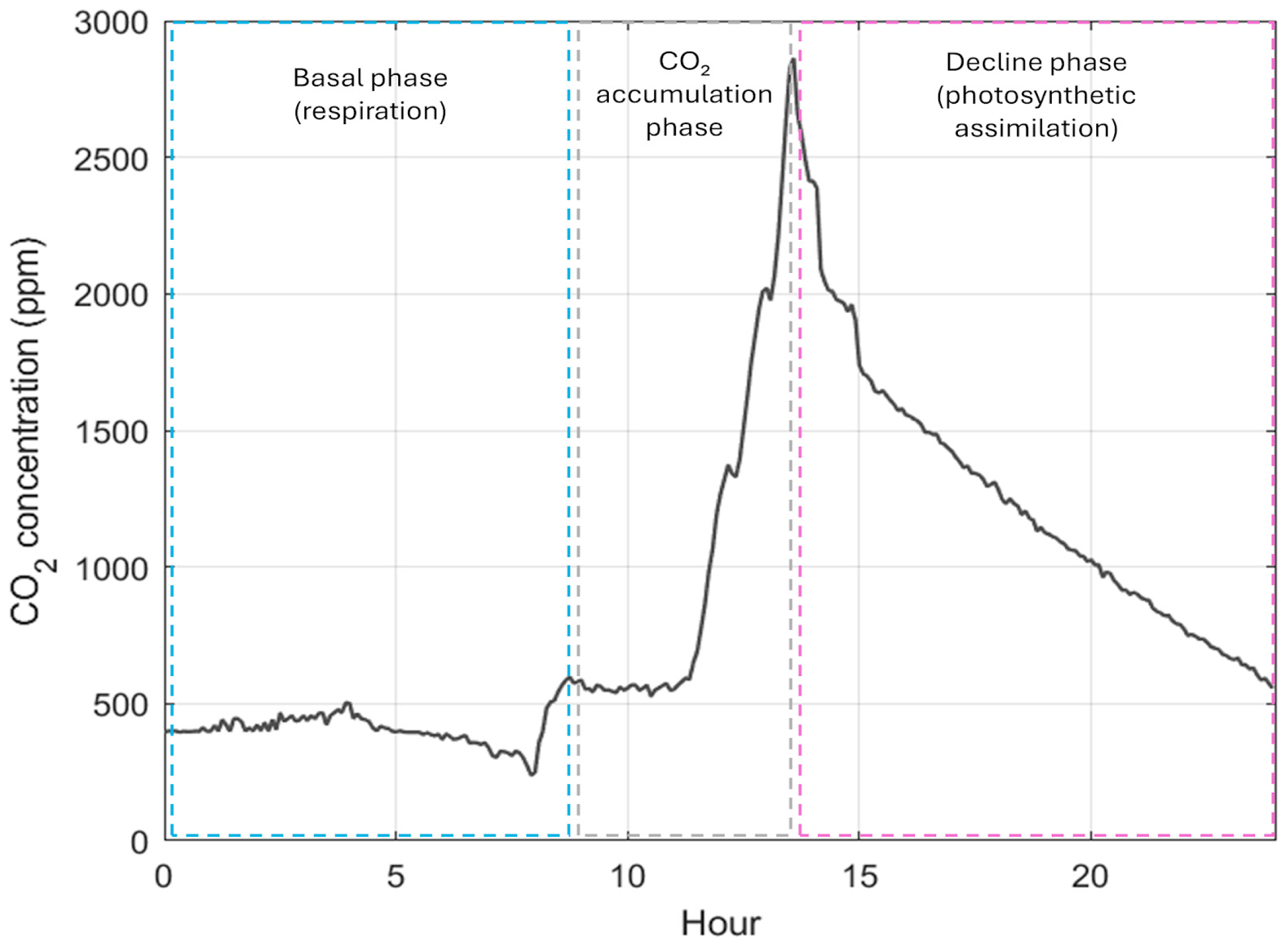

The CO

2 concentration values during the cultivation cycle for this experiment is shown in

Figure 8, where each of these three phases are framed with a dashed blue rectangle for the basal phase, a dashed gray rectangle for the accumulation phase, and a magenta dashed rectangle for the photosynthetic assimilation phase. Particularly, the average CO

2 concentration was 741 ppm for this study, which is within the recommended range (700–900 ppm) for crops being cultivated with biotechnologies [

31]. It was found that this CO

2 concentration in the growth chamber was dependent on the biomass quantity allocated inside the chamber and favored the photosynthetic process without affecting the crops being grown. In particular, the CO

2 behavior was plotted based on three phases: the basal phase, the accumulation phase, and the photosynthetic assimilation phase (declining phase). In the basal phase, the plants not only reflect a breathing phase but also present microbial activity. It is important to note that the basal phase lasts all night, and, during this phase, the CO

2 concentration in the environment is preserved between 400 and 500 ppm. After the basal phase has ended, the accumulation phase begins with human activity inside the growth chamber [

32]. This phase becomes relevant as it promotes the increment of CO

2 concentrations inside the room, allowing compensation for the high demand of CO

2 and preventing a descent in its concentration below the minimal recommended values. Finally, the photosynthetic assimilation phase appears after turning on the lighting systems. In this phase, the CO

2 concentration decreases progressively due to its consumption by chard crops during photosynthesis. This phenomenon goes in line with the literature, as it has been reported that the CO

2 concentration can descend to values between 150 and 200 ppm for indoor systems [

33].

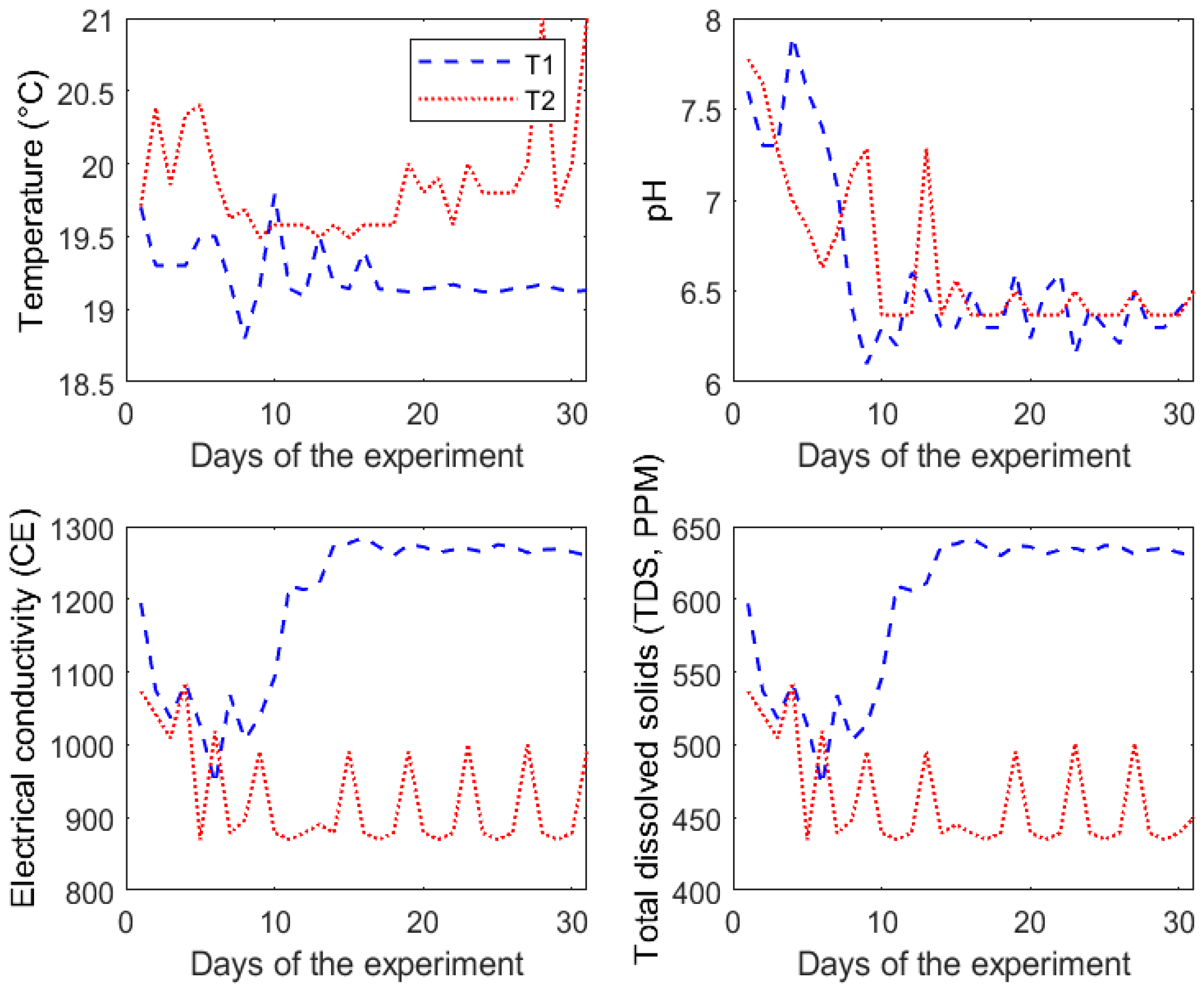

3.1. Behavior of the Nutrient Solution

The nutrient solution used to irrigate the chards was monitored throughout the entire experiment, including its key characteristics such as pH, temperature, electrical conductivity (EC), and parts per million (ppm). First, the mean pH values were 6.61 and 6.65 for treatments T1 and T2, respectively. Second, the mean temperature of the nutrient solution for treatment T1 was 19.2 °C; meanwhile, the temperature for treatment T2 was of 19.8 °C; these temperatures had a similar behavior to the average temperature inside the chamber (17 °C ± 2 °C). Third, the EC for treatments T1 and T2 had average values of 1196 µS·cm

−1 and 927 µS·cm

−1, respectively. Finally, treatment T1 presented 597 ppm and treatment T2 presented 462 ppm on average. In

Figure 9, the complete behavior of the variables described above is presented.

It is important to mention that the temperature values of the nutrient solution (≈19–20° C) above the temperature inside the chamber (17 ± 2 °C) has been found to be beneficial as it promotes the metabolic activity of the roots, favoring the absorption of nutrients. This phenomenon remains valid as long as the temperature is kept between 18 °C and 22 °C; otherwise, a temperature outside this range could have a negative effect on the root’s health [

34]. As the temperature and EC can influence the growth development of the crops, maintaining a continuous monitoring of these parameters of the nutrient solution becomes essential.

As seen in

Figure 9, the nutrient solution used for each treatment had different behaviors throughout the 30 cultivation days. Despite having the same procedure of adjustment for nutrient solutions of both lighting treatments, the variations observed were due to the physiological response of the plants. Accordingly, this difference is a consequence of the photosynthetic process propitiated by the lighting system, where treatment T2 stands out by accelerating the nutrient absorption. The ppm values were calculated from EC measurements using a fixed conversion value; therefore, EC and ppm show a similar behavior but with a proportional tendency.

During the cultivation cycle, the nutrient solution consumption was 1.5 L plant

−1 for treatment T1 and 2.2 L plant

−1 for treatment T2. Particularly, treatment T1 required 110 L of water, 22 mL of nitric acid for pH adjustments, and 1.1 L of nutrient stock. Comparatively, treatment 2 demanded 160 L of water in total, 32 mL of nitric acid for pH adjustments, and 1.6 L of nutrient stock. While some studies report a nutrient solution consumption of 1.8 ± 0.4 L kg

−1 for lettuce cultivated in controlled environments [

35], and 150 L of water consumption in the cultivation of four lettuces for a 41-day cultivation cycle using an LED-based lighting system [

36], similar reports have not been found of the consumed resources during the cultivation of Swiss chard with similar techniques.

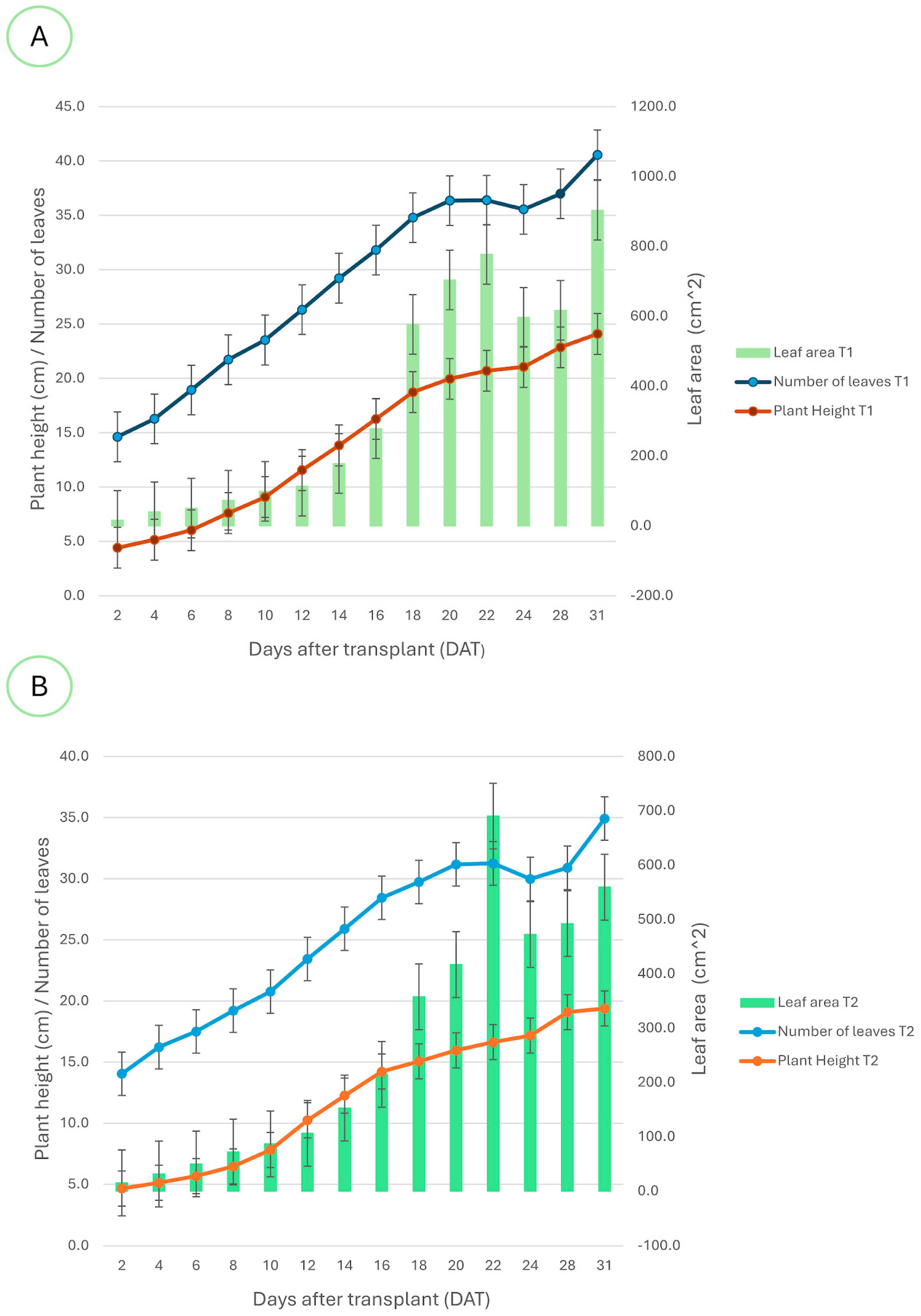

3.2. Morphological Development

To illustrate the healthy and uniform growth for the cultivated Swiss chards in the chamber,

Figure 10 shows a chard exposed to treatment T1 as an example. Here, the growth evolution for the selected Swiss chard starts from the first day after transplanting (top left photograph in

Figure 10) and concludes with a photograph captured on the harvesting day (right photograph in

Figure 10).

As can be seen in

Table 2, most of the morphological and physiological measures did not show statistically significant differences between treatments T1 and T2 (

p ≤ 0.05), including the number of leaves, fresh mass, chlorophyll, shoot, stem width, dry mass, and water content. On the contrary, the foliar area showed a significant difference in favor of treatment T1 with 228.3 cm

2 versus 183.9 cm

2 for treatment T2 (

p ≤ 0.05). Similarly, the radicular length presented a significant difference, where the chard crops exposed to treatment T2 reached an average radicular length of 34.5 cm against the 29.0 cm radicular length for the chard crops exposed to treatment T1 (

p ≤ 0.05). Despite not finding a significant difference, treatment T1 stood out with a higher average for the number of leaves (14.6) and fresh mass (60.3 g) versus treatment T2. Alternatively, treatment T2 had a higher content of chlorophyll (49.6 SPAD) than treatment T1 (45.2 SPAD) even though there is no significant difference present. Conclusively, both light treatments allowed an adequate morphological development for the cultivated Swiss chards.

The plot of

Figure 11 shows the behavior for the Swiss chards’ growth for both lighting treatments, presenting the evolution of the foliar area, the number of leaves, and the height since the first day after transplanting. The A subplot in

Figure 11 corresponds to treatment T1, where the foliar area is represented with the green bars, the number of leaves with the blue line, and the height with the red line. In particular, the chards’ height (red line) showed a progressive increment starting from 4 cm and ending with 24 cm on the 31st day after transplanting, where the highest increment rate was present between 10 and 20 days after transplanting. Similarly, the foliar area (green bars) had a higher increment rate between these days, reaching an average value of 900 cm

2 at the end of the cultivation cycle. Moreover, the number of leaves (blue line) increased progressively to reach a maximum average of 40 leaves, settling down around 24 days after transplanting. This effect can be explained by a senescent process, where the chard begins to lose mature leaves to allow the growth of new foliage; this behavior indicates the time for harvesting. On the other hand, the B subplot in

Figure 11 shows the growth behavior for treatment T2, where the chards presented a lower growth rate for their height (orange line) in comparison to treatment T1 between 10 and 20 days after transplanting. The chard crops under treatment T2 also began with an average height of 4 cm, but ended with an average height of 19 cm. Despite treatment T2 presenting an accelerated increase in foliar area to reach a value of 690 cm

2 after 22 days after transplanting, the average decreased to 559 cm

2 on the harvesting day. This behavior suggests that the chards exposed to treatment T2 had a minor capacity for foliar expansion and biomass accumulation in comparison to the group of chards exposed to treatment T1.

3.3. Nutritional Content Analysis

In particular, the analysis of the nutritional content for the harvested Swiss chards for both treatments T1 and T2 showed significant differences in most of the nutrients except for fat. After applying a Tukey test, treatment T1 presented significant differences against treatment T2 with higher values for carbohydrates (4.7%), sugars (1.3%), dietary fiber (3.3%), protein (2.1%), calcium (67.0 mg), iron (2.6 mg), magnesium (98.2 mg), manganese (0.39 mg), phosphorus (38.6 mg), potassium (631.4 mg), zinc (0.33 mg), and sodium (20.57 mg). On the contrary, treatment T2 showed a significant difference in the water content, 93.0%, versus 92.1% for treatment T1. Conclusively, the Swiss chards grown with light treatment T1 present a higher nutritional content compared to the Swiss chards grown with light treatment T2. These accumulations of nutrients for the Swiss chards grown under treatment T1 suggest a better photosynthetic efficiency and radicular nutrient absorption by the chard crops.

Table 3 shows all the average values for the nutritional content of both treatments.

Table 4 presents a comparison of the nutritional content of the Swiss chards grown with treatments T1 and T2 against the recommended values of commercial Swiss chards by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) [

22]. As can be seen, both groups of grown Swiss chards in this study are not only equivalent but superior in some nutrition facts to the reference values published by the USDA. For instance, the Swiss chards grown with treatment T1 show a higher nutritional content in some minerals (calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, and potassium), protein, and dietary fiber, as well as a low-fat content. Similarly, the Swiss chards grown with treatment T2 show a higher content in the same minerals than treatment T1 except for manganese (0.33 mg).

3.4. Yield and Energy Efficiency

As a result of the harvesting, it was possible to take advantage of the available space by achieving a volumetric density (

Dm3) of 15.3 plants·m

−3 for both treatments T1 and T2 [

37]. Additionally, each treatment had a light use efficiency (LUE) of 0.53 g·mol

−1 in the case of treatment T1 and 0.57 g·mol

−1 in the case of treatment T2, where it is clear that treatment T1 profited from the photosynthetic active radiation during the cultivation cycle. As in the open field, a LUE of 0.23 g·mol

−1 [

38] has been reported; other cultivation techniques such as greenhouses or vertical agriculture can achieve LUE values of 0.39 g·mol

−1 [

23] and 0.55 g·mol

−1 [

39], respectively. As can be seen, these values demonstrate that the proposed system goes in line with other reports in the literature for similar techniques. These values are lower in comparison to other studies using hydroponic systems, where the authors report an EE between 0.10 and 0.72 kg·kWh

−1 for lettuce cultivation [

40]. Conclusively, the results achieved in this study indicate that it is possible to improve the EE of a system by optimizing the lighting systems, improving the cultivation density, and implementing smart control strategies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Control and Experimental Variability Reduction (Bias Control)

The growth chamber developed for this study was able to maintain favorable conditions of temperature, relative humidity, and CO

2 concentration for growing Swiss chards with an NFT-based hydroponic system while making an efficient use of resources such as water and nutrients. Thus, the system goes in line with other studies using either hydroponic systems or vertical farming, where their systems can maintain a temperature between 22 and 24 °C, a relative humidity between 60 and 65%, and a CO

2 concentration in the range of 400–450 ppm [

41], and the studies recommend a photoperiod for lighting systems with intensities of 100, 150, and 200 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 and working between 12 and 16 h·d

−1 [

1]. It is important to mention that, with controlled conditions, the variability of the experiment is reduced.

4.2. Light Use and Energy Efficiency

Since the Swiss chards cultivated were irrigated with the same nutrient solution, which was adjusted equally for both experimental treatments, the differences perceived and reported in this work are a clear result of the exposure of the Swiss chards to different light spectra.

In comparison, light treatment T2 had a better light use efficiency (LUE), at 0.57 g·mol

−1, against light treatment T1, at 0.53 g·mol

−1; consequently, treatment T2 had a higher energy consumption [

42]. As reported in the literature, the red and blue light spectra are responsible for a major photosynthetic efficiency by increasing the electron transferring rate, which promotes physiological responses such as the increment of the foliar area, the root vigor, the biomass, and the soluble sugar content [

43]. Therefore, in treatment T2, the nutrient assimilation favored by the effects of the red and blue light spectra allowed for the increment of biomass production. Despite this increment, treatment T1 had a better energy efficiency, at 0.0159 kg·kWh

−1, compared to 0.0054 kg·kWh

−1 for treatment T2, projecting treatment T1 as a better option due to its efficiency, which can result in an economical benefit by producing more biomass with less energy consumption [

44].

Based on the results, an adequate selection of a lighting system for CEA systems can reduce operational costs without compromising productivity. In fact, this selection becomes relevant as it influences not only the successful development of a crop but also its nutritional quality, which was exemplified for Swiss chard in this work after achieving the main goal of the study, i.e., to evaluate the influence of two different lighting systems on the morphological and nutritional characteristics of the cultivated chards with an NFT-type hydroponic system.

4.3. Use of Space and Volumetric Density

With a volumetric density of 15.3 plants·m

−3, the CEA system used for growing Swiss chard validates a key factor in controlled environments for food production, such as vertical agriculture, after an optimal use of the available space. This result goes in line with other studies maximizing production per unit of area, as in the case of green-leaf crop production for urban environments, which was able to produce crops with a yield of 15 to 1300 crops·m

−2 in the studies [

38].

4.4. Nutritional Quality and Its Comparison to USDA Standards

After analyzing the nutritional content of the Swiss chards cultivated with both light treatments, it can be concluded that both the light spectrum composition and its intensity have a direct effect on the plants’ physiological processes. Particularly, treatment T1 stands out with a higher concentration of carbohydrates, proteins, and minerals, which can be related to the higher nutrient absorption by the roots due to a higher photosynthetic efficiency under the light spectrum conditions for this treatment. Some studies, including [

15], report that the use of both the red light and blue light spectra in the production of lettuce and spinach stimulate the synthesis of antioxidant compounds and biomass gain. Once more, the results in this study for Swiss chard production go in line with these findings, where the group of chards grown with treatment T1 was favored with a higher nutrient content despite not having significant statistical differences in most of the morphological values after a comparison with treatment T2 group. Therefore, the nutritional content achieved by the Swiss chards exposed to treatment T1 is a consequence of the light spectra influencing the photosynthetic process and the nutrient absorption.

Moreover, significant statistical differences were observed only for a few morphological characteristics, where light treatment T1, using 42 W Barina LED bars, favored the increment of the foliar area and the number of leaves; the number of leaves not only was larger than treatment T2 at the end of the cultivation cycle but also showed a higher sprouting rate. Alternatively, light treatment T2 (70 W MURFIN LED) was responsible for favoring a larger radicular length and chlorophyll content; here, the chlorophyll in treatment T2 stood out from both treatments not only with a higher content than the Swiss chard crops of treatment T1 at the end of the cultivation cycle, but also with the generation rate of this pigment through the cycle. By favoring the foliar area for the Swiss chards grown with treatment T1, these chards were able to capture more energy emitted by the lighting system; on the contrary, light treatment T2 favored the physiological processes’ efficiency on each Swiss chard as a result of the larger roots for nutrient absorption and the production of chlorophyll. Given the above, both light treatments presented in this study are adequate for growing Swiss chards but offer specific advantages that can be useful in the development of tailored CEA systems.

Although the grown plants under treatment T1 had higher values for the foliar area, the water consumption was higher for treatment T2. These effects are associated with the radicular length, the chlorophyll content, and the higher water content for the Swiss chards grown under treatment T2, which suggests a better capacity for water absorption and a faster physiological activity. Particularly, the light spectrum composition for lighting treatment T2 promoted the increase in the stomatal conductivity and the development of the radicular system, which was reflected with a higher water consumption by the chards despite presenting smaller foliar areas.

The nutrients and elements that showed higher contents for treatments T1 and T2 in comparison to the USDA reference for Swiss chard in

Table 4 were dietary fiber (3.3% for treatment T1; 2.9% for treatment T2), calcium (67 mg for treatment T1; 57.8 mg for treatment T2), magnesium (98.2 mg for treatment T1; 85.8 mg for treatment T2), and potassium (631.4 mg for treatment T1; 548.7 mg for treatment T2).

Due to the influence of the light spectra in the absorption and distribution of minerals in the chard crops, we observed differences between both lighting treatments in the macro- and micronutrient accumulation. On the one hand, the higher content of macronutrients in the group of Swiss chards exposed to lighting treatment T1 could be associated with higher foliar area values. On the other hand, the variation in micronutrients for this same group shows physiological changes due to the light spectrum quality. It is important to note that, for both lighting treatments, the cultivated chards were accomplished with the recommended values by the USDA.

Additionally, treatment T1 had a slightly higher level of carbohydrates (4.7%) in comparison to the USDA reference (3.74%). In the case of the protein content, its behavior showed a slight variation between the Swiss chards cultivated with both treatments (2.1% for treatment T1; 1.7% for treatment T2) and the USDA reference (1.8%) for this type of green-leaf crop [

22]. Despite the slight variation, it is possible to suggest that the protein accumulation might be influenced by the light spectrum used to grow Swiss chard crops in CEA systems. The water and sodium content were similar among the proposed treatments and the USDA reference, assuring the freshness and turgor of the cultivated Swiss chards. To conclude, LED lighting systems can be used to favorably control the nutritional quality of green-leaf crops to be cultivated in hydroponic systems under a CEA perspective.

Technological Perspective

Finally, the results show that the use of tailored and controlled LED-based lighting systems can enhance the nutritional quality of Swiss chard being cultivated with hydroponic systems. With this, CEA takes more relevance by showing its potential in the production of green-leaf crops with a superior nutritional content not only by taking advantage of the reduced spaces for food production but also by reducing its environmental impact after improving the use of energy and hydric resources, which fulfills the main goal of this type of system [

3]. In addition, IoT monitoring and cloud data management were presented as key tools for a real-time evaluation of the performance reached by the growth chamber. These types of tools lead to an opportunity to create new technologies that empower food production by taking advantage of real-time data in decision-making for CEA systems.

5. Conclusions

This work demonstrated that the proposed green-wall hydroponic system using an NFT configuration and a controlled environment presents an efficient alternative for producing Swiss chard. This efficiency was achieved after an optimal use of the available resources to accomplish a harvest of Swiss chards with a rich nutritional content.

Finally, the energy efficiency (EE) achieved for this study is 0.0159 kg·kWh−1 for treatment T1 and 0.0054 kg·kWh−1 for treatment T2. Both LED lighting treatments (T1 and T2) were beneficial for increasing biomass with a significant LUE; however, T2 required a higher amount of energy to fulfill these benefits. On the contrary, T1 appears as an optimal and sustainable solution after showing a lower energy consumption and producing Swiss chards with a richer nutritional content of carbohydrates, proteins, and minerals.

With a volumetric density of 15.3 plants·m−3, an efficient use of the available space in the green-wall allocated in the growth chamber was preserved. Consequently, this system arises as an alternative for CEA to contribute to food safety and to the sustainable production of green-leaf crops. In addition to volumetric density, the selection of adequate LED lighting systems helps us to develop sustainable agricultural systems after increasing productivity and improving energy efficiency.

The results presented in this work go in line with previous studies such as [

3], where the authors note the relevance of hydroponic systems on food safety and sustainable agriculture. Additionally, the relevance of integrating emergent technologies is widely shared as a key factor in the revolution of modern agriculture to increase its production.

Finally, the evaluation of different lighting systems considering their arrangement and photoperiod under a controlled environment (including light intensity regulation) appears as an extension of this study. This will allow us to explore new techniques to improve energy efficiency and the analysis of other alternatives to favor the green-leaf crops’ growth with a richer nutritional content.