1. Introduction

Effective policy formulation is essential to address social, economic, environmental, and other challenges in order to achieve positive outcomes for individuals and society through the promotion of economic growth, protecting public health and safety, and advancing social justice and equality. The policy formation process has been defined by many scientists and practitioners as the process by which governments and/or other organisations develop policies for decision making and the implementation of decisions and actions. The policy formation process refers to the sequential stages involved in formulating, implementing, and evaluating policies, including problem emergence, agenda-setting, consideration of options, decision making, implementation, and evaluation [

1]. The various segments in the policy formation process demonstrate its complexity and interrelated stages. Policy implementation processes may vary depending on the size of organisations, with the potential for considerable imperfections in applied policy planning and implementation in huge transnational mechanisms such as the EU and other transnational alliances. Established political governance structures such as the EU, with their enlargement, have made policy formation increasingly complicated due to their increased scope and depth [

2,

3,

4]. The recent development trends of various regions in Europe call for a new generation of reflective policy and governance structures based on citizens’ needs [

5].

Stakeholder engagement is often cited as a solution to the identified challenges of policy formation processes [

6,

7]. Engaging stakeholders in the policy-formation process should follow specific conditions of communication, ensuring that this communication is uncorrupted by power differences and strategic motivations [

8]. Andriof et al. [

9,

10] highlighted that unfolding stakeholder relationships—especially emerging processes for stakeholder engagement—can best be understood by integrating corporate social performance/responsibility, stakeholder, and strategic relationship theories. This provides a framework that can enhance our understanding of the dynamics of and rationale for the increased levels of stakeholder engagement witnessed [

9,

10]. Stakeholder engagement creates interactive, mutually engaged, responsive relationships that provide a basis for transparency and accountability.

Stakeholder engagement is equally important for various organisations, and it is even more challenging for transnational mechanisms such as the EU, with its numerous members and wide variety of policies. The Common Agricultural Policy (the CAP) was introduced in 1962 as one of the general policies of the EU. The CAP constitutes a considerable part of the EU budget, reaching 23.5% in 2022, and in the past 20 years (i.e., in the 2004–2024 period) the CAP budget has increased 2.7-fold, from EUR 141.8 billion to 386.6 billion [

11]. The CAP is one of the major public policies within the EU and has caused arguments and disputes between the different stakeholders included in the process. Lithuania joined the EU in 2004 and, since then, has needed to adopt the EU’s legislation, regulations, and other acts, as well as to follow the EU’s rules and mechanisms for decision making. Since 2004, the CAP has been an important tool for Lithuanian stakeholders, and the CAP’s practices for formulating national Strategic Plans have also changed over the past 20 years. As the development of the CAP and Strategic Plans in Lithuania is only 20 years old, the authors of this paper hypothesise that this period might be too short for finding effective means of stakeholder engagement in the CAP-formation process.

While the importance of effective policy formulation in addressing societal challenges—such as promoting economic growth, public health, and social justice—is well-recognised, there is a growing need to explore how stakeholder engagement specifically influences the policy formulation process within the context of the European Union’s expansion [

12]. Much of the existing literature has focused on general policy formation mechanisms or stakeholder involvement, without addressing the complexities brought about by the EU’s enlarged scope and the need for citizen-centric policies in diverse regions. Furthermore, while the EU’s evolution has increased the scope of policy formation, there is a lack of detailed studies on how these changes specifically affect the integration of reflective governance structures based on citizens’ needs. Thus, a gap exists in our understanding of how stakeholder engagement can be effectively tailored to navigate the complexities of EU policy formation, ensuring that it is both inclusive and responsive to diverse regional developments.

Research carried out by Eaton et al. [

13] emphasised that participatory approaches, including stakeholder engagement, are increasingly common for managing complex socio-ecological challenges. This involvement ensures that diverse perspectives are considered, enhancing the legitimacy and acceptance of agricultural policies. A study by Aarts et al. [

14] highlighted that effective stakeholder communication fosters collaboration, thereby facilitating the application of research outputs to achieve necessary improvements in productivity and sustainability. An article by Kipling and Gülzari [

15] discussed the importance of stakeholder engagement in the perceptions of researchers, noting that substantial improvements in agricultural systems require collaborative partnerships between research producers and consumers. Such collaboration leads to the more effective application of research outputs, thereby improving transparency and efficiency in policy development. Moreover, one of the most recent EU initiatives, “Strategic Dialogue on the Future of EU Agriculture” [

16], serves as a forum for farmers and key stakeholders across the agri-food chain to share their perspectives, ambitions, and solutions. This dialogue aims to establish a shared vision for the EU’s farming sector, emphasising the role of stakeholders’ inputs in policy development. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that integrating stakeholder engagement into agricultural policy development is essential for creating transparent, efficient, and effective policies that are responsive to the needs of all participants in the agricultural ecosystem.

The main aim of this research is to reveal the design of national Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Strategic Plans (hereafter referred to as “SPs”) in Lithuania and demonstrate the shift towards more openness, collaboration, and inclusion of different stakeholders, as well as to offer future solutions for a more open and evidence-based CAP and national SPs. The main research problem is the insufficient involvement of stakeholders in the policy formation process, which leads to less effective policy implementation results.

This research helps us to identify experiences of stakeholder engagement in the policy formation process for the design of national Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Strategic Plans in Lithuania, as well as reflecting on the research gap, the success of stakeholder engagement in this process, and the need for policies that reflect citizens’ needs.

The main objectives of this study are as follows:

− To define the importance of stakeholder engagement in the policy formation process;

− To describe challenges of the CAP SP process in the EU;

− To define existing attitudes towards the engagement of relevant stakeholders in the process of preparing the Lithuanian Rural Development Programme 2023–2027 in terms of the flexibility, transparency, inclusivity, and effectiveness of organisation and management.

Multi-stakeholder approaches were applied to assess stakeholder engagement in the process of the CAP’s formation. This research was organised using qualitative research principles by selecting experts using the quadruple helix approach [

17] and organising focus group discussions of the identified research questions.

This research paper is organised in four sections. Firstly, an introduction to the topic is provided by highlighting the importance of stakeholder engagement in the policy formation process. Secondly, the materials and methods are explained by (i) giving an overview of stakeholder engagement in policy formation processes, including agriculture policy formation; (ii) analysing the CAP’s preparation process in the EU and the importance of stakeholder engagement therein; and finally, (iii) describing our research design. In the following sections, our research results and discussion are presented.

3. Materials and Methods

The main aim of our research was to define existing attitudes towards the engagement of relevant stakeholders in the preparation process of the Lithuanian Rural Development Programme 2023–2027, in terms of the flexibility, transparency, inclusivity, and effectiveness of organisation and management. To achieve this aim, multi-stakeholder approaches were applied to assess stakeholder engagement in the process of the CAP’s formation. This research was organised using qualitative research principles, selecting experts using the quadruple helix approach, and organising focus group discussions on the identified research questions.

The quadruple helix innovation approach [

17] was used to identify key groups of stakeholders active in the formation of national CAP SPs. Usually, those key groups can be divided into 4 categories: private organisations (i.e., farmers, producers, processors, the agri-food industry, and cooperatives, as the primary beneficiaries and implementers of CAP measures), governmental organisations (i.e., national and regional governments, ministries of agriculture, and other relevant public institutions, which are central to designing and approving the plan in alignment with EU regulations and national priorities), research organisations (i.e., universities, research centres, and think tanks, which provide evidence-based recommendations to improve the effectiveness, sustainability, and innovation of agricultural practices and policies), and non-governmental organisations (NGOs; i.e., representatives of rural communities, environmental agencies, ecologists, and advocacy groups, which ensure that the plan addresses social inclusion, sustainability, and the needs of marginalised groups). However, in the case of policy formation, the participation of the private sector is limited to a certain extent, as private companies usually express their interests through associations and umbrella organisations, and sometimes through public consultations or lobbying and advocacy efforts. Therefore, private organisations per se were excluded from the focus group, but their voice was represented through the NGO sector.

Seeking to map the most relevant stakeholders, the stakeholder salience model [

45] was employed, and possible stakeholders were assessed using 3 criteria: power, urgency, and legitimacy, considering their influence and experience in the formulation of national SPs. For inclusion in the focus group, we selected those stakeholders that met at least two criteria, i.e., power and legitimacy (dominant); power and urgency (dangerous); legitimacy and urgency (dependent); or power, legitimacy, and urgency (definitive) [

45,

46] (see

Table 1). This selection of stakeholders is important in trying to include those who can influence the decision-making process in the field.

A developed map of the most relevant stakeholders was used for the selection of the most relevant participants in the focus group, leaving 15 out of 37 selected in the first step.

Of these 15 stakeholders, 12 took part in focus group, representing governmental organisations, research organisations, and non-governmental organisations. Stakeholders from the private sector, as mentioned above, were not included directly, as they could overlap with lobbying activity, but their voice was represented through non-governmental organisations, such as various unions and/or umbrella associations. Twelve participants attended the focus group meeting, which was held on 7 November 2023 in Vilnius. The participants represented three categories of stakeholders: science, policy, and society, with each group comprising an equal proportion (33.3%). Gender balance was also taken into account, with the participants being 66% women and 34% men (

Table 2).

A focus group discussion was selected because, as summarised by Ochieng et al. [

47], this is a good tool to generate discussion or debate about a research topic that requires collective views and the meanings that lie behind those views (including their experiences and beliefs), as well to explore a topic and obtain information or narratives [

47]. Therefore, the main goal of the focus group was to deepen and expand our knowledge of the engagement of relevant actors in the preparation process of the national Strategic Plan (SP) in Lithuania, in terms of the flexibility, transparency, inclusivity, and effectiveness of organisation and management. Four key questions were addressed to the participants in the focus group discussion:

What tools can be identified in the design and implementation of the CAP Strategic Plans?

How would you assess the functionalities of the tools?

What are the challenges faced by policymakers in the different SP steps for which they have used monitoring and data collection tools?

What are the policymakers’ and end-users’ needs in improving or adopting new tools?

The information gathered from the focus group discussions was analysed using a number of standard qualitative analytical techniques [

47]. Initially, each discussion transcript was read and annotated. The information was then placed in context, and the gathered data were segmented. The segments were then examined, and the research questions were addressed through interpretation of the findings. The

Section 4 provides a detailed explanation of the data analysis based on the questions and steps that have been presented thus far.

4. Results

The results revealing the engagement of relevant actors in the preparation process of the national SP in Lithuania, in terms of the flexibility, transparency, inclusivity, and effectiveness of organisation and management, are presented in this section. The results are divided into four subsections, based on the logic that was established in

Section 3.

4.1. Tools Identified in the Design and Implementation of the Cap Strategic Plan

The focus group discussion revealed that the tools most frequently applied for the design and implementation of the CAP Strategic Plan in Lithuania in recent years have been focus groups, cumulative voting, expert judgement, socioeconomic analysis, and comparative analysis. More rarely, scenario building (or scenario modelling) has been applied as an informative tool.

It was agreed that, as each of these tools is viewed as an independent entity carrying out its duties in the SP design and monitoring processes, none of them produce any repetitions or duplicates.

The listed tools are used in a particular sequence or design and implementation of SP policy steps. Typically, the process starts with tools that can provide evidence-based solutions for setting the directions of priorities according to the approved government programme in action, and in parallel with a normative national and supranational legal basis. Essentially, this entails socioeconomic analysis based on existing datasets, socioeconomic indicators, and other available data. These are used for defining the country-specific socioeconomic context of various issues under examination, and for grounding the SWOT analysis. Comparative analysis is employed when identifying the need for intervention, and for setting the areas of intervention. Focus groups are organised to elucidate the existing needs of different stakeholders. Aiming to develop a list of the most relevant needs in different areas, stakeholders are further grouped for discussions according to their fields of interest and topicality. Furthermore, the cumulative voting approach is applied in the SP design phase when setting the priorities among the overall identified needs or stakeholders, in order to prioritise the goals of the SP. When there is a need for fast, on-demand consultations on specific themes or concerns, expert judgement is employed as an essential tool throughout the entire SP design and monitoring process.

An additional tool used in the public policy design phase is scenario building, or scenario modelling, which is relevant in many policy areas and countries (e.g., [

48]), but it has also been used in modelling the CAP Strategic Plan in Lithuania [

49,

50]. The focus group (participants representing the policy helix) revealed that this tool was useful for the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Lithuania, as it led to constructive, scientific-evidence-based discussions with various stakeholders when setting the CAP’s priorities and defining measures, and it played a key role in ex ante political agreement regarding the possible and most acceptable socioeconomic context development trends, along with other issue-specific topics. The majority of the focus group members agreed that this led to the construction of a more realistic and precise SWOT analysis and prioritisation, allowing for a less politicised and more scientific-evidence-based understanding of future context-specific policy objectives and goals among stakeholders, alongside a more realistic and implementable, Lithuania-specific, possibility-and-need-based CAP. However, a few members of the focus group noted that scenario building/modelling is expensive and time-consuming and that it is, therefore, increasingly rarely applied in the SP design and implementation process. Nevertheless, the society stakeholders highlighted that they were more satisfied with previous practices of applying this tool in the political process, as it leads to much more transparency, trust, and commitment due to its objective, evidence-based nature.

4.2. Functionalities of the Tools

The focus group came to the conclusion that the accuracy of the results provided depends on the specific tool. Focus groups are one example of a flexible and inclusive tool that can be used for a variety of purposes. Depending on their composition, they can even be utilised as a political tool. Although focus groups are a useful technique for gathering diverse viewpoints, they may also be highly politicised, because each participant represents a particular interest and works toward achieving that goal. Because it shares the same drawbacks as focus groups, the cumulative voting approach also seems to be a somewhat political tool. As such, these tools should be used “to measure the temperature” of the stakeholders rather than to support future policies. It was also agreed that focus groups are a reliable tool to ensure the inclusion of various stakeholders and to gather different points of view.

However, the focus group did acknowledge that other methods, such as expert judgement, comparative analysis, and socioeconomic analysis, are more reliable, transparent, and produce useful results. According to the focus group participants, the issue is typically not the tools’ accuracy but, rather, the circumstances in which politicians attempt to persuade all stakeholders without having any clear strategic objectives.

During the discussion on functionalities, such as the frequency of tools’ updates and the ability to provide feedback, the focus group agreed that all tools are updated as needed and in a timely manner. The Strategic Plan (SP) is regularly updated, along with the tools that support its implementation. Comparative analyses are conducted on a routine basis, and the National Paying Agency provides data on various indicators. These data serve as the foundation for refining and updating policies to achieve optimal outcomes.

When discussing the tools’ adaptability to various contexts, specific objectives, or even policy areas outside of the CAP, the majority of the focus group deemed that the aforementioned tools could be modified to fit various situations. This was the case in Lithuania when preparing the SP, where ten focus groups were conducted in accordance with nine specific objects and one horizontal objective related to the AKIS. Our focus group also pointed out that because policies are often somewhat related and overlap, it is crucial to utilise a variety of methods in order to assess the situation and evaluate the country’s agricultural policies as a whole.

The focus group concluded that ease of use is entirely dependent on the particular tool. Focus groups, for instance, are among the most challenging to set up, since they demand a lot of organisational and management resources and the dedication of stakeholders. Because there are more stringent methodological standards, and because data analysis, comparative analysis, expert judgement, and socioeconomic analysis are based on the knowledge of scholars and experts rather than the interests of stakeholders, they are simpler to employ.

The focus group also discussed budgetary concerns and came to the conclusion that the cost of the tools varies depending on the particular instrument. According to a few of the focus group participants, the use of focus groups is among the most challenging techniques, since they are hard to plan, require a long time to conduct, analyse, and summarise the conversations, and rarely result in recommendations of the best policies for all parties involved.

4.3. Challenges Faced by Policymakers in Developing the CAP SP

Five main challenges faced by Lithuanian policymakers in the different SP steps were identified: time constraints; the volume of CAP SP documentation; communication on the CAP SP preparation and implementation process; and data coverage, availability, and relevance.

Time constraints: The focus group discussion revealed that although the overall timeline for the design of the CAP Strategic Plan (SP) was relatively extended, the application processes of individual tools were carried out hastily. This constrained the opportunity to organise the number of scientific-evidence-based focus group discussions that would have been necessary to achieve consensus among all stakeholders on various issues. Consequently, the time limitations hindered the use of less frequently applied but highly informative and valuable tools, such as scientific-evidence-based analyses grounded in the most recent socioeconomic data, as well as scenario building and modelling. Instead, focus groups and expert judgement emerged as the most frequently utilised tools due to their timely, on-demand application and relatively straightforward organisation.

Volume of CAP SP documentation: The national CAP Strategic Plan (SP) documentation is highly voluminous, comprising approximately 800 pages in total. This extensive scope poses significant challenges for stakeholders to provide meaningful feedback or suggest improvements. The document’s size and complexity, coupled with the lack of clear referencing for changes made throughout the design process, further exacerbate these difficulties. Additionally, no systematic summaries are provided on recent updates, making it challenging for stakeholders—even those who are highly engaged—to review and reflect on the documentation effectively during public consultations.

To address this issue, experts have proposed the establishment of a new tool, such as a “CAP SP Radio Channel”, which would regularly communicate the most recent developments in the preparation and implementation of the national CAP SP. This channel could provide updates on the current policy steps, details of ongoing discussions, requirements for public consultations, and clear guidance on how stakeholders can participate efficiently. A pilot initiative of this kind has already been launched by the Lithuanian National Paying Agency in the form of the “National Paying Agency Radio” [

51], which shares critical updates about the ongoing payment period and other relevant programme information. This concept could serve as a model for improving stakeholder engagement and communication in the CAP SP process.

Communication on the CAP SP preparation and implementation process: The communication tools currently used for the preparation and implementation of the CAP Strategic Plan (SP) are overly static and outdated, limiting their effectiveness in conveying information across all stages of the policy process. While the European Commission’s mandatory requirements for public communication regarding CAP SPs have been fully met, the information provided on various websites remains overly static, voluminous, and insufficiently systematised. Although specific information is available, considerable time and consultation are often required to locate the relevant details. Recent advancements in the organisation of the Agricultural Knowledge and Information System (AKIS) are anticipated to provide a prospective solution. The development of an open-access, keyword search engine-based tool within the AKIS could significantly improve the accessibility and retrieval efficiency of relevant information, thereby enhancing the overall communication process for CAP SPs.

Data coverage and availability: A substantial volume and variety of relevant, timely data are collected through Eurostat and national paying agencies, covering agricultural and rural development issues as well as CAP beneficiaries. However, due to the current user-unfriendly interfaces, these data are not fully utilised to inform the design and monitoring processes of the CAP Strategic Plan (SP) and to support evidence-based decision making. To address this, the data platform must be redesigned to enhance its accessibility and usability. Another significant challenge lies in data security and personal data protection constraints. Recent restrictions have rendered large datasets on CAP beneficiaries and sectoral development unavailable for analysis, limiting their utility in both the CAP design and monitoring phases. Fragmented trends or issue-specific timelines are insufficient when analysed in isolation, as they lack the broader sectoral context necessary for meaningful insights. Furthermore, while rich scientific evidence on various aspects of the CAP is published in issue-specific scientific publications, these are confined to academic databases, which are inaccessible to non-expert users such as farmers or other stakeholders involved in the design and implementation of CAP SPs. According to the focus group experts, there is a clear need for a dedicated tool—such as a platform or social media channel—that translates scientific findings into user-friendly summaries, thereby facilitating their application in CAP developments and fostering greater stakeholder engagement.

Data relevance: The widespread application of retrospective data analysis tools, often mandated by European Commission (EC) officers, can appear increasingly inadequate in light of the rapid transformations occurring in environmental, legal, and geopolitical contexts. These transformations include climate instability, pandemics, war, and the urgency of achieving a swift green transition, among others. The reliance on classical retrospective socioeconomic development data as a primary tool for future CAP Strategic Plan (SP) design often renders this approach ineffective. For example, while the European Green Deal calls for transformative shifts in CAP SPs at both the national and supranational levels to address climate and environmental changes, retrospective data analysis tools frequently prioritise outdated objectives such as agricultural production increases. Similarly, while maintaining and creating jobs in rural Lithuania is recommended based on retrospective data, this approach fails to account for the drastic population decline in these areas, which has left few individuals available for employment.

Our focus group experts emphasised the need to reconsider the mandatory use of such outdated tools in CAP SP design and monitoring processes; they argued that the current era of rapid and profound change necessitates the adoption of more adaptive and reflective tools. For instance, small-scale agricultural experiments or rural community-based initiatives were identified as valuable alternatives that could provide more relevant, region-specific evidence to effectively guide CAP SP design.

Finally, it must be noted that despite the expressed challenges, the selection of the abovementioned tools in the CAP SP design and implementation process is sometimes defined by the EC as compulsory. Other tools, such as focus groups and expert judgement, are broadly applied due to their timely, on-demand application, less complicated organisation (time constraints), and uncomplicated documentation (focus group protocols). Tools such as socioeconomic analysis and scenario building/modelling are time-consuming, costly, and require expertise.

4.4. Policymakers’ and End-Users’ Needs in Improving and Adapting the Tools

The focus group discussions revealed that there are a few key needs for policymakers when it comes to improving existing tools or introducing new ones. The most important of these needs is for more data, which could be (or sometimes are) collected at the farm level. Large amounts of data are needed to carry out expert judgement, socioeconomic analysis, or comparative analysis, and these data are not always available or easily accessible. Our focus group identified three concerning situations regarding data: in some cases, data are not collected at all; secondly, some data are collected privately (e.g., soil test results), and there is no need for farmers to share them; thirdly, data may be collected by public bodies but be very difficult to access, or there may be GDPR issues. The focus group agreed that it would be a very useful practice to provide incentives for farmers to share the data they collect on their soil quality, fertilisation needs, etc.

The experts also agreed that the National Paying Agency should collect more data from applicants and beneficiaries and try to combine the simplification of applications with sufficient data collection, as there is now a situation where due to the simplification of applications, not many data are required, but they would still be very useful in making decisions on different policies.

Another issue mentioned by the experts representing science and policy is that once data are collected, accessing them is usually very difficult and user-unfriendly, so there is a great need for simplified data accessibility and up-to-date national data platforms. Digital data infrastructure, such as online platforms, is essential for making timely decisions and using the most appropriate tools.

The focus group expressed positive expectations for the reorganisation of the European Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) into a Farm Sustainability Data Network (FSDN), as greater amounts of more relevant data and timely data will be collected. Good-quality data are essential for the introduction or improvement of any tool—especially tools for expert judgement, socioeconomic analysis, or comparative analysis.

Finally, the focus group (especially stakeholders representing policy) expressed concerns about time management and the time allocated to the preparation of the SP and the use of the tools, stating that while it could seem that the time given was sufficient, the tools had to be used quickly at many stages, leaving insufficient time for the data collection and monitoring phase.

5. Discussion

Stakeholder engagement is often used in Lithuania as a tool for the policy formation practices of CAP SPs. This method can be seen as a solution to mitigate the risks of flaws in policy planning and implementation in agriculture and rural development. The results of our research revealed that a multi-stakeholder approach is useful when selecting stakeholders for discussions in the preparation of SPs, resulting in a sense of responsibility among all actors involved in the preparation and implementation phase. Policy implementation in the EU is complicated, with a great potential for imperfections in applied policy planning, due to its enlarged scope and depth, but common tools used in the preparation of CAP SPs can lead to easier and more transparent policy planning and implementation processes. Stakeholder engagement is crucial, as interested parties generate options for the regional authorities responsible for planning and managing agricultural activities.

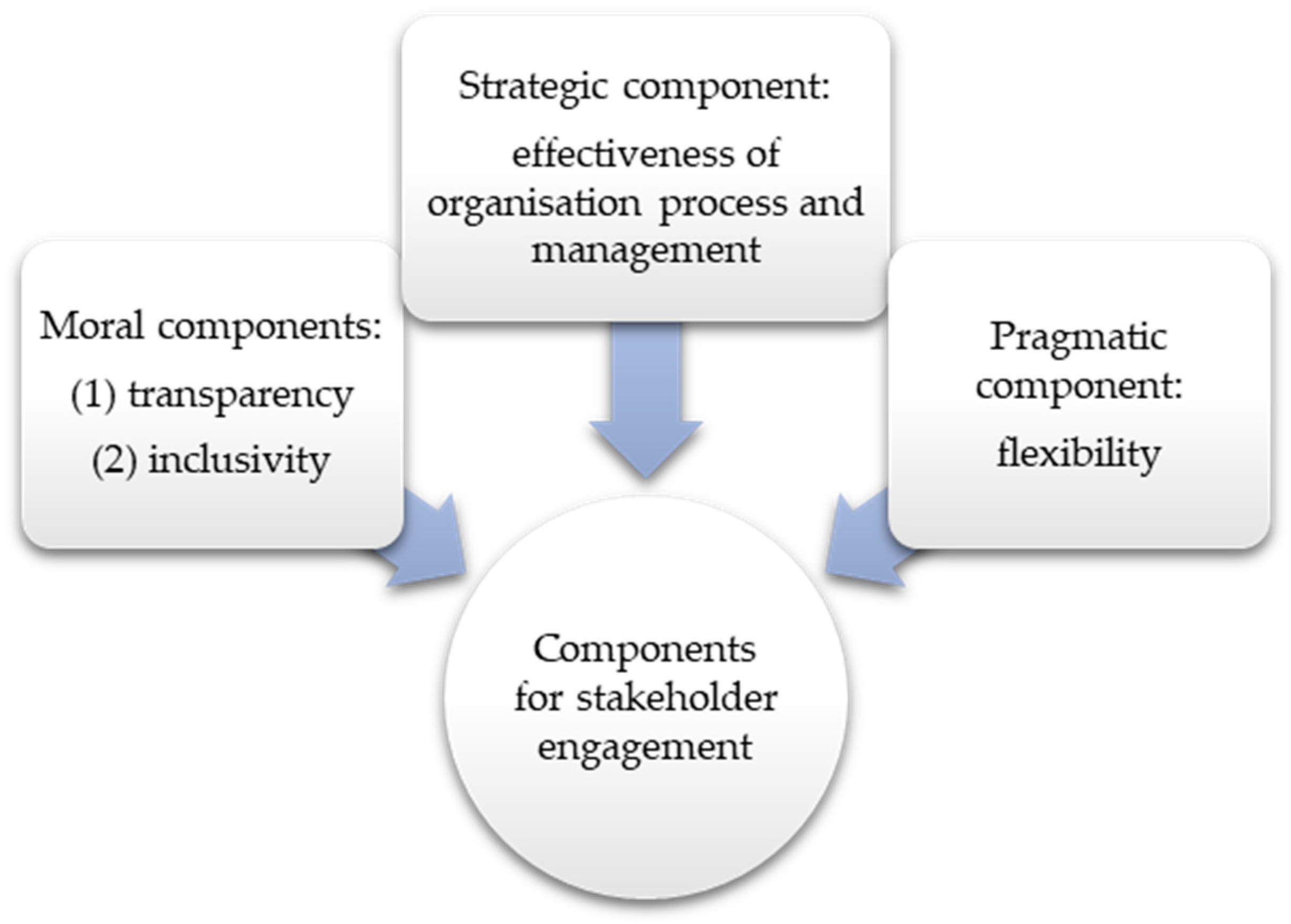

The preparation of Lithuanian CAP SPs demonstrates the shift towards more openness, collaboration, and the inclusion of different stakeholders based on an evidence-based needs assessment and focused on future solutions for more open and evidence-based CAPs and national SPs. Stakeholder engagement in Lithuanian CAP SPs involves moral, strategic, and pragmatic components. Nevertheless, we believe that our findings lend some qualitative support to the hypothesis that 20 years of EU membership is an insufficient duration to determine the most effective means of stakeholder engagement in the CAP formation process, and there is a room for further improvements. Our findings demonstrate that communication between stakeholders in various events must be focused on decreasing power differences and strategic motivations despite the size of the enterprise, membership of specific associations and/or political organisations, etc. Selection of representative stakeholders using the bottom-up quadruple helix approach can be good tool to overcome these challenges.

Analysis of stakeholders’ engagement in CAP SPs in Lithuania revealed that there is a certain middle ground between formalistic (e.g., [

44]) and more elaborated engagement. Moreover, our study confirmed the findings of Helbig et al. [

7], who stated that involving stakeholders in various stages of the policymaking process can enable a simultaneous focus on the substance of the policy problem and on improving the tools and processes of policy development, as the experts in our focus group were able not only to identify tools used in the design and implementation of CAP SPs but also to evaluate the functionalities of the tools, challenges faced by policymakers, and the need to improve and adapt current tools.

However, it must also be mentioned that the current research reveals a certain absence of national initiatives regarding particular local, context-based knowledge. As Oliver et al. [

28] stated, where local contexts are unfamiliar, efforts begin with gathering local knowledge from local stakeholders about the context and how people cope, and this particular aspect is lacking in Lithuania. There could be two main reasons for this: first, an overachiever complex arising from public policy decision makers implementing everything that comes from European Commission regulations despite paying attention to localities and certain local contexts; and secondly, ignorance of local context and, therefore, a lack of adapted solutions and decisions in preparing CAP SPs, and later in implementing certain policies.

It is interesting to note that while the literature (e.g., [

8]) mentions that stakeholder engagement might be corrupted by power differences and strategic motivations, our focus group found that stakeholders were considerate of one another and did not put their own interests and opinions first but participated in the discussion equally. This might be explained by the balance that was achieved in the strength of the stakeholders through the quadruple helix innovation approach and the stakeholder salience model.

Therefore, European decision makers should re-examine the concept of CAP SPs and especially improve the support systems and capacity-building for SP designers. Greater involvement of academic research and scientific methods and tools in the preparation, monitoring, and evaluation of plans could significantly improve the quality of planning. This would require increased investment in research and dialogue among representatives of academia, government, and the non-governmental sector [

44]. Practical implications are relevant to the present research, as the developed theoretical approach and the described methodological approach could be applied to practitioners in any area of the policy formation process. The quadruple helix approach could be used for defining the relevant stakeholders in many policy areas. The findings of this research suggest a meaningful starting point from experts’ views on better and more responsible decision-making practices.

Some research limitations must also be mentioned here. For example, this paper presents empirical findings based on limited qualitative data gathered in one EU member state (i.e., Lithuania). From a theoretical and empirical perspective, international comparative perspectives are given with reference to other related papers. Our research findings are promising for further research in the field of stakeholder engagement using the quadruple helix approach to foster collaboration and inclusive decision-making processes in the preparation of Common Agricultural Policy Strategic Plans.

6. Conclusions

The current research revealed that Lithuanian stakeholders relevant to CAP SPs are eagerly engaged with both decision-making and knowledge production activities, where the most commonly applied tools for the design and implementation of CAP SPs in Lithuania are focus groups, cumulative voting, expert judgement, socioeconomic analysis, and comparative analysis. More rarely, a very informative tool called scenario building (or scenario modelling) is applied. The listed tools are used in a particular sequence of policy steps for the design and implementation of SPs in Lithuania.

The functionality of the tools varies, and it was revealed that focus groups are a good tool to collect different opinions but can also be political, as every member of the focus group represents their own specific interests and seeks to speak for them. However, other tools—such as comparative analysis, expert judgement, or socioeconomic analysis—are more accurate and provide valid results. The focus group participants expressed the view that the primary issue often lies not in the accuracy of the tools themselves but in the absence of strategic goals among policymakers, who instead attempt to persuade experts (e.g., members of the focus group). Consequently, it is essential to implement the selected tools in alignment with best practices and established methodological guidelines. To achieve this, public institutions’ officers and organisers—such as those conducting focus groups—should adhere meticulously to methodological guidelines and continually update their expertise in this domain.

The main challenges faced by Lithuanian policymakers are related to aspects such as institutionalisation issues (i.e., compulsory, predefined national and/or supranational tool exploitation requests), various objective technical constraints (e.g., time, volume, budget, expertise), relevance (e.g., the rationality of taking a long retrospective dataset, its reflectivity to actual ongoing transformations, and the flexibility to empower alternative tools), and general availability issues (e.g., data protection and openness, communication, user-friendly access). To enhance the organisation of the CAP SP, it was determined that policymakers require high-quality and timely national data, user-friendly digital platforms, and improved time management to refine existing tools or adopt new ones.

In summary, the future research directions for scientists and policy practitioners should be threefold: firstly, to provide a shared knowledge base and an evaluation of the methods and tools used for the design and implementation of the SP; secondly, to identify and adopt innovative methods and tools for the design and implementation of the SP, by taking stock of relevant and replicable solutions developed in recent and ongoing research projects and other EU initiatives; and thirdly, empowering end-users to adopt innovative solutions for the design and implementation of the SP through providing them with methodological guidance on choosing the best solutions, their operationalisation, and associated good practices.