Egg Consumption Patterns and Sustainability: Insights from the Portuguese Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability and Consumer Behavior

2.2. Consumer Perceptions and Preferences Regarding Regulations

2.3. Industry and Innovation Challenges

2.4. Egg Consumer Behavior

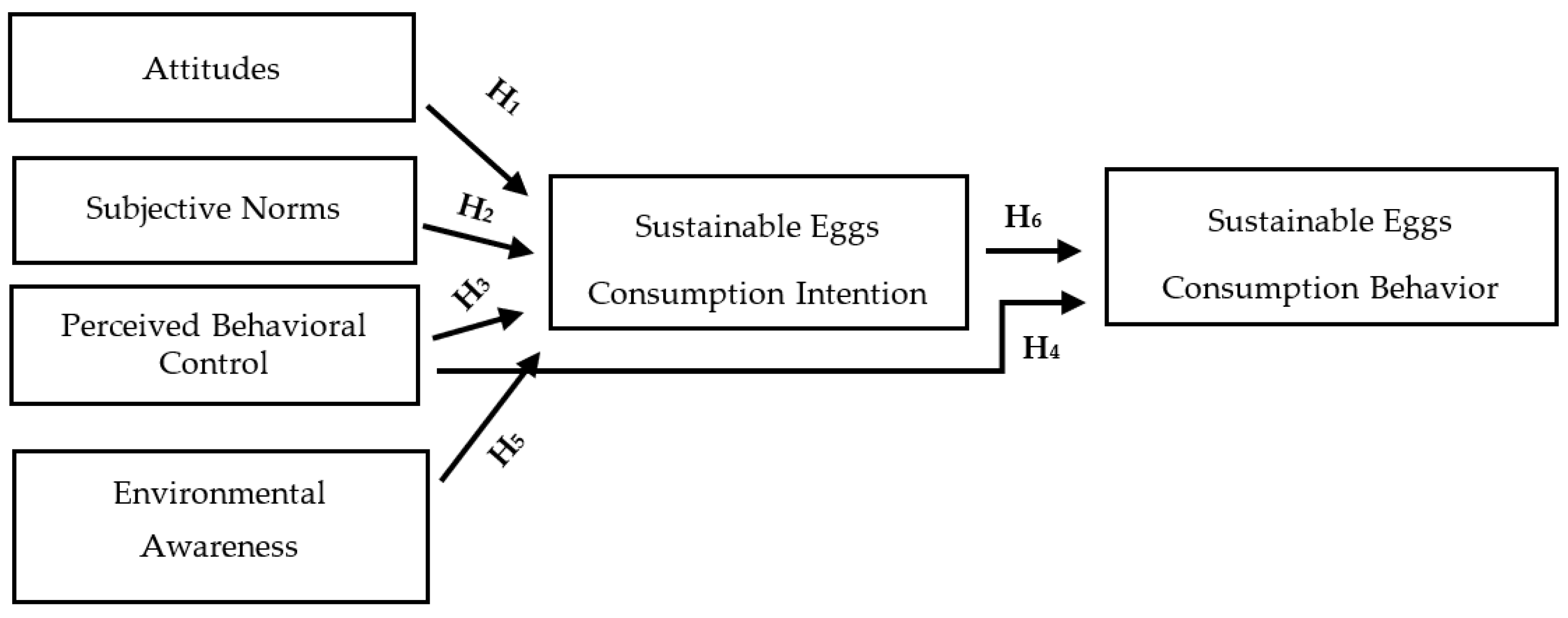

3. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

3.2. Research Hypotheses

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

4.1.1. Questionnaire Design

4.1.2. Measurement Scales

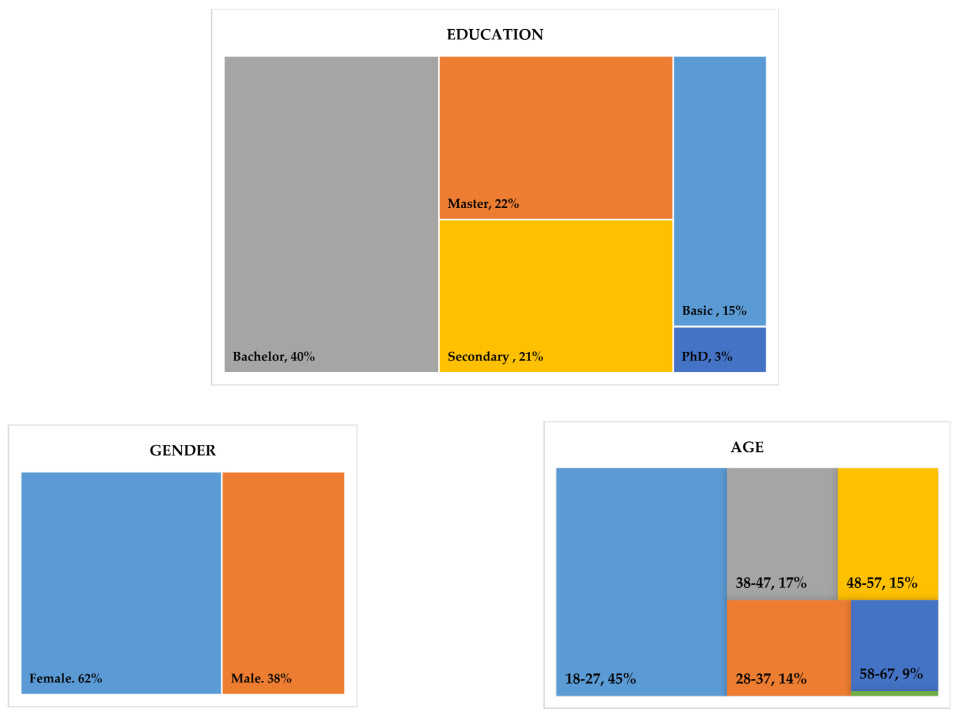

4.2. Sample Socioeconomic Description

4.3. Sample Egg Consumption and Purchase Description

5. Results

5.1. Reliability and Viability

5.2. Structure Model Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbu, A.; Catană, Ș.-A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.-I.; Ioanid, A. Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior toward Green Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Cricelli, L.; Mauriello, R.; Strazzullo, S. Consumer Perceptions of Sustainable Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Palit, D. Challenges in Natural Resource Management for Ecological Sustainability. In Natural Resources Conservation and Advances for Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavič, P. Evolution and Current Challenges of Sustainable Consumption and Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Domingo Nina, G.G.; Colgan, K.; Thakrar Sumil, K.; Tilman, D.; Lynch, J.; Azevedo Inês, L.; Hill Jason, D. Global Food System Emissions Could Preclude Achieving the 1.5° and 2 °C Climate Change Targets. Science 2020, 370, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, C.F.A.P.d.; Silva, C.d.S.T.P.d.; Silva, R.M.d.; Oliveira, M.J.d.S.; Neto, B.d.A.F. The Dietary Carbon Footprint of Portuguese Adults: Defining and Assessing Mitigation Scenarios for Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, V.; Valin, H.; Krisztin, T.; Havlík, P.; Herrero, M.; Kastner, T. The Role of Trade in the Greenhouse Gas Footprints of EU Diets. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 19, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Moreno Pires, S.; Iha, K.; Alves, A.A.; Lin, D.; Mancini, M.S.; Teles, F. Sustainable Food Transition in Portugal: Assessing the Footprint of Dietary Choices and Gaps in National and Local Food Policies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcão, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Rodrigues, S.; Lobato, L.; et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física, IAN-AF 2015–2016: Relatório de Resultados; University of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, E.; Sousa, S.; Viseu, C.; Larguinho, M.; Silva, J.; Alves, D. Analysing the Influence of Green Marketing Communication in Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breda, J.; Castro, L.S.N.; Whiting, S.; Williams, J.; Jewell, J.; Engesveen, K.; Wickramasinghe, K. Towards Better Nutrition in Europe: Evaluating Progress and Defining Future Directions. Food Policy 2020, 96, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, K.A.; Michelsen, M.K.; Carpenter, C.L. Modern Diets and the Health of Our Planet: An Investigation into the Environmental Impacts of Food Choices. Nutrients 2023, 15, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usturoi, M.G.; Rațu, R.N.; Crivei, I.C.; Veleșcu, I.D.; Usturoi, A.; Stoica, F.; Rusu, R.-M.R. Unlocking the Power of Eggs: Nutritional Insights, Bioactive Compounds, and the Advantages of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Enriched Varieties. Agriculture 2025, 15, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, S.; Szöllösi, L. Sustainability and Quality Aspects of Different Table Egg Production Systems: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Parvatiyar, A. Sustainable Marketing: Market-Driving, Not Market-Driven. J. Macromarketing 2021, 41, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabernard, L.; Pfister, S.; Oberschelp, C.; Hellweg, S. Growing Environmental Footprint of Plastics Driven by Coal Combustion. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjaitan, R.; Cahya, H.N. A Perspective of Theory of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior: Purchase Decision. J. Manajemen 2025, 29, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, L. Putting Farm Animal Welfare on the Table: Insights from Switzerland; University of Milan: Milan, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission on the European Citizens’ Initiative “End the Cage Age” (C(2021) 4747 Final); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://europa.eu/citizens-initiative/initiatives/details/2018/000004_en (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Majewski, E.; Potori, N.; Sulewski, P.; Wąs, A.; Mórawska, M.; Gębska, M.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Grontkowska, A.; Szili, V.; Erdős, A. End of the Cage Age? A Study on the Impacts of the Transition from Cages on the EU Laying Hen Sector. Agriculture 2024, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bussel, L.M.; Kuijsten, A.; Mars, M.; van ‘t Veer, P. Consumers’ Perceptions on Food-Related Sustainability: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Jiang, B. The Market Effectiveness of Regulatory Certification for Sustainable Food Supply: A Conjoint Analysis Approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euroconsumers. Portuguese Concerned About Farm Animal Welfare. The Portugal News. 2024. Available online: https://www.theportugalnews.com/news/2024-02-27/portuguese-concerned-about-farm-animal-welfare/86399 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Garcia, I. Innovations in Egg Production and Role in Sustainable Agriculture. Poult. Fish Wildl. Sci. 2024, 12, 270. Available online: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/innovations-in-egg-production-and-role-in-sustainable-agriculture.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Chantellier, V. International Trade in Animal Products and the Place of the European Union: Main Trends over the Last 20 Years. Animal 2021, 15, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zanten, H.H.E.; Simon, W.; van Selm, B.; Wacker, J.; Maindl, T.I.; Frehner, A.; Hijbeek, R.; van Ittersum, M.K.; Herrero, M. Circularity in Europe strengthens the sustainability of the global food system. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodenburg, T.B.; Giersberg, M.F.; Petersan, P.; Shields, S. Freeing the hens: Workshop outcomes for applying ethology to the development of cage-free housing systems in the commercial egg industry. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 251, 105629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, E.; Scappaticci, G.; Banterle, A.; Alamprese, C. What is the role of environmental sustainability knowledge in food choices? A case study on egg consumers in Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 141038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Lazzarini, G.; Funk, A.; Siegrist, M. Measuring consumers’ knowledge of the environmental impact of foods. Appetite 2021, 167, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, D.; Kallas, Z.; Pappa, M.; Gil, J.M. Are consumers’ egg preferences influenced by animal-welfare conditions and environmental impacts? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska-Solis, J.; Barska, A. Exploring the preferences of consumers’ organic products in aspects of sustainable consumption: The case of the Polish consumer. Agriculture 2021, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Olde, E.M.; van der Linden, A.; olde Bolhaar, L.D.; de Boer, I.J.M. Sustainability challenges and innovations in the Dutch egg sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerini, F.; Alfnes, F.; Schjøll, A. Organic- and animal welfare-labelled eggs: Competing for the same consumers? J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güney, O.I.; Giraldo, L. Consumers’ attitudes and willingness to pay for organic eggs: A discrete choice experiment study in Turkey. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, I.C.; Weeks, C.A.; Wilson, L.R.M.; Nicol, C.J. Consumer perceptions of free-range laying hen welfare. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1999–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, L.; Truninger, M.; Almli, V.L.; Ferreira, V.; Maia, R.L.; Teixeira, P. Self-reported practices by Portuguese consumers regarding eggs’ safety: An analysis based on critical consumer handling points. Food Control 2022, 133, 108635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Hübner, G.; Bogner, F.X. Contrasting the Theory of Planned Behavior with the Value-Belief-Norm model in explaining conservation behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 2150–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shan, B. Exploring the role of health consciousness and environmental awareness in purchase intentions for green-packaged organic foods: An extended TPB model. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1528016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior; Thomson South-Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2006; p. 774. ISBN 9780324271973. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, S.F.; Barbosa, B.; Cunha, H.; Oliveira, Z. Exploring the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchase Intention: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.C.; Makatouni, A. Consumer perception of organic food production and farm animal welfare. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazhan, M.; Shafiei Sabet, F.; Borumandnia, N. Factors affecting purchase intention of organic food products: Evidence from a developing nation context. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 3469–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacho, F. What influences consumers to purchase organic food in developing countries? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3695–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pacho, F.; Liu, J.; Kajungiro, R. Factors Influencing Organic Food Purchase Intention in Developing Countries and the Moderating Role of Knowledge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.F.; Gaber, H.R.; El Essawi, N. Examining the factors that affect consumers’ purchase intention of organic food products in a developing country. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.M.; Phan, T.H.; Nguyen, H.L.; Dang, T.K.T.; Nguyen, N.D. Antecedents of purchase intention toward organic food in an asian emerging market: A study of urban vietnamese consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, J.; Testa, F.; Rizzi, F. The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R. Altruistic or egoistic: Which value promotes organic food consumption among young consumers? A study in the context of a developing nation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, M.A.; Akbar, M.; Danish, M. Understanding the Antecedents of Organic Food Consumption in Pakistan: Moderating Role of Food Neophobia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Pereira, O. Antecedents of Consumers’ Intention and Behavior to Purchase Organic Food in the Portuguese Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Li, M.; Hao, Y. Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food among Chinese University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Shelat, S.; Gross, M.E.; Smallwood, J.; Seli, P.; Taxali, A.; Sripada, C.S.; Schooler, J.W. Opening the black box: Think Aloud as a method to study the spontaneous stream of consciousness. Conscious. Cogn. 2025, 128, 103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Simon, H.A. Verbal reports as data. Psychol. Rev. 1980, 87, 215–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.C.; Ericsson, K.A.; Best, R. Do procedures for verbal reporting of thinking have to be reactive? A meta-analysis and recommendations for best reporting methods. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 316–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanujaya, B.; Indra Prahmana, R.C.; Mumu, J. Likert scale in social sciences research: Problems and difficulties. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 17, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Zou, Z.; Cheng, C. A review of causal analysis methods in geographic research. Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 172, 105929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.M.; Morris, N.J.; Nock, N.L. Structural equation modeling. In Statistical Human Genetics: Methods and Protocols; Elston, R.C., Satagopan, J.M., Sun, S., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gana, K.; Broc, G. Structural Equation Modeling with Lavaan; ISTE/Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Rigdon, E.E.; Straub, D.W. Editor’s comments: An update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Raats, M.M.; Shepherd, R. Moral Concerns and Consumer Choice of Fresh and Processed Organic Foods. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 2088–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, T.; Cousins, A.L.; Neilson, L.; Price, M.; Hardman, C.A.; Wilkinson, L.L. Sustainable Food Consumption across Western and Non-Western Cultures: A Scoping Review Considering the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 114, 105086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer ‘’Attitude–Behavioral Intention’’ Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; Willemsen, L.M.; Van Der Aa, E.P. ‘’This Post Is Sponsored’’: Effects of Sponsorship Disclosure on Persuasion Knowledge and Electronic Word of Mouth in the Context of Facebook. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 38, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Country | Methodology | Main Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| De Marchi et al. [29] | Italy | Online survey 1013 respondents | Environmental knowledge influences the choice of sustainable eggs. Consumers value free-range farming, local production and the protection of biodiversity, but the latter is less recognized. |

| Hartmann et al. [30] | Switzerland | Online survey 612 respondents | Insufficient knowledge about the environmental impact of food makes it difficult to understand and make policies for sustainable consumption effective. |

| Rahmani et al. [31] | Spain | Discrete choice experiment 1045 respondents | Consumers are not willing to pay for organic eggs. Those who prefer free-range eggs are pro-environment, under 40 years old and earn more than EUR 1500 a month. |

| Wojciechowska-Solis & Barska [32] | Poland | Proprietary survey questionnaire 1067 respondents | There is a statistical link between the environmental awareness of consumers, which includes beneficial effects on health, nutritional content and the non-addition of substances in food production, and the tendency to buy organic products, such as eggs. |

| de Olde et al. [33] | Netherlands | Interviews & survey 24 stakeholders | The interest of consumers has focused predominantly on animal welfare and the efficient use of resources. |

| Gerini et al. [34] | Norway | Choice experiment 900 respondents | Consumers are more willing to pay for organic eggs when they buy organic food more often. However, a segment of consumers is not willing to buy organic eggs even if they cost the same as other eggs. |

| Güney & Giraldo [35] | Turkey | Choice experiment 552 respondents | Consumers have realized that organic eggs are healthy, nutritious, and delicious. In the consumer’s decision to buy organic eggs, individual benefits prevailed over collective benefits. |

| Pettersson et al. [36] | United Kingdom | Questionnaire 6378 respondents | Consumers perceive free-range eggs as having a better flavor and hens as being “happier” and “healthier”. Opinions differed on the factors that contribute to hen welfare, while they converged on the adequacy of resources. |

| Junqueira et al. [37] | Portugal | Online survey 933 respondents | Consumers are concerned about the quality and safety of eggs, price, origin, and production method. The criteria that have the least impact on the purchasing decision are the nutritional properties and the brand. |

| Latent Variable | Items |

|---|---|

| Attitudes (A) | A1: I believe that consuming eggs produced organically and by free-range hens is important for the preservation of the environment. |

| A2: I believe that the consumption of eggs produced organically and by free-range hens is important for animal welfare. | |

| A3: I think it is very important for consumers to value sustainability in their egg consumption decisions. | |

| A4: I believe that consuming organic eggs or eggs produced by free-range hens is more beneficial to human health. | |

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1: I believe that the choice to consume organic eggs or free-range chickens is appreciated by the people closest to me. |

| SN2: I believe that most of the people I live with support the consumption of organic eggs and those produced by free-range hens. | |

| SN3: The people who are important to me believe that I should consume organic eggs and eggs produced by free-range hens. | |

| Environmental Awareness and Concern (EAC) | EAC1: It is important that the food I eat is produced in such a way as to avoid contamination and pollution of soil, air and water. |

| EAC2: It is important that food production uses fewer resources and produces less waste. | |

| EAC3: Food production must be conducted without the use of harmful pesticides and synthetic chemical fertilizers. | |

| EAC4: It is important that the food I consume is produced by companies that promote environmental and social sustainability. | |

| EAC5: Today’s society seriously harms nature. | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | PBC1: I think it is easy for me to have access to eggs produced in a more sustainable way (organic or free-range hens). |

| PBC2: I have control over the decision to buy more sustainably produced eggs (organic or free-range hens). | |

| PBC3: I believe I have enough knowledge about the benefits of more sustainably produced eggs (organic or free-range hens). | |

| Consumer Intention (I) | I1: I plan to buy eggs soon from production methods that promote animal welfare. |

| I2: I intend to soon consume organic eggs or eggs from free-range hens. | |

| I3: I intend to consume eggs with wellness certification or organic seal. | |

| I4: It is my goal to consume eggs from hens fed with natural or organic feed. | |

| Consumer Behavior (CB) | CB1: I usually consume eggs from production methods that promote animal welfare. |

| CB2: I usually consume organic eggs or eggs from free-range hens. | |

| CB3: I usually consume eggs with animal welfare certification or an organic seal. | |

| CB4: I prefer to consume eggs from hens fed with natural or organic feed. |

| Construct | Item | Loading | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | A1 | 0.894 | 0.884 | 0.968 | 0.968 |

| A2 | 0.962 | ||||

| A3 | 0.952 | ||||

| A4 | 0.951 | ||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.922 | 0.834 | 0.938 | 0.938 |

| SN2 | 0.888 | ||||

| SN3 | 0.93 | ||||

| EAC | EAC1 | 0.928 | 0.757 | 0.939 | 0.937 |

| EAC2 | 0.955 | ||||

| EAC3 | 0.755 | ||||

| EAC4 | 0.85 | ||||

| EAC5 | 0.849 | ||||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.822 | 0.736 | 0.893 | 0.888 |

| PBC2 | 0.902 | ||||

| PBC3 | 0.848 | ||||

| I | I1 | 0.872 | 0.789 | 0.937 | 0.936 |

| I2 | 0.908 | ||||

| I3 | 0.936 | ||||

| I4 | 0.833 | ||||

| CB | CB1 | 0.902 | 0.712 | 0.908 | 0.906 |

| CB2 | 0.887 | ||||

| CB3 | 0.81 | ||||

| CB4 | 0.768 |

| A | SN | EAC | PBC | I | CB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.94 | |||||

| SN | 0.634 | 0.914 | ||||

| EAC | 0.858 | 0.564 | 0.87 | |||

| PBC | 0.68 | 0.853 | 0.58 | 0.858 | ||

| I | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.888 | |

| CB | 0.645 | 0.802 | 0.564 | 0.815 | 0.777 | 0.844 |

| Path | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | t-Statistics | ||

| H1: A → I | 0.485 | 0.127 | 0.455 | 3.81 | <0.001 |

| H2: SN → I | 0.376 | 0.127 | 0.443 | 2.955 | 0.003 |

| H3: PBC → I | −0.003 | 0.161 | −0.003 | −0.016 | 0.987 |

| H4: PBC → CB | 0.615 | 0.107 | 0.554 | 5.77 | <0.001 |

| H5: EAC → I | −0.032 | 0.114 | −0.029 | −0.281 | 0.779 |

| H6: I → CB | 0.446 | 0.109 | 0.406 | 4.081 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sousa, S.; Correia, E.; Sá, V.; Viseu, C.; Maduro, I.; Sousa, L. Egg Consumption Patterns and Sustainability: Insights from the Portuguese Context. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15141462

Sousa S, Correia E, Sá V, Viseu C, Maduro I, Sousa L. Egg Consumption Patterns and Sustainability: Insights from the Portuguese Context. Agriculture. 2025; 15(14):1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15141462

Chicago/Turabian StyleSousa, Sara, Elisabete Correia, Vera Sá, Clara Viseu, Inês Maduro, and Laércia Sousa. 2025. "Egg Consumption Patterns and Sustainability: Insights from the Portuguese Context" Agriculture 15, no. 14: 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15141462

APA StyleSousa, S., Correia, E., Sá, V., Viseu, C., Maduro, I., & Sousa, L. (2025). Egg Consumption Patterns and Sustainability: Insights from the Portuguese Context. Agriculture, 15(14), 1462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15141462